Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Lower Gi Bleed NG

Caricato da

bocah_britpopTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Lower Gi Bleed NG

Caricato da

bocah_britpopCopyright:

Formati disponibili

LOWER GI BLEEDNG

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

A 68 yrs old presents to the ER with BRBPR. He has several

episodes, beginning on the evening before presentation.

He describes the bleeding as profuse and filling the toilet, he felt

light headed and almost passed out while sitting on the toilet.

PMHx: htn

Meds: amlodipine

P.Ex: B.P. =86/42mm hg, pulse = 134/min,

pt. is orthostatic.

Abdominal examination reveals slight abdominal distention

with hyperactive bowel sounds.

Rectal exam shows gross blood

Wbc-10

Hct-28 %

Plt-180

Lytes wnl

Coagulation profile wnl

LFTs wnl

Estimation of blood loss

Estimated Fluid and Blood Losses in Shock

Class 1 Class 2 Class 3 Class 4

Blood Loss,

mL

Up to 750 750-1500 1500-2000 >2000

Blood Loss,%

blood volume

Up to 15% 15-30% 30-40% >40%

Pulse Rate,

bpm

<100 >100 >120 >140

Blood

Pressure

Normal Normal Decreased Decreased

Respiratory

Rate

Normal or

Increased

Decreased Decreased Decreased

Urine

Output,

mL/h

14-20 20-30 30-40 >35

CNS/Mental

Status

Slightly

anxious

Mildly

anxious

Anxious,

confused

Confused,

lethargic

Fluid

Replacement,

3-for-1 rule

Crystalloid Crystalloid

Crystalloid

and blood

Crystalloid

and blood

Initial steps in the management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Airway protection

Airway monitoring

Endotracheal intubation (if indicated)

Hemodynamic stabilization

Large bore intravenous access

Intravenous fluids

Red cell transfusion (for symptomatic anemia)

Fresh-frozen plasma, platelets (if indicated)

Consider erythropoeitin

Nasogastric oral administration

Large bore orogastric tube/lavage

Clinical and laboratory monitoring

Serial vital signs

Serial hemograms, coagulation profiles, and chemistries (as clinically indicated)

Electrocardiographic monitoring

Hemodynamic monitoring (if indicated in high-risk patients)

Endoscopic examination and therapy

RESUSCITATION

High-risk patients (eg, those who are elderly or who have severe co

morbid illnesses such as coronary disease or cirrhosis) should

receive packed red blood cell transfusions to maintain the

hematocrit above 30 percent.

Patients who are elderly or have known cardiovascular disease are

at increased risk for a myocardial infarction and should thus be

monitored appropriately; consideration should be given to ruling

out a myocardial infarction.

Young and otherwise healthy patients should be transfused to

maintain their hematocrit above 20 percent.

Patients with active bleeding and a coagulopathy (prolonged

prothrombin time with INR >1.5) or low platelet count

(<50,000/microL) should also be transfused with fresh frozen

plasma and platelets, respectively.

Lower GI bleeding

Next step

Risk stratification

Initial Emergency Department Risk Stratification for Patients with Gastrointestinal

Bleeding

Low Risk Moderate Risk High Risk

Age <60 Age >60

Initial SBP 100 mm

Hg

Initial SBP <100 mm

Hg

Persistent SBP <100 mm Hg

Normal vitals for 1 hr Mild ongoing

tachycardia for 1 hr

Persistent moderate/severe

tachycardia

No transfusion

requirement

Transfusions required

4 U

Transfusion required >4 U

No active major

comorbid diseases

Stable major comorbid

diseases

Unstable major comorbid diseases

No liver disease Mild liver diseasePT

normal or near-normal

Decompensated liver diseasei.e.,

coagulopathy, ascites,

encephalopathy

No moderate-risk or

high-risk clinical

features

No high-risk clinical

features

Risk stratification

Strate and colleagues retrospectively collected data on 24

clinical variables available in the first 4 hours of

evaluation in 252 consecutive patients.

Seven independent predictors of severity in acute

LGIB

hypotension

tachycardia,

syncope,

nontender abdominal exam,

bleeding within 4 hours of presentation,

aspirin use, and

more than two comorbid diseases

Risk stratification

Based on these factors, patients could be

stratified into three risk groups:

Patients with more than three risk factors

had an 84% risk of severe bleeding,

One to three risk factors a 43% risk, and

No risk factors a 9% risk.

In another study clinical predictors in the

first hour of evaluation in patients with

severe LGIB included

initial hematocrit of no more than 35%,

presence of abnormal vital signs 1 hour

after initial medical evaluation, and

gross blood on initial rectal examination.

Next step

localization

An upper gastrointestinal source of bleeding is detected in 10% to

15% of patients presenting with severe hematochezia .

Patients with hemodynamic compromise and hematochezia should

have a nasogastric tube placed.

I f bile is present, an upper source is unlikely.

I f the aspirate is nondiagnostic (no blood or bile), or if there is

a strong suspicion of an upper bleeding source (i.e., history of

previous peptic ulcer disease or frequent NSAID use), then an

upper endoscopy should be performed before examining the colon

.

An upper endoscopy should be performed if no source of bleeding is

identified during colonoscopy.

LOCALIZATION

The duration, frequency, and color of blood passed per rectum

may help discern the severity and location of bleeding.

Characteristically, melena or black, tarry stool, indicates bleeding

from an upper gastrointestinal or small bowel source,

Maroon color suggests rt. Sided lesion

whereas bright red blood per rectum signifies bleeding from the

left colon or rectum. However, patient and physician reports of

stool color are often inaccurate and inconsistent

In addition, even with objectively defined bright red bleeding,

significant proximal lesions can be found on colonoscopy

LOCALIZATION

past medical history may also help to elucidate a specific bleeding source.

antecedent constipation or diarrhea (hemorrhoids, colitis),

the presence of diverticulosis (diverticular bleeding),

receipt of radiation therapy (radiation enteritis),

recent polypectomy (postpolypectomy bleeding), and

vascular disease/hypotension (ischemic colitis).

A family history of colon cancer increases the likelihood of a colorectal

neoplasm and generally calls for a complete colonic examination in

patients with hematochezia.

Nonetheless, even after a detailed history, physicians cannot reliably

predict which patients with hematochezia will have significant pathology

and a history of bleeding from one source does not eliminate the

possibility of bleeding from a different source.

LOCALIZATION

Multiple factors make the identification of a precise

bleeding source in LGIB challenging.

The diversity of potential sources,

The length of bowel involved,

The need for colon cleansing, and

The intermittent nature of bleeding.

In up to 40% of patients with LGIB, more than one

potential bleeding source will be noted and

Stigmata of recent bleeding in LGIB are infrequently

identified

As a result, no definitive source will be found in a large

percentage of patients

Clinical scenarios

Pt. continued to bleed with hypotension

and tachycardia. Patient requires 2 units

of PRBCs

Pt. stopped bleeding. Vitals normalizes

Options to diagnose and control

the bleeding

RBC scan, requires 0.5-1 ml/min bleeding

Mesenteric angiography, requires 1-1.5

ml/min bleeding

Colonoscopy

Surgery

Meckels scan

Scenario one-

Pt. continues to bleed

and is unstable.

Rbc scan vs colonoscopy

COLONOSCOPY

Colonoscopy is undoubtedly the best test for confirming the source

of LGIB and for excluding ominous diagnoses, such as

malignancy.

The diagnostic yield of colonoscopy ranges from 45% to 95%

Perform after golytely prep(w/in 12-24h)

Identifies lesion in 75 % or more

Can provide endoscopic therapy

Early colonoscopy associated with reduced stay

Complications 0.5-1 %

most patients undergoing radiographic evaluation for LGIB

regardless of findings and interventions will subsequently require

a colonoscopy to establish the cause of bleeding.

URGENT COLONOSCOPY

Jensen et al

Reduced rate of rebleeding and emergency surgery

from diverticular bleed when compared to historical

controls

Green et al

100 randomized to urgent (w/in 8hrs) colonoscopy

to standard care

Definitive source more common in urgent group

No difference in multiple clinical outcomes

Issue is still not resolved

CLINICAL SCENARIO

Patient continues to bleed

RBC scan is positive on the left side?

How much true this information is??

What to do next? surgery, ?angio with

embolization?

RADIONUCLIDE SCAN

radionuclide scanning has variable accuracy, cannot confirm the

source of bleeding, and may delay other diagnostic and therapeutic

procedures.

Correct localization rate is 41-100%

Accuracy appears to be best when the scan becomes positive within a

short period of time

In one study, 42% of patients underwent an incorrect surgical

procedure based on scintigraphy results. In addition, several studies

have found that regardless of accuracy, scintigraphy did not affect

surgical management

Predictors of positive response

-hemodynamic instability= 62% vs. 21%

->2units transfused within 24 hrs= 64% vs. 32%

CLINICAL SCENARIO

Patient underwent angiogram with

embolization

Vitals improved

What are the chances that pt. will

rebleed?

Colonoscopy?

MESENTERIC ANGIOGRAM

Selective embolization initially controls

hemorrhage in up to 100% of patients, but

rebleeding rates are 15% to 40%

Advantages:

-Precise localization

-Can provide therapy with intra-arterial

vasopressin or coil embolization

-Procedure of choice in briskly bleeding pts

-Minor complication rate of 9% and a 0%

major complication rate

Disadvantages:

-Invasive

-Less sensitive in detecting venous

bleeding

-Can cause ischemia, contrast

reactions, arterial injury

Advantages and disadvantages of common diagnostic procedures used in the evaluation of lower

gastrointestinal bleeding

Procedure Advantages Disadvantages

Colonoscopy Therapeutic possibilities Bowel preparation required

Diagnostic for all sources of

bleeding

Can be difficult to orchestrate without on-

call endoscopy facilities or staff

Needed to confirm diagnosis in

most patients regardless of initial

testing

Invasive

Efficient/cost-effective

Angiography No bowel preparation needed Requires active bleeding at the time of the

exam

Therapeutic possibilities Less sensitive to venous bleeding

May be superior for patients with

severe bleeding

Diagnosis must be confirmed with

endoscopy/surgery

Serious complications are possible

Radionuclide

scintigraphy

Noninvasive Variable accuracy (false positives)

Sensitive to low rates of bleeding Not therapeutic

No bowel preparation May delay therapeutic intervention

Easily repeated if bleeding recurs Diagnosis must be confirmed with

endoscopy/surgery

Flexible

sigmoidoscopy

Diagnostic and therapeutic Visualizes only the left colon

Minimal bowel preparation Colonoscopy or other test usually

necessary to rule out right-sided lesions

Easy to perform

Pt. under went colonoscopy for definitive

diagnosis.

In how many patients there will be more

than one potential diagnosis?

In how many patients there will be no

diagnosis found?

ETIOLOGY

Differential Diagnosis of Lower Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage

COLONIC BLEEDING (95%) % SMALL BOWEL BLEEDING (5%)

Diverticular disease 30-40 Angiodysplasias

Ischemia 5-10 Erosions or ulcers (potassium, NSAIDs)

Anorectal disease 5-15 Crohn's disease

Neoplasia 5-10 Radiation

Infectious colitis 3-8 Meckel's diverticulum

Postpolypectomy 3-7 Neoplasia

Inflammatory bowel disease 3-4 Aortoenteric fistula

Angiodysplasia 3

Radiation colitis/proctitis 1-3

Other 1-5

Unknown 10-25

DIAGNOSTIC DIFFICULTIES

When compared with EGD for upper GI bleeding, the diagnostic

modalities for lower GI bleeding are not as sensitive or specific in making

an accurate diagnosis.

Diagnostic evaluation is further complicated by the observation that, in up

to 40% of patients with lower GI bleeding, more than one potential source

of hemorrhage is identified.

If more than one source is identified, it is critical to confirm the

responsible lesion before initiating aggressive therapy.

This approach may occasionally require a period of observation with

several episodes of bleeding before a definitive diagnosis can be made.

In fact, in up to 25% of patients with lower GI hemorrhage, the bleeding

source is never accurately identified.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

COLONOSCOPY SHOWED

old and BRB in mid colon

tics seen throughout

Dx= probably diverticular beed

Pt was d/c home

CLINICAL SCENARIO

2 wks later readmitted with rebleed and

syncope

Hct 32--- 24

Urgent tagged RBC scan neg

Deep mid AC diverticulum with clot that

could not be removed

What is the next step

SURGERY

Surgery usually is employed for hemorrhage in two settings:

massive or recurrent bleeding.

It is required in 15% to 25% of patients who have diverticular

bleeding and is recommended for patients with a high transfusion

requirement (generally more than four units within a 24-hour

period or greater than 10 units total)

Recurrent bleeding from diverticula occurs in 20% to 40% of

patients and generally is considered an indication for surgery

In patients with serious comorbid medical conditions and without

exsanguinating hemorrhage, this decision should be made

carefully.

Great effort should be made to accurately localize the site of

bleeding preoperatively so that segmental rather than subtotal

colectomy can be performed Operative mortality is 10% even with

accurate localization and up to 57% with blind subtotal colectomy.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- 09 - Monitoring and Complications of Parenteral NutritionDocumento14 pagine09 - Monitoring and Complications of Parenteral Nutritionbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- 03 - Nutritional Screening and Assessment PDFDocumento8 pagine03 - Nutritional Screening and Assessment PDFbocah_britpop100% (1)

- 17 - Enhanced Recovery PrinciplesDocumento7 pagine17 - Enhanced Recovery Principlesbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- 17 - Enhanced Recovery PrinciplesDocumento7 pagine17 - Enhanced Recovery Principlesbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- Materi PerioperatifDocumento11 pagineMateri PerioperatifSyahdat NurkholiqNessuna valutazione finora

- 17 - The Traumatized PatientDocumento7 pagine17 - The Traumatized Patientbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- 03 - Energy BalanceDocumento8 pagine03 - Energy Balancebocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- 09 - Compounding and Ready-To-use Preparation of PN Pharmaceutical Aspects. Compatibility and Stability Consideration DrugDocumento21 pagine09 - Compounding and Ready-To-use Preparation of PN Pharmaceutical Aspects. Compatibility and Stability Consideration Drugbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- 08 - Oral and Sip FeedingDocumento11 pagine08 - Oral and Sip Feedingbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- Interaction of Bone and Vascular Disease in CKDDocumento7 pagineInteraction of Bone and Vascular Disease in CKDbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- 08 - Oral and Sip FeedingDocumento11 pagine08 - Oral and Sip Feedingbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- Indications, Contraindications and Monitoring of Enteral NutritionDocumento13 pagineIndications, Contraindications and Monitoring of Enteral Nutritionbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- 17 - Enhanced Recovery PrinciplesDocumento7 pagine17 - Enhanced Recovery Principlesbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- 17 - The Traumatized PatientDocumento7 pagine17 - The Traumatized Patientbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- 08 - Complications and Monitoring of enDocumento7 pagine08 - Complications and Monitoring of enbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- Weekly ChartDocumento7 pagineWeekly Chartbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- m84 PDFDocumento14 paginem84 PDFMico Ga Bisa GendutNessuna valutazione finora

- 08 - Techniques of Enteral NutritionDocumento16 pagine08 - Techniques of Enteral Nutritionbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

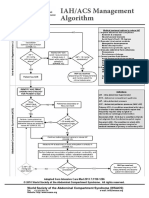

- IAH/ACS Management Algorithm Adapted from Intensive Care MedDocumento1 paginaIAH/ACS Management Algorithm Adapted from Intensive Care Medbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- 09 - Compounding and Ready-To-use Preparation of PN Pharmaceutical Aspects. Compatibility and Stability Consideration DrugDocumento21 pagine09 - Compounding and Ready-To-use Preparation of PN Pharmaceutical Aspects. Compatibility and Stability Consideration Drugbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- Materi PerioperatifDocumento11 pagineMateri PerioperatifSyahdat NurkholiqNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Disc RadioDocumento29 pagineCase Disc Radiobocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- Intraabdominal Pressure MonitoringDocumento10 pagineIntraabdominal Pressure Monitoringbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- Presentation 1Documento2 paginePresentation 1bocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- ACS SabistonDocumento10 pagineACS Sabistonbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- Interaction of Bone and Vascular Disease in CKDDocumento7 pagineInteraction of Bone and Vascular Disease in CKDbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- IAH ACS Medical Management 2014Documento1 paginaIAH ACS Medical Management 2014bocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- University of Colorado NICHE Practice Survey SummaryDocumento48 pagineUniversity of Colorado NICHE Practice Survey Summarybocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- Upper Abdominal Pain Case ReportDocumento2 pagineUpper Abdominal Pain Case Reportbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- HydrocephalusDocumento51 pagineHydrocephalusbocah_britpopNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- HPS STGDocumento33 pagineHPS STGDJGGNessuna valutazione finora

- Billroth ii procedure explainedDocumento2 pagineBillroth ii procedure explainedJasmin MirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- 4 2 - 181 182 PDFDocumento2 pagine4 2 - 181 182 PDFNam LeNessuna valutazione finora

- MCN Test DrillsDocumento20 pagineMCN Test DrillsFamily PlanningNessuna valutazione finora

- QuestionsDocumento26 pagineQuestionsLyka Mae Imbat - PacnisNessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Gynaecology: Juta - Co.za/pdf/23698Documento3 pagineClinical Gynaecology: Juta - Co.za/pdf/23698Thato MotaungNessuna valutazione finora

- 42 - Circulation and Gas ExchangeDocumento97 pagine42 - Circulation and Gas ExchangeTrisha SantillanNessuna valutazione finora

- Dysphagia Lusoria: A Comprehensive ReviewDocumento6 pagineDysphagia Lusoria: A Comprehensive ReviewDante ChavezNessuna valutazione finora

- Abdominal wall anatomy and common abdominal incisionsDocumento42 pagineAbdominal wall anatomy and common abdominal incisionsSamar AhmadNessuna valutazione finora

- Children's dental health: Retention of teethDocumento4 pagineChildren's dental health: Retention of teethKandiwapaNessuna valutazione finora

- Easy Pharyngeal Anesthesia with Lidocaine LozengesDocumento6 pagineEasy Pharyngeal Anesthesia with Lidocaine LozengespaulaNessuna valutazione finora

- AUTHORIZED HOSPITALS LIST CPRI GOI CGHSDocumento11 pagineAUTHORIZED HOSPITALS LIST CPRI GOI CGHSNaveenkumar PalanisamyNessuna valutazione finora

- Right Flank AbomasopexyDocumento24 pagineRight Flank Abomasopexy7candlesburningNessuna valutazione finora

- Unicompartmental Knee ArthroplastyDocumento10 pagineUnicompartmental Knee Arthroplastycronoss21Nessuna valutazione finora

- Balloon PumpDocumento1 paginaBalloon PumpRaghavendra PrasadNessuna valutazione finora

- Imaging Evaluation of Tracheobronchial InjuriesDocumento14 pagineImaging Evaluation of Tracheobronchial InjuriesSantiago TapiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Colleen J. Rutherford - Differentiating Surgical Instruments (With CDROM) - F. A. Davis Company (First Published March 7th 2005) (2011)Documento211 pagineColleen J. Rutherford - Differentiating Surgical Instruments (With CDROM) - F. A. Davis Company (First Published March 7th 2005) (2011)Amra Fejzic100% (1)

- L1) Oral Cavity, Palate and TongueDocumento39 pagineL1) Oral Cavity, Palate and Tongue3amroooni.a.aNessuna valutazione finora

- Bio Data Name: Prof. Dr. Vinod Kapoor Date/ Place of Birth Educational QualificationsDocumento6 pagineBio Data Name: Prof. Dr. Vinod Kapoor Date/ Place of Birth Educational Qualificationsayub_008Nessuna valutazione finora

- F3 C3 Human Blood Circulatory System ExerciseDocumento3 pagineF3 C3 Human Blood Circulatory System ExerciseCharvini SreeNessuna valutazione finora

- Newborn Capillary Blood CollectionDocumento3 pagineNewborn Capillary Blood CollectionYwagar YwagarNessuna valutazione finora

- Cog Thread LiftDocumento5 pagineCog Thread Liftemilly vidya71% (7)

- Carotid and Vertebral Ultrasonography - Dr. DanielDocumento74 pagineCarotid and Vertebral Ultrasonography - Dr. DanielSuci Rahayu Evasha100% (1)

- GH-ZOLL-Autopulse Quick Case-Instruction ManualDocumento80 pagineGH-ZOLL-Autopulse Quick Case-Instruction ManualjillNessuna valutazione finora

- Medetomidine-Buprenorphine Combo Reduces Isoflurane Needs in CatsDocumento9 pagineMedetomidine-Buprenorphine Combo Reduces Isoflurane Needs in CatsDaniela MartínezNessuna valutazione finora

- Medical Emergency ProcedureDocumento2 pagineMedical Emergency ProcedureAmeena HarisNessuna valutazione finora

- PEMASANGAN ECG 3 LEAD DAN 5 LEADDocumento3 paginePEMASANGAN ECG 3 LEAD DAN 5 LEADPrio Si IyoNessuna valutazione finora

- WelcomeDocumento74 pagineWelcomeSagarRathodNessuna valutazione finora

- Complete IssueDocumento212 pagineComplete IssueAmril MukminNessuna valutazione finora

- V-Gel Cleaning & User GuideDocumento3 pagineV-Gel Cleaning & User GuideInstrulife OostkampNessuna valutazione finora