Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

The Effectiveness of Psychotherapy With Refugees and Asylum by Walter Renner

Caricato da

Silvia IlariCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The Effectiveness of Psychotherapy With Refugees and Asylum by Walter Renner

Caricato da

Silvia IlariCopyright:

Formati disponibili

J Immigrant Minority Health (2009) 11:4145 DOI 10.

1007/s10903-007-9095-1

ORIGINAL PAPER

The Effectiveness of Psychotherapy with Refugees and Asylum Seekers: Preliminary Results from an Austrian Study

Walter Renner

Published online: 19 October 2007 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2007

Abstract An Austrian Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) offered psychotherapy to 37 asylum seekers and refugees (21 of them female) with a mean age of 36.1 years (s = 7.5), with the majority of them from Chechnya or Afghanistan. Comparative data between the start of therapy and the time of evaluation revealed a highly signicant positive effect (d = 0.77), while most therapies were still going on. By a retrospective measure of perceived change, 85% of the participants reported signicant improvements. The results show that even under difcult conditions, when working with asylum seekers and refugees, psychotherapy can be effective. Keywords Asylum Refugee Psychotherapy Evaluation

In Austria, in 2006, over 13,000 people have sought political asylum with applicants from Chechnya and Afghanistan being the most prominent groups among them [1]. Renner et al. [2, 3] have shown in accordance with previous literature [4, 5], that approximately 50% of asylum seekers show symptoms of traumatization and therefore are in need of psychotherapeutic help. An alternative approach, employed for example by the metaPart of this article was translated from an internal annual report for 2006 on the work of ASPIS. In this report also the data published in the present article were used. W. Renner (&) Social Psychology, Ethnopsychoanalysis and Psychotraumatology Unit, Department of Psychology, Alps-Adria-University of Klagenfurt, Universitatsstrasse 65-67, 9020 Klagenfurt, Austria e-mail: walter.renner@uni-klu.ac.at

analysis of Porter and Haslam [6], emphasized that psychopathological symptoms among refugees should not only be interpreted as consequences of traumatic events encountered in the past, but also reect difculties of acculturation in their host countries. In their meta-analysis of 59 studies, Porter and Haslam [6] found a mean effect size of 0.41 on various measures of mental health, differentiating groups of refugees, asylum seekers and otherwise displaced persons from control groups, indicating the migrants poorer mental health status. ASPIS (the Turkish word for turtle, indicating protection by its shell), a center of research and counseling for victims of violence at the University of Klagenfurt (Austria) is afliated to the Department of Psychology. This Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) is nanced by the European Refugee Fund (ERF) and, to a smaller extent, by the provincial government of Carinthia. It offers psychotherapy free of charge to asylum seekers and refugees, who are frequently suffering either from psychological trauma after encountering imprisonment, torture, mutilation, or rape in their home countries, or who seek relief from problems associated with their and their families unsettled situation in Austria. In the light of the high number of asylum seekers and refugees in Austria, the work of ASPIS can by no means sufce to help those who are in need on a large scale, but, together with various ERF-nanced institutions in other Austrian provinces, ASPIS can function as kind of a pilot project, towards an evidence based psychotherapeutic work with refugees and asylum seekers. The present psychotherapy evaluation study intends to give a preliminary account of this work, to summarize the efforts of ASPIS, and to evaluate critically the outcome of this work. The hypothesis underlying this study is that even under precarious circumstances, and with chronically impaired clients, psychotherapy can work effectively.

123

42

J Immigrant Minority Health (2009) 11:4145

Method Participants Prospective clients usually were informed about the possibility of undergoing psychotherapy at ASPIS by word of mouth, by their social workers or medical doctors. In a rst meeting, an ASPIS psychotherapist assessed the clients with respect to their suitability for psychotherapy. Only clients with a history of severe traumatization and with marked post-traumatic symptoms were accepted for psychotherapy. In cases of extremely severe psychopathology, however, clients were assigned to initial psychiatric treatment before recommending psychotherapy. As most clients belonged to Islamic culture, usually women were assigned to female therapists and men to male ones. In addition, in many cases the nature of traumatic events suggested a same-gender therapeutic relationship. With respect to therapeutic method, clients were assigned at random. As will be explained below in more detail, comparative and retrospective data were collected. In 2006, comparative data were obtained from 37 clients, 16 men and 21 women with a mean age of 36.1 years (s = 7.5, range 22 53 years). For this purpose, data on clinical symptoms from 2006 were compared with those obtained at the start of therapy. In 13 cases the latest questionnaire stemmed from Spring, in 24 cases it stemmed from Fall 2006. Additional Retrospective data were only obtained from clients who had been in psychotherapy for a minimum of 3 months. Thus, only 33 of a total of 37 clients, 15 men and 18 women with a mean age of 35.4 years (s = 7.3, range 2248 years) provided such data. In 12 cases the latest questionnaire on retrospective data stemmed from Spring, and in 21 cases it stemmed from Fall 2006. Of the total of 37 clients, 18 came from Chechnya, 7 from Afghanistan, 4 from Kosovo, 2 from Armenia, 2 from Georgia, and 1 from Bosnia, Iran, Iraq, and Poland, respectively. The mean duration of therapies was 18.0 months (SD = 14.0, Median = 12, Range 654 months).

might happen by confronting clients with traumatic memories too early or in inappropriate way. All therapies were conducted with the aid of interpreters. All the ASPIS therapists are highly qualied according to strict Austrian psychotherapy legislation. ASPIS therapy is offered to the clients free of charge.

Evaluation Methods With respect to the psychometric instruments employed, Renner et al. [2] have conrmed previous ndings, for example by Marsella et al. [7] that cultural issues have to be considered in order to achieve reliable and valid results. Most importantly, we corroborated results by Mezzich et al. [8] and many others implying that the DSM-IV (4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual) Diagnostic Criteria of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) are specic for Western society and should not be applied to clients from non-Western cultures. Moreover, our clinical experience has shown in accordance with results for example by Ehlers [9], that post-traumatic symptomatology is frequently accompanied by additional symptoms of anxiety and depression. In addition, Porter and Haslams [6] abovementioned arguments kept us from limiting the scope of this evaluation study to post-traumatic symptoms in the narrow sense of PTSD. On the contrary, it seemed advisable to address in the course of this study a wide range of clinical symptoms as well as an individuals perceived ability to function normally in his or her everyday environment. In order to obtain comparative data, the clients of ASPIS were asked to ll in a symptom questionnaire, which will be described below at the very beginning of therapy and afterwards every six months, in Spring and Fall of each year. Taking into account that therapies frequently were interrupted for some period of time and were continued later, in the present study, the symptom level assessed in 2006 will be compared with the symptom level at the start of therapy, regardless of the question, whether therapy was completed in 2006 or whether it is still going on. In addition, we obtained retrospective data by a questionnaire sensitive to perceived change of experience and behavior, which will also be described below. All the clients were informed about the nature of the questionnaires submitted to them. They gave oral informed consent to complete the questionnaires for evaluation purposes.

Psychotherapeutic Methods Twenty-seven participants underwent psychodramatic treatment (17 of them in a single and 10 in a group setting; total of three different therapists, two females and one male), six of them behavior therapy (one female and one male therapist) and four of them existential analysis (one male therapist) in a single setting. Regardless of their therapeutic schools, ASPIS therapists in the course of their interventions consistently promote clients resources and are extremely careful to avoid re-traumatization which

Questionnaires (1) Comparative data were obtained by a questionnaire of clinically relevant symptoms, the German version of

123

J Immigrant Minority Health (2009) 11:4145

43

(2)

the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI, [10]). This 53 items questionnaire is the short version of the German Symptom Checklist 90 Revised (SCL-90-R, [11]). All the BSI-items have to be rated on ve-point scales with respect to their intensity during the past 7 days. The BSI measures clinical symptoms on nine dimensions, namely (1) Somatization, (2) Obsessive Compulsive, (3) Interpersonal Sensitivity, (4) Depression, (5) Anxiety, (6) Hostility, (7) Phobic Anxiety, (8) Paranoid Ideation, and (9) Psychoticism. In addition, the BSI, as well as the SCL-90-R offers three global indices of symptomatology, most importantly the Global Severity Index (GSI), which is the arithmetic mean of the perceived intensity of all 53 symptoms on the ve-point scale. Huttenbrenner [12] has found that the BSI was highly reliable when used with refugees and asylum seekers with the aid of interpreters, but she could not replicate the nine clinical scales in factor analysis. Thus, for the purpose of the present study, only the global Index GSI was used. As a retrospective measure of therapeutic progress, we used the German Questionnaire of Change in Expe rience and Behavior (Veranderungsfragebogen des Erlebens und Verhaltens, VEV, Zielke and KopfMehnert [3] in its revised version VEV-2000-R, Zielke and Kopf-Mehnert [14]) which comprises 42 items referring to alterations like feeling more or less depressed, showing more or less self-assertive behavior when dealing with others, nding more or less meaning in life, etc. For each item, on a seven-point scale respondents are asked to indicate whether they feel that, as compared to the time before therapy had started, the respective change occurred only slightly, or to a moderate or marked degree. Finally, a neutral category is provided, which the client should mark if he or she could detect no change at all. Thus, from the 42 items, a maximal index of change of 294 can be obtained.

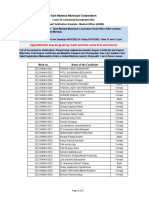

The amount of change achieved by the total group can be seen from the box plot in Fig. 1. The degree of improvement reached by each individual client is shown in Fig. 2.

Questionnaire of Change in Experience and Behavior The 33 clients who responded to the Questionnaire of Change in Experience and Behavior (Veranderungsfragebogen des Erlebens und Verhaltens, VEV) achieved a mean index of change of 218.3 (s = 33.9, range = 116285). From Table 1 the total number of cases can be seen which showed improvement or deterioration on the various levels of signicance or remained unchanged in the course of therapy. According to this table, 28 out of 33 clients or 85% had reported a signicant improvement on the VEV. The difference between the rst and the second measurement on the symptom level by BSI correlates highly signicantly with the Index of Change as obtained by the VEV (r = .476, p \ 0.005).

Discussion On the basis of comparative data obtained by the BSI, for the total number of clients examined, a highly signicant improvement with an effect size of d = +0.77 was found. According to Shalev et al. [15], behavior therapy with

3,00

All the questionnaires were submitted during therapy sessions with the help of interpreters.

2,00

Results Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) Since their therapies had started, the 37 participants achieved a reduction of their symptoms which was highly signicant when the whole group was considered (t = 4.329, df = 36, P = 0.000). At the start of therapy, the mean GSI was 2.06 (s = 0.68), while at the time of evaluation in 2006, the mean GSI was 1.47 (s = 0.85). The corresponding effect size was d = 0.77 (CL95% = 0.381.15).

1,00

0,00 GSI at start of therapy GSI at time of evaluation 2006

Fig. 1 Amount of symptom change achieved by 37 clients in the course of therapy: Boxplot (GSI = Global Severity Index, i.e., the arithmetic mean of all responses)

123

44

J Immigrant Minority Health (2009) 11:4145

4,00

3,00

2,00

1,00

0,00 0,00 1,00 2,00 3,00 4,00

GSI at Start of Therapy

Fig. 2 Amount of symptom change achieved by 37 clients in the course of therapy: Scatterplot (GSI = Global Severity Index, i.e., the arithmetic mean of all responses) Table 1 Number of signicantly improved, unchanged and signi cantly deteriorated cases in VEV (Veranderungsfragebogen des Erlebens und VerhaltensQuestionnaire of change in experience and behavior) Change Improvement P 0.001 Improvement P 0.05 No signicant change Deterioration P 0.05 Deterioration P 0.001 Total VEV Index of change 200 187 150 and 187 \150 \137 Frequency 26 2 3 1 1 33 Percent 78.8 6.1 9.1 3.0 3.0 100.0

studies the percentage of responders and non-responders should be analyzed making use of the concepts of Reliable Change and Clinical Signicance [16, 17]. In addition, larger sample sizes would allow us to examine the effectiveness of various therapeutic approaches. There are considerable limitations that must be dealt with when evaluating psychotherapy with refugees and asylum seekers: First of all, most of the clients have underwent serious stressful events, including imprisonment, interrogations and torture, and therefore are reluctant to answer any further questions, to ll in questionnaires, and so on. Therefore, the use of psychometric instruments must be kept to a minimum, in order to reduce the danger of re-traumatization and in order to secure the participants continued co-operation. Asylum seekers are, by their nature, an extremely unstable population. As a consequence, therapies frequently are interrupted or discontinued for reasons which can be inuenced neither by the client nor by the therapist, making it impossible to achieve proper pre-, post- and follow-up measurements as they are common practice in psychotherapy evaluation. For similar reasons, control groups can hardly be established. To complicate matters further, therapeutic work with refugees and asylum seekers must make use of interpreters. Even if they work efciently, therapeutic relationship lacks immediateness and emotionally laden subtleties are difcult to communicate. It is also important to note that Western therapeutic techniques hardly account for culturally specic symptomatology [2, 3] and therapists frequently are unaware of culture specicities relevant to their clients. In spite of these difculties and limitations, the present preliminary results indicate that psychotherapy as conducted by ASPIS clearly is benecial and helps clients to cope with severe traumatization as well as chronic strain resulting from multiple problems of acculturation in their host country.

Acknowledegment I am indebted to Karl Peltzer and Klaus Ottomeyer for valuable comments and suggestions pertaining to this research.

traumatized clients usually yields effect sizes between +1.00 and +2.00, but it must be considered that, in the present case, therapies are not yet completed. In the light of this fact, the effect size found in this study clearly indicates the effectiveness of ASPIS therapies. In accordance with the results of the BSI, the ndings obtained by the VEV conrmed quite clearly that ASPIS psychotherapy is effective. Differential GSI values as found by the BSI, were correlated moderately and signicantly with the VEV Index of Change, thus indicating that both methods measure different aspects of therapeutic change. Moreover, group means yield a distorted view of reality, as with any therapeutic approach and for a variety of reasons, among the clients, responders and non-responders will be found. Thus, on the basis of larger samples in future

GSI at Time of Evaluation 2006

References

1. Ministry of the Interior. Asylstatistik 2006 [Asylum statistics]. 2007. http://www.bmi.gv.at/downloadarea/asyl_fremdenwesen_ statistik/AsylJahr2006.pdf. Retrieved June 15, 2007. 2. Renner W, Salem I, Ottomeyer K. Cross-cultural validation of psychometric measures of trauma in groups of asylum seekers from Chechnya, Afghanistan and West Africa. Soc Behav Personal 2006;35(5):110114. 3. Renner W, Salem I, Ottomeyer K. Posttraumatic stress in asylum seekers from Chechnya, Afghanistan and West Africa Differential ndings obtained by quantitative and qualitative methods in three Austrian samples. In: Wilson JP, Tang C, editors. The

123

J Immigrant Minority Health (2009) 11:4145 cross-cultural assessment of psychological trauma and PTSD. New York: Springer; 2007. p. 23978. Buljan D, Vrcek D, Cekic-Arambasin A, Karlovic D, Zoricic Z, Golik-Gruber V. Posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol dependence, and somatic disorders in displaced persons. Alcoholism 2002;38(12):3540. Turner SW, Bowie C, Dunn G, Shapo L, Yule W. Mental health of Kosovan Albanian refugees in the UK. Brit J Psychiatr 2003;182:4448. Porter M, Haslam N. Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons. J Am Med Assoc 2005;294:60212. Marsella AJ, Dubanoski J, Hamada WC, Morse H. The measurement of personality across cultures. Historical, conceptual, and methodological issues and considerations. Am Behav Sci 2000;44:4162. Mezzich JE, Kleinman A, Fabrega H, Parron DL. editors. Culture and psychiatric diagnosis: a DSM-IV perspective. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1996. Ehlers A. Posttraumatische Belastungsstorung [Post-traumatic stress disorder]. Gottingen: Hogrefe; 1999. Franke GH. Brief symptom inventory von L. R. Derogatis (Kurz form der SCL-90-R) Deutsche Version. Gottingen: Beltz; 2000. Franke GH. SCL-90-R. Die Symptom-Checkliste von Derogatis Deutsche Version. Gottingen: Beltz; 1995.

45 12. Huttenbrenner E. Diagnostische Verfahren zur Identizierung eines psychologischen Traumas bei Asylwerbern und Asylwerb erinnen unter Berucksichtigung des kulturellen Aspekts [Diagnostic methods for the assessment of psychological trauma in asylum seekers with special consideration of cultural aspects]. Diploma thesis, University of Klagenfurt; 2004. 13. Zielke M, Kopf-Mehnert C. Veranderungsfragebogen des Erlebens und Verhaltens [Questionnaire of change in experience and behavior]. Gottingen: Beltz; 1978. 14. Zielke M, Kopf-Mehnert C. Der VEV-R-2001: Entwicklung und testtheoretische Reanalyse der revidierten Form des Ver anderungsfragebogens des Erlebens und Verhaltens (VEV) [Development, test theory and re-analysis of the revised form of the questionnaire of change in experience and behavior]. Praxis Klinische Verhaltensmedizin und Rehabilitation 2001;53:719. 15. Shalev AY, Friedman MJ, Foa EB, Keane TM. Integration and summary. In: Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, editors. Effective treatments for PTSD. Practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. New York: Guilford; 2000. 16. Jacobson NS, Follette WC, Revenstorf D. Toward a standard denition of clinically signicant change. Behav Ther 1984;15:30911. 17. Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical signicance: a statistical approach to dening meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991;59:129.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9. 10. 11.

123

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Science: Airs - LMDocumento30 pagineScience: Airs - LMJoey Orencia Rimando100% (2)

- Nba FormatDocumento31 pagineNba FormatchetanNessuna valutazione finora

- Appointments May Be Given by Merit and First Come First Serve BasisDocumento5 pagineAppointments May Be Given by Merit and First Come First Serve BasisRohit DubeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Using Computers in SchoolDocumento7 pagineAdvantages and Disadvantages of Using Computers in SchoolAlina Cobiloiu50% (2)

- Selling The Wheel SummaryDocumento10 pagineSelling The Wheel Summaryprincy.kumar8568Nessuna valutazione finora

- Microfinance as a Poverty Alleviation ToolDocumento6 pagineMicrofinance as a Poverty Alleviation ToolMeenazNessuna valutazione finora

- Candor Info Solution Private Limited customer application formDocumento8 pagineCandor Info Solution Private Limited customer application formPrabal KajlaNessuna valutazione finora

- TERM PAPER of TaxationDocumento25 pagineTERM PAPER of TaxationBobasa S AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- ERAN Capacity Monitoring GuideDocumento37 pagineERAN Capacity Monitoring GuidehekriNessuna valutazione finora

- Braket H4Documento32 pagineBraket H4leonor maria zamora montes100% (1)

- ECO1001 Economics For Decision Making 2021 Session 2 EXAMDocumento7 pagineECO1001 Economics For Decision Making 2021 Session 2 EXAMIzack FullerNessuna valutazione finora

- Koresponden Penulis: XX: Implementasi Nilai-Nilai Etika, Moral Dan Akhlak Dalam Perilaku BelajarDocumento10 pagineKoresponden Penulis: XX: Implementasi Nilai-Nilai Etika, Moral Dan Akhlak Dalam Perilaku Belajaryusria1982Nessuna valutazione finora

- ConcreteDocumento1 paginaConcreteRyan_RajmoolieNessuna valutazione finora

- Cangurul Lingvist - Faza II - 2017 - IDEEDocumento2 pagineCangurul Lingvist - Faza II - 2017 - IDEEhaldanmihaelaNessuna valutazione finora

- Shia ChatDocumento19 pagineShia Chatmirabadi1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Nguyen Thi Ngoc Anh: ContactDocumento1 paginaNguyen Thi Ngoc Anh: Contactánh nguyễnNessuna valutazione finora

- Indra A Case Study in Comparative MythologyDocumento41 pagineIndra A Case Study in Comparative MythologybudimahNessuna valutazione finora

- Daily Crime Journal Police Station: Taguig CityDocumento3 pagineDaily Crime Journal Police Station: Taguig CityVINCENessuna valutazione finora

- Approach To STDS2Documento56 pagineApproach To STDS2Daniel ThomasNessuna valutazione finora

- Conceptual Framework - LG Qualitative PDFDocumento48 pagineConceptual Framework - LG Qualitative PDFKarl AndresNessuna valutazione finora

- Drama TermsDocumento17 pagineDrama TermsRasool Bux SaandNessuna valutazione finora

- Plant Two-Component Signaling Systems in ArabidopsisDocumento20 paginePlant Two-Component Signaling Systems in ArabidopsisMonika AnswalNessuna valutazione finora

- Exalted 3e - Three BehemothsDocumento8 pagineExalted 3e - Three BehemothsCannibal_OrcNessuna valutazione finora

- Dreamland Vs JohnsonDocumento13 pagineDreamland Vs JohnsonheymissrubyNessuna valutazione finora

- PS-bill of Exchange ActDocumento35 paginePS-bill of Exchange ActPhani Kiran MangipudiNessuna valutazione finora

- Council of Chalcedon and its ConsequencesDocumento11 pagineCouncil of Chalcedon and its Consequencesapophatism100% (1)

- Course Package in PATH-FIT II DANCE 2nd Semester AY 2021-2022Documento52 pagineCourse Package in PATH-FIT II DANCE 2nd Semester AY 2021-2022John Ian NisnisanNessuna valutazione finora

- Konica 7155Documento2 pagineKonica 7155isyo411Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ed 319 Lesson Plan 1 DiversityDocumento12 pagineEd 319 Lesson Plan 1 Diversityapi-340488115Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sample Cover Letter For Job in GermanyDocumento20 pagineSample Cover Letter For Job in GermanyShejoy T.JNessuna valutazione finora