Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Nine Deadly Sins

Caricato da

gshiva1123Descrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Nine Deadly Sins

Caricato da

gshiva1123Copyright:

Formati disponibili

from the editor

Editor in Chief: Steve McConnell

I

Construx Software

software@construx.com

The Nine Deadly Sins of Project Planning

Steve McConnell

t a time when some software organizations have achieved close to perfect on-time delivery records,1 others continue to suffer mediocre results. Surveys generally indicate that poor project planning is one of the top sources of problems. How can you recognize a badly planned software project? Here are nine of the deadliest sins Ive found in project planning.

1. Not planning at all

By far the most common planning problem is simply not planning at all, and this sin is easily avoided. A person need not be an expert planner to plan effectively. Ive seen numerous instances of projects planned by rank amateurs that have run well simply because the people in charge had carefully considered their projects specific needs. Forced to choose between an expert project planner who doesnt carefully think through his plan or an amateur who has thoroughly evaluated his project needs, Ill bet on the amateur every time.

create setup programs, convert data from previous versions, perform cutover to new systems, perform compatibility testing, and other pesky kinds of work that take up more time than we would like to admit. Some late projects propose to catch up by reducing their originally planned testing cycle; they reason that there probably wont be very many defects to detect or correct. (I leave as an exercise for the reader to determine whyif this is really the casethey didnt plan for a shorter testing cycle in the first place.)

3. Failure to plan for risk

In Design Paradigms,2 Henry Petroski argues that the most spectacular failures in bridge design were generally preceded by periods of success that led to complacency in the creation of new designs. Designers of failed bridges were lulled into copying the attributes of successful bridges and didnt pay enough attention to each new bridges potential failure modes. For software projects, actively avoiding failure is as important as emulating success. In many business contexts, the word risk isnt mentioned unless a project is already in deep trouble. In software, a project planner who isnt using the word risk every day and incorporating risk management into his plans probably isnt doing his job. As Tom Gilb says, If you do not actively attack the risks on your project, they will actively attack you.3

2. Failing to account for all project activities

If Deadly Sin #1 is not planning at all, Deadly Sin #2 is not planning enough. Some project plans are created using the assumption that no one on the software team will get sick, attend training, go on vacation, or quit. Core activities are often underestimated to a great degree. Plans created using unrealistic assumptions like these set up a project for disaster. There are numerous variations on this theme. Some projects neglect to account for ancillary activities such as the effort needed to

Copyright 2001 Steven C. McConnell. All Rights Reserved.

4. Using the same plan for every project

Some organizations grow familiar with a particular approach to running software projects, which is known as the way we do things around here. When an organization uses this approach, it tends to do well as long as the new projects look like the old projects. When new

September/ October 2001

IEEE SOFTWARE

FROM THE EDITOR

D E PA R T M E N T E D I T O R S

Bookshelf: Warren Keuffel, wkeuffel@computer.org Country Report: Deependra Moitra, Lucent Technologies d.moitra@computer.org Design: Martin Fowler, ThoughtWorks, fowler@acm.org Loyal Opposition: Robert Glass, Computing Trends, rglass@indiana.edu Manager: Don Reifer, Reifer Consultants, dreifer@sprintmail.com Quality Time: Jeffrey Voas, Cigital, voas@cigital.com

STAFF

projects look different, however, reusing old plans can cause more harm than good. Good plans address specific conditions of the project for which they are created. Many elements can be reused, but project planners should think carefully about the extent to which each element of a previous plan still applies to the new project context.

embrace prepackaged methodologies whole-hog are sometimes reluctant to change them midstream when theyre not working. They think the problem is with their application of the plan when, in fact, the problem is with the plan. Good project planning should occur and recur incrementally throughout a project.

5. Applying prepackaged plans indiscriminately

A close cousin to Deadly Sin #3 is reusing a generic plan someone else created without applying your own critical thinking or considering your projects unique needs. Someone elses plan usually arrives in the form of a book or methodology that a project planner applies out of the box. Current examples include the Rational Unified Process,4 Extreme Programming,5 and to some extent (despite my best intentions to the contrary) my own Software Project Survival Guide6 and my companys CxOne. These prepackaged plans can help avoid Deadly Sins #1 and #2, but they are not a substitute for thinking about and optimizing your plans to the unique demands of your project. No outside expert can possibly understand a projects specific needs as well as the people directly involved. Project planners should always tailor the experts plan to their specific circumstances. Fortunately, Ive found that project planners who are aware enough of planning issues to read software engineering books usually also have enough common sense to be selective about the parts of the prepackaged plans that are likely to work for them.

7. Planning in too much detail too soon

Some well-intentioned project planners try to map out a whole projects worth of activities early on. But a software project consists of a constantly unfolding set of decisions, and each project phase creates dependencies for future decisions. Since planners do not have crystal balls, attempting to plan distant activities in too much detail is an exercise in bureaucracy that is almost as bad as not planning at all. The more work that goes into creating prematurely detailed plans, the higher the likelihood the plan will become shelfware (Deadly Sin #6). No one likes to throw away previous work, and project planners sometimes try to force-fit the projects reality into their earlier plans rather than laboriously revising their prematurely detailed plans. I think of good project planning like driving at night with my cars headlights on. I might have a road map that tells me how to get from City A to City B, but the distance I can see in detail in my headlights is limited. On a mediumsize or large project, macro-level project plans should be mapped out endto-end early in the project. Detailed, micro-level planning should generally be conducted only a few weeks at a time and just in time.

Senior Lead Editor Dale C. Strok dstrok@computer.org Group Managing Editor Crystal Chweh Associate Editors Jenny Ferrero and Dennis Taylor Staff Editors Shani Murray, Scott L. Andresen, and Kathy Clark-Fisher Magazine Assistants Dawn Craig software@computer.org Pauline Hosillos Art Director Toni Van Buskirk Cover Illustration Dirk Hagner Technical Illustrator Alex Torres Production Artists Carmen Flores-Garvey and Larry Bauer Acting Executive Director Anne Marie Kelly Publisher Angela Burgess Assistant Publisher Dick Price Membership/Circulation Marketing Manager Georgann Carter Advertising Assistant Debbie Sims

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

6. Allowing a plan to diverge from project reality

One common approach to planning is to create a plan early in the project, then put it on the shelf and let it gather dust for the remainder of the project. As project conditions change, the plan becomes increasingly irrelevant, so by mid-project the project runs free-form, with no real relationship between the unchanging plan and project reality. This Deadly Sin is exacerbated by Deadly Sin #5project planners who

Greg Goth, Keri Schreiner, and Gil Shif

8. Planning to catch up later

For projects that get behind schedule, one common mistake is planning to make up lost time later. The typical rationalization is that, The team was climbing a learning curve early in the project. We learned a lot of lessons the hard way. But now we understand what were doing and should be able to finish the project quickly. Wrong answer! A 1991 survey of more than 300

Editorial: All submissions are subject to editing for clarity, style, and space. Unless otherwise stated, bylined articles and departments, as well as product and service descriptions, reflect the authors or firms opinion. Inclusion in IEEE Software does not necessarily constitute endorsement by the IEEE or the IEEE Computer Society. To Submit: Send 2 electronic versions (1 word-processed and 1 postscript or PDF) of articles to Magazine Assistant, IEEE Software, 10662 Los Vaqueros Circle, PO Box 3014, Los Alamitos, CA 90720-1314; software@computer.org. Articles must be original and not exceed 5,400 words including figures and tables, which count for 200 words each.

IEEE SOFTWARE

September/ October 2001

FROM THE EDITOR

projects found that projects hardly ever make up lost timethey tend to get further behind.7 The flaw in the rationalization is that software teams make their highest-leverage decisions earliest in the projectthe time during which new technology, new business areas, and new methodologies are the least well understood. As the team works its way into the later phases of the project, it wont speed up; it will slow down as it encounters the consequences of mistakes it made earlier and invests time correcting those mistakes.

mortem review.8 A postmortem review might not erase the sins of projects past, but it can certainly help prevent sins on future projects.

EDITOR IN CHIEF: Steve McConnell 10662 Los Vaqueros Circle Los Alamitos, CA 90720-1314 software@construx.com EDITOR IN CHIEF EMERITUS: Alan M. Davis, Omni-Vista

A S S O C I AT E E D I T O R S I N C H I E F

References

1. S. Ahuja, Laying the Groundwork for Success, IEEE Software, vol. 16, no. 6, Nov. Dec. 1999, pp. 7275. 2. H. Petroski, Design Paradigms, Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, U.K., 1994. 3. T. Gilb, Principles of Software Engineering Management, Addison-Wesley, Reading, Mass., 1988. 4. P. Kruchten, The Rational Unified Process: An Introduction, 2nd ed., Addison-Wesley, Reading, Mass., 2000. 5. K. Beck, Extreme Programming: Embrace Change, Addison-Wesley, Reading, Mass., 2000. 6. S. McConnell, Software Project Survival Guide, Microsoft Press, Redmond, Wash., 1997. 7. M. van Genuchten, Why Is Software Late? An Empirical Study of Reasons for Delay in Software Development, IEEE Trans. Software Eng., vol. 17, no. 6, June 1991, pp. 582590. 8. B. Collier, T. Demarco, and P. Fearey, A Defined Process for Project Postmortem Review, IEEE Software, vol. 13, no. 4, JulyAug. 1996, pp. 6572.

Design: Maarten Boasson, Quaerendo Invenietis boasson@quaerendo.com Construction: Terry Bollinger, Mitre Corp. terry@mitre.org Requirements: Christof Ebert, Alcatel Telecom christof.ebert@alcatel.be Management: Ann Miller, University of Missouri, Rolla millera@ece.umr.edu Quality: Jeffrey Voas, Cigital voas@cigital.com Experience Reports: Wolfgang Strigel, Software Productivity Center; strigel@spc.ca

EDITORIAL BOARD

9. Not learning from past planning sins

The deadliest sin of all might be not learning from earlier deadly sins. Software projects can take a long time, and peoples memories can be clouded by ego and the passage of time. By the end of a long project, it can be difficult to remember all the early decisions that affected the projects conclusion. One easy way to counter these tendencies and prevent future deadly sins is to conduct a structured project post-

Don Bagert, Texas Tech University Richard Fairley, Oregon Graduate Institute Martin Fowler, ThoughtWorks Robert Glass, Computing Trends Natalia Juristo, Universidad Politcnica de Madrid Warren Keuffel, independent consultant Brian Lawrence, Coyote Valley Software Karen Mackey, Cisco Systems Deependra Moitra, Lucent Technologies, India Don Reifer, Reifer Consultants Suzanne Robertson, Altantic Systems Guild Wolfgang Strigel, Software Productivity Center Karl Wiegers, Process Impact

INDUSTRY ADVISORY BOARD

Upcoming

Topics

November/December 01: Extreme Programming from a CMM Perspective January/February 02: Building Systems Securely from the Ground Up March/April 02: Building Internet Software May/June 02: Knowledge Management in Software Engineering

Robert Cochran, Catalyst Software (chair) Annie Kuntzmann-Combelles, Q-Labs Enrique Draier, PSINet Eric Horvitz, Microsoft Research David Hsiao, Cisco Systems Takaya Ishida, Mitsubishi Electric Corp. Dehua Ju, ASTI Shanghai Donna Kasperson, Science Applications International Pavle Knaflic, Hermes SoftLab Gnter Koch, Austrian Research Centers Wojtek Kozaczynski, Rational Software Corp. Tomoo Matsubara, Matsubara Consulting Masao Matsumoto, Univ. of Tsukuba Dorothy McKinney, Lockheed Martin Space Systems Nancy Mead, Software Engineering Institute Stephen Mellor, Project Technology Susan Mickel, AgileTV Dave Moore, Vulcan Northwest Melissa Murphy, Sandia National Laboratories Kiyoh Nakamura, Fujitsu Grant Rule, Software Measurement Services Girish Seshagiri, Advanced Information Services Chandra Shekaran, Microsoft Martyn Thomas, Praxis Rob Thomsett, The Thomsett Company John Vu, The Boeing Company Simon Wright, Integrated Chipware Tsuneo Yamaura, Hitachi Software Engineering

M A G A Z I N E O P E R AT I O N S C O M M I T T E E

Sorel Reisman (chair), James H. Aylor, Jean Bacon, Thomas J. Bergin, Wushow Chou, William I. Grosky, Steve McConnell, Ken Sakamura, Nigel Shadbolt, Munindar P. Singh, Francis Sullivan, James J. Thomas, Yervant Zorian

P U B L I C AT I O N S B O A R D

Rangachar Kasturi (chair), Angela Burgess (publisher), Jake Aggarwal, Laxmi Bhuyan, Mark Christensen, Lori Clarke, Mike T. Liu, Sorel Reisman, Gabriella Sannitti di Baja, Sallie Sheppard, Mike Williams, Zhiwei Xu

September/ October 2001

IEEE SOFTWARE

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Release Note GXP16xx 1.0.7.6Documento69 pagineRelease Note GXP16xx 1.0.7.6gshiva1123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Parallel Agile – faster delivery, fewer defects, lower costDa EverandParallel Agile – faster delivery, fewer defects, lower costNessuna valutazione finora

- 7 Insights Everyone Should Know About Chakras and How To Balance ThemDocumento13 pagine7 Insights Everyone Should Know About Chakras and How To Balance Themgshiva1123Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Complex Project Toolkit: Using design thinking to transform the delivery of your hardest projectsDa EverandThe Complex Project Toolkit: Using design thinking to transform the delivery of your hardest projectsValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Trust PresentationDocumento12 pagineTrust Presentationgshiva1123Nessuna valutazione finora

- An Architectural Brief For A Proposed 100 Bedded HospitalDocumento111 pagineAn Architectural Brief For A Proposed 100 Bedded Hospitalgshiva1123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Key Facts - TIA-942Documento8 pagineKey Facts - TIA-942gshiva1123Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Agile Codex: Re-inventing Agile Through the Science of Invention and AssemblyDa EverandThe Agile Codex: Re-inventing Agile Through the Science of Invention and AssemblyNessuna valutazione finora

- Zgouras Catherine Team Together 1 Teachers BookDocumento257 pagineZgouras Catherine Team Together 1 Teachers Booknata86% (7)

- Coding Fun Learn C Programming with Games, Animations, and Mobile AppsDa EverandCoding Fun Learn C Programming with Games, Animations, and Mobile AppsNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning Plans in The Context of The 21 ST CenturyDocumento29 pagineLearning Plans in The Context of The 21 ST CenturyHaidee F. PatalinghugNessuna valutazione finora

- The Complete Software Project Manager: Mastering Technology from Planning to Launch and BeyondDa EverandThe Complete Software Project Manager: Mastering Technology from Planning to Launch and BeyondValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (2)

- EXPERIMENT 1 - Bendo Marjorie P.Documento5 pagineEXPERIMENT 1 - Bendo Marjorie P.Bendo Marjorie P.100% (1)

- DevOps Handbook: What is DevOps, Why You Need it and How to Transform Your Business with DevOps PracticesDa EverandDevOps Handbook: What is DevOps, Why You Need it and How to Transform Your Business with DevOps PracticesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (3)

- Comparative Study On Analysis of Plain and RC Beam Using AbaqusDocumento9 pagineComparative Study On Analysis of Plain and RC Beam Using Abaqussaifal hameedNessuna valutazione finora

- Chomsky's Universal GrammarDocumento4 pagineChomsky's Universal GrammarFina Felisa L. AlcudiaNessuna valutazione finora

- CHASE SSE-EHD 1900-RLS LockedDocumento2 pagineCHASE SSE-EHD 1900-RLS LockedMarcos RochaNessuna valutazione finora

- Updated WorksheetDocumento5 pagineUpdated WorksheetJohn Ramer Lazarte InocencioNessuna valutazione finora

- I. Objectives Ii. Content Iii. Learning ResourcesDocumento13 pagineI. Objectives Ii. Content Iii. Learning ResourcesZenia CapalacNessuna valutazione finora

- Mediator Analysis of Job Embeddedness - Relationship Between Work-Life Balance Practices and Turnover IntentionsDocumento15 pagineMediator Analysis of Job Embeddedness - Relationship Between Work-Life Balance Practices and Turnover IntentionsWitty MindsNessuna valutazione finora

- Professional Test Driven Development with C#: Developing Real World Applications with TDDDa EverandProfessional Test Driven Development with C#: Developing Real World Applications with TDDNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Project Presentation of Jobairul Karim ArmanDocumento17 pagineResearch Project Presentation of Jobairul Karim ArmanJobairul Karim ArmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Does Prototyping Help or Hinder Good Requirements? What Are the Best Practices for Using This Method?Da EverandDoes Prototyping Help or Hinder Good Requirements? What Are the Best Practices for Using This Method?Nessuna valutazione finora

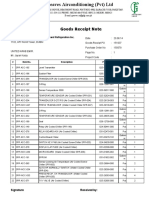

- Goods Receipt Note: Johnson Controls Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Inc. (YORK) DateDocumento4 pagineGoods Receipt Note: Johnson Controls Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Inc. (YORK) DateSaad PathanNessuna valutazione finora

- Operation and Service 69UG15: Diesel Generator SetDocumento72 pagineOperation and Service 69UG15: Diesel Generator Setluis aguileraNessuna valutazione finora

- Domain Driven Design : How to Easily Implement Domain Driven Design - A Quick & Simple GuideDa EverandDomain Driven Design : How to Easily Implement Domain Driven Design - A Quick & Simple GuideValutazione: 2.5 su 5 stelle2.5/5 (3)

- OB Case Study Care by Volvo UK 2020Documento1 paginaOB Case Study Care by Volvo UK 2020Anima AgarwalNessuna valutazione finora

- Monetizing Machine Learning: Quickly Turn Python ML Ideas into Web Applications on the Serverless CloudDa EverandMonetizing Machine Learning: Quickly Turn Python ML Ideas into Web Applications on the Serverless CloudNessuna valutazione finora

- ISO-50001-JK-WhiteDocumento24 pagineISO-50001-JK-WhiteAgustinusDwiSusantoNessuna valutazione finora

- Concept of Lokmitra Kendra in Himachal PradeshDocumento2 pagineConcept of Lokmitra Kendra in Himachal PradeshSureshSharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1.2 The Basic Features of Employee's Welfare Measures Are As FollowsDocumento51 pagine1.2 The Basic Features of Employee's Welfare Measures Are As FollowsUddipta Bharali100% (1)

- Information Technology Project Management Interview Questions: IT Project Management and Project Management Interview Questions, Answers, and ExplanationsDa EverandInformation Technology Project Management Interview Questions: IT Project Management and Project Management Interview Questions, Answers, and ExplanationsValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (4)

- Bombas KMPDocumento42 pagineBombas KMPReagrinca Ventas80% (5)

- Project Management Nation: Tools, Techniques, and Goals for the New and Practicing IT Project ManagerDa EverandProject Management Nation: Tools, Techniques, and Goals for the New and Practicing IT Project ManagerValutazione: 1 su 5 stelle1/5 (1)

- A Presentation On-: E-Paper TechnologyDocumento19 pagineA Presentation On-: E-Paper TechnologyRevanth Kumar TalluruNessuna valutazione finora

- Lafayette College Engineers Without Borders Project Leader HandbookDa EverandLafayette College Engineers Without Borders Project Leader HandbookNessuna valutazione finora

- DTS 600 GDO Installation ManualDocumento12 pagineDTS 600 GDO Installation Manualpiesang007Nessuna valutazione finora

- Scrum: What You Need to Know About This Agile Methodology for Project ManagementDa EverandScrum: What You Need to Know About This Agile Methodology for Project ManagementValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (32)

- Hexoloy SP Sic TdsDocumento4 pagineHexoloy SP Sic TdsAnonymous r3MoX2ZMTNessuna valutazione finora

- CKRE Lab (CHC 304) Manual - 16 May 22Documento66 pagineCKRE Lab (CHC 304) Manual - 16 May 22Varun pandeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Modern Front-end Architecture: Optimize Your Front-end Development with Components, Storybook, and Mise en Place PhilosophyDa EverandModern Front-end Architecture: Optimize Your Front-end Development with Components, Storybook, and Mise en Place PhilosophyNessuna valutazione finora

- Mobility StrategyDocumento38 pagineMobility StrategySoubhagya PNessuna valutazione finora

- ToiletsDocumento9 pagineToiletsAnonymous ncBe0B9bNessuna valutazione finora

- Software Project Estimation: Intelligent Forecasting, Project Control, and Client Relationship ManagementDa EverandSoftware Project Estimation: Intelligent Forecasting, Project Control, and Client Relationship ManagementNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 3Documento5 pagineUnit 3Narasimman DonNessuna valutazione finora

- ERP Solution in Hospital: Yangyang Shao TTU 2013Documento25 pagineERP Solution in Hospital: Yangyang Shao TTU 2013Vishakh SubbayyanNessuna valutazione finora

- Basics of Programming: A Comprehensive Guide for Beginners: Essential Coputer Skills, #1Da EverandBasics of Programming: A Comprehensive Guide for Beginners: Essential Coputer Skills, #1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hume 100 ReviewerDocumento7 pagineHume 100 ReviewerShai GaviñoNessuna valutazione finora

- Credit Card Authorization Form WoffordDocumento1 paginaCredit Card Authorization Form WoffordRaúl Enmanuel Capellan PeñaNessuna valutazione finora

- Project Management For Beginners: The ultimate beginners guide to fast & effective project management!Da EverandProject Management For Beginners: The ultimate beginners guide to fast & effective project management!Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- Solutions of Inverse Geodetic Problem in Navigational Applications PDFDocumento5 pagineSolutions of Inverse Geodetic Problem in Navigational Applications PDFLacci123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Number CardsDocumento21 pagineNumber CardsCachipún Lab CreativoNessuna valutazione finora

- Project Management: An Essential Guide for Beginners Who Want to Understand Agile, Scrum, Lean Six Sigma, Kanban and Kaizen When Applied to Managing ProjectsDa EverandProject Management: An Essential Guide for Beginners Who Want to Understand Agile, Scrum, Lean Six Sigma, Kanban and Kaizen When Applied to Managing ProjectsValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- Per Dev Dlp-1-2 - 3 SelfDocumento6 paginePer Dev Dlp-1-2 - 3 SelfMonisa SocorinNessuna valutazione finora

- Docs for Developers: An Engineer’s Field Guide to Technical WritingDa EverandDocs for Developers: An Engineer’s Field Guide to Technical WritingNessuna valutazione finora

- 9 Habits of Project Leaders: Experience- and Data-Driven Practical Advice in Project ExecutionDa Everand9 Habits of Project Leaders: Experience- and Data-Driven Practical Advice in Project ExecutionValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- The Triple Constraints in Project ManagementDa EverandThe Triple Constraints in Project ManagementNessuna valutazione finora

- Untrapped Value:: Software Reuse Powering Future ProsperityDa EverandUntrapped Value:: Software Reuse Powering Future ProsperityNessuna valutazione finora

- Software Engineering for Absolute Beginners: Your Guide to Creating Software ProductsDa EverandSoftware Engineering for Absolute Beginners: Your Guide to Creating Software ProductsNessuna valutazione finora

- How to Become a Software Engineer – A Beginners GuideDa EverandHow to Become a Software Engineer – A Beginners GuideNessuna valutazione finora

- AGILE PROJECT MANAGEMENT: Navigating Complexity with Efficiency and Adaptability (2023 Guide for Beginners)Da EverandAGILE PROJECT MANAGEMENT: Navigating Complexity with Efficiency and Adaptability (2023 Guide for Beginners)Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Quick and Dirty Hands-On Project Management GuideDa EverandThe Quick and Dirty Hands-On Project Management GuideNessuna valutazione finora

- How to Be a Successful Software Project ManagerDa EverandHow to Be a Successful Software Project ManagerNessuna valutazione finora

- Microsoft Project 2010 – Fast Learning HandbookDa EverandMicrosoft Project 2010 – Fast Learning HandbookValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (2)

- Learn to Program with Kotlin: From the Basics to Projects with Text and Image ProcessingDa EverandLearn to Program with Kotlin: From the Basics to Projects with Text and Image ProcessingNessuna valutazione finora