Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

More Trouble Than I Can Stand Thinking About Balancing Risk, Safety AndCost in Regulating Nuclear Energy

Caricato da

EnformableDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

More Trouble Than I Can Stand Thinking About Balancing Risk, Safety AndCost in Regulating Nuclear Energy

Caricato da

EnformableCopyright:

Formati disponibili

More Trouble Than I Can Stand Thinking About: Balancing Risk, Safety and Cost in Regulating Nuclear Energy

Peter A. Bradford1

One of the most dangerous phrases that nuclear officials can utter is That accident cant happen in my country. After the Three Mile Island accident in the U.S., Soviet officials came to the site and held a press conference at which they pointed out that the Three Mile Island design was not used in the Soviet Union, so no similar accident would occur in their country. Of course, they were right. Instead, seven years later, they had Chernobyl. After Chernobyl, many countries including Japan made solemn statements pointing out that their countries did not use the Soviet RMBK design, that their reactors had better containments, that the Soviet safety culture was deficient. All these statements were true, and Japan did not have another Chernobyl. They had Fukushima. Nuclear accidents do not repeat themselves exactly from one country to the next. The industry does learn and improve. What does repeat itself is the human inability to foresee the worst that can happen. That and the reluctance to spend the money to guard against combinations of events that are extremely unlikely at any one reactor over its lifetime but almost inevitable over a large population of reactors operating for many decades. So regulators and plant designers compromise, sometimes for want of imagination, sometimes to avoid costs. In normal times, careers are advanced by shortening licensing and construction times, not by finding new safety concerns. In 1972, a U.S. safety reviewer recommended that the U.S. stop licensing the type of containment that we now believe failed at Fukushima, a type also in use at many U.S. reactors. The official to whom he made this recommendation passed it on to his superior with a note that did not challenge the technical points. Indeed, it called the idea of banning pressure suppression containments an attractive one in some ways but concluded, the acceptance of (these)

1

Adjunct Professor, Vermont Law School; Member, Senior Policy Advisory Council, China Sustainable Energy Project; former Commissioner, U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission

containment concepts by all elements of the nuclear field..is firmly established in the conventional wisdom. Reversal of this hallowed policy.could well be the end of nuclear power. It would throw into question the continued operation of licensed plants, would make unlicensable (many) plants now in review and would generally create more turmoil than I can stand thinking about.2 No further action was taken with regard to the memorandum, though some of the problems with that containment design were addressed in later years. A hydrogen explosion at Three Mile Island was contained by the different containment structure in use at that site, but explosions of hydrogen that escaped the pressure suppression containments in use at Fukushima destroyed four reactor buildings, exposing the spent fuel pools and permitting a great deal of radiation to escape. The official who made the U.S. recommendation to ban Fukushima type containments continued to work at in nuclear regulation, though in relative obscurity. The official who rejected the concerns later became the chairman of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and served as a director of a utility that owned nuclear power plants. * * *

China has the worlds most ambitious nuclear construction program. Over the last decade, eleven new reactors have begun to operate. Another 27 are under construction. Current planning seems to contemplate nuclear capacity at least equal to the 100 gigawatts in the U.S. by 2030.3 The Chinese nuclear program includes several different designs. China has not followed the lead of France in choosing to standardize its program around a single design. As a result it will have the benefit of experience with many reactor types but also like the U.S. forty years ago - the regulatory and construction challenges of dealing simultaneously with several different reactor designs. By way of comparison, the U.S. put a total of 120 reactors into operation in the 39 years between 1957 and 1996, most of them before 1985. About the same number of plants were cancelled. At

2

Daniel Ford, The Cult of the Atom: The Secret Papers of the Atomic Energy Commission, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1982, pp. 193-4. 3 Businessweek, December 2, 2010. http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/10_50/b4207015606809.htm

its peak the U.S. program had more than 100 reactors under construction. Most were one of a kind. So the U.S. program was both larger and even more difficult to manage than the one now being undertaken by China. The U.S. experience in scaling up a major program involving several designs on a small base of experience led to an economic fiasco of cost overruns, plant cancellations and poor operation from which the industry has still not recovered. New nuclear reactors still cost far too much to compete effectively in U.S. power markets, and U.S. private investors want no part of the risks of new nuclear units. Even before the accident at Fukushima most of the 30 new reactors thought to be likely in the U.S. by 2020 had been cancelled or very substantially delayed. This experience need not be repeated in China, but it is cause for caution. China has even higher demand growth rates than the U.S. expected (but did not achieve) in the 1980s. In addition, the world now has far more experience with nuclear power construction and operation. Still, this additional experience is only helpful to a point. Rapid nuclear program growth still poses immense challenges in quality control, in training of qualified personnel, in creating effective regulatory institutions and in vigilantly analyzing both nuclear operating experience and natural disasters. It will always be easy to use hindsight to see how a catastrophe like Fukushima could have been avoided. A much harder task is to create and empower regulatory and quality control organizations with the strength wisdom and independence to take the necessary action before the accident happens. * * *

At the time that the Fukushima units were built, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission did not consider accidents that overwhelmed all reactor cooling systems to be credible events. Consequently, nuclear plant owners were not required to guard against them. Here are some events that were once thought by regulators and by the nuclear industry in the United States and in Japan to be so unlikely that no precautionary action needed to be taken: An earthquake of level 9.0 on the Richter scale A tsunami exceeding 10 meters in height

Loss of all off-site power accompanied by failure of multiple diesel generators lasting more than eight hours. Uncovering and overheating of fuel rods to such an extent that large quantities of hydrogen were released by the interaction of zirconium with the cooling water

Failure of the containments to contain the hydrogen Multiple hydrogen explosions in the reactor buildings Loss of coolant and fuel failure in spent fuel pools Further uncovering and overheating of nuclear fuel to such an extent that the fuel melted and fell to the bottom of the pressure vessels Fuel melting through the pressure vessels and into the reactor containments Escape of a significant fraction of the radioisotopes from the containments into the reactor buildings and from there into the environment. Evacuation of large numbers of people from around a nuclear power plant site Evacuation of people from around a nuclear power plant site needing to be conducted in the immediate aftermath of a natural disaster

Each of these twelve impossible events occurred (some more than once) during the first few days of the accident at Fukushima. Because they did, about one percent of the worlds nuclear capacity was destroyed on worldwide television. Also destroyed was the credibility of a regulatory regime that had theretofore been considered one of the best in the world. To learn and apply the lessons of a nuclear accident several steps are necessary. The accident must first be brought under control. Then a chronology of how the accident actually unfolded must be prepared. Then that accident sequence must be carefully and rigorously analyzed to determine basic causes, as well as effects and consequences. Only then can one prepare conclusions with regard to necessary reforms. Finally, these conclusions must be translated into revised regulatory requirements, with a firm schedule for their implementation. Since the accident at Fukushima is not yet under control, even the first of these steps has not been accomplished. Of course, analysis based on what is known can go forward, but it cannot be

considered complete or definitive in the absence of a definitive accident sequence. We are years away from being able to say that we know all of the lessons of Fukushima. One lesson is clear now, however. All safety regulatory systems in countries willing to build nuclear reactors will need to distinguish events that must be defended against from those deemed so unlikely as to be beyond regulatory concern. This is a solemn and a critical process. It cannot be hampered by complacency, by corruption, by a mistaken sense that everything is so safe already that costly new safety measures justify a prohibitively heavy burden of proof on the person proposing them. No precautionary measure will approach the cost that the Fukushima accident is certain to impose on the nuclear industry, to say nothing of the people of Japan.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Evaluation of The Epa Selected Remedy For Operable Unit-1 (Ou-1) - AppendixDocumento78 pagineEvaluation of The Epa Selected Remedy For Operable Unit-1 (Ou-1) - AppendixEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation of The Selected Remedy For Operable Unit-1 at The West Lake Landfill, July 20, 2016Documento10 pagineEvaluation of The Selected Remedy For Operable Unit-1 at The West Lake Landfill, July 20, 2016EnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 20 - Redaction of Information Released by TEPCODocumento6 pagineExhibit 20 - Redaction of Information Released by TEPCOEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 19 - Redaction of Recommendations Shared With IndustryDocumento15 pagineExhibit 19 - Redaction of Recommendations Shared With IndustryEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Pages From C147359-02X - March 17th, 2011 - Special Lawyers Group Tackled Legal Issues Arising From Fukushima Disaster Response For White HouseDocumento8 paginePages From C147359-02X - March 17th, 2011 - Special Lawyers Group Tackled Legal Issues Arising From Fukushima Disaster Response For White HouseEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 14 - Redaction of OPA Talking PointsDocumento11 pagineExhibit 14 - Redaction of OPA Talking PointsEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 21 - Sample Redacted MaterialsDocumento29 pagineExhibit 21 - Sample Redacted MaterialsEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Pages From C147216-02X - March 19th, 2011 - NRC NARAC Models of Fukushima Daiichi Disaster Did Not Model All Available RadionuclidesDocumento14 paginePages From C147216-02X - March 19th, 2011 - NRC NARAC Models of Fukushima Daiichi Disaster Did Not Model All Available RadionuclidesEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Pages From C147216-02X - March 15th, 2011 - Navy Tried To Get Dosimeters For All Sailors On USS Ronald Reagan After Fukushima DisasterDocumento50 paginePages From C147216-02X - March 15th, 2011 - Navy Tried To Get Dosimeters For All Sailors On USS Ronald Reagan After Fukushima DisasterEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 7 - Bruce Watson CommunicationsDocumento64 pagineExhibit 7 - Bruce Watson CommunicationsEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 17 - Redaction of Payroll InformationDocumento7 pagineExhibit 17 - Redaction of Payroll InformationEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 16 - Redaction of Material Derived From Public DocumentsDocumento9 pagineExhibit 16 - Redaction of Material Derived From Public DocumentsEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 18 - Redaction of Information Shared With IndustryDocumento17 pagineExhibit 18 - Redaction of Information Shared With IndustryEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 11 - Redacted Presentation From Nuclear Energy System Safety Division of JNESDocumento26 pagineExhibit 11 - Redacted Presentation From Nuclear Energy System Safety Division of JNESEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 12 - Potential Near-Term Options To Mitigate Contaminated Water in Japan's Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear PlantDocumento57 pagineExhibit 12 - Potential Near-Term Options To Mitigate Contaminated Water in Japan's Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear PlantEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 9 - Redaction of NRC PresentationDocumento12 pagineExhibit 9 - Redaction of NRC PresentationEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 13 - Redacted Generic EmailDocumento28 pagineExhibit 13 - Redacted Generic EmailEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 15 - Redaction of Time-Off RequestDocumento1 paginaExhibit 15 - Redaction of Time-Off RequestEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 8 - Document Search DOE Doc EGG-M-09386 CONF-860724-14Documento19 pagineExhibit 8 - Document Search DOE Doc EGG-M-09386 CONF-860724-14EnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 1 - Redaction of Answers To Bill Dedman's QuestionsDocumento10 pagineExhibit 1 - Redaction of Answers To Bill Dedman's QuestionsEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 6 - PMT Request of Realistic Up-To-Date Estimation of Source TermsDocumento6 pagineExhibit 6 - PMT Request of Realistic Up-To-Date Estimation of Source TermsEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 10 - Redacted CommunicationsDocumento3 pagineExhibit 10 - Redacted CommunicationsEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- March 21st, 2011 - A Delta Pilot's Perspective On His Approach To Tokyo in The Wake of The March 11th Earthquake - Pages From C146330-02X - Partial - Group Letter DO.-2Documento2 pagineMarch 21st, 2011 - A Delta Pilot's Perspective On His Approach To Tokyo in The Wake of The March 11th Earthquake - Pages From C146330-02X - Partial - Group Letter DO.-2EnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 5 - Comparison of Intervention Levels For Different CountriesDocumento11 pagineExhibit 5 - Comparison of Intervention Levels For Different CountriesEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 4 - Answers From DOE in Response To TEPCODocumento18 pagineExhibit 4 - Answers From DOE in Response To TEPCOEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- March 14th, 2011 - TEPCO Requests US Embassy Help Extinguish Fire at Unit 4 - Pages From C146301-02X - Group DK-18Documento2 pagineMarch 14th, 2011 - TEPCO Requests US Embassy Help Extinguish Fire at Unit 4 - Pages From C146301-02X - Group DK-18EnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 3 - Documents Shared With International PartiesDocumento19 pagineExhibit 3 - Documents Shared With International PartiesEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibit 2 - Agendas Largely RedactedDocumento13 pagineExhibit 2 - Agendas Largely RedactedEnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- March 17th, 2011 - Hopefully This Would Not Happen Here - Pages From C146257-02X - Group DL. Part 1 of 1-2Documento1 paginaMarch 17th, 2011 - Hopefully This Would Not Happen Here - Pages From C146257-02X - Group DL. Part 1 of 1-2EnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- March 22nd, 2011 - Core Melt at Fukushima Unit 1 From 11 To 12 March 2011 - Pages From C146301-02X - Group DK-30Documento3 pagineMarch 22nd, 2011 - Core Melt at Fukushima Unit 1 From 11 To 12 March 2011 - Pages From C146301-02X - Group DK-30EnformableNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Project Report On Solar Module Manufacturing UnitDocumento9 pagineProject Report On Solar Module Manufacturing UnitEIRI Board of Consultants and PublishersNessuna valutazione finora

- ARAÑA MECC486 P2 M4AssignmentDocumento15 pagineARAÑA MECC486 P2 M4AssignmentKent LabajoNessuna valutazione finora

- Panasonic HIT 240S Data Sheet-1Documento2 paginePanasonic HIT 240S Data Sheet-1Jesus David Muñoz RoblesNessuna valutazione finora

- cycleCCplant PDFDocumento19 paginecycleCCplant PDFJohn Bihag100% (1)

- Maximizing Solar Energy Collection Through TrackingDocumento3 pagineMaximizing Solar Energy Collection Through Trackingtakethebow runNessuna valutazione finora

- Boiler TypesDocumento14 pagineBoiler Typesaecsuresh35Nessuna valutazione finora

- TPP Equipment and ServicesDocumento24 pagineTPP Equipment and ServicesmanojkumarNessuna valutazione finora

- AUB MECH-410 Lab IV - Measuring PV Cell EfficiencyDocumento5 pagineAUB MECH-410 Lab IV - Measuring PV Cell EfficiencyZakNessuna valutazione finora

- CHP-and Power PlantsDocumento9 pagineCHP-and Power Plantschakerr6003Nessuna valutazione finora

- Three Mile Island (Ethical Engineering Study)Documento23 pagineThree Mile Island (Ethical Engineering Study)Badrulshahputra Basha89% (9)

- 9e ChinaDocumento7 pagine9e Chinanabil160874Nessuna valutazione finora

- Complex Engineering Problem: Mohammad Hussain Submitted To: BSME: 18-22 Roll: 19 Dr. Rab NawazDocumento11 pagineComplex Engineering Problem: Mohammad Hussain Submitted To: BSME: 18-22 Roll: 19 Dr. Rab NawazMohammad HussainNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 5 - Steam Power Plant ReviewerDocumento9 pagineChapter 5 - Steam Power Plant ReviewerKyle YsitNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is The Meaning of Diesel EngineDocumento31 pagineWhat Is The Meaning of Diesel EngineaguzkupridNessuna valutazione finora

- Photovoltaics: Basic Design Principles and Components: Introduction To Photovoltaic (Solar Cell) SystemsDocumento10 paginePhotovoltaics: Basic Design Principles and Components: Introduction To Photovoltaic (Solar Cell) SystemsSingam Sridhar100% (1)

- Biomass DevicesDocumento2 pagineBiomass DevicesGodwinNessuna valutazione finora

- Manual de Ford Edge Timming ChainDocumento17 pagineManual de Ford Edge Timming ChainJorge Antonio GuillenNessuna valutazione finora

- Engine Noise at Idle Goes Away When AcceleratingDocumento2 pagineEngine Noise at Idle Goes Away When AcceleratingYosephBerhanuNessuna valutazione finora

- Limit Table According To ISO (10816-3 and 14694)Documento1 paginaLimit Table According To ISO (10816-3 and 14694)Muhammad Haroon67% (3)

- 1.1 Function of Different Parts of Diesel EngineDocumento1 pagina1.1 Function of Different Parts of Diesel EngineIvan Timothy Rosales Calica75% (8)

- Sulzer Rta72U Diesel Engine - Operational Guideline Sulzer EngineDocumento5 pagineSulzer Rta72U Diesel Engine - Operational Guideline Sulzer EngineAayush Agrawal0% (1)

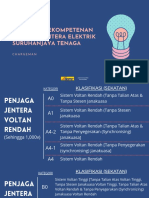

- EIU Sarawak Chargeman Competency CategoriesDocumento9 pagineEIU Sarawak Chargeman Competency CategoriesAbun ParadoxsNessuna valutazione finora

- Fiche 4 2 Solar Photovoltaic PDFDocumento18 pagineFiche 4 2 Solar Photovoltaic PDFhitosnapNessuna valutazione finora

- Vibrations in A Francis Turbine A Case StudyDocumento4 pagineVibrations in A Francis Turbine A Case Studybukit_guestNessuna valutazione finora

- Solar Panel Design (1.1.19)Documento9 pagineSolar Panel Design (1.1.19)jiguparmar1516Nessuna valutazione finora

- Panel Szyl-P25-18cDocumento2 paginePanel Szyl-P25-18cEmiliano NiderhausNessuna valutazione finora

- Nozzle Problems For PracticeDocumento3 pagineNozzle Problems For Practicestmurugan100% (1)

- Developing Manufacturing Capabilities To Support Local Content in Indonesia Solar PV IndustryDocumento18 pagineDeveloping Manufacturing Capabilities To Support Local Content in Indonesia Solar PV IndustryAgus SupriyonoNessuna valutazione finora

- Alstom Editorial Guide Thailand To Showcase Latest Upgrade of Alstom S Gt26 in Combined Cycle - Whitepaperpdf.renderDocumento4 pagineAlstom Editorial Guide Thailand To Showcase Latest Upgrade of Alstom S Gt26 in Combined Cycle - Whitepaperpdf.renderEngr Jonathan O OkoronkwoNessuna valutazione finora

- Boiler With Mountings and AccessoriesDocumento67 pagineBoiler With Mountings and AccessoriesYashvir Singh100% (1)