Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Italian Set

Caricato da

Jennifer SmithDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Italian Set

Caricato da

Jennifer SmithCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The Baroque era Opera did not remain confined to court audiences for long.

In 1637, the idea of a "season" (Carnival) of publicly attended operas supported by ticket sales emerged in Venice. Monteverdi had moved to the city from Mantua and composed his last operas, Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria and L'incoronazione di Poppea, for the Venetian theatre in the 1640s. His most important follower Francesco Cavalli helped spread opera throughout Italy. In these early Baroque operas, broad comedy was blended with tragic elements in a mix that jarred some educated sensibilities, sparking the first of opera's many reform movements, sponsored by Venice's Arcadian Academy which came to be associated with the poet Metastasio, whose libretti helped crystallize the genre of opera seria, which became the leading form of Italian opera until the end of the 18th century. Once the Metastasian ideal had been firmly established, comedy in Baroque-era opera was reserved for what came to be called opera buffa. Before such elements were forced out of opera seria, many libretti had featured a separately unfolding comic plot as sort of an "opera-within-an-opera." One reason for this was an attempt to attract members of the growing merchant class, newly wealthy, but still less cultured than the nobility, to the public opera houses. These separate plots were almost immediately resurrected in a separately developing tradition that partly derived from the commedia dell'arte, a long-flourishing improvisatory stage tradition of Italy. Just as intermedi had once been performed in-between the acts of stage plays, operas in the new comic genre of "intermezzi", which developed largely in Naples in the 1710s and '20s, were initially staged during the intermissions of opera seria. They became so popular, however, that they were soon being offered as separate productions. Opera seria was elevated in tone and highly stylised in form, usually consisting of secco recitative interspersed with long da capo arias. These afforded great opportunity for virtuosic singing and during the golden age of opera seria the singer really became the star. The role of the hero was usually written for the castrato voice; castrati such as Farinelli and Senesino, as well as female sopranos such as Faustina Bordoni, became in great demand throughout Europe as opera seria ruled the stage in every country except France. Indeed, Farinelli was the most famous singer of the 18th century. Italian opera set the Baroque standard. Italian libretti were the norm, even when a German composer like Handel found himself writing for London audiences. Italian libretti remained dominant in the classical period as well, for example in the operas of Mozart, who wrote in Vienna near the century's close. Leading Italian-born composers of opera seria include Alessandro Scarlatti, Vivaldi and Porpora.[7] Reform: Gluck, the attack on the Metastasian ideal, and Mozart Opera seria had its weaknesses and critics. The taste for embellishment on behalf of the superbly trained singers, and the use of spectacle as a replacement for dramatic purity and unity drew attacks. Francesco Algarotti's Essay on the Opera (1754) proved to be an inspiration for Christoph Willibald Gluck's reforms. He advocated that opera seria had to return to basics and that all the various elementsmusic (both instrumental and vocal), ballet, and stagingmust be subservient to the overriding drama. Several composers of the period, including Niccol Jommelli and Tommaso Traetta, attempted to put these ideals into practice. The first to succeed however, was Gluck. Gluck strove to achieve a "beautiful simplicity". This is evident in his first reform opera, Orfeo ed Euridice, where his non-virtuosic vocal melodies are supported by simple harmonies and a richer orchestra presence throughout. Gluck's reforms have had resonance throughout operatic history. Weber, Mozart and Wagner, in particular, were influenced by his ideals. Mozart, in many ways Gluck's successor, combined a superb sense of drama, harmony, melody, and counterpoint to write a series of comedies, notably Cos fan tutte, The Marriage of Figaro, and Don Giovanni (in collaboration with Lorenzo Da Ponte) which remain among the most-loved, popular and well-known operas today. But Mozart's contribution to opera seria was more mixed; by his time it was dying away, and in spite of such fine works as Idomeneo and La clemenza di Tito, he would not succeed in bringing the art form back to life again.[8] Agrippina (opera) Agrippina (HWV 6) is an opera seria in three acts by George Frideric Handel, from a libretto by Cardinal Vincenzo Grimani. Composed for the 170910 Venice Carnevale season, the opera tells the story of Agrippina, the mother of Nero, as she plots the downfall of the Roman Emperor Claudius and the installation of her son as emperor. Grimani's libretto, considered one of the best that Handel set, is an "anti-heroic satirical comedy",[1] full of topical political allusions. Some analysts believe that it reflects the rivalry of Grimani with Pope Clement XI. Handel composed Agrippina at the end of a three-year visit to Italy. It premiered in Venice at the Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo on 26 December 1709, and was an immediate success. From its opening night it was given a then-unprecedented run of 27 consecutive performances, and received much critical acclaim. Observers were full of praise for the quality of the musicmuch of which, in keeping with the contemporary custom, had been borrowed and adapted from other works, including some from other composers. Despite the evident public enthusiasm for

the work, Handel did not promote further stagings. There were occasional productions in the years following its premiere but, when Handel's operas fell out of fashion in the mid-18th century, it and his other dramatic works were generally forgotten. In the 20th century, Handelian opera began a revival which, after productions in Germany, saw Agrippina premiered in Britain and in America. In recent years performances of the work have become more common, with innovative stagings at the New York City Opera and the London Coliseum in 2007. Modern critical opinion is that Agrippina is Handel's first operatic masterpiece, full of freshness and musical invention which have made it one of the most popular operas of the continuing Handel revival.[2] Composition history Handel's earliest opera compositions, in the German style, date from his Hamburg years, 170406, under the influence of Johann Mattheson.[3] In 1706 he travelled to Italy where he remained for three years, learning the Italian style of music and developing his compositional skills. Initially he stayed in Florence where he was introduced to Alessandro and Domenico Scarlatti, and where his first Italian opera was composed and performed.[4] This was Rodrigo (1707, original title Vincer se stesso la maggior vittoria), in which the Hamburg and Mattheson influences remained prominent.[3][4] The opera was not particularly successful, but was part of Handel's process of learning to compose opera in the Italian style and to set Italian words to music.[4] After Florence, Handel spent time in Rome, where the performance of opera was forbidden by Papal decree, [5] and in Naples. He was able to apply himself to the composition of cantata and oratorio; at that time there was little difference (apart from increasing length) between cantata, oratorio and opera, which are all based on the alternation of secco recitative and aria da capo.[6][7] Works from this period include Dixit Dominus, and the dramatic cantata Aci, Galatea e Polifemo, written in Naples. While in Rome, Handel had become acquainted with Cardinal Vincenzo Grimani, probably through Alessandro Scarlatti.[8] The Cardinal was a distinguished diplomat who wrote libretti in his spare time, and acted as an unofficial theatrical agent for the Italian royal courts. [9][10] He made Handel his protg, and gave him his libretto for Agrippina. It has been surmised that Handel took the libretto to Naples where he set it to music.[8] However, according to John Mainwaring, Handel's first biographer, it was written very rapidly after Handel's arrival in Venice in November 1709. This theory is supported by the autograph manuscript's Venetian paper.[11] Grimani arranged to present the opera in Venice, at his family-owned theatre, the Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo, as part of the 170910 Carnevale season.[2] A similar story had been used before, as the subject of Monteverdi's 1642 opera L'incoronazione di Poppea, but Grimani's libretto centred on Agrippina, a character who does not appear in Monteverdi's darker version.[9] This was Handel's second Italian opera, and probably his last composition in Italy.[12] Composing Agrippina In composing the opera Handel borrowed extensively from his earlier oratorios and cantatas, and from other composers including Reinhard Keiser, Arcangelo Corelli and Jean-Baptiste Lully.[13] This adapting and borrowing was common practice at the time, but its extent in Agrippina is greater than in almost all the composer's other major dramatic works.[13] The overture, which is a French-style two-part work with a "thrilling" allegro,[14] and all but five of the vocal numbers, are based on earlier works, in many cases after significant adaptation and reworking.[12] Examples of recycled material include Pallas's "Col raggio placido", which is based on Lucifer's aria from La resurrezione (1708), "O voi dell' Erebo", which was itself adapted from Reinhard Keiser's 1705 opera Octavia. Agrippina's aria "Non h cor che per amarti" was taken, almost entirely unadapted, from "Se la morte non vorr" in Handel's earlier dramatic cantata Qual ti reveggio, oh Dio (1707); Narcissus's "Sperer" is an adaptation of "Sai perch" from another 1707 cantata, Clori, Tirsi e Fileno; and parts of Nero's Act 3 aria "Come nube che fugge dal vento" are borrowed Handel's oratorio Il trionfo del tempo (all from 1707).[15] Later, some of Agrippina's music was used by Handel in his London operas Rinaldo (1711) and the 1732 version of Acis and Galatea, in each case with little or no change.[16] The first music by Handel heard in London may have been Agrippina's "Non h che", transposed into Alessandro Scarlatti's opera Pirro Dimitrio which was performed in London on 6 December 1710.[17] The Agrippina overture and other arias from the opera appeared in pasticcios performed in London between 1710 and 1714, with additional music provided by other composers.[18] Echoes of "Ti vo' giusta" (one of the few arias composed specifically for Agrippina) can be found in the air "He was despised", from Handel's Messiah (1742).[19] Two of the main male roles, Nero and Narcissus, were written for castrati, the "superstars of their day" in Italian opera.[2] The opera was revised significantly before and possibly during its run.[20] For example, in Act III Handel originally had Otho and Poppaea sing a duet, "No, no, ch'io non apprezzo", but he was dissatisfied with the music

and replaced the duet with two solo arias before the first performance. [21] Again, during the run Poppaea's aria "Ingannata" was replaced with another of extreme virtuosity,"Pur punir chi m'ha ingannata", either to emphasise Poppaea's new-found resolution at this juncture of the opera or, as is thought more likely, to flatter Scarabelli by giving her further opportunity to show off her vocal abilities. [20] The instrumentation for Handel's score follows closely that of all his early operas, and consists of two recorders, two oboes, two trumpets, three violins, two cellos, viola, timpani, contrabassoon and harpsichord. [22] By the later standards of Handel's London operas this scoring is light, but there are nevertheless what Dean and Knapp describe as "moments of splendour when Handel applies the full concerto grosso treatment."[23] Libretto Grimani's libretto avoids the "moralizing" tone of the later opera seria libretti written by acknowledged masters such as Metastasio and Zeno.[12] The favourable reception given to the opera may, according to critic Donald Jay Grout, owe much to Grimani's work in which "irony, deception and intrigue pervade the humorous escapades of its well-defined characters."[3] All the main characters, with the sole exception of Claudius's servant Lesbus, are historical, and the broad outline of the libretto draws heavily upon Tacitus's Annals and Suetonius' Life of Claudius.[12] It has been suggested that the comical, amatory character of the Emperor Claudius is a caricature of Pope Clement XI, to whom Grimani was politically opposed.[24] Certain aspects of this conflict are also reflected in the plot: the rivalry between Nero and Otho mirror aspects of the debate over the War of the Spanish Succession, in which Grimani supported the Habsburgs, and Pope Clement XI France and Spain.[9] The date of Agrippina's first performance, about which there was at one time some uncertainty, has been confirmed by a manuscript newsletter as 26 December 1709.[11] The cast consisted of some of Northern Italy's leading singers of the day, including Antonio Carli in the lead bass role; Margherita Durastanti, who had recently sung the role of Mary Magdalene in Handel's La resurrezione; and Diamante Scarabelli, whose great success at Bologna in the 1697 pasticcio Perseo inspired the publication of a volume of eulogistic verse entitled La miniera del Diamante.[25][26] Agrippina proved extremely popular, and established Handel's international reputation.[26] Its original run was for 27 performances, extraordinarily long for that time.[25] Handel's biographer John Mainwaring wrote of the first performance: "The theatre at almost every pause resounded with shouts of Viva il caro Sassone! ('Long live the beloved Saxon!') They were thunderstruck with the grandeur and sublimity of his style, for they had never known till then all the powers of harmony and modulation so closely arranged and forcibly combined." [27] Many others recorded overwhelmingly positive responses to the work. [14] Between 1713 and 1724 there were productions of Agrippina in Naples, Hamburg, and Vienna, although Handel himself never revived the opera after its initial run.[28] The Naples production included additional music by Francesco Mancini.[29] [edit] Later performances In the late 18th and throughout the 19th century, Handel's operas fell into obscurity, and none were staged between 1754 and 1920.[30] However, when interest in Handel's operas awakened in the 20th century, Agrippina received several revivals, beginning with a 1943 production at Handel's birthplace, Halle, under conductor Richard Kraus at the Halle Opera House. In this performance the alto role of Otho, composed for a woman, was changed into a bass accompanied by English horns, "with calamitous effects on the delicate balance and texture of the score".[31] The Radio Audizioni Italiane produced a live radio broadcast of the opera on 25 October 1953, marking the first time that Agrippina was communicated in a medium other than the stage. The cast included Magda Lszl in the title role and Mario Petri as Claudius, and the performance was conducted by Antonio Pedrotti.[32] A 1958 performance in Leipzig, and several more stagings in Germany, preceded the British premire of the opera at Abingdon, Oxfordshire, in 1963.[2][33] In 1965 it was performed at Ledlanet, Scotland. In 1983 the opera returned to Venice, for a performance under Christopher Hogwood at the Teatro Malibran.[33] In the United States a concert performance had been given on 16 February 1972 at the Academy of Music in Philadelphia,[34] but the opera's first fully staged American performance was in Fort Worth, Texas in 1985.[35] That same year it reached New York, with a concert performance at Alice Tully Hall, the opera still being described at that time as a "genuine rarity".[36] The Fort Worth performance was quickly followed by further American stagings in Iowa City and Boston.[33] The so-called "Early Music Movement", which advocates historically accurate performances of Baroque and early works, promoted two major productions of Agrippina in 1985 and 1991 respectively. Both were in Germany, the first was in the Schlosstheater Schwetzingen, the other at the Gttingen International Handel Festival.[9] [edit] Contemporary revivals There have been numerous productions in the 21st century, including a 2002 "ultramodern" staging by director Lillian Groag at the New York City Opera. This production, revived in 2007, was described by the New York Times critic as "odd ... presented as broad satire, a Springtime for Hitler version of I, Claudius", although the musical performances were generally praised.[37] In Britain, the English National Opera (ENO) staged an English-

language version in February 2007, directed by David McVicar, which received a broadly favourable critical response, although critic Fiona Maddocks identified features of the production that diminished the work: "Music so witty, inventive and humane requires no extra gilding". [38][39] These recent revivals have used countertenors in the roles written for castrati, as did the 1997 Gardiner recording. [37][40] [edit] Synopsis [edit] Act 1 On hearing the news that her husband, the Emperor Claudius, has died in a storm at sea, Agrippina plots to secure the throne for Nero, her son by a previous marriage. Nero is unenthusiastic about this project, but assents to his mother's wishes ("Con saggio tuo consiglio"). Agrippina obtains the support of her two freedmen, Pallas and Narcissus, who hail Nero as the new Emperor before the Senate. With the Senate's assent Agrippina and Nero begin to ascend the throne, but the ceremony is interrupted by the entrance of Claudius's servant Lesbus. He announces that his master is alive ("Allegrezza! Claudio giunge!"), saved from death by Otho, the commander of the army. Otho himself confirms the story, and reveals that Claudius has promised him the throne as a mark of gratitude. Agrippina is confounded, until Otho secretly confides to her that he loves the beautiful Poppaea more than he desires the throne. Agrippina, aware that Claudius also loves Poppaea, sees a new opportunity of furthering her ambitions for Nero. She goes to Poppaea and tells her, falsely, that Otho has struck a bargain with Claudius whereby he, Otho, gains the throne but gives Poppaea to Claudius. Agrippina advises Poppaea to turn the tables on Otho by telling the Emperor that Otho has ordered her to refuse Claudius's attentions. This, Agrippina believes, will make Claudius revoke his promise to Otho of the throne. Poppaea believes Agrippina. When Claudius arrives at Poppaea's house she reveals what she believes is Otho's treachery. Claudius departs in fury, while Agrippina cynically consoles Poppaea by declaring that their friendship will never be broken by deceit ("Non h cor che per amarti"). [edit] Act 2 Pallas and Narcissus realize that Agrippina has tricked them into supporting Nero, and decide to have no more to do with her. Otho arrives, nervous about his forthcoming coronation ("Coronato il crin d'allore"), followed by Agrippina, Nero and Poppaea, who have come to greet Claudius. All combine in a triumphal chorus ("Di timpani e trombe"), as Claudius enters. Each in turns pays tribute to the Emperor, but Otho is coldly rebuffed as Claudius denounces him as a traitor. Otho is devastated, and appeals to Agrippina, Poppaea, and Nero for support, but they all reject him, leaving him in bewilderment and despair ("Otton, qual portenso fulminare" followed by "Vol che udite il mio lamenti"). However, Poppaea is touched by her former beloved's grief, and wonders if he might not be innocent ("Bella pur nel mio diletto"). She devises a plan, which involves pretended sleep and, when Otho approaches her, sleep-talking what Agrippina has told her earlier. Otho, as intended, overhears her and fiercely protests his innocence. He convinces Poppaea that Agrippina has deceived her. Poppaea swears revenge ("Ingannata una sol volta"), [45] but is distracted when Nero comes forward and declares his love for her. Meanwhile Agrippina has lost the support of Pallas and Narcissus, but manages to convince Claudius that Otho is still plotting to take the throne. She advises him that he should end Otho's ambitions once and for all by abdicating in favour of Nero. Claudius, eager to be with Poppaea again, agrees. [edit] Act 3 Poppaea now plans some deceit of her own, in an effort to divert Claudius's wrath from Otho with whom she is now reconciled. She hides Otho in her bedroom with instructions to listen carefully. Soon Nero arrives to press his love on her ("Coll ardor del tuo bel core"), but she tricks him into hiding as well. Then Claudius enters; Poppaea tells him that he had earlier misunderstood her: it was not Otho but Nero who had ordered her to reject Claudius. To prove her point she asks Claudius to pretend to leave, then she summons Nero who, thinking Claudius has gone, resumes his passionate wooing of Poppaea. Claudius suddenly reappears, and angrily dismisses the crestfallen Nero. After Claudius departs, Poppaea brings Otho out of hiding and the two express their everlasting love in separate arias.[46] At the palace, Nero tells Agrippina of his troubles, and decides to renounce love for political ambition ("Come nubbe che fugge dal vento"). But Pallas and Narcissus have by now revealed Agrippina's original plot to Claudius, so that when Agrippina urges the Emperor to yield the throne to Nero, he accuses her of treachery. She then claims that her efforts to secure the throne for Nero had all along been a ruse to safeguard the throne for Claudius ("Se vuoi pace"). Claudius believes her; nevertheless, when Poppaea, Otho, and Nero arrive, Claudius announces that Nero and Poppaea will marry, and that Otho shall have the throne. No one is satisfied with this arrangement, as their desires have all changed, so Claudius in a spirit of reconciliation reverses his judgement, giving Poppaea to Otho and the throne to Nero.[47] He then summons the goddess Juno, who descends to pronounce a general blessing ("V'accendano le tede i raggi delle stelle").

[edit] Music [edit] Style Stylistically, Agrippina follows the standard pattern of the era by alternating recitative and da capo arias. In accordance with 18th-century opera convention the plot is mainly carried forward in the recitatives, while the musical interest and exploration of character takes place in the ariasalthough on occasion Handel breaks this mould by using arias to advance the action.[49] With one exception the recitative sections are secco ("dry"), where a simple vocal line is accompanied by continuo only.[50] The anomaly is Otho's "Otton, qual portentoso fulmine", where he finds himself robbed of the throne and deserted by his beloved Poppaea; here the recitative is accompanied by the orchestra, as a means of highlighting the drama. Dean and Knapp describe this, and the Otho's aria which follows, as "the peak of the opera".[51] The 19th-century musical theorist Ebenezer Prout singles out Agrippina's "Non h che per amarti" for special praise. He points out the range of instruments used for special effects, and writes that "an examination of the score of this air would probably astonish some who think Handel's orchestration is wanting in variety."[52] Handel made more use than was then usual of orchestral accompaniment in arias, but in other respects Agrippina is more typical of an older operatic tradition. For the most part the arias are brief, there are only two short ensembles, and in the quartet and the trio the voices are not heard together.[49][53] However, Handel's basic style when had matured, and would change very little in the next 30 years, [30] a point reflected in the reviews of the Tully Hall performance of Agrippina in 1985, which refer to a "string of melodious aria and ensembles, any of which could be mistaken for the work of his mature London years". [36] [edit] Character Of the main characters, only Otho is not morally contemptible. Agrippina is an unscrupulous schemer; Nero, while not yet the monster he would become, is pampered and hypocritical; Claudius is pompous, complacent, and something of a buffoon, while Poppaea, the first of Handel's sex kittens, is also a liar and a flirt.[54] The freedmen Pallas and Narcissus are self-serving and salacious.[55] All, however, have some redeeming features, and all have arias that express genuine emotion. The situations in which they find themselves are sometimes comic, but never farcicallike Mozart in the Da Ponte operas, Handel avoids laughing at his characters.[55] In Agrippina the da capo aria is the musical form used to illustrate character in the context of the opera. [56] The first four arias of the work exemplify this: Nero's "Con raggio", in a minor key and with a descending figure on the key phrase "il trono ascendero" ("I will ascend the throne") characterises him as weak and irresolute.[56] Pallas's first aria "La mia sorte fortunata", with its "wide-leaping melodic phrasing" introduces him as a bold, heroic figure, contrasting with his rival Narcissus whose introspective nature is displayed in his delicate aria "Volo pronto" which immediately follows.[56] Agrippina's introductory aria "L'alma mia" has a mock-military form which reflects her outward power, while subtle musical phrasing establishes her real emotional state.[56] Poppaea's arias are uniformly light and rhythmic, while Claudius's short love song "Vieni O cara" gives a glimpse of his inner feelings, and is considered one of the gems of the score.[57] [edit] Irony Grimani's libretto is full of irony, which Handel reflects in the music. His settings sometimes illustrate both the surface meaning, as characters attempt to deceive each other, and the hidden truth. For instance, in her Act I aria "Non h che per amarti" Agrippina promises Poppaea that deceit will never mar their new friendship, while tricking her into ruining Otho's chances for the throne. Handel's music illuminates her deceit in the melody and minor modal key, while a simple, emphasised rhythmic accompaniment hints at clarity and openness. [58] In Act III, Nero's announcement that his passion is ended and that he will no longer bound by it (in "Come nubbe che fugge dal vento") is set to bitter-sweet music which suggests that he is deceiving himself.[59] In Otho's "Coronato il crin" the agitated nature of the music is the opposite of what the "euphoric" tone of the libretto suggests. [49] Contrasts between the force of the libretto and the emotional colour of the actual music would develop into a constant feature of Handel's later London operas.[49] Agrippina is considered Handel's first operatic masterpiece;[1] according to Winton Dean it has few rivals for its "sheer freshness of musical invention".[19] Grimani's libretto has also come in for much praise: The New Penguin Opera Guide describes it as one of the best Handel ever set, and praises the "light touch" with which the characters are vividly portrayed.[1] Agrippina as a whole is, in the view of scholar John E. Sawyer, "among the most convincing of all the composer's dramatic works".[13]

Paride ed Elena Paride ed Elena (Paris and Helen) is an opera by Christoph Willibald Gluck, the third and final of his Italian

reformist works, following Orfeo ed Euridice and Alceste. Like its predecessors, its libretto was written by Ranieri

de' Calzabigi. The opera tells the story of the events between the Judgment of Paris and the flight of Paris and Helen to Troy. It was premiered at the Burgtheater in Vienna on 3 November 1770. [edit] Synopsis The hero Paris is in Sparta, having chosen Aphrodite above Hera and Athena, sacrificing to Aphrodite and seeking, with the encouragement of Erasto, the love of Helen. Paris and Helen meet at her royal palace and each is struck by the other's beauty. She calls on him to judge an athletic contest and when asked to sing he does so in praise of her beauty, admitting the purpose of his visit is to win her love. She dismisses him. In despair Paris now pleads with her, and she begins to give way. Eventually, through the intervention of Erasto, who now reveals himself as Cupid, she gives way, but Pallas Athene (Athena) now warns them of sorrow to come. In the final scene Paris and Helen make ready to embark for Troy. Paride ed Elena (Paris and Helen) is the third of Gluck's so-called reform operas for Vienna, following Alceste (Alcestis) and Orfeo ed Euridice (Orpheus and Eurydice), and the least often performed of the three. Arias from the opera that enjoy an independent concert existence include Paris's minor-key declaration of love, O del mio dolce ardor (O of my gentle love), in the first act. His second aria is Spiagge amate (Beloved shores). In the second act, again in a minor key, Paris fears that he may lose Helen in Le belle imagini (The fair semblance) and in the fourth would prefer death to life without Helen, Di te scordarmi, e vivere (To forget you and to live). The rle of Paris offers difficulties of casting, written, as it was, for a relatively high castrato voice. Arias of Paris have been adapted by tenors, with transposition an octave lower, or appropriated by sopranos and mezzo-sopranos. GLUCK: Paride ed Elena Paride ed Elena: Dramma per musica in five acts. Christoph Willibald Gluck: Paride ed Elena Magdalena Kozena (Paride), Susan Gritton (Elena), Carolyn Sampson (Amore), Gillian Webster (Pallade), Gabrieli Consort & Players, directed by Paul McCreesh. Live performance, 23 October 2003, Cit de la Musique, Paris Music composed by Christoph Willibald Gluck. Libretto by Ranieri deCalzabigi. First Performance: 3 November 1770, Burgtheater, Vienna Setting: Sparta before the Trojan War. Background: The last of Glucks so-called reform operas, Paride ed Elena encompasses the events between The Judgment of Paris and the flight of Paris and Helen to Troy. According to the Cyprea: Zeus plans with Themis to bring about the Trojan war. Strife arrives while the gods are feasting at the marriage of Peleus and starts a dispute between Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite as to which of them is fairest. The three are led by Hermes at the command of Zeus to Alexandrus [Paris] on Mount Ida for his decision, and Alexandrus, lured by his promised marriage with Helen, decides in favour of Aphrodite. Paris deserts the nymph Oenone and proceeds to Sparta to claim Helen, the wife of Menelaus. Following the Greek custom to [h]ave Respect for one in need of house and hospitality, Menelaus welcomes Paris as his guest. Paris thereupon seduces Helen. Initially outraged, Helen ultimately takes flight with Paris to Troy. The abduction of Helen leads to the Trojan War immortalized in Homers Iliad. Ironically, Paris dies from battle wounds that Oenone refuses to cure. Helen, on the other hand, returns to Sparta where Menelaus restores her as his queen. Although condemned by the tragedians, others found Helen praiseworthy. Indeed, the great rhetorician, Isocrates, went so far as to argue: Apart from the arts and philosophic studies and all the other benefits which one might attribute to her and to the Trojan War, we should be justified in considering that it is owing to Helen that we are not the slaves of the barbarians. For we shall find that it was because of her that the Greeks became united in harmonious accord and organized a common expedition against the barbarians, and that it was then for the first time that Europe set up a trophy of victory over Asia; and in consequence, we experienced a change so great that, although in former times any barbarians who were in misfortune presumed to be rulers over the Greek cities (for example, Danaus, an exile from Egypt, occupied Argos, Cadmus of Sidon became king of Thebes, the Carians colonized the islands, and Pelops, son of Tantalus, became master of all the Peloponnese), yet after that war our race expanded so greatly that it took from the barbarians great cities and much territory. If, therefore, any orators wish to dilate upon these matters and dwell upon them, they will not be at a loss for material apart from what I have said, wherewith to praise Helen; on the contrary, they will discover many new arguments that relate to her.

Synopsis: Paris, having chosen Venus above Juno and Minerva, is in Sparta, sacrificing to Venus and seeking, now with the encouragement of Erasto, the love of Helen. Paris and Helen meet at her royal palace and each is struck by the other's beauty. She calls on him to judge an athletic contest and when asked to sing he does so in praise of her beauty, admitting the purpose of his visit is to win her love. She dismisses him. In despair Paris now pleads with her, and she begins to give way. Eventually, through the intervention of Erasto, who now reveals himself as Cupid, she gives way, but Pallas Athene (Minerva) now warns them of sorrow to come. In the final scene Paris and Helen make ready to embark for Troy.

The Marriage of Figaro

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For the Beaumarchais play, see The Marriage of Figaro (play). For the opera by Marcos Portugal (1799), see Marcos Portugal. Le nozze di Figaro, ossia la folle giornata (The Marriage of Figaro, or The Day of Madness), K. 492, is an opera buffa (comic opera) composed in 1786 in four acts by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, with a libretto in Italian by Lorenzo Da Ponte, based on a stage comedy by Pierre Beaumarchais, La folle journe, ou le Mariage de Figaro (1784). Beaumarchais' earlier play The Barber of Seville had already made a successful transition to opera in a version by Paisiello. Although Beaumarchais' Marriage of Figaro was at first banned in Vienna because of its satire of the aristocracy, considered dangerous in the decade before the French Revolution, Mozart and his librettist managed to get official approval for an operatic version which eventually achieved great success. [edit] Composition The opera was the first of three collaborations between Mozart and Da Ponte; their later collaborations were Don Giovanni and Cos fan tutte. It was Mozart who originally selected Beaumarchais' play and brought it to Da Ponte, who turned it into a libretto in six weeks, rewriting it in poetic Italian. Da Ponte strengthened the emotional content of the play, removing all of the original's political references. In particular, Da Ponte replaced Figaro's climactic speech against inherited nobility with an equally angry aria against unfaithful wives. Contrary to the popular myth, the libretto was approved by the Emperor, Joseph II, before any music was written by Mozart.[1] The Imperial Italian opera company paid Mozart 450 florins for the work;[2] this was three times his (low) salary for a year, when he had worked as a court musician in Salzburg (Solomon 1995). Da Ponte was paid 200 florins. [2] [edit] Performance history Figaro premiered at the Burgtheater in Vienna on 1 May 1786, the cast for which is included in the "Roles" section below. Mozart himself directed the first two performances, conducting seated at the keyboard, the custom of the day. Later performances were by Joseph Weigl.[3] The first production was given eight further performances, all in 1786.[4] Although the total of nine performances was nothing like the frequency of performance of Mozart's later success The Magic Flute, which for months was performed roughly every other day (Solomon 1995), the premiere is generally judged to have been a success. The applause of the audience on the first night resulted in five numbers being encored, seven on 8 May (Deutsch 1965, p. 272). Joseph II, who, in addition to his empire, was in charge of the Burgtheater, was concerned by the length of the performance and directed his aide Count Rosenberg as follows: "To prevent the excessive duration of operas, without however prejudicing the fame often sought by opera singers from the repetition of vocal pieces, I deem the enclosed notice to the public (that no piece for more than a single voice is to be repeated) to be the most reasonable expedient. You will therefore cause some posters to this effect to be printed."[5] The requested posters were printed up and posted in the Burgtheater in time for the third performance on 24 May (Deutsch 1965, p. 275). The newspaper Wiener Realzeitung carried a review of the opera in its issue of 11 July 1786. It alludes to interference probably produced by paid hecklers, but praises the work warmly: "Mozart's music was generally admired by connoisseurs already at the first performance, if I except only those whose self-love and conceit will not allow them to find merit in anything not written by themselves. The public, however did not really know on the first day where it stood. It heard many a bravo from unbiassed connoisseurs, but obstreperous louts in the uppermost storey exerted their hired lungs with all their might to deafen singers and audience alike with their St! and Pst; and consequently opinions were divided at the end of the piece.

Apart from that, it is true that the first performance was none of the best, owing to the difficulties of the composition. But now, after several performances, one would be subscribing either to the cabal or to tastelessness if one were to maintain that Herr Mozart's music is anything but a masterpiece of art. It contains so many beauties, and such a wealth of ideas, as can be drawn only from the source of innate genius."[6] The Hungarian poet Ferenc Kazinczy was in the audience for a May performance, and later remembered the powerful impression the work made on him: "[Nancy] Storace [see below], the beautiful singer, enchanted eye, ear, and soul. Mozart directed the orchestra, playing his fortepiano; the joy which this music causes is so far removed from all sensuality that one cannot speak of it. Where could words be found that are worthy to describe such joy?" [7] Joseph Haydn appreciated the opera greatly, writing to a friend that he heard it in his dreams. [8] In summer 1790 Haydn attempted to produce the work with his own company at Eszterhza, but was prevented from doing so by the death of his patron, Nikolaus Esterhzy (Landon & Jones 1988, p. 174). [edit] Other early performances The Emperor requested a special performance at his palace theater in Laxenburg, which took place in June 1786 (Deutsch 1965). The opera was produced in Prague starting in December 1786 by the Pasquale Bondini company. This production was a tremendous success; the newspaper Prager Oberpostamtszeitung called the work "a masterpiece" (Deutsch 1965, p. 281), and said "no piece (for everyone here asserts) has ever caused such a sensation." (Deutsch 1965, p. 280) Local music lovers paid for Mozart to visit Prague and hear the production; he listened on 17 January 1787, and conducted it himself on the 22nd (Deutsch 1965, p. 285). The success of the Prague production led to the commissioning of the next Mozart/Da Ponte opera, Don Giovanni, premiered in Prague in 1787; see Mozart and Prague. The work was not performed in Vienna during 1787 or 1788, but starting in 1789 there was a revival production.[9] For this occasion Mozart replaced both arias of Susanna with new compositions, better suited to the voice of Adriana Ferrarese del Bene who took the role. For Deh, vieni he wrote Al desio di chi t'adora "[come and fly] To the desire of [the one] who adores you" (K. 577) in July 1789, and for Venite, inginocchiatevi! he wrote Un moto di gioia "A joyous emotion", (K. 579), probably in mid-1790.[10] [edit] Contemporary reputation The Marriage of Figaro is now regarded as a cornerstone of the standard operatic repertoire, and it appears as number five on the Operabase list of the most-performed operas worldwide.[11] [edit] Roles The voice types which appear in this table are those listed in the original libretto. In modern performance practice, Cherubino is usually assigned to a mezzo-soprano (sometimes also Marcellina), Count Almaviva to a baritone, and Figaro to a bass-baritone.[12] Mozart (and his contemporaries) never used the terms "mezzo-soprano" or "baritone". Women's roles were listed as either "soprano" or "contralto", while men's roles were listed as either "tenor" or "bass". Many of Mozart's baritone and bass-baritone roles derive from the basso buffo tradition, where no clear distinction was drawn between bass and baritone, a practice that continued well into the 19th century. Similarly, mezzo-soprano as a distinct voice type was a 19th century development. [13] Modern re-classifications of the voice types for Mozartian roles have been based on analysis of contemporary descriptions of the singers who created those roles and their other repertoire, and on the role's tessitura in the score. Changes in role assignment can also result from modern preferences for contrasts in vocal timbre between two major characters, e.g. Fiordiligi and Dorabella in Cos fan tutte. Both roles were written for sopranos, although the slightly more low-lying role of Dorabella is now often sung by a mezzo.[14] [edit] Synopsis The Marriage of Figaro is a continuation of the plot of The Barber of Seville several years later, and recounts a single "day of madness" (la folle giornata) in the palace of the Count Almaviva near Seville, Spain. Rosina is now the Countess; Dr. Bartolo is seeking revenge against Figaro for thwarting his plans to marry Rosina himself; and Count Almaviva has degenerated from the romantic youth of Barber into a scheming, bullying, skirt-chasing baritone. Having gratefully given Figaro a job as head of his servant-staff, he is now persistently trying to obtain the favors of Figaro's bride-to-be, Susanna. He keeps finding excuses to delay the civil part of the wedding of his two servants, which is arranged for this very day. Figaro, Susanna, and the Countess conspire to embarrass the Count and expose his scheming. He responds by trying to compel Figaro legally to marry a woman old enough to

be his mother, but it turns out at the last minute that she is really his mother. Through Figaro's and Susanna's clever manipulations, the Count's love for his Countess is finally restored. Place: Count Almaviva's estate, Aguas-Frescas, three leagues outside Seville, Spain.[15] [edit] Overture The overture is especially famous and is often played as a concert piece. The musical material of the overture is not used later in the work, aside from two brief phrases during the Count's part in the terzetto Cosa sento! in act 1.[16] [edit] Act 1 A partly furnished room, with a chair in the centre. Figaro is happily measuring the space where the bridal bed will fit while Susanna is trying on her wedding bonnet in front of the mirror (in the present day, a more traditional French floral wreath or a modern veil are often substituted, often in combination with a bonnet, so as to accommodate what Susanna happily describes as her wedding "cappellino"). (Duet: Cinque, dieci, venti, trenta "Five, ten, twenty, thirty"). Figaro is quite pleased with their new room; Susanna far less so. She is bothered by its proximity to the Count's chambers: it seems he has been making advances toward her and plans on exercising his "droit du seigneur", the purported feudal right of a lord to bed a servant girl on her wedding night before her husband can sleep with her. The Count had the right abolished when he married Rosina, but he now wants to reinstate it. Figaro is livid and plans to outwit the Count (Cavatina: Se vuol ballare, signor contino "If you want to dance, sir Count"). Figaro departs, and Dr. Bartolo arrives with Marcellina, his old housekeeper. Marcellina has hired Bartolo as her counsel, since Figaro had once promised to marry her if he should default on a loan she had made to him, and she intends to enforce that promise. Bartolo, still irked at Figaro for having facilitated the union of the Count and Rosina (in The Barber of Seville), promises, in comical lawyer-speak, to help Marcellina (aria: La vendetta "Vengeance"). Bartolo departs, Susanna returns, and Marcellina and Susanna share an exchange of very politely delivered sarcastic insults (duet: Via, resti servita, madama brillante "After you, brilliant madam"). Susanna triumphs in the exchange by congratulating her rival on her impressive age. The older woman departs in a fury. Cherubino then arrives and, after describing his emerging infatuation with all women and particularly with his "beautiful godmother" the Countess (aria: Non so pi cosa son "I don't know anymore what I am"), asks for Susanna's aid with the Count. It seems the Count is angry with Cherubino's amorous ways, having discovered him with the gardener's daughter, Barbarina, and plans to punish him. Cherubino wants Susanna to ask the Countess to intercede on his behalf. When the Count appears, Cherubino hides behind a chair, not wanting to be seen alone with Susanna. The Count uses the opportunity of finding Susanna alone to step up his demands for favours from her, including financial inducements to sell herself to him. As Basilio, the slimy music teacher, arrives, the Count, not wanting to be caught alone with Susanna, hides behind the chair. Cherubino leaves that hiding place just in time, and jumps onto the chair while Susanna scrambles to cover him with a dress. When Basilio starts to gossip about Cherubino's obvious attraction to the Countess, the Count angrily leaps from his hiding place. Lifting the dress from the chair he finds Cherubino. The young man is only saved from punishment by the entrance of the peasants of the Count's estate, this entrance being a preemptive attempt by Figaro to commit the Count to a formal gesture symbolizing the promise of Susanna's entering into the marriage unsullied. The Count evades Figaro's plan by postponing the gesture. The Count says that he forgives Cherubino, but he dispatches him to Seville for army duty. Figaro gives Cherubino mocking advice about his new, harsh, military life from which women will be totally excluded (aria: Non pi andrai "No more gallivanting").[17] [edit] Act 2 A handsome room with an alcove, a dressing room on the left, a door in the background (leading to the servants' quarters) and a window at the side. The Countess laments her husband's infidelity. (aria: Porgi, amor, qualche ristoro "Grant, love, some comfort"). Susanna comes in to prepare the Countess for the day. She responds to the Countess's questions by telling her that the Count is not trying to "seduce" her, he is merely offering her a monetary contract in return for her affection. Figaro enters and explains his plan to distract the Count with anonymous letters warning him of adulterers. He has already sent one to the Count (via Basilio) that indicates the Countess has a rendezvous that evening of her own. They hope that the Count will be too busy looking for imaginary adulterers to interfere with Figaro's and Susanna's wedding. Figaro additionally advises the Countess to keep Cherubino around. She should dress him up as Susanna and lure the Count into an illicit rendezvous where he can be caught red-handed. Figaro leaves. Cherubino arrives, sent in by Figaro and eager to co-operate. Susanna urges him to sing the song he wrote for the Countess (aria: Voi che sapete che cosa amor "You ladies who know what love is, is it what I'm suffering from?"). After the song, the Countess, seeing Cherubino's military commission, notices that the Count was in such a hurry that he forgot to seal it with his signet ring (which was necessary to make it an official document). They proceed to

attire Cherubino in women's clothes (aria of Susanna: Venite, inginocchiatevi! "Come, kneel down before me"), and Susanna goes out to fetch a ribbon. While the Countess and Cherubino are waiting for Susanna to come back, they suddenly hear the Count arriving. Cherubino hides in the closet. The Count demands to be allowed into the room and the Countess reluctantly unlocks the door. The Count enters and hears a noise from the closet. He tries to open it, but it is locked. The Countess tells him it is only Susanna, trying on her wedding dress. The Count shouts for her to identify herself by her voice, but the Countess orders her to be silent. At this moment, Susanna re-enters unobserved, quickly realises what's going on, and hides behind a couch (Trio: Susanna, or via sortite! "Susanna, come out!"). Furious and suspicious, the Count leaves, with the Countess, in search of tools to force the closet door open. As they leave, he locks all the bedroom doors to prevent the intruder from escaping. Cherubino and Susanna emerge from their hiding places, and Cherubino escapes by jumping through the window into the garden. Susanna then takes his place in the closet, vowing to make the Count look foolish. (duet: Aprite, presto, aprite "Open the door, quickly!"). The Count and Countess return. The Countess desperately admits that Cherubino is hidden in the closet. The raging Count draws his sword, promising to kill Cherubino on the spot, but when the door is opened, they both find to their astonishment only Susanna. The Count demands an explanation; the Countess tells him it is a practical joke, to test his trust in her. Shamed by his jealousy, the Count begs for forgiveness. When the Count presses about the anonymous letter, Susanna and the Countess reveal that the letter was written by Figaro, and then delivered through Basilio. Figaro then arrives and tries to start the wedding festivities, but the Count berates him with questions about the anonymous note. Just as the Count is starting to run out of questions, Antonio the gardener arrives, complaining that a man has jumped out of the window and broken his flowerpots. The Count immediately realizes that the jumping fugitive was Cherubino, but Figaro claims it was he himself who jumped out the window, and fakes a foot-injury. Antonio brings forward a paper which, he says, was dropped by the escaping man. The Count orders Figaro to prove he was the jumper by identifying the paper (which is, in fact, Cherubino's appointment to the army). Figaro is able to do this because of the cunning teamwork of the two women. His victory is, however, short-lived; Marcellina, Bartolo, and Basilio enter, bringing charges against Figaro and demanding that he honor his contract to marry Marcellina. The Count happily postpones the wedding in order to investigate the charge. [edit] Act 3 A rich hall, with two thrones, prepared for the wedding ceremony. The Count mulls over the confusing situation. At the urging of the Countess, Susanna enters and gives a false promise to meet the Count later that night in the garden (duet: Crudel, perch finora "Cruel girl, why did you make me wait so long"). As Susanna leaves, the Count overhears her telling Figaro that he has already won the case. Realizing that he is being tricked (aria: Hai gi vinta la causa ... Vedr mentr'io sospiro "You've already won the case?" ... "Shall I, while sighing, see"), he resolves to make Figaro pay by forcing him to marry Marcellina. Figaro's trial follows, and the judgment is that Figaro must marry Marcellina. Figaro argues that he cannot get married without his parents' permission, and that he does not know who his parents are, because he was stolen from them when he was a baby. The ensuing discussion reveals that Figaro is Rafaello, the long-lost illegitimate son of Bartolo and Marcellina. A touching scene of reconciliation occurs. During the celebrations, Susanna enters with a payment to release Figaro from his debt to Marcellina. Seeing Figaro and Marcellina in celebration together, Susanna mistakenly believes that Figaro now prefers Marcellina over her. She has a tantrum and slaps Figaro's face. Figaro explains, and Susanna, realizing her mistake, joins the celebration. Bartolo, overcome with emotion, agrees to marry Marcellina that evening in a double wedding (sextet: Riconosci in questo amplesso una madre "Recognize a mother in this embrace"). All leave, and the Countess, alone, ponders the loss of her happiness (aria: Dove sono i bei momenti "Where are they, the beautiful moments"). Susanna enters and updates her regarding the plan to trap the Count. The Countess dictates a love letter for Susanna to give to the Count, which suggests that he meet her that night, "under the pines". The letter instructs the Count to return the pin which fastens the letter. (duet: Sull'aria...che soave zeffiretto "On the breeze What a gentle little Zephyr"). A chorus of young peasants, among them Cherubino disguised as a girl, arrives to serenade the Countess. The Count arrives with Antonio, and, discovering the page, is enraged. His anger is quickly dispelled by Barbarina (a peasant girl, Antonio's daughter), who publicly recalls that he had once offered to give her anything she wants, and asks for Cherubino's hand in marriage. Thoroughly embarrassed, the Count allows Cherubino to stay. The act closes with the double wedding, during the course of which Susanna delivers her letter to the Count. Figaro watches the Count prick his finger on the pin, and laughs, unaware that the love-note is from Susanna herself. As the curtain drops, the two newlywed couples rejoice. [edit] Act 4 The garden, with two pavilions. Night.

Following the directions in the letter, the Count has sent the pin back to Susanna, giving it to Barbarina. Unfortunately, Barbarina has lost it (aria: L'ho perduta, me meschina "I lost it, poor me"). Figaro and Marcellina see Barbarina, and Figaro asks her what she is doing. When he hears the pin is Susanna's, he is overcome with jealousy, especially as he recognises the pin to be the one that fastened the letter to the Count. Thinking that Susanna is meeting the Count behind his back, Figaro complains to his mother, and swears to be avenged on the Count and Susanna, and on all unfaithful wives. Marcellina urges caution, but Figaro will not listen. Figaro rushes off, and Marcellina resolves to inform Susanna of Figaro's intentions. Marcellina sings of how the wild beasts get along with each other, but rational humans can't (aria: Il capro e la capretta "The billy-goat and the she-goat"). (This aria and Basilio's ensuing aria are usually omitted from performances due to their relative unimportance, both musically and dramatically; however some recordings include them.) Actuated by jealousy, Figaro tells Bartolo and Basilio to come to his aid when he gives the signal. Basilio comments on Figaro's foolishness and claims he was once as frivoulous as Figaro was. He tells a tale of how he was given common sense by "Donna Flemma" and ever since he has been aware of the wiles of women (aria: In quegli anni "In youthful years"). They exit, leaving Figaro alone. Figaro muses on the inconstancy of women (aria: Aprite un po' quegli occhi "Open your eyes"). Susanna and the Countess arrive, dressed in each other's clothes. Marcellina is with them, having informed Susanna of Figaro's suspicions and plans. After they discuss the plan, Marcellina and the Countess leave, and Susanna teases Figaro by singing a love song to her beloved within Figaro's hearing (aria: Deh, vieni, non tardar "Oh come, don't delay"). Figaro is hiding behind a bush and, thinking the song is for the Count, becomes increasingly jealous. The Countess arrives in Susanna's dress. Cherubino shows up and starts teasing "Susanna" (really the Countess), endangering the plan. Fortunately, the Count gets rid of him by striking out in the dark. His punch actually ends up hitting Figaro, but the point is made and Cherubino runs off. The Count now begins making earnest love to "Susanna" (really the Countess), and gives her a jewelled ring. They go offstage together, where the Countess dodges him, hiding in the dark. Onstage, meanwhile, the real Susanna enters, wearing the Countess' clothes. Figaro mistakes her for the Countess, and starts to tell her of the Count's intentions, but he suddenly recognizes his bride in disguise. He plays along with the joke by pretending to be in love with "my lady", and inviting her to make love right then and there. Susanna, fooled, loses her temper and slaps him many times. Figaro finally lets on that he has recognized Susanna's voice, and they make peace, resolving to conclude the comedy together. The Count, unable to find "Susanna", enters frustrated. Figaro gets his attention by loudly declaring his love for "the Countess" (really Susanna). The enraged Count calls for his people and for weapons: his servant is seducing his wife. Bartolo, Basilio and Antonio enter with torches as, one by one, the Count drags out Cherubino, Barbarina, Marcellina and the "Countess" from behind the pavilion. All beg him to forgive Figaro and the "Countess", but he loudly refuses, repeating "no" at the top of his voice, until finally the real Countess re-enters and reveals her true identity. The Count, seeing the ring he had given her, realizes that the supposed Susanna he was trying to seduce, was actually his wife. Ashamed and remorseful, he kneels and pleads for forgiveness himself (Contessa, perdono "Countess, forgive me"). The Countess, more kind than he (Pi docile io sono "I am more kind"), forgives her husband and all are contented. The opera ends in a night-long celebration. The Marriage of Figaro is scored for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, and strings; the recitativi are accompanied by a keyboard instrument, usually a fortepiano or a harpsichord, often joined by a cello. The instrumentation of the recitativi is not given in the score, so it is up to the conductor and the performers. A typical performance usually lasts around 3 hours. [edit] Frequently omitted numbers Two arias from act 4 are usually omitted: one in which Marcellina regrets that people (unlike animals) abuse their mates (Il capro e la capretta), and one in which Don Basilio tells how he saved himself from several dangers in his youth, by using the skin of an ass for shelter and camouflage (In quegli anni). [edit] Musical style In spite of all the sorrow, anxiety, and anger the characters experience, only one number is in a minor key: Barbarina's brief aria L'ho perduta at the beginning of act 4, where she mourns the loss of the pin and worries about what her master will say when she fails to deliver it, is written in F minor. Other than this the entire opera is set in major keys. Mozart uses the sound of two horns playing together to represent cuckoldry, in the act 4 aria Aprite un po quelli'ochi. Verdi later used the same device in Ford's aria in Falstaff. An aria is a song or air. The word is used in particular to indicate formally constructed songs in opera. The socalled da capo aria of later baroque opera, oratorio and other vocal compositions, is an aria in which the first

section is repeated, usually with additional and varied ornamentation, after the first two sections. The diminutive arietta indicates a little aria, while arioso refers to a freer form of aria-like vocal writing.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- 1 ST Iternal PaperDocumento7 pagine1 ST Iternal PaperSIVA KRISHNA PRASAD ARJANessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Chord ProgressionDocumento2 pagineChord Progressionsenonais nissaroub100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Lesson 1: Understanding The Aerobics Exercise: College of Human KineticsDocumento7 pagineLesson 1: Understanding The Aerobics Exercise: College of Human KineticsCamille CarengNessuna valutazione finora

- Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys.: A MemoirDocumento3 pagineClothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys.: A MemoirJadson Junior0% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- SE125 ClassDocumento125 pagineSE125 ClassdanialsafianNessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Batman V Superman - The Red Capes Are Coming (Lex Luthor Theme) PDFDocumento2 pagineBatman V Superman - The Red Capes Are Coming (Lex Luthor Theme) PDFMenno0% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Manuale StoegerDocumento107 pagineManuale StoegerPaolo Marcello BattianteNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- xlr8 Carb CyclingDocumento67 paginexlr8 Carb CyclingH DrottsNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Man Who Shouted TeresaDocumento4 pagineThe Man Who Shouted Teresachien_truongNessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- 90 Day Bikini Home Workout Weeks 5 - 8Documento5 pagine90 Day Bikini Home Workout Weeks 5 - 8Breann EllingtonNessuna valutazione finora

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grazilaxx'S Guide: AncestryDocumento35 pagineGrazilaxx'S Guide: AncestryJoão BrumattiNessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- LQA StandardsDocumento4 pagineLQA StandardsSharad SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Samsung HT E6759w ZGDocumento106 pagineSamsung HT E6759w ZGUngureanu Stefan RaymondNessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- CIE IGCSE FLE PAST PAPER 0500 - w03 - QP - 2Documento8 pagineCIE IGCSE FLE PAST PAPER 0500 - w03 - QP - 2mwah5iveNessuna valutazione finora

- PARAMORE-Rose Color Boy Bass TabDocumento1 paginaPARAMORE-Rose Color Boy Bass TabGerardo Herrera-BenavidesNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Favorite Tactical Pistol Practice DrillsDocumento39 pagineFavorite Tactical Pistol Practice Drillspsypanop100% (1)

- What Did You Do YesterdayDocumento8 pagineWhat Did You Do YesterdayBuanaMutyaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Shatabdi Express (A Short Story)Documento10 pagineShatabdi Express (A Short Story)Paramjit SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- DIAGRAMAS de Bloques IphoneDocumento14 pagineDIAGRAMAS de Bloques Iphonetecno worksNessuna valutazione finora

- Format - Single Camera TechniqueDocumento2 pagineFormat - Single Camera Techniquemreeder11Nessuna valutazione finora

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Michael Learns To RockDocumento4 pagineMichael Learns To RockSaging Giri0% (1)

- Chapter 2Documento10 pagineChapter 2Abolade OluwaseyiNessuna valutazione finora

- About Nepal. "Tourism in Nepal"Documento40 pagineAbout Nepal. "Tourism in Nepal"Rammani KoiralaNessuna valutazione finora

- Crossword Puzzle - NumbersDocumento1 paginaCrossword Puzzle - NumbersVahid UzunlarNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

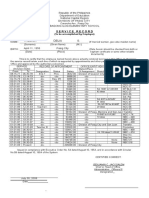

- Service RecordDocumento5 pagineService RecordCHARMINE GAY ROQUENessuna valutazione finora

- FIFA World Cup Winners List For General AwarenessDocumento3 pagineFIFA World Cup Winners List For General AwarenessKonda GopalNessuna valutazione finora

- Adiff - Clothing System Top ExtDocumento14 pagineAdiff - Clothing System Top ExtsoledadNessuna valutazione finora

- ASSASSIN'S CREED UNITY 100% Complete Save Game PCDocumento10 pagineASSASSIN'S CREED UNITY 100% Complete Save Game PCunitysavegame0% (6)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- RRR Rabbit Care Info 2021Documento7 pagineRRR Rabbit Care Info 2021api-534158176Nessuna valutazione finora

- ERLPhase USB Driver InstructionsDocumento9 pagineERLPhase USB Driver InstructionscacobecoNessuna valutazione finora

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)