Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

2007 The Social Epidemiologic Concept of Fundamental Cause

Caricato da

Samuel Andrés AriasDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

2007 The Social Epidemiologic Concept of Fundamental Cause

Caricato da

Samuel Andrés AriasCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Theor Med Bioeth (2007) 28:465485 DOI 10.

1007/s11017-007-9053-x

The social epidemiologic concept of fundamental cause

Andrew Ward

Published online: 13 March 2008 Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2008

Abstract The goal of research in social epidemiology is not simply conceptual clarication or theoretical understanding, but more importantly it is to contribute to, and enhance the health of populations (and so, too, the people who constitute those populations). Undoubtedly, understanding how various individual risk factors such as smoking and obesity affect the health of people does contribute to this goal. However, what is distinctive of much on-going work in social epidemiology is the view that analyses making use of individual-level variables is not enough. In the spirit of Durkheim and Weber, S. Leonard Syme makes this point by writing that just as bad water and food may be harmful to our health, unhealthful forces in our society may be detrimental to our capacity to make choices and to form opinions conducive to health and well-being. Advocates of upstream (distal) causes of adverse health outcomes propose to identify the most important of these unhealthful forces as the fundamental causes of adverse health outcomes. However, without a clear, theoretically precise and well-grounded understanding of the characteristics of fundamental causes, there is little hope in applying the statistical tools of the health sciences to hypotheses about fundamental causes, their outcomes, and policies intended to enhance the health of populations. This paper begins the process of characterizing the social epidemiological concept of fundamental cause in a theoretically respectable and robust way. Keywords Fundamental cause Social epidemiology Causality Necessary cause Sufcient cause Social-context variable

A. Ward (&) Health Policy and Management, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, 420 Delaware Street S.E, Minneapolis, MN 55455-0392, USA e-mail: ward0230@umn.edu

123

466

A. Ward

Introduction In the principal article of the recent book, Is Inequality Bad for Our Health?, Norman Daniels, Bruce Kennedy, and Ichiro Kawachi make the following claim: To act justly in health policy, we must have knowledge about the causal pathways through which socioeconomic (and other) inequalities work to produce differential health outcomes [1]. The causal pathways in which Daniels, Kennedy and Kawachi are most interested are not those that originate in the relatively proximate (downstream) risk behaviors or even access to care. Instead, they believe that it is only by looking much further upstream to socio-economic conditions, and examining the causal pathways that link them to health outcomes, that it is possible to affect just, lasting positive health outcomes ([1]. Also, see [2]). In that context, their claim echoes an earlier one by Bruce Link and Jo Phelan to which social epidemiologists often refer. This 1995 claim, made in the Journal of Health and Social Behavior, was: ... medical sociologists and social epidemiologists need to take as their task the identication and thorough consideration of social conditions that are what we term fundamental causes of diseases. We call them fundamental causes because, as we shall see, the health effects of causes of this sort cannot be eliminated by addressing the mechanisms that appear to link them to disease [3]. The fundamental causes with which Link and Phelan were (and still are) concerned include, but may not be limited to, the socioeconomic inequalities referred to by Daniels, Kennedy, and Kawachi. Still, what is common to both sets of claims is that truly efcacious, just health policies that aim to improve the health of populations, and reduce health disparities, must identify fundamental causes of health outcomes and, when those health outcomes are adverse, change the fundamental causes. Implicit in this claim is that while changes in non-fundamental causes may eliminate or mitigate specic adverse health outcomes, the elimination or equitable mitigation will be transitory. In some cases, new adverse health outcomes, or new non-fundamental, mediating (intervening) mechanisms, linking fundamental causes to adverse health outcomes, will emerge [36]. In other cases, the discovery or control of remaining non-fundamental mediating (intervening) mechanisms may be differentially distributed (e.g., on socio-economic status), thus creating (or perpetuating) health disparities [3, 7, 8]. Therefore, according to advocates of fundamental causes, creating just public health policy that will bring about a lasting elimination or equitable mitigation of adverse health outcomes requires both an understanding of what it means to be a fundamental cause, and an identication of those causes (if any) that are genuinely fundamental causes. Unfortunately, there is considerable vagueness and ambiguity attended to discussions of fundamental causes. Moreover, other than an inchoate conception of distal vs. proximate (or basic vs. surface) causes, there seems to be little agreement about the conceptual underpinnings of the concept. To that end, the objective of the

123

Social epidemiologic concept of fundamental cause

467

present paper is to characterize, in a theoretically careful, though robust way, the social epidemiological concept of fundamental cause.

Necessary, sufcient and component causes A good place to begin is with Kenneth Rothmans 1976 paper Causes (Also, see [9]). Early on, Rothman offers a general characterization of a cause that he intends to bridge the gap between metaphysical and epidemiological approaches to the conceptual framework for causes [10]. According to Rothman, a cause is an act or event or a state of nature which initiates or permits, alone or in conjunction with other causes, a sequence of events resulting in an effect.1 With this characterization in mind, let us consider a simple causal diagram [12]. Suppose that we have two events,2 X and Y, causally related to one another in the sense that X is the cause of Y. It is possible to represent, graphically (in a manner suggestive of path analysis), this relationship between X and Y as: X!Y In this representation, the direction of the arrow indicates the direction of causality (cause to effect). The use of this graphical representation also reects the assumption that the causal relation is asymmetric (X causes Y, but Y is not a cause of X). There are several ways to taxonomize this relationship, but a traditional taxonomy of the relations captured by the causal use of the ? is to say that X causes Y in one or more of the following ways: (1) (2) (3) (4) X X X X is is is is a necessary cause of Y sufcient cause of Y a necessary and sufcient cause of Y a neither a necessary nor a sufcient cause of Y (See [912, 1420]).

Sometimes the claim is made that this taxonomy is sufcient only for cases in which the relationship between X and Y is deterministic. Equating non-deterministic relationships with probabilistic relationships, the claim is that when the relationship between X and Y is probabilistic, the taxonomy is, at best, inadequate. However, while it is not without its critics [21, 22], there is a standard way around this objection. We can accept the claim of Daniel Hausman and James Woodward

1 Rothman [10]. Rothman and Greenland [11], offer a somewhat more restrictive characterization of a cause as an antecedent event, condition, or characteristic that was necessary for the occurrence of the disease at the moment it occurred, given that other conditions are xed. (emphasis added). 2

There is a voluminous philosophical literature devoted to the logical and ontological characterization of events. A succinct denition, accepted (to a greater or lesser extent) by many writers, is due to Jaegwon Kim. According to Kim, an event is a concrete object (or n-tuple objects) exemplifying a property (or n-adic relation) at a time. In this sense of event, events include states, conditions, and the like, and not only events narrowly conceived as involving changes. [13].

123

468

A. Ward

that probabilistic causation is deterministic causation of probabilities.3 What this means is that X is a probabilistic cause of Y if and only if X is a deterministic cause of the chance of Y, ch(Y), where this is identied with the objective probability of Y [23]. In this case, we can say that if X is a necessary cause of Y, then whenever X does not occur, either Y does not occur or the probability of Y occurring (i.e., the chance of Y, ch(Y)), in the language of Hausman and Woodward) is less than it would have been if X had occurred. In contrast, if X is a sufcient cause of Y, then whenever X occurs, either Y occurs or the probability of Y occurring (i.e., the chance of Y, ch(Y), in the language of Hausman and Woodward) is greater than it would have been if X had not occurred (See [10, 15]). If X is both a necessary and sufcient cause of Y, then we have a conjunction of sufcient cause and necessary cause. That is to say, whenever X occurs, either Y occurs or the probability of Y occurring is greater than if X had not occurred, and whenever X does not occur, either Y does not occur or the probability of Y occurring is less than it would have been if X had occurred. Finally, if X is neither a necessary nor a sufcient cause of Y, then whenever X occurs there is no guarantee either that Y will occur, or that the probability of the occurrence of Y will be greater than if X had not occurred. Moreover, if X is neither a necessary nor a sufcient cause of Y, then whenever X does not occur, there is no guarantee either that Y will not occur, or that the probability of the occurrence of Y will be less than if X had occurred. Within the context of this taxonomy of causes, it is important to recognize that neither X nor Y may be unitary; instead, X may be a constellation (complex) of causes, and Y may be a constellation (complex) of effects [9]. Also, see [2628]). Using language introduced by Rothman, we may call the constituent elements of a complex of causes, component causes, and we may call the constituent elements of a complex of effects, component effects ([9]. Also, see [29]). In the case of the component causes, for every specic causal complex of which the component cause is a proper subset of the set of component causes constituting the causal complex, that component cause will be either a necessary cause, or neither a necessary nor a sufcient cause. For example, suppose that A is a non-redundant component cause of a causal complex C (i.e., no other constituent elements of C, different from A, are by themselves sufcient to case the effect Y), where C is a sufcient but not necessary cause of some effect Y, and A is not, by itself, a sufcient cause of Y. In this case, following J.L. Mackie, we can say that A is an insufcient but necessary (INUS) cause of Y [30, 31]. Notice that in this case, there are two senses of necessity that must be kept separate. Since A is a non-redundant component cause of the causal complex C, which is a sufcient but not necessary cause of Y, then A is necessary in the sense of being a non-redundant component of C. If one eliminated A from the causal complex C, C would no longer be a sufcient but not necessary cause of Y. However, suppose that there are two causal complexes, C and

3 Hausman and Woodward [23]. Also, see Hausman [24] and Karhausen [16]. This is not the only way to handle cases of probabilistic causation. Hitchcock [25] provides a summary of approaches making use of probability spaces and partitions of probability spaces.

123

Social epidemiologic concept of fundamental cause

469

C0 , both of which are sufcient but not necessary causes of Y. Further, suppose that none of the constituent elements of C are constituent elements of C0 , and none of the constituent elements of C0 are constituent elements of C. In this case, while A remains necessary in the sense of being a non-redundant component cause of C, it is not necessary in the sense of being an irreplaceable cause of Y. Finally, a component cause, A, of a specic causal complex C is neither a sufcient nor a necessary component cause of an effect, Y, just in case there is some other causal complex, C0 , which is a sufcient cause of Y, and to which the component cause, A, does not belong. We can use this taxonomy and vocabulary to classify some simple examples. As Rothman writes, under ordinary conditions (ceteris paribus), the possession of a vermiform appendix is necessary for appendicitis, and infection with the tubercle bacillus is a necessary cause for tuberculosis [10]. In other words, under ordinary conditions (what, following Mackie [31]. We can refer to as the causal eld of reference) appendicitis cannot occur if there is no vermiform appendix, and tuberculosis cannot occur if the tubercle bacillus is not present (See [27, 32, 15]). A standard bar examination question about responsibility provides a good example of a sufcient, but not necessary cause: If a person is pushed from the top of a tall building and, while falling, is shot, which of the events is the cause of the persons death? In the context of the necessarysufcient taxonomy, we can say that the problem for assigning responsibility is that while both events (i.e., being pushed from the top of a tall building and being shot while falling) are sufcient causes (under ordinary circumstances, both events will inevitably result in the persons death), neither is a necessary cause. The person will die from the fall if not shot, and will die from the shot if not from the fall. Again, returning to Rothman, another example of a sufcient cause is that under ordinary circumstances the inheritance of the PKU gene and phenylalanine in a diet are, together, a sufcient cause for the occurrence of mental retardation [10]. What is signicant about Rothmans example is that while neither inheritance of the PKU gene nor phenylalanine in a diet are, by themselves, sufcient causes of mental retardation, they are both causal components of a causal complex that is itself a sufcient cause, under ordinary circumstances, for mental retardation. The case of a cause that is a necessary and sufcient cause for an effect is more difcult. A simple example that is sometimes given is that, under ordinary circumstances, heat, air (O2) and fuel are singularly necessary and jointly sufcient for re. Thus, if we think of the component causes heat, air and fuel as constituting the causal complex C, then we can then say that, under ordinary circumstances, C is both a necessary and sufcient cause for re. In the sciences (social and natural), assertions of causal relations are often assertions of necessary causal relations (See [33, 17]). To understand this focus on necessary causes, consider the example of the claim that, under ordinary circumstances (ceteris paribus; relative to the causal eld of reference), smoking causes lung cancer. Here smoking is the cause (X), and lung cancer is the effect (Y). Even ignoring for a moment that smoking is much too broad a characterization of the event serving as the cause in the causal relationship (e.g., there are various kinds of smoking), it relatively easy to recognize that is not the case either

123

470

A. Ward

that smoking always causes lung cancer, or that smoking always results in an increased probability of lung cancer. No matter what the etiological time-period is (where the etiological time-period is the time-period covered by the causal relationship), there are cases in which either there are instances of smoking did not cause lung cancer, or there are instances of smoking that did not increase the probability of lung cancer.4 Thus, because it is not the case either that the occurrence of lung cancer always follows the occurrence of smoking, or that the probability of lung cancer when smoking occurs is always greater than it would have been if smoking had not occurred, it follows that smoking is not a sufcient cause of lung cancer [14, 35]. At most, we can say that the average incidence rate of lung cancer, over a specied etiological time-period, in a specic population of people who smoke, is greater than the average incidence rate of lung cancer, over a specied etiological time-period, in another specic population of people who do not smoke. Thus, the connection between (X)smokingand (Y)lung cancer is, in this case, a contingent generalization based on a specic selection of parameters, and so indicates the importance of precisely specifying the target population (as well as specifying the causal eld of reference). If we choose the target populations in a different way, it is quite possible that we will end up without this difference in average incidence of lung cancer (e.g., if we retrospectively choose the population of people who never develop lung cancer but who nevertheless smoke) (See [14]). Equally importantly though, even if the concept of cause is given this populationlevel probabilistic characterization in terms of average incidence (incidence proportions), no nite number of observations are ever sufcient to support the claim that an event is a sufcient cause for the occurrence of another event. Recall that an event X is a sufcient cause for an event Y only if whenever X occurs, either Y occurs or the probability of Y occurring is greater than if X had not occurred. It is the modality of whenever that creates the problem. No nite number of observations is sufcient to justify the claim that whenever X occurs, Y occurs. It is this (a version of the problem of inductive inferences rst made famous by David Hume) and related problems that led to Karl Poppers claim that falsication (instead of conrmation) is at the center of all genuine scientic explanations (See [36]). In other words, Popper claimed that rather than attempting to justify (conrm) claims about an event being a sufcient cause for another event, the correct approach is to attempt to refute scientic hypotheses about causal connections [36]. Only the falsity of a theory, writes Popper, can be inferred from empirical evidence, and this inference is a purely deductive one [37]. Thus, in the smoking case, once we have a precisely formulated hypothesis (including a specication of the ordinary conditions as well as the etiological time-period and the target population) about the causal relationship of smoking to lung cancer, we should

4 See Kelsey et al. [34], who characterize smoking as a risk factor for (as opposed to a cause of) lung cancer precisely because some lung cancer occurs in nonsmokers, and most smokers do not develop lung cancer. Other writers claim that risk factors are causes. For example, Link and Phelan [4], write that social conditions expose people to risk factors, and those risk factors cause disease, thereby producing patterns of disease in populations.

123

Social epidemiologic concept of fundamental cause

471

attempt to nd refutations of the relationship by nding instances of smokers who do not have lung cancer. Since we can do this (at least with a sufciently large extensional denition of smoking), then we know that smoking is not, for at least some characterizations of the hypothetical connection between smoking and lung cancer, a sufcient condition for lung cancer. These, and related problems associated with justifying (conrming) claims about sufcient causes, lead to a refocus on examining causal conditions as necessary causal conditions. In the case of the earlier example of infection with the tubercle bacillus as a necessary cause for tuberculosis, the idea, couched once again at the population level, is that in the case of people who have both the tubercle bacillus and tuberculosis: If they had not acquired the tubercle bacillus, then, all other things being equal (ceteris paribus; relative to the causal eld of reference), they would not have tuberculosis, or the probability of their having tuberculosis would be less than if they had never acquired the bacillus. In the case of smoking as a necessary cause of lung cancer, the idea, couched once again at the population level, is that in the case of people who have lung cancer and have smoked: Had they not smoked, then, all other things being equal (ceteris paribus; relative to the causal eld of reference), they would not have lung cancer, or the probability of their having lung cancer is less than if they had smoked. The example of smoking and lung cancer, perhaps more clearly than the example of the tubercle bacillus and tuberculosis, demonstrates the importance of precisely specifying the etiological time-period, the target population, the cause, the effect, and the causal eld of reference. Suppose that we change the causal eld of reference so that the smokers about whom we make the claim live in an environment that sufces, on its own without the people smoking, to cause lung cancer. For instance, imagine that the people live in an environment in which there is a high concentration of airborne asbestos particles. In this case (more specically, for the people living in this environment), smoking is not a necessary cause for lung cancer (See [38, 39]). Alternatively, suppose that we change the characterization of the effect to include only those types of lung cancer not physically (biologically) linked to smoking. Given this change in the characterization of the effect, smoking is not a necessary cause of lung cancer qua lung cancer as narrowly specied. Finally, if the lung cancer-effect, the background conditions, the cause (e.g., the specic type of smoking) and target population are chosen in the right way (with the proper precision), then smoking will be both a necessary and a sufcient cause for lung cancer. In this case, the smoking (cause)lung cancer (effect) case begins to look much more like the tubercle bacillustuberculosis case where, under ordinary circumstances, the tubercle bacillus is both a necessary and sufcient condition for tuberculosis. The upshot is that all claims about necessary causes (as well as about other kinds of causes in the taxonomy) occur in the context of many assumptions. Without making these assumptions (e.g., assumptions about the target population, the nature of the examined effects) explicit, it is impossible to

123

472

A. Ward

taxonomize a cause, and it is impossible to determine the warrant (good or bad) of a causal claim [40].

Fundamental causes With the comments in Sects. Introduction and Necessary, sufcient and component causes as background, we can better understand the concept of fundamental cause that recent social epidemiologists5 use in their analyses. As suggested by the quotation from Link and Phelan in Sect. Introduction [3], fundamental causes are not just any kinds of causes. Fundamental causes, as conceived by Link and Phelan, are distal causes of health outcomes relative to the more proximate risk factors commonly claimed to be the causes (typically adverse) of health outcomes (e.g., health behaviors such as smoking). Moreover, while risk factors may change over times and populations, advocates of fundamental causes claim that such causes maintain an enduring relationship to the health outcomes with which they are causally associated [3, 4143]. An important caveat in this characterization, often glossed over, concerns the character of the health outcomes. Although the earlier example about smoking and lung cancer may have suggested a relatively narrow characterization of the health outcome, this is not, typically, what advocates of fundamental causes intend. Instead, following Link and Phelan, since a single cause (or a single collection of component causes that together form a causal complex) can affect multiple health outcomes, then, properly speaking, we should understand the Y in the causal diagram, X ? Y, as a place holder for a variety of different values and not one specic value.6 Using language borrowed from James Woodward, we can say that claims of the form X is a fundamental cause of Y are type-causal claims ([39]. Also, see [23]). Thus, we need to understand properly the claim that fundamental causes maintain an enduring (persistent) relationship to the health outcomes with which they are causally associated. It is really the claim that the causal link between a fundamental cause and a collection of a variety of specic health outcomes endures even through changes either in the mechanisms or in the [specic] outcomes [of a certain type] ([3]. Also, see [2]). As Karen Lutfey and Jeremy Freese write, in assertions of the form X is a fundamental cause of Y, Y must be multiply realizable, in the sense that there are many different ways in which Y can occur [5]. In this respect, Y functions as a type-level variable; a variable that can be realized by a variety of different, more specic health outcomes. For example, consider the claim that lower socio-economic status is related to mortality from each of the broad categories of chronic diseases, communicable diseases, and injuries ... and from each of the 14 major causes of death in the International Classication of Diseases [44]. In the

5

Though see House [41], who traces the idea back as far as the 1843 work of the German physician and pathologist, Rudolf Virchow. Link and Phelan [3]. This captures the claim of Lutfey and Freese [5], that the effect of a fundamental cause must be multiply realizable, in the sense that there are many ways for the effect of interest to occur.

123

Social epidemiologic concept of fundamental cause

473

context of an assertion of the form socio-economic status is a fundamental cause of mortality, we can say that mortality is a type-level description of an effect that is realized multiply in the various kinds of adverse health outcomes including the 14 major causes of death in the International Classication of Diseases. The upshot is that if X is a fundamental cause of Y, then the causal relationship between X and a variety of specic instances of Y persist even if there are changes in the mediating factors between X and one or more of the specic instances of Y, or the specic instances of Y change [2, 4]. Moreover, not only is the effect of a fundamental cause multiply realizable, so too is the fundamental cause itself [5]. To vary the point made above in the quotation from Lutfey and Freese, X (the fundamental cause) must be multiply realizable, in the sense that there are many different ways in which X can occur. This can occur in at least two different ways. First, suppose that the fundamental cause is a specic aspect of socio-economic status, say, poverty level. If we then make the claim that poverty status is a fundamental cause of mortality, we are not saying that a specic persons poverty status is the cause of his or her mortality. Instead, what we are claiming is that, relative to a causal eld of reference, there is a necessary connection between the various events that fall under the type-level description poverty status, and the variety of different health outcomes that fall under the type-level description mortality. Second, suppose that we claim that socio-economic status is a fundamental cause of poverty status. Since socioeconomic status is a composite measure that typically incorporates economic status, measured by income; social status, measured by income; and work status, measured by occupation [45], it follows that poverty status is a type-level description under which fall various events and (sub-) level types of events. Thus, fundamental cause claims are type-causal claims in that both the descriptions of the fundamental causes as well as the descriptions of the effects of fundamental causes are type-level descriptions. One should not underestimate the importance of understanding claims about fundamental causes as type-causal claims (in the sense identied above) rather than as token-causal claims about narrowly individuated, particular events. Typically, social epidemiologists center their attention on adverse health outcomes qua collections of specic ailments [4]. Within this collection, there may be a variety of more specic health outcomes, such as lung cancer, diabetes and coronary heart disease, all of which collaborate, in one way or another, to warrant claims about the occurrence of the adverse health outcome effect. For example, in the 1996 paper The Effects of Poverty, Race, and Family Structure on U.S. Childrens Health: Data from the NHIS, 1978 through 1980 and 1989 through 1991, Laura Montgomery et al. [46] use National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data to investigate possible causes of adverse health outcomes (poor or fair health) as determined by the guardian-reported health status of children. The dependent variable in their analyses captures, collectively, one or more specic instances of health states that, cumulatively, lead the guardians to report children as having either fair or poor health. Put a bit differently, the dependent variable, Y, in the analysis is a type-level variable that captures specic instances of adverse health states and determined by the guardians of children. In this example, changing the

123

474

A. Ward

intermediate causes that connect fundamental causes to the collection of events that fall under a specic type-level effect may result in a decrease or elimination of specic instances of health states that contributed to the guardians reports of poor or fair health. However, according to advocates of fundamental causes, unless one eliminates the fundamental causes, one or more instances of the type-level effect will remain, or new events of that type will emerge, or the discovery (or control) of remaining non-fundamental mediating (intervening) mechanisms may be differentially distributed [2, 3, 5]. The point about understanding fundamental cause claims as type-causal claims is not a trivial one. In discussions of causation, causality and causal relations, writers (especially philosophically oriented writers) often draw a distinction between tokencausation (singular causation) and type-causation (general causation) (See [47, 25]). Referring back to the simple case of X ? Y, where X is the cause and Y is the effect, advocates of token-causation (See [38]). claim that X and Y are tokens (particular instances) of types of events. For example, X might be a particular behavior of an individual (e.g., the episode of smoking a cigarette at a particular time and place) while Y might be a particular health state (e.g., the episode of having a particular kind of cancer at a particular time and place). In contrast, advocates of type-causation claim that X and Y are types of events (which may or may not have specic tokens in the actual world). Typically, examples such as smoking causes cancer either count as genuine instances of type-causation or, as suggested earlier, as generalizations based on the distribution of specic tokens of smoking and cancer (particular people smoking and particular instances of cancer in persons) in a specied population relative to a causal eld of reference. Ellery Eells is an example of someone who claims that smoking cases cancer is a genuine instance of type-causation. He writes: The surgeon general says that smoking is a positive causal factor for lung cancer. This, of course, is a type-level causal claim, about the properties of being a smoker and of developing lung cancer. And it is consistent with various pertinent possibilities regarding token events, and the token causal relations between them [35]. It is for this reason that type-causation is sometimes called property causation [35]. One of the problems with countenancing this analysis of type-causation is that the introduction of properties distinct from their instantiation in specic events raises complex issues of ontology that have no simple, or generally agreed upon resolution. Thus, for present purposes, it sufces to note that, within social epidemiology as well as health services research, advocates of fundamental causes are not directly interested in the question of whether we should, or need to distinguish type-causation and token-causation as two distinct kinds of causation. Instead, as the examples above demonstrate, they are interested in cases where causes are collections of more specic causes (i.e., events or (sub-) types of events), and effects are collections of more specic outcomes (i.e., events or (sub-) types of events). Whether or not these more specic causes and outcomes (collected under the type-level descriptions of causes and effects) can always be understood as

123

Social epidemiologic concept of fundamental cause

475

collections of event tokes, and casual relations as relations obtaining between event tokens, is not generally a topic of interest amongst social epidemiologists. For this reason, I will say, generally, that a claim such as X causes Y is, within a social epidemiologic framework, a claim to the effect that changing the value of X, located in one or more specic events or (sub-) type of events that fall under the type-level description X, will change the value of Y located in one or more specic events or (sub-) type of events7 that fall under the type-level description Y. Just how narrowly specied and particularized these more specic events or (sub-) type of events are, is a pragmatic question determined by the nature of the research and the interest of those conducting the research. This leaves open the possibility that claims such as X causes Y could all be analyzed into claims that changing the value of X in particular, spatiotemporally located individuals will change the value of Y located in particular individuals [39], without requiring that all useful analyses must take this form. Given this characterization of the role of type-level descriptions and the pragmatic nature of the token-type distinction, there is no particular problem with providing operational denitions of the relevant concepts and, based on those operational denitions, constructing conceptual models. The operational denitions, in effect, place parameters on which specic events or (sub-) types of events fall under the type-level descriptions of the causes and effects in claims about fundamental causes [47]. Indeed, in this context it is useful to recall a remark from Max Webers The Theory of Social and Economic Organization. According to Weber, in all cases, rational or irrational, sociological analysis both abstracts from reality and at the same time helps us to understand it, in that it shows with what degree of approximation a concrete historical phenomenon can be subsumed under one or more ... concepts [49]. Using the above remarks as a general framework, we can make the following assertion: X (which is an element of a causal complex) is, relative to a causal eld of reference, a fundamental cause of Y only if: (i) Changing the value of X, instantiated in one or more specic events or (sub-) type of events is, relative to the causal eld of reference, a necessary cause of changing the value of Y instantiated in one or more specic events or (sub-) type of events. (ii) There is no different description of the instantiations of X such that, relative to that description and the causal eld of reference in (i), changing the value of X is a necessary cause of changing the value of Y identied in (i). Recent social epidemiologists, in the broadly Western cultural tradition, add a further qualication to (ii). They claim that the necessary causes identied by X are specic social conditions (e.g., socio-economic conditions). Put a bit differently, and using broadly Weberian language, they claim that it is necessary to subsume the descriptions of the events or (sub-) type of events that instantiate X under specic socio-economic concepts. The point of qualifying condition (ii) in this way is to

Instead of sub-types of events, one might instead make use of complex events. See Ehring [48].

123

476

A. Ward

eliminate claims that a so-called reductionist (or eliminativist) account is a better account of the necessary causal relationship (See [3], [42]). For example, sometimes people claim that explanations in which only the vocabulary of individual characteristics (e.g., a person being a smoker) is used are better explanations that those in which different, non-individualistic vocabularies are used (e.g., measurements of socio-economic status which indicate particular structural positions within society [50]). If one accepts such claims, and the implicit reductionism or eliminativism entailed by such claims, then socio-economic status (SES) qua SES is not a fundamental cause of adverse health outcomes of a particular kind. Instead, it is the events, or (sub-) type of events described in the vocabulary of individual characteristics that are the fundamental causes of adverse health outcomes of a particular kind. It is, though, precisely at this point that advocates of social conditions as fundamental causes make their counter-claim. Social epidemiologists agree that while there may be no xed rule on what types of variables there are, nevertheless it is important to distinguish at least two different types: social-context variables and individual-level variables.8 According to advocates of social conditions as fundamental causes, social conditions (i.e., events or (sub-) types of events described using the vocabulary of social-context properties or complexes of socialcontext properties) are necessary causes of some events or (sub-) types of events grouped together under the type-level description of the effect. Moreover, no different description of those social conditions (e.g., individual-level descriptions) captures both the necessary causal relationship and the desired theoretical generality (See [5, 52]). In other words, social epidemiologists who advocate fundamental causes believe that the necessary causes (i.e., the X in X ? Y, where X ? Y indicates the presence of a fundamental cause) have a very specic characteristic; viz., the causes are social-context events or (sub-) types of events that function as necessary causes of the types of health outcomes of interest [53]. As Link and Phelan write, social conditions have been, are, and will continue to be irreducible determinants of health outcomes and thereby deserve their appellation of fundamental causes of disease and death [52]. Framing the idea of fundamental cause in this way avoids having to focus on the difference between proximate and (relatively more) distal causes as the distinguishing characteristic of fundamental causes. At best, such a distinction is only a relative one. For any causal relationship in which X is a cause of Y, there is always (unless there are nal causes) going to be a cause for X, X0 , making X a more proximate cause of Y relative to X0 , and X0 a more distal cause, relative to X, of Y. To suppose that this is not the case is tantamount to the claim that there are uncaused causes. Thus, unless one wants to adopt an instrumental view of causal claims, characterizing fundamental causes in terms of proximate vs. distal causes (See [5]) is not helpful since such characterizations are always relative

8 See Moftt [51]. Moftt has a related, albeit somewhat different taxonomy of variable types. Moftt mentions four types that have been used in a number of different applications: environmental or ecological variables, demographic group variables, twin and sibling relations, and natural experiments.

123

Social epidemiologic concept of fundamental cause

477

characterizations.9 The characterization of fundamental cause in terms of necessary causes (where the relevant events or (sub-) type of events are described in social-context terms) avoids this issue. Although the generative mechanisms through which fundamental causes are able to inuence the outcome of interest may change (i.e., even though the mediator variables may change) [54], as long as the fundamental causes remain, the possibility of an occurrence of the (adverse) outcome will persist precisely because fundamental causes are necessary causes. In addition, by explicitly identifying fundamental causes as social-context events or (sub-) types of events, the social epidemiological conception of fundamental cause intentionally and self-consciously eschews the individualization of epidemiology [53]. At the same time, we must be very careful with this distinction. Too often writers who want to distinguish fundamental causes from other, more supercial causes of adverse health outcomes, refer to social structures as the causes of adverse health outcomes without being precise about the meaning of social structure. Thus, at the very least, we must exercise caution in distinguishing between individuallevel variables, social-context variables, and structural variables (See [55, 56]). Individual-level variables refer to individual physiological and psychological factors [57]. as well as individual behaviors, such as an individuals smoking or an individuals drinking [58]. Social-context variables refer to events or (sub-) types of events in which individuals have characteristics that emerge and are present only in social situations. The poverty status of an individual is a traditional example of a social-context variable (See [59]) because it is presupposes a context of people interacting with one another and the establishment of social norms [50]. Finally, structural variables, sometimes called ecological variables, refer to characteristics of groups (analogous to social facts in the older, Durkheimian language) and either not at all, or only derivatively, to the individuals composing the groups. For example, population density is a structural variable that does not refer to any specic characteristic or set of characteristics of the individuals constituting the population (See [60, 61]). In contrast, age distribution measured by proportion of the female population aged 024 years represents, derivatively,10 individual level properties [56, 51]. All three kinds of variables are important and, as Barbara Wells and John Horm write, an ecological approach that uses groups, rather than individuals, as the unit of study is thought to be an important complement to measures of health attributes. Such an approach may help capture the context of communities, cultures, and other groupings ([62]. See also [63]). Failure to sort these different kinds of variables out leads to traditional kinds of fallacies. For example, to suppose that one

This claim does not entail that the distal vs. proximate distinction is not sometimes a useful one. As Professor Bryan Dowd, Health Policy and Management, University of Minnesota, rightly notes, causal diagrams such as Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) capture the distinction and use it. However, this is consistent with the claim that the distinction is not useful for capturing the meaning of fundamental cause.

10 The group-level property represents the individual-level property in a derivatively in that while individuals do have ages (as opposed to population densityindividuals do not have density in the relevant sense), the age distribution is a characteristic of the group.

123

478

A. Ward

can, from individual-level variables alone, determine the character and context of group-level variables is an instance of the atomistic fallacy. At the other extreme, to suppose that one can determine, from group-level variables alone, the character and content of individual-level variables is an instance of the ecological fallacy ([64]. See also [65, 63]). Furthermore, once these various levels are distinguished, and reductionism abandoned, then two other kinds of fallacies emerge. The psychologistic fallacy comes from assuming that individual-level outcomes can be explained exclusively by individual-level characteristics, while the sociologistic fallacy comes from ignoring the role of individual-level factors in a study of groups [66]. Of the three kinds of variables, social-context variables are the ones that seem to straddle what is otherwise a symptom of the agency-structure dichotomy, and the attendant distinction between micro-sociology and macro-sociology.11 Whereas individual-level variables are agency variables, and group-level variables are (social) structural variables, social-context variables incorporate elements from both. On the one hand, individuals realize social-context characteristics such as poverty status. In this respect, social-context variables have characteristics of individual-level variables. On the other hand, the realization of social-context variables occurs only in social contexts, and, in this respect, social-context variables have characteristics of group-level variables. Thus, David Betson and Jennifer Warlick, after noting that the adjective poor is used to describe an individual characteristic, continue by writing that it is a condition below average or could be viewed as unacceptable [68]. thereby recognizing the relative (social-context) character of poverty [68]. Similarly, Catherine Ross and John Mirowsky note that social causation proponents often claim that individual employment status is a social cause of health status [69]. Like poverty, employment status is a socialcontext variable because employment status is relative to specic social structures and the norms that exist in those social structures. Indeed, social-context variables constitute the kind of bridge between agents (individuals) and social structures (groups) one nds in the work of Anthony Giddens (See [61]). Moreover, because the variables are instantiated in (and by) individuals, they permit, methodologically, an analysis of fundamental causes that avoids, at least in its initial formulation, problems associated with multi-level analyses.

Possible problems One might object here that treating fundamental causes as necessary causes has its own problems. The rst problem seems to be that the claim that X is a fundamental cause of Y only if X is a necessary cause of Y results in characterizing too many causes as fundamental causes. Recall Rothmans example of the tubercle bacillus as a necessary cause for tuberculosis. If X is a fundamental cause of Y only if X is a

11 Giddens [61] and Collins [67]. As Giddens [61] writes, if interpretative sociologies are founded, as it were, upon an imperialism of the subject, functionalism and structuralism propose an imperialism of the social object. Like Giddens, I reject this dualism (and so too multi-level analysis that depend exclusively on the distinction), and want to recognize that there are social practices ordered across space and time.

123

Social epidemiologic concept of fundamental cause

479

necessary cause of Y, then it seems to follow that the tubercle bacillus (more precisely, the set of events or (sub-) types of events that fall under the type-level description tubercle bacillus) is a fundamental cause of tuberculosis. This, though, misses the logical character of the claim that X is a fundamental cause of Y only if X is a necessary cause of Y. The claim amounts only to saying that all instances of fundamental causes are also instances of necessary causes without, at the same time, claiming that all instances of necessary causes are instances of fundamental causes. In order for X ? Y to be an instance of fundamental causation in the relevant social epidemiological sense, two criteria must be satised. First, X must be a necessary cause of Y in the sense explicated above (Sect. Fundamental causes). Second, the necessary cause of Y, X, must be one or more social-context events (e.g., the poverty status of a person) or one or more (sub-) types of social-context events. It is only when both criteria are satised that we have a genuine instance of fundamental causation in the social epidemiological sense. Of course, precising the denition of fundamental cause in this way does not preclude an analogous use of the concept when the rst criterion is satised (i.e., the cause is a necessary cause) but the second criterion is relaxed (or changed). Nothing in the way that social epidemiologists use the concept of fundamental cause precludes the existence of analogous kinds of fundamental causation in which the causes are something other than events or (sub-) types of events described in the vocabulary of social-context properties.12 For example, Link and Phelan write that because of their pervasive effects and relation to resources such as money and power, characteristics such as race/ethnicity and gender should be considered as potential fundamental causes of disease as well ([3]. Also, see [41, 71]). Examples such as these are provocative precisely because of the debate about whether race/ ethnicity and gender are, in an important sense, socially constructed (and so must be described using the vocabulary of social-context properties). If they are characteristics that emerge and have meaning only in social contexts, then they are socialcontext variables and one can treat them straightforwardly as candidates for fundamental causes. However, even if one denies that they are social-context variables, to the degree that they have the effects Link and Phelan attribute to them, there does not seem any principled reason to exclude them as analogues to the social epidemiological conception of fundamental cause. Instead, the appropriate response to the example of the tubercle bacillus suggests the appropriate response to the case of race/ethnicity and gender variables. In particular, the appropriate response is that social epidemiologists qua social epidemiologists are interested in a specic level of explanationviz., a level in which claims about fundamental causes refer to events or (sub-) types of events described in the vocabulary of social-context properties. Of course, even in the tubercle bacillustuberculosis case, social epidemiologists may be interested in whether there are social conditions that serve as the fundamental causes of the tubercle bacillus, and so may be interested in tuberculosis as a specic kind of adverse health event type. What is important, is that for the social

12 See Gottfredson [70], for an argument that the general intelligence factor, g (a paradigmatic individual-level property) has all the requisite properties of a fundamental cause.

123

480

A. Ward

epidemiologist interested in fundamental cases, it is a mistake to collapse all causes into individual-level causes. Even though individualistic epidemiology has been the dominant tradition in the United States and Britain since the turn of the century,13 focusing exclusively on the individual level without taking group-level factors into account is, as Ana Diez-Roux writes, to commit the psychologistic or individualistic fallacy [53]. The moral we should draw from Diez-Rouxs remark is that a fully general account of fundamental causes of adverse health outcomes must incorporate the social epidemiological concept of fundamental cause as well as analogous conceptions of fundamental cause in which the causes are not all events or (sub-) types of events described using the vocabulary of social-context properties (See [55, 74]). A virtue of focusing on an approach to fundamental causes that avoids the exhaustive dualism of individual and group-level characterizations by using social-context variables is that it avoids both ecological and psychologistic or individualistic fallacies while acknowledging the possibility of multiple approaches to questions of causality (Duncan et al. [75]). The remarks in the preceding two paragraphs lead to a second potential problem in which we have a chain of causes and effects, where multiple causes in the chain are necessary causes. For example, suppose that we have the following: X ! X0 ! Y Moreover, suppose that X0 is a necessary cause of Y, and that X is a necessary cause of X0 . Can we still say that X0 is a fundamental cause of Y? The answer is Yes. We can say that X0 is a fundamental cause of C, though if both X and X0 are constituted by events or (sub-) types of events described in the vocabulary of socialcontext properties, we cannot (rightly) say that X0 is, in the social epidemiological sense, the fundamental cause of Y. Instead, since X0 is a fundamental cause of Y and X is a fundamental cause of X0 , then by the transitivity of necessary causation, it follows that X is a fundamental cause of Y. It is true that X0 is a more proximate cause of Y than is X, but this is consistent with both X and X0 being fundamental causes of Y. Thus, the possibility of there being chains of necessary causes need not pose a problem to understanding fundamental causes as necessary causes. Indeed, this characterization captures the fact that an effect, captured using a typelevel description, having a single necessary cause is extremely low (See [55]). Moreover, depending on the research interests of the person(s) investigating fundamental causes, there may be several different research foci. For example, the focus may be on X, or X0 , or both. Alternatively, the focus may be on multiple levels of necessary causes such as when X is constituted by events or (sub-) types of events described using the vocabulary of social-context properties, and X0 is constituted by events or (sub-) types of events described using the vocabulary of non-socialcontext properties.

13 Armstrong [72], Schwartz [55] and Koopman, and Lynch [73]. As late as 1996, Pearce [59], wrote that modern epidemiologists rarely consider socioeconomic factors and the population perspective, except perhaps to occasionally adjust for social class in analyses of the health effects of tobacco smoke, diet, and other lifestyle factors in individuals.

123

Social epidemiologic concept of fundamental cause

481

A third, related problem, focuses on cases in which the causal relation between X and Y is mediated by one or more events that are not themselves either necessary or sufcient causes. For example, consider the following: X ! X0 ! X00 ! Y Let us further suppose that while X is a necessary cause of Y, and either an event or a (sub-) type of events described using social-context descriptions, it is not a necessary cause of either X0 or X00 , and that neither X0 nor X00 are either necessary or sufcient causes for Y. Does the requirement that all fundamental causes are necessary causes permit occurrences of this sort? The quick answer is that it had better since it is examples of just this kind that writers like Link and Phelan have in mind. As they write, the idea of fundamental cause captures the idea that a link is preserved between the fundamental cause and the effect even through changes in the mediating mechanisms [3]. Fortunately, these sorts of examples do not pose a problem. The claim that X is a necessary cause of Y is consistent with saying that there is no necessary chain of intermediary causes through which the causal impact of X on Y must pass. It may be that there must be some chain of intermediary causes, but depending on the population of interest and the etiological time-period, that chain of intermediary causes may change. To return again to Rothman, suppose that we have two causal complexes, C1 and C2, where the component causes of C1 are X, Y and Z, while the component causes of C2 are X, V, W. Further, let us suppose that both C1 and C2 are sufcient causes for some effect E, and that the common element of C1 and C2 works through the mediating agency of the other component causes. In this case, we can say that while C1 and C2 are sufcient causes for E, none of V, W, Y, and Z are either necessary or sufcient causes. However, if we per hypothesis, suppose that C1 and C2 are the only sufcient causes of E, then we can say that X is a necessary (but not a sufcient cause) of E. That is to say, not only is X necessary in that it is a non-redundant element of both C1 and C2, it is also necessary in the sense of being a non-eliminable cause (a necessary cause) of Y. Additionally, in this situation, on the assumption that we describe X in the vocabulary of social context properties, it follows that X is a fundamental cause, in the social epidemiological sense, of E. Returning to the original case of X ? X0 ? X00 ? Y, X0 and X00 are necessary component causes for Y only if X ? X0 ? X00 is the only sufcient cause for Y. In the case where X ? X0 ? X00 is the only sufcient cause for Y, and X is the only sufcient cause for X0 , and X0 is the only sufcient cause for X00 , we can say that the causal complex is the necessary and sufcient cause for Y. Here, because X ? X0 ? X00 is the only sufcient cause for Y, each of X, X0 and X00 are necessary causal component of the effect Y, though none of the three is singularly, or in conjunction with one other component cause, a sufcient cause of Y. This analysis also brings to the forefront an important reminder about the taxonomy of causes into necessary causes, sufcient causes, and necessary and sufcient causes: the taxonomy is not an exhaustive one. Put differently, it is possible for two events to be causally related to one another (e.g., X ? Y), where X is neither a necessary cause of Y nor a sufcient cause of Y (and so, not a necessary and sufcient cause of Y). Nevertheless, the taxonomy is useful because it permits us to focus on one of

123

482

A. Ward

the distinctive characteristics of fundamental causes, viz., that fundamental causes are necessary causes.

Conclusion The goal of research in social epidemiology (as well as health services research more generally) is not simply conceptual clarication or theoretical understanding, but more importantly it is to contribute to, and enhance the health of populations (and so, too, the people who constitute those populations). Undoubtedly, understanding how various individual risk factors such as smoking and obesity affect the health of people does contribute to this goal. However, what is distinctive of much on-going work in social epidemiology is the view that analyses making use of individual-level variables is not enough. In the spirit of Durkheim and Weber, S. Leonard Syme makes this point by writing that just as bad water and food may be harmful to our health, unhealthful forces in our society may be detrimental to our capacity to make choices and to form opinions conducive to health and well-being [76]. Advocates of upstream (distal) causes of adverse health outcomes propose to identify the most important of these unhealthful forces as the fundamental causes of adverse health outcomes. However, without a clear, theoretically precise and well-grounded understanding of the characteristics of fundamental causes, there is little hope in applying the statistical tools of epidemiology and the health sciences to hypotheses about fundamental causes, their outcomes, and policies intended to enhance the health of populations. It is only after characterizing the social epidemiological concept of fundamental cause in a theoretically respectable and robust way that it can enter the realm of health science, and provide the framework for well-crafted health policies. Providing a start to this process has been the goal of the present paper. References

1. Daniels, Norman, Bruce Kennedy, and Ichiro Kawachi. 2000. Justice is good for our health. In Is inequality bad for our health?, ed. Joshua Cohen and Joel Rogers, 333. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. 2. Robert, Stephanie A., and James S. House. 2000. Socioeconomic inequalities in health: An enduring sociological problem. In Handbook of medical sociology, ed. Chloe Bird, Peter Conrad and Allen Fremont, 5th ed., 7997. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. 3. Link, Bruce G., and Jo Phelan. 1995. Social conditions as fundamental causes of diseases. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 35, extra issue: 8094. 4. Link, Bruce G., and Jo Phelan. 1996. Editorial: Understanding sociodemographic differences in healththe role of fundamental social causes. American Journal of Public Health 86, no. 4: 471473. 5. Lutfey, Karen, and Jeremy Freese. 2005. Toward some fundamentals of fundamental causation: socioeconomic status and health in the routine clinic visit for diabetes. American Journal of Sociology 110, no. 5: 13261372. 6. Williams, David R. 1990. Socioeconomic differentials in health: A review and redirection. Social Psychology Quarterly 53, no. 2: 8199. 7. Link, Bruce G., and Jo Phelan. 2000. Evaluating the fundamental cause explanation for social disparities in health. In Handbook of medical sociology, ed. Chloe Bird, Peter Conrad and Allen Fremont, 5th ed., 3346. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

123

Social epidemiologic concept of fundamental cause

483

8. Phelan, Jo C., and Bruce G. Link. 2005. Controlling disease and creating disparities: A fundamental cause perspective. Journal of Gerontology series B, 60B: 2733. 9. Rothman, Kenneth J. 2002. Epidemiology: An introduction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 10. Rothman, Kenneth J. 1976. Causes. American Journal of Epidemiology 104, no. 6: 587592. 11. Rothman, Kenneth J., and Sander Greenland. 1998. Causation and causal inference. In Modern epidemiology, ed. Kenneth Rothman and Sander Greenland, 2nd ed., 728. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. 12. Pearl, Judea. 2000. Causality: Models, reasoning, and inference. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 13. Kim, Jaegwon. 1993. Causation, nomic subsumption, and the concept of event. In Supervenience and mind: Selected philosophical essays, ed. Jaegwon Kim, 321. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 14. Rothman, Kenneth J., and Sander Greenland. 2005. Causation and causal inference in epidemiology. American Journal of Public Health Supplement 1, 95, no. S1: S144S150. 15. Parascandola, M., and D.L. Weed. 2001. Causation in epidemiology. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 55: 905912. 16. Karhausen, L.R. 2000. Causation: The elusive grail of epidemiology. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 3: 5967. 17. Charlton, Bruce G. 1996. Attribution of causation in epidemiology: Chain or mosaic? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 49, no. 1: 105107. 18. Bigelow, John, and Robert Pargetter. 1990. Metaphysics of causation. Erkenntnis 33: 89119. 19. Susser, Mervyn. 1973. Causal thinking in the health sciences: Concepts and strategies in epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press. 20. Nowak, Stefan. 1960. Some problems of causal interpretation of statistical relationships. Philosophy of Science 27, no. 1: 2338. 21. Mellor, D.H. 1995. The facts of causation. London: Routledge. 22. Glymour, Bruce. 2003. On the metaphysics of probabilistic causation: Lessons from social epidemiology. Philosophy of Science 70: 14131423. 23. Hausman, Daniel M., and James Woodward. 1999. Independence, invariance and the causal Markov condition. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 50: 521583. 24. Hausman, Daniel M. 1998. Causal asymmetries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 25. Hitchcock, Christopher. 1995. The Mishap at Reichenbach fall: Singular vs. general causation. Philosophical Studies 78: 257291. 26. Pearce, Neil. 1990. White Swans, Black Ravens, and Lame Ducks: Necessary and sufcient causes in epidemiology. Epidemiology 1, no. 1: 4750. 27. Marini, Margaret Mooney, and Burton Singer. 1988. Causality in the social sciences. Social Methodology 18: 347409. 28. Monteore, Alan. 1956. Professor Gallie on necessary and sufcient conditions. Mind 65, no. 260: 534541. 29. Greenland, Sander, and Babette Brumback. 2002. On overview of relations among causal modeling methods. International Journal of Epidemiology 31: 10301037. 30. Mackie, J.L. 1965. Causes and conditions. American Philosophical Quarterly 2, no. 4: 245264. 31. Mackie, J.L. 1974. The cement of the universe: A study of causation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 32. Mosley, Albert. 2004. Does HIV or poverty cause AIDS? Biomedical and epidemiological perspectives. Theoretical Medicine 25: 399421. 33. Nagel, Ernest. 1987. The structure of science: Problems in the logic of scientic explanation, 2nd ed. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Co. 34. Kelsey, Jennifer L., Alice S. Whittemore, Alfred S. Evans, and W. Douglas Thompson. 1996. Methods in observational epidemiology, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 35. Eells, Ellery. 1991. Probabilistic causality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 36. Popper, Karl R. 1965. Conjectures and refutations: The growth of scientic knowledge. New York: Harper Torchbooks. 37. Popper, Karl R. 1985. The problem of induction. In Popper selections, ed. David Miller, 101117. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 38. Van Fraassen, Bas C. 1980. The scientic image. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 39. Woodward, James. 2003. Making things happen: A theory of causal explanation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

123

484

A. Ward

40. Maldonado, George, and Sander Greenland. 2002. Estimating causal effects. International Journal of Epidemiology 31: 422429. 41. House, James S. 2002. Understanding social factors and inequalities in health: 20th century progress and 21st century prospects. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 43, no. 2: 125142. 42. Link, Bruce G., Mary E. Northridge, Jo C. Phelan, and Michael L. Ganz. 1998. Social epidemiology and the fundamental causal concept: On the structuring of effective cancer screens by socioeconomic status. The Milbank Quarterly 76, no. 3: 375402. 43. Williams, David R., and Chiquita Collins. 1995. U.S. socioeconomic and racial differences in health: Patterns and explanations. Annual Review of Sociology 21, 349386. 44. Phelan, Jo C., et al. 2004. Fundamental causes of social inequalities in mortality: A test of the theory. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 45, no. 3: 265285. 45. Dutton, D.B., and S. Levine. 1989. Overview, methodological critique, and reformulation. In Pathways to health, ed. J.P. Bunker and D.S. Gomby, 2969. Menlo Park, CA: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. 46. Montgomery, Laura E., John L. Kely, and Gregory Pappas. 1996. The effects of poverty, race, and family structure on U.S. childrens health: Data from the NHIS, 1978 through 1980 and 1989 through 1991. American Journal of Public Health 86, no. 10: 14011405. 47. Hempel, Carl G. 1965. Typological methods in the natural and the social sciences. In Aspects of scientic explanation and other essays in the philosophy of science, ed. Carl G. Hempel, 155171. New York: The Free Press; Salmon, Wesley C. 1998. Causality and explanation. New York: Oxford University Press. 48. Ehring, Douglas. 1997. Causation and persistence: A theory of causation. New York: Oxford University Press. 49. Weber, Max. 1968. The theory of social and economic organization. Translated by A.M. Henderson and Talcott Parsons. New York: The Free Press. 50. Lynch, John, and George Kaplan. 2000. Socioeconomic position. In Social epidemiology, ed. Lisa Berkman and Ichiro Kawachi, 1335. New York: Oxford University Press. 51. Moftt, Robert. 2003. Causal analysis in population research: An economists perspective. Population and Development Review 29, no. 3: 448458. 52. Link, Bruce G., and Jo Phelan. 2002. McKeown and the idea that social conditions are fundamental causes of diseases. American Journal of Public Health 92, no. 5: 730732. 53. Diez-Roux, Ana V. 1998b. On genes, individuals, society, and epidemiology. American Journal of Epidemiology 148, no. 11: 10271032. 54. Baron, Reuben M., and David A. Kenny. 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51, no. 6: 11731182. 55. Schwartz, S., E. Susser, and M. Susser. 1999. A future for epidemiology? Annual Review of Public Health 20: 1533. 56. Tesh, Sylvia Noble. 1988. Hidden arguments: Political ideology and disease prevention policy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. 57. Emmons, Karen M. 2000. Health behaviors in a social context. In Social epidemiology, ed. Lisa F. Berkman and Ichiro Kawachi, 242266. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 58. Beland, Francois, Stephen Birch, and Greg Stoddart. 2002. Unemployment and health: Contextuallevel inuences on the production of health in populations. Social Science and Medicine 55: 20332052. 59. Pearce, Neil. 1996. Traditional epidemiology, modern epidemiology, and public health. American Journal of Public Health 86, no. 5: 678683. 60. Durkheim, Emile. 1982. The rules of sociological methodsecond edition. In The rules of sociological method and selected texts on sociology and its methods, ed. Steven Lukes, translated by W.D. Hall, 31163. New York: The Free Press (rst published in 1901). 61. Giddens, Anthony. 1984. The constitution of society. Berkeley: University of California Press. 62. Wells, Barbara L., and John W. Horm. 1988. Targeting the underserved for breast and cervical cancer screening: The utility of ecological analysis using the national health interview survey. American Journal of Public Health 88, no. 10: 14841489. 63. Susser, Mervyn. 1994. The logic in ecological: I. The logic of analysis. American Journal of Public Health 84, no. 5: 825829. 64. Selvin, Hanan C. 1958. Durkheims suicide and the problems of empirical research. American Journal of Sociology 63, no. 6: 607619.

123

Social epidemiologic concept of fundamental cause

485

65. Morgenstern, Hal. 1982. Uses of ecological analysis in epidemiologic research. American Journal of Public Health 72, no. 12: 13361344. 66. Diez-Roux, Ana V. 1998a. Bringing context back into epidemiology: Variables and fallacies in multilevel analysis. American Journal of Public Health 88, no. 2: 216222. 67. Collins, Randall. 1981. On the microfoundations of macrosociology. American Journal of Sociology 86, no. 5: 9841014. 68. Betson, David M., and Jennifer L. Warlick. 2006. Measuring poverty. In Methods in social epidemiology, ed. J. Michael Oakes and Jay S. Kaufman, 112133. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. 69. Ross, Catherine E., and John Mirowsky. 1995. Does employment affect health? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36, no. 3: 230243. 70. Gottfredson, Linda S. 2004. Intelligence: Is it the epidemiologists elusive fundamental cause of social class inequalities in health? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 86, no. 1: 174199. 71. Schulz, Amy, and Mary E. Northridge. 2004. Social determinants of health: Implications for environmental health promotion. Health Education and Behavior 31, no. 4: 455471. 72. Armstrong, Donna. 1999. Controversies on epidemiology, teaching causality in context at the University of Albany, School of Public Health. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 2: 8184. 73. Koopman, James S., and John W. Lynch. 1999. Individual causal models and population models in epidemiology. American Journal of Public Health 89, no. 8: 11701174. 74. Susser, Mervyn, and Ezra Susser. 1996. Choosing a future for epidemiology: II. From black box to Chinese boxes and eco-epidemiology. American Journal of Public Health. 86, no. 5: 674677. 75. Duncan, Craig, Kelvyn Jones, and Graham Moon. 1996. Health-related behavior in context: A multilevel modeling approach. Social Science and Medicine 42, no. 6: 817830. 76. Syme, S. Leonard. 1994. The social environment and health. Daedalus 23, no. 4: 7986.

123

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Journey Toward OnenessDocumento2 pagineJourney Toward Onenesswiziqsairam100% (2)

- Expense ReportDocumento8 pagineExpense ReportAshvinkumar H Chaudhari100% (1)

- Cantorme Vs Ducasin 57 Phil 23Documento3 pagineCantorme Vs Ducasin 57 Phil 23Christine CaddauanNessuna valutazione finora

- X3 45Documento20 pagineX3 45Philippine Bus Enthusiasts Society100% (1)

- Rationality and RelativismDocumento31 pagineRationality and RelativismSamuel Andrés Arias100% (1)

- Transportation Systems ManagementDocumento9 pagineTransportation Systems ManagementSuresh100% (4)

- Solar - Bhanu Solar - Company ProfileDocumento9 pagineSolar - Bhanu Solar - Company ProfileRaja Gopal Rao VishnudasNessuna valutazione finora

- Alkyl Benzene Sulphonic AcidDocumento17 pagineAlkyl Benzene Sulphonic AcidZiauddeen Noor100% (1)

- 2012 Narrative Criticism A Systematic Approach To The Analysis of StoryDocumento9 pagine2012 Narrative Criticism A Systematic Approach To The Analysis of StorySamuel Andrés AriasNessuna valutazione finora

- Causes RothmanDocumento6 pagineCauses RothmanSamuel Andrés AriasNessuna valutazione finora

- New Challenges For Telephone Survey Research in The Twenty-First CenturyDocumento17 pagineNew Challenges For Telephone Survey Research in The Twenty-First CenturySamuel Andrés AriasNessuna valutazione finora

- Practice of EpidemiologyDocumento9 paginePractice of EpidemiologySamuel Andrés AriasNessuna valutazione finora

- 1992 Repetition Strain Injury in AustraliaDocumento19 pagine1992 Repetition Strain Injury in AustraliaSamuel Andrés AriasNessuna valutazione finora

- 2004 Beyond RCT - AjphDocumento6 pagine2004 Beyond RCT - AjphSamuel Andrés AriasNessuna valutazione finora

- Intro Ducci OnDocumento3 pagineIntro Ducci OnSamuel Andrés AriasNessuna valutazione finora

- 2008 Epidemiologu Core Competencies - Moser MDocumento9 pagine2008 Epidemiologu Core Competencies - Moser MSamuel Andrés AriasNessuna valutazione finora

- 2014 Increasing Value, Reducing Waste 3Documento10 pagine2014 Increasing Value, Reducing Waste 3Samuel Andrés AriasNessuna valutazione finora

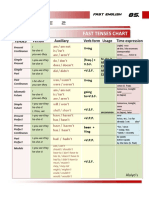

- Table 2: Fast Tenses ChartDocumento5 pagineTable 2: Fast Tenses ChartAngel Julian HernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- Infinivan Company Profile 11pageDocumento11 pagineInfinivan Company Profile 11pagechristopher sunNessuna valutazione finora

- Wine Express Motion To DismissDocumento19 pagineWine Express Motion To DismissRuss LatinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Second Grading Science 6 Worksheet 16 Code: S6Mtiii-J-5Documento3 pagineSecond Grading Science 6 Worksheet 16 Code: S6Mtiii-J-5Catherine Lagario RenanteNessuna valutazione finora

- RBI ResearchDocumento8 pagineRBI ResearchShubhani MittalNessuna valutazione finora

- RAN16.0 Optional Feature DescriptionDocumento520 pagineRAN16.0 Optional Feature DescriptionNargiz JolNessuna valutazione finora

- Merger and Acquisition Review 2012Documento2 pagineMerger and Acquisition Review 2012Putri Rizky DwisumartiNessuna valutazione finora

- First Summative Test in TLE 6Documento1 paginaFirst Summative Test in TLE 6Georgina IntiaNessuna valutazione finora

- OECD - AI Workgroup (2022)Documento4 pagineOECD - AI Workgroup (2022)Pam BlueNessuna valutazione finora

- Options TraderDocumento2 pagineOptions TraderSoumava PaulNessuna valutazione finora

- Taller InglesDocumento11 pagineTaller InglesMartín GonzálezNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 PDFDocumento176 pagine1 PDFDigna Bettin CuelloNessuna valutazione finora

- Schmemann, A. - Introduction To Liturgical TheologyDocumento85 pagineSchmemann, A. - Introduction To Liturgical Theologynita_andrei15155100% (1)