Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Of Brics and Brains: Comparing Russia With China, India, and Other Populous Emerging Economies

Caricato da

vinodoracledDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Of Brics and Brains: Comparing Russia With China, India, and Other Populous Emerging Economies

Caricato da

vinodoracledCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Of BRICs and Brains: Comparing Russia with China, India, and Other Populous Emerging Economies

Julian Cooper1

Abstract: A noted British economic analyst and observer of current developments in Russia compares that countrys emerging economy with those of China, India, eight other populous emerging states, and the United States. The focus of the comparison is on the extent to which these countries exhibit potential for functioning as knowledge-based economies. The four pillars of such economies are identified as: (1) an educated and skilled population; (2) a network of R&D institutions; (3) a dynamic information infrastructure; and (4) a regime promoting the development of knowledge. Journal of Economic Literature, Classification Numbers: L86, O30, O57. 1 figure, 19 tables, 91 references. Key words: Russia, China, India, BRIC, R&D institutions, information infrastructure, Internet, Brazil, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Mexico, Philippines, Turkey, Vietnam.

efore the collapse of communism, efforts to compare the USSR with the United States were generally considered unproblematic. In present-day Russia, this comparison is still frequently made, even though the economic levels of the two countries are of a different order. Unlike the United States, without question one of the worlds most developed, high income, countries, Russia is classified by the World Bank as a middle-income country, with a 2004 per capita Gross National Income (GNI) between $826 and $10,065 per annum.2 In this set, those countries with GNI above $3,255 are termed upper-middle-income, while those below are lower-middle income. Russia made the transition between the two levels in 2004. It is one of a number of populous countries in this category, defined here as a country with a current population in excess of 100 million, or one forecast to attain this level by the year 2050. Of the various population forecasts available, the revised 2004 medium forecast of the United Nations Population Division has been taken as providing the most appropriate overall assessment. Table 1 shows middle-income countries in this category as of 2004. For reasons outlined below, the low-income countries of India and Vietnam are also included, as is the United States to provide a comparison with a populous high-income country. Of the 11 countries in Table 1 (excluding the U.S.), Russia had the highest per capita GNI (PPP) in 2004, but its place in the ranking of countries by size of population is expected to fall from fifth to ninth by 2050.3

1 Deputy Director, Centre for Russian and East European Studies (CREES), University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B14 2TT, United Kingdom. Email: j.m.cooper@bham.ac.uk. In preparing this article, the author was assisted by Michael Rassell and Minoru Yasuda of CREES, whose participation is gratefully acknowledged. The author is entirely responsible for the content and conclusions presented here. 2Unless otherwise specified, all figures denominated in dollars are in $US. 3If high- and low-income populous countries are also included, Russias ranking falls from seventh in 2005 to sixteenth in 2005; the additional countries forecast to have larger populations are the United States, Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Japan.

255

Eurasian Geography and Economics, 2006, 47, No. 3, pp. 255-284. Copyright 2006 by Bellwether Publishing, Ltd. All rights reserved.

256

EURASIAN GEOGRAPHY AND ECONOMICS

Table 1. Population and Per Capita Income of Middle-Income and Other Countries with Current or Future Populations Exceeding 100 Million, 20042005, 2025, and 2050

Population (thous.) Country Rank China India Indonesia Brazil Russia Mexico Vietnam Philippines Egypt Turkey Iran U.S.

aGross bGNI

2005 N Rank

2025 N Rank

2050 N

GNI per.capita, GNI per capita PPP, 2004($)b 2004a (US$) 1,290 620 1,140 3,090 3,410 6,770 550 1,170 1,310 3,750 2,300 41,400 5,530 3,100 3,460 8,020 9,620 9,590 2,700 4,870 4,120 7,680 7,550 39,710

1 1,315,844 2 1,103,371 3 222,781 4 186,505 5 143,202 6 107,029 7 84,328 8 83,054 9 74,033 10 73,193 11 69,515 298,213

1 1,441,426 2 1,395,496 3 263,746 4 227,930 5 129,230 6 129,381 8 104,343 7 109,084 9 101,092 10 90,565 11 89,042 325,723

2 1,392,307 1 1,592,704 3 284,640 4 253,105 9 111,752 5 139,015 8 116,654 6 127,068 7 125,916 11 101,208 10 101,944 394,976

National Income per capita by World Bank Atlas methodology. per capita by World Bank Purchasing Power Parity estimate (international dollars). Sources: Compiled by author from United Nations, 2005; World Bank, n.d.

In 2003, economists of the Goldman Sachs Research Institute caused a sensation when they introduced the idea of the BRIC economiesBrazil, Russia, India, and Chinaa set of large-population countries with relatively dynamic economies that could, if appropriate polices were pursued, occupy an increasingly important place in the global economy during the years to 2050 (Wilson and Purushothaman, 2003).4 According to their estimates, the combined GDP of the four BRIC countries could overtake that of the G6 countries (USA, Japan, France, Germany, Italy, and UK) by 2040. Of the BRIC economies, Russia would have the smallest GDP by 2050, but from 2028 onward Russia was projected to have a GDP larger than any of the four European G6 countries. In a new look at the BRICs in December 2005, the Goldman Sachs analysts reviewed an additional set of developing countries, termed the N-11 (Next Eleven), which includes the non-BRIC countries included in Table 1, plus Bangladesh, Korea, Nigeria, and Pakistan. Of the N-11, Mexico alone was identified as having the capacity to join the BRICs, with Korea as a possible outside contender (ONeill et al., 2005).5 These papers drew attention to the fact that some of todays relatively lowincome countries have the potential to become major actors on the world stage because they

acronym was first used in a 2001 Goldman Sachs economic paper (Goldman Sachs, 2001). this new paper, Russias growth prospects were moderated: overtaking all four European G6 countries was postponed until after 2035 (ONeill et al., 2005, p. 20). In March 2006, the accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers introduced yet another groupingan E7 bloc of emerging economies: the BRICs, plus Indonesia, Mexico, and Turkey (Hawksworth, 2006). It was forecast that by 2050 the E7 will have surpassed the aggregate GDP of the G7 by at least 75 percent. Russian GDP was forecast to grow in U.S.dollar terms at an average annual rate rate of 4.6 percent over the period 20052050, yielding a total GDP equivalent to that of France by 2050. I am grateful to John Hawksworth for providing access to this report.

5In 4The

JULIAN COOPER

257

possess two decisive characteristicsvery large populations and unusually favorable prospects for economic growth. For this reason, India and Vietnam have been included in the set of countries discussed in this article. 6 The 2003 Goldman Sachs report (Wilson and Purushothaman, 2003) received considerable attention in Russia itself, not the least because it provided external validation to Great Power aspirations widely prevalent in Russian elite circles. However, other voices raised doubts: perhaps Goldman Sachs had overstated Russias growth potential?7 Within the BRIC group, for a number of reasons, Russia stands out. First, unlike Brazil, India, and China, it has an economy currently heavily dependent on the exploitation of mineral wealth, above all hydrocarbons; second, it is forecast to have a sharply declining population, whereas the other countries face only a declining rate of population growth; third, Brazil, China, and India can be regarded without ambiguity as developing countries, but Russia is unusual as in some respects it can be regarded as a de-developing countryits capability in research and development, high technology, and military power has diminished over the past 15 years; and finally, compared with the other countries Russia has an exceptionally low population density, set to decline in the years to come.8 But the question arises, why should we compare Russia with these three countries only when there are more middleincome countries in the world with large populations? It may be instructive to assess Russias current standing and prospects in relation to a somewhat larger group of comparators. There is no claim here to originality in undertaking such an exercise; a broader set of countries was taken by Schleifer and Treisman (2004), for example, in their attempt to depict Russia as a normal country.9 There are many possible dimensions to a comparison of Russia with other largepopulation countries of a similar income group. Here we focus on one factor that could prove decisive for future rates of economic development: the extent to which these countries are showing potential as knowledge-based economies. Various terms have been employed (e.g. knowledge economy, new economy, information economy), but certain common features emerge, perhaps best summarized in a World Bank study (Dahlman and Aubert, 2001). In the contemporary world, rapidly developing economies tend to be those in which economic growth depends increasingly on the creation, acquisition, distribution, and use of knowledge. Four pillars of a knowledge-based economy have been identified: (1) an educated and skilled population able to advance and productively employ knowledge; (2) an effective innovation system, forming a network of research and development, R&D institutions, higher educational establishments, and firms and other organizations able to harness, adapt, and assimilate the existing stock of knowledge and create new knowledge and technologies; (3) a dynamic information infrastructure that can facilitate the effective

6The potential of Vietnam also emerges from the 2005 Goldman Sachs Report (ONeill et al., 2005). One other low- income country, Pakistan, was examined in detail, but it was decided that its current developmental potential as a knowledge-based economy did not merit inclusion. 7Thus one well-known economist, Kseniya Yudayeva, observed that this was rare positive news regarding Russias future, but noted that the Goldmann Sachs report took no account of government policy; in her view, growing state intervention made the achievement of the forecast growth problematic (Vedomosti, June 29, 2005). This view was echoed by another commentator, Marina Pustilnik (2005), who thought that it would remain a beautiful dream that Russia could overtake the standard of living on Germany or France by 2050 unless the government stopped interfering in business. 8In 2003, Russias population density was 8 people per km2, compared with 21 for Brazil, 138 for China, and 358 for India (World Bank, 2005c). 9However, their comparison considered per capita income levels only, not population.

258

EURASIAN GEOGRAPHY AND ECONOMICS

communication, dissemination, and processing of information; and (4) an economic and institutional regime providing appropriate incentives to promote the efficient use and development of knowledge.10 There are examples of economies exhibiting high rates of growth in countries where the knowledge component is not predominant. This is indeed the case with Russia. But in the evolving globalized order it is becoming increasingly difficult to envisage a major economy developing at a rapid pace without a substantial knowledge-economy commitment. This appears to be recognized in Russia as well. In February 2006, speaking in Nizhniy Novogord at a State Council meeting devoted to information and communication technologies, Russias President Vladimir Putin declared that, The most important task of the economy is diversification, a switch to completely new high-technology modes of development, and a gradual withdrawal from the extraordinary dependence on natural resources, oil and gas.11 In following sections of this paper, Russias standing and progress in relation to the four pillars are explored, using the other large-population countries that exhibit similar or lower developmental levels (set out in Table 1) as comparators. HUMAN CAPITAL AND EDUCATION A vital prerequisite for knowledge-based economic development is human capital, in particular a population with a reasonably high overall level of education and a certain minimum proportion with higher education in science, technology, and other economically relevant disciplines. At first glance, this represents a significant relative strength of Russia. The Soviet Union possessed a well-developed educational system with considerable strength in higher education, biased toward natural sciences and technology. However, since the collapse of the Soviet empire, negative trends have emerged, especially in relation to health and life expectancy. Russia is almost unique in having experienced a decline in its rating based on the United Nations Human Development Index, as shown in Table 2, based on UNDP (2005). In relation to the chosen comparator countries, Russias overall position remains strong, although Mexico has pulled ahead and is the only country in the high human development category (the rest being medium). However, some other countries have been catching up at a rapid pace, particularly China, Brazil, the Philippines, and Turkey. If present trends continue, Russias ranking among the 11 countries could fall to a quite significant degree within the next five years. However, Russia still maintains a healthy lead in one of the components of the overall index, namely in education, where its rating remains very high, almost on a par with the United States. But, again, other countries are rapidly closing the gap, although it is noteworthy that India lags to a considerable degree. Looking to the future, the significance of overall demographic trends cannot be understated. Countries with relatively youthful populations, which now devote considerable attention to raising educational standards, can be expected to be strongly placed for future development of the knowledge economy. In this respect, Russias position is not favorable, as is evident from Table 3. Of the 11 countries, Russia has the smallest proportion of people under 15 years of age, and according to the most recent UN forecast, the situation will not change in the years leading to 2015, when Russia will also have by far the largest share of people older than 65. As a percentage of GDP, Russias spending on education lags behind

10Adapted 11For

from Dahlman and Aubert (2001, p. 4). more on the meeting, see the February 16, 2006 edition of strana.ru [http://www.strana.ru/273621.html].

JULIAN COOPER

259

Table 2. UN Human Development Index, 19902003, including the 2003 Education Index

2003 Country Brazil China Egypt India Indonesia Iran Mexico Philippines Russia Turkey Vietnam U.S.

Source: UNDP, 2005.

1990 0.719 0.627 0.579 0.513 0.625 0.650 0.764 0.720 0.817 0.678 0.617 0.916

1995 0.747 0.683 0.611 0.546 0.663 0.694 0.782 0.736 0.770 0.709 0.660 0.929

2003 0.792 0.755 0.659 0.602 0.697 0.736 0.814 0.758 0.795 0.750 0.704 0.944

Ranking, n = 159 63 85 119 127 110 99 53 84 62 94 108 10

Education index 0.89 0.84 0.62 0.61 0.81 0.74 0.85 0.89 0.96 0.82 0.82 0.97

Table 3. Education Spending and Demographic Trends, 20002015

Public expenditure on Expected Public expenditure tertiary education as a years of on education as a percentage of total education percentage of GDP, education expenditure 20002002 in 2002a 20002002 4.2 2.1c n.d. 4.1 1.2 4.9 5.3 3.1 3.8 3.7 n.d. 5.7 21.6 21.0c n.d. 20.3 23.6 17.1 19.6 14.0 16.2d 21.7 n.d. 25.2 16.1 11.9 12.0 9.8 11.9 n.d. 13.2 11.8 14.9 12.0 n.d. 16.8 Population under Population 15 as percent of over 65 as total percent of total 2003 2015Fa 2015Fa 28.4 22.7 34.3 32.9 29.0 31.1 32.1 36.1 16.2 29.7 31.1 21.1 25.4 18.5 31.4 28.0 25.2 25.6 25.5 30.0 16.4 25.8 25.0 19.7 7.8 9.6 5.5 6.2 6.4 4.9 7.1 4.9 13.3 6.2 5.6 14.1

Country

Brazil China Egypt India Indonesia Iran Mexico Philippines Russia Turkey Vietnam U.S.

aFrom bF

primary to tertiary education, excluding those under five years of age. = forecast. cFor 1999. dFor 2002. Sources: Compiled by author from UNDP, 2005, except for China, 1999; Russia, tertiary education; and expected years of education under current conditions, calculated from UNESCO, various dates.

260

EURASIAN GEOGRAPHY AND ECONOMICS

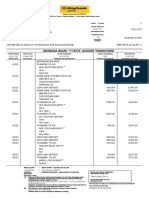

Fig. 1. Universities in the BRIC countries, Mexico, and Turkey among the worlds top 200 and 500 universities. Top 200: ranking by peer review, survey of employers, citations, staffing levels, and percentage of international staff and students (World University, 2005). Top 500: annual ranking by Shanghai Jiao Tong University (2005).

that of a number of other middle-income, large-population countries, notably Mexico, Iran, and Brazil. In relation to the United States, which has a more comparable age distribution, the spending gap is significant. However, apart from Brazil, Russia has the longest period during which education is pursued, and by this indicator India falls quite far behind. Since 1991, Russias higher educational system has been undergoing a painful process of adaptation to much lower levels of funding, and there has been mounting concern at an official level that standards have been falling. In the words of Russias first science minister, Boris Saltykov, A reform of education is indeed a necessary but clearly not sufficient condition for a turn to an innovational economy. It is needed because the level of training of specialists in all fields in Russia lags catastrophically behind modern demands (Saltykov, 2005). Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that many students have sought training abroad, especially at the postgraduate level. Over the same period, there have been significant advances in the provision of higher education in comparator countries, notably in China and India. The results of a recent authoritative ranking of the worlds top universities in terms of teaching and research are shown in Figure 1. Had a similar ranking been compiled in 1990, there is little doubt that Russias standing would have been much more favorable. In the authors view, there is a widespread tendency to overstate the level of human capital in Russia, with insufficient appreciation of the extent to which the legacy of Soviet times has depreciated, and of the depth of problems afflicting the educational system, plagued by inadequate funding for almost 15 years. In Russia, complacency at the official level does not seem to be present: in March 2005, for example, German Gref, the economy minister, identified the inadequate development of human capital as one of the five principal problems facing the economy.12 Notwithstanding the problems, it should be acknowledged that, all

JULIAN COOPER

261

countries considered, Russia possesses a very well educated population and many extremely talented young people. RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT AND NATIONAL INNOVATION SYSTEMS The USSR maintained a very strong commitment to research, with a system of R&D of considerable scale in terms of personnel and spending. However, this research effort was oriented strongly toward military needs, and the planned economy was notoriously counterinnovative, with highly inappropriate incentives and institutions. Since the collapse of communism, this R&D effort has shrunk in Russia, not so much as a result of deliberate state policy but as a spontaneous outcome of severe budget constraints, depressed rates of pay, and an economy that until now has generated modest demand for product and process innovations. Furthermore, the military orientation of the R&D system remains high. In 1990, Russia had 993,000 researchers, and domestic spending on R&D was just over 2 per cent of GDP (Tsentr, 1998, p. 42). In 2005 the equivalent numbers were 400,000 and 1.21 per cent. Moreover, the number of researchers continues to decline (Ministerstvo obrazovaniye, 2006, p. 168). In 2005, the average age of researchers was 48 years, including candidates of science 53 and doctors of science 61 (ibid., p. 169). Whereas in 1994, 35 percent of researchers were over the age of 50, by 2002 that share had risen to 49 percent. While there was a slight increase in the proportion under 30 years of age, many young scientists work only for brief periods in research before moving to more remunerative employment (Dezhina and Yegerev, 2005, p. 7).13 While some Russian scientists have gone abroad, science policy specialist Irina Dezhina is certainly correct in her assessment that the extent of the brain drain is probably exaggerated. Much more significant has been the internal brain drainresearchers leaving R&D to work in other sectors of the economy (Dezhina, 2005, p. 9).14 Of the total Russian expenditures on R&D, the share of the business sector is only one-fifth, and almost three-quarters of R&D organizations remain in state ownership (Ministerstvo ekonomicheskogo, 2006b, p. 169). For some comparator countries up-to-date data are unavailable, to a large extent reflecting a lack of priority for R&D in the countries concerned. Table 4 summarizes the available evidence. It can be seen that, notwithstanding the contraction since the early 1990s, Russia occupies a strong position in terms of research spending and personnel. However, China now has a much larger research base in absolute terms, while India, and to a lesser extent Brazil, are catching up. Measurement of research output is not an easy undertaking, but using scientific publication as a proxy, one finds that China and India have become significant competitors. The Russian governments medium-term program of socioeconomic development envisages a substantial increase in R&D spending, forecast to rise to 1.8 percent of GDP by 2008 and 2.0 percent in 2010 (Programma, 2006, p. 126). 15 Without far-reaching reforms and

ministers comments were summarized on http://www.economy.gov.ru, March 29, 2005. has been estimated that the average period of time young scientists work in the field of research is 79 years (Dezhina and Yegorev, 2005, p. 8). 14According to the Ministry of Science and Education (Ministerstvo obrazovaniya, 2006, p. 10), between 1989 and 2002 some 20,000 scientists left Russia to work abroad on a permanent basis, and a further 35,000 to work to temporary contracts. However, it is acknowledged that those who left tended to be the most talented. 15According to the strategy for science and innovation, 2.5 percent GDP is the target for 2015 (Ministerstvo obrazovaniya, 2006, p. 4).

13It 12The

262

EURASIAN GEOGRAPHY AND ECONOMICS

Table 4. Scale of R&D Effort

Researchers employed in R&D (FTE) 59,838a 810,525 117,528 31,2561 27,626 401,425 23,995 Researchers in R&D per million inhabitants 352 633 120 182 484 274 157 2,784 345 R&D spending as percent of GDP 1.0 1.2 0.2 0.8 0.2 0.4 0.2 1.2 0.7 0.2 2.7 Scientific-technical journal articles per million inhabitants, 2001 7,705 20,978 1,548 11,076 207 995 3,209 158 15,846 4,098 158 200,870

Country

Year

Brazil China Egypt India Indonesia Iran Mexico Philippines Russia Turkey Vietnam U.S.

2000 2002 2000 1998 1988 2001 2002 1992 2004 1997 1997 2002

4,526

aHead count, not FTE (full-time equivalent). Source: Compiled by author from UNESCO, various dates, except Russia (researchers and percent of R&D spending of GDP; from Goskomstat Rossii, 2005, pp. 586, 594); Vietnam (R&D spending as percent of GDP; from Sinh, 2004); and scientific-technical journal articles per million inhabitants (from World Bank, 2005c).

much-improved incentives for talented young people to take up a career in science, it is difficult to see how these targets will be realized. Meanwhile, China has already reached Russias GDP share, achieving 1.23 percent in 2004, and has the same target, 2.0 percent, by 2010, rising to 2.5 percent by 2020 (China Internet Information Center, 2006a, 2006c).16 Detailed citation analysis provides some insights into the relative strength of Russia and other countries in various scientific disciplines. The Thomson ScientificISI Web of Knowledge provides relevant indicators over 10-year periods. For the period 19952005, the United States led with 12.92 citations per published scientific paper, Brazil had 4.73, India 3.53, Russia, 3.39, and China 3.32. For Mexico, equivalent data cover the period 19922002, when citations per paper reached 4.15. In terms of the number of published papers over the period 20002004, Chinas world share was 4.6 percent, but in materials science 11.56, physics 9.15, chemistry 6.89, engineering 6.89, geoscience 5.76, and computer science 5.48. Russias overall share was 3.24 percent, with larger shares in physics (8.47 percent), geosciences (7.77), space science (7.47), chemistry (6.10), mathematics (4.79), and materials science (3.41); in computer science, Russias share was only 1.0 percent, below Indias share of 1.46. India, with an overall share of 2.39 percent, also had above-average shares in materials science, chemistry, physics, engineering, and space science, but also considerable strength in agricultural sciences (5.4 percent), plant-animal sciences, and pharmacology (Sci-bytes, 2006). Language of publication is clearly a factor, but Chinas success in many fields of science suggests that its importance should not be overstated.

16Readers should note that the 2004 GDP share is somewhat overstated, as it takes no account of the GDP series revision of late 2005 (accounting for the revision, the share would be ca. 1.1 percent). Turkey also has a 2 percent of GDP target in 2010 for R&D spending as a share of GDP (European Trend, 2005, p. ii).

JULIAN COOPER

263

While Russia possesses a relatively large R&D capability in terms of organizations and personnel, there is much evidence that the country does not have an effective innovation system. Substantial barriers remain between the business sector and the research activities of the Academy of Sciences and the higher educational system, demand for new technologies remains weak, and the business sector itself has been slow to develop its own R&D capabilities. It is debatable whether one can speak of a developed Russian National Innovation System (NIS) in the sense of a coherent set of institutions working effectively together to secure innovation on a routine basis. Dezhina and Saltykov (2005) are surely correct in seeing the current system as transitional between the administrative-command innovation system characteristic of the USSR and a modern, market-type NIS, the creation of which remains a key policy objective. However, underdeveloped NISs are also a feature of other emerging economies. It is not clear that the situation in Russia is worse than in the comparator countries, although with the exceptions of China and Vietnam, they are not faced with the task of restructuring innovation systems originally developed to serve the needs of a nonmarket economic system. In China, however, realization that the Soviet-type innovation system required major reform appears to have influenced policy over a longer period, with structural changes dating back to the mid-1980s (Motohashi and Yun, 2005, pp. 2-9). In other countries, the problems identified are familiar. Thus a World Bank study of Brazil found that the innovation system contains serious gaps, with few researchers in the business sector (World Bank, 2002, pp. 126-129). Iran has a relatively strong science and technology infrastructure, but innovation activities are not demand driven, with a large role being played by state-owned institutions (UNCTAD, 2005, pp. 2-7). According to a World Bank study of competitiveness in Mexico, that country has one of the least effective and inefficient innovation systems in Latin America (World Bank, 2005b, p. 2). In the Philippines, it is reported that R&D is weakly linked to production and dominated by the public sector (UNCTAD, 2003, pp. 59-62), but some promise is identified in Turkey, with strengths in entrepreneurship and the university sector (World Bank, 2004, pp. 24-27). While India cannot be said to have a developed NIS, it has some dynamic local innovation hubs, notably that of Bangalore, of a kind that Russia has yet to emulate (World Bank, 2005a, pp. 71-77). Overall, the state of Russias innovation system is not at present adequate to the task of developing a knowledge-based economy, and its weaknesses are giving rise to high-level concern. In the opinion of Arkadiy Dvorkovich (2006), head of President Putins Experts Directorate, unless innovative activity increases sharply, within five years it will not be possible to count on stable rates of growth. INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGIES (ICT) During the past 15 years, telecommunications have undergone radical change, and there have been dramatic transformations in the use and ubiquity of information technologies. These developments have far-reaching implications for the evolution of knowledge-based economies. We explore here the comparative performance of Russia, a country that in communist times was notoriously backward in ICTs. Is it now keeping pace with comparator countries having similar levels of development? With the rapid diffusion of mobile phones, the level of development of terrestrial, fixedline, telephone communications is becoming less important, although it remains important for the development of the Internet. In 1990, Russia had a substantial lead over comparator countries in the diffusion of terrestrial telephony, and has made further progress in recent years. However, as shown in Table 5, the lead has narrowed appreciably and if present trends

264

EURASIAN GEOGRAPHY AND ECONOMICS

Table 5. Main Telephone Lines per 1,000 Inhabitants, 19902004

Country Brazil China Egypt India Indonesia Iran Mexico Philippines Russia Turkey Vietnam U.S. 1990 65 6 30 6 6 40 65 10 140 122 2 545 1995 85 33 49 13 17 86 94 21 169 213 11 600 2000 182 115 86 32 32 149 126 40 220 273 32 663 2004 237 241 138 43 46 219 176 41 261a 265 70 606 Percentage increase, 19952004 179 630 182 231 171 155 87 95 54 24 536 1

aFor 2005, the ratio was 295 phone lines per 1,000 inhabitants (Russias IT, 2006). Sources: Compiled by author from ITU, 2005b; 2000 and 2004 figures are adjusted to account for more up-to-date data in World Bank, 2006, country tables.

are maintained Russia will soon be overtaken by China and Brazil. Indeed, according to Chinas information industry ministry, there will be 380 million fixed telephone users by the end of 2006, or approximately 390 per 1,000 inhabitants (China Internet Information Center, 2006b). According to the medium-term program of socioeconomic development to 2008, adopted by the Russian government in January 2006, terrestrial telephone density is forecast to rise to 380 in 2008 and 468 in 2012the latter corresponding to the 2004 level of Italy (Programma, 2006, p. 103). The table also shows that India, Indonesia, and the Philippines lag far behind, but Vietnam is now advancing rapidly. For countries with underdeveloped terrestrial telephone systems, the emergence of cellular mobile phones has made possible a very rapid spread of modern communications with greatly reduced investment in infrastructure. As Table 6 shows, Russia was initially rather slow adopting the new technology. In the year 2000, the country lagged behind all but India, Vietnam, Egypt, and Indonesia. Since 2002, the diffusion of mobile phones in Russia has been extremely rapid, putting it in the lead in this set of comparator countries, with a level of use per 1,000 people comparable with some Central European countries and higher than in the United States. However, Russia has made only limited progress in the diffusion of 3G mobile phone technology, and government action is now required to issue licenses to operators (3G, 2006). The level of development of communications technology is an important factor in the diffusion of the Internet, but an additional prerequisite is widespread access to computers. In this respect, Russias performance in recent years has been relatively strong, as can be seen from Table 7, based on International Telecommunication Union (ITU, 2005b). By this indicator, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam lag far behind comparator countries. According to the Russian governments medium-term program, the number of computers per 1,000 population

JULIAN COOPER

265

Table 6. Mobile Phone Subscribers per 1,000 Inhabitants, 19922005

Country Brazil China Egypt India Indonesia Iran Mexico Philippines Russia Turkey Vietnam U.S.

aMoscow bMobile

1992 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.2 3.5 0.9 1.0 43

1995 8.3 2.9 0.1 0.1 1.1 0.2 7.3 7.2 0.6 7.0 0.3 127

2000 137 66 21 4 18 15 142 38 22 247 12 389

2001 167 110 43 6 55 32 219 155 53 286 15 450

2002 201 160 67 12 55 34 258 194 120 335 23 489

2003 263 209 84 25 87 51 295 278 249 394 34 546

2004 363 255 109 44 135 62 366 399 516 480 60 610b

2005 468 291 180 68 171 106 437 470 836a 535 87 680

= 1,280 and St Petersburg = 1,100, from Ministerstvo ekonomicheskogo, 2006b, p. 167. phone use is relatively underdeveloped in the United States; in 2004, there were 10 countries with 1,000 or more users per 1000 inhabitants, Luxembourg being the leader with 1,194. Sources: Compiled by author from ITU, 2005b, except for: Brazil, end 2005, calculated from GSM, 2006; China, November 2005 from [http://english.sina.com/business/1/2005/1226/59479.htm] and forecast of 340 for end 2006 from China Internet Information Center, 2006b; Egypt, end 2005, Cell Phones, n.d.; India, calculated from Malik and de Silva, 2006; Indonesia, Mexico, Turkey, and the United States, calculated from China Tops, 2005; Iran, for October 2005, from [http://irantelecom.ir/dl/emp45.pdf], January 2006; Philippines, for June 2005, EIU, 2006; Russia, for end 2005, Ministerstvo ekonomicheskogo, 2006b, p. 167; Vietnam, forecast, November 2005, Tegic Communications, 2005.

Table 7. Personal Computers per 1,000 Inhabitants, 19952004

Country Brazil China Egypt India Indonesia Iran Mexico Philippines Russia Turkey Vietnam U.S. 1995 17.3 2.3 4.3 1.3 5.0 25.3 25.6 9.6 17.6 14.9 1.4 324.1 2000 50.1 15.9 12.6 4.5 10.2 62.8 57.6 19.3 63.3 40.1 7.5 585.2 2001 62.9 19.0 15.5 5.8 11.0 69.7 69.6 21.7 75.0 39.4 8.6 624.4 2002 74.8 27.7 16.6 7.2 11.9 75.0 83.0 27.7 88.7 43.1 9.8 659.8 2003 88.7 39.1 29.1 8.8 12.8 90.5 97.9 37.3 104.9 47.2 11.2 687.7 2004 107.1 40.9 32.9 12.1 13.6 105.3 106.8 44.6 131.8 51.2 12.7 740.6

is forecast to rise to 320 in 2008, the latter equivalent to the 2004 level of Italy, while the IT and communications ministry has a goal of 430 by 2010.17

17See

Soobshcheniye (2006, p. 103) and http://www.prec.ru/news, March 20, 2006.

266

EURASIAN GEOGRAPHY AND ECONOMICS

Table 8. Internet Users per 1,000 Inhabitants, 19952005

Country Brazil China Egypt India Indonesia Iran Mexico Philippines Russia Turkey Vietnam U.S.

aProvisional.

1995 1.1 0.5 0.3 0.3 0.3 0.4 1.0 0.3 1.5 0.8 93.9

2000 29.4 17.4 7.1 5.4 9.2 9.8 51.2 20.1 19.7 38.3 2.5 440.6

2001 46.6 25.7 9.3 6.8 20.1 15.6 74.7 25.6 29.3 51.1 12.4 501.0

2002 82.2 46.0 28.2 15.9 21.2 48.5 99.7 44.0 40.9 61.8 18.5 552.1

2003 102.0 61.5 43.7 17.5 37.6 72.4 120.0 49.4 68.3 84.9 43.0 555.8

2004 121.8 71.6 55.7 32.4 65.2 78.8 133.8 53.2 111.0 141.3 71.2 622.8

2005a 141.0 85.0 59.0 45.0 81.0 108.0 162.0 91.0 153.6

681.0

Sources: Compiled by author from ITU, 2005b, except: Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico, and U.S., calculated from Worldwide, 2006; China, 2005 from http://www.cnnic.net/en/iondex/00/ index/htm, January 19, 2006; Egypt (June 2005), Iran (end 2005), and Philippines (February 2005) from http://www. internetworldstats.com/asia/htm; and Russia, 2005 from Ministerstvo informatsionnykh, 2006.

Of the 11 countries under consideration, Russia was one of the first to adopt the Internet. The .su domain name was registered in September 1990, followed in April 1994 by the .ru domain. In the early years, the Internet developed mainly through the efforts of individual enthusiasts, with very little state involvement. However, by 2000 a number of comparator countries had moved ahead in the level of diffusion of Internet use, in particular Mexico, Turkey, Brazil, and the Philippines, with China rapidly narrowing the gap. As shown in Table 8, over the last five years Russia has maintained a fairly rapid pace of Internet development;18 the table also shows the extent to which India now lags behind the other countries. With little state involvement and control, Russian Internet developers have faced few obstacles in developing an impressive range of Internet hosts, and while lagging behind Brazil, Mexico, and Turkey, Russia is now far ahead of other countries where state oversight and regulation has been much more active (Table 9, based on ITU, 2005b). In this respect, the more liberally oriented nations have had a substantial advantage over countries such as China, Iran, Egypt, and Vietnam. Indias lag can be explained by general ICT backwardness rather than by actions of a heavy-handed state. In other respects, Russias Internet performance has been less impressive, especially in developing the infrastructural and institutional conditions essential for the rapid development of e-commerce and the use of the Internet in education, government, and other spheres of life. One index of this development is the stock of secure Internet servers. Compared with some other comparator countries, notably Brazil, Turkey, and Mexico, Russias rate of progress has been modest and, while behind in per capita terms, India is quickly catching up, as shown in Table 10, compiled from World Bank (2006a).

18For

background, see Perfiliev (2001)Ed.

JULIAN COOPER

267

Table 9. Internet Hosts per 10,000 Inhabitants, 19952004

Country Brazil China Egypt India Indonesia Iran Mexico Philippines Russia Turkey Vietnam U.S. 1995 1.3 0.1 0.1 0.1 1.5 0.3 1.5 0.9 22.7 2000 51.6 0.6 0.4 0.4 1.3 0.3 56.5 2.5 22.2 10.7 286.3 2001 95.7 0.7 0.4 0.8 2.2 0.4 92.6 3.9 24.1 15.5 372.5 2002 128.7 1.2 0.4 0.8 2.9 0.5 110.1 4.8 27.9 22.2 400.4 2003 179.3 1.3 0.5 0.8 2.9 0.8 130.6 5.9 42.2 50.8 557.8 2004 193.0 1.2 0.5 1.3 5.0 1.0 145.2 7.9 59.2 65.6 0.1 656.9

Table 10. Secure Internet Servers, 2000 and 2004 (per million people)

Country Brazil China Egypt India Indonesia Iran Mexico Philippines Russia Turkey Vietnam U.S. 2000 6.0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.3 0.0 2.6 0.9 2.0 3.2 0.1 273.8 2004 11.2 0.2 0.4 0.4 0.4 0.2 6.1 1.9 2.1 12.3 0.1 674.9

Another development now beginning to have a significant impact on the use of the Internet in business, education, government, and culture is the transition to broadband. There are a number of different modes of broadband access, with high speed modem and DSL as the most widely used. Here China is forging ahead at an impressive rate, while Russia also lags behind Brazil and Turkey, as shown in Table 11 (based on World Bank, 2006a). However, there is evidence that the adoption of broadband in Russia accelerated sharply in 2005 (Shirokopolosnyy, 2006). In an attempt to measure the overall level of development of the Internet, a number of organizations have devised summary indicators. One of the best known is the Network Readiness Index of the World Economic Forum. This ranks the more developed countries of the world according to the ICT environment; the readiness of individuals, business, and government to use ICT; and the actual levels of usage. In the most recent 2005 ranking, Russias

268

EURASIAN GEOGRAPHY AND ECONOMICS

Table 11. Availability of Broadbanda and International Internet Bandwidth, 20002004

Broadband subscribers (per thous. people) 2000 Brazil China Egypt India Indonesia Iran Mexico Philippines Russia Turkey Vietnam U.S.

aDSL

Country

International internet bandwidth (bits per person) 2000 5 2 0 1 1 1 9 2 21 9 0 394 2004 154 57 23 4 18 15 108 12 101 40 27 3,308

2004 12.8 16.5 0.4 0.6 0.3 0.2 3.1 0.3 0.9 0.8 0.6 129.1

0.6 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.2 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 25.1

and cable modems.

Table 12. ICT Network Readiness Rankings in 2005

Country Brazil China Egypt India Indonesia Iran Mexico Philippines Russia Turkey Vietnam U.S. WEF network EIU e-readiness readiness index, ranking, N = 115 N = 65 52 50 63 40 68 55 70 72 48 75 1 38 54 53 49 60 59 36 51 52 43 61 2

Sources: Compiled by author from EIU, 2005; WEF, 2006.

position is weak. A similar ranking is produced annually by the Economist Intelligence Unit in association with the IBM Institute for Business Value, but for a smaller set of countries. The 2005 e-readiness ranking was modified to take greater account of such new developments as broadband. In this ranking, Russias position is stronger, ahead of China, but behind India, as can be seen from Table 12.

JULIAN COOPER

269

Table 13. ITU Digital Opportunity Index (DOI)a

Country Brazil China Egypt India Indonesia Mexico Philippines Russia Turkey U.S. Ranking 34 32 31 40 38 27 37 30 28 13 Opportunity 0.49 0.64 0.83 0.35 0.47 0.78 0.51 0.78 0.68 0.97 Infrastructure 0.21 0.20 0.14 0.03 0.05 0.20 0.12 0.18 0.32 0.54 Utilization 0.12 0.09 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.08 0.03 0.04 0.03 0.30 DOI 0.27 0.31 0.33 0.14 0.18 0.35 0.22 0.34 0.34 0.60

aN = 40. No rankings for Iran and Vietnam. Opportunity, infrastructure, and utilization are each given a one-third share in calculating the value of the overall DOI.

The International Telecommunication Union has also been developing measures of digital capabilities. Its first attempt, the Digital Access Index, was not entirely satisfactory as it placed much emphasis on a countrys educational standards. More recently, however, a new measure, the Digital Opportunity Index (DOI), has been devised, which covers opportunity (mobile phone access, Internet and mobile fees), infrastructure (fixed line telephones, mobile phones, and Internet), and utilization (proportion of individuals using Internet, proportion of broadband subscribers). This new index is still under development, and only 40 countries thus far are included in the ranking. By that measure, Russias position is stronger, largely because opportunity is rated highly. By the DOI, Russia is ahead of China, Brazil and Brazil, but behind Mexico and roughly on a par with Turkey, as can be seen in Table 13 (from ITU, 2005a, p. 16). In the authors opinion, the DOI more accurately reflects Russias position than the index used by the WEF. In one respect, Russia has been relatively slow in taking advantage of the Internet. Ecommerce is still underdeveloped, whether business-to-consumer (B2C) or business-tobusiness (B2B). Hindrances have included the lack of appropriate legislation for the use of electronic signatures, limited use of credit cards making payments difficult, and consumer distrust of digital transactions. However, the volume of trading is steadily increasing, assisted by rapid growth in credit card use in the last year or two, and wider access to the Internet. In B2B development, the lead has been taken by some large public companies, in particular RAO UES the electricity company, which now makes many purchases by electronic means. Statistical data on e-commerce are still sporadic, but according to the National Association of Participants in Electronic Trade (NAUET), the volume of B2C was up to between $1.0 and $2.6 billion in 2005. The volume of B2B increased to $1.3 bn, and of state purchasing via the Internet to $2.1 billion, but 80 percent of this total was accounted for by the Russian Agency for Atomic Energy; total e-sales thus rose to roughly $6 billion (Vedomosti, March 31, 2006). According to the China Internet Development Research Centre, total e-commerce sales in China in 2005 reached $68.7 billion, including B2C $1.68 billion, triple the level of 2004 (Zhe, 2006).19 By volume of sales, Russia also lags far behind India, with its total 20032004

19For

comparison, retail e-commerce in 2005 in the United States amounted to $86 billion (Quarterly, 2006).

270

EURASIAN GEOGRAPHY AND ECONOMICS

e-commerce sales of $58 billion (IMAI, 2006) and Brazil, where total e-commerce sales in 2004 are estimated to have been between $35 and $59 billion (eBrazil, n.d.). In China, as in Russia and other comparator countries, e-commerce, especially retail, is constrained by payment problems, lack of trust, and concerns about the inadequate quality of some goods purchased on line. In some countries, such as Egypt, Indonesia, and Vietnam, an additional problem is that many websites are in English rather than in local languages (e.g., United Nations, 2003, p. 28; Purbo, 2003; UNESCO, n.d). In this respect Russia is much better placed, as almost from the outset Russian was the basic language of what is popularly known as Runet. In Russia and most of the comparator countries, government initiatives have been undertaken to promote the development of information societies, often with a focus on e-government and the use of ICT in education and culture. Thus Russia adopted an ambitious Electronic Russia (20022010) program in 2002 (e.g., see Ministerstvo ekonomicheskogo, 2006a), and China a similar program in the same year (Xinhuanet, 2002). In the case of Egypt, an Egypt Information Society initiative was launched by President Mubarak in September 1999 (Egypt Information, n.d.) and a new Ministry of Communications and IT was established the following month. In 2001 Indonesia adopted a five-year action plan for ICT development (Five-Year, 2001), while in India the Planning Commission issued a report on India as Knowledge Superpower: Strategy for Transformation in 2001, followed by India Vision 2020 in 2002 (e.g., see World Bank, 2005a). To varying degrees, the governments of this set of large emergent economies have commitments to harness ICTs to economic and social advancement. CLUSTERS, PARKS, AND ZONES In July 2005, President Putin signed a decree on the creation of special economic zones. By end of the year a decision had been taken to create six such zones, of which four are to be focused on high technology and innovation: Zelenograd (just outside Moscow), microelectronics; Dubna (Moscow region), nuclear and technologies based on physical sciences; St. Petersburg, IT; and Tomsk, new materials. In addition, two industrial production zones are to be created, one in the Lipetsk region, for the manufacture of household electronics and perhaps furniture, and the second in Yelabuga, Tatarstan, for vehicle components and hi-tech petrochemical products. The zones will benefit from some tax and customs concessions.20 This initiative followed Putins December 2004 visit to India, where he visited the dynamic IT and software innovation hub of Bangalore. This clearly made a large impression, for soon after his return to Russia, Putin called for the creation of similar zones to promote the development of IT and other high-technologies. Responsibility for leading the development of special zones was vested with the Ministry of Economic Development and Trade (MERT), which established a new agency to lead the process. Regions and cities were invited to submit proposals for their creation and the government approved the six projects eventually selected, the establishment of which is to be aided by investment from the federal budget. From the outset, it was clear that the approach to creating innovation zones did not command universal support. In particular, the Ministry of Information Technology and Communications has been vigorously promoting its own alternative in the form of IT parks, specifically designed to foster the development of ICTs and software. The Ministry intends to

20For

additional information, see http://www.outsourcing-russia.com/docs/doc=1062, December 24, 2005.

JULIAN COOPER

271

create five such parks, located in St. Petersburg, Novosibirsk, Nizhniy Novgorod, and Dubna and Chernogolovka in the Moscow region (Yankevich, 2005). Critics charge, not without reason, that the approach of MERT is too centralized and inflexible, with such a large role for the state that they are unlikely to be very attractive to private investors. In April 2006, Putin himself expressed reservations, observing that it was curious that countless bureaucratic procedures had developed even though the initiative was intended to reduce administrative obstacles and delays.21 In developing IT parks, innovation zones, and similar special arrangements for the promotion of new technologies, Russia is following the practice not only of India, but of almost all the comparator countries, but often with considerable delay. In China, high-technology development zones have played a major role in the countrys economic rise in recent years. In Egypt, the first smart village is under development near Cairo, backed by private investors and the Egyptian government, with potential accommodation for 30,000 people (UNIDO, 2006a). Iran has developed the Guilan Science and Technology Park, with a particular focus on ICT, the Khorasan Science and Technology Park, and under development now is the new Pardis Technology Park also focused on ICT (UNIDO, 2006b). Mexico also is actively developing technology parks, designed to attract multinational companies and promote the development of IT outsourcing services (Horowitz, 2003). OUTSOURCING: A NEW POSSIBILITY FOR RUSSIA? An aspiration of Russias IT and communications ministry and the software development community is to transform the country into a leading supplier of software to foreign customers, following the path of India in becoming a world center for the outsourcing of IT and business processes. However, the scale of Russias involvement in outsourcing lags far behind that of India and China, and it is difficult to see how Russia will be able to narrow the gap quickly. It is estimated that in 2004 Russias total software and services exports reached $750 million, rising to $994 mn in 2005, the main markets being the United States, Canada, Germany, and the Nordic countries (RUSSOFT/Outsourcing, 2006). This compares with 2004 offshored IT and business services amounting to $17.4 billion in India, and 2003 totals of $3.4 billion for China and $1.7 billion for the Philippines.22 One significant advantage enjoyed by both India and Philippines in business process and software outsourcing is a large, well-trained labor force with knowledge of English. There is no doubt that Russia possesses many talented software specialists, but they face problems. India now produces some 120,000 IT graduates a year and skills are being rapidly upgraded, but in Russia the total stock of programmers is some 200,000 and the labor force is growing considerably more slowly than in India (World Bank, 2005a; IKS-online, 2005). The salaries of Russian programmers are higher than in India, China, and other emerging economies that have become centers for outsourcing and it is not clear that this competitive disadvantage is offset by superior productivity. There is now mounting concern in Russia that rising salaries of programmers could lead to lost opportunities, and this concern has prompted demand for government action to subsidize the infrastructure costs of the software industry. In the

21April 4, 2006. At the same time, revealing a contradictory stance, Putin criticized the fact that about 80 percent of expressions of interest in working within the special zones had come from foreign companies, not Russian firms [http://ia.vpk.ru/cgi-bin/cis.cgi/News/View/167846], April 4, 2006. 22 The Indian total is derived from a Russian government briefing on the Indian economy [http://www. economy.gov.ru], February 8, 2006. The China and Philippines totals are derived from Mckinsey (2005, p. 13); the latter source gives $300 million as Russias equivalent 2003 total.

272

EURASIAN GEOGRAPHY AND ECONOMICS

software industry, labor costs can be 7080 percent of the total, but in Russia firms are disadvantaged by having to a pay the single social tax at a rate of 26 percent. The IT and communications ministry has been lobbying for a preferential 14 percent for IT companies.23 Indias software industry probably has superior managerial and entrepreneurial skills, partly because many managers have experience of working in the United States and other developed economies (Arora and Athere, 2000, p. 260). In Russia, the management model prevailing in the software business has been characterized by one informed observer as still Soviet in style (Shalmanov, 2004). Russian software firms also encounter obstacles that are typical of the Russian business environment. Whereas Indian firms developing software for new technology (for example, medical equipment) can import the hardware with a minimum of delay, it can take weeks in Russia to secure the necessary clearance through customs. New software developed in Russia has to be granted security clearance before it can be exported (Izvestiya, July 29, 2004).24 In short, Russian outsourcing lacks the flexibility and adaptability enjoyed by its competitors in India, China, and other countries. SECURITY POLICY AS AN OBSTACLE TO DEVELOPMENT OF THE KNOWLEDGE ECONOMY Further liberalization of telecommunications has been held back by the long delay in privatizing the sectors principal holding company, Svyazinvest, which controls seven regional telecom companies and the national long-distance operator Rostelecom. A major reason was the difficulty in meeting the demands of the military and security services, which insisted on guaranteed access to the companys networks after privatization; agreement was finally reached in February 2006 (Kremlin, 2005; RBC Daily, February 17, 2006). The development of digital broadcasting, in particular television, and Wi-Fi mobile technologies is hindered by the fact that in Russia only 9 percent of all available radio frequencies are allocated to civilian needs, the remaining 91 percent being reserved for the use of the military, security services, and government. According to Minister for IT and Communications, Leonid Reyman, about 70 percent of frequencies in Europe are for civilian purposes. In his view, digitalization in Russia will be delayed unless the Ministry of Defense frees frequencies for other uses. The Defense Minister, Sergey Ivanov, has shown willingness to cooperate, but it appears that no progress will be made before 2008 at the earliest, giving time for the military to modernize its equipment (Reiman, 2005, p. 1; Naumov, 2006). In addition, as noted above, security controls hinder the export of software. These security-related concerns are in part a legacy of Soviet times, but they put Russia at a disadvantage in attempting to move in the direction of a knowledge-based economy. PERFORMANCE IN EXPORTS AND HIGH TECHNOLOGY Confidence in Russias ability to make a transition to a knowledge-based growth strategy would be greater if the country now possessed a stronger capability in high-technology fields. Data on the share of high-technology goods in exports is not encouraging, as shown by Table 14. Further investigation reveals that most of Russias high-technology exports take the form of armaments, rather than civilian goods.

23For additional information, see [http://www.outsourcing-russia.com/docs/doc-1036], November 2005 and [http://www,outsourcing-russia.com/docs/?doc=1059], December 2005. 24In the words of new-economy specialists of the Higher School of Economics, the procedure for obtaining permission to export software has been complicated to the point of absurdity (Kuzminov et al., 2003, p. 9).

JULIAN COOPER

273

Table 14. Exports of High-Technology Goods, 2003

Value of high-technology exports (mill. $) 4,505 107,543 9 2,292 4,580 51 28,634 23,942 5,327 815 145 160,212 Hi-tech exports as percentage of total exports of manufactures 12 27 5 14 2 21 74 19 2 2 31 Hi-tech exports as percentage of total exports 6.2 24.6 3.9 7.3 0.2 17.0 66.6 4.0 1.7 0.7 24.8

Country

Brazil China Egypt India Indonesia Iran Mexico Philippines Russia Turkey Vietnam U.S.

Source: Compiled by the author from UNDP, 2005 and World Bank, 2005c.

The comparative position of Russia can be illuminated further by examining the Balassa index of revealed comparative advantage (RCA) for selected high- and medium-technology goods. While this measure has well-known limitations for cross-country comparisons, it can nevertheless provide an instructive snapshot of a countys relative standing at a particular point in time. A good has RCA if the index is greater than 1, and revealed comparative disadvantage if less than 1. Results for 2004 are shown in Table 15. As can be seen, Russias performance in most sectors is not impressive, and compares unfavorably with Brazil, China, Mexico, and Turkey. For certain goods Indias RCA indices are superior. Some of the impressive achievements of comparator countries, notably of China, depend to a large extent on the activities of foreign companies and involve substantial imports of components. However, this raises the question of why Russia has not followed the same path. Examination of Russias export performance in greater detail reveals that there are some 70 product groups at the 4-digit SITC-3 level for which there is RCA. However, almost all products comprise hydrocarbons, metals, minerals, chemicals, and timber, often at a low level of processing. Only four machine-building product groups appear and these mainly relate to Soviet legacies such as fuel elements for Soviet-built nuclear power stations, rail freight cars (imported by CIS and Baltic countries having Soviet wide-gauge tracks), and equipment for nuclear power stations being built by Russia in such countries as China, India, and Iran. There are no explicit data for arms exports, but there is a substantial group of unclassified goods for which there is RCA, which may include combat aircraft and some other systems in which Russia probably has an advantage.25

25Russias competitive strengths and weaknesses as revealed by RCA are considered in more detail in a forthcoming paper by the author in Eurasian Geography and Economics (Cooper, 2006).

274

Table 15. Revealed Comparative Advantage Index, 2004a

EGY IRNb 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 . 0.01 0.03 0.01 0.34 1.99 2.19 1.03 3.44 3.48 0.37 0.06 1.17 2.87 0.24 4.32 3.44 1.28 0.09 0.12 0.09 0.02 0.03 0.07 0.01 0.02 0.05 0.06 0.22 0.04 0.21 0.12 0.14 0.32 0.06 0.10 0.04 0.08 0.93 0.05 0.10 0.11 0.53 0.16 1.56 0.57 1.16 0.98 0.12 MEX PHL RUS TUR 0.04 0.04 0.09 0.06 0.01 0.03 0.07 0.07 0.06 0.06 0.15 0.23 0.40 0.16 0.93 0.06 0.17 0.43 0.81 0.30 0.81 0.69 0.03 0.08 1.46 0.06 0.02 0.05 0.04 0.52 0.07 IND IDN VNMb 0.12 0.26 0.21 0.06 0.19 0.90 0.01 0.03 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.02 USA 1.13 0.71 0.85 2.15 2.07 0.98 1.25 1.27 3.67 0.48 1.32 1.77

SITC code 0.69 2.38 2.16 0.33 0.37 1.32 0.27 0.14 0.07 0.01 0.19 0.67

Product group

BRA

CHN

776 752 764 874 872 716 731 720 792 781 713 541

Electronic components Computer equipment Telecoms equipment Measuring-control apparatus Medical instruments Rotating electric plant Metal-cutting macchine tools Tractors Civil aircraft, spacecraft Passenger cars Internal combustion engines Pharmaceuticals

0.06 0.32 0.38 0.15 0.20 0.94 0.31 3.41 2.64 0.66 1.79 0.23

aFor

EURASIAN GEOGRAPHY AND ECONOMICS

selected medium- and high-technology fields. The SITC, Rev.3 trade classification was employed, here at the three-digit level. 2003. Sources: Calculated by the author from data of the Commodity Trade Statistics Database (UN Comtrade, n.d.).

bFor

JULIAN COOPER

275

Some comparator countries have been able to develop competitive, relatively high technology, sectors enjoying considerable export success. The Brazilian aircraft industry provides a good example: Embraer is a leading supplier of regional/commuter jets and this represents a successful niche activity in a high-technology sphere, providing an interesting case study of created comparative advantage. This success owes much to the creation of a local system of innovation in the So Jos dos Campos region, the development of an international production chain, and the fostering of conditions conducive to a build-up of local R&D, technological, and manufacturing capabilities. In this sector of the aviation industry, Brazil now occupies a position that no Russian firm is likely to challenge in the foreseeable future, notwithstanding Russias substantial, long-standing, involvement in the building of aircraft.26 As Rodrik (2006) has shown, China, strikingly, but also India, Mexico, and Turkey, have been able to develop export profiles skewed toward high-productivity goods to an extent greater than normally would be expected given their income levels. Russias performance is not discussed by Rodrik, but the evidence considered above suggests that it has failed to develop an export profile similar to that of the most dynamic emerging economies (ibid.). In Rodriks view, a major factor in Chinas success has been the openness to foreign investment in forms that have promoted the development of domestic capabilities: The large size of the economy has allowed policy experimentation. It also has allowed the government to use the carrot of the internal market to force foreign investors into joint ventures with domestic producers (Rodrick, 2006, p. 22). Perhaps because the domestic market is smaller, Russia has not had the same success. However, in the authors view the explanation probably lies more in attitudes: Russia simply has not seen the necessity of learning from foreign experience in the same way that China and other emerging economies have. As shown in Table 16 (based on UNCTAD, n.d.), the stock of Russias foreign direct investment (FDI) in per capita terms is quite respectable, but the FDI inflow in 2004 was more modest than that in China, Brazil, and Mexico, and biased toward the energy sector, with relatively modest investment in the manufacturing sector. However, there are now signs that in some sectors Russia is beginning to adopt a policy resembling that pursued by China. In the automobile, tractor, and agricultural machine-building industries, foreign companies are being encouraged to establish assembly plants in Russia, and are expected to sign agreements to increase domestic content over a number of years. It is not without irony that some of the early interest in these new possibilities has come from Chinese and Indian vehiclebuilding companies, and there has also been discussion of building one of the Brazilian Embraer family of regional jets in Russia.27 COMPETITIVENESS In assessing Russias performance in moving toward a knowledge economy, the economic environment cannot be ignored. The evidence suggests that in one important respect Russia has a disadvantage. When compared with comparator countries, the economy turns

an insightful analysis, see Cassioloato et al. (2002). the Chinese Great Wall company is interested in assembling its Hover jeeps in Tatarstan and Chery Automobile is considering assembly in Novosibirsk. The Indian company Mahindra intends to assemble its Scorpio off-road vehicle in Russia (for details, see http://www.wto.ru/press.asp?msg_id=15746, March 17, 2006; Kommersant Daily, April 7, 2006, p. 14).

27Thus 26For

276

EURASIAN GEOGRAPHY AND ECONOMICS

Table 16. Inward Foreign Direct Investment in 2004 (in mill. dollars)

Country Brazil China Egypt India Indonesia Iran Mexico Philippines Russiaa Turkey Vietnam U.S. FDI stock 150,965 245,467 20,902 38,676 11,352 4,065 182,536 12,685 98,444 25,188 29,115 1,473,860 FDI inflow 18,166 60,630 1,253 5,333 1,023 500 16,602 469 11,672 2,733 1,610 95,859 FDI stock per capita 836 189 299 4 51 58 1,740 153 683 348 353 5,022

aIn 2004, FDI outward stock was $81,874 million and outflow $9,601 million. For other countries (excluding the United States and Brazil), FDI outflows are modest in comparison with inflows.

out to be not very competitive. This is shown by a number of international rankings. Table 17 presents the assessment of the World Economic Forum (WEF, 2005).28 According to this assessment, Russia is one of the least competitive economies of the group. Whereas India has moved steadily up the ranking in recent years and Chinas position has slightly deteriorated, Russia has dropped five places since 2003. The ranking suggests that problems are most severe at the micro-level. ASSESSING KNOWLEDGE-ECONOMY READINESS A useful benchmarking tool for assessing the readiness of countries for the knowledge economy is the Knowledge Assessment Methodology (KAM) developed by the World Bank Institute (World Bank, 2006b). The KAM basic scorecard summarizes sets of variables characterizing performance in terms of four pillars of the knowledge economy: (1) the education and skills of the labor force; (2) the effectiveness of the innovation system; (3) the adequacy of the ICT infrastructure; and (4) the extent to which the economic and institutional regime is conducive to the creation and use of knowledge. A total of 80 variables are employed. The variables are normalized from 0 (weakest) to 10 (strongest), and the 128 countries covered by the KAM are ranked on an ordinal scale. The overall performance of countries is summarized by a more narrowly based Knowledge Economy Index (KEI), which can be used to show trends over time (e.g., see Chen and Dahlman, 2005). Recognizing that performance in innovation may depend on a country possessing a critical mass of researchers giving rise to economies of scale in knowledge production, the main innovation variables are presented as either unweighted or weighted, the former taking absolute values and the latter weighted by a

28Russias position is assessed somewhat more favourably in the annual ranking of the International Institute of Management Development, Lausanne, but this World Competitiveness Scoreboard covers only 60 countries. In 2005 Russia was ranked 54, compared with rankings of 32 for China, 39 for India, and 51 for Brazil (IMD, 2005).

JULIAN COOPER

277

Table 17. World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness and Business Competitiveness Indices, 20052006a

Country Brazil China Egypt India Indonesia Mexico Philippines Russia Turkey Vietnam U.S. GC Overall 65 49 53 50 74 55 77 75 66 81 2 Inc. tech.b 50 64 58 55 66 57 54 73 53 92 1 BCI 49 57 71 31 58 60 69 74 51 80 1

aN = 117. Iran not included in the index. GCI = quality of macroeconomic environment, state of countrys public institutions, and level of technological readiness; BCI = underlying microeconomic factors, includes company operations and strategy and quality of national business environment. bTechnology index.

Table 18. World Bank Knowledge Economy Index (KEI), 20032004a

Country Brazil China Egypt India Indonesia Iran Mexico Philippines Russia Turkey Vietnam U.S. Rank 40 56 70 79 77 82 45 59 37 52 90 5 KEI 5.83 5.01 4.19 3.81 3.90 3.60 5.58 4.82 6.39 5.26 3.08 8.62 EIR 5.08 2.95 3.13 2.47 3.65 2.71 4.89 4.59 3.01 4.50 2.03 7.61 Innovation 8.08 9.18 5.77 8.66 5.75 4.71 7.49 5.35 8.81 7.00 3.40 9.91 Education 5.59 3.60 4.51 2.16 3.34 3.71 4.37 5.34 7.85 4.19 3.99 8.22 Info. inf. 5.64 4.30 3.35 1.96 2.58 3.26 5.58 3.98 5.88 5.35 2.88 8.74

aN = 128; KEI = knowledge economy index; EIR = economic incentive regime; Info. inf. = information infrastructure (ICT).

countrys population. This is important when considering populous countries such as China and India, for example, as they have a critical mass of innovative capacity that is not reflected when scaled by population. For this reason only unweighted variables are used here. The most recent, 20032004, KEI are shown in Table 18.

278

EURASIAN GEOGRAPHY AND ECONOMICS

Table 19. Knowledge Economy Index, 1995 and Most Recent, 20032004 (unweighted)a

Country Brazil China Egypt India Indonesia Iran Mexico Philippines Russia Turkey Vietnam U.S.

aN bInfo.

KEI rank 1995 54 72 71 71 75 82 43 64 35 47 102 1 Latest 40 56 70 79 77 82 45 59 37 52 90 5 1995 5.30 4.07 4.23 4.03 3.80 3.44 5.72 4.68 6.29 5.60 2.01 9.21

KEI Latest 5.83 5.01 4.19 3.81 3.90 3.60 5.58 4.82 6.39 5.26 3.08 8.62

Innovation 1995 7.87 8.81 6.43 8.48 5.45 5.41 7.28 5.37 9.09 6.38 2.01 9.90 Latest 8.08 9.18 5.77 8.66 5.75 4.71 7.49 5.35 8.81 7.00 3.40 9.91

Info. infrastr.b 1995 5.30 1.68 3.45 2.40 3.16 3.54 5.52 3.69 5.95 5.68 1.10 9.74 Latest 5.64 4.30 3.35 1.96 2.85 3.26 5.58 3.98 5.88 5.35 2.88 8.74

= 128. Inf. = information infrastructure.

Russias position is relatively strong, but to a large extent this is because of the variables used to assess educational attainmentadult literacy and enrollment at the secondary and tertiary levels. However, Brazil and Mexico are not far behind, and Turkey and China are also quite strongly placed. In terms of the KEI, Iran and Vietnam have considerable ground to make up, and Indias performance is weakened by relatively weak educational attainment and ICT diffusion. Using the KAM, it is instructive to examine changes occurring over time, comparing performance in 1995 with the latest data (20032004). Table 19 shows performance summarized by the KEI and by two of its componentsinnovation and information infrastructure. Over the period, Russias ranking fell slightly, and the decline would have been greater if there had not been an improvement in the economic incentive regime, the score for which rose from 2.33 to 3.01. Countries rising rapidly up the ranking are China, Brazil, and Vietnam, with the Philippines also showing better performance. Less impressive are India, Indonesia, Mexico, and Turkey. If present trends are maintained, Russia is in danger of being overtaken by countries with more rapidly improving knowledge-economy characteristics. CONCLUSION The Russian economy has been growing for five years at a relatively high rate of almost 7 percent, but examination of future prospects in comparative terms suggests that the prospects are not so good. China is rapidly narrowing the gap, and there are other emergent countries of comparable or lower levels of per capita income that now appear to have the potential to rival Russias economic strength during the next 1015 years. In particular, one can single out Mexico, Brazil, and Turkey, and, taking a longer view, it is probably a mistake to discount completely the possibilities of Indonesia and Vietnam. The evidence reviewed above suggests that Egypt and Iran will not represent serious competition, the latter sharing some characteristics with Russia, in particular an economy dominated by the minerals sector

JULIAN COOPER

279

with substantial state involvement in economic life. In the authors view the economists of Goldman Sachs are excessively optimistic in relation to Russias growth prospects, understating the impact of unfavorable demographic trends and structural factors that are likely to complicate diversification and transition to a more knowledge-based path of development. That the policy dimension may have been understated has been hinted by Jim ONeill, head of the Global Economic Research division of Goldman Sachs, responsible for the BRICs acronym. Speaking at the Davos World Economic Forum in January 2006, he acknowledged that of the four countries it was Russia that worried him most. In ONeills words, The motives for the decisions coming out of the Kremlin are difficult for us to understand, although they are not always sinister (quoted in Berry, 2006). As noted at the outset, Russia is unique in the group of countries discussed in this paper, in having undergone a difficult process of partial de-development during the last 15 years. The Russian people and the political elite are having to adapt to a reduced role in the world for their country: not long ago a superpower, often compared with the United States, but now a relatively weak emerging economy with much reduced global influence. From the outset, it has been clear that for President Putin restoration of the great power status of Russia has been a central strategic goal. But the Soviet legacy remains strong and casts a shadow over the present, not least in its influence on attitudes and practices. Most of the other populous emerging economies could be characterized as aspiring nations, focused on securing better economic futures and, as such, open to new ideas and to learning from the more developed world. In contrast, Russia, having been strong and self-reliant, gives the impression of being much less disposed to learn from others, and resentment rather than aspiration appears to be the dominant mood. Russias development as a more knowledge-based economy is also hampered by its security orientation and practices inherited from Soviet times, and given new impetus by the political elites perception that the country is insecure and that its sovereignty is under threat.29 In this respect, the prospects for Russia are at present not so favorable. In some fields, however, Russia has been relatively successful. The development of the Internet has proceeded at a respectable pace and mobile phones have rapidly diffused. In both cases, the state has played little role and the momentum has derived from individual initiative. It does appear that, in the case of Russia, the more the state is involved in knowledgeeconomy activities, the less impressive are the results. This is shown clearly in the sphere of R&D, which is still dominated by state-owned facilities, including those of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and threatens to be shown yet again in the case of the state-initiated creation of special economic zones. Russias dilemma has been summarized by Boris Saltykov: Its time to stop comparing ourselves all the time with the USA, high time! Let us find our own place in this world! There is an excellent summary model of the global innovation system, he continues, in America they invent, in China they produce, in India they program, in Europe they consume, Africa rests. And where in this is the place for Russia?, Saltykov ponders. We need to find it, because in Russia there is a little bit of that, a little bit of the other. Noting the fact that Russians are a creative people, who love complex and unique tasks, he believes that the solution lies in integration with the worlds leading high-technology companies. In the process, Russia will find niches to occupy, but in Saltykovs view a basic precondition for this outcome is radical reform of the economys state sector (Saltykov, 2005).

29This view has been voiced in explicit terms by Vladislav Surkov, deputy head of Putins administration (see Suverinitet, 2006).

280

EURASIAN GEOGRAPHY AND ECONOMICS

A distinctive feature of the Russian economy, distinguishing it from almost all comparator emerging economies, is its rich endowment with hydrocarbons, minerals, and other primary products. This resource wealth, coupled with sound macroeconomic management, has secured its impressive growth over the past few years. Perhaps an answer to the question of Russias place in the world can be found in a policy of concerted application of knowledge to the goal of achieving the best possible economic outcomes from the fundamental comparative advantage the country enjoys.30 This could still represent a knowledge-based economy, but one adapted to Russias specific circumstances. REFERENCES

Arora, Ashish and Suma Athreye, The Software Industry and Indias Economic Development, Information Economics and Policy, 14, 2:253-273, 2000. Berry, Lynn, Investors Find Only Gref at Davos, The Moscow Times [http://www.moscowtimes.ru/ stories/2006/ 01 /27/ 001.html], January 27, 2006. Cassioloato, Jos E., Roberto Bernardes, and Helena Lastres, Transfer of Technology for Successful Integration into the Global Economy: A Case Study of Embraer in Brazil. New York, NY and Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, UNCTAD/ITE/IPC/ Misc. 20, 2002. Cell Phones in Egypt, [http://www.cellular-news.com/coverage/egypt.php], n.d. Chen, Derek H. C. and Carl J. Dahlman, The Knowledge Economy, KAM Methodology, and World Bank Operations, [http://siteresources.worldbank.org], October 2005. China Internet Information Center, [http://service.chain.org.cn], citing Xinhua News Agency, February 9, 2006a. China Internet Information Center, [http://service.china.org.cn], citing Xinhua News Agency, March 1, 2006b. China Internet Information Center, China Hikes Sci-tech Input by 19.2%, [http://www.china. org.cn/english/scitech/160337.htm], from Peoples Daily, March 6, 2006c. China Tops Cellular Subscriber Top 15 Ranking. Cellular Subscribers Will Top 2B in 2005, Computer Industry Almanac, [http://www.c-i-a.com/pr0905.htm], September 26, 2005. Cooper, Julian, Can Russia Compete in the Global Economy, Apart from Energy?, Eurasian Geography and Economics, 47, 2006 (forthcoming). Dahlman, Carl J. and Jean-Eric Aubert, China and the Knowledge Economy. Seizing the 21st Century. Washington, DC: World Bank, WDI Development Studies, 2001. Dezhina, Irina, Russian Scientists: Where Are They? Where Are They Going? Human Resource and Research Policy in Russia. Paris, France: Institut Francais des Relations Internationales, Russia.Cei.Visions, no. 4, June 2005, 15 pp. Dezhina, I. G., and B. G. Saltykov, The National Innovation System in the Making and the Development of Small Business in Russia, Studies on Russian Economic Development, 16, 2:184-186, 2005. Dezhina, I. G. and S. V. Yegerev, Kak pomoch kadrovoy reabilitatsii Rossiyskoy nauki (How to Assist the Rehabilitation of Personnel in Russian Science), [http://www.fondedin.ru/dok/ dezh.pdf], 2005. Dvorkovich, Arkadiy, Yesli otsenivat po pyatballnoy shkaletri s minusom. No eto shag po sraveniyu s dva s minusom tri-cheterye goda nazad (If Evaluated on a Five-Point ScaleThree Minus. But This Is a Step Forward Compared to a Two Minus Three to Four Years Ago), [http://www.opec.ru], March 2, 2006.

30This option of harnessing science to the materials sector is occasionally acknowlegded by Russian economists (e.g., Yudayeva, 2005, p. 65). Yudayeva argues that Russia has little choice but to remain a major exporter of energy and other mineral resources, and that this is not necessarily a negative path.

JULIAN COOPER

281