Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Marshak V Schaffner Marvelettes

Caricato da

mschwimmerTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Marshak V Schaffner Marvelettes

Caricato da

mschwimmerCopyright:

Formati disponibili

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK -------------------------------------- X : LARRY MARSHAK, : Plaintiff, : : -v: : KATHERINE SCHAFFNER,

et al., : Defendants. : : -------------------------------------- X APPEARANCES: For the plaintiff: Samantha Morrissey William Dunnegan Dunnegan & Scileppi LLC 350 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10118 For the defendants: Kerren B. Zinner Andrew B. Messite Pamela L. Schoenberg Reed Smith LLP 599 Lexington Avenue New York, NY 10022

11 CIV. 1104 (DLC) OPINION & ORDER

DENISE COTE, District Judge: On January 17, 2012, plaintiff Larry Marshak (Marshak) and defendants Katherine Schaffner (Schaffner) and the Estate of Gladys Horton (Horton) cross-moved for summary judgment. This Opinion addresses the parties cross-motions for summary judgment on Marshaks false designation of origin claim.

1

For

the following reasons, the defendants motion for summary judgment on Marshaks false designation of origin claim is granted, while Marshaks motion for summary judgment on his false designation of origin claim is denied.

Background The following facts are undisputed, unless otherwise noted. In 1961, Motown Records Corporation (Motown) had one of its first major hits with the song Please Mr. Postman, recorded by a new singing group called The Marvelettes.1 The group began

life as the Cant Sing Yets, five high school girls from Inkster, Michigan, including Schaffner, Horton, Georgia Dobbins (Dobbins), Juanita Cowart (Cowart), and Georgeanna Tillman (Tillman). According to Schaffner, after the Cant Sing Yets

performed at an Inkster High School talent show in early 1961, a teacher arranged a Motown audition for the group in Detroit. The group impressed Motown executives at the audition, who instructed the girls to return with an original song to perform. In response, Dobbins wrote Please Mr. Postman. After hearing

the group perform the song, Motown offered to sign the group to a recording contract.

1

Unless otherwise indicated, this Opinion will use the term The Marvelettes to refer to the original singing group that recorded and performed between 1961 and 1969, and whose members included Schaffner and Horton.

2

First, however, the group needed a new name.

According to

Schaffner, Dobbins suggested The Marvels, which Motown executive Berry Gordy changed to The Marvelettes. Each member

of the group was then required to sign, along with a guardian, a Motown recording contract. Because Dobbins father refused to

sign the contract, Dobbins was replaced in the group by Wanda Young (Young). On July 1, 1961, Schaffner and Horton both signed recording contracts with Motown (the Contracts). The Contracts provide

for royalty payments to the Marvelettes members based on percentage revenues of records sold. groups name, the Contracts state: The collective name of the group is THE MARVELETTES. We shall have all of the same rights in the collective name that we have to use your name pursuant to paragraph 6 and you shall not use the group name except subject to the restrictions set forth in that paragraph. In the event that you withdraw from the group, or, for any reason cease to participate in its live or recorded performances, you shall have no further right to use the group name for any purpose. Paragraph six of the Contracts provides, in relevant part, that Motown shall have the right . . . to sell and deal [records and other reproductions of performances] under any trademarks or trade-names or labels designated by us[.] The Contracts With respect to the

provide for four-year terms, and Horton and Schaffner signed

follow-up agreements containing substantially similar language bearing on trademark rights in early 1965. The Marvelettes continued to record for Motown and perform in live concerts through the 1960s. While the group

consistently had between two and five performers during this period, its composition changed. the group: Three original members left

Cowart in 1962, Tillman in 1965, and Horton in 1967. The

Ann Bogan replaced Horton in The Marvelettes in 1967.

group, its final iteration comprising Schaffner, Young, and Bogan, disbanded in 1969.2 Music recorded by The Marvelettes continues to be sold commercially and receive radio play. Original members of The

Marvelettes, including Schaffner and, until her death in 2011, Horton, receive royalty payments for radio play and song and album sales of The Marvelettes recordings. receives royalty payments. Hortons estate now

The payments are made by Motowns

successor-in-interest, UMG Recordings, Inc. (UMG). During the late 1960s, Marshak, an editor at Rock Magazine, booked The Marvelettes for performances. At his deposition,

Marshak testified that booking groups involved the following process:

2

You call up the group, and you say you want to work

According to both Schaffner and Vaughn Thornton (Thornton), Hortons son, Horton left the group in 1967 to care for her new child. Schaffner states that after the group disbanded in 1969, she had no plans to continue recording or performing.

4

or do XYZ performance, XYZ date, enter into a contract, and they perform it. According to Marshak, he originally began using the mark The Marvellettes3 for groups staging live performances under his production and management in the 1970s. Marshaks groups do

not include any of the members of The Marvelettes who recorded music for Motown. As Marshak described it at his deposition,

sometime in the early 1970s Ewart Abner, Motowns president, told Marshak that The Marvelettes were no longer recording or performing. Marshak has had as many as three groups performing under the name The Marvellettes at a given time. At present,

Marshak has one Marvellettes group performing in Las Vegas. Marshaks Marvellettes perform Motown songs, including songs originally recorded by The Marvelettes. Marshaks groups have

always consisted of three female members, the ages of whom tend to correspond with the contemporary ages of the original members of The Marvelettes. The groups are advertised to the public as

The Marvellettes, and at no time during a show are audience

Marshak uses a version of the mark that includes an extra l. In their papers, the defendants refer to the mark as The Marvelettes, while Marshak refers to the mark as The Marvellettes. Neither party attempts to argue that the difference in spelling should affect analysis of the parties claims. For simplicitys sake, this Opinion will use the original one-l spelling.

5

members told that the performers were not members of The Marvelettes group that recorded for Motown in the 1960s. On December 27, 1976, Marshak applied for registration of the service mark The Marvellettes with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) for use in connection with musical entertainment services rendered by a vocal and instrumental group. The application was unopposed; on January

3, 1978, the mark was registered by the PTO, with Marshak listed as owner. Over the ensuing years, Horton made a number of attempts to return to the stage, and sought to use the mark in promoting her performances. According to Marshak, he threatened litigation

when Horton sought to use the mark The Marvelettes in connection with a New Years Eve performance she booked in 1994. On December 14, 1994, Marshak and Horton entered an agreement to settle Marshaks claims. Horton agreed to the entry of an order of permanent injunction . . . enjoining her . . . from representing . . . that she has the right to use the name or mark, THE MARVELLETTES, to identify any musical performing group other than the musical performing group controlled by Larry Marshak . . . . The agreement further provided that Marshak would refrain from representing . . . that [Horton] does not have the right to use Under the terms of the agreement,

the name or marks GLADYS HORTON FORMERLY OF THE MARVELLETTES to identify [Horton] and her musical performing group. Marshaks PTO registration for the mark THE MARVELLETTES lapsed in 2008. On August 19, 2008, Schaffner and Horton filed

a joint application with the PTO to register the mark THE MARVELETTES for use in connection with [e]ntertainment services in the nature of a musical and vocal recording and performing group.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY On February 17, 2011, Marshak filed his complaint in this action, alleging, inter alia, false designation of origin in violation of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. 1125(a). Marshak On

sought injunctive and declaratory relief as well as damages.4 May 9, the defendants filed their answer, including counterclaims alleging false designation of origin, trademark

dilution and tarnishment, common law trademark infringement, and deceptive acts and practices in violation of New York General Business Law 349. Marshak filed a reply to the defendants

counterclaims on May 27.

In their moving papers, the defendants state that Marshak has abandoned his claims for trademark infringement and unfair competition and any other claim for damages. Marshak does not dispute this assertion.

7

The parties cross-moved for summary judgment on January 17, 2012. The cross motions affect all remaining claims in the The motions became fully submitted on February 14. As

action.

noted, this Opinion addresses the cross-motions for summary judgment on Marshaks false designation of origin claim only.

DISCUSSION Summary judgment may not be granted unless all of the submissions taken together show that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and that the movant is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. Fed. R. Civ. P. 56(c). The

moving party bears the burden of demonstrating the absence of a material factual question, and in making this determination, the court must view all facts in the light most favorable to the nonmoving party. Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317, 323

(1986); see also Holcomb v. Iona Coll., 521 F.3d 130, 132 (2d Cir. 2008). Once the moving party has asserted facts showing that the non-movant's claims cannot be sustained, the opposing party must set out specific facts showing a genuine issue for trial, and cannot rely merely on allegations or denials contained in the pleadings. Fed. R. Civ. P. 56(e); see also Wright v. Goord, 554 A party may not rely on mere

8

F.3d 255, 266 (2d Cir. 2009).

speculation or conjecture as to the true nature of the facts to overcome a motion for summary judgment, as [m]ere conclusory allegations or denials cannot by themselves create a genuine issue of material fact where none would otherwise exist. Hicks

v. Baines, 593 F.3d 159, 166 (2d Cir. 2010) (citation omitted). Only disputes over material facts -- facts that might affect the outcome of the suit under the governing law -- will properly preclude the entry of summary judgment. Anderson v.

Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 248 (1986); see also Matsushita Elec. Indus. Co., Ltd. v. Zenith Radio Corp., 475 U.S. 574, 586 (1986) (stating that the nonmoving party must do more than simply show that there is some metaphysical doubt as to the material facts). The parties have cross-moved for summary judgment on Marshaks false designation of origin claim. The crux of the

parties dispute is whether Marshak acquired common law trademark rights in the mark The Marvelettes. Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act imposes civil liability on [a]ny person who, on or in connection with any goods or services . . . uses in commerce any word, term, name, symbol, or device, or any combination thereof, or any false designation of origin, false or misleading description of fact, or false or misleading representation of fact, which(A) is likely to cause confusion, or to cause mistake, or to deceive as to the affiliation, connection, or association of such person with another person, or as

9

to the origin, sponsorship, or approval of his or her goods, services, or commercial activities by another person[.]

15 U.S.C. 1125(a)(1)(A).

To succeed on a Section 43(a) claim,

a plaintiff must establish both (1) that its trademark is entitled to protection and (2) that the defendant's mark is likely to confuse consumers as to the origin or sponsorship of its product. Virgin Enters., Ltd. v. Nawab, 335 F.3d 141, 146

(2d Cir. 2003). As both parties effectively agree, the success of Marshaks claim depends upon his showing that he owns trademark rights in the mark The Marvelettes. Marshak stakes his claim of

ownership on common law trademark rights in the mark that he maintains he has acquired through continuous use since the 1970s.5 But, Marshak could not have acquired common law rights It is undisputed that a senior

in the mark The Marvelettes.

user owned the rights in the mark; that senior user did not abandon those rights and accordingly still owns them. false designation of origin claim therefore fails. Marshaks

In his deposition, Marshak discussed a purported assignment of rights in the mark that he claims he received from Motown sometime in the early 1970s. Marshak has been unable to produce a copy of the assignment or testimony of any other witness with first-hand knowledge of the assignment. Marshak does not rely upon the purported assignment either in his own summary judgment moving papers or in opposing the defendants summary judgment motion.

10

Because a trademark represents the reputation developed by its owner for the nature and quality of goods or services sold by him, he is entitled to prevent others from using the mark to describe their own goods. Defiance Button Machine Co. v. C & C The

Metal Products Corp., 759 F.2d 1053, 1059 (2d Cir. 1985). Lanham Acts protection extends to unregistered, common law trademarks.

Time, Inc. v. Peterson Publishing Co., L.L.C., 173 Common law [t]rademark rights

F.3d 113, 117 (2d Cir. 1999).

develop when goods bearing the mark are placed in the market and followed by continuous commercial utilization. Buti v. Perosa,

S.R.L., 139 F.3d 98, 103 (2d Cir. 1998) (citation omitted). It is a matter of first principles that for inherently distinctive marks, ownership is governed by priority of use. For such marks, the first to use a designation as a mark in the sale of goods or services is the owner and the senior user. McCarthy on Trademarks and Unfair Competition 16:4 (4th ed. 2012).6 The user who first appropriates the mark obtains [an]

enforceable right to exclude others from using it, as long as the initial appropriation and use are accompanied by an intention to continue exploiting the mark commercially. La

Societe Anonyme des Parfums le Galion v. Jean Patou, Inc., 495 F.2d 1265, 1271 (2d Cir. 1974). Accordingly, a junior user

It is undisputed that The Marvelettes is a distinctive mark.

11

cannot develop common law rights in a mark where a senior user already owns those rights and has not abandoned them. v. Punchgini, Inc., 482 F.3d 135, 147 (2d Cir. 2007). If an owner ceases to use a mark without an intent to resume use in the reasonably foreseeable future, the mark is said to have been abandoned. Id. An abandoned mark returns See ITC

to the public domain and may, in principle, be appropriated for use by other actors in the marketplace, in accordance with the basic rules of trademark priority. Id. (citation omitted). A

party asserting abandonment must demonstrate (1) non-use of the mark by the legal owner, and (2) lack of intent by that owner to resume use of the mark in the reasonably foreseeable future. Id. (citing 15 U.S.C. 1127). Rights in a mark signifying a singing group are not abandoned by the owner upon the groups disbandment, so long as the owner continues to receive royalties from the sale of the groups previously recorded material. [A] successful music

group does not abandon its mark unless there is proof that the owner ceased to commercially exploit the marks secondary meaning in the music industry. Marshak v. Treadwell, 240 F.3d Accord The Kingsmen

184, 199 (3d Cir. 2001) (citation omitted).

v. K-Tel Intl, Ltd., 557 F.Supp. 178, 183 (S.D.N.Y. 1983) (members of The Kingsmen continued to receive royalties).

12

The

continuous use of the mark in connection with the commercial exploitation of [a] groups recordings in this country g[ives] rise to a strong inference of an intent not to abandon the mark. Treadwell, 240 F.3d at 199.

The defendants are entitled to judgment as a matter of law on Marshaks false designation of origin claim. Simply put,

Marshak cannot establish ownership rights in the mark because a senior user owned those rights prior to Marshaks first use of the mark to promote live musical performances, and that senior user has not abandoned the mark.

7

It is undisputed that a senior user established trademark rights in The Marvelettes prior to Marshaks first commercial use of the mark in the early 1970s.8 Under traditional priority

of use principles, the owner of The Marvelettes retains the right to exclude others from using the mark, preventing others from developing common law rights in the mark, unless the owner abandoned the mark. abandoned. owner.

7

The mark The Marvelettes has not been

To the contrary, it remains in use by its legal

UMG, Motowns successor, continues to sell recordings by

It is not necessary for purposes of deciding the cross-motions for summary judgment on Marshaks false designation claim to determine whether the members of The Marvelettes or Motown own rights in the mark.

8

Indeed, in his summary judgment moving papers Marshak asserts that Motown owned the mark during the 1960s.

13

The Marvelettes under the mark, and continues to license the groups music for radio play. Shaffner and Hortons estate

continue to receive royalties for both sales of recordings and radio plays. The continued exploitation of the marks secondary

meaning through record sales and radio play demonstrates both use of and an intent not to abandon the mark. Because Marshak bases his purported ownership of the mark on common law rights, he must demonstrate the senior users abandonment of the mark.9 This he cannot do.

First, Marshak argues that while Motown owns the rights to use the mark in connection with the sale of recorded performances, Motown abandoned its use of the mark in connection with live musical performances. In essence, Marshak argues that

a single mark may be used to designate recorded performances of one origin and live performances of an entirely different origin. Marshak is wrong, as a matter of trademark first principles. As the Court of Appeals explained in another case

involving Marshaks efforts to claim trademarks associated with vintage recording groups, [a] trade name or mark is merely a

In his briefing of the cross-motions, Marshak disclaims any reliance upon the purported assignment of rights from Motown or upon his lapsed PTO registration of the mark The Marvellettes. He relies instead exclusively upon his alleged common law rights in the mark.

14

symbol of goodwill; it has no independent significance apart from the goodwill it symbolizes. 927, 929 (2d Cir. 1984). Marshak v. Green, 746 F.2d

For that reason, [u]se of the mark .

. . in connection with a different goodwill and different product would result in a fraud on the purchasing public who reasonably assume that the mark signifies the same thing, whether used by one person or another. Id. In Green, the

court held that the transfer of the trademark Vito and the Salutations to Marshak would be a transfer devoid of the trademarks associated goodwill: Entertainment services are unique to the performers. Moreover, there is neither continuity of management nor quality and style of music. If another group advertised themselves as VITO AND THE SALUTATIONS, the public could be confused into thinking that they were about to watch the group identified by the registered trade name. Id. at 930. Basic principles of consumer protection embedded in the trademark laws explain why Marshak cannot own the rights to The Marvelettes for use in live performances while Motown (and/or members of The Marvelettes) continues to own the rights in connection with marketing recordings. Both uses of the mark The

draw upon the same source of consumer goodwill:

Marvelettes original recordings and performances during the 1960s. Moreover, Marshak quite clearly trades upon the consumer

15

goodwill associated with the original groups use of the mark. His Marvellettes perform songs recorded by the original Marvelettes, and throughout the years Marshak has presented performers of approximately the same age as the contemporary age of the original Marvelettes. Marshak makes no effort to alert

potential audience members that his performers are not members of the original group. To the contrary, Marshaks presentation

of live performances under the mark encourages potential audience members to believe that they are paying to see the original group whose recordings continue to be sold and receive radio play, rather than a tribute band. The danger of consumer

confusion and deception is manifest, and indeed, has almost certainly been realized in this case. Marshaks argument that

he owns the mark for live performances while Motown owns it for musical recordings must fail. Marshak cites to Bell v. Streetwise Records, Ltd., 761 F.2d 67 (1st Cir. 1985), to argue that trademark rights in musical recordings and live performances are distinguishable. Bell

concerned a dispute over common law trademark rights in the name of a musical group. Id. at 69-71. The First Circuit held that

while the original members of the group might have trademark rights in the mark in connection with live performances, they had no such rights in connection with the national recording

16

market, having acknowledged in their contracts with the recording studio that it was the sole owner of such rights. at 72, 75. Importantly, therefore, Bell concerned a dispute Id.

over trademark rights between group members and the music studio under whose management the group attained national prominence. See id. at 70. Moreover, the court expressly noted that it need

not resolve th[e] difficult matter of determining the rights of the group members if the studio sought to use the trademark to market recordings where the original group members had been replaced. Id. at 74. This case presents the very different

issue of whether a party, who is essentially a stranger to the creation of goodwill associated with a mark, may develop common law rights in the mark for live performances where the original owner maintains rights in the mark to market musical recordings. Finally, it is necessary to address briefly Marshaks claim that Horton abandoned any rights in the mark by agreeing in 1994 to the entry of a permanent injunction against her use of the mark. Hortons 1994 settlement agreement with Marshak does not Even if Horton abandoned

support Marshaks claim of ownership.

any rights in the mark she possessed by entering the agreement with Marshak, the mark did not enter the public domain. Assuming that the groups members, as opposed to Motown, retained rights in the mark after the group disbanded, it does

17

not follow that one group member could unilaterally abandon the group's rights in the mark at the expense members. Indeed, the other group

the case of singing groups or ensembles,

trademark rights are generally found to rest in the group as a collective, see, , Kingsmen, 557 F.Supp. at 182, and are not

found to follow an individual member who has left the group and seeks to use the rights to the exclusion of fellow group members. See Robi v. Reed, 173 F.3d 736, 740 (9th Cir. 1999)

In fact, Marshak himself adopts the point that trademark rights rest in the group rather than its individual members, and presses it quite vigorously in his opposition papers.

CONCLUSION The defendants' January 17 motion for summary judgment on Marshak's false designation of origin claim is granted. Marshak's January 17 motion for summary judgment on his false designation of origin claim is denied. SO ORDERED: Dated: New York, New York May 11, 2012

United

tes District Judge

18

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Shiga Japan RevisionDocumento2 pagineShiga Japan RevisionmschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Belair V MgaDocumento19 pagineBelair V MgamschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Decision Gosmile V Levine Re Wo PrjudiceDocumento7 pagineDecision Gosmile V Levine Re Wo PrjudicemschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Decision SDNY Personal Jursidcition VenueDocumento7 pagineDecision SDNY Personal Jursidcition VenuemschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Decision 2d Cir LV V LyDocumento60 pagineDecision 2d Cir LV V LymschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Complaint Cayman Jack V Jack DanielsDocumento11 pagineComplaint Cayman Jack V Jack DanielsmschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Complaint PreschooliansDocumento22 pagineComplaint PreschooliansmschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- LV To Penn Demand LetterDocumento4 pagineLV To Penn Demand LettermschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- ABC V Aereo ComplaintDocumento12 pagineABC V Aereo ComplaintmschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Decision Secalt Tirak Trade Dress ShapeDocumento19 pagineDecision Secalt Tirak Trade Dress ShapemschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Complaint MeltwaterDocumento135 pagineComplaint MeltwatermschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Complaint Boost OhioDocumento11 pagineComplaint Boost OhiomschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Penn Response To LVDocumento2 paginePenn Response To LVmschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Complaint Mega UMG FINALDocumento8 pagineComplaint Mega UMG FINALTorrentFreak_Nessuna valutazione finora

- Complaint SituationDocumento12 pagineComplaint SituationmschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Fighting The Unauthorized Trade of Digital Goods While Protecting Internet Security, Commerce and SpeechDocumento3 pagineFighting The Unauthorized Trade of Digital Goods While Protecting Internet Security, Commerce and SpeechStephen C. WebsterNessuna valutazione finora

- Complaint GloveablesDocumento11 pagineComplaint GloveablesmschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Complaint Cavern Club NevadaDocumento12 pagineComplaint Cavern Club NevadamschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Ttab Cavern Club 2 (A)Documento28 pagineTtab Cavern Club 2 (A)mschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Ttab Cavern Club 2 (A)Documento28 pagineTtab Cavern Club 2 (A)mschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Complaint in N Out BoomerangDocumento6 pagineComplaint in N Out BoomerangmschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Complaint Skull CandyDocumento16 pagineComplaint Skull CandymschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Brief False Advertising Calico CornersDocumento26 pagineBrief False Advertising Calico CornersmschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Samantha Schacher V Johnny ManzielDocumento3 pagineSamantha Schacher V Johnny ManzielDarren Adam Heitner100% (5)

- Complaint Varsity MSGDocumento21 pagineComplaint Varsity MSGmschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Complaint Rim BBXDocumento12 pagineComplaint Rim BBXmschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Complaint Ferracuti Law FirmDocumento13 pagineComplaint Ferracuti Law FirmmschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Decision Tree Freshner GettyDocumento23 pagineDecision Tree Freshner GettymschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Complaint Biggest LoserDocumento17 pagineComplaint Biggest LosermschwimmerNessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- 1.1 Cce To Proof of Cash Discussion ProblemsDocumento3 pagine1.1 Cce To Proof of Cash Discussion ProblemsGiyah UsiNessuna valutazione finora

- Ashish TPR AssignmentDocumento12 pagineAshish TPR Assignmentpriyesh20087913Nessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study For Southwestern University Food Service RevenueDocumento4 pagineCase Study For Southwestern University Food Service RevenuekngsniperNessuna valutazione finora

- The Cult of Shakespeare (Frank E. Halliday, 1960)Documento257 pagineThe Cult of Shakespeare (Frank E. Halliday, 1960)Wascawwy WabbitNessuna valutazione finora

- Special Power of Attorney: Know All Men by These PresentsDocumento1 paginaSpecial Power of Attorney: Know All Men by These PresentsTonie NietoNessuna valutazione finora

- Cir Vs PagcorDocumento3 pagineCir Vs PagcorNivra Lyn Empiales100% (2)

- Reading Comprehension: Skills Weighted Mean InterpretationDocumento10 pagineReading Comprehension: Skills Weighted Mean InterpretationAleezah Gertrude RegadoNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 1 Basic-Concepts-Of-EconomicsDocumento30 pagineChapter 1 Basic-Concepts-Of-EconomicsNAZMULNessuna valutazione finora

- Lec 15. National Income Accounting V3 REVISEDDocumento33 pagineLec 15. National Income Accounting V3 REVISEDAbhijeet SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Critique On The Lens of Kantian Ethics, Economic Justice and Economic Inequality With Regards To Corruption: How The Rich Get Richer and Poor Get PoorerDocumento15 pagineCritique On The Lens of Kantian Ethics, Economic Justice and Economic Inequality With Regards To Corruption: How The Rich Get Richer and Poor Get PoorerJewel Patricia MoaNessuna valutazione finora

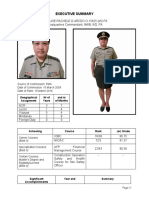

- Executive Summary: Source of Commission: PMA Date of Commission: 16 March 2009 Date of Rank: 16 March 2016Documento3 pagineExecutive Summary: Source of Commission: PMA Date of Commission: 16 March 2009 Date of Rank: 16 March 2016Yanna PerezNessuna valutazione finora

- EREMES KOOKOORITCHKIN v. SOLICITOR GENERALDocumento8 pagineEREMES KOOKOORITCHKIN v. SOLICITOR GENERALjake31Nessuna valutazione finora

- ACCT1501 MC Bank QuestionsDocumento33 pagineACCT1501 MC Bank QuestionsHad0% (2)

- Marketing Plan11Documento15 pagineMarketing Plan11Jae Lani Macaya Resultan91% (11)

- Anaphy Finals ReviewerDocumento193 pagineAnaphy Finals Reviewerxuxi dulNessuna valutazione finora

- Travel Reservation August 18 For FREDI ISWANTODocumento2 pagineTravel Reservation August 18 For FREDI ISWANTOKasmi MinukNessuna valutazione finora

- Statutory and Regulatory BodyDocumento4 pagineStatutory and Regulatory BodyIzzah Nadhirah ZulkarnainNessuna valutazione finora

- Buyer - Source To Contracts - English - 25 Apr - v4Documento361 pagineBuyer - Source To Contracts - English - 25 Apr - v4ardiannikko0Nessuna valutazione finora

- First Online Counselling CutoffDocumento2 pagineFirst Online Counselling CutoffJaskaranNessuna valutazione finora

- Hilti 2016 Company-Report ENDocumento72 pagineHilti 2016 Company-Report ENAde KurniawanNessuna valutazione finora

- Carl Rogers Written ReportsDocumento3 pagineCarl Rogers Written Reportskyla elpedangNessuna valutazione finora

- Ecology Block Wall CollapseDocumento14 pagineEcology Block Wall CollapseMahbub KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Case 1. Is Morality Relative? The Variability of Moral CodesDocumento2 pagineCase 1. Is Morality Relative? The Variability of Moral CodesalyssaNessuna valutazione finora

- JAR66Documento100 pagineJAR66Nae GabrielNessuna valutazione finora

- PERDEV2Documento7 paginePERDEV2Riza Mae GardoseNessuna valutazione finora

- SOL 051 Requirements For Pilot Transfer Arrangements - Rev.1 PDFDocumento23 pagineSOL 051 Requirements For Pilot Transfer Arrangements - Rev.1 PDFVembu RajNessuna valutazione finora

- Ez 14Documento2 pagineEz 14yes yesnoNessuna valutazione finora

- Acknowledgment, Dedication, Curriculum Vitae - Lanie B. BatoyDocumento3 pagineAcknowledgment, Dedication, Curriculum Vitae - Lanie B. BatoyLanie BatoyNessuna valutazione finora

- 78 Complaint Annulment of Documents PDFDocumento3 pagine78 Complaint Annulment of Documents PDFjd fang-asanNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender View in Transitional Justice IraqDocumento21 pagineGender View in Transitional Justice IraqMohamed SamiNessuna valutazione finora