Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Perfectionism in OCD

Caricato da

gerson_janczuraDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Perfectionism in OCD

Caricato da

gerson_janczuraCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Pergamon

Behav. Res. Ther. Vol. 35, No. 4, pp. 291-296, 1997 1997 ElsevierScience Ltd All rights reserved. Printed in Great Britain PII: S0005-7967(96)00108-8 0005-7967/97 $17.00 + 0.00

PERFECTIONISM IN OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE DISORDER PATIENTS

RANDY O. FROST ~* and GAIL S T E K E T E E 2

'Department of Psychology, Smith College, Northampton, MA 01063, U.S.A. and 2Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, U.S.A.

(Received 4 November 1996)

Summary--Considerable theory and anecdotal evidence has suggested that patients with ObsessiveCompulsive Disorder (OCD) are more perfectionistic. Evidence with non-clinical populations supports this hypothesis. However, no data are available on levels of perfectionism among patients diagnosed with OCD. The present study extends findings on perfectionism and OCD by comparing perfectionism levels of OCD-diagnosed patients with those of non-patients and a group of patients diagnosed with panic disorder with agoraphobia (PDA). As predicted, patients with OCD had significantly elevated scores on Total Perfectionism, Concern Over Mistakes, and Doubts About Actions compared to nonpatient controls. However, they did not differ from patients with PDA on Total Perfectionism or Concern Over Mistakes. Patients with OCD did have higher Doubts About Actions scores than those with PDA. The implications for the role of perfectionism in OCD and other anxiety disorders are discussed. (~ 1997 Elsevier Science Ltd

INTRODUCTION Perfectionism has played a prominent role in theorizing about Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), yet little attention has been paid to it in the research literature. As early as 1903, Janet (1903; as cited in Pitman, 1987a) assigned perfectionism a central role in the first two stages of his theory of OCD. Subsequently, psychoanalytic theorists have viewed perfectionism by OCD patients as attempts to maintain control by reducing the risk of harm and insuring safety (Mallinger, 1984; Salzman, 1968; Straus, 1948). Contemporary cognitive theorists have also suggested a primary role for perfectionism in understanding OCD. McFall and Wollersheim (1979) include perfectionistic beliefs as two of the four beliefs characteristic of primary appraisal deficits in a cognitive-behavioral model of OCD. Similarly, Guidano and Liotti (1983) theorized three central assumptions underlying OCD: perfectionism (including rumination over mistakes), need for certainty, and belief in perfect solutions. Also in a cognitive vein, Pitman's (1987b) cybernetic model of OCD contained elements of perfectionism, in that tolerance for error was hypothesized to be small. In addition to these theoretical accounts, there are clinical findings which suggest a link between perfectionism and OCD. Several studies have reported high levels of perfectionism among OCD patients, among their parents, or as noticeable childhood traits (Adams, 1973; Honjo et al., 1989; Lo, 1967; Rasmussen & Tsuang, 1986; Rasmussen & Eisen, 1989). However, these reports have not been systematic, nor have they used validated measures of perfectionism. More systematic research has been done on the link between perfectionism and OCD, but only among non-clinical or sub-clinical populations. Frost, Marten, Lahart and Rosenblate (1990) found significant correlations between Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMPS) subscales and scores on the Maudsley Obsessive Compulsive Inventory (Hodgson & Rachman, 1977) and the Everyday Checking Behavior Scale (Sher, Frost & Otto, 1983). In particular, the Concern Over Mistakes and Doubts About Actions dimensions of perfectionism were closely related to OCD symptoms. Frost, Steketee, Cohn and Greiss (1994) also found that among non-clinical Ss, perfectionism was associated with higher levels of OCD symptoms. Specifically, in multiple samples of Ss, sub-clinical OCD Ss scored higher on nearly all the

*Author for correspondence. 291

292

Randy O. Frost and Gail Steketee

dimensions of the FMPS. Other studies have reported similar findings. Rheaume, Freeston, Dugas, Letarte and Ladouceur (1995) found significant correlations between perfectionism (as measured by the FMPS) and obsessive-compulsive symptoms among non-clinical Ss. Once again, Concern Over Mistakes and Doubts About Actions were most closely related to OCD symptoms, while personal standards was only slightly correlated, and Parental Expectations and Parental Criticism were uncorrelated. Furthermore, perfectionism accounted for a significant portion of the variance in Padua Inventory scores after controlling for the influence of responsibility. Ferrari (1995) found the Perfectionistic Cognitions Inventory (PCI: Flett, Hewitt, Blankstein & Gray, 1994) to be significantly and positively correlated with scores on the Lynfield Obsessive-Compulsive Questionnaire and the Compulsive Activity Checklist among non-clinical Ss. Ferrari also found significant correlations between the PCI and the Lynfield ObsessiveCompulsive Questionnaire among a sample of people who reported having been diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive symptoms. This is the only finding in the literature that uses a clinical population. Unfortunately, however, the diagnostic status of these Ss is uncertain. Ferrari states that "it was not possible from the methods used to ascertain whether these volunteers were individuals diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive personality disorders or obsessive-compulsive personality" (p. 154). Given this uncertainty, it remains to be demonstrated that patients diagnosed with OCD will have higher levels of perfectionism than patients with other disorders or nonpatients. Several studies have reported correlations between perfectionism and specific obsessive-compulsive symptoms (i.e. checking, washing, hoarding). Gershunny and Sher (1995) found that non-clinical compulsive checkers had higher perfectionism scores on the FMPS than non-checkers. In addition, perfectionism partially mediated the relationship between OCD and task performance, as well as the subjective experience of performance among non-clinical Ss. Consistent with Salzman's theorizing, these authors hypothesized that perfectionism may lead checkers to attempt to exert more control over the events in their lives through checking rituals. Similarly, Tallis (1996) has hypothesized that there is a specific class of washing compulsions which results from perfectionism, that is, washing to achieve a 'perfect' state of cleanliness. Finally, across several different samples including students, community volunteers and self-identified compulsive hoarders, Frost and Gross (1993) found perfectionism (and most of its dimensions) to be correlated with compulsive hoarding. In addition to figuring prominently in OCD, perfectionism is one of the diagnostic criteria for Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD). Recent evidence has challenged the idea that OCD and OCPD are closely related (Baer et al., 1990), since diagnosis of OCPD occurs relatively rarely among those who meet criteria for OCD. Although OCPD may not be closely related to OCD, certain characteristics of OCPD may be so (Gibbs & Oltmanns, 1995; Pollack, 1987; Steketee~ 1990). Indeed, Frost and Gross (1993) found that measures of compulsive hoarding were not related to overall measures of OCPD~ but were correlated with certain OCPD symptoms, specifically perfectionism. Despite this plethora of evidence, no systematic study has yet shown higher levels of perfectionism among patients with OCD. The first purpose of the present study was to determine whether patients with OCD have higher levels of perfectionism than non-OCD individuals using a validated measure. Based on earlier findings we expected that OCD patients would have higher scores on Total Perfectionism, Concern Over Mistakes, and Doubts About Actions. Recent research on perfectionism has suggested that it is related to many types of psychopathology including depression (Blatt, Quinlan, Pilkonis & Shea, 1995; Hewitt & Flett, 1991), eating disorders (Bastiani, Rao, Weltzin & Kaye, 1995), and even other anxiety disorders such as social phobia (Juster et al., 1996; Mor, Day, Flett & Hewitt, 1995). Juster et al. (1996) compared social phobia patients with community volunteers and found social phobia patients higher in Concern Over Mistakes, Doubts About Actions and Parental Criticism. The findings from these studies raise some questions about the specificity of the association between perfectionism and psychopathology. Perfectionism may be a characteristic that cuts across a wide variety of disorders and is not specific to any one or two. Alternatively, certain dimensions of perfectionism may relate to certain disorders but not others. The second purpose of this investigation was

Perfectionismand OCD

293

to provide additional evidence regarding this question. While the dimensions of perfectionism, especially Concern Over Mistakes and Doubts About Actions, may be related to social phobia, depression, eating disorders, and OCD, there is some reason to think that OCD patients may have higher levels of perfectionism than patients with panic disorder and agoraphobia (PDA). Using the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire (PDQ), Mavissakalian, Hamann and Jones (1990) found that a larger percentage of patients with OCD were judged to be perfectionistic than patients with PDA. However, this finding must be viewed with some caution since the perfectionism items from the PDQ measure are unvalidated, and the alpha levels of the study may have been too liberal given the large number of comparisons made. This study attempted to determine whether patients with OCD have higher levels of perfectionism than patients with panic disorder/agoraphobia. This information will be useful in determining the role of perfectionism in theories of OCD.

METHOD

Subjects

Subjects for the experiment were 84 patients and community controls who ranged in age from 24 to 66 yr. The OCD group contained 35 patients diagnosed with OCD who were participating in a larger study of treatment outcome. There were 9 males and 26 females in the group with a mean age of 34.2 yr. The community control group contained 35 employees from an undergraduate college. Eleven males and 24 females had a mean age of 36.4 yr. The panic/agoraphobia group contained 14 Ss diagnosed with PDA who were participating in the same treatment study as the OCD group. The mean age for this group of 2 males and 12 females was 38.7 yr. All patients with OCD and PDA were diagnosed using the Structured Clinical Interview from DSM-III-R (Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon & First, 1990). None of these patients were comorbid for any other anxiety disorder diagnosis. There were no significant age differences among the groups, F(2,81) = 1.9, P > 0.05, and no significant differences in the gender composition of the groups, Z2 = 1.5, P > 0.05.

Measures

Subjects completed the revised Compulsive Activity Checklist (CAC-R: Steketee & Freund, 1991) which asks Ss to rate activities (e.g. retracing steps, locking doors, etc.) according to the extent to which they interfere with daily life on a scale from 0 (no problem) to 3 (unable to complete or attempt activity). This measure has shown good internal consistency and validity (Steketee & Freund, 1991). Subjects also completed the FMPS (Frost et al., 1990), a 35-item questionnaire that assesses overall perfectionism and 5 subscales. The Concern Over Mistakes subscale reflects negative reactions to mistakes, interpreting mistakes as equivalent to failure, and believing that one will lose respect following failure. Personal Standards reflects the setting of very high standards and the excessive importance placed on these high standards for self-evaluation. The perception that ones' parents set very high standards (Parental Expectations) and were overly critical (Parental Criticism) formed two other dimensions. The Doubts About Actions subscale reflects the extent to which people doubt their ability to accomplish tasks. Patients with OCD and PDA completed these measures prior to treatment.

RESULTS Table 1 presents means and standard deviations for the 3 groups. As expected, an analysis of variance on the CAC-R scores revealed a significant effect for group, F(2.81) = 18.5, P < 0.001. Multiple comparisons among the means of the three groups using a Scheff6 test (P < 0.05) indicated that the OCD patient group had significantly higher CAC-R scores than either the Panic Disorder/Agoraphobia group or the community controls (Table 1). The PDA group and the community controls did not differ from one another.

294

R a n d y O. F r o s t a n d G a i l S t e k e t e e T a b l e 1. M e a n s a n d s t a n d a r d d e v i a t i o n s f o r O C D , P D A a n d c o n t r o l s u b j e c t s OCD PDA 6.1 83,8 26.2 9.9 24.8 14.1 11.3 (11.8) b (23.3) ~ (10.0) ~ (4.6) b (5.7) (5.4) (5.4) b Control 4.0 66.5 18,5 8.1 22.4 11.5 6.9 (4.9) b (15.4) b (7.2) h (3,3) t' (5,5) (3.9) (2.9) ~ Social Phobia* --25.6 (7,5) 10.9 (3.7) 23.1 (5,8) 12,7 (6,0) 9.3 (3.9)

CAC-R Total Perfectionism Concern Over Mistakes Doubts About Actions Personal Standards Parental Expectations Parental Criticism

19.6 83.5 24.3 14.1 22.9 12.8 9.2

(14,9)" (22.8) ~' (9,8) i' (4.3) '~ (6,8) (4.5) (4.4) db

Note: In the first 3 columns, means with different superscripts are significantly different at the 0.05 level. *From Juster et al. (1996).

According to an analysis of variance of the FMPS, the groups showed significant differences on the predicted dimensions of perfectionism. There was a significant groups effect for Total Perfectionism, F(2,75) = 7.0, P < 0.01. Multiple comparisons (Scheff+) of the means of the three groups indicated that the OCD and PDA patient groups scored significantly higher than the community controls, but did not differ from one another (Table 1). Means and standard deviations for social phobia patients from the Juster et al. (1996) study are included in Table 1 for comparison. A similar result was found for the Concern Over Mistakes dimension where a significant group effect was evident, F(2,80) = 5.4, P < 0.01. Patients with OCD and PDA had higher scores (Ps < 0.05) than controls but did not differ from one another. The Doubts About Actions subscale showed a different pattern. There was a significant effect for group, F(2,80) = 20.9, P < 0.01, but patients with OCD had significantly higher scores than those with PDA, who did not differ from community controls. The OCD group scores were also significantly higher than the community controls. There was a significant group effect on Parental Criticism, F(2,78) = 6.4, P < 0.01. Multiple comparisons indicated that the PDA group scored higher than community controls, but the OCD group did not. No significant differences emerged on the Personal Standards, F(2,78) = 0.68, P > 0.05, or the Parental Expectations, F(2,78) = 1.8, P > 0.05, subscales.

DISCUSSION These findings are consistent with reports in the literature suggesting that there is a relationship between OCD and perfectionism. OCD patients scored higher in perfectionism than community controls on the Total Perfectionism score and on the 2 predicted dimensions of perfectionism, Concern Over Mistakes and Doubts About Actions. However, the findings also indicated that perfectionism was not specific to OCD, but occurred in panic/agoraphobia patients as well. The PDA patients differed from controls on the Total Perfectionism measure, Concern Over Mistakes, and Parental Criticism. Comparison of these data with those of Juster et al. (1996) suggest that high levels of Concern Over Mistakes, Doubts About Actions and Parental Criticism characterize social phobia patients as well. Thus, our findings do not confirm excessive perfectionism in OCD compared to other anxiety disorders. In light of the findings of this study, the Juster et al. (1996) study, and other recent studies (Bastiani et al., 1995; Hewitt & Flett, 1991; Mor et al., 1995), it is possible that perfectionism is a necessary condition for the development of many forms of psychopathology, but does not determine the exact nature of the disorder. Rheaume et al. (1995) suggest that perfectionism may be a "necessary but insufficient trait for development of O C D " (p. 793). Whether perfectionism is a necessary ingredient for the development of psychopathology remains to be shown, however. The fact that elevated levels of perfectionism are seen across a wide variety of disorders indicates that it is a construct worthy of more research. It is possible that certain features of perfectionism exist which distinguish OCD patients from other anxiety disorder patients. In the present samples, the Doubts About Actions dimension of perfectionism was the only one which distinguished OCD from PDA patients. Additionally, Doubts About Actions scores of OCD Ss in this study were higher than Doubts About Actions scores of social phobia Ss in the Juster et al. (1996) study. Doubting of the quality of one's

Perfectionism and OCD

295

actions has been a hallmark of OCD and indeed, may reflect symptoms of patients with checking rituals. It may also characterize other anxiety disorders as well (e.g. GAD). Rheaume et al. (1995) suggest that a different definition of perfectionism may be warranted with respect to OCD. Instead of Concern Over Mistakes, they suggest that a core belief that perfection is possible may characterize OCD patients. Others have proposed a similar hypothesis with respect to OCD symptoms (Frost & Hartl, 1996; Guidano & Liotti, 1983; McFall & Wollersheim, 1979). Further research is necessary to examine this possiblity.

REFERENCES

Adams, P. L. (1973). Obsessive children. New York: Brunner/Mazel. Baer, L., Jenike, M. A., Ricciardi, J, N., Holland, A. D., Seymour, R. J., Minichiello, W. E., & Buttolph, M. L. (1990). Standardized assessment of personality disorders in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Archives of General Psychiato,, 47. 826-830. Bastiani, A. M., Rao, R., Weltzin, T., & Kaye, W. H. (1995). Perfectionism in anorexia nervosa. International Journal O! Eating Disorders, 17, 147-152. Blatt, S. J., Quinlan, D. M., Pilkonis, P. A., & Shea, M. T. (1995). Impact of Perfectionism and need for approval on the brief treatment of depression, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psycholy. 63, 125-132. Ferrari, J. R. (1995). Perfectionism cognitions with nonclinical and clinical samples. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 10, 143-156. Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Blankstein, K. R., & Gray, L. (1994). The frequency of perfectionistic thinking and depressive symptomology. Manuscript under review. Frost, R. O., & Gross, R. C. (1993). The hoarding of possessions. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 31,367-381. Frost, R. O., & Hartl, T. L. (1996). A cognitive-behavioral model of compulsive hoarding. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 341-350. Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14, 449~,68. Frost, R. O., Steketee, G., Cohn, L., & Greiss, K. (1994), Personality traits in subclinical and non-obsessive compulsive volunteers and their parents. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 32, 47-56. Gcrshunny, B., & Sher, K. (1995). Compulsive checking and anxiety in a nonclinical sample: differences in cognition. behavior, personality, affect. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 17, 19-38. Gibbs, N. A., & Oltmanns, T. F. (1995). The relation between obsessive-compulsive personality traits and subtypes of compulsive behavior. Journal of A nxie O' Disorders, 9, 397-410. Guidano, V., & Liotti, G. (1983). Cognitive processes and emotional disorders. New York: Guilford. Hewitt, P. L,, & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism and depression: A multidimensional analysis. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 5, 423-438. Hodgson, R. J., & Rachman, S. (1977). Obsessional-compulsive complaints. Behaviour Researeh and Therapy, 15. 389 395. Honjo, S., Hirano, C., Murase, S., Kaneko, T., Sugiyama, T., Ohtaka, K., Aoyama, T., Takel, Y., lnoko, K., & Wakabayashi, S. (1989). Obsessive compulsive symptoms in childhood and adolescence. Acta Psychiatrica Scandanavica, 80, 83-91. Juster, H. R., Heimberg, R. G., Frost, R. O., Holt, C. S., Mattia, J. 1., & Faccenda, K. (1996). Social phobia and perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences. 21. 403-410. Lo, H. (1967). A follow-up study of obsessional neurotics in Hong Kong Chinese. British Journal of Psychiatry. 113, 823-832. Mallinger, A. E. (1984). The obsessive's myth of control. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis. 12. 147 165. Mavissakalian, M., Hamann, M. S., & Jones, B. (1990). A comparison of DSM-III personality disorders in panic/agoraphobia and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Comrehensive Psychiatry, 31,238-244, McFall, M. E., & Wollersheim, J. P. (1979). Obsessive-compulsive neurosis: A cognitive-behavioral formulation and approach to treatment. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 3, 333-348. Mor, S., Day, H. I., Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P, L. (1995). Perfectionism, control, and components of performance anxiety in professional artists. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 19, 207-225. Pitman, R. K. (1987a). Pierre Janet on obsessive-compulsive disorder (1903). Archives of General Psyehiatry, 44, 226232. Pitman, R. K. (1987b). A cybernetic model of obsessive-compulsive psychopathology. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 28, 334-343. Pollack, J. (1987). Relationship of obsessive-compulsive personality to obsessive-compulsive disorder: A review of the literature. The Journal of Psychology, 121, 137-148. Rasmussen, S. A., & Eisen, J. L. (1989). Clinical features and phenomenology of obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatric Annals, 19, 67-72. Rasmussen, S. A., & Tsuang, M. T. (1986). Clinical characteristics and family history in DSM-III obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 143, 317-322. Rheaume, J., Freeston, M. H., Dugas, M. J., Letarte, H., & Ladouceur, R. (1995). Perfectionism, responsibility, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 785-794. Salzman, L. (1968). The obsessive personality. New York: Jason Aronson. Sher, K. J., Frost, R. O., & Otto, R. (1983). Cognitive deficits in compulsive checkers: An exploratory study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 21,357-363.

296

Randy O. Frost and Gail Steketee

Spitzer, R., Williams, J., Gibbon, M., & First, M. (1990). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-lll-R--Patient Edition (Version 1.0). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. Steketee, G. (1990). Personality traits and diagnoses in OCD. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 4, 351-364. Steketee, G., & Freund, B. (1991). Compulsive activity checklist (CAC): Further psychometric analyses and revision. Behavioural Psychotherapy, 21, 13-25. Straus, E. W. (1948). On obsession: A clinical and methodological study. Nervous and Mental Disease Monograph, 73, 1948. Tallis, F. (1996). Compulsive washing in the absence of phobic and illness anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 361-362.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Advanced Casebook of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders: Conceptualizations and TreatmentDa EverandAdvanced Casebook of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders: Conceptualizations and TreatmentEric A. StorchNessuna valutazione finora

- Ghisi NJRE 2010 PDFDocumento37 pagineGhisi NJRE 2010 PDFHemant KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Agency and Free Will in OCDDocumento14 pagineAgency and Free Will in OCDElisaNessuna valutazione finora

- Greenberg2010 - Scrupulosity - A Unique Subtype of OCDDocumento8 pagineGreenberg2010 - Scrupulosity - A Unique Subtype of OCDRavennaNessuna valutazione finora

- OCDDocumento96 pagineOCDarunvangili100% (1)

- When A Family Member Has OCD Mindfulness and Cognitive Behavioral Skills To Help Families Affected by Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder by Hershfield, JonDocumento242 pagineWhen A Family Member Has OCD Mindfulness and Cognitive Behavioral Skills To Help Families Affected by Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder by Hershfield, JonJuliane MorenoNessuna valutazione finora

- OCD in Children and Adolescents: Causes, Symptoms, and TreatmentsDocumento10 pagineOCD in Children and Adolescents: Causes, Symptoms, and TreatmentsFaris Aziz PridiantoNessuna valutazione finora

- Cognitive Approaches to Obsessions and Compulsions: Theory, Assessment, and TreatmentDa EverandCognitive Approaches to Obsessions and Compulsions: Theory, Assessment, and TreatmentValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Ocd ChapterDocumento106 pagineOcd Chapteranon_292252833100% (1)

- Cognitive Therapy Critique for Anxiety DisordersDocumento10 pagineCognitive Therapy Critique for Anxiety DisordersaffcadvNessuna valutazione finora

- Impulse-Control DisordersDocumento6 pagineImpulse-Control DisordersRoci ArceNessuna valutazione finora

- OCD TreatmentDocumento1 paginaOCD TreatmentTarun KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- PMAD PresentationDocumento17 paginePMAD PresentationBrittany100% (1)

- The Relationship Between Eating Disorder Bevhavior and Myers-Briggs Personality TypeDocumento8 pagineThe Relationship Between Eating Disorder Bevhavior and Myers-Briggs Personality Typealexyort8Nessuna valutazione finora

- Thought Control and OcdDocumento10 pagineThought Control and OcdCella100% (1)

- Cognitive DisordersDocumento126 pagineCognitive DisordersDhen Marc100% (1)

- OCDDocumento49 pagineOCDAria AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- Cognitie-Behaioural Therapy For Body Dysorphic DisorderDocumento9 pagineCognitie-Behaioural Therapy For Body Dysorphic DisorderJon Lizarralde100% (1)

- Treatment Resistant OcdDocumento70 pagineTreatment Resistant Ocddrkadiyala2100% (1)

- Becoming AttachedDocumento1 paginaBecoming Attachedaastha jainNessuna valutazione finora

- Salkovskis Undesrstanding and Treating OCD 1999 PDFDocumento24 pagineSalkovskis Undesrstanding and Treating OCD 1999 PDFMannymorNessuna valutazione finora

- DBT Diary Card - BackDocumento2 pagineDBT Diary Card - BackCiupi Tik100% (1)

- The Psychology of Perfectionism An Intro PDFDocumento18 pagineThe Psychology of Perfectionism An Intro PDFRobi MaulanaNessuna valutazione finora

- ClassificationDocumento83 pagineClassificationDisha SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning To Live With OCD and Anxiety: Separating Myths from FactsDa EverandLearning To Live With OCD and Anxiety: Separating Myths from FactsNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Handbook of Understanding Panic and Anxiety DisorderDa EverandThe Little Handbook of Understanding Panic and Anxiety DisorderNessuna valutazione finora

- Pre-Therapy in PracticeDocumento29 paginePre-Therapy in PracticeAnonymous 2a1YI92k9LNessuna valutazione finora

- Religious Scrupulosity and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Historical ContextDocumento16 pagineReligious Scrupulosity and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Historical ContextMatej DragonerNessuna valutazione finora

- Child and Adolescent Interventions: Evidence-Based Treatments For AdhdDocumento22 pagineChild and Adolescent Interventions: Evidence-Based Treatments For Adhdnycsarah77Nessuna valutazione finora

- On Obscure Diseases of The Brain Disorders of The Mind 1000381106 PDFDocumento778 pagineOn Obscure Diseases of The Brain Disorders of The Mind 1000381106 PDFjurebieNessuna valutazione finora

- Ocd and Covid 19 A New FrontierDocumento11 pagineOcd and Covid 19 A New FrontierNaswa ArviedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bringing Clarity To Mental Rituals PDFDocumento4 pagineBringing Clarity To Mental Rituals PDFAnonymous uUrvuCt100% (1)

- OpMan Cram Sheet (Tenmatay)Documento7 pagineOpMan Cram Sheet (Tenmatay)Reg LagartejaNessuna valutazione finora

- Body Speaks From InsideDocumento7 pagineBody Speaks From InsideWangshosanNessuna valutazione finora

- Pathological Gambling: Prevalence, Diagnosis, Comorbidity, and Intervention in Germany Beate Erbas, Ursula G. BuchnerDocumento8 paginePathological Gambling: Prevalence, Diagnosis, Comorbidity, and Intervention in Germany Beate Erbas, Ursula G. Buchnerricardo00733Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Everything Health Guide to OCD: Professional advice on handling anxiety, understanding treatment options, and finding the support you needDa EverandThe Everything Health Guide to OCD: Professional advice on handling anxiety, understanding treatment options, and finding the support you needValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Assessing Executive Functioning with the CEFIDocumento3 pagineAssessing Executive Functioning with the CEFIKelly AdamchickNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary of Andrew J. Wakefield's Waging War On The Autistic ChildDa EverandSummary of Andrew J. Wakefield's Waging War On The Autistic ChildNessuna valutazione finora

- Primarily Obsessional OCDDocumento5 paginePrimarily Obsessional OCDRalphie_Ball100% (2)

- Bipolar MedicationDocumento5 pagineBipolar MedicationindarNessuna valutazione finora

- Hoarding DisorderDocumento2 pagineHoarding DisordermavslastimozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Impulse-Control Disorders Not Elsewhere Classified: Textbook of PsychiatryDocumento27 pagineImpulse-Control Disorders Not Elsewhere Classified: Textbook of Psychiatrykrysdana22100% (1)

- What Is OCDDocumento2 pagineWhat Is OCDMckayla SnyderNessuna valutazione finora

- Cognitive DistortionDocumento5 pagineCognitive DistortionOzzyel CrowleyNessuna valutazione finora

- Prescriptive Psychotherapies: Pergamon General Psychology SeriesDa EverandPrescriptive Psychotherapies: Pergamon General Psychology SeriesNessuna valutazione finora

- Body Dysmorphic DisorderDocumento5 pagineBody Dysmorphic DisorderAnonymous I78Rzn6rS100% (1)

- Coping with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Step-by-Step Guide Using the Latest CBT TechniquesDa EverandCoping with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Step-by-Step Guide Using the Latest CBT TechniquesNessuna valutazione finora

- Stoeber (2018) - The Psychology of PerfectionismDocumento25 pagineStoeber (2018) - The Psychology of PerfectionismIván FritzlerNessuna valutazione finora

- The Everything Parent's Guide to Children with OCD: Professional, reassuring advice for raising a happy, well-adjusted childDa EverandThe Everything Parent's Guide to Children with OCD: Professional, reassuring advice for raising a happy, well-adjusted childNessuna valutazione finora

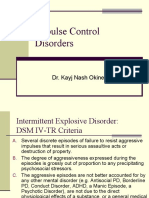

- Impulse Control Disorders: Dr. Kayj Nash OkineDocumento18 pagineImpulse Control Disorders: Dr. Kayj Nash OkineDivya ThomasNessuna valutazione finora

- Life in Rewind: The Story of a Young Courageous Man Who Persevered Over OCD and the Harvard Doctor Who Broke All the Rules to Help HimDa EverandLife in Rewind: The Story of a Young Courageous Man Who Persevered Over OCD and the Harvard Doctor Who Broke All the Rules to Help HimValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (14)

- Abramowitz Arch 2013 Improving CBT For OCD PDFDocumento12 pagineAbramowitz Arch 2013 Improving CBT For OCD PDFNitin KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Frederick Toates, Olga Coschug-Toates-Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Practical Tried-And-Tested Strategies To Overcome OCD-Class Publishing (2002)Documento280 pagineFrederick Toates, Olga Coschug-Toates-Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Practical Tried-And-Tested Strategies To Overcome OCD-Class Publishing (2002)utkins100% (5)

- Childhood DisordersDocumento26 pagineChildhood DisordersmojdaNessuna valutazione finora

- Leaving the OCD Circus: Your Big Ticket Out of Having to Control Every Little ThingDa EverandLeaving the OCD Circus: Your Big Ticket Out of Having to Control Every Little ThingValutazione: 2 su 5 stelle2/5 (1)

- Understanding Pure-O OCDDocumento23 pagineUnderstanding Pure-O OCDoverlytic100% (1)

- Clinical Psychology Case Study AllisonDocumento9 pagineClinical Psychology Case Study AllisonIoana VoinaNessuna valutazione finora

- OCD Relapse PreventionDocumento8 pagineOCD Relapse PreventionElena Estrada DíezNessuna valutazione finora

- OCD - Thinking Bad ThoughtsDocumento5 pagineOCD - Thinking Bad Thoughtshindu2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- PGCA Code of Ethics SummaryDocumento72 paginePGCA Code of Ethics SummaryJohn Carlo Perez0% (1)

- BACP: Working with bereaved clientsDocumento36 pagineBACP: Working with bereaved clientsMich RamNessuna valutazione finora

- Live Free: by Steven BancarzDocumento32 pagineLive Free: by Steven BancarzNikucNessuna valutazione finora

- NMIMS - PGDBM - Assignment - Organisational - Behaviour Sem1 - Dec2018Documento8 pagineNMIMS - PGDBM - Assignment - Organisational - Behaviour Sem1 - Dec2018rajnishatpecNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Draft EssayDocumento7 pagineFinal Draft EssayDweeYenNessuna valutazione finora

- J Dulek CapstoneDocumento231 pagineJ Dulek Capstoneapi-373373545Nessuna valutazione finora

- Bridget and Annelise Final LessonDocumento2 pagineBridget and Annelise Final Lessonapi-405381104Nessuna valutazione finora

- Alice Miller - Breaking Down The Wall of Silence - The Liberating Experience of Facing Painful Truth-Basic Books (2008) PDFDocumento186 pagineAlice Miller - Breaking Down The Wall of Silence - The Liberating Experience of Facing Painful Truth-Basic Books (2008) PDFBahar Bilgen Şen100% (2)

- Formal Observation Form IllingDocumento2 pagineFormal Observation Form Illingapi-285422446Nessuna valutazione finora

- MKT 233 - Mother MurphysDocumento12 pagineMKT 233 - Mother Murphysapi-302016339Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mentoring in Organizations GuideDocumento17 pagineMentoring in Organizations Guiderangelj13Nessuna valutazione finora

- Book Review On Communication TheoriesDocumento7 pagineBook Review On Communication TheoriesJessica Bacolta JimenezNessuna valutazione finora

- Bem-Transforming The Debate On Sexual InequalityDocumento7 pagineBem-Transforming The Debate On Sexual InequalityTristan_loverNessuna valutazione finora

- Jenson Shoes: Jane Kravitz's Story: Case AnalysisDocumento4 pagineJenson Shoes: Jane Kravitz's Story: Case AnalysisNakulesh VijayvargiyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mark M. Gatus, LPT Marck Zaldy O. Camba, LPT: Prepared By: Faculty Members, BU Philosophy DepartmentDocumento7 pagineMark M. Gatus, LPT Marck Zaldy O. Camba, LPT: Prepared By: Faculty Members, BU Philosophy DepartmentPrecious JoyNessuna valutazione finora

- 7 Making It Happen-Translating Vision Into RealityDocumento20 pagine7 Making It Happen-Translating Vision Into RealityAbdurrahman Maulana100% (1)

- Seven Secrets Signals EbookDocumento26 pagineSeven Secrets Signals EbookLucian Sala100% (1)

- Perfect MileDocumento6 paginePerfect Mileapi-284912923Nessuna valutazione finora

- Solved Mpob QBDocumento4 pagineSolved Mpob QBsimranarora2007Nessuna valutazione finora

- DELINQUENCY AND DRIFT - Travis PrattDocumento28 pagineDELINQUENCY AND DRIFT - Travis PrattGustavo RibeiroNessuna valutazione finora

- Cigna 2020 Loneliness FactsheetDocumento2 pagineCigna 2020 Loneliness FactsheetFernando NunesNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychic Powers (Time-Life Mysteries of The Unknown) PDFDocumento166 paginePsychic Powers (Time-Life Mysteries of The Unknown) PDFkumarnram100% (1)

- Mi + CBTDocumento9 pagineMi + CBTLev FyodorNessuna valutazione finora

- Health Locus of Control IDocumento2 pagineHealth Locus of Control IAnggita Cahyani RizkyNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 Guidelines To PLDP Asia Future Leaders 2020Documento10 pagine1 Guidelines To PLDP Asia Future Leaders 2020desa kanigoroNessuna valutazione finora

- Communication Process, Principles, and EthicsDocumento3 pagineCommunication Process, Principles, and EthicsElijah Dela CruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 2 Target SettingDocumento24 pagineChapter 2 Target SettingAthea SalvadorNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 - Director Promotion Process UAEDocumento2 pagine1 - Director Promotion Process UAEjay raneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Pediatrics 2005 LeBourgeois 257 65Documento11 paginePediatrics 2005 LeBourgeois 257 65merawatidyahsepitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Three Works Are Strictly Prohibited in My Class: 1.side Talk 2.drowsy 3.activate of Mobile RingtoneDocumento27 pagineThree Works Are Strictly Prohibited in My Class: 1.side Talk 2.drowsy 3.activate of Mobile RingtoneshazzadNessuna valutazione finora