Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

BMJ Publishing Group

Caricato da

babatoto210 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

18 visualizzazioni4 pagineJSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content. The principle of randomisation has been challenged for not being expedient1. The next two articles explain simple randomisation?that is, the equivalent to tossing a coin?and restricted randomisation procedures.

Descrizione originale:

Titolo originale

29502377

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoJSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content. The principle of randomisation has been challenged for not being expedient1. The next two articles explain simple randomisation?that is, the equivalent to tossing a coin?and restricted randomisation procedures.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

18 visualizzazioni4 pagineBMJ Publishing Group

Caricato da

babatoto21JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content. The principle of randomisation has been challenged for not being expedient1. The next two articles explain simple randomisation?that is, the equivalent to tossing a coin?and restricted randomisation procedures.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 4

BMJ Publishing Group

Assessing CIinicaI TviaIs WI Bandonise?

AulIov|s) SIeiIa M. Oove

Bevieved vovI|s)

Souvce BvilisI MedicaI JouvnaI |CIinicaI BeseavcI Edilion), VoI. 282, No. 6280 |Jun. 13, 1981),

pp. 1958-1960

FuIIisIed I BMJ Publishing Group

SlaIIe UBL http://www.jstor.org/stable/29502377 .

Accessed 23/03/2012 0759

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Digitization of the British Medical Journal and its forerunners (1840-1996) was completed by the U.S. National

Library of Medicine (NLM) in partnership with The Wellcome Trust and the Joint Information Systems

Committee (JISC) in the UK. This content is also freely available on PubMed Central.

BMJ Publishing Group is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to British Medical

Journal (Clinical Research Edition).

http://www.jstor.org

1958 BRITISH MEDICAL

JOURNAL

VOLUME 282 13

JUNE

1981

Statistics in

Question

sheila m gore

ASSESSING CLINICAL TRIALS

WHY RANDOMISE?

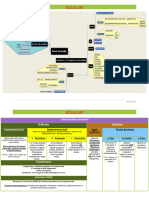

The

principle

of randomisation has been

challenged

for not

being expedient1:

randomised clinical trials

impose

a

discipline

on

patient

selection and accrual and make ethical considerations

explicit

and multicentre collaboration

necessary

if the duration

of

study

is to be limited. What has not been shown is that the

principle

is ill-founded.2

3

This article discusses reasons for

randomisation and reasons

against

other schemes of

assignment.

The next two articles

explain simple

randomisation?that

is,

the

equivalent

to

tossing

a coin?and restricted randomisation

procedures.

Randomised clinical trials remain the reliable

method for

making specific comparisons

between treatments.

(15)

What are the

purposes of

randomisation ?

?to

safeguard against

selection bias

?as

insurance,

in the

long

run,

against

accidental bias

?as the sinew of statistical tests

COMMENT

Firstly,

randomisation is the

only safeguard against

selection

bias: the doctor does not know the treatment

assignment

for the

next

patient,

and the

assignment

is

maximally unpredictable.

There can be neither

unwitting

nor deliberate selection because

there is no identifiable

pattern

in random allocation. When

better results are obtained in one treatment

group

than in others

this

may

be

explained (a) by

the

patient groups

not

being

comparable initially, (b) by

the

superiority

of a

particular

treatment,

or

(c) by

a

marginal

effect of treatment that was

enhanced because the distribution of

patients

to that treatment

group

was

slighdy

favoured. To eliminate a and c the

investigator

must at least be able to defend the method of

assigning

treat?

ment

against

the accusation of selection bias. The

following

example (see figure)

cannot be so defended?a

comparison

of

subsequent

seizure rates in three

groups

of children: 87 children

whose doctors decided to treat them with

long-term

anti

convulsant

drugs;

188 children who were not

given prophylactic

treatment;

and 229 children for whom

follow-up

was allowed to

lapse (none

of these was

given prophylactic treatment).

The

reason is that allocation of the children to these

groups

was

determined

by

the

paediatrician's

assessment and

by

the

stringency

of

follow-up.

Secondly,

randomisation is an insurance in the

long

run

against

substantial accidental bias between treatment

groups

with

respect

to some

important patient

variable. The

guarantee

applies only

to

large trials;

if fewer than 200

patients

are

randomised a chance imbalance between treatment

groups

will

need careful

analysis.

In the first Medical Research Council trial

of

radiotherapy

and

hyperbaric oxygen

for

patients

with head

and neck

cancer,4

294

patients

were randomised to

radiotherapy

in air or in

hyperbaric oxygen. Despite

the moderate trial size

the treatment

groups unfortunately

differed in the

proportion

of

patients

who had

lymph-node

m?tastases in the neck. The

hyperbaric oxygen group

had the

higher proportion

of

patients

?48%?compared

with

38%

of the 151

patients

who had been

randomised to treatment in air. A diverse

patient population pre?

sents a matrix of insufferable

complexity

.5

Although

randomisation

is the surest

way through

the

maze, investigators

should still

always

check that the

groups

as randomised do not differ with

respect

to characteristics that are assessed before treatment

begins.

Nineteen of 28

between-patient

trials

published

in the

Lancet from

July

to December 1977

reported making

a check

BRITISH MEDICAL

JOURNAL

VOLUME 282 13

JUNE

1981 1959

on how

comparable

the treatment

groups

were

initially;

there

was some imbalance in

respect

of

prognostic

factors in

eight

of

the 19 studies that made a check.

Investigators

should not be

misled into

believing

that because randomisation

guarantees

against

accidental bias in the

long

run that it does so in

every

instance.

Thirdly,

the

logical

foundation for

many

statistical tests is the

premise

that each

patient

could have received

any

one of the

treatments

being compared.

In the

survey

of 38 clinical trials from the Lancet referred to

in a

previous

article6 no trial was

uncontrolled,

but three trials

relied

solely

on historical controls. A

majority

of

prospective

trials were randomised

(22

out of

35),

but in

only

one trial was

the randomisation

procedure

described. Methods of randomisa?

tion can be learned

only

if authors refer to them.

Mosteller,

Gilbert,

and McPeek7

surveyed

controlled randomised trials in

myeloma

and

leukaemia, gastrointestinal cancer,

and breast

cancer.

Only

one-third of the 132 articles

reported

the method

of randomisation. Mosteller et ai

suggested

that authors should

briefly

describe how randomisation was

performed

because

only

then can the reader

properly

evaluate the trial.

They remarked,

"When the randomisation

leaks,

the trial's

guarantee

of lack of

bias runs down the drain."

(16)

Comment

critically

on the

following

non-random

assignment

schemes:

(i) by hospital

or

surgical

team;

(it) by assigning

treat?

ments

alternately; {Hi) by hospital number; (iv) by

date

of

birth.

(i)

liable to serious bias: not

only treatment,

but also

patients9

environment and medical

supervision

differ

(ii) by identifying

the treatment for the

previous

patient

doctors can deduce the next

assignment

(iii)

no

safeguard against

selection bias

(iv) assignment by

date of

birth,

because it is

systematic,

invites selection

bias;

correlation between

morbidity

and month of birth

COMMENT

(i) Competitive assignment?that is,

when

patients

referred

from different

hospitals

or

by

different clinicians receive

different treatments?is liable to serious bias. Not

only

the

treatments but also the

patients'

environment and medical

supervision differ,8

and the latter as much as the former could

account for

any

observed

response

difference. When the Medical

Research Council set

up

a multicentre trial to

compare

wound

infection rate after

major orthopaedic surgery

between

patients

operated

on in ultra-clean air and in other

theatres,

a condition

of the trial was that both

systems

were available in all the trial

centres and that the

surgical

teams

operated

in both ultra-clean

air and in other theatres in random

sequence

so

that, provided

the randomisation scheme was adhered to, neither centre nor

surgeon

would be a source of bias.

Comparison

of radical

operations

in rectal cancer

requires

that suitable

patients

are

assigned

at random to

type

of

operation

and that

surgical

skill is taken into account. A conservative

operation

is

technically

more difficult?if it were

performed

only by specialist

teams on

selectively

referred

patients

then

comparing

their results with the outcome of the radical

operation

by

other

surgeons

could not lead to an

unambiguous

recommen?

dation of either

procedure.

(ii)

Alternate

assignment

of treatments is

subject

to selection

bias if the doctor can

identify

the treatment for the last

patient

who entered the trial and so deduce the next

assignment.

The

knowledge may

make him defer

registration

of a

particular patient

until the treatment he

prefers

is due for

assignment

instead of

following

the unbiased

procedure?which

is never to

register

a

patient

for whom he has a definite treatment

preference.

Better

to limit the

population

of trial

patients

than to introduce bias.

Even if the trial treatments are

indistinguishable,

selection bias

can still

operate

if the doctor knows that the

assignment

scheme

is alternation. All he has to do is

guess correctly

the treatment

for one

patient

and he can then deduce the treatment for

every

subsequent patient.

(iii) Assignment by hospital

number is

unsatisfactory again

because there is no

safeguard against

selection bias. One of the

first

things

that the doctor notices when he looks at a

patient's

case notes is the

hospital number,

which is the

key

to treatment

assignment

for that

patient.

The

question:

"Has

forewarning

of

the treatment

group

influenced the doctors' decision about

whether or not to admit

patients

to the trial ?" will

always

be

asked,

and the doubt will

linger.

Stead9

reported

that the last

digit

of the

hospital

number was

used in 1953-5 to

assign patients

with tuberculosis to three

treatments in the ratio 30:30:40. The first and third treatments

included

streptomycin.

Six thousand and nine

patients

were

registered

in the trial. Their actual

distribution?32% (1898),

26% (1607), 42% (2504)?was significandy

different from the

target (p <0001);

the

regimen

that did not include

streptomycin

was avoided. Randomisation would have eliminated this

subjec?

tive element from the selection of treatment.

(iv)

Date of birth is almost as obvious a detail in the

patient's

1960 BRITISH MEDICAL

JOURNAL

VOLUME 282 13

JUNE

198

case notes as is

hospital number,

and

so, because it is

systematic,

assignment by

date of birth invites selection bias. There is a

second

objection?namely,

that there

may

be a correlation

between

morbidity

and month of birth.11 If

so,

then baseline

characteristics as well as treatment differ when

patients

are

allocated

by

date of birth. It is

unnecessary

to take this risk.

Random

assignment may

be

easily

achieved.

References

1

Gehan

E, Freireich E. Non-randomised controls in cancer clinical trial

JV

EnglJ

Med

1974;290:198-203.

2

Byar

DP.

Why

data bases should not

replace

randomized clinical trial:

Biometrics 1980

;36:337-42.

3

Meier P. Statistics and medical

experimentation.

Biometrics

1975;31

511-29.

4

Henk

JM,

Kunkler

PB,

Smith CW.

Radiotherapy

and

hyperbaric oxyge

in head and neck cancer. Lancet

1977;ii:101-3.

5

Black D. The

paradox

of medical care.

J

R Coll

Physicians

London 197?

13:57-65.

6

Gore SM.

Assessing

clinical

trials?design

I. Br

MedJ 1981;282:1780-1,

7

Mosteller

F,

Gilbert

JP,

McPeek B.

Reporting

standards and researc

strategies

for controlled trials.

Agenda

for the editor. Controlled Clinia

Trials

1980;1:37-58.

8

Irwin TT.

Surgeon-related

variables. Lancet

1978;ii:890.

9

Stead WW. A

suggested change

in the method of randomization c

patients

in

therapeutic

trials. Transactions

of

the 16th

conference

on th

chemotherapy of

tuberculosis. St Louis: Veterans

Administration,

1957.

10

Rosenberg HL,

Evans

M,

Pollock AV.

Prophylaxis

of

postoperative

le

vein thrombosis

by

low dose subcutaneous

heparin

or

preoperative

ca

muscle stimulation: a controlled clinical trial. Br

MedJ 1975;i:649-5)

11

Lewis

JA.

Randomization. Br

MedJ 1975;iii:41.

Sheila M

Gore, ma,

is a statistician in the MRC Biostatistics Unil

Medical Research Council

Centre,

Hills

Road, Cambridge

CB2

2QH

No

reprints

will be available

from

the author.

A

60-year-old

man has

suddenly developed

attacks

of blanching of

the

fingers lasting

30 minutes or so when

walking

in the cold. What

might

be

the cause and what advice should be

given

?

The late onset of

Raynaud's syndrome

in a man

certainly

deserves

some

simple investigation.

He should have a full blood count and

ESR,

and

possibly

antinuclear

factor,

to exclude an arteritis. Diabetes and

endocarditis also need to be excluded. It would be worth

taking x-rays

of his chest and neck to exclude cervical rib and

neoplasms

at the thora?

cic outlet. At the end of the

day, however,

artheroma of the

subclavian,

brachial,

or

digital

arteries is the most

likely

cause. A bruit

may

be

audible over the subclavian or brachial

artery.

If

symptoms

are

very

troublesome an arch

aortogram might

be

justified

to localise the

atheroma,

which

might occasionally

be amenable to

surgery. Simple

advice on

avoiding precipitating

factors

usually

suffices. In resistant

cases

reserpine

or

methyldopa

have been advocated.

What is the best method

of preventing

discoloration

of

the teeth in the

middle-aged

and

elderly

? Is

capping of

the

front

teeth

justifiable

in teeth

already

discoloured?

The

many

causes of discoloration of teeth in the

middle-aged

and

elderly may

be divided into "extrinsic" and "intrinsic." Extrinsic

discolorations are stains

deposited

on the surface of the

teeth,

often

from

nicotine,

tea or

coffee,

or combinations of

these,

and

may

be

removed without

difficulty by

the dentist or his

hygienist.

These

surface

stains, however,

also

penetrate

into the fine cracks that tend

to

develop

in enamel with

age,

and these are not

easily

removed.

When oral

hygiene

is

poor

dental

plaque

builds

up

and can become

discoloured and also calcified. When this calcification occurs beneath

the

gum margin

it

may

be darker in

colour,

and

appears

to

give

the

gum

and tooth a stained

appearance.

The common use of fluoridated

toothpastes

with a lower

polishing efficiency

than some non-fluoridated

toothpastes may

also contribute to the

build-up

of extrinsic stains. In

addition there is some evidence that some fluoridated

toothpastes may

contribute to the surface

staining.

With

aging,

the enamel

covering

may

become worn, resulting

in the

exposure

of the

underlying

dentine,

which is darker in colour and less transluscent than enamel.

Dentine often stains

heavily,

to a

greater depth

than

enamel,

and is

more difficult to clean.

Again,

the loss of attachment of the soft tissue

from the tooth as a

consequence

of

periodontal

disease

exposes

the

root surface

dentine,

which is a different colour and tends to stain.

Changes

that occur within the tooth cause "intrinsic"

staining.

Teeth do darken with

age,

but these

changes

are

slight

in the absenc

of

other, usually pathological,

factors. The commonest of these i

probably

dental

caries,

while the

darkening

of the tooth-tissue

adjacen

to a restoration

may

be due to caries

adjacent

to the restoration or th

passage

of metalic ions from an

amalgam

into the

adjacent

toot;

substance. Tooth-coloured restorations also

pick up

surface stain

after some time in the

mouth,

since

they

are made of resins with fille

particles,

and

may

become

unsightly.

When a

single

tooth become

less transluscent and darker than the

adjacent

teeth this is often du

to the death of the

pulp

or nerve of the tooth. This must be treat?

by removing

the dead

pulp

to

prevent

chronic or even acute infectio]

affecting

the bone

surrounding

the tooth and to deal with the aestheti

problem. Only

a dentist can advice in

any particular

case.

"Capping"

is

normally

referred to as

crowning

and should b

avoided if

possible

as the cause of discoloration can often be deal

with

by

other methods.

Though many

crowns are

made,

failures fror

one or more causes are not uncommon. It is not an

easy procedure

t

carry

out

successfully,

but when

performed competently

a crown

ma;

last a life time and be

indistinguishable

from a natural tooth. Bai

crowning

looks

unnatural,

causes

periodontal

disease

(disease

of th

gums),

kills the nerve of the

tooth,

interferes with the occlusion

(th

way

the teeth in each

jaw

relate to each

other),

and often falls off o

breaks. If a

single

tooth is discoloured and other methods are no

indicated to

improve

the

appearances, crowning may

not

present

to

many problems.

When several teeth are discoloured?for

instance,

th

six

upper

anterior teeth?then

crowning

should not be undertake!

lightly,

as this treatment

really

does need to be

carefully planned

an?

carried out

by

an

expert.

For

example,

if the discoloration results fron

attrition,

then the

problems

are

considerable,

for the whole occlusioi

is affected and

many posterior

teeth would need

crowning,

as well a

the six anterior teeth to stablise the

occlusion,

to

prevent

furthe

attrition to other

teeth,

and to allow a successful aesthetic result to b

achieved.

Crowns are

expensive

as time must be allowed for crowns that d<

not fit as well as

they should,

are

wrongly

contoured or

coloured,

o

have incorrect

markings. They

are

individually

made and need to b

constructed of

porcelain,

or

porcelain

fused to

metal, usually gold

Resin or

plastic

crowns should be considered

only

as

temporary,

o

at

very

best

"semi-permanent"

as the materials do not stand

up

t<

wear. The colour and

arrangement

of the anterior teeth can be o

great importance

to a

patient

and

may

be blamed

by many for variou

problems?the inability

to mix with

company,

a reluctance to smil

or

laugh

in

public,

or even the breakdown of

personal

relations

Consequen?y, although

contraindicated on all other

grounds crowninj

may

be

necessary

on

psychological

ones.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Dissertation Randomised Controlled TrialDocumento4 pagineDissertation Randomised Controlled TrialBuyAPaperOnlineUK100% (1)

- BLOCO 8 - Issues in Outcomes Research An Overview of Randomization Techniques For Clinical TrialsDocumento7 pagineBLOCO 8 - Issues in Outcomes Research An Overview of Randomization Techniques For Clinical TrialsIKA 79Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Limitations of Observation StudiesDocumento5 pagineThe Limitations of Observation StudiesalbgomezNessuna valutazione finora

- 未知Documento6 pagine未知Haiying MaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Analisis RCT Continuous Outcome - Google SearchDocumento13 pagineAnalisis RCT Continuous Outcome - Google SearchRaudhatulAisyFachrudinNessuna valutazione finora

- Precision Medicine Oncology: A PrimerDa EverandPrecision Medicine Oncology: A PrimerLorna Rodriguez-RodriguezNessuna valutazione finora

- Response ToDocumento7 pagineResponse ToReza AbdarNessuna valutazione finora

- 20.doctor-Patient Communication and Cancer Patients' ChoiceDocumento20 pagine20.doctor-Patient Communication and Cancer Patients' ChoiceNia AnggreniNessuna valutazione finora

- Best Practice & Research Clinical RheumatologyDocumento13 pagineBest Practice & Research Clinical RheumatologydrharivadanNessuna valutazione finora

- Experimental (Or Interventional) Studies: ConfoundingDocumento4 pagineExperimental (Or Interventional) Studies: ConfoundingRiza AlfianNessuna valutazione finora

- 12 Evidence Based Period Ontology Systematic ReviewsDocumento17 pagine12 Evidence Based Period Ontology Systematic ReviewsAparna PandeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Stat & ResearchDocumento276 pagineStat & ResearchSYED ALI HUSSAINNessuna valutazione finora

- tmp4F9 TMPDocumento7 paginetmp4F9 TMPFrontiersNessuna valutazione finora

- Triage Scale IpDocumento9 pagineTriage Scale IpYusriah Halifah SyarahNessuna valutazione finora

- Quasi-Experimentos Infect DeseaseDocumento8 pagineQuasi-Experimentos Infect DeseaseAlan MoraesNessuna valutazione finora

- Clin Trial Sep2004Documento2 pagineClin Trial Sep2004dvNessuna valutazione finora

- Setting A Research Agenda For Medical Over UseDocumento7 pagineSetting A Research Agenda For Medical Over UsemmNessuna valutazione finora

- Health Care Provider and Patient Preparedness ForDocumento10 pagineHealth Care Provider and Patient Preparedness ForTJ LapuzNessuna valutazione finora

- Donner Slides PDFDocumento61 pagineDonner Slides PDFRumana Sharmin ChandraNessuna valutazione finora

- Editorials: Evidence Based Medicine: What It Is and What It Isn'tDocumento4 pagineEditorials: Evidence Based Medicine: What It Is and What It Isn'tDanymilosOroNessuna valutazione finora

- FIRST StudyDocumento15 pagineFIRST Studykittykat4144321Nessuna valutazione finora

- 3.1A-Bolton 2007Documento10 pagine3.1A-Bolton 2007Michael SamaniegoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Science of Clinical Practice - Disease Diagnosis or Patient Prognosis - Croft Et Al 2015Documento8 pagineThe Science of Clinical Practice - Disease Diagnosis or Patient Prognosis - Croft Et Al 2015Bipul RajbhandariNessuna valutazione finora

- Project MoralesDocumento6 pagineProject MoralesDiane Krystel G. MoralesNessuna valutazione finora

- AmbulasiDocumento12 pagineAmbulasiRafii KhairuddinNessuna valutazione finora

- What Constitutes Good Trial Evidence?Documento6 pagineWhat Constitutes Good Trial Evidence?PatriciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Five Good Reasons To Be Disappointed With Randomized Trials - PMCDocumento5 pagineFive Good Reasons To Be Disappointed With Randomized Trials - PMCEDESSEU PASCALNessuna valutazione finora

- Users' Guides To The Medical Literature XIVDocumento5 pagineUsers' Guides To The Medical Literature XIVFernandoFelixHernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- Fogg and Gross 2000 - Threats To Validity in Randomized Clinical TrialsDocumento11 pagineFogg and Gross 2000 - Threats To Validity in Randomized Clinical TrialsChris LeeNessuna valutazione finora

- E BM DefinitionsDocumento2 pagineE BM DefinitionsIskandar HasanNessuna valutazione finora

- A Class Based Approach For Medical Classification of Chest PainDocumento5 pagineA Class Based Approach For Medical Classification of Chest Painsurendiran123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Evidence Based Medicine: What It Is and What It Isn'tDocumento3 pagineEvidence Based Medicine: What It Is and What It Isn'tCristian EstradaNessuna valutazione finora

- Radiation Oncology Incident Learning System (ROILS) Case StudyDocumento3 pagineRadiation Oncology Incident Learning System (ROILS) Case Studyapi-450246598Nessuna valutazione finora

- Review 20 - 03 - 20 - 001Documento18 pagineReview 20 - 03 - 20 - 001Ulices QuintanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Vascaccess 1996 Randolph CCMDocumento7 pagineVascaccess 1996 Randolph CCMFARHAN BADRUZ ZAMAN mhsD4TEM2020RNessuna valutazione finora

- Risk and Benefit For Umbrella Trials in Oncology: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocumento16 pagineRisk and Benefit For Umbrella Trials in Oncology: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDr Meenakshi ParwaniNessuna valutazione finora

- JurnalDocumento8 pagineJurnalAurima Hanun KusumaNessuna valutazione finora

- 3.3 Ayurveda: An Evidence-Based MedicineDocumento2 pagine3.3 Ayurveda: An Evidence-Based MedicinedffggNessuna valutazione finora

- Perioperative Laboratorytesting - The ClinicsDocumento6 paginePerioperative Laboratorytesting - The Clinicsapi-265532519Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ebn - MSDDocumento6 pagineEbn - MSDIrene NecesitoNessuna valutazione finora

- 13-Methods of RandomisationDocumento4 pagine13-Methods of Randomisationhalagur75Nessuna valutazione finora

- Apendicitis Antibst NEJ 20Documento2 pagineApendicitis Antibst NEJ 20Maria Gracia ChaconNessuna valutazione finora

- Get Homework/Assignment DoneDocumento6 pagineGet Homework/Assignment Donehomeworkping1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Trial RegistrationDocumento2 pagineClinical Trial Registrationmidi64Nessuna valutazione finora

- Making Informed Decisions: Assessing Strengths and Weaknesses of Study Designs and Analytic Methods For Comparative Effectiveness ResearchDocumento36 pagineMaking Informed Decisions: Assessing Strengths and Weaknesses of Study Designs and Analytic Methods For Comparative Effectiveness ResearchNational Pharmaceutical CouncilNessuna valutazione finora

- Reversals of Established Medical Practices: Evidence To Abandon ShipDocumento4 pagineReversals of Established Medical Practices: Evidence To Abandon ShipuoleoauNessuna valutazione finora

- 003 - 2014-06-13 - Evidence Based Medicine A Movement in CrisisDocumento7 pagine003 - 2014-06-13 - Evidence Based Medicine A Movement in CrisisAušra KabišienėNessuna valutazione finora

- Comments, Opinions, and Reviews: Recommendations For Advancing Development of Acute Stroke TherapiesDocumento9 pagineComments, Opinions, and Reviews: Recommendations For Advancing Development of Acute Stroke TherapiesDaniela Paredes QuirozNessuna valutazione finora

- 11.1 Diagnostic Tests 1-S2.0-S0001299818300941-MainDocumento7 pagine11.1 Diagnostic Tests 1-S2.0-S0001299818300941-MainHelioPassulequeNessuna valutazione finora

- Search BMJ GroupDocumento23 pagineSearch BMJ GroupCharles BrooksNessuna valutazione finora

- An Overview of Randomization Techniques - An Unbiased Assessment of Outcome in Clinical Research - PMCDocumento6 pagineAn Overview of Randomization Techniques - An Unbiased Assessment of Outcome in Clinical Research - PMCMUHAMMAD ARSLAN YASIN SUKHERANessuna valutazione finora

- Prognostic Predictive Markers Prognostic Predictive Prognostic PredictiveDocumento5 paginePrognostic Predictive Markers Prognostic Predictive Prognostic Predictivepre_singh2136Nessuna valutazione finora

- Eraker 1984Documento11 pagineEraker 1984Lorena PăduraruNessuna valutazione finora

- Using Pragmatic Clinical Trials To Test The Effectiveness of Patient-Centered Medical Home Models in Real-World Settings PCMH Research Methods SeriesDocumento11 pagineUsing Pragmatic Clinical Trials To Test The Effectiveness of Patient-Centered Medical Home Models in Real-World Settings PCMH Research Methods SeriesJames LindonNessuna valutazione finora

- Improving Medication Safety: Development and Impact of A Multivariate Model-Based Strategy To Target High-Risk PatientsDocumento13 pagineImproving Medication Safety: Development and Impact of A Multivariate Model-Based Strategy To Target High-Risk PatientstotoksaptantoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Magic of RandomizationDocumento5 pagineThe Magic of RandomizationRicardo SantanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Prostate Cancer: 10. Palliative Care: Clinical BasicsDocumento7 pagineProstate Cancer: 10. Palliative Care: Clinical Basicsdoriana-grayNessuna valutazione finora

- PCR 7 75Documento6 paginePCR 7 75Findri findriyantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Roils PaperDocumento4 pagineRoils Paperapi-633434674Nessuna valutazione finora

- Final Research Paper 2015Documento11 pagineFinal Research Paper 2015api-312565044Nessuna valutazione finora

- SG Annual Report To Ministers 2014Documento120 pagineSG Annual Report To Ministers 2014babatoto21Nessuna valutazione finora

- Wi-Fi Law: The Need To Capture and Retain User InformationDocumento3 pagineWi-Fi Law: The Need To Capture and Retain User Informationbabatoto21Nessuna valutazione finora

- Presentation Power of Data and Network VisualizationDocumento26 paginePresentation Power of Data and Network Visualizationbabatoto21Nessuna valutazione finora

- Wi-Fi Law: The Need To Capture and Retain User InformationDocumento3 pagineWi-Fi Law: The Need To Capture and Retain User Informationbabatoto21Nessuna valutazione finora

- Fenwick, LauraDocumento39 pagineFenwick, Laurababatoto21Nessuna valutazione finora

- Pub Policy Global Warming MemoDocumento9 paginePub Policy Global Warming Memobabatoto21Nessuna valutazione finora

- Catalog Aup 2011 0Documento127 pagineCatalog Aup 2011 0babatoto21Nessuna valutazione finora

- Small Is Beautiful - E F SchumacherDocumento210 pagineSmall Is Beautiful - E F Schumachercdwsg254100% (9)

- Bis Mark Ian AllianceDocumento9 pagineBis Mark Ian Alliancebabatoto21Nessuna valutazione finora

- AUP CatalogDocumento128 pagineAUP Catalogbabatoto21Nessuna valutazione finora

- American Universities Debating Tournament 2010Documento2 pagineAmerican Universities Debating Tournament 2010babatoto21Nessuna valutazione finora

- B5 (Animal Nutrition) - MSDocumento10 pagineB5 (Animal Nutrition) - MSMike Trần Gia KhangNessuna valutazione finora

- ICDASDocumento6 pagineICDAS12345himeNessuna valutazione finora

- Topical Fluoride in DentistryDocumento48 pagineTopical Fluoride in DentistryNur Shuhadah Shamsudin100% (1)

- Preventive MCQs CollectionDocumento44 paginePreventive MCQs CollectionOindrila Mukherjee100% (2)

- Ceramco 3 Guia de ColorDocumento2 pagineCeramco 3 Guia de Colorjuanpeter7_142595195Nessuna valutazione finora

- MCQs in DentistryDocumento135 pagineMCQs in Dentistrysam4sl98% (84)

- Art of Debonding in OrthodonticsDocumento2 pagineArt of Debonding in OrthodonticsmalifaragNessuna valutazione finora

- Baigusheva Et Al - Tooth of Early Generations - QI - 2016Documento14 pagineBaigusheva Et Al - Tooth of Early Generations - QI - 2016Bogdan HaiducNessuna valutazione finora

- 4 PDFDocumento6 pagine4 PDFYolan Novia UlfahNessuna valutazione finora

- Braz J Oral Sci-2023v22e230356Documento14 pagineBraz J Oral Sci-2023v22e230356Tutor TaweesinNessuna valutazione finora

- Dental Anomalies ملخصDocumento8 pagineDental Anomalies ملخصهند عبداللهNessuna valutazione finora

- AmeloglyphicsDocumento9 pagineAmeloglyphicsimi4100% (1)

- Understanding Dental Caries: 1 Etiology and Mechanisms Basic and Clinical AspectsDocumento14 pagineUnderstanding Dental Caries: 1 Etiology and Mechanisms Basic and Clinical AspectsnauvalNessuna valutazione finora

- Veneer Series PT 1Documento6 pagineVeneer Series PT 1Cornelia Gabriela OnuțNessuna valutazione finora

- Sle Exam QuestionsDocumento2 pagineSle Exam QuestionsdrgulafshanNessuna valutazione finora

- IPS IvocolorDocumento32 pagineIPS IvocolorToma IoanaNessuna valutazione finora

- DentinDocumento133 pagineDentinMohammed hisham khan100% (3)

- 23 - All-Ceramic Restorations PDFDocumento40 pagine23 - All-Ceramic Restorations PDFAlexandra StateNessuna valutazione finora

- Iccms - Caries 2015Documento13 pagineIccms - Caries 2015lauNessuna valutazione finora

- (David O. Klugh) Principles of Equine Dentistry PDFDocumento241 pagine(David O. Klugh) Principles of Equine Dentistry PDFJavier CeseñaNessuna valutazione finora

- TUTORIAL IN ENGLISH Blok 12Documento7 pagineTUTORIAL IN ENGLISH Blok 12Ifata RDNessuna valutazione finora

- CarteDocumento234 pagineCartereered100% (1)

- Australian Dental Journal - 2009 - Evans - The Caries Management System An Evidence Based Preventive Strategy For DentalDocumento9 pagineAustralian Dental Journal - 2009 - Evans - The Caries Management System An Evidence Based Preventive Strategy For DentalHarjotBrarNessuna valutazione finora

- Catalogue 2013-2014Documento20 pagineCatalogue 2013-2014Ahmed DolaNessuna valutazione finora

- CG A001 04 Radiographs GuidelineDocumento833 pagineCG A001 04 Radiographs GuidelinemahmoudNessuna valutazione finora

- RPT Science DLP Y3 (2020)Documento27 pagineRPT Science DLP Y3 (2020)Saidatun Atikah SaidNessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Techniques of Direct Composite Resin and Glass Ionomer RestorationsDocumento79 pagineClinical Techniques of Direct Composite Resin and Glass Ionomer RestorationsVidhi Thakur100% (1)

- Okawa Jurnal Denrad DelyanaDocumento6 pagineOkawa Jurnal Denrad DelyanaNoviana DewiNessuna valutazione finora

- Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Dental Restoration, Treatment and Consequences in A British NoblemanDocumento4 pagineEighteenth and Nineteenth Century Dental Restoration, Treatment and Consequences in A British NoblemanAmee PatelNessuna valutazione finora

- Pulp Therapy in Pediatric DentistryDocumento131 paginePulp Therapy in Pediatric DentistrydrkameshNessuna valutazione finora