Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Fed Courts Outline

Caricato da

randomqwerty2310Descrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Fed Courts Outline

Caricato da

randomqwerty2310Copyright:

Formati disponibili

Justiciability Doctrines 1. Prohibition Against Advisory Opinions - Federal courts cannot issue advisory opinions. (48) a.

In order for a case to be justiciable and not an advisory opinion, 2 conditions must be met. i. There must be an actual dispute between adverse litigants. (49) ii. There must be a substantial likelihood that a federal court decision in favor of the claimant will being about some change or have some effect. (51) 1. Ability of a non-judicial entity to ignore or modify judicial rulings will render a case non-jusitciable. (52) 2. Standing a determination of whether a specific person is the property party to bring a matter to the court for adjudication. a. Requirements for Standing (61) i. Injury (C) plaintiff must show that that he personally has sustained or is immediately in danger of sustaining some direct injury as the result of the challenged official conduct and the injury or threat of injury must be both real and immediate, not conjectural or hypothetical. (62) 1. Plaintiff seeking injunctive or declaratory relief must show a likelihood of future harm. (65) 2. What Injuries are sufficient? (69-71) a. Injuries to common law, constitutional, and statutory rights are sufficient for standing. b. Other sufficient injuries include: desire to use or observe an animal species, possible diminution of water allocations, economic harms, facing possible criminal prosecution, loss of the right to sue in the forum of ones choice, change in market conditions. (74) c. Insufficient injuries: stigmatic injury, marital happiness. ii. Causation (C) - Plaintiff must allege that the injury is fairly traceable to the defendants conduct. (75-76) iii. Redressability (C) - Plaintiff must allege that a favorable federal courts decision is likely to redress the injury. (75-76) iv. Limitation on 3rd party standing (P or C (Lujan, 99)) plaintiff may assert only his or her own rights and cannot riase the claims of third parties not before the court. 1. Exceptions the person seeking to advocate the rights of third parties must meet the constitutional standing requirements of injury, causation, and redressability in addition to one of the exceptions. a. Where the 3rd party is unlikely to sue (85) i. A person may assert the rights of a 3rd party not before the court if there are substantial obstacles to the 3rd party asserting his own rights and if there is reason to believe that the advocate will effectively represent the interests of the 3rd party. b. Where there is a close relationship between plaintiff and 3rd party

Page 1 of 16

i. Usually, 3rd party standing is permitted where the individual seeking standing is party of the 3rd partys constitutionally protective activity. c. Overbreadth doctrine i. Permits a person to challenge a statute on the ground that it violates the 1st amendment rights of 3rd parties not before the court, even though the law is constitutional as applied to defendant. (90) ii. In order for a statute to be declared unconstitutional on overbreadth grounds there must be substantial overbreadth (91). iii. Cannot be used in challenging regulations of commercial speech. (91) v. Prohibition against generalized grievances (P) a plaintiff may not sue as a citizen concerned with having the government follow the law or as taxpayers interested in restraining allegedly illegal government expenditures. 1. Exception is where plaintiff alleges a violation of a specific constitutional right even though everyone might suffer the injury as well. (92) 2. Exception for taxpayer standing to challenge government expenditures that violate the establishment clause (96). vi. Plaintiff be within the zone of interests protected by the statute (P) 1. Plaintiff must allege that the interest sought to be protected by the complainant is arguably within the zone of interests to be protected or regulated by the statute or constitutional guarantee in question. (100) 2. Used only in statutory cases, usually involving administrative law issues. (101) b. Special Standing Problems i. Standing for organizations 1. An organization has standing to sue on its own behalf if it has been injured as an entity (106). a. For example, can challenge conduct impeding its ability to attract members, raise revenues, or fulfill its purposes. 2. An association has standing to sue on behalf of its memebers when (107): a. Its members would otherwise have standing to sue in their own right; b. The interests it seeks to protect are germane to the orgnizations purpose; and c. Neither the claim asserted nor the relief requested requires the participation in the lawsuit for the individual members. THIS PRONG IS PRUDENTIAL and not necessarily required (see 108). ii. Legislators standing 1. Legislators have standing only if they allege either that they have been singled out for specially unfavorable treatment as opposed to other

Page 2 of 16

members of their bodies or that their votes have been denied or nullified. (110) 2. Remedial discretion (also called equitable discretion) can be a problem in these cases. It refers to the courts power to refuse to hear a case because it deemed it desirable to avoid review (111). iii. Standing for suits by government entities 1. Parens patriae standing (114) where a government sues to protect its citizens. a. Must allege both an injury to its citizens and that the matter involved is the type that the state is likely to address through its sovereign lawmaking process. b. 2 types of interests where a government has parens patriae standing (115). i. One is where the government is suing based on its interest in the health and well being both physical and economic of its residents in general. ii. Second, parens patriae standing exists to ensure that the state and its residents are not excluded from the benefits that are to flow from participation in the federal system. c. May not sue the federal government In this capacity, but may sue the federal government to protect their own sovereign or proprietary interests. (115) 3. Ripeness when a party may seek preenforcement review of a statute or regulation. (118) a. Criteria for determining ripeness i. How significant is the harm to denying judicial review (119). 1. 3 situations where the Supreme Court has found there to be sufficient hardship to justify preenforcement review. a. When an individual is faced with a choice between forgoing allegedly lawful behavior and risking likely prosecution with substantial consequences (120). b. Where the enforcement of a statute is certain and the only impediment to ripeness is simply a delay before the proceedings commence (123). c. Hardship from collateral injuries are present (124). 2. Case will be dismissed on ripness grounds if a federal court perceives the likelihood of harm as too speculative (126-127). ii. The fitness of the issues and record for judicial review (127). 4. Mootness An actual controversy must exist at all stages of federal court proceedings. (129). a. Vacatur (131). b. Exceptions to Mootness doctrine i. Where a collateral injury survives after the plaintiffs primary injury has been resolved. (132). 1. Criminal cases (132) case is not moot when the defendant has completed the sentence and continues to face adverse consequences of the criminal conviction. Page 3 of 16

2. Civil Cases (134) ii. Wrongs capable of repetition yet evading review 1. 2 Criteria must be met (136) a. Injury must be of a type likely to happen to the plaintiff again. b. It must be a type of injury of inherently limited duration so that it is likely to always become moot before federal court litigation is completed. iii. Voluntary Cessation (139). 1. A case is not to be dismissed as moot if the defendant voluntarily ceases the allegedly improver behavior but is free to return to it at any time. Only if there is no reasonable chance that the defendant could resume the offending behavior is a case deemed moot on the basis of voluntary cessation. This is a heavy burden that the defendant must prove in order to assert mootness. 2. Statutory change is enough to render a case moot, only if the court believes that there is not a likelihood of reenactment of a substantially similar law if the lawsuit is dismissed (143). 3. Compliance with a court order renders a case moot only if there is no possibility that the allegedly offending behavior will resume once the order expires or is lifted. (143) 4. Class actions a. A properly certified class action suit may continue even if the named plaintiffs claims are rendered moot. (members of the class continue to have a live controversy). b. Plaintiff may continue to appeal the denial of class certification even after her or her particular claim is mooted.

Page 4 of 16

Abstention judicially created rules whereby federal courts may not decide some matters before them even though all jurisdictional and justiciability requirements are met. Policy- (784) Pullman abstention (785) 1. Federal court abstention is required when state law is uncertain and a state courts clarification of state law might make a federal courts constitutional ruling unnecessary. The federal court should not resolve the federal constitutional question until the matter has been sent to state court for a determination of the uncertain issue of state law. a. Justifications for Pullman abstention (786) b. Criticisms of Pullman abstention (789) 2. Prerequisites for Pullman Abstention (790) a. There must be substantial uncertainty as to the meaning of the state law; AND b. There must be a reasonable possibility that the state courts clarification of state law might obviate the need for a federal constitutional ruling. 3. When abstention is appropriate and when it isnt. a. Abstention is required only if the states law is fairly subject to an interpretation which will render unnecessary a ruling on the federal constitutional issue. (791). b. Abstention is not necessary if a state law is patently unconstitutional, even if the state court has not yet construed it. (791) c. Abstention is appropriate when a statute is challenged as being unconstitutionally vague only if there is a substantial possibility that the state court could provide a narrowing construction that would save the statute from being invalidated. (792). d. Abstention is not appropriate, and state law is not to be deemed uncertain, merely because the state has not yet considered the laws constitutionality under the states constitution. (792) e. Abstention is required when the state has a constitutional provision unlike any that exists in the Untied States Constitution and the state courts construction of that clause might make the federal court ruling unnecessary. (793) f. Abstention is not proper if the federal and state constitutional provisions are identical, even if a state court decision on state constitutional grounds might render a federal court decision unnecessary. (793) 4. Procedures to be Followed (known as England Reservation) a. Parties may choose to litigate all of their issues, including federal constitutional claims, in state court but they relinquish the right to return to federal court. However, a party can expressly reserve the right to return to federal court for a determination of the federal law questions. Trying the state law issues in state court following federal court abstention will not preclude later litigation of the federal issues in federal court (traditional res judicata rule against splitting claims is inapplicable) (809). b. Problems with takings cases (810-811). c. If a state court refuses to decide the state law questions because of state constitutional provisions preventing advisory opinions, federal courts should dismiss the case without prejudice. (811) d. Certification may be an alternative to Pullman abstention (813)

Page 5 of 16

5. Unresolved issues a. Whether federal courts should weigh the costs of delaying a constitutional ruling (794) b. What interests are sufficiently important to justify refusing abstention or the weight to be given such interests (794). c. Economic consequences abstention has on the parties (795) d. Whether abstention is mandatory or discretionary (795) likely discretionary (796) e. Whether federal courts may abstain in a case where jurisdictional statutes create exclusive federal jurisdiction. (796) f. What constitutes adequate state procedures (796) g. Actual legal test for Pullman -2nd circuit vs. 5th circuit (796)

Thibodaux Abstention (799) 1. Federal courts should abstain in diversity cases if there is uncertain state law AND an important state interest that is intimately involved with the governments soverign prerogative. a. Soverign prerogative typically means issues involving dirt/water resources. 2. Certification may be an alternative for Thibodaux abstention. Burford Abstention (802) 1. Federal courts should abstain if there are unclear questions of state law AND there is a need to defer to complex state administrative procedures AND there is a danger that federal court review would disrupt the States attempt to ensure uniformity in the treatment of an essentially local problem.(administrative system must have a primary purpose of achieving uniformity within a state and judicial review would disrupt the proceedings and undermine the desired uniformity) (805) 2. Burford abstention results in the federal court completely dismissing the case (different from Pullman or Thibodaux abstention where the Court sends the case to state court for a clarification of state law issues but permits the case to return to federal court if necessary) (803) 3. Burford abstention is not appropriate in suits for monetary damages but only as to claims for injunctive or declaratory relief. (806) Younger Abstention (819) judicially created bar to federal court interference with ongoing state proceedings. 1. Bars federal courts from enjoining state criminal proceedings. 2. Bars federal courts from issuing a declaratory judgment invalidating a statute that is the basis of a pending state court criminal prosecution (833). 3. Younger abstention applies only to suits for injunctive or declaratory relief and not to claims for money damages (835). 4. Younger abstention results in the court completely dismissing the case. 5. In absence of pending state criminal proceedings. a. Federal courts may not provide declaratory judgments if a state prosecution is commenced before the federal court procedures are substantially completed (abstention is appropriate even if the federal complaint is filed before the state

Page 6 of 16

criminal proceedings begin if no proceedings of substance on the merits have taken place in federal court). (838) b. Federal courts may issue preliminary injunctions in the absence of state proceedings (842). The prevailing view among lower courts is that permanent injunctions are allowed in the absence of ongoing state proceedings. (843) Notes: Rooker-Feldman Doctrine bars federal district courts from reviewing state court decisions, except in criminal cases via a write of habeus corpus. Limited to situations where the state court judgment has been rendered before the federal proceedings have been commenced. (823) 6. When there are pending state civil proceedings a. Younger abstention applies in all civil proceedings to which the state is a party. (845) b. Younger abstention also applies in private civil proceedings (even between private parties) where an important state interest is present. (850) 7. When there are pending state administrative proceedings a. Younger abstention applies when there are state administrative proceedings in which important state interests are vindicated, so long as in the course of those proceedings the federal plaintiff would have a full and fair opportunity to litigate their constitutional claims. (852). i. Availability of state judicial review is an adequate opportunity to raise constitutional issues. 8. Exceptions to Younger abstention (858) a. Bad Faith Prosecutions i. Abstention is not appropriate in cases of bad faith prosecutions, defined as a prosecution has been brought without expectation of obtaining a valid conviction. (859). Also requires a showing of an absence of fair state judicial proceedings. (859) b. Patently Unconstitutional Law (860) i. Abstention is not appropriate for injunctions if there was a statute that was flagrantly and patently violative of express constitutional provisions in every clause, sentence, and paragraph. (860) c. Unavailability of an adequate state forum i. State proceedings will be considered inadequate if either impermissible bias is show or if there is no available state remedy. d. Waiver (863) Colorado River Abstention (865) 1. In general, federal courts should not stay or dismiss proceedings merely because the same matter is being litigated in state court. Only in rare, exceptional circumstances must a federal court relinquish jurisdiction because of simultaneous proceedings in state court. 2. When courts should abstain a. Real Property exception in actions concerning real property, whichever court has jurisdiction first is entitled to exclusive jurisdiction over the matter and even can enjoin other courts from hearing the case. Where a court has custody of property (in rem or

Page 7 of 16

quasi in rem) the state or federal court having custody of such property has exclusive jurisdiction to proceed. (869) b. Only when exceptional circumstances are present i. 5 Factors that federal court should consider when determining whether the interests of wise judicial administration and a comprehensive disposition of the litigiation outweigh the duty to exercise jurisdiction. (873) Factors are not a checklist and require a careful balancing of the considerations involved (877). 1. Problems that result when a state and federal court assume jurisdiction over the same res; 2. The relative inconvenience of the federal forum 3. The need to avoid piecemeal litigation 4. The order in which the state and federal proceedings were filed 5. Whether a federal question is present (877) a. The presence of a federal question weighs heavily against abstention. c. Suits for declaratory judgments i. Exceptional circumstances test doesnt apply for suits for declaratory judgments. (878) ii. Declaratory judgment Act allows federal courts to have discretion whether to abstain in suits for declaratory judgments when there are duplicative state proceedings. Appellate review of these decisions is by an abuse of discretion standard. (879)

Page 8 of 16

11th Amendment (11A) & Sovereign Immunity - Sovereign Immunity is based on the Supreme Courts interpretation of the 11A (422). 1. Suits that are barred. a. 11A precludes suits against a state government by citizens of another state or citizens of a foreign country. Also prohibits indian tribes from suing state governments in federal court without their consent (422). b. 11A bars suits against a state by its own citizens, also states cannot be named as defendants in federal administrative agency proceedings (424). c. State governments cannot be sued in state court without their consent (423). 2. Suits that are allowed a. Does not bar federal court suits by the US government against a state. b. Does not bar suits against a state by another state. But must be suing to protect its own interests and not on behalf of individual citizens. (424). c. Does not bar Appellate review by the Supreme Court of state court decisions where the state is a party (425). d. Does not bar admiralty suits (425). e. 11A and sovereign immunity do not apply in bankruptcy proceedings at all (425). f. Does not bar suits against municipalities or political subdivisions of a state. (426) i. But does bar suits against local governments when there is so much state involvement in the municipalities actions that the relief runs against the state (427). g. For state boards, corporations, and other entites when the law is uncertain, the court looks to several factors (429): i. Will a judgment against the entity be satisfied with funds in the state treasury? [Affirmative answer indicate the 11A will apply] ii. Does the state government exert significant control over the entitys decisions and actions? iii. Does the state executive branch or legislature appoint the entitys policymakers? iv. Does the state law characterize the entity as a state agency rather than as a subdivision? h. County official enforcing state law may be considered a state officer. (430). 3. Ways around the 11A a. Suits against state officers i. For injunctive relief 11A does not preclude suits against state officers for injunctive relief, even when the remedy will enjoin the implementation of an official state policy (432) or will cost the state a great deal of money in the future (438). But 11A bars retrospective damages to be paid from the state treasury. (439) ii. For monetary relief 1. 11A does not prevent suits against state officers for money damages to be paid out of the officers own pockets (individual capacity), even when the damages are retrospective compensation for past harms. (437) STATE INDEMNIFICATION POLICIES are irrelevant and would not prohibit relief. (437)

Page 9 of 16

2. 11A does prohibit a federal court from awarding retroactive relief (damages to compensate past injuries) when those damages will be paid by the state treasury (438). 3. Attorneys fees to be paid from state treasuries are to be considered ancillary to the relief already ordered by the court and are allowed (441). b. Exceptions i. 11A prohibits federal courts from hearing pendent state claims (state claims arising from the same nucleus of operative fact with federal claims) against state officers (444). ii. State officers cannot be sued to enforce federal statutes that contain comprehensive enforcement mechanisms (448). iii. State officers cannot be sued to quiet title to submerged lands (450). c. Waiver i. A state may waive its 11A immunity and consent to be sued in federal court. It may be sued in federal court, even for retroactive relief to be paid out of the state treasury. (452-453). ii. Express wavier To be effective, an express waiver must specify the states intention to subject itself to suit in federal court. A general waiver of sovereign immunity is not sufficient. iii. Constructive waivers are not allowed. (457) iv. States choice to remove to federal court was a waiver of sovereign immunity (458). d. Suits pursuant to federal laws i. Congress may authorize suits against state governments only when it is acting pursuant to 5 of 14A and only if the statute expressly authorizes suits against state governments. Congress may not override the 11A when acting under any other constitutional authority. (460). It must be a clear expression by Congress but the expression need not be in the statute itself, legislative history is sufficient. (463). ii. Congress is further limited to enacting laws that only prevent or remedy rights recognized by the courts and MAY NOT create new rights or expand the scope of rights. (467). Any new law must be narrowly tailored to solving constitutional violations; it must be proportionate and congruent to the constitutional violation. there must be a congruence and proportionality between the injury to be prevented or remedied and the means adopted to that end. (467-468) iii. Congress has greater latitude to legislate (and therefore more authority to permit suits against state governments) under 5 in cases involving a type of discrimination or where a fundamental right was implicated. (475).

Page 10 of 16

Section 1983 1. Creates a cause of action against any person who, acting under color of state law, abridges rights created by the Constitution and laws of the United States. 2. Federal court jurisdiction to hear 1983 suits exists under 28 USC 1331. 3. Rooker-Feldman Doctrine: Federal courts do not have jurisdiction pursuant to 1983 to review the judgments and decisions of state courts. 4. 1983 suits cannot be used by prisoners seeking to end or shorten their confinement. (502) But can be used by prisoners challenging their method of its implementation (503). 5. Under color of state law a. On duty - Actions taken by an officer in his or her official capacity constitute state action, whether or not the conduct is authorized by state law. (494). b. Off duty government officials factors used to determine whether the officer exercised state authority include: where there is a policy requiring officer to be on-duty at all times, whether the officer displayed a badge or an id card, identified himself as a police officer, or carried or used a service revolver or other weapon or device issued by the police department, and whether the officer purported to place the individual under arrest. (495). c. A professional (doctor, lawyer) employed by the government does not act under color of law ONLY if the individual employee is placed in a role inherently adverse to the government (such as a public defender). (496) d. Private individuals who conspire with government officials may be sued under 1983. (497). e. Federal officers may be sued under 1983 when they are engaged in a conspiracy with state officials to deprive constitutional rights. (498). 6. No Exhaustion requirement for 1983 a. State judicial remedies need not be exhausted (498) b. State administrative remedies need not be exhausted (498) c. Exception i. PLRA creates an exhaustion requirement before prisoners can bring lawsuits challenging prison conditions (500-501). Must exhaust even if no administrative remedies existed at the time the lawsuit was filed. (501). ii. In order to recover damages for an allegedly unconstitutional conviction or imprisonment, a plaintiff must first have the conviction or sentence reversed on appeal or expunged by executive pardon. (503) 7. Who is a person for purposes of 1983 a. Municipalities may be sued only for their own unconstitutional or illegal policies. (508) i. How is official policy proven? 1. Actions by municipal legislative body constitute official policies. (511) 2. Actions by municipal agencies or boards that exercise authority delegated by the municipal legislative body. 3. Actions by those with final authority for making a decision in the municipality constitute official policy for purposes of 1983. a. The determination of whether a person has final authority is a question of state law. b. 3 Elements identified by the 10th circuit (516): i. Whether the official is meaningfully constrained by policies not of that officials own making.

Page 11 of 16

ii. Whether the officials decisions are final (are they subject to review?) iii. Whether the policy decision purportedly made by the official is within the realm of the officials grant of authority 4. Demonstrating an official policy by establishing a government policy of inadequate training or supervision. (516) a. One instance is an insufficient basis for inferring the existence of a policy (517). b. Requires proof of a deliberate indifference by the local government. (517) i. Situations justifying a conclusion of deliberate indifference. 1. Failure to provide adequate training in light of foreseeable serious consequences that could result from the lack of instruction. 2. Failure to act in response to repeated complaints of constitutional violations by its officers. (518). 5. Demonstrate the existence of a custom. (521). a. Policy develops from the top-down, custom develops from the bottom-up. (521). b. Custom exists if policymakers knew about the widespread practice but failed to stop it. (521) c. 6th Circuit factors (521) ii. Pleading standard for municipal policy 1. Notice pleading standard (522) iii. Municipal liability 1. No qualified immunity for local governments (523) 2. Immune to claims for punitive damages. (524) b. Individual Officers i. Immunities (532NICE explanation of 11A and 1983) 1. Officers can invoke immunity ONLY if the plaintiff is suing them in their individual capacity (or the government is paying through an indemnification policy) (532). 2. Absolute Immunity a. In applying absolute immunity, the focus is on the function performed and not the title possessed. (for example, judges have absolute immunity for their judicial functions but not executive or administrative). (533). b. Judges have absolute immunity to suits for monetary damages or injunctive relief (535) for their judicial acts. (534). Expanded to cover individuals conducting certain adjudicative proceedings (537). c. Federal legislators and their aides have absolute immunity to suits for damages and prospective relief under the Speech and Debate Clause of Art. 1 Sec. 6. State and local legislators have absolute immunity both to suits for money damages and Page 12 of 16

equitable remedies. (538). Legislative immunity applies only to legislative acts (but not for public statements and press releases). d. Prosecutors are afforded absolute immunity for money damages. (539). This absolute immunity exists for prosecutorial tasks (in court behavior). Investigative acts by a prosecutor are protected only by qualified immunity (advice to police officers, wiretap, fabrication of evidence). (540). e. Police officers have absolute immunity for the testimony they give as witnesses, even if they commit perjury (543). They have only qualified, good faith immunity to suits against them pursuant to 1983. (543) f. President of the United States has absolute immunity for money damages for acts done while carrying out the presidency. No immunity for acts that occurred prior to taking office. (544) 3. Qualified Immunity a. Whether an officer is protected by qualified immunity, courts engage in a 2 step analysis. (548) i. A court should consider whether a constitutional right has been violated. And if so; ii. Court should determine whether it is a clearly established right (only federal law right) that a reasonable officer should know . (549) 1. Officers can be held liable so long as they had fair warning that their conduct was impermissible. (552-553) b. Private individuals sued under 1983 cannot claim qualified immunity. (557) c. State Governments and Territories i. State governments and territories are not persons under 1983 and thus may not be sued in state court under this statute. (559) 8. What federal laws may be enforced via 1983. a. 1983 can be used to create a cause of action whenever any federal law has been violated (562). i. Exceptions 1. 1983 cannot be used to enforce statutes that explicitly or implicitly preclude 1983 litigation. (563) a. Comprehensive enforcement mechanisms within a statute are evidence of congressional intent to preclude the remedy of suits under 1983. b. The presumption is in favor of 1983 to enforce a federal statute (564) except where the federal statute is more restrictive than 1983 (565). In that case, the presumption is against 1983. c. The existence of administrative remedies alone does not preclude 1983 litigation absent a more specific congressional intent.

Page 13 of 16

2. 1983 is available only to enforce federal statutes that create rights (565). a. Several factors which indicate that a federal statute is an enforceable right include (567): i. The statute creates a binding obligation ii. If the interest created by the statute is sufficiently specific as to be judicially enforceable iii. If the provision was intended to benefit the plaintiff. iv. Provision must be written in mandatory rather than precatory terms. (568) 9. 1983 for Constitutional Claims (570)

Page 14 of 16

Federal Common Law 1. Refers to the development of legally binding federal law by the federal courts in the absence of directly controlling constitutional or statutory provisions. (363) 2. 2 categories where federal common law has developed (368) a. To protect federal interests. i. 2 part inquiry whether to create federal law to safeguard federal interests. 1. Whether the matter justifies creating federal law. a. Proprietary interest of the US (in contract, property, and torts) has been held to justify the creadtion of federal law. (376). i. Exception: Custom-made, hand-tailored specifically negotiated transaction (377). 2. What should its content be? a. Copy existing state law principles or formulate new rules? ii. In suits between private parties 1. Federal common law will be developed in suits between private parties only if federal law is deemed to preempt state law (383). Preemption will be found if a state law imposes obligations that are mutually exclusive with federal law, or if a state law frustrates the achievement of a federal objective, or if there is a clear congressional intent to preempt state law. (383) iii. In international relations 1. Foreign policy interests justify federal common law (383). iv. To resolve disputes between states 1. Interstate harmony justifies creation of federal common law. (385) b. To effectuate congressional intent (occurs in 2 situations) (388). i. Congress wants federal courts to develop a body of common law under a particular statute.(390) ii. The creation of private rights of action under federal statutes. 1. Will create such causes of action under federal statutes where it is necessary to effectuate Congresss intent. (393) a. There must be affirmative evidence of Congresses intent to create a private right of action (397).

Page 15 of 16

Habeas Corpus (Table of Contents pg 889) 1. Rules Governing Habeas Corpus a. Writ of HC may be granted by the SC, any justice thereof, the district courts, and any circuit judge within their respective jurisdictons (903). b. Successive petitions are only allowed with the approval of a US Court of Appeals and the denial of such permission is not reviewable by the supreme court. (904) c. HC petitions must be in writing, signed, and verified by the person for whom relief is requested or someone acting on their behalf. Must describe the facts concerning the applicant commitment or detention and the basis for the writ. Should name the custodian as the respondent.(904) d. Federal court may grant HC if it concludes that the person is held in custody in violation of the Constitution, laws, or treaties of the US. (904). e. Individuals in state government custody may bring a HC petition only if they have exhausted all available state remedies. f. Fed courts need not entertain a petition for a writ of HC if a previous petition presented the same issues and the petition does not present any new ground. (905) i. Successive HC petitions could not be brought unless the inmate could show cause for not presenting the issue in the first petition and prejudice to not having the successive petition heard. (905) ii. A court of appeals may approve a successive petition only by finding either: 1. That the claim relies on a retroactive new rule of constitutional law; or 2. That the factual predicate for the claim could not have been discovered earlier and that the facts are sufficient to establish by clear and convincing evidence that no reasonable fact finder would have found the applicant guilty of the underlying offense. (905) g. Courts have authority to grant HC to individuals held in custody with their respective jurisdictions. (905) i. Individuals held in custody by a state containing more than 1 federal judicial district may file a petition in either the district where the individual is held in custody or in the district that encompasses the state court that convicted the individual. Both of these district courts have jurisdiction to hear the HC petition and can transfer the matter to the other if the interests of justice would be served. ii. If a petition is filed in the wrong federal judicial district, the court without jurisdiction may transfer the petition to the appropriate court. h. There is a 1 year statute of limitations on HC petitions and only 6 months in capital cases where a state has established an adequate system of providing attorneys in postconviction proceedings. (only AZ has met the standard) (909) i. The final order of a judge in a HC proceeding is subject to review on appeal by the court of appeals. May appeal only if the federal district court judge or a court of appeals judge issues a certificate of appealability. (910) i. Standards for certificate of appealability are on 910. 2. Prereqs of HC a. Relaxed standard of being in custody (911-914)

Page 16 of 16

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Natural Resource Law Outline Class NotesDocumento37 pagineNatural Resource Law Outline Class Noteslogan doop100% (1)

- Commerce Clause FlowchartDocumento1 paginaCommerce Clause FlowchartMark Adamson100% (1)

- Diversity Jurisdiction Flow ChartDocumento1 paginaDiversity Jurisdiction Flow ChartimalargeogreNessuna valutazione finora

- Answering A Con Law QuestionDocumento1 paginaAnswering A Con Law QuestionBrat WurstNessuna valutazione finora

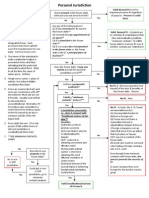

- Personal Jurisdiction FlowchartsDocumento2 paginePersonal Jurisdiction FlowchartsAlodieEfamba100% (5)

- Con Law II Notes & CasesDocumento71 pagineCon Law II Notes & CasesKunal Patel100% (1)

- Sales and Leases Outline FinalDocumento64 pagineSales and Leases Outline FinalC.W. DavisNessuna valutazione finora

- EP Flow ChartDocumento6 pagineEP Flow Chartmikunta100% (1)

- Outline For First AmendmentDocumento101 pagineOutline For First Amendmentcalisublime84100% (2)

- State ActionsDocumento1 paginaState ActionsKatie Lee WrightNessuna valutazione finora

- First Amendment OutlineDocumento27 pagineFirst Amendment Outlineancanton100% (3)

- Licenses and Easements, CovenantsDocumento32 pagineLicenses and Easements, CovenantsterencehkyungNessuna valutazione finora

- Supplemental Jurisdiction Flow ChartDocumento1 paginaSupplemental Jurisdiction Flow ChartStephanie Lemchuk0% (2)

- Con Law Speech OutlineDocumento2 pagineCon Law Speech OutlineEl0% (1)

- EvidenceDocumento48 pagineEvidenceKYLE HOGEBOOMNessuna valutazione finora

- Con Law Cheat Sheet (Judicial Tests)Documento4 pagineCon Law Cheat Sheet (Judicial Tests)Rachel CraneNessuna valutazione finora

- Federal Courts Nutshell OutlineDocumento2 pagineFederal Courts Nutshell OutlineHeather Kinsaul Foster50% (2)

- Fed Courts Full OutlineDocumento63 pagineFed Courts Full OutlineKalana KariyawasamNessuna valutazione finora

- Con Law II OutlineDocumento59 pagineCon Law II OutlineHenry ManNessuna valutazione finora

- Con Law 1 Attack OutlineDocumento6 pagineCon Law 1 Attack Outlinemkelly2109Nessuna valutazione finora

- Con Law II Due Process Flow 1253147333Documento9 pagineCon Law II Due Process Flow 1253147333Jesse Hlubek100% (1)

- Law School Survival Guide (Volume II of II) - Outlines and Case Summaries for Evidence, Constitutional Law, Criminal Law, Constitutional Criminal Procedure: Law School Survival GuidesDa EverandLaw School Survival Guide (Volume II of II) - Outlines and Case Summaries for Evidence, Constitutional Law, Criminal Law, Constitutional Criminal Procedure: Law School Survival GuidesNessuna valutazione finora

- Fed Courts Short OutlineDocumento20 pagineFed Courts Short Outlineelithesp100% (1)

- Federal Courts OutlineDocumento92 pagineFederal Courts Outlinefavoloso1100% (2)

- Con Law 2 Gulasekaram 1Documento10 pagineCon Law 2 Gulasekaram 1Big BearNessuna valutazione finora

- Con Law OutlineDocumento22 pagineCon Law OutlineslavichorseNessuna valutazione finora

- Federal Courts OutlineDocumento21 pagineFederal Courts OutlineHeather Kinsaul FosterNessuna valutazione finora

- Constitutional Law I Funk 2005docDocumento24 pagineConstitutional Law I Funk 2005docLaura SkaarNessuna valutazione finora

- Dormant Commerce ClauseDocumento2 pagineDormant Commerce ClauseEva CrawfordNessuna valutazione finora

- Con Law II OutlineDocumento49 pagineCon Law II OutlineAdam Warren100% (1)

- Professor Arthur Miller Friedenthal, Miller, Sexton, Hershkoff, Civil Procedure: Cases and Materials, 9 EdDocumento14 pagineProfessor Arthur Miller Friedenthal, Miller, Sexton, Hershkoff, Civil Procedure: Cases and Materials, 9 Edaasquared1100% (1)

- Con Law SkeletalDocumento20 pagineCon Law Skeletalnatashan1985Nessuna valutazione finora

- Con Law Outline!Documento42 pagineCon Law Outline!Liam Murphy100% (1)

- Con Law PracticeDocumento10 pagineCon Law PracticeNick ArensteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Con Law Outline For 1 and 2 Good OutlineDocumento35 pagineCon Law Outline For 1 and 2 Good Outlinetyler505Nessuna valutazione finora

- Con Question OutlineDocumento5 pagineCon Question OutlineKeiara PatherNessuna valutazione finora

- Labor Law OutlineDocumento32 pagineLabor Law OutlineIsabella LNessuna valutazione finora

- Professional Responsibility OutlineDocumento38 pagineProfessional Responsibility Outlineprentice brown50% (2)

- Evidence Flash CardsDocumento12 pagineEvidence Flash CardskoreanmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Con Law II OutlineDocumento27 pagineCon Law II OutlineNija Anise BastfieldNessuna valutazione finora

- Clear and Present Danger Test: Advocacy of Illegal ActionDocumento98 pagineClear and Present Danger Test: Advocacy of Illegal ActionDavid YergeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Crim Law OutlineDocumento52 pagineCrim Law OutlineJohn MichaelNessuna valutazione finora

- Con Law Study GuideDocumento4 pagineCon Law Study GuideekfloydNessuna valutazione finora

- Conlaw Shortol ChillDocumento2 pagineConlaw Shortol ChillBaber RahimNessuna valutazione finora

- PJ Flow Chart (Revised)Documento1 paginaPJ Flow Chart (Revised)Chris CeNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Organizations OutlineDocumento29 pagineBusiness Organizations OutlineMissy Meyer100% (1)

- Introduction The Role of Federal Courts: Main OutlineDocumento46 pagineIntroduction The Role of Federal Courts: Main OutlineNicole SafkerNessuna valutazione finora

- Evidence Mini ReviewDocumento10 pagineEvidence Mini ReviewAna Lucia MarquezNessuna valutazione finora

- Speedy, and Inexpensive Determination of Every Action and ProceedingDocumento43 pagineSpeedy, and Inexpensive Determination of Every Action and ProceedingDan SandsNessuna valutazione finora

- Judicial Review: Marbury v. MadisonDocumento35 pagineJudicial Review: Marbury v. MadisonXi ZhaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Con Law II OutlineDocumento29 pagineCon Law II OutlineLangdon SouthworthNessuna valutazione finora

- Criminal Law Outline SAKSDocumento29 pagineCriminal Law Outline SAKSJames LeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Con Law Outline E&EDocumento18 pagineCon Law Outline E&ETony Aguilar100% (1)

- Mass Media Outline Spring 2007Documento33 pagineMass Media Outline Spring 2007Melissa GonzalezNessuna valutazione finora

- M R O I. C: Carey v. PiphusDocumento67 pagineM R O I. C: Carey v. PiphusAyers100% (1)

- Constitutional Law FunkDocumento20 pagineConstitutional Law FunkLaura Skaar100% (2)

- Constitutional Law II Outline: Instructor: BeeryDocumento22 pagineConstitutional Law II Outline: Instructor: BeeryBrian Brijbag100% (1)

- A Legal Lynching...: From Which the Legacies of Three Black Houston Lawyers BlossomedDa EverandA Legal Lynching...: From Which the Legacies of Three Black Houston Lawyers BlossomedNessuna valutazione finora

- Reaching the Bar: Stories of Women at All Stages of Their Law CareerDa EverandReaching the Bar: Stories of Women at All Stages of Their Law CareerNessuna valutazione finora