Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

I Have A Preference For Working With Well Written Old Books Plus Databases Rather Than New Books

Caricato da

amurali1965Descrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

I Have A Preference For Working With Well Written Old Books Plus Databases Rather Than New Books

Caricato da

amurali1965Copyright:

Formati disponibili

I have a preference for working with well written old books plus databases rather than new books,

mainly because the new books are out of date anyway and they also don't explain things.

Bent Larsen once said something to the effect that it's one thing to be a good writer but quite another to explain how you intend to beat Portisch the next time. In any case a book about a particular opening is only useful as a starting point, mapping out the territory which you then need to explore for yourself. Some explanation of the strategy is a good thing, but after that it's necessary to think and make your own decisions and choices.

If you like the way someone plays a particular opening, check out what they play in other openings too. It could be that you've found a good model whose thinking accords with your own.

There never was a Soviet school of chess and the success of Soviet players had nothing to do with its coaching methods. It was not the 'Botvinnink school', Dvoretsky, Dorfman or any other chess guru. This is all a big con, perpetrated by people who wanted to secure their place within the 'system' by being pillars of its so-called 'school'. And lest we forget, Bobby Fischer exposed it.

As for the principles of how to improve your game, they can be stated very simply: a) Immerse yourself in chess culture b) Analyze your own games, avoiding self deception c) Play in the best tournaments you can get And that's it.

I'm a firm believer in studying games collections of very strong players: In my youth I worked through the games of Lasker, Capablanca, Rubinstein, Alekhine, Botvinnik, Larsen and Fischer. This is also a superb way to educate yourself in chess.

There are plenty of books of openings propaganda (all crushing wins for one side or the other) if that's what you want. Of course if you think that these books 'prove' that an opening is good by giving a large percentage of the results you want to see, I suggest that you try it in practice. It should be educational....

One very important aspect of actually achieving something is, I believe, the ability to avoid making excuses, in all their guises. I have heard almost every excuse under the sun why people have lost a game, protecting the ego but inhibiting the learning process. Similarly people will claim that either they or their peers would have achieved such and such if only they'd done such and such or not had such and such a thing holding them back. Blah, blah, blah...

I've always found it difficult to study openings ... some might say that it shows! Amongst the things that I have done are playing through lots of games collections, solving positions against the clock and playing a lot. I've learned most from analysing with strong players (usually after games that I lost). I suspect that my greatest strength is that I tend to look at things for myself using a board and pieces. What is even more interesting is that my fellow professionals are similarly 'unstructured'. I don't know where all the well taught students are, they certain don't seem to have titles.

Amongst GMs I'm not alone in thinking that the openings you play early on are the ones that you feel most comfortable with. I see this in itself as an argument against focusing too much on gambits/tactical play, I think that kids need to move on to real openings as quickly as possible (they tend to interpret these in tactical fashion anyway, depending on where they are in the learning curve.)

It is interesting that a player's 'intuition' normally improves with age (experience) whilst their tactical ability will tend to deteriorate. To me this suggests that there is very little direct connection between these two types of thought; it also suggests that chess is a whole-brained game in which getting experience as early as possible gives you the best chance of having good intuition whilst your left brain is still sharp enough to calculate quickly.

I think we mislearn a lot about chess and acquire bad thinking habits. Central to this is not checking things carefully and instead going by 'feel'. There is, for example, a huge overestimation of the strength of 'attacking positions' at club level. Unless players start checking positions for themselves at some point (ie processing the information which comes their way) they'll continue to misassess these things based on generalities such as 'this looks dangerous'. This is why we must ANALYSE, ANALYSE, ANALYSE. And NOT generalise!

The vast majority of players will have some degree of laziness in their thoughts both during and in between games; they talk about chess a lot, skim through lots of books but don't actually sit down, get a board and pieces out and analyze chess positions.

If you write about openings you don't play you can tell the whole truth... On the other hand it's boring and maybe even a little stupid to write about the openings you do play.

And no, I feel no guilt about having no 'anger to win', I'm very cold blooded about these things. These days I gauge tournament success very much in terms of the overall financial returns; for me this is the only perspective a professional player should have. Of course one can reach the conclusion that it's better to try and win most games for this particular purpose.

I know very few professional players with very fixed views; in some games they take pawn centres and in others demolish the same centres. The tendency is to become 'universal' and not have particular prejudices about things.

Things always look different when you're at the board. I've lost count of the number of times I've cooked up some idea at home only to see the drawbacks when I think about playing it in a real game. The problem with a live opponent is that he has a vested interest in destroying our ideas. We, on the other hand, have a vested interest in seeing them work so we can admire our own handiwork and congratulate ourselves on being such clever chaps. Of course this creates a tendency to overlook contradictory details....

'Understanding' comes on many different levels. The people who manage to 'digest' are the ones who will sit for hours in front of a chess set, tinkering with ideas, or those who play THOUSANDS of games with particular ideas. Not those who just read and nod...

I think that one of the great problems with trying to learn chess like academia is that usually there is no 'right answer' as such. You can spot players who think there is - they can be a fountain of knowledge but are never quite to the pitch of the ball when it comes to thinking about a real position. So they read every book under the sun and talk a magnificent game ... but remain weak.

What is the difference between chess and other subjects? It's the ever-present reality of the opponent the guy that tries to defeat our every idea. So the nicely illustrated examples crumble into dust when you read them in a book and then try and use them in practice... unless you've tested them with a zillion 'what-ifs'.

After many years I reached the conclusion that everything you do at the board should be automatic trying to remember things is a mind killer. This is where the 'digestion' of chess ideas comes in - it's the process whereby conscious 'knowledge' becomes instinctive. And I'm convinced that it's better to have a small supply of well digested knowledge than a huge supply of things you've read but don't have 'hardwired' into you at an instinctive/subconscious level.

Some basic guidelines for analyzing one of your own games:

a) Make a note of what you were thinking during the game immediately when it finishes and check your thoughts against those of your opponent in the post-mortem. b) Check your conclusions with Fritz and use ChessBase or similar to check the theory. Are you missing alternative ideas and plans? c) If you have access to a stronger player, see what he thinks about your conclusions/analysis. Are you missing alternative ideas and plans? d) Find the errors made in a to c. e) Find the errors made in d. f) Find the errors made in e. g) Find the erros made in f.

Are you getting the picture?

Dedication is the key factor that means you really go to town on the material. And there's no great mystery about this, it's the way people achieve excellence in any sphere. But people always want an easy short cut.

My boyhood idols were Lasker and Botvinnik - and I never got to play Kasparov.... Of course I'd like the chance, but these days there are no tournaments of 'mixed' strength.

Just as a boy becomes a man when he walks around his first puddle, chessplayers reach maturity when they are willing to play normal positions that arise from normal openings rather than the oddball stuff designed to trick your opponent early on or force the pace from the outset. And in this regard I have a confession to make; I was still jumping into the puddles age at the age of 30 with my slimy tricks in the Modern etc, but I became a GM when I started to play more 'normally'.

Two players I have the greatest admiration for are Victor Korchnoi and Bent Larsen. Both of them are tremendous fighters both on good days and on bad, and this is despite playing at the very top and having their livelihood depend on their results.

It's easy to be brave against weak opposition when you have nothing at stake. Much harder when you're a full time pro and it's the likes of Petrosian, Karpov or Botvinnik sitting opposite you...

It's amazing how bad much published analysis is; you discover this when you check it, especially with Fritz running in the background. And once a mistake has been made it is usually copied uncritically by other authors...

So don't be surprised when players rehabilitate variations which were thought to be bad. All that has happened is that someone checked the reason a variation was thrown away and discovered that the death certificate was signed prematurely.

As Victor Korchnoi points out in his book of best games, when you study openings you don't remember the variations. What happens is that the strategic motifs become familiar to you at a deeper level which means getting the kind of positions in which you know what to do.

I see the division between tactics and strategy as being artificial; they should be interweaved at every moment of the thinking process.

One thing that I find very useful about even the worst books is that they provide can a starting point for thinking about something, even if completely wrong and full of mistakes...But I don't like to criticize books even if they are written rather quickly, instead taking the view that their usefulness depends on the reader rather than the author...

Most GMs will study complete and well-annotated games when trying to learn a new opening - in Dvoretsky's 'Opening Preparation' you can find a discussion of this with Razuvaev being quoted as suggesting 6 model games for each opening. I find lists of variations completely unfathomable myself, so the study requirement for GMs may not be as different as you believe...

So I'm sorry to say confusion is healthy and that there are no straightforward answers. The good news is that you don't need them, all that's required for chess is to play slightly better moves than your opponent...

I think that the amount of theory someone needs to know depends very much on what level they have to play at. Over the years it's been very noticeable to me that very few of my students' games have followed theoretical paths for very long (correspondence chess not included!). Probably this is because non-professionals don't have time to study, so everyone's looking for decent side-lines which don't make great demands on their time.

For most players it's better to have a knowledge of plans and ideas, be able to get playable positions out of the opening and put the main focus on general playing skills. And there's no need whatsoever to memorize sharp variations.

I must be fortunate in that I've never had an 'average' student and many of mine have made great strides. And if you believe that Grandmasters have no insights to offer 'average' players such as yourself, perhaps you have stumbled across the reason that you're not getting any better.

I consider myself very fortunate to have read the works of such great players as Lasker, Korchnoi, Capablanca and others and never fail to learn something. Even if I'm distinctly 'average' by comparison...

I personally am planning to be improving and winning tournaments into my 90s, despite a growing reluctance to leave home.... Only you can decide if you want a similar goal and then set about achieving it.

If someone is learning a language should they start off by intensely studying novels in that language or with simpler and clearer material? There's a reason why Capablanca, Karpov and others have recommended studying chess from the endgame..

If you are saying that the 'chess act' (Gerald Abrahams' description of the decision making process on a single move) is by far the most important thing then I think you are right. And there are many factors in this process; understanding, experience, vision, mental discipline and prejudice ('knowing' things that are not actually true).

Many things can help improve a player's decision making process, but one of the big problems is when someone doesn't know what's wrong with it. The most common explanation people have for their lack of success in chess is deficient opening knowledge; usually it's something else, but this something varies from person to person.

Imho it's really better not to try to memorize anything - the only stuff that will stick are things that can be hung on hooks of deep understanding. If you have good abilities in calculation and vision, much can be worked out during the game; what is 'theory' anyway other than a collection of imperfect games which have, for the most part, been analyzed rather badly.

You're best forearmed by understanding the middlegame structures that come from your openings.

A good way to conduct these trials is to imprison 160 chess players in solitary confinement arranging them in 4 groups of equal strength. Then you give 3 of the groups one of the chess books whilst the control group has something by Delia Smith. Then you compare their results when they're let out, discovering to your horror that Delia Smith was the winner.

During my teenage years I followed Kotov's advice in 'Think Like a Grandmaster' to practice analyzing positions, writing down what I saw in a certain amount of time and then comparing it with the notes to the position concerned. I believe it was very helpful and certainly my grade improved year after year.

I think that it's useful to compare the process of learning chess with that of learning a musical instrument (I was fortunate in having this model around because of familly members). It takes time and effort and there are no shortcuts or magic ingredients.

It's always been popular to scapegoat the players for 'Grandmaster draws', but the problem is that the players are often acting rationally in making them. I don't think it's that difficult to come up with tournament systems whereby draws would not make much sense (e.g. mini-matches at a faster time limit in which only a win or loss were possible) - so instead let's blame the governing bodies for their lack of imagination.

The problem with tournaments is that you only have a say in where you move your own pieces - not in those of your opponents or the rest of the players. I think it's important to understand that our control over the outcome is limited in this way, and that worrying about such matters is nothing but a distraction.

The best and only thing we can do is to try to keep playing good moves.

I'm not a big fan of the Blumenfeld rule (write down your move, look for simple threats and only then play it) and I've found that using it all the time takes my attention away from the game. But recently I've found that writing down my moves before playing them can be very useful in winning positions.

I believe that the reason for this is that in certain highly charged situations ones emotions can interfere with clear thinking. In such cases more methodical thinking, inefficient and stilted though it is, can produce stable results.

Draw offers are not covered much by the books but can be of great practical importance. The first thing to note is the information they are supposed to convey ("I am happy with a draw"), but I don't believe this

is necessarily the case. I've found them of value when my opponent has the better position but is not handling his clock too well. In this case a draw offer is a way of asking if he wants to roll the dice, And thinking about this question (i.e. using more clock time) can tip the odds further against him should he decline.

There are a number of top professionals (e.g. Morozevich & Korchnoi) who have expressed the view that White's supposed advantage in chess does not actually exist. This thought is very liberating, as we are not then obliged to follow the 'best' moves (& 30 moves of theory) in order to achieve nothing. Instead we can achieve nothing by other means, whilst playing fresh and interesting positions.

Chess is to a considerable extent about pattern recognition. The more patterns you have firmly fixed in your memory, the more effective you are likely to be at the chessboard. John Nunn

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Autosport Magazine 2014 01 16 EnglishDocumento120 pagineAutosport Magazine 2014 01 16 EnglishAnna GajdácsiNessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Chess LessonsDocumento17 pagineChess Lessonsaristir0% (1)

- Inside Chess - Vol.3, No.3 (19-Feb-1990) PDFDocumento27 pagineInside Chess - Vol.3, No.3 (19-Feb-1990) PDFRicardo MartinezNessuna valutazione finora

- Inside Chess - Vol.6, No.7 (19-April-1993)Documento22 pagineInside Chess - Vol.6, No.7 (19-April-1993)non plus ultraNessuna valutazione finora

- Botvinnik - Volume 3 PDFDocumento490 pagineBotvinnik - Volume 3 PDFravidahiwala100% (11)

- Brimnes Ikea ManualDocumento40 pagineBrimnes Ikea ManualbleeeewNessuna valutazione finora

- The NemesisDocumento13 pagineThe NemesisSATISH m25% (4)

- 2009 - Chess Life 05Documento84 pagine2009 - Chess Life 05KurokreNessuna valutazione finora

- Karpovs Strategic Wins 1 - 1961-1985Documento460 pagineKarpovs Strategic Wins 1 - 1961-1985hiltondesenhista100% (12)

- B22 Sicilian Alapin by GM SveshnikovDocumento42 pagineB22 Sicilian Alapin by GM SveshnikovCristian100% (4)

- 2012 Dec Chronicle AICFDocumento52 pagine2012 Dec Chronicle AICFamurali1965Nessuna valutazione finora

- 46 C Eng. Com XDocumento24 pagine46 C Eng. Com XVibhuti RoyNessuna valutazione finora

- 46 - F - Science - XDocumento14 pagine46 - F - Science - XMandeep Singh PlahaNessuna valutazione finora

- Discovery of GodDocumento24 pagineDiscovery of Godssagar_usNessuna valutazione finora

- Family Floater Health Guard v4Documento2 pagineFamily Floater Health Guard v4amurali1965Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hyundai Santro XingDocumento2 pagineHyundai Santro Xingamurali1965Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Amazing Qur'An: Dr. Gary MillerDocumento19 pagineThe Amazing Qur'An: Dr. Gary Milleramurali1965Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mahradū An Indian Story With Some ObserDocumento73 pagineMahradū An Indian Story With Some Obseramurali1965Nessuna valutazione finora

- Nakkheeran 05-06-2013 (WWW - Freedomusertech.blogspot - Com)Documento50 pagineNakkheeran 05-06-2013 (WWW - Freedomusertech.blogspot - Com)amurali1965Nessuna valutazione finora

- 175Documento5 pagine175pummypandeyNessuna valutazione finora

- E BrochureDocumento2 pagineE Brochureamurali1965Nessuna valutazione finora

- CloningDocumento16 pagineCloningamurali1965Nessuna valutazione finora

- Shell V-Power Race Fuel V Shell V-Power Road FuelDocumento2 pagineShell V-Power Race Fuel V Shell V-Power Road FuelMilan DjokicNessuna valutazione finora

- Las Series Del Vissla ISA World Junior Surfing ChampionshipDocumento7 pagineLas Series Del Vissla ISA World Junior Surfing ChampionshipDUKENessuna valutazione finora

- 400 Kings Gambit MinisDocumento138 pagine400 Kings Gambit MinisKartik ShroffNessuna valutazione finora

- GP2 Insider Issue 57Documento4 pagineGP2 Insider Issue 57dvdg9999Nessuna valutazione finora

- KeresDocumento27 pagineKeresmaginonNessuna valutazione finora

- Viswanathan AnandDocumento8 pagineViswanathan Anandhackiftekhar100% (1)

- TS20170706 T1956139604 No Limit Hold'em $10+$1Documento59 pagineTS20170706 T1956139604 No Limit Hold'em $10+$1Matheus Girardi ScalabrinNessuna valutazione finora

- Bajrang PuniaDocumento2 pagineBajrang PuniaAnurag SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Ronaldinho BiographyDocumento4 pagineRonaldinho BiographyGathitha Thraviesa100% (1)

- Calendar CRO 3 13 2021Documento3 pagineCalendar CRO 3 13 2021HBvLNessuna valutazione finora

- Challenging The GrunfeldDocumento10 pagineChallenging The GrunfeldErickson Santos67% (3)

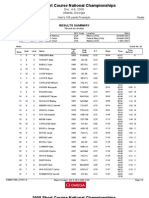

- C74A ResSummary 30 Heats Men 100 FreeDocumento3 pagineC74A ResSummary 30 Heats Men 100 FreeJohn LeskoNessuna valutazione finora

- Stephan Myburgh CVDocumento3 pagineStephan Myburgh CVapi-266135128Nessuna valutazione finora

- FootballDocumento36 pagineFootballAniketh ReddyNessuna valutazione finora

- Jeff Hardy CawDocumento6 pagineJeff Hardy CawchrislilgrockNessuna valutazione finora

- PPS PPC QDocumento5 paginePPS PPC QPaul GalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Ids Wwe 2K23Documento6 pagineIds Wwe 2K23elvigilante1492Nessuna valutazione finora

- ISU GP Internationaux de France de Patinage 2019 Judges Details Per SkaterDocumento6 pagineISU GP Internationaux de France de Patinage 2019 Judges Details Per SkaterPaula Ramos SolerNessuna valutazione finora

- Matika's Chess BlogDocumento73 pagineMatika's Chess BlogNicolás Diego GranelliNessuna valutazione finora

- 1997 US NAtional Golden GlovesDocumento9 pagine1997 US NAtional Golden GlovesStefanSchaeperNessuna valutazione finora