Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Beyond Orality

Caricato da

Ynon WeismanDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Beyond Orality

Caricato da

Ynon WeismanCopyright:

Formati disponibili

PSYCHOANALYTIC PSYCHOLOGY, 13(2), 177-203 Copyright 1996 Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Beyond Orality: Toward an Object Relations/Interactionist Reconceptualization of the Etiology and Dynamics of Dependency

Robert F. Bornstein, PhD

Gettysburg College

Although the classical psychoanalytic model of dependency contends that dependent personality traits are rooted in infantile feeding and weaning experiences and should be associated with various oral behaviors, empirical evidence supporting these assertions is weak. In this article I (a) review the empirical literature testing three key hypotheses regarding the dependency-orality relation, (b) briefly review extant object relations models of dependency, and (c) describe an integrated object relations/interactionist model of dependency that accounts for the entire range of behaviors exhibited by the dependent person but does not invoke the concept of orality to explain dependency-related personality dynamics. Evidence supporting the object relations/interactionist model is reviewed, and the clinical implications of this model are discussed.

In classical psychoanalytic theory, dependency is inextricably linked to the events of the infantile, oral stage of development (Freud, 1905). Frustration or overgratification during the oral stage is hypothesized to result in oral fixation, and in an inability to resolve the developmental issues that characterize this period (e.g., conflicts regarding dependency and autonomy). Thus, classical psychoanalytic theory postulates that the orally fixated (or oral dependent) person will (a) remain dependent on others for nurturance, guidance, protection, and support and (b)

Requests for reprints should be sent to Robert F. Bornstein, PhD, Department of Psychology, Gettysburg College, Gettysburg, PA 17325.

178

BORNSTEIN

continue to exhibit behaviors in adulthood that reflect the infantile oral stage (i.e., preoccupation with activities of the mouth, reliance on food and eating as a means of coping with anxiety). Early in his career, Freud (1908, p. 167) discussed in general terms the links between fixation and the development of particular personality traits, noting that "one very often meets with a type of character in which certain traits are very strongly marked while at the same time one's attention is arrested by the behavior of these persons in regard to certain bodily functions." Following Freud's (1905, 1908) initial speculations regarding the etiology and dynamics of oral dependency, several psychoanalytic writers (e.g., Abraham, 1927;Fenichel, 1945; Glover, 1925; Rado, 1928) extended the classical psychoanalytic model, suggesting that two variations in the infant's early feeding experience could lead to oral fixation and the development of oral dependent personality traits: (a) frustration during infantile feeding and weaning and (b) overgratification during the infantile feeding and weaning period. Goldman-Eisler (1948, 1950,1951) further refined the hypotheses of Abraham (1927), Fenichel (1945) and others, contrasting the personality characteristics of frustrated oral pessimists with those of overgratified oral optimists. Although subsequent studies failed to confirm the utility of the oral optimist-oral pessimist distinction (Masling, 1986; Masling & Schwartz, 1979), the concept of orality (along with the associated concepts of oral fixation and oral dependency) has continued to exert a strong influence on psychoanalytic theory (see Fisher & Greenberg, 1985; Parens & Saul, 1970). Not only has the concept of oral dependency had a profound influence on psychoanalytic models of personality development and psychopathology (Ainsworth, 1969; Eagle, 1984), but this concept has also played a central role in recent theoretical formulations regarding transference dynamics and the nature of the psycho therapeutic process (Blatt & Ford, 1994; Horowitz, 1988).1 During the past several decades, the focus of psychodynamic theory and research has shifted from a drive-based metapsychology derived from the classical psychoanalytic model to a more object relations-oriented approach wherein personality development and dynamics are conceptualized in terms of self-other interactions and internalized mental representations of the self and significant figures (see Galatzer-Levy & Cohler, 1993; Greenberg & Mitchell, 1983). Although the classical psychoanalytic model of dependency has to some degree been supplanted by more recent object relations frameworks, which describe the etiology and dynamics

Although several psychoanalytic writers have distinguished oral aggression from oral dependence (e.g., Fenichel, 1945; Glover, 1925), the vast majority of empirical studies in this area have assessed the affiliative, receptive iispects of orality (see Fisher & Greenberg, 1985; Masling & Schwartz, 1979). Thus, my review of the empirical literature of necessity focuses primarily on laboratory and field evidence related to oral receptivity and affiliative oral strivings.

BEYOND ORALITY

179

of dependent personality traits (Bornstein, 1992, 1993), the terms orality and oral dependence continue to be widely used in the psychoanalytic literature. Interestingly, the hypothesis that dependent personality traits in adults should be associated with various oral behaviors (e.g., eating, drinking, smoking) has continued to thrive, even among theoreticians and researchers who conceptualize personality development and dynamics primarily in object relations terms (see Greenberg & Mitchell, 1983;Silverman,Lachmann,&Milich, 1982;Tabin, 1985). Apparently, the notion that dependent behavior is linked with a preoccupation with food- arid mouth-related activities has become so widely accepted among psychoanalysts that this hypothesis is now "detached" from its classical psychoanalytic roots and continues to influence psychodynamic thinking even among those who reject many aspects of the drive model. In fact, even nonpsychoanalytic models of personality and psychopathology frequently utilize some variant of the orality concept to explain normal and pathological personality development (Bornstein, 1993, 1995). Although the orality-dependency link continues to be widely discussed among psychoanalytic theorists, clinicians, and researchers, evidence supporting this hypothesized relation is weak. The purpose of this article is to argue that the psychoanalytic concept of orality has outlived its usefulness and that we should now turn our attention to developing and refining theoretical models of dependency that do not attempt to link dependent behavior with oral behavior. Simply put, I argue that it is time for psychoanalysis to go beyond orality and develop a theoretical model of dependency that does not invoke the concepts of oral dependence and oral fixation. I first discuss the central hypotheses regarding the dependency-orality relation as this relation is described in classical psychoanalytic theory and then review the empirical literature testing these hypotheses. Next, I briefly review extant object relations models of dependency. Finally, I present a reformulated object relations/interactionist model of dependency which is consistent with research in this area, but which does not invoke the concept of orality to explain personality development and dynamics.

THE DEPENDENCY-ORALITY RELATION: HYPOTHESES DERIVED FROM THE CLASSICAL PSYCHOANALYTIC MODEL At least three testable hypotheses stem directly from the classical psychoanalytic model of oral dependency. First, this model predicts that high levels of dependency should result from variations in the infant's feeding and weaning experiences. Specifically, this model predicts that frustration (e.g., from abrupt weaning or the parents' use of a rigid and inflexible feeding schedule), or overgratification (e.g.,

180

BORNSTEIN

from an overly long nursing period) should produce high levels of dependency in offspring. Second, this model predicts that dependent behaviors and preoccupation with food- and mouth-related activities should covary in normal and clinical participants. Thus, individuals who show high levels of dependency should also exhibit various oral behaviors (e.g., thumbsucking, nail biting). In addition, to the extent that a person obtains a high dependency score on an objective or projective test, the person should also show high rates of food- and mouth-related imagery (if a projective test is used) or should report high rates of food- and mouth-related activities (if a self-report test is used). Third, the classical psychoanalytic model predicts that high levels of dependency should be associated with increased risk for psychological disorders that have a prominent oral component. Thus, dependent individuals should show increased risk for alcoholism, obesity, eating disorders (i.e., anorexia and bulimia), and tobacco addiction, insofar ^& each of these disorders is characterized by behaviors that reflect a preoccupation with oral activities. In the following sections I review empirical studies testing these predictions. Because there have been dozensif not hundredsof investigations in this area, I focus primarily on the most well-controlled, well-designed studies related to these three hypotheses.

Infantile Feeding and Weaning Experiences As Predictors of Later Dependency During the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, numerous researchers investigated the link between infantile feeding and weaning experiences and subsequent dependency levels in children, adolescents, and adults. The general approach used in these studies involved ob [aining retrospective reports of feeding and weaning behaviors from the mother and assessing the relation between these variables and participants' scores on some objective, projective, observational, or interview-based measure of dependency (Goldman-Eisler, 1948, 1950, 1951; Heinstein, 1963; Sears, 1963; Sears, Maccoby, & Levin, 1957; Sears, Rau, & Alpert, 1965; Sears, Whiting, Nowlis, & Sears, 1953; Sears & Wise, 1950; Stendler, 1954; Thurston & Mussen, 1951). Although there was some variation in the hypotheses tested in these studies, there was enough overlap among these hypotheses that they can be summarized in general terms. Researchers investigating the feeding/weaning-dependency relation predicted that exaggerated dependency needs in childhood, adolescence, or adulthood would result from (a) either a very long (i.e., overgratifying) or very brief

Although a comprehensive review of the empirical literature on the etiology and dynamics of dependency is beyond the scope of this article, such a review may be found in Bornstein (1993).

BEYOND ORALITY

181

(i.e., frustrating) nursing period, (b) a rigid (as opposed to flexible) feeding schedule, (c) bottle-feeding rather than breast-feeding, and (d) severe (i.e., abrupt) weaning. These investigations produced mixed results. Although Sears et al. (1953) found that mothers' reports of severity of weaning predicted subsequent teacher-rated dependency levels in both girls (r- .47) and boys (r- .39) in a sample of 40 nursery school children, Sears et al. (1957) were unable to replicate these results in a mixed-sex sample of 379 kindergarten children. In Sears et al.'s (1957) study, the children's dependency levels were unrelated to severity of weaning or rigidity of feeding schedule. Thurston and Mussen (1951) also found no relation between mothers' reports of several feeding and weaning variables and their adolescent children's dependency levels assessed via the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT). In this investigation, the relations between three feeding/weaning variables (i.e., age of weaning, rigidity of feeding schedule, breast- vs. bottle-feeding) and 30 TAT indices of dependency were assessed. This yielded 90 separate feeding/weaning-dependency comparisons. Four of the 90 comparisons were significant atp < .05, which is almost exactly what would have been expected on the basis of chance alone. Nonsignificant results were also obtained by Sears (1963), Sears etal. (1965), and Stenidler (1954). Heinstein's (1963) large-scale longitudinal study of the feeding/weaning-dependency link also failed to produce strong, consistent findings. Heinstein examined the relation of two feeding/weaning variables (i.e., breast- vs. bottle-feeding and length of the nursing period) to several indices of later dependency (i.e., preschool and late childhood interview ratings of dependency, TAT and Rorschach dependency scores) in a mixed-sex sample of 252 children. Of the 16 comparisons between predictor and criterion variables in Heinstein's study, only one produced results significant at p < .05: Breast-fed boys had significantly higher TAT dependency scores in late childhood (i.e., between ages 9 and 11) than did bottle-fed boys. Although studies in this area have generally produced results that do not support the hypothesis that infantile feeding and weaning experiences predict later dependency levels, one important methodological limitation of these investigations warrants mention. As noted earlier, studies in this area have almost invariably relied on mothers' retrospective reports of feeding and weaning practices. It is possible that the mother's ongoing interactions with her child influenced her memories of past mother-child interactions, so that memories of events such as "rigidity of feeding schedule" might not have been completely accurate in these studies. Moreover, even if mothers' memories for this information were accurate, self-presentation bias, need for approval, and numerous other factors might have compromised the accuracy of these reports. Thus, although studies to date have offered little support for an hypothesized feeding/weaning-dependency link, a rigorous test of this hypothesis would require a prospective investigation wherein parents'

182

BORNSTEIN

feeding and weaning practices are observed and rated as they occur and then these feeding and weaning variables are used to predict subsequent dependency levels in child, adolescent, or adult participants. Unfortunately, such a study has never been conducted.

Relation Between Dependency and Preoccupation With Food- and Mouth-Related Activities Several studies have tested the hypothesis that dependent persons would show higher rates of oral behaviors than nondependent persons (Beller, 1957; Blum & Miller, 1952; Heinstein, 1963; Juni & Cohen, 1985; Kline & Storey, 1980). Among the oral behaviors tested in these investigations were thumb-sucking (Beller, 1957; Heinstein, 1963), nail biting and pen chewing (Kline & Storey, 1980), exhibiting "nonpurposive mouth movements" during school (Blum & Miller, 1952), preferring oral sex (i.e., cmnilingus and fellatio) over other forms of sexual activity (Juni & Cohen, 1985), and playing a wind instrument (as opposed to another type of musical instrument) in a school orchestra (Kline & Storey, 1980). These studies involved both children and adults and utilized participants from clinical as well as nonclinical samples. In general, these studies failed to find any strong or consistent relations between participants' scores on objective, projective, or interview-based dependency measures and their score s on indices of preoccupation with oral activities. In those few studies wherein statistically significant relations between participants' orality and dependency scores were found (e.g., Kline & Storey's, 1980, assessment of the link between objective dependency scores and pen-chewing frequency in college students), the magnitudes of these relations were quite small. Moreover, as Masling (1986; Masling & Schwartz, 1979) pointed out, these observed dependency-orality relations may well have been due to a third factorimmaturitywhich underlied the participants' high dependency scores as well as their high rates of such oral behaviors as thumbsucking. Consistent with the findings of Blum and Miller (1952), Juni and Cohen (1985), and others, both Beckwith (1986) and Mills and Cunningham (1988) failed to find significant relations among various indices of oral behaviors in samples of community and college student participants. Factor-analytic studies assessing the intercorrelations of dependent and oral traits also produced results which do not support the hypothesis that these traits would covary in viirious participant groups. Barnes (1952), Gottheil and Stone (1968), Jamison and Comrey (1968), Kline (1973), and Lazare, Klerman, and Armor (1966, 1970) all assessed the relation between participants' self-reports of the frequency with which they exhibited dependent behaviors (e.g., help-seeking) and the frequency with which they exhibited various oral behaviors (e.g., nail biting), using factcr-analytic and cluster-analytic approaches. In each of these

BEYOND ORALITY

183

studies, the magnitude of the dependency-orality correlation was small (e.g., r .21; Kline, 1973), and in most cases these observed relations failed to reach statistical significance. As was the case for behavioral studies of the dependency-orality link (e.g., Blum & Miller, 1952), these relatively small dependency-orality relations were likely due, in whole or in part, to the presence of a third underlying factor such as immaturity (Masling & Schwartz, 1979) or trait anxiety (Bornstein, 1992, 1993) that underlied participants' dependency-related behaviors as well as their oral behaviors. Finally, three studies have assessed the relation between the frequency of dependency-related imagery and the frequency of food- and mouth-related imagery produced by adolescent and adult participants on the Rorschach test. All three studies used Masling, Rabie, and Blondheim's (1967) Rorschach Oral Dependency scoring system to assess participants' dependency-related and food/mouth-related Rorschach responses. The results of these investigations were mixed. Although Bornstein, Manning, Krukonis, Rossner, and Mastrosimone (1993) found a significant positive correlation between these two Rorschach variables (r - .37) in a mixed-sex sample of college students, both Bornstein and Greenberg (1991) and Shilkret and Masling (1981) found no relation whatsoever between participants' dependency and food/mouth-related imagery scores in psychiatric inpatients and college student participants. In fact, Shilkret and Masling obtained a small (albeit nonsignificant) inverse correlation (r = -.06) between Rorschach dependency and food/mouth-related imagery scores in their mixed-sex college student sample. When the dependency-food/mouth-related imagery correlations obtained in these three investigations are pooled using meta-analytic techniques (Rosenthal, 1984), the overall relation between these variables is .09.

Dependency As a Predictor of "Oral" Psychopathology Most correlational studies assessing the relation between dependency and alcoholism suggest that alcoholic participants obtain higher dependency scores than do nonalcoholic controls (Bertrand & Masling, 1969; Conley, 1980; Craig, Verinis, & Wexler, 1985; Poldrugo & Forti, 1988). However, three studies produced nonsignificant results in this area, finding no relation between dependency levels and alcohol use (Blane & Chafetz, 1971; Evans, 1984; McCord, McCord, & Thurber, 1962). Of course, these correlational studies do not address the question of whether dependency actually predisposes individuals to alcoholism. An equally plausible interpretation of these results is that the onset of alcoholism somehow causes an increase in dependent feelings, thoughts and behaviors. Longitudinal studies of the dependency-alcoholism link clearly support the latter hypothesis. Jones (1968), Kammeier, Hoffman, and Loper (1973), and Vaillant (1980) conducted prospective studies of the dependency-alcoholism rela-

184

BORNSTEIN

tion and obtained highly consistent results. In each of these investigations, premorbid dependency levels did not predict subsequent risk for alcoholism. However, Vaillant found that a variety of dependency-related traits (e.g., passivity, pessimism, self-doubt) showed significant increases following the onset of alcoholism in his sample of male participants who were assessed periodically on a variety of personality and psy:hopathology measures between the ages of 20 and 50. As is the case far studies of the dependency-alcoholism link, studies of the dependency-obesity relation have produced mixed results. Although several studies found that obese participants obtain significantly higher objective and projective dependency scores :han normal-weight participants (Masling et al., 1967; Mills & Cunningham, 1988: Weiss & Masling, 1970), other similar experiments found no relation between dependency and obesity (Black, Goldstein, & Mason, 1992; Bornstein & Greenberg, 1991; Keith & Vandenberg, 1974). Moreover, as Masling and Schwartz (1979) pointed out, there are several methodological problems with studies of the dependency-obesity link. Most important, studies in this area have generally failed to control for overall level of psychopathology, so that observed dependency-obesity relations in these investigations might reflect, in whole or in part, the effects of higher overall levels of psychopathology in obese participants relative to controls. In contrast to studies of the dependency-obesity link, most studies of the dependency-eating disorders relation have compared the frequency of dependent personality disorder (DPD) symptoms in eating-disordered participants and noneating-disordered controls (Bornstein, 1993). Although these investigations have generally found that anorexic and bulimic participants show higher rates of DPD symptoms and diagnoses than do matched control participants (Jacobson & Robins, 1989; Lenihan & Kirk, 1990; Levin & Hyler, 1986; Wonderlich, Swift, Slotnick, & Goodman, 1990; Zimmerman & Coryell, 1989), these investigations also found that eating-disordered participants show elevated rates of several other personality disorder diagnoses. For example, although 32% of the eating-disordered participants in Wonderlich et al.'s inpatient sample met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed., Rev.; American Psychiatric Association, 1987) diagnostic crkeria for DPD, 32% of these participants also met the diagnostic criteria for avoidant personality disorder, 25% received borderline personality disorder diagnoses, 23% received histrionic personality disorder diagnoses, and 18% received diagnases of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Levin and Hyler (1986) also found that several other personality disorders were at least as common as DPD in a sample of eating-disordered psychiatric outpatients. Thus, although it is clear that there is some relation between dependency and eating disorders, the specificity of this relation remains open to question, and it is likely that observed dependency-eating disorder links simply reflect the greater overall levels of psychopathology typically found in eating-disordered participants relative to controls (Bornstein, 1993). In addition, as was the case for studies of the

BEYOND ORALITY

185

dependency-alcoholism link, the causal relation between dependency and eating disorder symptomatology remains open to question; it may be that increases in dependent feelings, thoughts and behaviors follow, rather than precede, the onset of eating disorder symptoms. The only oral psychopathology that has clearly been shown to be related to underlying dependency needs is tobacco addiction. Not only do cigarette smokers show significantly higher dependency levels than nonsmokers (Jacobs et al., 1966; Jacobs et al., 1965; Veldman & Bown, 1969), but studies have also demonstrated that there is a significant positive correlation between level of dependency and smoking frequency (Jacobs & Spilken, 1971; Kline & Storey, 1980). Vaillant (1980) further found that level of dependency assessed at age 20 predicted subsequent smoking frequency in a sample of 184 male college graduates. Vaillant's results suggest that dependency may actually predispose individuals to cigarette smoking, rather than being a correlate or consequence of tobacco addiction. Although Vaillant's (1980) results are consistent with the hypothesis that dependent persons rely on food- and mouth-related activities to cope with anxiety, an alternative interpretation of these results is that the increased rates of smoking observed in the dependent men in Vaillant's sample reflect dependent persons' increased susceptibility to social influence. Specifically, it may be that the dependent men in Vaillant's sample were more strongly influenced than nondependent men by peer pressure to smoke during adolescence. In this context, it is noteworthy that the participants in this sample typically initiated smoking during the 1950s, before strong cautionary messages regarding the dangers of cigarette smoking were commonplace. Of course, the social pressures surrounding tobacco use have changed considerably during the past several decades and, given the dependent individual's desire to please figures of authority (e.g., parents, teachers; see Bornstein, 1992) and the strong antismoking messages conveyed by many figures of authority today, it is entirely possible that a longitudinal study of the dependency-smoking link involving today's college students would yield precisely the opposite results from those obtained by Vaillant. OTHER LIMITATIONS OF THE CLASSICAL PSYCHOANALYTIC MODEL Clearly, the results of studies assessing the dependency-orality relation do not offer strong support for the classical psychoanalytic model of dependency. First and foremost, empirical studies do not support the hypothesis that dependent traits and behaviors may be traced to variations in infantile feeding and weaning experiences. Second, although studies of the relation between dependency and preoccupation with oral activities and studies of the relation between dependency and various oral psychopathologies have produced mixed results, evidence supporting these hypothesi2,ed relations is, at best, weak, and, as noted earlier, this evidence is

186

BORNSTEIN

participant to alternative interpretations. To the extent that links between dependency and oral activities and between dependency and risk for oral psychopathologies actually exist, these links most likely reflect immaturity and insecurity on the part of the dependent person and a general elevation in risk for many forms of psychopathologynot only those related to food and oral activitiesin persons who show exaggerated dependency needs. Although many empirical studies of the dependency-orality link are methodologically flawed, it is important to note that in most cases these flaws would tend to inflate observed dependency-orality relations. Thus, those dependency-orality relations that have been obtained in laboratory and field studies likely represent overestimates of the degree to which dependency levels are actually associated with oral behaviors and psychopathologies. Taken together, findings from 50 years of research assessing the dependency-orality link indicate that there are few (if any) strong or consistent relations between these variables. Although the aforementioned findings, in and of themselves, raise serious questions about the validity and utility of the classical psychoanalytic model of dependency, two other limitations of this framework also warrant brief mention here because these limitations turn out to have important implications for other theoretical models. First, a fundamental tenet of the orality model is that dependency is invariably associated with passivity. This assumption pervades the writings of early psychoanalytic theorists, and is illustrated nicely by Fenichel's (1945, p. 391) assertion that "if a person remains fixated to the world of oral wishes, he will, in his general behavior present a disinclination to take care of himself, and require others to look after him." Abraham (1927), Glover (1925), Rado (1928), and others offered similar arguments regarding the dependency-passivity link. However, these assertions are not supported by research on the psychodynamics of dependency. In fact, studies in this area indicate that the dependent person often behaves in an active, assertive manner, particularly when he or she believes that behaving in this manner will s trengthen ties to a potential nurturer or caretaker (e.g., parent, teacher, physician, therapist). For example, studies show that dependent persons ask for feedback on psychological tests more readily than do nondependent persons (Juni, 1981) and ask for help when attempting to solve difficult problems in the laboratory more frequently than do nondependent persons (Shilkret & Masling, 1981). Furthermore, dependent persons make more demands upon physicians and therapists (e.g., requests for "emergency" sessions) than do nondependent persons (Emery & Lesher, 1982). Although dependent persons often yield to nondependent persons in interpersonal negotiations, they show the opposite pattern of behavior (i.e., decreased yielding relative to nondependent persons) when they believe that refusing to yield will please a figure of authority (Bornstein, Masling, & Poynton, 1987). In short, although dependency is associated with help-seeking behavior and a desire to obtain and maintain nurturant, supportive relationships, dependency is not invariably

BEYOND ORALITY

187

associated with passivity. The degree to which the dependent person behaves in a passive, acquiescent manner or in an active, assertive manner is determined primarily by the demands and situational constraints that characterize a given situation (see Bornstein, 1995, for a discussion of this issue). A second limitation of the classical psychoanalytic model of dependency is its strong emphasis on the negative consequences of dependent personality traits. Psychoanalytic theorists have been virtually unanimous in their contention that dependency represents a flaw or deficit in functioning. To be sure, the empirical literature confirms that high levels of dependency are in fact associated with a number of negative consequences (e.g., increased risk for certain forms of psychopathology, increased risk for physical disorders; see Bornstein, 1992, 1993). However, dependency is also associated with such positive traits as the ability to infer accurately the attitudes and beliefs of other people (Masling, Johnson, & Saturansky, 1974), a desire to perform well in classroom settings (Bornstein & Kennedy, 1994), a willingness to seek treatment quickly when symptoms appear (Greenberg & Fisher, 1977), and a tendency to comply rigorously with medical and psychological treatment regimens (Poldrugo & Forti, 1988). Instead of simply being a problem, deficit, or flaw in functioning, as many theoreticians and researchers have suggested, dependency is associated with both positive and negative qualities. TOWARD AN OBJECT RELATIONS/INTERACTIONIST RECONCEPTUALIZATION OF THE ETIOLOGY AND DYNAMICS OF DEPENDENCY Given the lack of firm empirical support for an hypothesized dependency-orality link, coupled with other important limitations of the orality model, it is time to turn our attention to developing alternative theoretical models of dependency. As I have pointed out elsewhere (Bornstein, 1992, 1993), object relations theory provides a particularly fruitful starting point for these efforts. In the following sections I briefly review existing object relations models of dependency and present a reformulated object relations/interactionist model that accounts for the entire range of behaviorspassive and active, adaptive, and maladaptivethat are exhibited by the dependent person.3 Extant Object Relations Models of Dependency Despite the fact that object relations models of personality and psychopathology almost invariably attribute great importance to the infant-caretaker relationship as

A detailed review of extant object relations models of dependency is provided by Greenberg and Mitchell (1983).

188

BORNSTEIN

a primary determinant of personality development and dynamics, the concept of dependency has net played as central a role as one might expect in these models. In many object relations frameworks, dependency is discussed primarily in terms of the infant's progression from more-or-less complete reliance on the primary caretaker for nurturance and support to a more autonomous state wherein the child is increasingly capable of meeting physiological (and psychological) needs on his or her own (see Eagle, 1984; Greenberg & Mitchell, 1983; Greenspan, 1989; Mahler, Pine, & Bergman, 1975). Beginning with Freud's (1924, p. 168) recognition that the "course of childhood development leads to an ever-increasing detachment from the parents," many psychodynamic thinkers have discussed the consequences of the child's struggle to resolve the ostensibly conflicting needs for care and nurturance on the one hand and autonomy and self-directedness on the other (see Silverman et al., 1982, for a detailed discussion of this issue). In this context, both Jacobson (1964) and Mahler et al. (1975) argued (albeit in somewhat differen t terms) that infants and young children experience an ongoing tension between the struggle for individuation and the wish to re-merge with the omnipotent, omniscient caretaker of infancy. As Galatzer-Levy and Cohler (1993), Greenberg and Mitchell (1983), and Silverman et al. (1982) pointed out, a variety of psychological phenomena reflect this ongoing tension between the individual's strivings for separation and independence and the desire to regress and re-merge with the primary caretaker of infancy. These phenomena include (but are not limited to) the experience of romantic love, the use of psychotropic drugs to quell anxiety, and the strong identification that many persons develop with members of various religious and social groups. Approaching this issue from a very different perspective, Fairbairn (1952) contended that heal thy development does not require a high degree of independence from others, but instead entails a progression from complete dependence upon the parents for biological and psychological gratification to a state of flexible interdependence wherein the individual is capable of experiencing the self as autonomous and self-directed, while simultaneously remaining connected toand intimate withother people. Using somewhat different terminology, theorists as diverse as Homey (1945), Klein (1945), Sullivan (1947), Winnicott (1965), Guntrip (1961), Kohut (1977), and Kernberg (1975) have discussed the central role that early relationships (especially early relationships with the primary caretaker) play in the development of an autonomous sense of self and in the evolution of the individual's capacity for mature intimacy. Moreover, the work of Kohut and others makes clear that although early dependence upon the primary caretaker plays a key role in the construction of the self-representation, the emergence of a cohesive sense of self ultimately comes to play a central role in the individual's capacity for connectedness, intimacy, and healthy interdependence (see Eagle, 1984; Galatzer-Levy & Cohler, 1993).

BEYOND ORALITY

189

The critical importance of the child's transition from dependency and helplessness to autonomy and interdependence as a factor in normal and pathological personality development was also echoed in the attachment theories of Bowlby (1969,1980), Ainsworth (1969) and others (e.g., Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985). These theories extended earlier object relations conceptualizations of dependency by acknowledging the role that mental representations of the self and other people play in the etiology and dynamics of dependent personality traits. As Main et al. (1985) pointed out, a central component of the dependent personality orientation is a belief on the part of the dependent person that other people will be available to offer guidance, protection, and support when he or she is confronted with stressful events or challenging situations. In this respect, attachment theorists go beyond many early object relations models by making explicit the idea that mental representations of the self, other people, and self-other interactions (i.e., internalized working models of the self and others) play a central role in the acquisition and development of dependent traits, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors (see also Bowlby, 1969, 1980).4 In recent years, Blatt's (1974, 1991) theoretical framework has been the most influential object relations model of dependency. Integrating concepts from object relations theory and self psychology with ideas and findings from research on cognitive development, Blatt and his colleagues (e.g., Blatt & Shichman, 1983) have argued that dependent personality traits in children and adults result primarily from the internalization of a mental representation of the self as weak and ineffectual. Developmental research on parent-child interactions confirms that parenting styles that lead the child to view the self as powerless and weak do in fact lead to high levels of dependency in offspring (Blatt & Homann, 1992), a conclusion that has been echoed by researchers who conceptualize dependency within the context of attachment theory and invoke the concept of internalized working models of self and others to describe personality development and dynamics (Main et al., 1985).

Although many object relations models suggest that dependent traits and behaviors are rooted in a representation of the self as powerless and ineffectual, it is important to note that the construction of a helpless self-representation is not the only means through which dependent traits and behaviors may assume a prominent role in inter- and intrapersonal functioning. For example, dependent behaviors can serve as a defense against unrequited narcissistic impulses (Kohut, 1977) and as a means of bolstering the self-esteem of significant others whose identity centers around providing nurturance, care, and support to the dependent person (Kernberg, 1975). Alternatively, dependent behavior can stem from strategic self-presentation needs rather than from high levels of underlying dependency strivings (Jones & Pittman, 1982), especially in those situations wherein exhibiting dependent behavior appears to be an effective means of manipulating and controlling the behavior of others (Bornstein, 1993). Thus, although it is clear that a representation of the self as powerless and ineffectual is an important factor in the etiology and development of dependent personality traits, it is important to keep in mind that other disposition^ and situational variables may also play a significant role in the inter- and intrapersonal dynamics of dependency.

190

BORNSTEIf i

As the child internalizes a mental representation of the self as weak and ineffectual, the child (a) looks to others to provide protection and support (Bornstein, 1993), (b) becomes preoccupied with fears of abandonment (Blatt, 1974), (c) behaves in a dependent, help-seeking manner (Bornstein, 1992), (d) shows increased risk for depression and other anaclitic psychopathologies (Blatt & Homann), and (e) develops a predisposition to several forms of physical illness, including heart disease and cancer (Blatt, Cornell, & Eshkol, 1993). Blatt's (1974, 1991) contention that the self-representation plays a central role in the etiology and dynamics of dependency provides an overarching conceptual framework that allows for an integration of empirical research on dependency with concepts and principles derived from object relations theory and self psychology (see, e.g., Blatt & Ford, 1994; Blatt & Homann, 1992; Blatt & Shichman, 1983). During the past several years I have utilized the central tenets of Blatt's (1974, 1991) theoretical framework to elaborate and refine an object relations/interactionist model of dependency which brings together a number of important theoretical and empirical findings in this area. Preliminary discussions of this object relations/interactionist model may be found in Bornstein (1992, 1993, 1995). In the following section I briefly describe the most important features of the model.

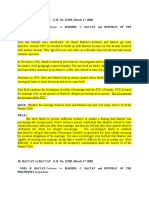

An Object Relations/interactionist Perspective on Dependency Any integrated conceptual model of dependency must begin with the recognition that there are four central components to a dependent personality orientation: (a) motivational (i.e., i marked need for guidance, approval, and support from others), (b) cognitive (i.e., a perception of the self as powerless and ineffectual, along with the belief that others are comparatively powerful and can control the outcome of situations), (c) affective (i.e., a tendency to become anxious and fearful when required to function independently, especially when the products of one's efforts are to be evaluated by others), and (d) behavioral (i.e., a tendency to seek help, support, approval, guidance, and reassurance from others). With these four components in mind, it is possible to specify the developmental antecedents of dependent personality traits and to explore the ways that dependency-related cognitions, motivations, behaviors, and emotional responses interact to influence the functioning of the dependent person in various situations and settings. The central elements of an object relations/interactionist model of dependency are summarized in Figure 1. As Figure 1 shows, the etiology of individual differences in dependency lies primarily in two areas: overprotective, authoritarian parenting and se>.-role socialization (Bornstein, 1993, 1994). Overprotective, authoritarian parenting fosters dependency in children by preventing the child from

BEYOND ORALITY

1 91

Overprotective, Authoritarian Parenting; Sex Role Socialization

^ Cognitive Effects: Representation of self as L powerless and ineffectual; Belief that others are powerful and in control

Motivational Sequelae: Desire to obtain and maintain nurturant, supportive relationships Behavioral Sequelae: Suggestibility, yielding, I 'A help-seeking, compliance ^Affective Sequelae: Performance anxiety, fear of abandonment, fear of negative evaluation

Good Social Skills; Interpersonal Sensitivity

Successful in Eliciting Help; Supportive Relationships Maintained Low Anxiety; Low Stress

Poor Social Skills; Lack of Interpersonal Sensitivity Rejection by Peers; Supportive Relationships Not Maintained High Anxiety; High Stress

V' Risk tor Depression

Immune System Deficits

Risk for Physical Illness

FIGURE 1 An object relations/interactionist model of dependency.

developing the sense of mastery and autonomy that follows successful learning experiences (see McCord et al., 1962; Sroufe, Fox, & Pancake, 1983). Although either parental overprotectiveness or parental authoritarianism can lead the child to perceive himself or herself as incapable of functioning independently, a perception

192

BORNSTEIN

of the self as weak and ineffectual is particularly likely to result when parents exhibit both of these traits (Baumrind, 1971). Parental overprotectiveness and authoritarianism play a key role in the construction of a representation of the self as powerless and weak. Sex-role socializ ation practices may further foster the development of a dependent self-representation in girls, insofar as traditional sex-role socialization practices encourage passivity, acquiescence, and dependency in girls more strongly than in boys (Spence & Helmreich, 1978). Not surprisingly, studies wherein dependency levels are assessed via self-report tests almost invariably find that female participants obtain significantly higher dependency scores than male participants (Bornstein et al., 1993), with sex differences in dependency appearing by middle childhood and remaining stable through most of adult life (Bornstein, 1992). Clearly, cultural factors play a role in the etiology of dependency, althoughin contrast to the effects produced by overprotective, authoritarian parentingthese sex-role socialization effects foster dependency in women far more strongly than in men.5 In addition to fostering the development of a representation of the self as weak and ineffectual, overprotective, authoritarian parenting will encourage the child to believe that he or she must rely on others for guidance, protection, and support. Because early experiences with the parents create particular expectations for future interpersonal relationships (Blatt & Homann, 1992; Main et al., 1985), parental overprotectiveness will lead to an expectation on the part of children that they will be nurtured and cared for by others. Similarly, parental authoritarianism will lead children to believe that the way to maintain good relationships with others is to acquiesce to their requests, expectations, and demands (Ainsworth, 1969; Baumrind, 1971). Thus, the model summarized in Figure 1 suggests that cognitive structures (i.e., self- and object-representations) that are formed in response to early experiences within the family w ill influence the motivations, behaviors, and affective responses of the dependent person in predictable ways. A perception of oneself as powerless and ineffectual will, first and foremost, have motivational effects. A person with

5 In this context, it is i uportant to note that parenting style and sex-role socialization practices are not completely independent A great deal of sex-role socialization takes place within the family, and it is likely that global indices of parenting style predict important aspects of a parent's sex-role socialization practices. For example, research indicates that highly authoritarian parents tend to encourage traditional sex-role-related behaviors in children to a greater degree than do less authoritarian parents (see Baumrind, 1971). This turns out to have very different implications for boys and girls. In young girls, authoritarian parenting practices and traditional sex-role socialization experiences will tend to work in concert to promote dependent behavior. In young boys, the interactive effects of parenting practices and sex-role socialization experiences are more complicated in that authoritarian parents will be likely to encourage sex-role-type i behaviors in boys, while simultaneously engaging in the kinds of child-rearing practices that discourage independent decision-making and autonomous behavior.

BEYOND ORALITY

193

such a self-concept will be motivated to seek guidance, support, protection, and nurturance from other people. These self-concept-based motivations in turn produce particular patterns of dependent behavior: The person who is highly motivated to seek the guidance, protection, and support of others will behave in ways that maximize the probability that they will obtain the protection and support that they desire. Finally, a representation of the self as powerless and ineffectual will have important affective consequences (e.g., fear of abandonment, fear of negative evaluation). Although cognitive structures produced in response to early parenting and socialization experiences mediate the motivations, behaviors, and affective responses of the dependent person, affective responses ultimately come to play a particularly important role in the dynamics of dependency. As Figure 1 shows, affective responses systematically influence the cognitions, motivations, and behaviors of the dependent person. Specifically, dependency-related affective responses (e.g., performance anxiety) strengthen and reinforce dependency-related motivations (e.g., need for support). In other words, when an event or situation stimulates a dependency-related affective response, the individual's dependencyrelated motivations will increase. Similarly, when a dependency-related affective response is stimulated, dependent behavior is more likely to be exhibited. Most important, though, dependency-related affective responses strengthen and reinforce the dependent person's belief in his or her own ineffectiveness. Consequently, a feedback loop is formed wherein affective responses that initially resulted from particular beliefs about the self and other people ultimately come to reinforce and strengthen those very same beliefs. Similar feedback loops characterize the affect-motivation and affect-behavior relations. The model summarized in Figure 1 provides a useful framework for understanding why dependency is associated with active, assertive behavior in certain situations. As noted earlier, empirical studies confirm that the dependent person will behave in an assertive manner if there is the belief that doing so can strengthen ties to potential nurturers and protectors. The results of studies in this area further suggest that one central goal underlies much of the dependent person's interpersonal behavior: obtaining and maintaining nurturant, supportive relationships (see Millon, 1981). This goal has been referred to as the core motivation of the dependent person (Bornstein, 1992, 1993), and it represents the link between dependency-related passivity and dependency-related assertiveness. Simply put, dependent individuals exhibit behaviors that maximize their chances of obtaining and maintaining supportive relationships. When passive, compliant behavior seems likely to achieve this goal, the dependent person chooses to behave in a passive manner. When active, assertive behavior seems more likely to achieve this goal, the dependent person becomes active and assertive. Exhibiting passive, compliant behavior in certain contexts and active, assertive behavior in others merely represents an attempt on

194

BORNSTEIN

the part of the dependent person to fulfill their underlying goal of cultivating relationships with nurturant, caretaking figures. The hypothesis that the dependent person* s core motivation is to obtain and maintain nurturant, supportive relationships is consistent with the finding that overprotective, authoritarian parenting predicts subsequent dependency levels in children, adolescents, and adults. Figure 1 illustrates the connection between early parenting experiences and the core motivation of the dependent person. Working backwards through the model, it is clear that the beaaviors exhibited by the dependent person in various contexts and settings reflect the core motivation of the dependent person. This core motivation may be traced to beliefs regarding the self and other people, which in turn may be traced to particular experiences within the family. Because the core motivation of the dependent person is to obtain and maintain nurturant, supportive relationships, the degree to which a dependent individual exhibits good social skills and is sensitive to interpersonal cues will have important implications for the; long-term consequences of dependency (see Bornstein, 1992, and Masling, 1986, for discussions of the dependency-social skills and dependency-interpersonal sensitivity relations). In Figure 11 have divided the population of dependent persois into those with good social skills and those with poor social skills to illustrate the effects of this variable on the long-term consequences of dependency. As Figure 1 shows, good social skills should be associated with success in eliciting social support and with the ability to cultivate nurturant, supportive relationships. To the extent that dependent persons are able to obtain and maintain such supportive relationships, anxiety and stress should be minimized. In a sense, this represents the best possible long-term consequence of dependency. However, two less-than-positive consequences of this long-term outcome are also worth mentioning i n this context. First, it is important to note that the dependent person in this situation has, in effect, recapitulated the earlier parent-child dynamic that led to his or her dependency in the first place. In other words, the dependent person has sought out and obtained a guide/protector who functions much like the overprotective, authoritarian parent of infancy and early childhood. Second, insofar as the presence of a nurturant, supportive other serves as an anxiety and stress-reducer for the dependent person, the presence of a nurturer/protector will serve to reinforce the dependent individual's helpless self-concept. Put another way, to the extent that the dependent person continues to rely on other people for protection and support, the dependent person will continue to believe that the self cannot function without the protection and help of others. The dependent person with less effective social skills will not be as successful in cultivating nurturant, supportive relationships. As Figure 1 shows, the absence of supportive relationships will lead to increased anxiety and stress in the dependent person. This increased anxiety and stress has implications for both psychological and physical adjustment. With respect to psychological functioning, high levels of

BEYOND ORALITY

195

stress and anxiety will lead to increased risk for depression in the dependent person (Overholser & Freiheit, 1994). With respect to physiological functioning, high levels of anxiety and stress will lead to diminished immunocompetence in the dependent individual, ultimately leading to increased risk for various physical illnesses that are mediated by the immune system (Blatt et al., 1993). Ironically, the onset of physical or psychological illness will reinforce even further the dependent person's helpless self-concept. Numerous studies have shown that the onset of illness is often followed by increases in dependent, help-seeking behavior (Bornstein, 1993). To the extent that the dependent person assumes the "sick role" following the onset of physical or psychological illness, he or she will perceive the self as powerless, ineffectual, and dependent on others for protection and support will increase. Thus, it is ironic thatalthough interpersonal sensitivity and social skills may play a key role in determining the long-term outcome of dependencyboth of the outcomes depicted in Figure 1 ultimately lead to the same end: reinforcement of the dependent person's helpless self-concept. In a sense, this conclusion is not surprising. Numerous studies have demonstrated that individuals typically behave (and process self-referent information) in such a way as to protect and reinforce pre-existing beliefs about the self and other people (Greenwald, 1980). In this context, Caspi, Bern, and Eilder (1989) suggested that dependency as an interactional style may well be even more self-perpetuating than [other personality styles] because dependent individuals are positively motivated to select and construct environments that sustain their dependency. ... dependent persons recruit and attach themselves to others who will continue to provide the nurturance and support they seek. ... these individuals become increasingly skilled at evoldng from others those nurturing responses that reinforce their dependency, (p. 395) Similar arguments regarding the self-perpetuating nature of dependency have been offered by Birtchnell (1988) and Millon (1981). CONCLUSIONS In light of the fact that evidence supporting an orality model of dependency is, at best, equivocal, the question remains: Why have the terms orality and oral dependency persisted in the psychoanalytic literature? Several factors underlie psychoanalysts' continued use of these terms. First, the terms orality and oral dependency have been used by psychoanalysts for nearly 100 years. There is a long tradition underlying the use of these terms, and the concept of orality is very much a part of the culture and history of psychoanalysis. Second, as Masling (1986) pointed out, the concept of orality provides a rich and evocative vocabulary for theorists and

196

BORNSTEIN

clinicians to use when describing dependency-related personality dynamics. To some extent, these terms have persisted simply because they provide a compelling language for describing the behavior of patients in clinical settings. Finally, as numerous researchers have noted, many psychoanalytically-oriented clinicians are resistant to altering their theoretical conceptualizations based on the results of controlled empirical studies (Fisher & Greenberg, 1985). Thus, clinicians have been able to describe many examples of clinical interactions that appear to support the concept of orality, although as Masling and Cohen (1987) pointed out, much of this clinical evidence reflects a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy wherein clinicians selectively attend to (and remember) only those patient-therapist interchanges that support their a priori beliefs. Although studies of the feeding/weaning-dependency link, studies of the covariation of dependent and oral behaviors, and studies of the relation between dependency and various oral psychopathologies have not provided compelling support for an orality conceptualization of dependency, it is not the case that the orality model has yielded uniformly negative results. As Fisher and Greenberg (1985) noted, several hypotheses regarding the psychody namics of oral dependency have received at least moderate empirical support. Most importantly, the hypothesized relation between dependency and depression, first described by Abraham (1927) and others r as been confirmed repeatedly in laboratory and field investigations (Blatt & Homann, 1992; Bornstein, 1992). In general, empirical research on dependency has supported a number of subsidiary hypotheses that stem from the classical psychoanalytic model (e.g., the dependency-depression link), but has not offered strong support for the key hypotheses that underlie the orality-dependency relation (e.g., the feeding/weaning-dependency link). It may be that tine most fruitful approach for testing hypotheses regarding the orality-dependency relation is to utilize experimental approaches that allow researchers to assess whether manipulating an individual's underlying dependency levels produces measurable changes in food- and mouth-related fantasies, thoughts, motivations, and behaviors. Silverman's (1983; Silverman et al., 1982) subliminal psychodynamic activation paradigm would be an obvious starting point for experimental work in this area, although recent studies have delineated several other potentially useful approaches to manipulating underlying dependency needs in clinical and nonclinical participants (see, e.g., Bornstein, Rossner, Hill, & Stepanian, 1994). In any case, studies of the orality-dependency link conducted to date have tended to employ correlational designs (Bornstein, 1993; Masling & Schwartz, 1979); future research in this area should begin to utilize experimental manipulations that allow researchers to draw firmer conclusions regarding causal relations between orality and dependency, if future studies suggest that such relations do in fact exist. Leaving aside unresolved questions regarding the orality-dependency link, it is clear that in several respects an integrated object relations/interactionist model of

BEYOND ORALITY

197

dependency has greater heuristic value than the traditional orality model. Most importantly, this model accommodates two key sets of results that are not easily accounted for by the orality model: (a) findings which indicate that dependent persons often behave in an active, assertive manner in order to obtain and maintain nurturant, supportive relationships; and (b) findings which suggest that high levels of dependency are associated with positive, adaptive behaviors as well as problematic, maladaptive behaviors in clinical and nonclinical participants. Beyond this, the object relations/interactionist model's assertions regarding the antecedents of dependent personality traits (i.e., overprotective, authoritarian parenting and dependency-fostering sex-role socialization practices) are consistent with a number of empirical findings in this area. In addition, the model specifies some key causal relations among dependency-related cognitions, motivations, behaviors, and emotional responses and helps to explain the causal links between high levels of dependency and risk for various forms of psychological and physical pathology. Although the object relations/interactionist model was developed very recently (Bornstein, 1992, 1993) and many aspects of this model await empirical verification, recent findings from laboratory and field studies of dependency offer reasonably strong support for the model. For example, the hypothesis that poor social skills and an absence of social support leads to increased risk for depression in dependent persons was; confirmed by Overholser and Freiheit (1994). Similarly, the hypothesis that dependency and interpersonal stress combine to result in diminished immunocompetence and increased risk for physical illness was confirmed by Blatt et al.'s (1993) findings regarding the dependency-stress-illness link. The object relations/interactionist model's contention that cognitive structures (i.e., self and object representations) play a key role in determining dependencyrelated motivations, behaviors, and affective responses is consistent with recent studies of the interpersonal dynamics of dependency in clinical and nonclinical participants (Bornstein, 1994). Finally, the model's assertion that situational variables are an important determinant of dependency-related passivity and dependency-related assertiveness has been confirmed by a number of recent findings in this area (Bornstein, 1995). It would be premature to speculate unduly regarding the clinical implications of the object relations/interactionist model of dependency until this model receives unequivocal empirical support. However, several issues related to the clinical implications of the model warrant brief discussion in this context. For example, the object relations/interactionist model suggests that insight-oriented psychotherapy with dependent persons should focus, at least in part, on altering problematic beliefs regarding the self and other people. As several clinicians have noted, the strong transference reactions exhibited by many dependent patients provide numerous opportunities to explore (and eventually challenge) the patient's beliefs regarding his or her powerlessness and ineffectiveness and regarding the perceived power and potency of others (Cashdan, 1988; Emery & Lesher, 1982). As Hopkins (1986)

198

BORNSTEIN

pointed out, the patient's dependency on the therapist can, if handled correctly, actually facilitate psychotherapy: To the extent that the patient is concerned with pleasing the therapist and strengthening the therapist-patient relationship, the patient will be likely to adhere conscientiously to a variety of therapeutic regimens (see Poldrugo & Forti, 1988, for evidence supporting this assertion). In this context, Ealint (1964, pp. 39-^10) argued that "there are many factors.... which push the patient into a dependent, childish relationship with his doctor. This is inevitable. The only question is. ... how much dependence constitutes a good starting point for psychotherapy, and when does it turn into an obstacle." Goldfarb (1969) further contended that, in general, patient dependency can be used to therapeutic advantage if the therapist does not interfere with a dependent transference early in therapy, but increasingly discourages the patient from exhibiting dependent, help-seeking behaviors as therapy progresses. Because termination involves relinquishing a relationship with an omniscient, omnipotent authority figure, the help-seeking orientation of the dependent patient can make termination difficult; it is not surprising that dependent patients tend to remain in inpatient and outpatient treatment far longer than do nondependent patients. Ironically, the same factors that cause dependent patients to initiate therapy quickly following symptom onset and adhere conscientiously to therapeutic regimens may also make termination more difficult for both patient and therapist (see Bornstein, 1993, for a detailed discussion of this issue). Thus, in many respects the conclusions that emerge from clinical work with dependent patients dovetail with those that stem from the object relations/interactionist model: In both instances, it is clear that dependency can represent either a deficit or a strength, depending upon the circumstances in which it is exhibited and the particular way in which dependent feelings, attitudes, and behaviors are expressed. Like other personality traits that ostensibly seem to represent flaws or deficits (e.g., introversion, narcissism), dependency is neither "all good" nor "all bad." Rather, dependency can be an asset in some situations and a weakness in others. Future reseaxch involving the object relations/interactionist model should examine in detail the strengths and weaknesses associated with high levels of dependency in children, adolescents, and adults. To the extent that clinicians, theoreticians, and researchers become aware of the entire spectrum of dependencyrelated behaviors exhibited by clinical and nonclinical participants, our understanding of the etiology and dynamics of dependency will increase, and our ability to work productively with dependent psychotherapy patients will be enhanced.

REFERENCES

Abraham, K. (1927). The influence of oral erotism on character formation. In C. A. D. Bryan & A. Strachey (Eds.), Selected papers on psychoanalysis (pp. 393^-06). London: Hogarth.

BEYOND ORALITY

199

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1969). Object relations, dependency and attachment: A theoretical review of the infant-mother relationship. Child Development, 40, 969-1025. American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd. ed.. Rev.). Washington, DC: Author. Balint, M. (1964). The doctor, his patient and the illness. London: Pitman Medical. Barnes, C A. (1952). A statistical study of the Freudian theory of levels of psychosexual development. Genetic Psychology Monographs, 15, 105-175. Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monographs, 4(1, PI:. 2), 1-173. Beckwith, J. B. (1986). Eating, drinking and smoking and their relationship in adult women. Psychological Reports, 59, 1089-1095. Beller, E. K. (1957). Dependency and autonomous achievement-striving related to orality and anality in early childhood. Child Development, 29, 287-315. Bertrand, S, & Masting, J. (1969). Oral imagery and alcoholism. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 74, 50-53. Birtchnell, J. (1988). Defining dependence. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 61, 111-123. Black, D. W., Goldstein, R. B., & Mason, E. E. (1992). Prevalence of mental disorder in 88 morbidly obese bariatric clinic patients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 149, 227-234. Blane, H. T., & Chafetz, M. E. (1971). Dependency conflict and sex role identity in drinking delinquents. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 32, 1025-1039. Blatt, S. J. (1974). Levels of object representation in anaclitic and introjective depression. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 29, 107-157. Blatt, S. .1. (1991). A cognitive morphology of psychopathology. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 179, 449-458. Blatt, S. J., Cornell, C. E., & Eshkol, E. (1993). Personality style, differential vulnerability, and clinical course in immunological and cardiovascular disease. Clinical Psychology Review, 13, 421450. Blatt, S. J., & Ford, R. Q. (1994). Therapeutic change. New York: Plenum. Blatt, S. J , & Homann, E. (1992). Parent-child interaction in the etiology of dependent and self-critical depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 12, 47-91. Blatt, S. J., & Shichman, S. (1983). Two primary configurations of psychopathology. Psychoanalysis and Contemporary Thought, 6, 187-254. Blum, G. S., & Miller, D. (1952). Exploring the psychoanalytic theory of the "oral character." Journal of Personality, 20, 287-304. Bornstein, R. F. (1992). The dependent personality: Developmental, social and clinical perspectives. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 3-23. Bornstein, R. F. (1993). The dependent personality. New York: Guilford. Bornstein, R. F. (1994). Adaptive and maladaptive aspects of dependency: An integrative review. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 64, 622-635. Bornstein, R. F. (1995). Active dependency. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 183, 64-77. Bomstein, R. F., & Greenberg, R. P. (1991). Dependency and eating disorders in female psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 179, 148-152. Bomstein, R. F., & Kennedy, T. D. (1994). Interpersonal dependency and academic performance. Journal of Personality Disorders, 8, 240-248. Bornstein, R. F., Manning, K. A., Krukonis, A. B., Rossner, S. C , & Mastrosimone, C. C. (1993). Sex differences in dependency: A comparison of objective and projective measures. Journal of Personality Assessment, 61, 169-181. Bornstein, R. F., Masling, J. M., & Poynton, F. G. (1987). Orality as a factor in interpersonal yielding. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 4, 161-170. Bornstein, R. F., Rossner, S. C , Hill, E. L., & Stepanian, M. (1994). Face validity and fakability of objective and projective measures of dependency. Journal of Personality Assessment, 63, 363-386.

200

BORNSTEIN

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books. Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Sadness and depression. New York: Basic Books. Cashdan, S. (1988). Object relations therapy. New York: Norton. Caspi, A., Bern, D. J., & Eider, G. H. (1989). Continuities and consequences of interactional styles across the life course. Journal of Personality, 57, 375406. Conley, J. J. (1980). Family configuration as an etiological factor in alcoholism. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 89, 670-673. Craig, R. J., Verinis, J. S, & Wexler, S. (1985). Personality characteristics of drug addicts and alcoholics on the MCMI. Jourr.al of Personality Assessment, 49, 156-160. Eagle, M. N. (1984). Recent developments in psychoanalysis. New York: McGraw-Hill. Emery, G., & Lesher, E. (1982). Treatment of depression in older adults: Personality considerations. Psychotherapy, 19, 500-505. Evans, R. G. (1984). MMPI dependency scale norms for alcoholics and psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40, 345-346. Fairbaim, W. R. D. (1952). An object relations theory of the personality. New York1. Basic Books. Fenichel, O. (1945). The psychoanalytic theory of neurosis. New York: Norton. Fisher, S., & Greenberg R. P. (1985). The scientific credibility of Freud's theories and therapy. New York: Columbia University Press. Freud, S. (1905). Three assays on the theory of sexuality. S.E., 7, 125-245. Freud, S. (1908). Character and anal erotism. S.E., 9, 167-176. Freud, S. (1924). The economic problem of masochism. S.E., 19, 155-170. Galatzer-Levy, R. M., St. Cohler, B. J. (1993). The essential other: A developmental psychology of the self. New York: Basic Books. Glover, E. (1925). Notes on oral character formation. International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 6, 131-154. Goldfarb, A. I. (1969). Tne psychodynamics of dependency and the search for aid. In R. A. Kalish(Ed.), The dependencies of old people (pp. 1-15). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Goldman-Eisler, F. (194:!). Breast-feeding and character formation. Journal ofPersonality, 17, 83-103. Goldman-Eisler, F. (1950). The etiology of the oral character in psychoanalytic theory. Journal of Personality, 19, 189-196. Goldman-Eisler, F. (195 I). The problem of "orality" and its origin in early childhood. Journal ofMental Science, 97, 765-78:1. Gottheil, E., & Stone, G. C. (1968). Factor analytic study of orality and anality. Journal ofNervous and Mental Disease, 146 1-17. Greenberg, J. R., & Mitchell, S. J. (1983). Object relations in psychoanalytic theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Greenberg, R. P., & Fisher, S. (1977). The relationship between willingness to adopt the sick role and attitudes toward women. Journal of Chronic Disease, 30, 29-37. Greenspan, S. I. (1989). The development of the ego. New York: International Universities Press. Greenwald, A. G. (1980). The totalitarian ego: Fabrication and revision of personal history. American Psychologist, 35, 603-618. Guntrip, H. (1961). Psychoanalytic theory, therapy and the self. New York: Basic Books. Heinstein, M. 1. (1963). Behavioral correlates of breast-bottle regimes under varying parent-infant relationships. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 28, 1-61. Hopkins, L. B. (1986). Dependency issues and fears in long-term psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 23, 535-539. Horney, K. (1945). Our inner conflicts. New York: Norton. Horowitz, M. J. (1988). introduction to psychodynamics. New York: Basic Books.

BEYOND ORALITY

201

Jacobs, M. A., Anderson, L. S., Champagne, E., Karush, N., Richman, S. J., & Knapp, P. H. (1966). Orality, impuisivity and cigarette smoking in men. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 143, 207-219. Jacobs, M. A., Knapp, P. H., Anderson, L. S., Karush, N., Meissner, R., & Richman, S. J. (1965). Relationship of oral frustration factors with heavy cigarette smoking in males. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 141, 161-171. Jacobs, M. A., & Spilken, A. Z. (1971). Personality patterns associated with heavy cigarette smoking in male college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 37, 428-432. Jacobson, E. (1964). The self and object world. New York: International Universities Press. Jacobson, R., & Robins, C. J. (1989). Social dependency and social support in bulimic and nonbulimic women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 8, 665-670. Jamison, K., & Comrey, A. L. (1968). Further study of dependence as a personality factor. Psychological Reports, 22, 239-242. Jones, E. E., & Pittman, T. S. (1982). Toward a general theory of strategic self-presentation. In J. Suls (Ed.), Psychological perspectives on the self (pp. 231-262). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Jones, M. C. (1968). Personality correlates and antecedents of drinking patterns in adult males. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 32, 2-12. Juni, S. (1981). Maintaining anonymity versus requesting feedback as a function of oral dependency. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 52, 239-242. Juni, S., & Cohen, P. (1985). Partial impulse erogeneity as a function of fixation and object relations. Journal of Sex Research, 21, 275-291. Kammeier, M. L , Hoffman, H., & Loper, R. G. (1973). Personality characteristics of alcoholics as college freshmen and at lime of treatment. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 34, 390-399. Keith, R. R., & Vandenberg, S. G. (1974). Relation between orality and weight. Psychological Reports, 35, 1205-1206. Kernberg, O. (1975). Borderline conditions and pathological narcissism. New York: Aronson. Klein, M. (1945). Contributions to psychoanalysis. London: Hogarth. Kline, P. (1973). The validity of Gottheil's oral trait scale in Great Britain. Journal of Personality Assessment, 37, 551-554. Kline, P., & Storey, R. (1980). The etiology of the oral character. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 136, 85-94. Kohut, H. (1977). The restoration of the self. New York: International Universities Press. Lazare, A., Klerman, G. L., & Armor, D. J. (1966). Oral, obsessive and hysterical personality patterns. Archives of General Psychiatry, 14, 624-630. Lazare, A., Klerman, G. L., & Armor, D. J. (1970). Oral, obsessive and hysterical personality patterns: Replication of factor analysis in an independent sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 7, 275-290. Lenihan, G. O., & Kirk, W. G. (1990). Personality characteristics of eating-disordered outpatients as measured by the Hand Test. Journal of Personality Assessment, 55, 350-361. Levin, A. P., & Hyler, S. E. (1986). DSM-III personality diagnosis in bulimia. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 27, 47-53. Mahler, M. S., Pine, F., & Bergman, A. (1975). The psychological birth of the human infant. New York: Basic Books. Main, M., Kaplan, M., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood and adulthood. Monograplis of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50, 66-104. Masling, J'. M. (1986). Orality, pathology and interpersonal behavior. In J. M. Masling (Ed.), Empirical studies ofpsychoanalytic theories (Vol. 2, pp. 73-106). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

202

BORNSTEIN