Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Carson Gov't Opposition To Motion To Dismiss

Caricato da

Mike KoehlerDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Carson Gov't Opposition To Motion To Dismiss

Caricato da

Mike KoehlerCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 1 of 30 Page ID #:11651

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

ANDR BIROTTE JR. United States Attorney DENNISE D. WILLETT Assistant United States Attorney Chief, Santa Ana Branch Office DOUGLAS F. McCORMICK (180415) Assistant United States Attorney GREGORY W. STAPLES (155505) Assistant United States Attorney 411 West Fourth Street, Suite 8000 Santa Ana, California 92701 Telephone: (714) 338-3541 Facsimile: (714) 338-3564 E-mail: doug.mccormick@usdoj.gov KATHLEEN McGOVERN, Acting Chief CHARLES G. LA BELLA, Deputy Chief (183448) ANDREW GENTIN, Trial Attorney Fraud Section Criminal Division, U.S. Department of Justice 1400 New York Avenue, N.W. Washington, DC 20005 Telephone: (202) 353-3551 Facsimile: (202) 514-0152 E-mail: charles.labella@usdoj.gov andrew.gentin@usdoj.gov Attorneys for Plaintiff United States of America UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA SOUTHERN DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff, v. STUART CARSON et al., Defendants. ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) NO. SA CR 09-00077-JVS GOVERNMENTS OPPOSITION TO DEFENDANTS MOTION TO DISMISS THE INDICTMENT; MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES Hearing Date & Time: May 14, 2012 9:00 a.m.

Plaintiff United States of America, by and through its attorneys of record, the United States Department of Justice, Criminal Division, Fraud Section, and the United States Attorney for the Central District of California (collectively, the

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 2 of 30 Page ID #:11652

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

government), hereby files its Opposition to Defendants Motion to Dismiss the Indictment. This Opposition is based upon the

attached memorandum of points and authorities, the Declaration of Assistant United States Attorney Douglas F. McCormick and exhibits thereto filed concurrently herewith, the files and records in this matter, as well as any evidence or argument presented at any hearing on this matter. DATED: April 6, 2012 Respectfully submitted, ANDRE BIROTTE JR. United States Attorney DENNISE D. WILLETT Assistant United States Attorney Chief, Santa Ana Branch Office DOUGLAS F. McCORMICK Assistant United States Attorney Deputy Chief, Santa Ana Branch Office KATHLEEN McGOVERN, Acting Chief CHARLES G. LA BELLA, Deputy Chief ANDREW GENTIN, Trial Attorney Fraud Section, Criminal Division United States Department of Justice /s/ DOUGLAS F. McCORMICK Assistant United States Attorney Attorneys for Plaintiff United States of America

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 3 of 30 Page ID #:11653

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 IV. D. E. F. G. B. C. DESCRIPTION TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ii

MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES I. II.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 BACKGROUND . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 10

III. ARGUMENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A. The Government Has Gone Beyond Its Discovery Obligations To Ensure That The Defendants Receive Potential Brady Material . . . . . . . . . The Documents CCI Has Been Unable To Locate . . . . Defendants Inability To Access Foreign Third-Party Records . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Denial Of Access To Witnesses . . . . . . . . . . . The FCPA Is Not Void For Vagueness . . . . . . . . . . . . .

10 13 15 15 17 18 19 24

The Travel Act Is Not Void For Vagueness

The Defendants Have Not Been Denied The Right To Present A Complete Defense . . . . . . . .

CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 4 of 30 Page ID #:11654

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 DESCRIPTION CASES:

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES PAGE

Arizona v. Youngblood, 488 U.S. 51 (1988)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

14, 20

California v. Trombetta, 467 U.S. 479 (1984) . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

13, 14, 20 21-22 16, 17 16 14 14

Roviaro v. United States, 353 U.S. 53 (1957) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . United States v. Arboleda, 929 F.2d 858 (1st Cir. 1991) . . . . . . . . . . .

United States v. Black, 767 F.2d 1334 (9th Cir. 1985) . . . . . . . . . . . . . United States v. Booth, 309 F.3d 566 (9th Cir. 2002) United States v. Castro, 887 F.2d 988 (9th Cir. 1989) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

United States v. Cerna, 633 F. Supp. 2d 1053 (N.D. Cal. 2009) . . . . . . . . United States v. Clarke, 767 F. Supp. 2d 12 (D.D.C. 2011)

4, 12 15 20 14 11 20 20 11

. . . . . . . . . . .

United States v. Dring, 930 F.2d 687 (1991) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . United States v. Estrada, 453 F.3d 1208 (9th Cir. 2006) . . . . . . . . . . . . . United States v. Fort, 472 F.3d 1106 (9th Cir. 2007) . . . . . . . . . . . . . United States v. Gastelum- Almeida, 298 F.3d 1167 (9th Cir. 2002) . . . . . . . . . . . . . United States v. Gonzalez, 617 F.2d 1358 (9th Cir. 1980) . . . . . . . . . . . . . United States v. Graham, 484 F.3d 413 (6th Cir. 2007) . . . . . . . . . . . . .

ii

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 5 of 30 Page ID #:11655

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 DESCRIPTION

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (CONTINUED) PAGE 16, 20 12 11 20 20 15

United States v. Hoffman, 832 F.2d 1299 (1st Cir. 1987) . . . . . . . . . . .

United States v. Hsieh Hui Mei Chan, 754 F.2d 817 (9th Cir. 1985) . . . . . . . . . . . . . United States v. Josleyn, 206 F.3d 144 (1st Cir. 2000) . . . . . . . . . . . . .

United States v. Lovasco, 431 U.S. 783 (1977) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . United States v. Medina-Villa, 567 F.3d 507 (9th Cir. 2009) . . . . . . . . . . . . .

United States v. Mejia, 448 F.3d 436 (D.C. Cir. 2006) . . . . . . . . . . . . . United States v. Montgomery, 998 F.2d 1468 (9th Cir. 1993) . . . . . . . . . . .

23, 24 11

United States v. Riley, 657 F.2d 1377 (8th Cir. 1981) . . . . . . . . . . . . . United States v. Sensi, 879 F.2d 888 (D.C. Cir. 1989) . . . . . . . . .

15, 17, 18 3, 4

United States v. Stein, 488 F. Supp. 2d 350 (S.D.N.Y. 2007) . . . . . . . . . United States v. Stever, 603 F.3d 747 (9th Cir. 2010) United States v. Tadros, 310 F.3d 999 (7th Cir. 2002) . . . . . . . . . .

22-23, 24 11

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

United States v. Valenzuela-Bernal, 458 U.S. 858 (1982) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

19, 20 19 17

United States v. Welch, 327 F.3d 1081 (10th Cir. 2003)] . . . . . . . . . . . . United States v. Zabaneh, 837 F.2d 1249 (5th Cir. 1988) . . . . . . . . . . . . . United States v. Zinnel, 2011 WL 6825684 (E.D. Cal.) . . . . . . . . . . . . Workman v. Bell, 178 F.3d 759 (6th Cir. 1998) iii

11, 12 16

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 6 of 30 Page ID #:11656

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES I. INTRODUCTION In their Motion to Dismiss the Indictment (Defts Motion to Dismiss), defendants Stuart Carson, Hong Rose Carson, Paul Cosgrove, and David Edmonds assert that the indictment should be dismissed because the cumulative impediments to present a complete defense have deprived them of their due process and Sixth Amendment rights. Defendants allege that these impediments

include (1) Rule 16 discovery tactics precluding defendants access to millions of pages of normally-discoverable evidence; (2) the lack of a meaningful Brady review; (3) CCIs loss of critical documents underlying many of the counts and transactions; (4) defendants inability to obtain foreign documents and subpoena foreign witnesses; (5) CCI instructing its employees, including key witnesses, not to speak with the defense; and (6) unclear statutes. 8. Defendants motion should be denied. Several of defendants Defts Motion to Dismiss at

claims, including its Rule 16 claims and its arguments regarding the clarity of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) and the Travel Act, have already been addressed and rejected by the Court. Further, the government has gone beyond its discovery

obligations in ensuring that defendants receive Brady/Giglio material in the possession of CCI. Defendants other claims are

meritless and thus defendants motion must fail.

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 7 of 30 Page ID #:11657

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

II. BACKGROUND Because much of defendants motion concerns their claim that they have been denied access to documents in CCIs possession and, as a result, no meaningful Brady review has been conducted, below is a summary of the efforts taken by the government that demonstrate the government has gone beyond its discovery obligations to ensure that the defendants receive potential Brady material. In its December 8, 2009 Order, the Court rejected defendants contention that under Rule 16 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure the governments obligation extends to materials in the possession of a private third party. The Court

based its decision in large part on the language in CCIs plea agreement, in which CCI agreed to disclose to the Department all non-privileged information with respect to the activities of CCI and its affiliates . . . concerning all matters relating to corrupt payments to foreign officials or to employees of private customers . . . and about which the Department . . . shall inquire and provide to the Department, upon request, any nonprivileged document, record or other tangible evidence relating to such corrupt payment. Courts December 8, 2009 Order

(Order) at 2-3 (emphases supplied). In its Order, the Court indicated that [t]he fact that the concept of possession extends to federal agencies participating in the Governments investigation is of no benefit to Carson and made clear that CCI is not a federal agency and is not part of the investigation. Id. at 4-5. 2 The Court found that the

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 8 of 30 Page ID #:11658

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

cooperation terms of the Plea Agreement were not as sweeping and open ended as those in the Deferred Prosecution Agreement in United States v. Stein, 488 F. Supp. 2d 350, 353 (S.D.N.Y. 2007), which required the disclosure of all information in the companys possession. As the Court stated, [b]y no stretch of

the imagination did CCI enter into an agreement allowing the Government to request anything in the possession of CCI. at 5. Order

The CCI Plea Agreement only called for the production of

information related to corrupt payments. On June 4, 2010, defendants wrote in a letter that the government should ask Steptoe & Johnson LLP (Steptoe), to make available the 75-million-page electronic database that CCI created during its internal investigation so that a proper Brady review may be conducted. See Exhibit A at 2.1 At a minimum,

defendants stated, the government should request ten categories of material from Steptoe that the defendants believed may contain Brady material. Id. at 2-4.

In a June 30, 2010 letter, the government responded that it remained committed to meeting its Brady obligations, that the Court had previously ruled that under Rule 16 the governments obligation does not extend to material in the possession of a private third party, and that the government could not find any authority that extended the governments Brady obligations to information in the possession of a private third-party. The

government invited defendants to share any authority that might

All citations to Exhibits A through S are citations to the exhibits attached to the Declaration of Assistant United States Attorney Douglas F. McCormick filed concurrently herewith. 3

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 9 of 30 Page ID #:11659

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

provide otherwise.

See Exhibit B at 1-2.

On August 11, 2010, the defendants provided a draft motion they intended to file in order to compel the government to comply with its Brady/Giglio requirements. See Exhibit C. Defendants

wrote in an accompanying letter that the motion relies on numerous authorities specifying the circumstances under which a prosecutors Brady/Giglio obligations extend to materials in the possession of third parties. Id. at 1.

On September 10, 2010, the government reiterated that it does not have a generalized obligation to conduct a Brady review of materials in the possession of a third-party. The government

stated, however, that it would be contrary to the spirit of Brady and its progeny for the government willfully to ignore the potential existence of exculpatory evidence simply because it is not in our possession. See Exhibit D at 1. To that end, the

government invited defendants to follow the procedures identified by the district court in United States v. Cerna, 633 F.Supp.2d 1053, 1061 (N.D. Cal. 2009), where the court outlined that a defendant may put the government on notice of potential exculpatory evidence through a narrowly defined and well directed request . . . explaining why exculpatory material might be found in a certain file. Exhibit D at 2. The government

indicated in its letter that many of the broad categories of information sought in defendants June 4, 2010 letter and in the draft motion would not meet the Cerna standard and invited the defendants to supplement their Brady requests. On November 5, 2010, defendants indicated that they did not agree that the Cerna procedure satisfies the governments Brady 4

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 10 of 30 Page ID #:11660

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

obligation to conduct its own review to identify exculpatory information. See Exhibit E at 1. Defendants proceeded to

provide a list of 77 categories of documents which they requested the government obtain from CCI. Id. at 2-10.

On November 17, 2010, the government and defendants held a meet and confer at which time the parties discussed the 77 categories of documents requested by defendants. The government

stated that, although it did not believe it was required to do so, it would request certain of the categories of documents from CCI. On November 29, 2010, the government orally requested that CCI produce to the government the interview memoranda prepared by Steptoe summarizing the witness interviews for which Steptoe previously provided complete or partial oral summaries to the government.2 The government also requested that Steptoe provide

additional oral summaries of the witness interviews conducted by Steptoe that were not previously summarized for the government. On November 30, 2010, the government requested that CCI make production of all transaction-related documents for the charged payments and the thirty additional transactions previously identified by the government. See Exhibit F at 1-2. The request

included, but was not limited to, the following documents for each of the relevant transactions: the project file, project management file, order package, bid documents, technical specifications, purchase order, any email communications regarding specifications or commissions, Customer Order Review The government subsequently sent letters to the defendants describing the statements given by the witnesses to Steptoe. 5

2

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 11 of 30 Page ID #:11661

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

Board (CORB) documents, third-party agreement and approval forms, and payment records. Id. at 1. The government also

requested (1) the production of any forensic image taken of any laptop computer, desktop computer, PDA, or cellular telephone used by the defendants and (2) any correspondence between CCI and its affiliates or anyone acting on CCIs behalf and any thirdparty representative in which such representative denied or rejected allegations of any improper or corrupt payment. 2. On December 9, 2010, CCI declined the governments request that it produce to the government the interview memoranda prepared by Steptoe summarizing the witness interviews for which Steptoe previously provided complete or partial oral summaries to the government. See Exhibit G. CCI indicated that the Id. at

government was not legally entitled to hard copies of the interview memoranda at issue based on the express terms of the Non-Waiver Agreement and the Plea Agreement. Id. at 3.

On December 14, 2010, CCI declined the governments request that it provide any additional oral summaries of the witness interviews conducted by Steptoe that were not previously summarized for the government. See Exhibit H. CCI indicated

that any open invitation to the government to receive such summaries as part of CCIs cooperation expired no later than the time the Plea Agreement was entered. Id.

On December 15, 2010, the government wrote a letter to the defendants stating that it had requested that CCI produce the materials specified in its November 30, 2010 letter. I. See Exhibit

The government also informed the defendants that Steptoe had 6

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 12 of 30 Page ID #:11662

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

declined the governments oral request to produce the interview memoranda and additional oral summaries. Id. at 2.

On January 14, 2011, counsel for Hong Rose Carson wrote a letter to the government requesting that the government ask CCI to produce an additional eight categories of material that counsel believed constituted exculpatory evidence. J. On January 21, 2011, in response to the governments November 30, 2010 letter, Steptoe produced to the government (1) a hard drive consisting of 424,497 documents of transactionrelated documents; (2) the hard drives and other devices of defendants Hong Rose Carson, Paul Cosgrove, David Edmonds, and Flavio Ricotti (CCI did not possess forensic images of any of Stuart Carsons computers or devices); and (3) a compact disc containing over 15,000 pages of project file documents. Exhibit K. See See Exhibit

With respect to the third category, Steptoe indicated

that it was unable to locate project file documents for several of the transactions. Id. at 3. The government produced the

above-referenced materials to the defendants on January 27, 2011, together with Steptoes explanatory letter. On March 18, 2011, in further response to the governments November 30, 2010 letter, Steptoe produced to the government over 5,000 pages of additional project file documents, commission payment records, and agent correspondence. See Exhibit L.

Steptoe indicated that it had been unable to locate commission payment records for approximately seventeen of the thirty additional transactions. (Steptoe had previously produced

commission payment records for all of the charged transactions.) 7

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 13 of 30 Page ID #:11663

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

The government produced the above-referenced materials to the defendants on March 23, 2011, together with Steptoes explanatory letter. On March 23, 2011, the government explained to the defense its responses to each of the nearly 100 Brady requests made in defendants November 5, 2010 letter and Ms. Carsons January 14, 2011 letter, and indicated it would be requesting that CCI produce several additional categories of documents. M. On March 29, 2011, the government requested from Steptoe the production of twenty-eight categories of documents, which were largely derived from defendants prior Brady requests. Exhibit N. See See Exhibit

The government also requested that Steptoe identify

any evidence that caused it to have doubt as to whether any of the transactions at issue were consummated or were improper. at 5. On April 5, 2011, in further response to the governments November 30, 2010 letter, Steptoe produced to the government over 17,000 pages of documents of additional project files and agent correspondence. See Exhibit O. Steptoe indicated it had been Id.

unable to locate project files for seven of the charged transactions and thirteen of the thirty additional transactions. Id. at 2. The government produced the above-referenced materials

to the defendants on April 7, 2011, together with Steptoes explanatory letter. On April 14, 2011, Steptoe responded to the governments March 29, 2011 letter containing the additional 28 document requests. See Exhibit P. Steptoe explained that it would not be 8

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 14 of 30 Page ID #:11664

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

able to produce responsive documents for several of the requested categories on the grounds that the requests (1) fell outside of the scope of the plea agreement cooperation clause; (2) called for privileged materials; (3) called for documents in the possession of IMI; or (4) were otherwise vague. Id. at 2-4.

Steptoe indicated that CCI would be willing to comply with any revised requests that did not fall into these categories. 4. On May 5, 2011, the government informed the defendants of Steptoes refusal to waive the attorney-client privilege and attorney work-product doctrine with respect to certain material and invited the defendants to seek an order from the Court to the extent defendants believed Steptoes invocation of the privilege was improper. See Exhibit Q. Similarly, the government invited Id. at

the defendants to seek an order from the Court to the extent they believed that the limitation regarding the documents in IMIs possession was improper. Id. at 2.

On May 13 and 17, 2011, the government engaged in additional discussions with Steptoe concerning the requests for categories of documents that Steptoe originally indicated it would not produce, and Steptoe agreed to comply with several of these requests. On June 10 and August 18, 2011, in response to the governments March 29, 2011 letter with the twenty-eight additional categories, Steptoe produced a total of over 2,300 pages of documents to the government. See Exhibits R & S.

Steptoe also provided explanations for what was and was not produced for almost all of the categories in its accompanying 9

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 15 of 30 Page ID #:11665

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

letters.

Id.

The government subsequently produced the above-

referenced materials to the defendants together with Steptoes explanatory letters. III. ARGUMENT The Court should deny Defendants Motion to Dismiss. Defendants have failed to show how any one of the impediments they allege have deprived them of their due process and Sixth Amendment rights. The government has gone beyond its discovery

obligations in ensuring that defendants receive potential Brady material in the possession of CCI. The Court has already ruled

that the FCPA and the Travel Act are not void for vagueness. With regard to their access to evidence claims, the defendants have failed to show that the government has engaged in bad faith or that any act or omission alleged can be attributed to the government. Further, the defendant have not demonstrated that

any of the missing evidence would have been material and favorable to the defense. A. The Government Has Gone Beyond Its Discovery Obligations To Ensure That The Defendants Receive Potential Brady Material Defendants assert that their Brady rights have been eviscerated as a result of their inability to obtain alleged Brady material in the possession of CCI. baseless. This assertion is

While there is no authority that extends the

governments Brady obligations to information in the possession of a private third-party, as demonstrated above the government has nonetheless made every effort to ensure that the defendants receive potential Brady material in the possession of 10

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 16 of 30 Page ID #:11666

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

CCI/Steptoe. Relying in part on United States v. Fort, 472 F.3d 1106, 1118 (9th Cir. 2007), the Court has previously held that the governments Rule 16 obligations do not extend to materials in the possession of CCI. Other courts have similarly held that the

governments Brady obligations do not extend to information in the possession of a private third-party, even where such a thirdparty is cooperating with the governments investigation. United States v. Graham, 484 F.3d 413, 417 (6th Cir. 2007) (Brady clearly does not impose an affirmative duty upon the government to take action to discover information which it does not possess); United States v. Tadros, 310 F.3d 999, 1005 (7th Cir. 2002) (government does not have duty to gather potential Brady material from third party and tender it to the defendant); United States v. Josleyn, 206 F.3d 144, 152-54 (1st Cir. 2000) (While prosecutors may be held accountable for information known to police investigators, we are loath to extend the analogy from police investigators to cooperating private parties who have their own set of interests); see also United States v. Riley, 657 F.2d 1377, 1386 (8th Cir. 1981) (While Brady requires the Government to tender to the defense all exculpatory evidence in its possession, it establishes no obligation on the Government to seek out such evidence.). A district court in this circuit recently affirmed this principle. In United States v. Zinnel, 2011 WL 6825684 (E.D. See

Cal.) (slip copy), the court overruled a prior decision of a magistrate judge holding that the government should produce Brady and Giglio materials in the possession of a private trustee in a 11

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 17 of 30 Page ID #:11667

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

bankruptcy fraud prosecution.

The court found that the

government should produce information for purposes of Rule 16 and Brady/Giglio only to the extent that information is deemed accessible to the prosecution. Access is deemed present only

with respect to materials actually in the possession of the federal government. Id. at *1. The court found that physical

possession was the dispositive factor and that the government has no duty to produce information beyond what it actually has. Id.; see also United States v. Hsieh Hui Mei Chan, 754 F.2d 817, 824 (9th Cir. 1985) (government has no duty to volunteer information that it does not possess or of which it is unaware). Despite this clear precedent, the government invited the defendants to follow the procedures identified by the district court in United States v. Cerna, where the court outlined how a defendant may put the government on notice of potential exculpatory evidence: Where a prosecutor has a specific reason to suspect that Brady material may reside at a source, of course, the prosecutor must inquire. . . . A related factor can be a narrowly defined and well directed request by defense counsel explaining why exculpatory material might be found in a certain file. . . . [A] well-framed and well-timed letter may heighten the diligence due from a prosecutor by informing him or her of circumstances the prosecutor could not reasonably be expected to know. 633 F. Supp. 2d at 1061. After several rounds of discussion with the defendants, in accordance with Cerna, the government requested materials from CCI in November 2010 and March 2011. As indicated above, as a

result of these requests, CCI produced (1) all transactionrelated documents for the charged payments and the thirty

12

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 18 of 30 Page ID #:11668

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

additional transactions in CCIs possession, including the project files; (2) forensic images of the defendants computers and other devices; (3) correspondence with third-party representatives in which the representative denied or rejected allegations of any improper or corrupt payments; and (4) over 2,300 pages of documents responsive to the governments March 29, 2011 letter containing twenty-eight additional categories of materials. The government, in turn, produced this material to

the defendants. Despite this painstaking approach taken by the government to ensure that defendants receive potential Brady material, defendants nonetheless claim that their Brady rights have been eviscerated. Defts Motion to Dismiss at 28. Contrary to

defendants assertion, the facts set forth above together with the attached correspondence demonstrate that the government has gone above and beyond its obligations to ensure that it has complied with both the law and the spirit of Brady and its progeny. B. The Documents CCI Has Been Unable To Locate Defendants assert that they have been prejudiced because CCI has been unable to locate (1) the project files for the transactions underlying seven of the charged counts and (2) the project files and commission payment records for several of the additional thirty transactions. The government does not possess

these records either, and there is no allegation that the government has lost any material. In California v. Trombetta, 467 U.S. 479, 489 (1984), the Supreme Court held that for destruction or loss of evidence to 13

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 19 of 30 Page ID #:11669

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

constitute a constitutional violation, the evidence must both possess an exculpatory value that was apparent before the evidence was destroyed, and be of such a nature that the defendant would be unable to obtain comparable evidence by other reasonably available means. In Arizona v. Youngblood, 488 U.S.

51, 58 (1988), the Court further held that where lost or destroyed evidence is deemed to be only potentially exculpatory, as opposed to apparently exculpatory, the defendant must show that the evidence was destroyed in bad faith. The governments

duty to preserve material evidence is limited to evidence it has gathered. Trombetta, 467 U.S. at 488-90. There cannot

Here, defendants cannot meet these standards.

be any governmental bad faith because there is no showing that the government played any role in CCIs failure to maintain the records. See, e.g., United States v. Estrada, 453 F.3d 1208,

1213 (9th Cir. 2006) (no due process violation where no showing that government knew or intended for evidentiary material to be sold by third party); United States v. Booth, 309 F.3d 566, 574 (9th Cir. 2002) (no bad faith failure to preserve evidence where government did not take possession of computer hard drives but only informed third party vendors - who later erased the drives that it did not need copies of the information on the hard drives and where there was nothing about the hard drives that would have made their allegedly exculpatory nature apparent to the government); United States v. Castro, 887 F.2d 988, 999 (9th Cir. 1989) (defendant may not claim violation of due process rights regarding missing evidence in absence of action by government). Further, there is no basis to believe that the unavailable 14

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 20 of 30 Page ID #:11670

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

material has any exculpatory value. C. Defendants Inability To Access Foreign Third-Party Records Defendants assert that due to issues of sovereignty, they have been unable to access documents in the possession of foreign entities. Specifically, they claim they have been unable to

obtain bank records from Malaysia because of banking/privacy laws and that China has denied their letter rogatory. Defendants

compare their lack of ability to obtain foreign records with that of the government, who can use various mutual legal assistance treaties to obtain evidence from overseas. Similar claims have been made in other criminal prosecutions and courts have uniformly rejected them. For example, in United

States v. Clarke, 767 F. Supp. 2d 12, 70-72 (D.D.C. 2011), a defendant asserted that he was denied due process of law where Trinidad failed to provide any documents in response to his letter rogatory seeking documents. The court stated that the

right to compulsory process only extends to those areas within the territorial power of the United States courts and that a defendants inability to obtain foreign documents is not a bar to criminal prosecution. Id. at 71 (citing United States v. Sensi,

879 F.2d 888, 889 (D.C. Cir. 1989)); see also United States v. Mejia, 448 F.3d 436, 444-45 (D.C. Cir. 2006) (defendants inability to obtain tapes and transcripts from Costa Rica did not give rise to a violation of their Sixth Amendment rights). D. Denial Of Access To Witnesses Citing a December 2008 e-mail from the then-general counsel of CCI to CCI employees, defendants assert that the government has benefitted from steps CCI has taken to inhibit defendants 15

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 21 of 30 Page ID #:11671

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

ability to interview witnesses.

Specifically, defendants claim

that sixteen months after the governments investigation began but before the case was indicted CCI employees were influenced by CCIs then-general counsel not to talk to defense investigators and, thus, CCI actively prevented defendants from speaking to individuals potentially with exculpatory information. The

defendants also claim that many of the percipient witnesses are in foreign jurisdictions and not subject to any compulsory process. Both sides have the right to interview witnesses before trial. 1985). United States v. Black, 767 F.2d 1334, 1337 (9th Cir. Although unjustifiable government interference with a

defendants right of access to a witness is improper, no right of a defendant is violated when a potential witness freely chooses not to talk. 868 (1st Cir. 1991). United States v. Arboleda, 929 F.2d 858, Unless a witness refusal to speak to the

defense was caused by action on the part of an agent of the prosecution, there is no denial of access by the government. Id.; see also United States v. Hoffman, 832 F.2d 1299, 1303-04 (1st Cir. 1987) (finding of interference with Sixth Amendment rights requires causal connection between government action and defendants inability to obtain witness). Here, the government did not direct or have knowledge of the admonition given to CCI employees by its then-general counsel. As a result, there is no causal connection between government action and the defendants ability to interview witnesses. See

Workman v. Bell, 178 F.3d 759, 771 (6th Cir. 1998) (no denial of due process where witnesss boss told her not to give any 16

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 22 of 30 Page ID #:11672

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

statements to defense lawyers where there was no evidence the prosecution contacted the witnesss boss); Arboleda, 929 F.2d at 868 (defendant failed to establish the necessary causal link between the governments conduct and any denial of access to the witness). Defendants claim that they have been denied constitutional rights as a result of being unable to subpoena foreign witnesses must also fail. It is well-settled that a defendants inability

to subpoena foreign witnesses is not a bar to criminal prosecution. United States v. Sensi, 879 F.2d at 899; see also

United States v. Zabaneh, 837 F.2d 1249, 1259-60 (5th Cir. 1988) (It is well established . . . that convictions are not unconstitutional under the Sixth Amendment even though the United States courts lack power to subpoena witnesses (other than American citizens) from foreign countries.). Moreover, as in

Sensi, defendants did not use all the means at their disposal, such as seeking court permission to depose non-voluntary witnesses residing overseas, to obtain the needed testimony. United States v. Sensi, 879 F.2d at 899. E. The FCPA Is Not Void For Vagueness Defendants assert that portions of the FCPA are obscurely written and a key term at issue in this case - instrumentality - is not defined in the statute. They claim that the Lay See

Persons Guide to the FCPA Statute was not published until 1994, that there has been insufficient public education about the Act, and that the FCPA Opinion Procedure has only yielded 33 opinions about whether prospective conduct would conform to DOJs enforcement policies. 17

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 23 of 30 Page ID #:11673

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

Defendants claims are simply a rehashing of the void-forvagueness arguments they previously made in their Motion to Dismiss Counts One Through Ten of the Indictment. at 51-59.3 See Dkt. #317

In its Order Denying Defendants Motion, the Court

found that the statutory language of the FCPA is clear, that the statutory scheme is coherent and consistent, and that resort to the legislative history of the FCPA is unnecessary. #373 at 11-12. See Dkt.

The Court further found that [a]fter considering

the text, structure, history, and purpose of the FCPA, the Court finds that there is no grievous ambiguity or uncertainty in the statute such that the Court must simply guess as to what Congress intended and that the ordinary meaning of instrumentality indicates that state-owned companies could fall under the ambit of the FCPA. omitted). F. The Travel Act Is Not Void For Vagueness Defendants claim that prosecution under the Travel Act raises similar issues to those arising under the FCPA and that the Department has improperly broadened the application of the statute to apply it to foreign commercial bribery. These claims are a rehashing of the void-for-vagueness arguments that were made by defendants in their Motion to Dismiss Counts One, Eleven, Twelve and Fourteen of the Indictment. Dkt. #376 at 30-31. See Id. at 14 (internal citation

In its Order Denying Defendants Motion, the

Defendants admit as much and indicate they are reiterating the issues only to reinforce the overall fundamental unfairness in DOJs recent and overly broad interpretations of these statutes. Defts Motion to Dismiss at 19, n.22. 18

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 24 of 30 Page ID #:11674

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

Court found that the text of both the Travel Act and Californias Commercial Bribery Statute were clear and provided adequate notice to defendants that they could be applied to a commercial bribe consummated outside of California. See Dkt. #440 at 13.

Further, the Court held that cases such as [United States v. Welch, 327 F.3d 1081 (10th Cir. 2003)] demonstrate that the Travel Act is not being dusted off and employed arbitrarily. Id. G. The Defendants Have Not Been Denied The Right To Present A Complete Defense Defendants assert that the cumulative impact of impediments to present a complete defense warrant dismissal as a due process violation. Defts Motion to Dismiss at 19. They argue that the

Supreme Court has held that fundamental fairness requires the right to present a defense, including access to evidence, in a variety of settings. Id. at 20. Specifically, they claim that

their constitutional rights to develop and present a complete defense has been infringed due to lack of access to documents and witnesses and the governments failure to conduct a meaningful Brady review. Id. at 23.

In United States v. Valenzuela-Bernal, 458 U.S. 858, 866-67 (1982), the Supreme Court rejected the conceivable benefit test previously used by the Ninth Circuit in favor of a test that required the defendant to show how the missing testimony was both material and favorable to his defense. The Ninth Circuit has

indicated that in the case of a missing witness the defendant must make an initial showing that the Government acted in bad faith and that this conduct resulted in prejudice to the

19

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 25 of 30 Page ID #:11675

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

defendants case.

United States v. Dring, 930 F.2d 687, 693

(1991) (emphasis in original); United States v. Medina-Villa, 567 F.3d 507, 517 (9th Cir. 2009) (same); United States v. GastelumAlmeida, 298 F.3d 1167, 1174 (9th Cir. 2002) (same). Due process

is not violated unless a material witnesss unavailability is attributable to unilateral government action. Gonzalez, 617 F.2d 1358, 1363 (9th Cir. 1980). United States v. There can be no

violation of the defenses right to present evidence unless some contested act or omission can be attributed to the sovereign. Hoffman, 832 F.2d at 1303. To prevail under the prejudice prong,

the defendant must at least make a plausible showing that the testimony of the deported witnesses would have been material and favorable to his defense, in ways not merely cumulative to the testimony of available witnesses. at 873. Similarly, in cases of lost or missing evidence, the Supreme Court has made clear that the defendant must make a showing of bad faith by the government and prejudice. See Arizona v. Valenzuela-Bernal, 458 U.S.

Youngblood, 488 U.S. at 55-57; California v. Trombetta, 467 U.S. at 488-89; United States v. Lovasco, 431 U.S. 783, 789-90 (1977). Defendants cannot show that any of the missing evidence is due to an act or omission on the part of the government or to the governments bad faith. They also fail to show that the missing

evidence or witnesses are favorable and material to their case. The cases they cite in support of their claim all involve direct governmental conduct where the missing evidence was material and favorable to the defendants, circumstances which are not present here. 20

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 26 of 30 Page ID #:11676

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

Defendants cite to Roviaro v. United States, 353 U.S. 53 (1957), where the government withheld the identity of an informer-eyewitness from the defense. The Supreme Court found

that, on the facts present, the defendants had made the required showing of materiality with regard to a missing witness who was central to the case: This is a case where the Governments informer was the sole participant, other than the accused in the transaction charged. The informer was the only witness in a position to amplify or contradict the testimony of government witnesses. Moreover, a government witness testified that [the informer] denied knowing petitioner or ever having seen him before. We conclude that, under these circumstances, the trial court committed prejudicial error in permitting the Government to withhold the identity of its undercover employee in the face of repeated demands by the accused for his disclosure. Id. at 64-65 (emphases supplied). Defendants attempt to compare

these stark facts with those in their own case, arguing that the missing project files and commission payment records define the very transactions the government seeks to claim were not bona fide. Defts Motion to Dismiss at 24. Defendants also argue

that, unlike the defendant in Roviaro, they were not present at the alleged crime. Id. at 25.

The facts of Roviaro are a far cry from those in this case. In Roviaro, the informer was the sole participant, other than the accused, in the transaction and had denied knowing the defendant or having seen him before. As a result, the Court found that the In

defendant had made the requisite materiality showing.

defendants case, the missing records are a small subset of the millions of pages of produced documents. The defendants possess

the key documents - the e-mails and relevant commission payment

21

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 27 of 30 Page ID #:11677

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

records - for each charged transaction.4

The hard copy project

files, while providing further background on the projects themselves and their commercial terms, are not central to the issue of whether the defendants violated the FCPA or Travel Act. Unlike the missing witness in Roviaro, there is no indication that any missing records would be material and favorable to the defendants or any basis to believe the governments actions led to the records not being maintained. Defendants reliance on United States v. Stever, 603 F.3d 747 (9th Cir. 2010), is also misplaced. In Stever, the

government indicated it possessed reports concerning Mexican drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) operating in the vicinity of the marijuana plants on defendants property but refused to produce the reports. The trial court upheld the governments

refusal and also ruled that it would not permit the defendant to put on evidence regarding Mexican DTOs or who else might have been involved in growing the plants. In reversing the

conviction, the appeals court held that because of these rulings the defendant could not make his defense in any form as the court excluded the sole evidence of an issue that constituted a major part of the attempted defense. . . . [The defendant] was, quite literally, prevented from making his defense. . . . Having denied [the defendant] the opportunity to explore this discovery avenue, the district court declared a range of defense theories

Because the government does not intend to prove that the additional thirty transactions are themselves violations of the FCPA or Travel Act, the missing records with respect to these transactions are even less relevant. 22

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 28 of 30 Page ID #:11678

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

off-limits, without considering in any detail the available evidence it was excluding. Id. at 757 (emphasis in original).

Thus, Stever primarily involved an erroneous evidentiary ruling. The appeals court made clear that when evidence is

excluded on the basis of an improper application of the evidentiary rules, due process concerns are still greater because the exclusion is unsupported by any legitimate state justification. Id. at 755. The evidence unavailable to the

defendant constituted the sole evidence related to his defense and prevented the defendant from making his defense at all. indicated above, these facts do not at all equate with the missing evidence in the Carson case. Further, the missing As

evidence the defendants allude to has never been in the possession of the government. Similarly, defendants reliance on United States v. Montgomery, 998 F.2d 1468 (9th Cir. 1993), is inapposite. In

Montgomery, the court found that the government failed to use reasonable efforts to produce a confidential informant. According to the court, the government did absolutely nothing to (1) locate the informant, (2) ensure that it would be able to locate the informant when necessary, or (3) notify the informant that he must be available for an interview by a certain date. Id. at 1474. As a result, the informant fled and was unavailable The court found that the informants

to the defendants.

testimony was material and favorable to the defendants case. Specifically, the court found that: [The informants] testimony was crucial to [the defendants] entrapment defense. [The informant] was at the center of the alleged conspiracy and instrumental 23

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 29 of 30 Page ID #:11679

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

to the drug transactions. [The informant] provided all the information which the DEA possessed concerning [the defendant] and the alleged conspiracy. In addition, [the informant] was in contact with [the defendant] pursuant to DEA instructions, with the intent of soliciting a sale of drugs. Id. at 1478. As in Roviaro, the informant was the central figure Further, the court, while

in the drug transactions at issue.

making reference to matters about which the informant might testify, had the benefit of the informants actual testimony at his own sentencing hearing and his subsequent testimony at defendants hearing pursuant to 18 U.S.C. 2255 and thus had a basis to believe that the informants testimony would be material and favorable. Id. at 1472.

As is the case with Roviaro and Stever, the facts of Montgomery are not analogous to those present here. The missing

witnesses or evidence in these three cases all constituted the key piece of evidence for the defendants. In all three cases,

the courts found that (1) the act or omission was caused by the government and that (2) the missing evidence was material and favorable. prongs. IV. CONCLUSION The Court has already denied defendants void-for-vagueness arguments concerning the FCPA and the Travel Act. The government Defendants cannot succeed on either of these two

has gone beyond its obligations to ensure that defendants receive possible Brady material in the possession of CCI. Defendants

lack of access to evidence claims must fail because the government had no role in causing the missing evidence and the

24

Case 8:09-cr-00077-JVS Document 660

Filed 04/06/12 Page 30 of 30 Page ID #:11680

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

defendants cannot demonstrate that such evidence is material and favorable to the defense. Dismiss should be denied. Accordingly, Defendants Motion to

25

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- U.S. v. Lambert (DOJ Response)Documento63 pagineU.S. v. Lambert (DOJ Response)Mike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- U.S. v. Lambert (Lambert Appeal)Documento40 pagineU.S. v. Lambert (Lambert Appeal)Mike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- U.S. v. Antonio Pere YcazaDocumento21 pagineU.S. v. Antonio Pere YcazaMike Koehler100% (1)

- Amendments To The FCPA's Anti-Bribery Provisions Capable of Capturing The "Demand Side" of Bribery.Documento13 pagineAmendments To The FCPA's Anti-Bribery Provisions Capable of Capturing The "Demand Side" of Bribery.Mike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- SEC v. CoburnDocumento17 pagineSEC v. CoburnMike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- U.S. v. Enrique Pere YcazaDocumento18 pagineU.S. v. Enrique Pere YcazaMike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- NG Jury InstructionsDocumento72 pagineNG Jury InstructionsMike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- Proposed FCPA AmendmentsDocumento13 pagineProposed FCPA AmendmentsMike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- NG Internal Controls CaseDocumento18 pagineNG Internal Controls CaseMike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- SMI Plea AgreementDocumento63 pagineSMI Plea AgreementMike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

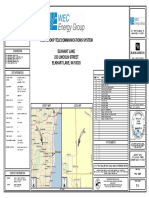

- Wec Group Telecommunications System Elkhart Lake 220 Lincoln Street Elkhart Lake, Wi 53020Documento18 pagineWec Group Telecommunications System Elkhart Lake 220 Lincoln Street Elkhart Lake, Wi 53020Mike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- Teva Whistleblower (SEC Response)Documento38 pagineTeva Whistleblower (SEC Response)Mike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- Bahn SentencingDocumento58 pagineBahn SentencingMike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- U.S. v. Lambert (Motion To Compel)Documento24 pagineU.S. v. Lambert (Motion To Compel)Mike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- SEC v. Coburn (Coburn Opposition)Documento19 pagineSEC v. Coburn (Coburn Opposition)Mike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- SETA ComplaintDocumento39 pagineSETA ComplaintMike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- Teva Whistleblower Writ of MandamusDocumento47 pagineTeva Whistleblower Writ of MandamusMike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- Swedish Court Decision Re Telia ExecsDocumento99 pagineSwedish Court Decision Re Telia ExecsMike Koehler100% (2)

- U.S. V Ho Motion To DismissDocumento27 pagineU.S. V Ho Motion To DismissMike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- Lyons Bribery ChargesDocumento13 pagineLyons Bribery ChargesHNN100% (10)

- U.S. v. Bahn (Sentencing)Documento28 pagineU.S. v. Bahn (Sentencing)Mike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- FCPA Professor Depot DispatchDocumento1 paginaFCPA Professor Depot DispatchMike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- Chatburn IndictmentDocumento15 pagineChatburn IndictmentMike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- SETA ComplaintDocumento39 pagineSETA ComplaintMike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- U.S. v. Ho (DOJ Response Brief)Documento31 pagineU.S. v. Ho (DOJ Response Brief)Mike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- Parker InformationDocumento10 pagineParker InformationMike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- U.S. v. Transport Logistics Int'l (Order)Documento3 pagineU.S. v. Transport Logistics Int'l (Order)Mike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- Wang InformationDocumento10 pagineWang InformationMike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- Parker ProfferDocumento4 pagineParker ProfferMike KoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- Africo Resources Ltd. LetterDocumento26 pagineAfrico Resources Ltd. LetterMike Koehler100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Adventures in PioneeringDocumento202 pagineAdventures in PioneeringShawn GuttmanNessuna valutazione finora

- New Microwave Lab ManualDocumento35 pagineNew Microwave Lab ManualRadhikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cat IQ TestDocumento3 pagineCat IQ TestBrendan Bowen100% (1)

- Defender 90 110 Workshop Manual 5 WiringDocumento112 pagineDefender 90 110 Workshop Manual 5 WiringChris Woodhouse50% (2)

- 2021.01.28 - Price Variation of Steel Items - SAIL Ex-Works Prices of Steel - RB-CivilDocumento2 pagine2021.01.28 - Price Variation of Steel Items - SAIL Ex-Works Prices of Steel - RB-CivilSaugata HalderNessuna valutazione finora

- PrognosisDocumento7 paginePrognosisprabadayoeNessuna valutazione finora

- Linear Piston Actuators: by Sekhar Samy, CCI, and Dave Stemler, CCIDocumento18 pagineLinear Piston Actuators: by Sekhar Samy, CCI, and Dave Stemler, CCIapi-3854910Nessuna valutazione finora

- Clinnic Panel Penag 2014Documento8 pagineClinnic Panel Penag 2014Cikgu Mohd NoorNessuna valutazione finora

- Mega Goal 4Documento52 pagineMega Goal 4mahgoubkamel0% (1)

- Human Resource Management (MGT 4320) : Kulliyyah of Economics and Management SciencesDocumento9 pagineHuman Resource Management (MGT 4320) : Kulliyyah of Economics and Management SciencesAbuzafar AbdullahNessuna valutazione finora

- Compabloc Manual NewestDocumento36 pagineCompabloc Manual NewestAnonymous nw5AXJqjdNessuna valutazione finora

- 360 PathwaysDocumento4 pagine360 PathwaysAlberto StrusbergNessuna valutazione finora

- PMMC ExperimentDocumento2 paginePMMC ExperimentShyam ShankarNessuna valutazione finora

- Anti-Anginal DrugsDocumento39 pagineAnti-Anginal Drugspoonam rana100% (1)

- Appraisal Sample PDFDocumento22 pagineAppraisal Sample PDFkiruthikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Vernacular Architecture: Bhunga Houses, GujaratDocumento12 pagineVernacular Architecture: Bhunga Houses, GujaratArjun GuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- SBFP Timeline 2019Documento1 paginaSBFP Timeline 2019Marlon Berjolano Ere-erNessuna valutazione finora

- Argenti, P. Corporate Communication. Cap. 8-9Documento28 pagineArgenti, P. Corporate Communication. Cap. 8-9juan100% (1)

- Nanofil Manual PDFDocumento5 pagineNanofil Manual PDFJuliana FreimanNessuna valutazione finora

- Benedict - Ethnic Stereotypes and Colonized Peoples at World's Fairs - Fair RepresentationsDocumento16 pagineBenedict - Ethnic Stereotypes and Colonized Peoples at World's Fairs - Fair RepresentationsVeronica UribeNessuna valutazione finora

- Philosophy of Disciple Making PaperDocumento5 paginePhilosophy of Disciple Making Paperapi-665038631Nessuna valutazione finora

- Money MBA 1Documento4 pagineMoney MBA 1neaman_ahmed0% (1)

- IJRP 2018 Issue 8 Final REVISED 2 PDFDocumento25 pagineIJRP 2018 Issue 8 Final REVISED 2 PDFCarlos VegaNessuna valutazione finora

- OB HandoutsDocumento16 pagineOB HandoutsericNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Analysis of CriminologyDocumento12 pagineCase Analysis of CriminologyinderpreetNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessing Khazaria-Serpent PeopleDocumento1 paginaAssessing Khazaria-Serpent PeopleJoao JoseNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To The Philosophy of The Human Person Quarter I - Module 2Documento26 pagineIntroduction To The Philosophy of The Human Person Quarter I - Module 2Katrina TulaliNessuna valutazione finora

- MEC332-MA 3rd Sem - Development EconomicsDocumento9 pagineMEC332-MA 3rd Sem - Development EconomicsRITUPARNA KASHYAP 2239239Nessuna valutazione finora

- Interview Question SalesforceDocumento10 pagineInterview Question SalesforcesomNessuna valutazione finora

- Optitex Com Products 2d and 3d Cad SoftwareDocumento12 pagineOptitex Com Products 2d and 3d Cad SoftwareFaathir Reza AvicenaNessuna valutazione finora