Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Leonard Bloomfield

Caricato da

Arun AhujaDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Leonard Bloomfield

Caricato da

Arun AhujaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Leonard Bloomfield

Leonard Bloomfield (April 1, 1887 April 18, 1949) was an American linguist who led the development of structural linguistics in the United States during the 1930s and the 1940s. His influential textbook Language, published in 1933, presented a comprehensive description of American structural linguistics.[1] He made significant contributions to Indo-European historical linguistics, the description of Austronesian languages, and description of languages of the Algonquian family. Bloomfield's approach to linguistics was characterized by its emphasis on the scientific basis of linguistics, adherence to behaviorism especially in his later work, and emphasis on formal procedures for the analysis of linguistic data. The influence of Bloomfieldian structural linguistics declined in the late 1950s and 1960s as the theory of Generative Grammar developed by Noam Chomsky came to predominate.

Early life and education

Bloomfield was born in Chicago, Illinois on April 1, 1887. His father Sigmund Bloomfield immigrated to the United States as a child in 1868; the original family name Blumenfeld was changed to Bloomfield after their arrival in the United States.[2] In 1896 his family moved to Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, where he attended elementary school, but returned to Chicago for secondary school.[3] His uncle Maurice Bloomfield was a prominent linguist at Johns Hopkins University,[4][5] and his aunt Fannie Bloomfield Zeisler was a well-known concert pianist.[4] Bloomfield attended Harvard College from 1903 to 1906, graduating with the A.B. degree.[5] He subsequently began graduate work at the University of WisconsinMadison, taking courses in German and Germanic philology, in addition to courses in other Indo-European languages.[6] A meeting with Indo-Europeanist Eduard Prokosch, a faculty member at the University of Wisconsin, convinced Bloomfield to pursue a career in linguistics.[5] In 1908 Bloomfield moved to the University of Chicago where he took courses in German and IndoEuropean philology with Frances A. Wood and Carl Darling Buck. His doctoral dissertation in Germanic historical linguistics was supervised by Wood, and he graduated in 1909. He undertook further studies at the University of Leipzig and the University of Gttingen in 1913 and 1914 with leading Indo-Europeanists August Leskien, Karl Brugmann, as well as Hermann Oldenberg, a specialist in Vedic Sanskrit. Bloomfield also studied at Gttingen with Sanskrit specialist Jacob Wackernagel, and considered both Wackernagel and the Sanskrit grammatical tradition of rigorous grammatical analysis associated with Pini as important influences on both his historical and descriptive work.[7][8] Further training in Europe was a condition for promotion at the University of Illinois from Instructor to the rank of Assistant Professor.[9]

Career

Bloomfield was Instructor in German at the University of Cincinnati, 19091910; Instructor in German at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 19101913; Assistant Professor of Comparative Philology and German, also University of Illinois, 19131921; Professor of German and Linguistics at the Ohio State University, 19211927; Professor of

Germanic Philology at the University of Chicago, 19271940; Sterling Professor of Linguistics at Yale University, 1940-1949. During the summer of 1925 Bloomfield worked as Assistant Ethnologist with the Geological Survey of Canada in the Canadian Department of Mines, undertaking linguistic field work on Plains Cree; this position was arranged by Edward Sapir, who was then Chief of the Division of Anthropology, Victoria Museum, Geological Survey of Canada, Canadian Department of Mines.[10][11] Bloomfield was one of the founding members of the Linguistic Society of America. In 1924, along with George M. Bolling (Ohio State University) and Edgar Sturtevant (Yale University) he formed a committee to organize the creation of the Society, and drafted the call for the Society's foundation.[12][13] He contributed the lead article to the inaugural issue of the Society's journal Language,[14] and was President of the Society in 1935.[15] He taught in the Society's summer Linguistic Institute in 1938-1941, with the 1938-1940 Institutes being held in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and the 1941 Institute in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.[16]

Indo-European linguistics

Bloomfield's earliest work was in historical Germanic studies, beginning with his dissertation, and continuing with a number of papers on Indo-European and Germanic phonology and morphology.[17][18] His post-doctoral studies in Germany further strengthened his expertise in the Neogrammarian tradition, which still dominated Indo-European historical studies.[19] Bloomfield throughout his career, but particularly during his early career, emphasized the Neogrammarian principle of regular sound change as a foundational concept in historical linguistics.[14][20] Bloomfield's work in Indo-European beyond his dissertation was limited to an article on palatal consonants in Sanskrit[21] and one article on the Sanskrit grammatical tradition associated with Pini,[22] in addition to a number of book reviews. Bloomfield made extensive use of Indo-European materials to explain historical and comparative principles in both of his textbooks, An introduction to language (1914), and his seminal Language (1933).[23] In his textbooks he selected Indo-European examples that supported the key Neogrammarian hypothesis of the regularity of sound change, and emphasized a sequence of steps essential to success in comparative work: (a) appropriate data in the form of texts which must be studied intensively and analysed; (b) application of the comparative method; (c) reconstruction of proto-forms.[23] He further emphasized the importance of dialect studies where appropriate, and noted the significance of sociological factors such as prestige, and the impact of meaning.[24] In addition to regular linguistic change, Bloomfield also allowed for borrowing and analogy.[25] It is argued that Bloomfield's Indo-European work had two broad implications: "He stated clearly the theoretical bases for Indo-European linguistics..."; and "...he established the study of Indo-European languages firmly within general linguistics...."[26]

Sanskrit studies

As part of his training with leading Indo-Europeanists in Germany in 1913-1914 Bloomfield studied the Sanskrit grammatical tradition originating with Pini, who lived in northwestern India during the sixth century B.C.[27] Pini's grammar is characterized by its extreme thoroughness and explicitness in accounting for Sanskrit linguistic forms. Bloomfield noted

that "Pini gives the formation of every inflected, compounded, or derived word, with an exact statement of the sound-variations (including accent) and of the meaning."[28] In a letter to Algonquianist Truman Michelson, Bloomfield noted "My models are Pini and the kind of work done in Indo-European by my teacher, Professor Wackernagel of Basle."[29] Pini's systematic approach to analysis includes components for: (a) forming grammatical rules, (b) an inventory of sounds, (c) a list of verbal roots organized into sublists, and (d) a list of classes of morphs.[30] Bloomfield's approach to key linguistic ideas in his textbook Language reflect the influence of Pini in his treatment of basic concepts such as linguistic form, free form, and others. Similarly, Pini is the source for Bloomfield's use of the terms exocentric and endocentric used to describe compound words.[31] Concepts from Pini are found in Eastern Ojibwa, published posthumously in 1958, in particular his use of the concept of a morphological zero, a morpheme that has no overt realization.[32] Pini's influence is also present in Bloomfield's approach to determining parts of speech (Bloomfield uses the term 'form-classes') in both Eastern Ojibwa and in the later Menomini language, published posthumously in 1962.[33]

Austronesian linguistics

While at the University of Illinois Bloomfield undertook research on Tagalog, an Austronesian language spoken in the Philippines. He carried out linguistic field work with Alfredo Viola Santiago, who was an engineering student at the university from 1914-1917. The results were published as Tagalog texts with grammatical analysis, which includes a series of texts dictated by Santiago in addition to an extensive grammatical description and analysis of every word in the texts.[34] Bloomfields work on Tagalog, from the beginning of field research to publication, took no more than two years.[35] His study of Tagalog has been described as the best treatment of any Austronesian languageThe result is a description of Tagalog which has never been surpassed for completeness, accuracy, and wealth of exemplification.[36] Bloomfield's only other publication on an Austronesian language was an article on the syntax of Ilocano, based upon research undertaken with a native speaker of Ilocano who was a student at Yale University. This article has been described as a "tour de force, for it covers in less than seven pages the entire taxonomic syntax of Ilocano."[37][38]

Algonquian linguistics

Bloomfields work on Algonquian languages had both descriptive and comparative components. He published extensively on four Algonquian languages: Fox, Cree, Menominee, and Ojibwe, publishing grammars, lexicons, and text collections. Bloomfield used the materials collected in his descriptive work to undertake comparative studies leading to the reconstruction of Proto-Algonquian, with an early study reconstructing the sound system of Proto-Algonqian,[39] and a subsequent more extensive paper refining his phonological analysis and adding extensive historical information on general features of Algonquian grammar.[40] Bloomfield undertook field research on Cree, Menominee, and Ojibwe, and analysed the material in previously published Fox text collections. His first Algonquian research, beginning around 1919, involved study of text collections in the Fox language that had been

published by William Jones and Truman Michelson.[41][42] Working through the texts in these collections, Bloomfield excerpted grammatical information to create a grammatical sketch of Fox.[43] A lexicon of Fox based on his excerpted material was published posthumously.[44] Bloomfield undertook field research on Menominee in the summers of 1920 and 1921, with further brief field research in September 1939 and intermittent visits from Menominee speakers in Chicago in the late 1930s, in addition to correspondence with speakers during the same period.[45] Material collected by Morris Swadesh in 1937 and 1938, often in response to specific queries from Bloomfield, supplemented his information.[46] Significant publications include a collection of texts,[47] a grammar and a lexicon (both published posthumously),[48][49] in addition to a theoretically significant article on Menomini phonological alternations.[50] Bloomfield undertook field research in 1925 among Plains Cree speakers in Saskatchewan at the Sweet Grass reserve, and also at the Star Blanket reserve, resulting in two volumes of texts and a posthumous lexicon.[51][52][53] He also undertook brief field work on Swampy Cree at The Pas, Manitoba. Bloomfield's work on Swampy Cree provided data to support the predictive power of the hypothesis of exceptionless phonological change.[20] Bloomfield's initial research on Ojibwe was through study of texts collected by William Jones, in addition to nineteenth century grammars and dictionaries.[54][55] During the 1938 Linguistic Society of America Linguistic Institute held at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan, he taught a field methods class with Andrew Medler, a speaker of the Ottawa dialect who was born in Saginaw, Michigan but spent most of his life on Walpole Island, Ontario. The resulting grammatical description, transcribed sentences, texts, and lexicon were published posthumously in a single volume.[56] In 1941 Bloomfield worked with Ottawa dialect speaker Angeline Williams at the 1941 Linguistic Institute held at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, resulting in a posthumously published volume of texts.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Peter Ghosh - Max Weber and 'The Protestant Ethic' - Twin Histories-Oxford University Press (2014) PDFDocumento421 paginePeter Ghosh - Max Weber and 'The Protestant Ethic' - Twin Histories-Oxford University Press (2014) PDFvkozaevaNessuna valutazione finora

- Phonemes and Allophones - Minimal PairsDocumento5 paginePhonemes and Allophones - Minimal PairsVictor Rafael Mejía Zepeda EDUCNessuna valutazione finora

- Paper Phonetics FinalDocumento3 paginePaper Phonetics FinalFarooq Ali KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Phonetics & Phonology: LANG 4402Documento39 paginePhonetics & Phonology: LANG 4402Nguyễn Phương NhungNessuna valutazione finora

- PhoneticsDocumento25 paginePhoneticsNisrina AthirahNessuna valutazione finora

- William M.A. Grimaldi-Aristotle, Rhetoric I. A Commentary - Fordham University Press (1980)Documento368 pagineWilliam M.A. Grimaldi-Aristotle, Rhetoric I. A Commentary - Fordham University Press (1980)racoonic100% (3)

- Definition of GrammarDocumento3 pagineDefinition of GrammarBishnu Pada Roy0% (1)

- Unit 4 PhoneticsDocumento15 pagineUnit 4 Phoneticsmjgvalcarce100% (4)

- Sociolinguistics in Language TeachingDocumento101 pagineSociolinguistics in Language TeachingNurkholish UmarNessuna valutazione finora

- VARIETIES OF ENGLISHDocumento28 pagineVARIETIES OF ENGLISHStella Ramirez-brownNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding the Relationship Between Language and SocietyDocumento48 pagineUnderstanding the Relationship Between Language and Societydianto pwNessuna valutazione finora

- Connected SpeechDocumento4 pagineConnected SpeechMaría CarolinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sociolinguistics: "Society On Language" "Language Effects On Society"Documento3 pagineSociolinguistics: "Society On Language" "Language Effects On Society"Bonjovi HajanNessuna valutazione finora

- Historical Semantics: Michel BréalDocumento5 pagineHistorical Semantics: Michel Bréalginanjar satrio utomoNessuna valutazione finora

- Principles of E Phonetics and PhonologyDocumento74 paginePrinciples of E Phonetics and PhonologyDuy NguyễnNessuna valutazione finora

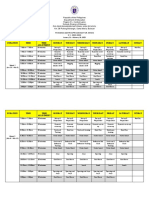

- Arnis Traning Matrix 2023Documento6 pagineArnis Traning Matrix 2023RA CastroNessuna valutazione finora

- Historical Linguistics - Genetic ClassificationDocumento33 pagineHistorical Linguistics - Genetic ClassificationKhalil Brahimi100% (1)

- Pass4sure 400-101Documento16 paginePass4sure 400-101Emmalee22Nessuna valutazione finora

- 1.concept of LanguageDocumento19 pagine1.concept of LanguageIstiqomah BonNessuna valutazione finora

- Presentation SociolinguisticsDocumento17 paginePresentation Sociolinguisticsmehdi67% (3)

- OMSC Learning Module on the Contemporary WorldDocumento105 pagineOMSC Learning Module on the Contemporary WorldVanessa EdaniolNessuna valutazione finora

- Lecture - 10. Phonetics LectureDocumento78 pagineLecture - 10. Phonetics LectureMd Abu Kawser SajibNessuna valutazione finora

- Digital Transformation For A Sustainable Society in The 21st CenturyDocumento186 pagineDigital Transformation For A Sustainable Society in The 21st Centuryhadjar khalNessuna valutazione finora

- DialectDocumento7 pagineDialectBryant AstaNessuna valutazione finora

- Student Interest SurveyDocumento7 pagineStudent Interest Surveymatt1234aNessuna valutazione finora

- Generative Phonology: Description and TheoryDa EverandGenerative Phonology: Description and TheoryValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (4)

- TeambuildingDocumento18 pagineTeambuildingsamir2013100% (1)

- Jakobsonian's and Chomskyan's Distinctive Feature of PhonologyDocumento4 pagineJakobsonian's and Chomskyan's Distinctive Feature of PhonologyFrancis B. Tatel100% (1)

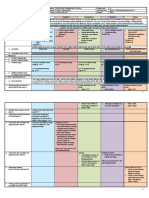

- LAC PLAN 2023 2024.newDocumento3 pagineLAC PLAN 2023 2024.newrosemarie lozada78% (9)

- BloomfieldDocumento3 pagineBloomfieldLaissaoui FarhatNessuna valutazione finora

- Week 2 Morphology and SyntaxDocumento7 pagineWeek 2 Morphology and SyntaxAnnisa RahmadhaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Ling 329: MorphologyDocumento5 pagineLing 329: MorphologyJonalyn ObinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Meaning of LanguageDocumento17 pagineMeaning of LanguageLance Arkin AjeroNessuna valutazione finora

- Notes On Linguistic VarietiesDocumento18 pagineNotes On Linguistic Varietiesahmadkamil94Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sound Assimilation in English and Arabic A Contrastive Study PDFDocumento12 pagineSound Assimilation in English and Arabic A Contrastive Study PDFTaha TmaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Classification and Description of Speech Sounds in English LanguageDocumento6 pagineThe Classification and Description of Speech Sounds in English LanguageNaeemNessuna valutazione finora

- Grammar: PDF Generated At: Sun, 12 Aug 2012 13:23:53 UTCDocumento34 pagineGrammar: PDF Generated At: Sun, 12 Aug 2012 13:23:53 UTCSri Krishna Kumar0% (1)

- Suprasegmental PhonologyDocumento2 pagineSuprasegmental PhonologyValentina CandurinNessuna valutazione finora

- Overview of English Linguistics CompilationDocumento10 pagineOverview of English Linguistics CompilationIta Moralia RaharjoNessuna valutazione finora

- Are Languages Shaped by Culture or CognitionDocumento15 pagineAre Languages Shaped by Culture or Cognitioniman22423156Nessuna valutazione finora

- Linguistic AreaDocumento16 pagineLinguistic AreaEASSANessuna valutazione finora

- Phonemes Distinctive Features Syllables Sapa6Documento23 paginePhonemes Distinctive Features Syllables Sapa6marianabotnaru26Nessuna valutazione finora

- Theories of Semantic Change Three ApproaDocumento13 pagineTheories of Semantic Change Three ApproaAlbert Albert0% (1)

- English Consonant Sounds for Spanish SpeakersDocumento6 pagineEnglish Consonant Sounds for Spanish SpeakersJazmin SanabriaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter I Language, Culture, and SocietyDocumento8 pagineChapter I Language, Culture, and SocietyJenelyn CaluyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Transformational-Generative Grammar: (Theoretical Linguistics)Documento46 pagineTransformational-Generative Grammar: (Theoretical Linguistics)Les Sirc100% (1)

- Introduction To LinguisticsDocumento11 pagineIntroduction To LinguisticsElmehdi MayouNessuna valutazione finora

- Linguistics: A ĀdhyāyīDocumento2 pagineLinguistics: A ĀdhyāyīNevena JovanovicNessuna valutazione finora

- The Saussurean DichotomiesDocumento10 pagineThe Saussurean DichotomiesHerpert ApthercerNessuna valutazione finora

- The syllable in generative phonologyDocumento4 pagineThe syllable in generative phonologyAhmed S. MubarakNessuna valutazione finora

- Bloomfield Lecture For StudentsDocumento4 pagineBloomfield Lecture For StudentsNouar AzzeddineNessuna valutazione finora

- Structural Ambiguity of EnglishDocumento18 pagineStructural Ambiguity of EnglishthereereNessuna valutazione finora

- LING 60 Syllable Structure and Phonological ProcessesDocumento15 pagineLING 60 Syllable Structure and Phonological ProcessesNome PrimaNessuna valutazione finora

- High German Consonant ShiftDocumento10 pagineHigh German Consonant ShiftJuan Carlos Moreno HenaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Types of Word Formation ProcessesDocumento6 pagineTypes of Word Formation ProcessesMuhamad FarhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Biographical Study of LiteratureDocumento5 pagineBiographical Study of Literatureapi-294041566Nessuna valutazione finora

- Modern Linguistics: European StructuralismDocumento4 pagineModern Linguistics: European StructuralismCélia ZENNOUCHE100% (1)

- English Phonetic and Phonology (Syllables)Documento8 pagineEnglish Phonetic and Phonology (Syllables)NurjannahMysweetheart100% (1)

- Major Approaches To Discourse AnalysisDocumento3 pagineMajor Approaches To Discourse AnalysisBestil AyNessuna valutazione finora

- A Brief History of Early Linguistics of The 18th and 19th CenturyDocumento4 pagineA Brief History of Early Linguistics of The 18th and 19th CenturyKevin Stein100% (3)

- ElisionDocumento4 pagineElisionTahar MeklaNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal Long VowelsDocumento9 pagineJournal Long VowelsEcha IkhsanNessuna valutazione finora

- Phonological Contrastive Analysis of Arabic, Turkish and EnglishDocumento9 paginePhonological Contrastive Analysis of Arabic, Turkish and EnglishMorteza YazdaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Neologisms & TranslationDocumento14 pagineNeologisms & TranslationLuis Diego MarínNessuna valutazione finora

- Thematic RolesDocumento8 pagineThematic RolesCrosslinguisticNessuna valutazione finora

- Power Point 1 MorphologyDocumento12 paginePower Point 1 MorphologyGilank WastelandNessuna valutazione finora

- Assimilation of Consonants in English and Assimilation of The Definite Article in ArabicDocumento7 pagineAssimilation of Consonants in English and Assimilation of The Definite Article in Arabicابو محمدNessuna valutazione finora

- Scandinavian InfluenceDocumento10 pagineScandinavian InfluenceAnusmita MukherjeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Manual For Project Report and GuidanceDocumento17 pagineManual For Project Report and GuidanceJessy CherianNessuna valutazione finora

- Math Inquiry LessonDocumento4 pagineMath Inquiry Lessonapi-409093587Nessuna valutazione finora

- 18TH AmendmenntDocumento36 pagine18TH AmendmenntMadiha AbbasNessuna valutazione finora

- Curriculum Management in Korea PDFDocumento9 pagineCurriculum Management in Korea PDFNancy NgNessuna valutazione finora

- Operations Management Managing Global Supply Chains 1st Edition Venkataraman Solutions ManualDocumento32 pagineOperations Management Managing Global Supply Chains 1st Edition Venkataraman Solutions Manualburgee.dreinbwsyva100% (45)

- J.B. WatsonDocumento14 pagineJ.B. WatsonMuhammad Azizi ZainolNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 10 Transfer of Training 10.11.15Documento45 pagineChapter 10 Transfer of Training 10.11.15Nargis Akter ToniNessuna valutazione finora

- Savitribai Phule Pune University, Online Result PDFDocumento1 paginaSavitribai Phule Pune University, Online Result PDFshreyashNessuna valutazione finora

- Sehrish Yasir2018ag2761-1-1-1Documento97 pagineSehrish Yasir2018ag2761-1-1-1Rehan AhmadNessuna valutazione finora

- Foundations of Government Management: Muddling Through IncrementallyDocumento4 pagineFoundations of Government Management: Muddling Through IncrementallyAllan Viernes100% (1)

- The 20 Point ScaleDocumento7 pagineThe 20 Point ScaleTinskiweNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 2 - Nature of ResearchDocumento11 pagineLesson 2 - Nature of ResearchRuben Rosendal De Asis100% (1)

- Proceedings of ICVL 2016 (ISSN 1844-8933, ISI Proceedings)Documento416 pagineProceedings of ICVL 2016 (ISSN 1844-8933, ISI Proceedings)Marin VladaNessuna valutazione finora

- Trends, Networks, and Critical Thinking in the 21st CenturyDocumento21 pagineTrends, Networks, and Critical Thinking in the 21st CenturyJessie May CaneteNessuna valutazione finora

- On The Integer Solutions of The Pell Equation: M.A.Gopalan, V.Sangeetha, Manju SomanathDocumento3 pagineOn The Integer Solutions of The Pell Equation: M.A.Gopalan, V.Sangeetha, Manju SomanathinventionjournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- DLL Epp6-Entrep q1 w3Documento3 pagineDLL Epp6-Entrep q1 w3Kristoffer Alcantara Rivera50% (2)

- TARA Akshar+: Adult ProgrammeDocumento4 pagineTARA Akshar+: Adult ProgrammesilviaNessuna valutazione finora

- FEU Intro to Architectural Visual 3 and One Point PerspectiveDocumento2 pagineFEU Intro to Architectural Visual 3 and One Point Perspectiveangelle cariagaNessuna valutazione finora

- 3f48a028-bc42-4aa4-8a05-6cf92f32955aDocumento15 pagine3f48a028-bc42-4aa4-8a05-6cf92f32955ahoyiNessuna valutazione finora

- Luzande, Mary Christine B ELM-504 - Basic Concepts of Management Ethics and Social ResponsibilityDocumento12 pagineLuzande, Mary Christine B ELM-504 - Basic Concepts of Management Ethics and Social ResponsibilityMary Christine BatongbakalNessuna valutazione finora

- UCL Intro to Egyptian & Near Eastern ArchaeologyDocumento47 pagineUCL Intro to Egyptian & Near Eastern ArchaeologyJools Galloway100% (1)