Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Krispy Kreme

Caricato da

Heo MapDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Krispy Kreme

Caricato da

Heo MapCopyright:

Formati disponibili

III. OBJECTIVES a. To gradually gain back analysts, investors and lenders confidence in the company in the succeeding months.

b. To increase sales and profitability in terms of its core business, selling of doughnuts. c. To regain and increase stock price therefore increasing shareholder value. d. To correct inaccurate entries in the financial statements of KKD and to present a clean and unbiased reports. e. To extend further reach to consumers strategically to achieve significant growth in the next five years. f. To implement extensive marketing measures for its brand and products and investment strategy for both on and off premise operations. IV. AREAS OF CONSIDERATION Fortune magazine had dubbed Krispy Kreme Doughnut, Inc. the hottest brand in America. With ambitious plans to open 500 doughnut shops over the first half of the decade. The company generated revenues through four primary sources: on-premise retail sales at company owned stores (27% of revenues), off-premises sales to grocery and convenience stores (40%); manufacturing and distribution of product mix and machinery (29%); and franchise royalties and fees (4%). Roughly 60% of sales at a Krispy Kreme store were derived from the companys signature product, the glazed doughnut. On May 7, 2004, Krispy Kreme announced adverse results. The company told investors to expect earnings to be 10% lower than anticipated, claiming that the recent low-carbohydrate diet trend in the United States had hurt wholesale and retail sales. The company also said it planned to divest Montana Mills and would take a charge of $35 million to $40 million. According to the Wall Street Journal, the company recorded the interest paid by the franchisee as interest income and, thus, as immediate profit; however, the company booked the purchase cost of the franchise as an intangible asset which the company did not amortize. Over the previous 3 years, the company had recorded $174.5 million as intangible assets (reacquired franchise rights), which the company was not required to amortize. Kripy Kremes shares fell another 15%, closing at $15.71 a share.

By the time the Wall Street Journal published the article in May 2004, only 25% of the analysts were recommending the company as a buy; 50% had downgraded to a hold. Another issue is that the company has relied for a significant chunk of profits on high profitmargin equipment that it requires franchisees to buy for each new store. Its profits have also been tied to growth in the number of franchised store

Financial Analysis And Forecasting For Kkd

The Fall of Krispy Kreme Donuts

MBA 6154 - Dr. Plath By: Jon Plyler Luke Sagur Introduction Since its IPO in April 2000, Krispy Kreme grew to be a top pick of Wall Street Analysts. The companys growth seemed unstoppable and Krispy Kreme was able to beat Wall Streets expectations. Krispy Kreme continued to outperform until 2004 when some accounting woes were brought to light and analysts starting noticing other anomalies that indicated that things were not quite as good as they seemed. The firms stock price quickly plummeted from its peak and lost more than 80 percent of its value in only 16 months. This case study focuses on the use of financial statement analysis, and other factors that an equity analyst would use to gauge the health of a firm, to help identify symptoms that demonstrate things where not as good as they seemed at Krispy Kreme. The report starts by introducing Krispy Kreme, their history, structure and strategy. We will then discuss Krispy Kreme's financials and other tell tales that were available to predict the demise of the firm. To wrap up the report we will conclude by summarizing all the signs that demonstrated things were amiss and answer the question: "Can financial statement analysis predict the future?" Krispy Kreme History Krispy Kreme began as a small business in Winston Salem, North Carolina in 1937 shortly after the companys founder, Vernon Rudolph, purchased a doughnut recipe from a French chef from New Orleans. Krispy Kreme was initially a doughnut wholesaler that sold its products directly to supermarkets. Krispy Kreme doughnuts were such a hit with consumers that Rudolph decided to make them available at the factory, an idea that led to what many people find so appealing about

Krispy Kreme, the factory store concept. Rudolph franchised the business which helped Krispy Kreme to spread into 12 states with 29 shops by the late 1950s. Krispy Kreme was sold to Beatrice Foods in 1973 after Rudolphs death. Beatrice added more products to their Krispy Kreme menu, such as soups and sandwiches and at the same time enacted cost-cutting measures by changing store design and using cheaper ingredients in the doughnuts. The introduction of new products and lower quality doughnuts was not a hit with customers. The vision Beatrice had for Krispy Kreme was failing and the decision was made to sell franchise. In 1982 a group of investors led by one of the original Krispy Kreme franchisees, Joseph McAleer, completed a leveraged buyout of Krispy Kreme from Beatrice and quickly began to return it to its roots, mainly by reverting to the original doughnut recipe and signage. Six years later the company was free of debt and beginning to expand. In the spring of 2000 Krispy Kreme, amidst much fanfare and market excitement, went public with a high profile IPO. The Krispy Kreme Model The heart of the Krispy Kreme concept is the factory store, or Doughnut Theater experience, where customers can see the doughnuts being made and consume one just seconds after it comes off the conveyor belt. The Hot Doughnuts Now sign, when illuminated, alerts passersby to the fact that hot doughnuts are available. The average factory store can produce as many as 10,000 doughnuts in a day, most of which are sold off-premises to local convenient stores and grocery stores. Approximately 27 percent of sales revenue are attributed to on-premises sales and 40 percent are attributed to off-premises sales. Figure 1 gives a graphical representation of Krispy Kreme's revenue streams. [pic] Figure 1 Another large revenue source is the KKM&D division which manufactures and distributes the raw ingredients, doughnut making machinery, and coffee. All stores, both company owned and franchised owned, must purchase these products from KKM&D. This allows Krispy Kreme to maintain tight control on quality. The KKM&D division accounts for approximately 27 percent of total Krispy Kremes revenue. Krispy Kreme is very dependent on franchisees for expansion into new markets. Franchisees that were in business before the IPO are considered as Krispy Kreme associates while new franchisees are considered Area Developers. The associates were able to carry on with business as usual but the Area Developers are responsible for helping to grow the business. Each Area Developers incur a one-time franchise fee of up to $50,000 then pay up to 6% of sales to Krispy

Kreme as a royalty and 1% of annual sales as an advertising fee. The franchise royalties account for approximately 4% of Krispy Kremes revenue. Krispy Kreme By The Numbers: Financial Statement Analysis Krispy Kremes investors enjoyed a quick return on their investment after the IPO. By the end of 2000 the stock price had doubled, then shot to a high of 4.5x the IPO price by mid-2001. Krispy Kreme was one of the new glamour stocks on Wall Street, but from the standpoint of an educated investor was it healthy enough to support the success of its stock? An analysis of the Krispy Kreme financials should give some insight into the health of the company. Krispy Kremes revenue increased every year between 2000 and 2004, from $220m to over $665m. Along with growing revenues, the operating and net profit margins also increased every year. The operating margin increased from just under 4% in 2000 to over 15% by the end of 2004 and the net profit margin increased from just under 3% to over 8% during the same time period. The ROA and ROE though the time period were relatively steady at an average of 8.28% and 12.62% respectively. Krispy Kremes liquidity remained relatively constant from 2000 to 2002, but quickly increasing. By 2004 Krispy Kreme had quick and current ratios of 2.72x and 3.25x respectively and an interest coverage ratio of 23x. From these numbers it did appear that Krispy Kreme was able to maintain a very liquid position and grow rapidly without the use of much debt. As with any ratio analysis, the ratios themselves cannot give the insight needed to fully evaluate the health of the company. To properly evaluate the ratios of a particular company the ratios must be compared to those if its peers. In this case Krispy Kremes metrics are compared to others in the quick service restaurant sector. This comparison shows a few interesting anomalies. Both the quick ratio and current ratio are double those of the other companies. Furthermore, the Krispy Kreme leverage ratios are out of line with those of its peers; its long term debt to equity is 11.26% compared to an average of 53.1% of its peer's. This fact supports what was seen previously, that Krispy Kreme was growing without taking on much debt. The interest coverage ratio was also much higher 23.15% compared to 8.25% which also indicates that they were not highly leveraged. While Krispy Kremes ratios were not in line with the peer averages, they were able to maintain an ROA and ROE that was on par with the competition. The case provides a comparison of Krispy Kremes 2003 balance sheet to that of the limited service restaurant average. It is immediately noticed that Krispy Kreme has a trade receivables on the order of 10x that of the industry average which appears to be the receivables from the sale of raw material and equipment to the franchisees through KKM&D. Also, the Krispy Kreme intangibles are over 2x the industry average. On the liability side Krispy Kreme has very little short term debt compared to the competitors, 7x less long term debt which indicates a low level of financial leveraging. Upon further review of the Krispy Kreme balance sheets between 2000 and 2004 and comparing year end snapshots there appears to be a trend of franchise buy backs.

The intangible category reacquired franchise rights on the asset side of the balance sheet begins to increase during the 2002 fiscal year and grows quickly, especially during the 2004 fiscal year. At the same time, there was no corresponding change in amortization on the income statement. From the analysis of the financials it appears that the very high trade receivables, high liquidity and interest coverage ratio, along with low financial leverage indicate that Krispy Kreme may have been using the franchisees to bankroll the growth of the company. Krispy Kreme's Franchise Strategy Many of the ratios and metrics from the financial data analysis points to the fact that Krispy Kreme was doing something different in regards to how it handled franchise relative to other comparable franchise companies. Krispy Kreme's franchise strategy focuses around selling equipment and supplies, including ingredients to their franchises at high margins. This is a stark contrast to the more standard franchising strategy where firms would build the business around franchise royalty payments and receive a percentage of the sales. This more standard strategy clearly aligns the interests of the corporation with those of the franchises. Krispy Kreme's model does have some advantages as they could push all the financing costs of growth onto the franchise owners and off the books of the firm. This is evident in Krispy Kreme's debt ratio's that are far lower then comparable firms and helps explain how they were able to grow so fast. This method also insures that all stores are similar and offers a way to control the quality of its products across all its stores. The disadvantage of this type of model is that it does not tie the interests of the corporation to those of the franchise creating "goal conflict" between the two parties. This propensity was obvious in many moves that Krispy made during its rapid growth during the years of 2000- 2004. Under the pressure to grow quickly, Krispy Kreme took full advantage of its structure and focused heavily at growing profits at the parent-company level while sacrificing performance at the franchise level. [pic] Figure 2 Figure 2 illustrates how Krispy Kreme focused its growth on expanding its number of stores, receiving income from the high margin equipment and supplies, while sacrificing same store sales. The initial equipment package for a store would sell for $770,000 with a margin on the order of 20 percent. This strategy eventually ended up saturating the market which led to the need to re-purchase struggling stores that couldn't make their payments on the equipment they purchased. Krispy Kreme took this a step further and took further advantage of this structure. In times where Krispy Kreme was in danger of missing their numbers, they would force franchises to purchase new equipment they really didn't need. Krispy Kreme booked an immediate profit from these sales, but didn't require the franchise to pay for the equipment until it was installed and put to use which would sometimes be months down the road. There were also some examples where the

corporation would force the sales of ingredients near the end of quarters and would then allow the franchise to sell it back to them early in the following quarter. Accounting for Reacquisition of Franchises Another problem that Krispy Kreme faced was how it handled reacquisition of franchises. In the years leading up to Krispy Kremes fall, they reacquired several franchises in various locations and used questionable accounting practices to do so. Typically when a company reacquires a franchise they will amortize those costs over time. When Krispy Kreme reacquired several franchises it treated more that 85% of the purchase as "reacquired franchise rights", an intangible, which it did not have to amortize. Accounting for the reacquisition in this manor offered several advantages that boosted the bottom line. First, the acquisition of the franchises created an immediate boost to the income statement as the sales from these stores went straight to income. Secondly, not having to amortize 85% of the purchase meant that Krispy Kreme was not required to charge a portion of the purchase as an amortization expense against the income it received from the stores essentially "super charging" its profits. Thirdly, by accounting for the purchases in this manor, Krispy Kreme was able to carry the cost of "reacquiring franchise rights" as an intangible that remains on the asset side of the balance sheet, boosting the firms assets. Figure 3 below is a simple example that illustrates the benefits of this style of accounting. In this case the Krispy Kreme accounting method only amortizes 15% of the purchase price while the more accepted approach amortizes 100% of the store purchase price. The result is an increase in profits of $56,667 which boosts the profit margin of the store from 13% to 19% demonstrating how this type of accounting can "super charge" the profits. [pic] Figure 3 According to analysts, this accounting is definitely not conservative and stretches accounting rules to the limit (Brooks 2004). Along with amortization discrepancies Krispy Kreme also mishandled two other facets of reacquiring franchises. Often times they would purchase the franchises for inflated prices so that the franchise owner could use this additional money to pay back debt to Krispy Kreme. This payment could then be booked as an immediate profit on Krispy Kreme's books. The final questionable practice in regards to Krispy Kreme's reacquisition of franchises deals with compensation of franchise owners and the expense of closing stores. In the case of Krispy Kreme reacquiring seven stores in Michigan, Krispy Kreme booked the salary expense of keeping the owner on as a consultant and the cost of closing the store as a intangible cost, part of the "reacquired franchise rights". Handling these charges in this manor allowed Krispy Kreme to boost its assets and decrease expenses.

Signs of demise from Management structure and behavior Along with the signs that showed that things were amiss on Krispy Kreme's financials, several factors existed within the firm's management structure. Behavior also showed cause for concern. There were many signs of weak governance at Krispy Kreme that led to a lack of internal controls. The board for one was mainly constructed of board members who were left over from the days in which Krispy Kreme was a privately held company and many of those members owned Krispy Kreme franchises. Secondly the CEO Scott Livengood's total compensation was more than 20 percent higher then the median of companies of similar-size pointed to signs of weak governance. Scott was also awarded a 6-month consultant role upon his retirement where he received a salary of $275,000 plus benefits. The compensation of the management team at Krispy Kreme was very heavily weighted on the team meeting EPS guidance. In fact around 2003 the incentives plan for senior executives was modified such that no bonuses to officers would be paid unless the company was able to exceed EPS guidance each quarter by one penny. Coincidentally it has been reported that Krispy Kreme has managed to exceed the consensus EPS quarterly guidance by exactly $0.01 in seven of the eight quarters leading up to the second quarter of fiscal 2004, along with beating guidance by at least $0.01 in all thirteen quarters since going public. Table 1 illustrates this point. [pic] Table 1 Monitoring inside trading was also a sign that things were not as good as they seems at Krispy Kreme. In total, insiders have sold $267 million in stock since the IPO and Livengood sold 235,500 shared in August 2003. A week after the all-time high a few months after saying he wouldn't sell more stock for at least a year (the exact order was a limit order for $40/share generating over $9.4 million). Another point that should have been suspicious was the turnover of the CFO position that the firm experienced during 2000-2004. A total of four CFOs moved through the company at that time that should be us that something was amiss at the corporation. Most likely the CFO wasn't coming up with numbers that the rest of management didn't want to hear. Krispy Kreme Where are they now? In the years since 2004 Krispy Kreme has struggled and the stock price has never recovered. There was a glimmer of hope through 2006 and the stock showed steady increase in price but then it took a turn for the worse in 2007. Figure 4 shows the Krispy Kreme compared to the S&P 500 index. As of this writing the stock was trading at $3.01/share and experienced a 52wk low of $1.01/share which is a far cry from its high of nearly $50 in August of 2003. The annual net profit over the past 3 years has been negative and although there has been an improvement in

operating profit as of FY ending Feb. 2009 Krispy Kreme still shows a net loss. As of the second quarter of 2009 the outlook was not much better as they were still operating with a net loss. Things have also gotten worse for the Krispy Kreme leadership who were in command during the time of the case. In March of 2009 the SEC charged Scott Livengood, John Tate, and Randy Casstevens in a complaint that alleged the three men intentionally overstated profit in order to meet certain EPS targets, which their bonuses were depended upon. None of the men named in the complaint remain employed by Krispy Kreme. [pic] Figure 4 Conclusion As a publicly held company Krispy Kreme was able to consistently exceed the expectations of analysts and investors until its collapse in 2004. From the beginning of their journey as a publicly traded company Krispy Kreme's financial statements exhibited some clear differences compared to those if its peers. As the firm continued to grow even more suspicious behavior was identifiable in Krispy Kreme's financials. By the time Krispy Kreme announced it's earning in May 2004 many clues existed that thing were not as good as they seemed. Examining same store sales growth vs. store opening identified that Krispy Kreme was clearly saturating the market. The high liquidity, high trade receivables, and low financial leverage brought to light the fact that the debt was pushed onto the franchisees and that their franchise strategy created a conflict of interest between the goals of the corporate team and the franchisees. The growing intangible "reacquired franchise rights" and the fact that other franchises used much more conservative accounting for these types of transactions also threw up a red flag. In addition to the financial statement clues, other behaviors by management also pointed to issues with their company. The management compensation structure including a high CEO compensation package along with a high CFO turnover, the executive bonus structure, and the fact that they suspiciously beat Wall Streets expectations for EPS by one penny pointed to issues at Krispy Kreme. Combining these with the fact that many of board members were left over from the days when Krispy Kreme was a private firm and that many owned franchises point to the fact that there was little internal control. If an insightful analyst was able to identify all of these facts early enough in time they would have been able to inform their customers of disaster at hand and could have saved their customers lots of money. To answer the question can financial statement analysis predict the future, the answer is no, but it can raise some flags that something is amiss. The use of financial statement analysis and ratio analysis is a tool that can be use to spot symptoms of problems within the company. When interesting time trends in key accounting metrics are identified or key metrics differ considerably from other firms it is a sign that the company should be investigated further to get to the root

cause of the anomalies. A good example from this case is that the low debt ratios of Krispy Kreme leads you to the discovery that the company relied on franchises to finance the companies rapid growth. From this finding a savvy analyst could start to see the problem with their business model. Another import note to make is that when foul play in accounting is spotted and poor internal control is identified it's a good practice to stay away from the firm. In the majority of situations when one problem is spotted in a companies financials it often leads to others. Very seldom does a firm turn around quickly when accounting tinkering is identified, so the best practice is to cut your losses and get out as soon as any problems are identified in a companys finances. References: Brigham E., Ehrhardt M. Financial Management Theory and Practice 12th Edition, Thomson Southwestern, 2008 Craver R. Krispy Kreme on firm base but faces steep climb, stock experts Say. Winston Salem Journal, June 6 2009 Brooks R., Maremont M. Ovens Are Cooling At Krispy Kreme As Woes Multiply, Wall Street Journal, September 3, 2004. Bruner, Case Studies in Finance, The McGraw-Hill Companies, 2010 Krispy Kreme Company Website http://www.krispykreme.com O Sullivan K. Kremed, CFO Magazine June 1, 2005

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Krispy Kreme Doughnuts in 2005: Are The Glory Days Over?: Teaching NotesDocumento23 pagineKrispy Kreme Doughnuts in 2005: Are The Glory Days Over?: Teaching NotesAnonymous nj3pIshNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Analysis of Krispy Kreme DoughnutsDocumento5 pagineCase Analysis of Krispy Kreme DoughnutsKlaudine SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Group Assignment Module: Strategic Management Module Code: MGT620Documento37 pagineGroup Assignment Module: Strategic Management Module Code: MGT620nicolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Krispy Kreme Case StudyDocumento4 pagineKrispy Kreme Case StudyMike Crawford100% (1)

- Krispy Kreme Case Analysis Group IVDocumento5 pagineKrispy Kreme Case Analysis Group IVDung100% (2)

- KrispykremeDocumento41 pagineKrispykremekanza100% (2)

- Krispy Kreme Doughnuts IncDocumento247 pagineKrispy Kreme Doughnuts IncEndar P100% (1)

- Krispy Kreme Doughnuts-Suggested QuestionsDocumento1 paginaKrispy Kreme Doughnuts-Suggested QuestionsMohammed AlmusaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Krispy Kreme Case Study PDFDocumento6 pagineKrispy Kreme Case Study PDFashish borahNessuna valutazione finora

- Ateneo Multi-Purpose CooperativeDocumento32 pagineAteneo Multi-Purpose CooperativeBlessy DomerNessuna valutazione finora

- Krispy Kreme Analysis StratmanDocumento24 pagineKrispy Kreme Analysis StratmanMylene Visperas100% (1)

- Executive SummaryDocumento6 pagineExecutive SummaryFatema DawoodjiNessuna valutazione finora

- EPPM4014 Pengurusan Strategik: Chapter 5: Strategies in Action "Type of Strategies"Documento20 pagineEPPM4014 Pengurusan Strategik: Chapter 5: Strategies in Action "Type of Strategies"klein1988Nessuna valutazione finora

- Managerial EconomicsDocumento33 pagineManagerial EconomicsPrakhar SahayNessuna valutazione finora

- Krispy Kreme DonutDocumento17 pagineKrispy Kreme DonuthannahkisNessuna valutazione finora

- Krispy Kreme-Case Study Solution FinanceDocumento32 pagineKrispy Kreme-Case Study Solution FinanceHayat Omer Malik100% (3)

- REPUBLIC FLOUR MILLS CORPORATION - Financial AnalysisDocumento46 pagineREPUBLIC FLOUR MILLS CORPORATION - Financial Analysiskirt diazNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippine Christian UniversityDocumento4 paginePhilippine Christian UniversityMina SaflorNessuna valutazione finora

- Week 3 Case - Group 6Documento4 pagineWeek 3 Case - Group 6Kshitiz NeupaneNessuna valutazione finora

- New Era University: International Business PlanDocumento50 pagineNew Era University: International Business PlanNesly Ascaño CordevillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study FinalDocumento6 pagineCase Study FinalHelen Joan BuiNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study Htf735 (Fruit Smoothie) - 2Documento9 pagineCase Study Htf735 (Fruit Smoothie) - 2AfrinaNessuna valutazione finora

- CC1 Krispy Kreme Doughnuts Inc. 1Documento9 pagineCC1 Krispy Kreme Doughnuts Inc. 1JeanDianeJoveloNessuna valutazione finora

- Components of VMDocumento15 pagineComponents of VMNadine YbascoNessuna valutazione finora

- Manila Bulletin Publishing Corporation Sec Form 17a 2018Documento128 pagineManila Bulletin Publishing Corporation Sec Form 17a 2018Kathryn SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study Krispy Kreme Doughnut StrategyDocumento16 pagineCase Study Krispy Kreme Doughnut Strategyarvindmane100% (2)

- Group 2 Case 1 Krispy Kreme - FINALDocumento33 pagineGroup 2 Case 1 Krispy Kreme - FINALmishagabz100% (1)

- Philippine Long Distance TelephoneDocumento31 paginePhilippine Long Distance TelephoneAhnJelloNessuna valutazione finora

- A Customer-Focused Approach For Marketing MixDocumento8 pagineA Customer-Focused Approach For Marketing MixShouib MehreyarNessuna valutazione finora

- Krispy KremeDocumento21 pagineKrispy KremeMamun Rana100% (1)

- Final CB Term ReportDocumento60 pagineFinal CB Term ReportSaniya sohailNessuna valutazione finora

- Krispy KremeDocumento13 pagineKrispy KremeVikas Aggarwal100% (1)

- Chapter 7 - Cost-Volume-Profit AnalysisDocumento9 pagineChapter 7 - Cost-Volume-Profit AnalysisiamyunleNessuna valutazione finora

- Walmart Hoping For Another Big Holiday ShowingDocumento5 pagineWalmart Hoping For Another Big Holiday ShowingSuman MahmoodNessuna valutazione finora

- CaseDocumento12 pagineCaseShankar ChaudharyNessuna valutazione finora

- PDF JollibeeDocumento7 paginePDF JollibeeJanwyne NgNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study: Look Before You Leverage: Submitted To: Mr. Johnel Fil T. ArcipeDocumento8 pagineCase Study: Look Before You Leverage: Submitted To: Mr. Johnel Fil T. ArcipeWelshfyn ConstantinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Krispy Kreme Case AnalysisDocumento30 pagineKrispy Kreme Case AnalysisWisnu Sentosa WijayaNessuna valutazione finora

- Smbp14 Caseim Section C Case 03Documento5 pagineSmbp14 Caseim Section C Case 03Hum92re100% (1)

- Ansoff-Matrix Final - v1.1Documento20 pagineAnsoff-Matrix Final - v1.1Abinash Biswal100% (1)

- Generoso Pharmaceutical and Chemicals, Inc.: Background of The StudyDocumento7 pagineGeneroso Pharmaceutical and Chemicals, Inc.: Background of The StudyKristine Joy Serquina67% (3)

- Kraft Foods 2009 QSPMDocumento8 pagineKraft Foods 2009 QSPMLevi Lazareno EugenioNessuna valutazione finora

- CocaCola CaseDocumento8 pagineCocaCola CasefjfjfjfjfjgggNessuna valutazione finora

- SWOT Analysis of Pizza HutDocumento3 pagineSWOT Analysis of Pizza HuthilalamirNessuna valutazione finora

- San Miguel Pure Foods CompanyDocumento4 pagineSan Miguel Pure Foods CompanyErica Mae VistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study (Krispy Kreme)Documento25 pagineCase Study (Krispy Kreme)Katlen Valentino100% (1)

- Application - of - Economic - Concepts-Activity - 2 KATRINA AMORE VINARAODocumento7 pagineApplication - of - Economic - Concepts-Activity - 2 KATRINA AMORE VINARAOKatrina Amore VinaraoNessuna valutazione finora

- Group 4 - Final-MktPlanDocumento61 pagineGroup 4 - Final-MktPlanSakurai GoodNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 6 7 8Documento17 pagineChapter 6 7 8Renée Kristen CortezNessuna valutazione finora

- Analysis of Home Depot's Financial Performance:: Current RatioDocumento4 pagineAnalysis of Home Depot's Financial Performance:: Current RatioDikshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Krispy Kreme Case StudyDocumento4 pagineKrispy Kreme Case StudyBilal RajaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tpccaseanalysisver04 130720110742 Phpapp01Documento17 pagineTpccaseanalysisver04 130720110742 Phpapp01yis_loveNessuna valutazione finora

- Krispy KremeDocumento7 pagineKrispy Kremeblackb99000% (1)

- Goya Helps Latinos Maintain Mealtime Traditions-SentencesDocumento4 pagineGoya Helps Latinos Maintain Mealtime Traditions-SentencespatrickdiemNessuna valutazione finora

- Amy's Bread Case Study: Business and ManagementDocumento3 pagineAmy's Bread Case Study: Business and ManagementMichelle MoraNessuna valutazione finora

- Krispy Kreme Doughnuts 10am To 1130am 1Documento51 pagineKrispy Kreme Doughnuts 10am To 1130am 1beeeeee100% (1)

- Paper Krispy KremeDocumento31 paginePaper Krispy KremeIrving Feiser Pasaribu50% (2)

- Krispy Kreme DoughnutsDocumento31 pagineKrispy Kreme DoughnutsAnkit MishraNessuna valutazione finora

- Krispy Kreme Doughnuts, Inc. A Case Study: By: Wayne ParkerDocumento10 pagineKrispy Kreme Doughnuts, Inc. A Case Study: By: Wayne ParkerAnonymous nj3pIshNessuna valutazione finora

- Krispy Kreme Case Study - ReymarrHijaraDocumento10 pagineKrispy Kreme Case Study - ReymarrHijaraReymarr HijaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Ch05 TB Hoggetta8eDocumento18 pagineCh05 TB Hoggetta8eAlex Schuldiner100% (2)

- The Karnataka Village Offices Abolition Act, 1961Documento12 pagineThe Karnataka Village Offices Abolition Act, 1961Sridhara babu. N - ಶ್ರೀಧರ ಬಾಬು. ಎನ್Nessuna valutazione finora

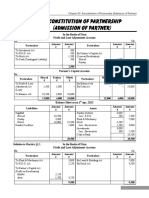

- 03 Reconstitution of Partnership Admission of Partner PDFDocumento24 pagine03 Reconstitution of Partnership Admission of Partner PDFBrawler Stars100% (3)

- Real Estate Investment AnalysisDocumento26 pagineReal Estate Investment AnalysisRenold DarmasyahNessuna valutazione finora

- The Development and Financing of Future FLNG ProjectsDocumento12 pagineThe Development and Financing of Future FLNG ProjectsDaniel Ismail100% (1)

- Concept, Nature and Scope of BankingDocumento33 pagineConcept, Nature and Scope of BankingVasu BhushanNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 3 SolutionsDocumento2 pagineChapter 3 SolutionsMr. FoxNessuna valutazione finora

- Standard Fidic IV Copa For Pwd-Nhai Jobs in IndiaDocumento57 pagineStandard Fidic IV Copa For Pwd-Nhai Jobs in Indialittledragon0110100% (2)

- 5-Year Strategic PlanDocumento53 pagine5-Year Strategic PlanGere TassewNessuna valutazione finora

- Constructive TrustDocumento22 pagineConstructive TrustLIA170033 STUDENTNessuna valutazione finora

- Fortune Motors Vs CADocumento3 pagineFortune Motors Vs CANikki Rose Laraga AgeroNessuna valutazione finora

- Acquisition Ppt1Documento68 pagineAcquisition Ppt1koelpuriNessuna valutazione finora

- Amandeep Singh (6384)Documento10 pagineAmandeep Singh (6384)john_muellorNessuna valutazione finora

- Asset Builders Corporation V Stronghold Insurance Company G.R. No. 187116Documento11 pagineAsset Builders Corporation V Stronghold Insurance Company G.R. No. 187116Rhenfacel ManlegroNessuna valutazione finora

- List of APIsDocumento8 pagineList of APIsSomeshKaashyapNessuna valutazione finora

- Accounting TheoryDocumento192 pagineAccounting TheoryABDULLAH MOHAMMEDNessuna valutazione finora

- Currency Trading - How To Access and Trade The World's Biggest MarketDocumento315 pagineCurrency Trading - How To Access and Trade The World's Biggest MarketSaleel Mohammed100% (4)

- Moral Neutralization in Pakistan Capital MarketsDocumento41 pagineMoral Neutralization in Pakistan Capital MarketsShahab ShafiNessuna valutazione finora

- Capital Market 2Documento25 pagineCapital Market 2manyasinghNessuna valutazione finora

- State Land Investment Corp. vs. CIR, 542 SCRA 115Documento5 pagineState Land Investment Corp. vs. CIR, 542 SCRA 115Mary Louisse Rulona100% (1)

- Tyco ServiceDocumento2 pagineTyco ServiceAnonymous vcadX45TD7Nessuna valutazione finora

- State VA BenefitsDocumento52 pagineState VA BenefitsEd BallNessuna valutazione finora

- Oman Foreign Capital Investment LawDocumento8 pagineOman Foreign Capital Investment LawShishir Kumar SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- (Referred To in Paragraphs 10.2.20 and 10.2.22) : Indenture For Secured AdvancesDocumento3 pagine(Referred To in Paragraphs 10.2.20 and 10.2.22) : Indenture For Secured AdvanceschanderpawaNessuna valutazione finora

- Negotiable Instruments ReviewerDocumento18 pagineNegotiable Instruments ReviewerRowena Yang90% (21)

- 3rd Sem Finance True and False - pdf112958630Documento28 pagine3rd Sem Finance True and False - pdf112958630Lee So Min100% (2)

- Contract DBFODocumento4 pagineContract DBFOJan BooysenNessuna valutazione finora

- Study of Customer Satisfaction For The Loan Product Avaqilable at IIFLDocumento70 pagineStudy of Customer Satisfaction For The Loan Product Avaqilable at IIFLDanya JainNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter Five :agricultural FinanceDocumento42 pagineChapter Five :agricultural FinanceHaile Girma100% (1)

- DBP V COADocumento4 pagineDBP V COARojan PaduaNessuna valutazione finora