Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

The Multinational Corporation and Global Governance Modelling Public Policy Networks

Caricato da

Neil MorrisonDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The Multinational Corporation and Global Governance Modelling Public Policy Networks

Caricato da

Neil MorrisonCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Journal of Business Ethics (2007) 71:321334 DOI 10.

1007/s10551-006-9141-2

Springer 2006

The Multinational Corporation and Global Governance: Modelling Global Public Policy Networks

David Antony Detomasi

ABSTRACT. Globalization has increased the economic power of the multinational corporation (MNC), engendering calls for greater corporate social responsibility (CSR) from these companies. However, the current mechanisms of global governance are inadequate to codify and enforce recognized CSR standards. One method by which companies can impact positively on global governance is through the mechanism of Global Public Policy Networks (GPPN). These networks build on the individual strength of MNCs, domestic governments, and non-governmental organizations to create expected standards of behaviour in such areas as labour rights, environmental standards, and working conditions. This article models GPPN in the issue area of CSR. The potential benefits of GPPN include better overall coordination among industry and government in establishing what social expectations the modern MNC will be expected to fill. KEY WORDS: corporate social responsibility, global public policy network (GPPN), governance, non-governmental organizations, activism ABBREVIATIONS: GPPN Global Public Policy Networks; FDI Foreign Direct Investment; IMF International Monetary Fund; NGO Non-governmental organization; WTO World Trade Organization

Introduction Who governs? This deceptively simple question posed by Robert Dahl about the politics of municipal governance proved complex and controversial enough to require over 300 pages to answer (Dahl, 1961). He

David Detomasi is an assistant professor of international business at the School of Business, Queens University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada. His research areas include corporate governance, corporate social responsibility, and business and society.

would have needed more had he been writing about the unwieldy workings of the modern international economy, whose governance structure is at best uid and at worst non-existent. Normally, the term governance is associated with the institutions of national government, but that association does not hold for issues or activities that transcend national borders. A diverse group of actors today vie with national governments for the right to exert power and authority within that system (Rosenau, 1997). Of these, the modern multinational corporation (MNC) is perhaps the most powerful. Such companies whose production networks may span dozens of countries and involve billions of dollars of assets have not surprisingly taken a keen interest in not only deciphering, but also in shaping, the rules of the global game (Dam, 2001). The rise of private authority mechanisms within the global economy, already well documented by political scientists (Cutler et al., 1999), is but one symptom of the evolving conceptual contours of who can and should govern the international economy. The purpose of this article is to provide an analytic framework for understanding how companies can ethically and legitimately contribute to the governance of the global economy. The model employed is that of Global Public Policy Networks (GPPN), in which the strengths of state, market, and civil society actors combine to create an effective international governance system that overcomes the weaknesses aficting each individually. It proceeds as follows. First, it traces the recent evolution of the MNC as a political and social, as well as an economic, institution. Second, it demonstrates that as the economic power of the MNC expands, so too has public expectation that MNCs contribute to eradicating the social and political upheaval their activity has

322

David Antony Detomasi munist regimes adopted free-enterprise systems almost overnight; rapidly dropping trade barriers and clamouring for more investment in order to improve their competitiveness. As the benets of foreign direct investment (FDI) began to accumulate, the market for it became extremely competitive. Consequently, many states scrambled to dismantle the barriers they had put in place to regulate investment activity. Liberalizing bilateral and multilateral investment and trade agreements proliferated; and many governments created investment promotion programs designed to highlight their internal advantages to potential MNC investors. Internally, governments amended regulatory impediments to investment, implemented tax breaks and holidays, extended tax credits for research and development expenditures, and often provided government subsidies to investing rms. All these measures were designed to make individual countries more attractive to increasingly discriminating foreign investors. Improvements in information technology augmented MNCs investment freedom. Enhanced information management capacities allowed rms to restructure operations to maximize efciencies in global production and distribution capacity, to coordinate an extensive global supply chain across dozens of countries, and to improve individual plant productivity. MNCs also used information technology to develop new governance structures that relied less on pure markets or hierarchies and more upon a disparate but technologically connected network of strategic alliances, partnerships, and cooperative arrangements. Production processes became uid, global, and increasingly divorced from the regulatory control of any individual nation-state (Kobrin, 1997). Technology and increased investment freedom gave MNCs signicant bargaining leverage in their relationships with host governments. Consequently, over the past 15 years, the amount of foreign direct investment, foreign sales, foreign afliates, and foreigners employed by MNCs exploded (United Nations, 2004). Today, large MNCs by some measures rival all but the most developed countries in terms of economic output.1 Yet the picture has not been all rosy. Companies could no longer rely on protected domestic markets for predictable returns as foreign competitors began to compete for domestic customers. They raced to build production and distribution capacities in new markets, fearing loss of

contributed to. Third, we develop criteria that an effective international governance systems needs to possess, and demonstrate that no individual actor possesses all such criteria. Fourth, we outline a model by which GPPN can overcome these individual weaknesses. Finally, we demonstrate how GPPN are actually working in practice, sketching the contours of a global governance research agenda that other scholars might wish to take up.

Globalization and the multinational corporation In the domestic environment, national governments are tasked with providing transparent, robust, and effective regulatory systems that underpin the market mechanism, and they do this job more or less well, depending on their ideology, internal capabilities, accumulated experience, and domestic economic resources. This tasking, however, is difcult to replicate at the international level. The structural condition of anarchy in which no international authority exists that can perform the legislative, executive, and judicial functions of equivalent state institutions prevents such a clear allocation of regulatory responsibility. This lack of clarity constrains what (if any) rules can be written and how effective those rules will be in constraining what actors do. MNCs have of course understood this for a long time. During the Cold War, most MNCs focused their political strategies on inuencing home and host governments (Gilpin, 1975). MNCs often attempted to inuence the trade and industrial policies of their home governments in order to enhance their competitive position (Dam, 2001; Milner and Yofe, 1989), and coped with import substitution policies, heavy unionization, and the signicant political risks associated with operating in developing markets or nominally Communist regimes (Brewer, 1985; Stapenhurst, 1992). Not surprisingly, companies became good at anticipating national political demands and eventually began to view the capacity to inuence public policy within multiple jurisdictions as a competitive business skill (Prahalad and Doz, 1987). The end of the Cold War signicantly altered both how and how much international business companies could do. New global markets increased the demand for consumer goods. Formerly Com-

Multinational Corporation and Global Governance market share to more aggressive competitors. The capital market globalized as well: investors scoured the world for the best investment opportunities, and shareholders pressed public companies to show superior returns each and every quarter. Size and global reach appeared to increasingly matter: merger and acquisition activity rose dramatically. All this pressured company executives to wring ever-greater performance out of their streamlined global production network. Those charged with managing that network could have borrowed from Winston Churchill in noting that the blessings of globalization were quite effectively disguised. If globalization increased the bargaining clout of MNCs vis a vis national governments, increased global competition compelled them to use that clout. Companies bargained hard for improved investment conditions, and searched the globe for production facilities that could minimize costs. The results were predictable. For production processes that required quantities of unskilled or semi-skilled labour, companies evaluated investment sites whose overall operating costs measured in wages or regulatory demands were low. This phenomenon, technically termed regulatory arbitrage, was disparaged as an MNC-induced race to the bottom in which developing nations competed in regulatory laxity as their primary basis for drawing FDI. On the international front, companies whose economic return depended upon the protection of intellectual capital pressed hard for national and international recognition of stringent intellectual property protection. International success also required the capacity to repatriate earned prots: consequently, companies pressed countries to liberalize capital controls, leaving them vulnerable to nancial crises. Signicant market logic underpinned the demands MNCs placed on domestic and international regulatory regimes. That market logic provoked critics who noted the signicant social costs such practices engendered and increasingly demanded that measures be taken to mitigate them. Initially, such groups targeted their criticism at international economic organizations such as the World Trade Organization (WTO), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Bank claiming that they had neither regulated the pace at which globalization occurred nor moderated the damage that it caused. In fact, they accused these

323

organizations of endorsing policies that augmented rather than dispelled such damage, and protests at the international meetings of these organizations became, and are now, an expected rather than a surprising occurrence. Activists, however, did not stop there. They also began targeting individual companies as well, criticizing them for tolerating, even promoting, unacceptably low wage and environmental standards in their global network. Activists created formidable public protest campaigns that featured organized consumer boycotts, media campaigns, and staged protests, all designed to highlight egregious examples of poor corporate behaviour, raise popular outrage, and alter consumer spending patterns. This helped forge a powerful public consensus that companies could and should contribute more to the sustainability of an economic system from which they drew signicant benet. Of course, none of this was particularly new: MNCs had for decades confronted engaged activists demanding better social responsibility. The basic criticisms have remained consistent: critics argue that the growth of the MNC and the dispersion of stock ownership has in effect made the MNC accountable to no one: that the transparency of company operations particularly those occurring in remote or developing areas remains poor and needs improvement: that international regulatory mechanisms over such areas as taxation, articles of incorporation, and transfer pricing were underdeveloped; and that stakeholder considerations require greater prominence in corporate decision-making. What has changed is the content of the remedies proposed. Rather than relying on the instruments of public regulation via overt government institutional oversight or even the appointment of public representatives to company boards of directors greater expectation of public responsibility today is placed upon companies themselves. In previous eras, that antidote to corporate excess was state regulatory activity; today, few argue for the return of the regulatory assertive state, which would inevitably raise public expenditure and could potentially divert investment. Today, greater governance responsibility is placed on companies themselves. Many companies have taken the hint. An indication that MNCs increasingly accept broader stakeholder obligation is the current emphasis

324

David Antony Detomasi those who are subject to that authority. Second is accountability for decisions taken; that mechanisms exist whereby those who exercise power are periodically called to account for the consequences of what they do. The third function is capacity that the institutions entrusted with the governance function possesses the resources, administrative capacity, and specialized technical knowledge necessary to exercise governance effectively. Finally, effective governance requires enforcement: that those transgressing established rules face at least normative, if not punitive, damages. Domestically, the act of governance is exercised by the legislative, judicial, and executive institutions of a national government. In democracies, consent of the governed via periodic elections establishes the legitimacy for individual governments to wield authority; such governments create laws and domestic regulatory institutions that become the instruments through which authority is exercised. However, the domestic model is less than helpful in the international realm, which lacks a centralized supranational political authority that provides the equivalent functions of a domestic government. But that does not mean governance in the international system is absent. On the contrary, a great deal of governance is exercised internationally: for example, existing technical standards manage international transport and communication procedures, and states have created and ratied international treaties that cover issues ranging from trade to arms control to human rights. Despite often weak enforcement or punitive capacities, most rules are followed by most states most of the time; indicating that they normally accord them sufcient legitimacy to want to avoid violating them. An international governance system in the issuearea of CSR would require building all of the foundational elements of capacity, legitimacy, accountability, and enforcement. This section argues that the structure of such a system would need to reect the interests and inputs of the various actors noted in the previous section, because no one actor is individually capable of providing these elements by itself. Figure 1 details the various actors and institutions that help shape the norms and practices of corporate social responsibility in an international context, and provides an outline of their individual governance capacities.

many of them place on developing or renewing their public commitment to the broad domain of corporate social responsibility (CSR). Developing new or extending existing internal company policies related to the companys social performance indicates a commitment that goes beyond simply meeting extant legal requirements in individual jurisdictions. While these efforts might be dismissed as merely an exercise in public relations, there is increasing evidence that stakeholder management is an important component of competitive advantage. Done properly, such commitments can provide rms with greater insight into local markets, lowers their media, social, and political risk, enhances the quality of the workforce, and attracts new recruits. To summarize, the growing economic power of MNCs poses signicant challenges to the existing institutions nominally charged with governing their activity. Activists have highlighted the social inadequacies of unregulated global production processes, and have demanded greater social performance from companies themselves. In response, many companies have crafted CSR policies designed to address the social impacts of their production practices. Yet there remains considerable discrepancy in the degree to which various companies endorse CSR, and activists remain suspicious that the avowed commitment to CSR will result in any clear change in MNC behaviour. In short, managing the social responsibilities of MNCs remains a gap in the current global governance system, one in which many actors vie for inuence. The following section details the specic capacities, strengths, and weaknesses of those actors in the issue area of CSR, setting the stage for the discussion of GPPN that follows.

Global governance and corporate social responsibility The act of governance involves setting the rules for the exercise of power and for determining who can legitimately wield that power. Effective governance systems possess certain characteristics. The rst is legitimacy; that the agents exerting governance authority possess the acknowledged right to do so by

Multinational Corporation and Global Governance

Private Governance Actors

Multinational Corporations/Industry Associations Strengths Technical Capacity Economic Resources Internal Control Mechanisms Motivation Weaknesses Legitimacy Experience/Knowledge Collective Action

325

Public International Institutions

Strengths Institutional Strength Possibility of Sanctions Articulated mandate Weaknesses Domestic Legitimacy Limited Issue Focus

Activist and Civil-Society Groups

Strengths Awareness Building Issue Specific and Local Knowledge Weaknesses Legitimacy Limited Issue Focus

National Governments

Strengths Legitimacy Enforcement capacity Domestic Institutional Capacity Weaknesses Need to cultivate FDI Corruption or capture of officials

Figure 1. Global governance and corporate social responsibility participating actors.

Starting from the top left, private sector actors, such as MNCs, international industry associations, and professional standardization and ratings agencies, do exert international governance authority via several mechanisms (Cutler et al., 1999). Private actors possess several key governance strengths. The rst of these is competence and capacity. Firms are experienced in creating governance systems that lower transaction costs and which provide inducements and penalties to structure how managers make decisions. They have an economic interest in establishing effective international governance mechanisms that reduce transaction costs, lowering operating risks, and ensure replicability, predictability, and transparency in international business dealings. Moreover, rms and industry associations may possess specialized knowledge and expertize in individual issue areas that state institutions may lack; consequently their authority is either given legitimacy by governments or legitimacy is acquired through the special expertize or historical role of the private sector participants. (Ibid; 5). Examples of such private-sector governance activity include trade and industry associations that promote common standards in specic industries and can act as an international advocate for regulatory convergence in those industries (Brathwaite and Drahos, 2000). Industry associations can work to shape both a governments domestic policy and bargaining positions in international trade disputes. Other examples include resource-intensive industries, in which multinational rms may operate cartel

arrangements to protably manage the ow of output (Spar, 1994). Private regulatory agents such as bond rating agencies (Sinclair, 2005) or accounting regulators also can exert powerful governance authority over the companies that operate in their issue areas of expertize. The production networks of individual multinational corporations themselves are an impressive feat of international governance. Product rms often feature not only vertically integrated production structures that may employ tens of thousands of people, but they have also integrated a dense network of associated rms that are loosely coordinated through varied ownership structures and assigned production tasks. Professional service rms operating in such elds as insurance, law, accounting, and consultancy also exert mechanisms of governance that shape the practice of their profession internationally. These rms coordinate their service activities across borders and their internal processes often provide models for the appropriate internal governance of such systems. Individual companies themselves can exert signicant internal acts of governance, and private agents can exert considerable authority due to their knowledge assets, global reach, and collective political weight. Private agents, however, also lack other required characteristics of an effective international governance system. The most obvious is broadly accepted legitimacy to exert governance in social, as well as economic, realms. Legitimacy has several different interpretations for rms. To be sure, managers have

326

David Antony Detomasi pate in the global governance of CSR, their participation alone would be insufcient. Public international institutions can also exert governance in specic issues areas related to CSR. The dening characteristics of public international institutions is that they are charged with policy development and implementation in clearly dened areas and that they draw their legitimacy and support from their members, which are exclusively nationstates. The most prominent examples of such institutions include the World Trade Organization, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank. Advantage they possess over private institutions is their legitimacy and institutional capacity. Legitimacy they derive from their members, which are national governments, who in theory can be expected to endorse negotiated agreements, implement created policies, and administer approved sanctions. These institutions also posses the additional advantage of institutional capacity. Sustained effort by the leaders of powerful states led to their creation: these leaders believed that such institutions would serve both their individual and the worlds collective interests by fostering peaceful political and economic relations between states and progressive economic development within them. They have largely succeeded in their original mandates: the 50-year pursuit of market liberalization in the area of trade and nancial liberalization-pursued via the tumultuous negotiating rounds of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and via the IMFs liberalization and stabilization policies is a case in point. Such institutions have provided such key functions as providing forums for negotiation and mechanisms to administer agreements: the vast increase in international economic activity noted earlier testies to their success. Today, while admittedly having achieved some degree of independence, such institutions continue to draw legitimacy, funding, and mandate from delegates of nation-states. This means that they suffer two specic limitations on what they can and cannot do. First, such organizations concern themselves primarily with addressing those problems that state governments feel are important. Consequently, they often do not possess mechanisms by which non-state actors can participate in their deliberations. Consequently, non-state actors who often wield significant power and inuence nd that their interests

long acknowledged that a company is a social as well as an economic institution: its continued existence depends upon a social willingness to grant incorporation rights; and responsible exercise of that privilege is a pre-requisite for maintaining social support of the corporate form. However, the weight given to this economic imperative conditions the activities of private actors and raises suspicions of their ultimate commitment to CSR activity. Critics point out that organizations created primarily if not solely to service economic ends cannot also be neutral contributors or purveyors of public goods (Wartick and Cochrane, 1985; Wood, 1991). Private actors inevitably face conicts of interest: prot and shareholder motives raise the temptation for companies to inuence international and domestic governance mechanisms with an eye to creating competitive advantage. This, critics point out, companies already do well: their specialized knowledge inuences what policies their governments promote in contentious areas of international commerce such as intellectual property protection or anti-competitive trade practices. Put bluntly, any form of regulation that companies must meet will inevitably raise costs, and companies cannot be expected to both minimize production costs and also endorse governance mechanisms that might raise those costs. Critics also point out other factors that limit the governance capacities of private actors, also outlined in the Figure 1. First, effective mechanisms for review and potential censure of how companies pursue CSR are rudimentary. While shareholders can and occasionally do demand improved social performance: they are primarily interested in economic gain, and can often exercise disapproval by exit rather than voice. Second, private actors may not possess the requisite knowledge or skills to perform the specically public functions of governance. Third, companies suffer from collective action problems in managing CSR efforts: they are often unwilling to incur the extra costs such measures entail unless they are assured that competitors will bear the same burdens. Lack of legitimacy, accountability, specic public sector knowledge, and collective action problems limit the ability of private actors to develop a global CSR governance system. While certainly such actors would need to partici-

Multinational Corporation and Global Governance or goals are not always adequately served by existing international institutions, resulting in their increasing alienation from the global governance process. To be sure, while both the IMF and WTO have made efforts to become more inclusive of non-state actors within their deliberation process, their dependency on state endorsement ultimately constrains that accommodation. Second, their success at fostering economic liberalization has also led to calls for them to expand their mandate to ameliorate the social ills created economic liberalization. Pressures placed upon the WTO to use trade policy to induce domestic governments to create strong regulatory measures to protect intellectual property and enhance labour and environmental standardsthe socalled trade and ... agendaare cases in point. Despite nominal responsibility for formulating international labour standards is ascribed to the International Labour Organization (ILO), pressure is often placed on the WTO to adopt social standards because they possess the potential punitive measure of trade policy sanctions. This pressure has often been resisted by the WTO, whose ofcial profess wariness of expanding their organizational prerogative beyond circumscribed bounds and scepticism that trade or nancial liberalization policies can by themselves induce governments to enact the regulatory policies that emulate those possessed by more developed nations. Instead, they advocate that the responsibility to provide public goods related to environmental, health, or labour standards resides primarily with national governments. Yet pressures to widen their mandate continue to be voiced. International public institutions often score better on the legitimacy and accountability variables than do their private counterparts. Their mandate, derived from nation states, provides those advantages, but it also creates clear weaknesses. Their focus often remains the interests of nation-states, to the detriment of non-state actors. They do not possess direct institutional strengths in addressing the key issues that concern the topic of CSR; they only possess peripheral strengths at addressing these concerns via the mechanisms of trade and investment policy. In short, while possessing a defensible claim to be able to act in the public interest, there are strict limits to how much they can realistically do.

327

A third group of actors that demand input into the CSR debate are civil-society and activist groups discussed earlier. Politically, such groups derive power from the ability to harness and distribute provocative information that results in public outcry. Presumably such public outrage has a real impact on what individuals buy and perhaps even how they vote. Activists unite individuals residing in different countries around a common theme that they believe demands more attention than elected ofcials or corporate executives currently pay it. Their power to inuence formal governance channels both public and private is considerable, and they have achieved notable recent successes in highlighting the negative effects of globalization and forcing corporate executives to respond to it. The public outcry of Nikes use of contracted footwear companies whose working conditions were abysmal, or Greenpeaces success at inducing public outrage over Royal Dutch Shells proposal to dispose of an oil rig in the North Sea, are well-known popular examples. Activists, governments and companies have learned, should not be underestimated. For activists, the emphasis on specic issue(s) that provides the necessary focus to recruit new members and inuence public policy is a source of strength. Focus creates vision, which can motivate new members to join and existing members to exert considerable effort in the name of the organizations goals. Such efforts also provide the necessary social momentum that translates into political inuence. However, this focus also generates weakness. First and foremost, activist groups engender concerns about accountability: their mandate is drawn from a self-selected constituency that makes no claim to be representative of a broader national constituency. Moreover, the focus on progress across a limited number of select issues means that their demands on companies and governments are often unrealistically high. The reliance on aggressive media strategies as a tool to inuence public opinion may preclude the patience required to advance interests within more institutionalized forums. These factors limit the capacity of activist groups to play an independent role in setting CSR expectations. A nal actor that requires participation in the CSR global governance process includes individual nation-states. The social performance expected of MNCs goes to the regulatory heart of the modern

328

David Antony Detomasi possessed by industry actors, and the legitimacy garnered by state regulatory endorsement. They occupy the indeterminate zone between formal institutions of domestic and interstate law and the realm of anarchy. They are symptomatic of an associated concept of governance through networks in which interested parties, both state and non-state, combine their specic strengths to establish procedural and expected norms that condition their mutual activity (Slaughter, 2004). Effective global governance of MNC activities demands the combinations of strengths evinced by these various actors. GPPN are one potential model that such a system might employ. Figure 2 demonstrates how GPPN might be understood in terms of the emerging global governance area of CSR. The top level of the Figure 2 indicates policy inputs from various actors, each of whom has clear interest in participating in such networks. For MNCs, GPPN provide a mechanism for dialog and for input into the CSR expectations that they will be expected to fulll. Such companies have an interest in clarifying such standards and in ensuring that they apply to as many competitors as possible. This will help each individual MNC overcome collective action concerns, will adding predictability and consistency into the international operating environment, and will provide a base reference for understanding what they can and cannot be reasonably expected to fulll in the area of CSR. States are a second element of knowledge input into GPPN. GPPN allow states to choose a third course between abandoning regulatory control in order to encourage investment and aggressively asserting such control to the point of deterring investment and hurting overall economic development. Participating in a GPPN networks also helps states overcome collective action problems associated with the race-to-the-bottom literature; common standards across countries and industries can enhance clarity and transparency for both states and rms. In addition, GPPN are also attractive for national regulatory agencies. They help provide specic exchanges of ideas, information, and expertize in CSR related areas while posing little threat to the broad domestic mandates that many regulatory agencies have worked hard to construct. GPPN can serve the broader mandates of governance that preserve the core elements of sovereignty while also

nation-state. Not surprisingly, each country would want to retain ultimate prerogative over what labour, environmental, and wage standards it chooses to endorse. States, particularly democratic ones, possess the strongest claims to legitimacy among the interested actors, and typically also possess the strongest institutional capacities for the domestic enforcement of expected standards. However, as previously noted the economic pressures of globalization may tempt states to lower regulatory standards or to run the risk of high regulations deterring foreign direct investment. While states would want to help shape international expected standards in the area of CSR, any successful process would need to ameliorate this competitive pressure and provide states with increased bargaining leverage in terms of what they could realistically expect from investing rms. To summarize, the governance challenges posed in the era of globalization are signicant in the issue area of CSR. Various actors currently contribute to the ongoing effort to establish clear expectations of the social obligations of multinational corporations. Each possesses strengths and weaknesses; none can by itself claim the mantra of governance provider in the area of CSR. Filling this gap requires a different governance structure and approach. The following section outlines a model of one potential governance solution, in which Global Public Policy Networks (GPPN) act as a potential source of effective international governance in the area of CSR. Governance through global public policy networks In order to address this governance gap, alternate models of global governance have been developed that are designed to overcome the need for effective regulation in an age of diminished state capacity and economic globalization. One such option lies in governance through Global Public Policy Networks (GPPN). GPPN feature collaborate efforts by various actors designed to address common problems. Their particular strengths lie in their ability to integrate public, private, and non-governmental efforts in managing the governance challenges posed by particular policy areas (Reinicke, 1998). Their particular strength is inclusiveness: they operate by bridging the technical and administrative expertize

Multinational Corporation and Global Governance

329

Multinational Corporations

National Governments

Activist/ Civil Society Groups

Micro GPPN

CGIAR CAVI WCD

GLOBAL PUBLIC POLICY NETWORKS

Macro GPPN

The Global Compact

Codified Standards of Expected Performance

Enforcement Mechanisms

Ongoing Evaluation and Review

Figure 2. GPPN in terms of the emerging global governance area of CSR.

allocating requisite authority to those best placed to wield it. Activists and NGO groups also see benets from participating in GPPN. First, participation in such networks solidies their impact on corporate planning over the long term. Aggressive media strategies entail risk: they may or may not attract the necessary broad public interest necessary to motivate change, and they are expensive and difcult to maintain over time. Great long-term effect may be generated by working with companies to create higher labour and environmental standards. Some NGOs already participate in the investment planning process, and some MNCs are actively cultivating their participation. Undoubtedly some of this is simply media risk management; however, to companies activist and NGO groups are often a vital source of local knowledge of host states that companies need to access (Prahalad, 2005). Activists participate in GPPN because over time such networks offer the strongest capacity to play an ongoing role in the decisions that companies make. The second level of the model involves the activities of GPPN themselves. Their function remains primarily institutional. First, they provide an institutionalized forum for dialogue and debate. GPPN provide mechanisms for inclusive discus-

sions in which the various actors can participate directly. Second, they act as a repository of information. First, GPPN can codify decisions and agreements taken, allowing each participating group to review the agreements before choosing to endorse them. This adds legitimacy to the decisions reached because they have been endorsed by the very actors expected to implement them. Finally, GPPN act as a reference and dispute resolution body. First, new members wishing to join a given GPPN would likely need considerable guidance in terms of norms and expectations of procedures. Second, as disputes about implementation and interpretation are bound to arise, GPPN can provide mechanisms to resolve disputes in an ordered and predictable fashion. The third level of the model represents the policy outputs that GPPN create. The rst and most obvious role is standard setting, in codifying the expectations around general issue areas. In the case of CSR, this includes clear expectations in the primary areas of labour, environmental, and wage standards. A second policy output includes enforce ment mechanisms. These range from possible groups sanctioning of transgressors to outright expulsion form the GPPN, an action which would inict signicant normative costs on the specic actor.

330

David Antony Detomasi and Other Business Enterprises with Regard to Human Rights is explicit in this regard. In the case of the rights of workers, for example, this document states that transnational corporations shall ensure the freedom of association and effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining by protecting the right to establish and ... to join organizations of their own choosing. Rather than noting how such an explicit statement may appear to infringe on legitimate state prerogative, the document also argues that companies should perform such functions within their respective spheres of activity and inuence. (United Nations, 2003). Under this document, the burden of governance responsibility is passed to those best able to perform it, which may be the company itself. International institutions have also been active in promoting improved CSR in partnership with companies, activists, and state governments. For example, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), which grew out of a joint initiative between the U.S. Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies(CERES) and the United Nations Environment Programme. The GRI was and is designed to complement existing nancial reporting frameworks with an environmental reporting framework that provides guidance for companies in reporting on the environmental sustainability of its current operations. Both of these adopted codes involved consultation with industry and government groups in their formulation. They are and were issue-specic, designed to improve reporting requirements in the areas of environmental impact assessment and reporting. These individual efforts have laid the foundation for larger GPPN to form in the area of CSR. Today, several prominent examples of these networks exist. The most visible GPPN in this area is the United Nations Global Compact initiative, a program introduced by U.N. Secretary General Ko Annan at the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in 1999. The Global Compact is designed to engage multinational corporations in addressing the broader issues of systemic underdevelopment, and calls on business leaders to work with governmental and non-governmental agencies to further the cause of sustainable globalization. Initially designed to foster greater cooperation between the UNs development efforts and the activities of multinational

A third output of effective GPPN would be an ongoing evaluation of its effectiveness as a governance organization, so that it can anticipate and react to new governance challenges and identity areas in which its current performance is inadequate. GPPN in the area of CSR are beginning to emerge. One foundation for GPPN has been the surging number of codes of conduct, issued by various bodies, designed to clarify expectations of MNC activity is CSR areas. Prime examples of this include the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)s Guideline on Multinational Corporate Behaviour, originally published in 1976 and revised ve times since, with the most recent review culminating in June 2000. The text of the most recent version, entitled Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, reinforces the economic, social, and environmental components of the sustainable development agenda. It is complement by other well-known codes as the Global Reporting Initiatives reporting requirements and the Sullivan principles, originally created to help condition MNC activity in an apartheid South Africa. These are but several of the more well-known efforts: they are complemented by many other codes of corporate conduct issued by various organizations. Efforts are on for the creation of codes of expected corporate conduct, which has united several themes. All acknowledge that they do not carry the full weight of domestic law, that MNCs choose to endorse them or not, and that sovereign governments ultimately decide whether and how to enforce them. However, that does not render them powerless. First, their effectiveness lies is their capacity to establishing norms of expected behaviour that inuence the patterns of domestic law enacted by national governments. Second, there wording is specic enough to be clear but also exible enough to allow states and rms to choose particular routes and methods of implementation. Third, especially so in the case of the OECD, their endorsement by reputable international organizations to which states belong make them difcult to ignore. Such codes have been augmented by increasing efforts by intergovernmental organizations to create additional written expectations of MNC conduct that go beyond individual domestic legislation. The language of the United Nations Draft Norms on the Responsibilities of Transnational Corporations

Multinational Corporation and Global Governance corporations in the developing world, the Global Compact has achieved a high degree of corporate participation and endorsement from a wide variety of actors. The Global Compact has issued nine principles that were derived in consultation of established UN documents and other established international organizations. They are designed to represent commitments to achieving basic principles in the areas of human rights, labour, and environmental legislation. More specic examples of GPPN working in action include the following. The Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) supports agricultural research centres located primarily in the developing world. This informal association involves public and private sector members dedicated to enhancing food security and contributing to poverty eradication. A second example is the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI). Launched in early 2000 at the World Economic Forum, this organization harnesses public and private resources to increase support for immunizations activities, focusing primarily on providing equal access to vaccines. Finally, the World Commission on Dams (WCD), convened in 1997, produced recommendations and demonstrable action by public, private, and civil society organizations in order to enhance the sustainability of dam projects in the developing world. All of these initiatives combined the individual strengths of the private, public, and civic sector in order to enhance the provision of global public goods (Nelson, 2002). These examples indicate that GPPN are indeed forming in the realm of CSR. They often possess technical, administrative, and economic resources that exceed those available to host states, and draw on the various capacities of interested actors in order to develop their governance capacities. These networks utilize the individual strengths of the various actors involved to overcome their individual weaknesses. One of them is organizational form: such networks involve extensive use public/private partnerships, and other forms of cooperative arrangements between the public and private spheres to help implement agreed plans. Rather than replacing or by-passing the established state governance apparatus, these networks are designed to complement that apparatus with the particular strengths of the NGO and private sector. The common element to the

331

GPPN models is the tacit admission that states no longer monopolize the act of governance but instead rely upon the specic skills, knowledge base, and technical capacity of other agents to help them govern. The appearance of GPPN in the area of CSR, and the model proposed to describe their functioning, raises important questions for future researchers. One involves whether GPPN are best constructed on an issue-by-issue basis such as the particularized examples noted above, or whether the broader approach typied by the Global Compact initiative will achieve more effective governance results. The advantages of issue-specicity include the narrowing of expertize and contested policy questions into manageable proportions: the specic problems associated with individual issue-areas may be more manageable than those aficting the macro approach exemplied by the Global Compact. However, if successful, a multilateral macro approach has the advantages of wide endorsement. An analogy with trade negotiations is perhaps helpful here: bilateral, issue-specic trade deals are easier to conclude between two or three individual states, but a broader multilateral trading system, exemplied by the GATT and the WTO, provides broader systemic appeal and can prevent the emergence of regional isolationism. As in trade policy, a key challenge for the study of GPPN in the issue area of CSR is whether broader multilateral efforts involving a wide number of interested actors ultimately works to reinforce or oppose the work of more limited GPPN in individual issue-areas. A second research question involves the validity of the models precepts. Most GPPN are relatively new. The offered model argues that effective GPPN will have built into them mechanisms for ongoing evaluation of their own capacities and function. In this regard, the inclusivenss of GPPN may actually be a weakness. Borrowing from the domestic state analogy, most governance systems have external observers and critics the media, opposing parties, concerned citizens who collectively judge the effectiveness of an individual government activity. However, inclusive governance models may remove the element of external criticism necessary to invigorate a governance process. While this concern may be more conjectured than real none of the GPPN cited here have obtained the full membership

332

David Antony Detomasi adept at using that leverage: globalization has forced rms to raise efciency and adopt cost-minimization strategies that both raise sustainability questions and arouse the ire of the NGO community. A growing number of MNCs acknowledge the need for sustainable production practices, but face considerable practical problems in implementing them. One of those problems is the structure of global business regulation. Built in an era of relative state dominance, current global governance structures do not necessarily give adequate voice to interested non-state actors, and often provide economic disincentives for rms to endorse CSR mechanisms. Both rms and NGOs have contributions to make in the global governance process, current structures do not take full advantage of the individual strength each possesses. GPPN offer one potential framework for overcoming the weaknesses in the current system of global governance. By combining the individual strengths of rms, states, international institutions, and activists, they may succeed collectively what each cannot individually do. This paper has chronicled their emergence in areas related to CSR and has provided a proposed model for analyzing how they work. Certainly more work can be done in both areas, which will undoubtedly aid our understanding of CSR and global governance. Certainly the success of GPPN is not guaranteed. The involved agents may resist further collaborative efforts because they intrude on what they believe their core competency really is. Companies themselves may resist more formal involvement in governance, preferring to maintain an individualized market production strategy coupled with a non-market strategy for choosing how they will respond to the demands placed upon them by NGOs and activist groups. States may think that GPPN weaken rather than augment their sovereign powers and therefore ignore or undermine them. Activists may fear that involvement in GPPN may erase their perceived independence, weakening their power to induce change. All of these are clear issues that effective GPPN would have to overcome. However, there is reason for optimism about why GPPN will receive support from these diverse groups. MNCs participation allows them to legitimately shape the international regulatory environment

or endorsement of all interested actors the rigour with which past decisions are examined will be a necessary component of effective GPPN activity. A third potential question other researchers might undertake is the relative balance of power between the various contesting actors in individual GPPN. The model as presented indicates that governance input into GPPN is shared equally among the actors participating in the network. That clearly will not always be the case. For some issues, states will likely emphasize their legislative prerogatives more stringently than others. In other, the specic capacities of individual NGOs may be more important for example, distribution of needed pharmaceuticals to combat the AIDS epidemic aficting many developing nations often falls to NGOs, who have built the necessary local trust that is a prerequisite to such distribution. It is clear that, within each GPPN, a balance of governing power will emerge over protracted bargaining; whether that balance is an effective one for governing the specic issues will be a topic for further individualized research. This list of potential research questions is by no means exhaustive indeed, it is at best preliminary. Continued examination of this new governance form by interested researchers will test the models validity and will undoubtedly lead to its further amendment and renement. GPPN hold various strengths, including capacity, legitimacy built through inclusiveness, and exibility. They also face stiff opposition from entrenched governance patterns. Investigating this particular strengths and weaknesses will likely yield benets to both scholars and practitioners in the evolving eld of global governance.

Conclusion In an increasingly globalized world, MNCs have gained considerable power. They are used to the existing state-based system of commercial regulation, and there are several reasons why they might wish to maintain it. The advantage of using this system is that the MNCs know the system well, and the system uses effective tools for managing and currently provides them with signicant leverage. They have proved

Multinational Corporation and Global Governance in which they operate. States can reclaim more governance capacity in economic areas, and activists are accorded an accepted role in the formulation of investment conditions and social performance mechanisms. GPPN provide modes by which states, companies, and civil society groups can collaboratively fashion the governance of international economic activity. All of these provide sustainable incentives for GPPN to proliferate. The international system is anarchic that is, it lacks a centralized governing institution that has a recognized executive, legislative, and judicial body (Arend, 1999). However, that does not mean that it is bereft of governance the orderly establishment of rules and regulatory mechanisms that function effectively even though they are not endowed with formal authority. GPPN are one emerging mechanisms by which governance is exercised in the international system. They hold the potential to move the CSR debate away from the standardized arguments of the past and towards a more productive creation of an effective governance system for the social performance of MNCs. They will likely play a key role in the years ahead, one that holds considerable promise for further investigation by interested scholars.

333

Note

Some measures compare the economic assets controlled by the largest corporation with the Gross Domestic Product of countries. According to this measure, the largest MNCs have more economic clout than all but the most developed national economies. However, when measured by the amount of value-added activity that an MNCs actually performs a measure much more similar to that used for calculating GDPtheir economic clout, while remaining signicant, drops off considerable. For a discussion of this measurement issue, see Wolf (2004: 221223).

1

References

Arend, A. C.: 1999, Legal Rules and International Society (Oxford University Press, Oxford). Braithwaite, J. and P. Drahos: 2000, Global Business Regulation (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge).

Brewer, T.,: 1985, Political Risks in International Business: New Directions for Research, Management, and Public Policy (Praeger Publishers, New York, NY). Cutler, C., V. Hauer, & T.Porter, ,: 1999, Private Authority and International Affairs (SUNY Press, Ithaca, NY). Dahl, R.: 1961, Who Governs? (Democracy and Power In An American City Yale University Press, New Haven, CT). Dam, K. W.: 2001, The Rules of the Global Game (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL). Gilpin, R. E.: 1975, U.S. Power and the Multinational Corporation: The Political Economy of Foreign Direct Investment (Basic Books, New York). Kobrin, S. J.: 1997, The Architecture of Globalization: State Sovereignty in a Networked Global Economy, in) J. H.Dunning (ed.) Governments, Globalization, and International Business (Oxford University Press, Oxford). Milner, H. V. and D. B. Yofe: 1989, Between Free Trade and Protectionism: Strategic Trade Policy and a Theory of Corporate Demands, International Organization 43(2), 239272. Nelson, J.: 2002, Building Partnerships: Cooperation Between the United Nations and the Private Sector (United Nations Publications, New York). Prahalad, C. K.: 2005, The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid (Wharton School Publishing, Upper Saddle River, NJ). Prahalad, C. K. and Y. L. Doz: 1987, The Multinational Mission: Balancing Local Demands and Global Vision (The Free Press, New York, NY). Reinicke, W.: 1998, Global Public Policy: Governing Without Government? (Brookings Institution Press, Washington). Rosenau, J. S.: 1997, Along the Domestic-Foreign Frontier: Exploring Governance in a Turbulent World (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge). Sinclair, T. J.: 2005, The New Masters of Capital: American Bond Rating Agencies and the Politics of Creditworthiness (Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY). Slaughter, A. M.: 2004, A New World Order (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NY). Spar, D.: 1994, The Cooperative Edge: The Internal Politics of International Cartels (Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY). Stapenhurst, F.: 1992, Political Risk Analysis Around the North Atlantic (St. Martins Press, New York, NY). United Nations (UN): 2003, Draft Norms on the Responsibilities of Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises with Regard to Human Rights, document number E/CN.4/Sub.2/2003/12. United Nations (UN): 2004, World Investment Report (United Nations Publishers, New York).

334

David Antony Detomasi

David Antony Detomasi School of Business, Queens University, Kingston, ON, Canada E-mail: ddetomasi@business.queensu.ca

Wartick, S. L. and P. L. Cochrane: 1985, The Evolution of the Corporate Social Performance Model, The Academy of Management Review 10(4), 758769. Wood, D. J.: 1991, Corporate Social Performance Revisited, The Academy of Management Review 16(4), 691718.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- 3 Market Integration The Rise of Global CorporationsDocumento45 pagine3 Market Integration The Rise of Global CorporationsPaul fernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- The Impact of Multinational EnterprisesDocumento28 pagineThe Impact of Multinational EnterprisesfalconshaheenNessuna valutazione finora

- GMS724 Learning ObjectivesDocumento59 pagineGMS724 Learning ObjectivesZoe McKenzieNessuna valutazione finora

- 1.the Global Environment of Business: New Paradigms For International ManagementDocumento14 pagine1.the Global Environment of Business: New Paradigms For International ManagementManvi AdlakhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Concept of Corporate PowerDocumento23 pagineConcept of Corporate PowerSaahiel SharrmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Swot Analysis InfosysDocumento17 pagineSwot Analysis InfosysAlia AkhtarNessuna valutazione finora

- Valuing Intellectual Capital: Multinationals and TaxhavensDa EverandValuing Intellectual Capital: Multinationals and TaxhavensNessuna valutazione finora

- 3-Market Integration-The Rise of Global CorporationsDocumento33 pagine3-Market Integration-The Rise of Global CorporationsERIKA REYESNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporate Disclosure and The Deregulation of International InvestmentDocumento22 pagineCorporate Disclosure and The Deregulation of International InvestmentarizulfaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Influence of Political and Legal Challenges Facing MNCDocumento10 pagineThe Influence of Political and Legal Challenges Facing MNCjigar0987654321Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 3Documento17 pagineChapter 3yimenueyassuNessuna valutazione finora

- Multinational Corporations and The Erosion of State SovereigntyDocumento4 pagineMultinational Corporations and The Erosion of State SovereigntyPolar Ice100% (1)

- Globalization Vs LocalizationDocumento5 pagineGlobalization Vs Localizationrushin202003Nessuna valutazione finora

- 3 Market Integration The Rise of Global Corporations 30Documento30 pagine3 Market Integration The Rise of Global Corporations 30genesis victorinoNessuna valutazione finora

- MNC or Multinational CorporationDocumento26 pagineMNC or Multinational CorporationTanzila khan100% (6)

- People Over Profit - ConceptDocumento3 paginePeople Over Profit - ConceptAlex AlegreNessuna valutazione finora

- Poli Econ EssayDocumento8 paginePoli Econ EssayhelmasryNessuna valutazione finora

- Major Difference Between Domestic and International BusinessDocumento4 pagineMajor Difference Between Domestic and International BusinessSakshum JainNessuna valutazione finora

- Write A Short Note On MNCS?Documento2 pagineWrite A Short Note On MNCS?Ritesh KhandelwalNessuna valutazione finora

- Notes On Book 5Documento11 pagineNotes On Book 5HazemNessuna valutazione finora

- Cross Body MergersDocumento7 pagineCross Body MergersIrtaqa RazaNessuna valutazione finora

- Stakeholders and Sustainable Corporate Governance in NigeriaDocumento154 pagineStakeholders and Sustainable Corporate Governance in NigeriabastuswitaNessuna valutazione finora

- International Efforts To Improve Corporate Governance: Why and HowDocumento15 pagineInternational Efforts To Improve Corporate Governance: Why and HowSidharth ShekharNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporate Governance and The Public Interest: Department of EconomicsDocumento31 pagineCorporate Governance and The Public Interest: Department of EconomicsreenuramanNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 5 Directed StudiesDocumento28 pagineModule 5 Directed StudiesDeontray MaloneNessuna valutazione finora

- State of Power 2015: An Annual Anthology on Global Power and ResistanceDa EverandState of Power 2015: An Annual Anthology on Global Power and ResistanceNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal CorporateDocumento16 pagineJurnal CorporateRatih Frayunita SariNessuna valutazione finora

- What Are The Challenges For The Multi-National Corporations On Account of Intensification of The Divide Between Pro-Globalists and Anti-Globalists?Documento5 pagineWhat Are The Challenges For The Multi-National Corporations On Account of Intensification of The Divide Between Pro-Globalists and Anti-Globalists?MOULI BANERJEE MBA IB 2018-20 (DEL)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 6Documento11 pagineUnit 6HABTEMARIAM ERTBANNessuna valutazione finora

- Daniel Aguirre EngDocumento36 pagineDaniel Aguirre EngEngr Ayaz KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Conworl MidtermsDocumento8 pagineConworl Midtermscl4rr3znNessuna valutazione finora

- Role of Multi National Companies in India: EconomicsDocumento4 pagineRole of Multi National Companies in India: EconomicsRockyLagishettyNessuna valutazione finora

- Policy Paper 2Documento5 paginePolicy Paper 2Irene ArieputriNessuna valutazione finora

- Governance Issues in Economic SocietyDocumento20 pagineGovernance Issues in Economic SocietycurlicueNessuna valutazione finora

- Trade and Competitiveness Global PracticeDa EverandTrade and Competitiveness Global PracticeValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Palgrave Macmillan JournalsDocumento19 paginePalgrave Macmillan JournalsAbubakar IlyasNessuna valutazione finora

- Scenario 1Documento19 pagineScenario 1Munib SiddiquiNessuna valutazione finora

- 1: Defining Local Economic Development and Why Is It Important?Documento14 pagine1: Defining Local Economic Development and Why Is It Important?jessa mae zerdaNessuna valutazione finora

- Global Business Environment - Evolution and Dynamics 1Documento6 pagineGlobal Business Environment - Evolution and Dynamics 1Meshack MateNessuna valutazione finora

- MNCs Role in Underdeveloped CountriesDocumento31 pagineMNCs Role in Underdeveloped CountriesNainaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter2 - The New Trends of The Global EconomyDocumento15 pagineChapter2 - The New Trends of The Global Economyagatha linusNessuna valutazione finora

- IB Project - HR - TYBBI - Roll No.44Documento12 pagineIB Project - HR - TYBBI - Roll No.44Mita ParyaniNessuna valutazione finora

- A Multinational EnterpriseDocumento12 pagineA Multinational EnterpriseKevin ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Entrepreneurship and Innovation - Organizations, Institutions, Systems and RegionsDocumento23 pagineEntrepreneurship and Innovation - Organizations, Institutions, Systems and Regionsdon_h_manzanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 2 WorksheetsDocumento8 pagineUnit 2 WorksheetsDaniela Sison DimalaluanNessuna valutazione finora

- Salazar Research#2Documento5 pagineSalazar Research#2Darren Ace SalazarNessuna valutazione finora

- Institutional Reform Foreign Direct Investment and European Transition EconomiesDocumento27 pagineInstitutional Reform Foreign Direct Investment and European Transition Economiesimaneamani993Nessuna valutazione finora

- Unit - VDocumento23 pagineUnit - Vperiyasamy.pnNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is A Multinational Corporation (MNC) ?: Key Issues in International Business StrategyDocumento6 pagineWhat Is A Multinational Corporation (MNC) ?: Key Issues in International Business StrategyShubham AgrawalNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is CGDocumento20 pagineWhat Is CGZohaib HassanNessuna valutazione finora

- Challenges of Multinational Companies A1Documento6 pagineChallenges of Multinational Companies A1Glydel Anne C. LincalioNessuna valutazione finora

- Mita Paryani: International Business ProjectDocumento12 pagineMita Paryani: International Business ProjectSunny AhujaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pertemuan 3 (9, 10, 13)Documento3 paginePertemuan 3 (9, 10, 13)ivantbNessuna valutazione finora

- Individual Project I.B.Documento6 pagineIndividual Project I.B.Nimanshi JainNessuna valutazione finora

- ITF (Transnational Corporations)Documento17 pagineITF (Transnational Corporations)Umair Ahmed AndrabiNessuna valutazione finora

- Globalisation Is Radically Changing The International Business Environment by Creating ADocumento18 pagineGlobalisation Is Radically Changing The International Business Environment by Creating ADeshan1989Nessuna valutazione finora

- Business Dealings in Emerging Economies, Non-Contractual Relations, and Recourse To Law - An AnalysisDocumento12 pagineBusiness Dealings in Emerging Economies, Non-Contractual Relations, and Recourse To Law - An AnalysisAnish GuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter ThreeDocumento34 pagineChapter ThreeyimenueyassuNessuna valutazione finora

- Impactof Multinational Corporationson Developing CountriesDocumento18 pagineImpactof Multinational Corporationson Developing CountriesRoman DiuţăNessuna valutazione finora

- AN610 - Using 24lc21Documento9 pagineAN610 - Using 24lc21aurelioewane2022Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 11 Walter Nicholson Microcenomic TheoryDocumento15 pagineChapter 11 Walter Nicholson Microcenomic TheoryUmair QaziNessuna valutazione finora

- Erickson Transformer DesignDocumento23 pagineErickson Transformer DesigndonscogginNessuna valutazione finora

- Technical Manual: 110 125US 110M 135US 120 135UR 130 130LCNDocumento31 pagineTechnical Manual: 110 125US 110M 135US 120 135UR 130 130LCNKevin QuerubinNessuna valutazione finora

- Sigma Valve 2-WayDocumento2 pagineSigma Valve 2-WayRahimNessuna valutazione finora

- Brother Fax 100, 570, 615, 625, 635, 675, 575m, 715m, 725m, 590dt, 590mc, 825mc, 875mc Service ManualDocumento123 pagineBrother Fax 100, 570, 615, 625, 635, 675, 575m, 715m, 725m, 590dt, 590mc, 825mc, 875mc Service ManualDuplessisNessuna valutazione finora

- NYLJtuesday BDocumento28 pagineNYLJtuesday BPhilip Scofield50% (2)

- Global Review Solar Tower Technology PDFDocumento43 pagineGlobal Review Solar Tower Technology PDFmohit tailorNessuna valutazione finora

- The Website Design Partnership FranchiseDocumento5 pagineThe Website Design Partnership FranchiseCheryl MountainclearNessuna valutazione finora

- Pradhan Mantri Gramin Digital Saksharta Abhiyan (PMGDISHA) Digital Literacy Programme For Rural CitizensDocumento2 paginePradhan Mantri Gramin Digital Saksharta Abhiyan (PMGDISHA) Digital Literacy Programme For Rural Citizenssairam namakkalNessuna valutazione finora

- ODF-2 - Learning MaterialDocumento24 pagineODF-2 - Learning MateriallevychafsNessuna valutazione finora

- Qa-St User and Service ManualDocumento46 pagineQa-St User and Service ManualNelson Hurtado LopezNessuna valutazione finora

- Annotated Portfolio - Wired EyeDocumento26 pagineAnnotated Portfolio - Wired Eyeanu1905Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sem 4 - Minor 2Documento6 pagineSem 4 - Minor 2Shashank Mani TripathiNessuna valutazione finora

- Nasoya FoodsDocumento2 pagineNasoya Foodsanamta100% (1)

- Medical Devices RegulationsDocumento59 pagineMedical Devices RegulationsPablo CzNessuna valutazione finora

- 1.2 The Main Components of Computer SystemsDocumento11 pagine1.2 The Main Components of Computer SystemsAdithya ShettyNessuna valutazione finora

- Teralight ProfileDocumento12 pagineTeralight ProfileMohammed TariqNessuna valutazione finora

- Aisc Research On Structural Steel To Resist Blast and Progressive CollapseDocumento20 pagineAisc Research On Structural Steel To Resist Blast and Progressive CollapseFourHorsemenNessuna valutazione finora

- Incoterms 2010 PresentationDocumento47 pagineIncoterms 2010 PresentationBiswajit DuttaNessuna valutazione finora

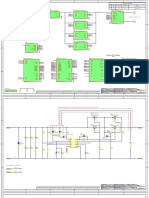

- Scheme Bidirectional DC-DC ConverterDocumento16 pagineScheme Bidirectional DC-DC ConverterNguyễn Quang KhoaNessuna valutazione finora

- INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS DYNAMIC (Global Operation MGT)Documento7 pagineINTERNATIONAL BUSINESS DYNAMIC (Global Operation MGT)Shashank DurgeNessuna valutazione finora

- Vocabulary Practice Unit 8Documento4 pagineVocabulary Practice Unit 8José PizarroNessuna valutazione finora

- Mathematical Geophysics: Class One Amin KhalilDocumento13 pagineMathematical Geophysics: Class One Amin KhalilAmin KhalilNessuna valutazione finora

- Installation Manual EnUS 2691840011Documento4 pagineInstallation Manual EnUS 2691840011Patts MarcNessuna valutazione finora

- U2 - Week1 PDFDocumento7 pagineU2 - Week1 PDFJUANITO MARINONessuna valutazione finora

- ARISE 2023: Bharati Vidyapeeth College of Engineering, Navi MumbaiDocumento5 pagineARISE 2023: Bharati Vidyapeeth College of Engineering, Navi MumbaiGAURAV DANGARNessuna valutazione finora

- IIBA Academic Membership Info-Sheet 2013Documento1 paginaIIBA Academic Membership Info-Sheet 2013civanusNessuna valutazione finora

- Tank Emission Calculation FormDocumento12 pagineTank Emission Calculation FormOmarTraficanteDelacasitosNessuna valutazione finora

- Strategic Management ModelsDocumento4 pagineStrategic Management ModelsBarno NicholusNessuna valutazione finora