Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

German Economy

Caricato da

Raj ChaDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

German Economy

Caricato da

Raj ChaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

German economy: Optimism amidst the slowdown

They're an optimistic lot, the Germans. Rarely more so, in fact. Greece may be burning. Growth may be slowing. The talk elsewhere may be of a return to the 1930s. But the recognized German barometer of hope over fear shows far more Germans looking on the bright side than those down in the dumps. According to the Allensbach Institute, which has tracked these things rigorously since 1949, 49% polled said they were hopeful of the future, compared with 17% who were fearful. That's pretty well three smiles to every frown (with 26% showing some scepticism and 8% undecided). Are Germans happy with the way they are being led? Yes, they are - very much so. On the latest opinion polls, two of every three Germans said Chancellor Angela Merkel was doing a good job. Three-quarters think she is taking "correct and decisive action" in the eurozone crisis. It's a glowing picture of satisfaction by the citizenry that stems from the economy. Unemployment is falling. German exports grew more than 10% last year. In 2010 and 2011, the economy grew at nearly 4% and last year at 3%, more than decent by European standards. Latest figures show that it slowed at the end of 2011. The indications are that this year it will grow by about 0.5% - measly by recent standards, but far from the recession expected elsewhere. Thinking ahead So what's behind the robustness? China, in a word. And "manufacturing", in another. The growth of China is fuelling demand by the Chinese new rich for BMWs and demand by Chinese factories for German machinery. This isn't a fluke. German industrialists foresaw the potential of China when most others saw only turbulence and trouble. In October 1975 - 37 years ago, when China was in the chaos of the Cultural Revolution - the Financial Times described German policy towards the country: "China could be the next growth market". Talk about long-term thinking. In ultra-unlikely circumstances - where Chairman Mao was excoriating capitalism and the new Chinese constitution talked of a "dictatorship of the proletariat" - German capitalists had identified the big new market: the People's Republic of China. Angela Merkel may look stern, but her people are smiling

"The West German approach is typical of the very long-range view that German industry has taken," said the FT. "At the heart of the approach lies the cultivation of a market, even if the short-term results are not overencouraging." Or take this from Die Zeit in the same year: "The image which Germany is trying to project in the largest and most populous developing country in the world is not that of a major political power, but rather of the most important industrial country in the world, a country whose tool-making and mechanical engineering can compete successfully on the world market." In 1975, British industry was in its perpetual state of crisis at the time, gearing up for what would be the general strike of the Winter of Discontent. The US economy was in recession. But German industrialists were thinking of China as the future. Social goals Why did they see it when others didn't? Dr Olaf Ploetner of the European School of Management and Technology in Berlin says that the key decisions were often taken by particular chief executives with vision, but they worked within a German framework of long-term views. Contribution to society is always a very important point Firstly, German industry isn't particularly profitable. There isn't that high a return in manufacturing, because making cars or machinery demands much costly investment and research and development. Dr Ploetner told the BBC that this forces companies into looking far ahead. They live on a lower rate of profit, but for a longer period of solidity. "It's interesting that they can exist for so long with small profits," he said, "and this is to do with the owners." Because a large part of German industry is family-owned, the short-term demands of shareholders, who want quick and relentless rises in the prices of shares, do not matter. Many German firms, too, are owned by "foundations", often set up by the company's first generation of family founders. A foundation is an entity which owns something - like a company - but which is not owned by individuals. The Robert Bosch Foundation, for example, owns 92% of Bosch, the giant engineering company. But the goals of the Robert Bosch Foundation are partly philanthropic, so it doesn't act as profit-maximising shareholders might. As Dr Ploetner puts it: "All the big companies are organised in foundations, and the foundations do not have 'return on capital employed' as their most important goal. Contribution to society is always a very important point."

It doesn't mean that German companies are charities. But it does mean that German companies are less easily swayed by the vagaries of the moment. Combine that with a very decentralised economy, and you have the picture of solid and steady prosperity. Hidden champions If you go to virtually any German small town, there is a good chance that on the outskirts will be a middle-sized family firm which, in its own field, will be in the top three in the world. That could be anything from making the cranes for docks, to the glue for embedding the different parts of credit cards together, to making bronze propellers for the world's biggest ships. Or to making pumps for concrete. But herein, perhaps, lies an omen. Putzmeister is one of Germany's "hidden champions" - a company that leads the world in its niche. It was founded by Karl Schlecht near Stuttgart in 1958. Schlecht designed a pump and then turned the idea into a company that went on to lead the market. Karl Schlecht has just sold this German "hidden champion" - to a Chinese company. It has caused ructions among his employees, who are outraged because it came out of the blue. They protested outside the factory in Swabia. And it's caused much angst beyond, too. Germans wonder if their great success story is about to be completed - with a Chinese ending.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Ulta Beauty Hiring AgeDocumento3 pagineUlta Beauty Hiring AgeShweta RachaelNessuna valutazione finora

- Hassan I SabbahDocumento9 pagineHassan I SabbahfawzarNessuna valutazione finora

- Rong Sun ComplaintDocumento22 pagineRong Sun ComplaintErin LaviolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Scott Kugle-Framed, BlamedDocumento58 pagineScott Kugle-Framed, BlamedSridutta dasNessuna valutazione finora

- California Department of Housing and Community Development vs. City of Huntington BeachDocumento11 pagineCalifornia Department of Housing and Community Development vs. City of Huntington BeachThe Press-Enterprise / pressenterprise.comNessuna valutazione finora

- Surviving Hetzers G13Documento42 pagineSurviving Hetzers G13Mercedes Gomez Martinez100% (2)

- Proposed Food Truck LawDocumento4 pagineProposed Food Truck LawAlan BedenkoNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter (2) Industry and Competitive AnalysisDocumento16 pagineChapter (2) Industry and Competitive Analysisfsherif423Nessuna valutazione finora

- Richard K. Neumann JR., J. Lyn Entrikin - Legal Drafting by Design - A Unified Approach (2018) - Libgen - LiDocumento626 pagineRichard K. Neumann JR., J. Lyn Entrikin - Legal Drafting by Design - A Unified Approach (2018) - Libgen - LiEwertonDeMarchi100% (3)

- Lunacy in The 19th Century PDFDocumento10 pagineLunacy in The 19th Century PDFLuo JunyangNessuna valutazione finora

- Part I Chapter 1 Marketing Channel NOTESDocumento25 paginePart I Chapter 1 Marketing Channel NOTESEriberto100% (1)

- S0260210512000459a - CamilieriDocumento22 pagineS0260210512000459a - CamilieriDanielNessuna valutazione finora

- Horizon Trial: Witness Statement in Support of Recusal ApplicationDocumento12 pagineHorizon Trial: Witness Statement in Support of Recusal ApplicationNick Wallis100% (1)

- Romeo and Juliet: Unit Test Study GuideDocumento8 pagineRomeo and Juliet: Unit Test Study GuideKate Ramey100% (7)

- Full Download Health Psychology Theory Research and Practice 4th Edition Marks Test BankDocumento35 pagineFull Download Health Psychology Theory Research and Practice 4th Edition Marks Test Bankquininemagdalen.np8y3100% (39)

- Satisfaction On Localized Services: A Basis of The Citizen-Driven Priority Action PlanDocumento9 pagineSatisfaction On Localized Services: A Basis of The Citizen-Driven Priority Action PlanMary Rose Bragais OgayonNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 2 - How To Calculate Present ValuesDocumento21 pagineChapter 2 - How To Calculate Present ValuesTrọng PhạmNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Money Supply On Economic Growth of BangladeshDocumento9 pagineImpact of Money Supply On Economic Growth of BangladeshSarabul Islam Sajbir100% (2)

- 4th Exam Report - Cabales V CADocumento4 pagine4th Exam Report - Cabales V CAGennard Michael Angelo AngelesNessuna valutazione finora

- 09 Task Performance 1-ARG - ZABALA GROUPDocumento6 pagine09 Task Performance 1-ARG - ZABALA GROUPKylle Justin ZabalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Why Study in USADocumento4 pagineWhy Study in USALowlyLutfurNessuna valutazione finora

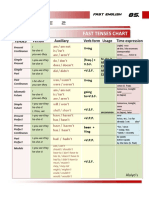

- Table 2: Fast Tenses ChartDocumento5 pagineTable 2: Fast Tenses ChartAngel Julian HernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- Account Number:: Rate: Date Prepared: RS-Residential ServiceDocumento4 pagineAccount Number:: Rate: Date Prepared: RS-Residential ServiceAhsan ShabirNessuna valutazione finora

- Allama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad: WarningDocumento3 pagineAllama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad: Warningمحمد کاشفNessuna valutazione finora

- Action Plan Templete - Goal 6-2Documento2 pagineAction Plan Templete - Goal 6-2api-254968708Nessuna valutazione finora

- Digest Pre TrialDocumento2 pagineDigest Pre TrialJei Essa AlmiasNessuna valutazione finora

- Union Africana - 2020 - 31829-Doc-Au - Handbook - 2020 - English - WebDocumento262 pagineUnion Africana - 2020 - 31829-Doc-Au - Handbook - 2020 - English - WebCain Contreras ValdesNessuna valutazione finora

- NEC Test 6Documento4 pagineNEC Test 6phamphucan56Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2020 Rattlers Fall Sports ProgramDocumento48 pagine2020 Rattlers Fall Sports ProgramAna CosinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Rotary HandbookDocumento78 pagineRotary HandbookEdmark C. DamaulaoNessuna valutazione finora