Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Information Strategy in Adhocratic Businesses

Caricato da

quicksilvrDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Information Strategy in Adhocratic Businesses

Caricato da

quicksilvrCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Information Strategy in Adhocratic Businesses

Dr Ernest Jordan Dept. of Information Systems City University of Hong Kong Tat Chee Avenue Kowloon, Hong Kong (currently at Macquarie Graduate School of Management) Email: EJordan@work.gsm.mq.edu.au

Abstract

An investigation has been carried out that examines the relationship between an organisation's structure and the information systems that support its operations. Twenty five business units in an international bank were studied in terms of organisational structure and information systems. This paper examines in detail the eight business units that were classified as adhocracies. End user computing was commonly used as the strategy for effectively using information technology in these units. A hypothesis derived from the work of Mintzberg was tested and found to be of limited usefulness.

1.

INTRODUCTION

The specific need to carry out strategic planning for the information systems (IS) and information technology (IT) infrastructure of the organisation became obvious in larger organisations as budgets increased and the impacts, both inside and outside the organisation, became more significant (Lederer and Mendelow, 1986; Brancheau and Wetherbe, 1987; Earl, 1989). The need increased for many when it appeared that competitors were able to achieve competitive advantage through these technologies (Wiseman and MacMillan, 1984; Porter and Millar, 1985). It was made even more pressing through the decentralisation and distribution of computer power that enabled user managers to dramatically change the ways in which their business activities were carried out (Lee, 1988; Lederer and Mendelow, 1988).

Initial approaches to the task of carrying out information systems strategic planning (ISSP) were simple models and frameworks that helped understanding and showed opportunities but did not lead to an implementable plan (McLean and Soden, 1977; King, 1978; Nolan, 1979). Since then many methodologies have been developed that will guide the user to an IT development portfolio (Earl, 1989; Lederer and Sethi, 1988). Most methodologies have been pragmatically developed and investigate three areas: business needs, an enhancement path for existing systems, and technology-driven opportunities. A common weakness is the technique for evaluation of alternative proposals created in the investigations. The need to ensure that the development plan fits with the organisation has also received little attention in the established methodologies (McFarlan, 1990).

ISSP remains complex, expensive and uncertain. Organisations that have carried out ISSP are not assured of success in developing applications of IT that will achieve competitive advantage (Earl et al., 1988). Conversely, organisations may develop successful applications without engaging in ISSP. Our aim is to provide IS

strategic planners with additional tools to enable them to carry out shorter, quicker strategic assessments and to enable them to evaluate more critically some of the proposals raised in the strategic planning process. In particular, planners should be able to evaluate the alignment of a potential application with the organisation's competitive strategy, and its compatibility with the way in which the organisation functions.

In looking for a theoretical foundation for ISSP, research results point towards an organisational role for information and a competitive or strategic role for information. While the competitive strategy approach has been widely researched (Sabherwal and King, 1991; Bergeron et al. 1991; Weill, 1990; for example), here we examine the contribution of organisational structure, which has been little considered (Tavakolian, 1989; Iivari, 1992).

2.

THE ORGANISATIONAL VIEW OF INFORMATION

Mintzberg's structural forms of organisations Here we extend the analysis of Leifer (1988) by carrying out a more detailed examination of the organisational structure. In his seminal work on organisational structures, Mintzberg (1979) breaks down any organisation into five basic parts: the strategic apex, middle line, operating core, technostructure and support staff; shown in Fig. 1. The operating core carries out the elementary functions of production of the organisation; it is supervised directly by the middle line, and the strategic apex includes senior management and members of the board. The technostructure consists of analysts, technologists and other specialists who are concerned with designing the work processes of others (mostly the operating core), generally to bring about standardisation. The support staff provide support to the organisation outside the flow of productive work; from legal services to canteens, print room to cleaners.

Strategic apex Technostructure Middle line Support staff

Operating core

Fig. 1 The Structural Components of the Organisation (Mintzberg, 1979)

Mintzberg describes five distinct ways that work may be coordinated, that are used depending upon the complexity and dynamic nature of the organisation's environment, and interdependencies of the work tasks being undertaken in the operating core; namely: direct supervision, standardisation of work processes, standardisation of outputs, standardisation of skills, and mutual adjustment.

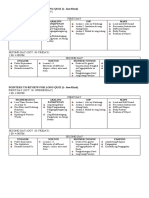

Each particular coordinating mechanism allows one of the basic parts to become the dominant, controlling part of the organisation. They are the strategic apex, technostructure, middle line, operating core and support staff, respectively. For each of them in turn, there is a corresponding form of the organisational structure, shown in Table 1. Mintzberg names the characteristic organisational structures as simple structure, machine bureaucracy, divisionalised form,

professional bureaucracy and adhocracy, respectively.

Control mechanism Direct supervision

Dominant part strategic apex

Structural form simple structure machine bureaucracy divisionalised form professional bureaucracy adhocracy

Standardisation of work processes technostructure Standardisation of outputs Standardisation of skills Mutual adjustment Table 1: The five structural forms middle line operating core support staff

Mintzberg's (1973) examination of the informational roles of the manager and his view of the organisation as a system of information flows (1979), give a picture of information in the organisation. Each of the above five basic configurations is considered in turn.

The simple structure has direct, two-way information flows between the operational employees and the strategic apex, with most of them being informal. There is little need for a formal management information system because most of it is in the mind of the senior management. With direct supervision being applicable to all the operational employees, there is no need for formal communications. Information gathering is elementary, with external regulators such as government taxation and labour departments being driving forces. Any systems will be centralised and functional.

The machine bureaucracy is appropriate for stable environments; when nonroutine decisions need to be made or exceptions arise, they need to be communicated up the hierarchy to someone with the level of authority to act. The management information system is designed with that principle in mind. Summary information also flows up to higher levels so that control can be exerted and decisions can be made; which decisions in turn flow down the organisation

(Mintzberg, 1979:342). If designed correctly, at each point in the hierarchy there is sufficient authority to deal with the normal amount of variation, so that only exceptions need to be passed on. However, in many cases, "normal" information is passed up to senior levels, a common pattern of excessive reporting. The vertical, both up and down, information flow is dominant but not the only one. There are horizontal flows of design and control information between the technostructure and the rest of the organisation (mainly the middle line) because it is the function of the technostructure to design and control work. The third group of flows are the information flows that follow the material flow and flow of work (Mintzberg, 1979:38), which exist also in the simple structure and divisionalised form. If the organisation only processes information, then the material flows are themselves information flows.

Mintzberg

characterises

the

divisionalised form

as

collection

of

organisational units, usually machine bureaucracies (Mintzberg, 1979:392), under the supreme control of the headquarters strategic apex. Thus the apex of each of the component divisions becomes the middle line in the overall organisation, passing up performance information for the purpose of control. Within each division, the information flows are those of a machine bureaucracy, except that the information requirement of the apex has been designed and specified by the technostructure at headquarters.

The managers there, with the aid of their own technostructure, set up the system: they decide on the performance measures and reporting periods, establish formats for plans and budgets, and design an MIS to feed performance results back to headquarters. They then operate the system, setting targets for each reporting period, perhaps jointly with the divisional managers, and reviewing the MIS results. (Mintzberg, 1979:390)

As an aside, this view gives clarity to the continuing debate (from Streeter, 1973; through Lucas, 1982; to Oppenheimer, 1991) in the IS field about centralisation or decentralisation of the MIS department. Should the organisation put its greatest investment in central computer resources or should the functional or user departments have responsibility for their own computing? In Mintzberg's terms, there must be a technostructure at headquarters involved in the design (and building) of the performance control system used for assessing divisions, while each division clearly needs authority to develop its own internal systems.

The professional bureaucracy is an organisation in which the standards used by the operating core are determined by outside professional bodies. Thus the technostructure does not develop a performance control system; the standards and techniques of the operating core have been established in the professional code and practice of their discipline. Each discipline has specialisations into which the task must be pigeon-holed; standard sets of conditions enable a diagnosis followed by a standard treatment pattern, learned during training. All the factors are in the hands of the profession, not the technostructure. Mintzberg (1979:361) suggests that a large, professional bureaucracy organisation will have a fully-developed support staff, which may well be itself organised as a machine bureaucracy; thus the technostructure can create MIS for the support staff rather than the operating staff. There will remain information flows that follow the flow of work but they will simply be enough to effect communication with the next professional in the chain, such as in the medical referral; the next professional is expected to know what to do.

The adhocracy has professionally trained staff, like the professional bureaucracy, but they are organised in organic teams to try to solve new problems, such as reported by Burns and Stalker (1966) in the British electronics industry.

Within the teams, which are usually project-based, will be managers and support staff. Liaison groups will be widely used to effect coordination between groups, with mutual adjustment used within the group. Formal IS that regulate and control are not important:

The regulated system does not matter much either. In this structure, information and decision processes flow flexibly and informally, wherever they must to promote innovation. And that means overriding the chain of command if needs be. (Mintzberg, 1979:473)

There are two variants of the adhocracy - the administrative adhocracy that is concerned with problems belonging to the organisation itself, and the operating adhocracy whose problems belong to outside clients or customers. Both the administrative and operating adhocracies are decentralised such that control is within the project teams, the manager being part of the team. There is no organisation wide control system; each team has goals of its own.

The preceding sections demonstrate that the nature and role of information is central to the study of organisations, and, just as emphatically, that the organisational structure and managerial roles are critical ingredients in the selection, analysis and design of IS. As a consequence, IS are implicitly associated with organisational change, as Keen (1981) pointed out. Changes in the organisation can be dealt with in an information model by examining the organisational structure.

The organisational structure model of Mintzberg facilitates the understanding of information in the organisation, particularly through its examination of the flows of information, decisions and control. It is also amenable to empirical investigation.

3.

THE RESEARCH HYPOTHESES

In this section a hypothesis is developed by considering the impact of organisation structure on IS using the theories of Mintzberg. The fundamental functioning of the organisational structure is examined to attempt to define the generic information system that would be appropriate for it. A set of contingency factors determines the method of coordination (Mintzberg, 1979:286) and in turn determines the organisational structure and the functioning of the organisation. The contingency factors are:

the age and size of the firm, the technical system, the environment, and the centre of power.

In terms of IT, the contingency factors that are most significant are the technical system and the environment. The technical system refers to the means of production, whether it is simple or sophisticated and whether the technology of production controls the work of the operating core or not. Fully automated production dispenses with the need for an operating core, while very simple production technology (cooking hamburgers) is standardised. The organisation's operating environment has four key attributes stability, simplicity, market diversity and hostility:

Stability leads to predictability that in turn leads to standardisation; Simplicity leads to rationalisation and the analysis of operational work

into easily comprehensible segments by the technostructure;

Increasing diversity of markets increases the range of work to be

done; and

Hostility leads to unpredictability and the need for fast strategic

actions.

Furthermore, the interaction between the environment and the technical system is concerned with the rate of change of the technical system (Mintzberg, 1979:250). The relationship between the environment, the technical systems and IT is through the information content of the technical system and of the product, and the rate of change of the applicable IT. That is, the four attributes of environment and the two attributes of technical system are strongly related to IT.

Hypothesis MAD The generic information system for the adhocracy is the network; local area networks to support the small-size unit focused on a particular function or market, and larger networks to facilitate liaison and coordination among larger groupings. The networks mimic, supplement and support the human networks that are an essential part of the adhocracy. The software on the network should vary significantly, although there is a need for some transferability and transportability. The criterion for selection of the software will be the extent to which it supports and enhances the performance of the team; in other words, the software may have to be regarded as another team member. Mintzberg identifies "non regulating and unsophisticated technical systems" as the hallmark of the operating adhocracy. An administrative adhocracy will have an information system incorporated in the background production process; it may be as explicit information or as control and monitoring information built into hardware devices.

4.

METHODOLOGY

An in-depth investigation was carried out on the strategic business units of a multinational financial institution, referred to here as "Globalbank". It has pursued a

10

policy of aggressively using IT as a strategic weapon with the aim of becoming more successful in an increasingly competitive marketplace. Its practice of

decentralisation of business units has enabled those units to pursue strategies that are almost independent, to such an extent that the business units can be regarded as distinct entities with a small set of organisational constraints. Thus the internal business units of Globalbank will serve as separate implementations of IT strategy, as a large sample rather than just one of size one. In addition, through its innovation and aggressive searching for IT opportunities, Globalbank can serve as a model for other organisations. That is, if an organisation can be successful in the application of IT, Globalbank has both had the opportunity and taken it.

Public IT strategy the historic drive for IT Globalbank is seen by authoritative commentators as a leader in the application of IT to banking, a position that it has held for many years. It adopted technology leadership as a strategic move in order to become more successful. As an example of its leadership, it introduced a communications network into its IT architecture long before most of its competitors; it was a strategic move that indicated its aim to expand the marketplace in which it operated. The establishment cost of the network was very large, comparable to the costs experienced by dedicated communications companies. The perception of strength is not only held externally but also internally; for example, its annual reports repeatedly refer to IT as one of the strengths of the organisation.

Globalbank has given great emphasis to IT over so long a period that the impacts of IT on the business, if any, will have been felt. There have been opportunities and encouragement to use IT to its greatest advantage. An IT strategy, then, has been implemented. The IT strategy can be observed through its implementation, and its effects and characteristics related to each other.

11

Globalbank has many distinct business units, each of which has had considerable freedom in determining its own IT strategies. They will be taken to be a large sample of experimental units, or, more precisely, test cases. Globalbank has an acknowledged position of leadership in its industry, particularly in the application of IT for competitive advantage. Globalbank managers are expected to be aggressive in using IT wherever it is beneficial in their domain. In such a setting there is the opportunity to assess many possibly successful users of IT, to determine whether the theories of Mintzberg suitably describe the information strategy.

The generally smaller size of the business units makes it harder to see the natural style of coordination. A business unit may look, at first sight, as if it is a simple structure, just a small business. On closer inspection, the degree of professionalism, specialisation, level of routine work and coordination with other groups indicates another form of structure. In the case of Globalbank, the separate business units vary greatly in size but only in the case of the major groupings, such as Corporate, Consumer, and Private Banking, do the divisions resemble the massive units analysed by Chandler (1962), Rumelt (1974) and others.

Data collection and validation A schedule was established for interviewing managers of business units, using a semi-structured questionnaire. Supplementary information sources included

computer system documentation, internal communications and external materials, such as newspaper and journal articles. The sources are described in the following sections.

Interviews The principal data collection method was determined to be semi-structured interviews. The questionnaire is displayed in Appendix 1. Another aspect of the

12

study concerned the alignment with the competitive strategy of the business unit, so the questionnaire contains many items under this heading. The questionnaire was a compilation from many sources including Feeny et al. (1989), Mintzberg (1979, 1983, 1988), Porter (1980, 1985), Porter and Millar (1985), Davis and Olson (1985), Lucas (1986) and Dickson and Wetherbe (1985). The questionnaire was designed to be directly administered by the interviewer. Questions raised in one interview could be presented to another manager in a later interview.

The interview subjects were the managers of the various business units and, when applicable, the managers of the business groups. In a few cases where operating processes were unclear or unusual, junior staff were consulted for explanation. Those staff were not targets for the questionnaire, which was aimed at managers making recommendations for IS facilities to support their business strategy. The sequence of business units investigated was customer-oriented units and then product-oriented units. The two groups had only recently been merged into a single entity, and had some historical differences. It was decided to see all the customer-oriented units before approaching the others. At that time most of customer-oriented units were in a different building to the product-oriented units which made it also physically convenient to deal with them sequentially. After all the business units had been examined, the most senior managers were interviewed.

Internal documentation A wide variety of documents originating from inside Globalbank in Hong Kong was collected. It included IS documentation, ISSP documents, minutes of working meetings, inter-office memos, and formal reports dealing with IS. In addition, wider organisational material included organisation charts, standard business forms, internal publicity, recruitment and induction handouts, newsletters and company magazines.

13

External documentation As Globalbank is a major international organisation, references to it are frequently to be found in public media. A collection was made of newspaper reports and journal articles referring to Globalbank, especially from the South China Morning Post, which often had articles referring to the same major issues that had been revealed earlier in interviews. The newspaper was also a source for advertisements for Globalbank's services and for recruitment of staff. Major references were found in books, although they seldom referred to activity in Hong Kong. Similarly there were regular references in such sources as The Economist and Business Week. In addition to the more journalistic articles, there were highly formalised public documents such as annual reports to shareholders, returns to statutory authorities, and invitations to participate in financial instruments and share issues.

Summary Data collection and validation Very large quantities of data were collected from a variety of sources. Interviews with business managers were the focal point, where questions covered the business unit structure, its competitive strategy and the role for IT. Responses were corroborated by reference to other informants and other documentary information sources. Regular literature searches, scans of contemporary journalism, and internal Globalbank documentation were the main supporting sources.

5.

THE STRUCTURE AND ORGANISATION OF GLOBALBANK

Globalbank's main activities in Hong Kong are corporate, consumer and private banking. Corporate banking customers include businesses, government

departments and other banks. Each of the businesses reports to its own superiors at head office directly. Within each country, including Hong Kong, a committee coordinates certain activities and ensures that local legal requirements are met. However, the organisational structure is not hierarchical, it is a matrix based upon

14

customers, products and geography. Thus, in the "geography" dimension, each business also reports to a regional group, which in turn reports to head office. The product dimension of the structure becomes most apparent when looking within a business area. Although corporate banking customers are subdivided into smaller customer groups, there are product teams dedicated to providing and managing certain products, whichever customer is using them. The product teams may well cut across the boundaries between corporate, consumer and private banking. Product teams also have a reporting path to head office.

The effect of this structural arrangement is to break down Globalbank into many smaller businesses, each responsible for a small group of customers, products or geographical territories. It is described by Gonzalez and Mintzberg (1991) as the 'related diversifier' or 'shotgun' strategy, where a financial institution enters many business segments, with only loose links between them. A senior Globalbank headquarters executive describes it as a key strength, because the small business units are all available for expansion. The manager of each of the businesses will have the job of achieving the best performance for the unit, in cooperation with others. There are many committees and other opportunities for coordination and liaison between units. Further complication is added because the manager of one unit may well have responsibilities in another area and because the individual's set of responsibilities frequently change. Each of the individual business units has been able to develop in its own way, within the general constraints posed by the organisation.

The actual area of study is the Hong Kong corporate banking business, Corporate Banking Hong Kong (CBHK). Note - generic names will be used for business units and groups. Through decentralisation each unit in this business has had considerable freedom and opportunity to develop the IT that it needs. By studying the nature of each unit's activities and its use of IT, we can examine

15

various implementations of a single corporate policy. In this paper only those units that were found to be adhocratic in structure are reported. Those that are customeroriented, shown in Table 2, and those that are product-oriented, shown in Table 3.

Unit World Corporate Group Corporate Banking Unit China Table 2:

Code WCG CBU

Main Customers Multinationals

Typical Products Many

Major local companies Many Many

CHINA Joint ventures

A summary of the customer-oriented business units

Unit Treasury Marketing Corporate Finance Unit Project Finance Unit

Code Main customers TM CFU PFU Many

Products Money market, FX

Middle size manufacturers Corporate equity Large organisations Large organisations Multinationals Capital project finance Pension funds Tax management

Institutional Investment Mgt IIM Tax Management Unit Table 3: TMU

A summary of the product-oriented business units

IT services in the Asia-Pacific region The organisation of IT service provision mirrors the business units. The corporate, consumer and private banking organisations have their own IT services groups, and there is a regional group (Asia Pacific IT, APIT) which can support any unit, country or product. CBHK's IT group (ITG) carries out some systems development for APIT, and vice versa. Any unit in CBHK must seek the assistance of ITG for any of its IT requirements. If they are not provided directly by either APIT or ITG, one of these units will manage the project and ensure that it meets corporate standards and fits into the existing systems. However, to a great extent it is the responsibility of the

16

business unit to determine its own IT requirements and to decide on the amount of funds that may be allocated to new systems. It reinforces the notion of the decentralised business units being independent decision makers.

6.

ANALYSIS

Extended case descriptions for the units, including their IT functions, are available from the author by mail or electronic mail. Differences from the hypothesised forms need to be understood, either as "random" variation, reasonably insignificant differences, or as differences caused by some other factor that was not part of the experiment, or as faults in the hypothesis.

The adhocracy There are thus eight business units classified as adhocracies: World Corporate Group, WCG, China customers, Tax Management Unit, TMU, Treasury Marketing, TM, Corporate Banking Unit, CBU, Institutional Investment Management, IIM, Project Finance Unit, PFU, Corporate Finance Unit, CFU.

They are all operating adhocracies that deal with customers' problems. In all units professional staff are employed who use their skills more on unique cases or projects than on routine action, although there is some routine in all of their work. There is much dealing with other professional or expert staff in different domains of expertise. Creativity, originality and the ability to coordinate with other disciplines are key attributes for staff in these areas. Standard professional skills are used in all areas but a variation is found in WCG where Globalbank has created its own profession of the WCG specialist. They are only interchangeable with WCG specialists from other countries.

17

CBU and China are concerned with setting up business, while TM even has a transaction processing function in the unit. All units are concerned with the design and/or the marketing of products. CBU creates management information for its own use. There is little use of IT to directly support staff activities beyond the use of PCs to model alternative proposals. The Globalbank electronic mail network is used in all units to work with people in other locations. It is critical to the success of WCG, TMU, PFU and the China unit. The existence of an international telecommunications network permits the processing that WCG and the China unit bring to market. Specific software that enhances the functioning of the staff in used in TMU, IIM and TM, with the most sophisticated software used by any of the groups being in TMU. General purpose software, such as PC packages, is used for enhanced performance of PFU, CFU and WCG. Because CFU's networks extend outside Globalbank, a cellular telephone is used, one of the few used by any business unit. The Mintzberg hypothesis, MAD, is supported but it gives little explanation of the differences between the IT developments in the units. The strongest support for MAD is given in the China unit, WCG, PFU, CFU and TMU.

Results Overall then, MAD was not so well received. It is perhaps indicative of the competitive, dynamic and evolving nature of banking in the present era, that eight business units (out of 25) were found to be operating as adhocracies. None of the units rejected MAD, but the degree of support was seldom strong. Part of the weak support may be attributable to the paucity of specific testable statements in MAD. Apart from the notion of networking and interaction with other experts, there are few concrete statements. End-user computing (Arkush and Stanton, 1987) was observed to be an important ingredient in the adhocracy. MAD was insufficiently authoritative to carry out robust testing. It gave a flavour of the information processing in an adhocracy but was very light on details, except for the concept of networking. End-user computing was highly developed in the adhocracies, and in

18

different ways in different units, but the hypothesis makes no proposals that could be tested.

7.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The general problem for an organisation to decide in which areas to develop IS and IT may be approached through ISSP. A body of knowledge and experience suggests that the best information strategy depends on many organisational and environmental factors. The alignment of IS strategy with the business needs has been an important issue to many organisations in their adoption of ISSP. The starting point of this investigation is that the business need must be moderated by the organisational structure in order to best determine the IS strategy.

The existing literature in IS development is particularly concerned with the problems of big business and the design of IS to suit their needs. Most such organisations would be classified as machine bureaucracies or divisionalised forms. Elsewhere in the study (Jordan, 1993) we have found that their generic IS descriptions suggested by Mintzberg are strongly supported. Similarly, the professional bureaucracies follow the hypothesised descriptions well, although there is significant variation among them. Units organised as simple structures are not so simple as theory suggests. The many reasons that may be behind the adoption of the simple structure form lead to major differences in IS needs. For such units, conclusive results have not been found beyond the inadequacy of existing theories.

However, we have found that simply considering Mintzberg's theory is insufficient to deal with a form of organisational structure that is becoming more common, the adhocracy. Our results show that this organically functioning, creative business unit benefits from a wide variety of information technologies, most

19

particularly networks and small systems and models developed by the users enduser computing.

8.

REFERENCES

Arkush, E. and Stanton, S.A. (1987) Third-Era Information Systems: Strategy Development Continued, Journal Information Systems Management, Spring, 66-69. Bergeron, F., Buteau, C. and Raymond, L. (1991) Identification of Strategic Information Systems Opportunities: Applying and Comparing Two Methodologies, MIS Quarterly, 15, 1, 89-103. Brancheau, J.C. and Wetherbe, J.C. (1987) Key Issues in Information Systems Management, MIS Quarterly, 11, 1, 23-45. Burns, T. and Stalker, G.M. (1966) The Management of Innovation (2nd ed.), Tavistock Publications: London. Chandler, A.D. Jr (1962) Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the Industrial Enterprise, MIT Press: Cambridge, MA. Davis, G.B. and Olson, M. (1985) Management Information Systems: Conceptual Foundations, Structure, and Development (2nd ed.), McGraw-Hill: New York, NY. Dickson, G.W. and Wetherbe, J.C. (1985) The Management of Information Systems, McGraw-Hill: New York, NY. Earl, M.J. (1989) Management Strategies for Information Technology, Prentice Hall International: Hemel Hempstead. Earl, M.J., Feeny, D.F., Lockett, M. and Runge, D. (1988) Competitive Advantage Through Information Technology: Eight Maxims for Senior Managers, Multinational Business, 2, Summer, 15-21. Feeny, D.F., Earl, M.J. and Edwards, B.R. (1989) IS Arrangements to Suit Complex Organisations 1: An Effective IS Structure, Oxford Institute of Information Management, Working Paper. Gonzalez, M. and Mintzberg, H. (1991) Visualizing Strategies for Financial Services, McKinsey Quarterly, 2, 125-134. Iivari, J. (1992) The Organizational Fit of Information Systems, Journal of Information Systems, 2, 3-29.

20

Jordan, E. (1993) Information Strategy: A Model for Integrating Competitive Strategy, Organisational Structure and Information Systems, unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong. Keen, P.G.W. (1981) Information Systems and Organizational Change, Comm. ACM, 24, 1, 24-33. King, W.R. (1978) Strategic Planning for MIS, MIS Quarterly, 2, 1. Lederer, A.L. and Mendelow, A.L. (1986) Issues in Information Systems Planning, Information & Management, 11, 245-254. Lederer, A.L. and Mendelow, A.L. (1988) Information Systems Planning: Top Management Takes Control, Business Horizons, May-June, 73-78. Lederer, A.L. and Sethi, V. (1988) The Implementation of Strategic Information Systems Planning Methodologies, MIS Quarterly, 12, 3, 445-461. Lee, D.R. (1988) The Evolution of Information Systems and Technologies, Advanced Management Journal, 53, 3, 17-23. Leifer, R.P. (1988) Matching Computer-Based Information Systems with Organizational Structures, MIS Quarterly, 12, 1, 63-73. Lucas, H.C. Jr (1982) Alternative Structures for the Management of Information Processing, in: Goldberg, R. and Lorin, H. (eds) The Economics of Information Processing, Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, 55-61. Lucas, H.C. Jr (1986) Information Systems Concepts for Management (3rd ed.), McGraw-Hill: New York, NY. McFarlan, F.W. (1990) The 1990s: The Information Decade, Business Quarterly (Canada), 55, 1, 73-79. McLean, E.R. and Soden, J.V. (1977) Strategic Planning for MIS, WileyInterscience: New York, NY. Miller, D. (1986) Configurations of Strategy and Structure: Towards a Synthesis, Strategic Management Journal, 7, 233-249. Mintzberg, H. (1973) The Nature of Managerial Work, Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Mintzberg, H. (1979) The Structuring of Organizations: A Synthesis of the Research, Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Mintzberg, H. (1983) Structure in Fives: Designing Effective Organizations, PrenticeHall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

21

Mintzberg, H. (1988) The Structuring of Organizations, in: Quinn, J.B., Mintzberg, H. and James, R.M. The Strategy Process: Concepts, Contexts and Cases, Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 276-303. Nolan, R.L. (1979) Managing the Crises in Data Processing, Harvard Business Review, 57, 2, 115-126. Oppenheimer, D. (1991) Debate Swirls over IS Organizational Approaches, National Underwriter, 95, 7, 56-57. Porter, M.E. and Millar, V.E. (1985) How Information Gives You Competitive Advantage, Harvard Business Review, 63, 4, 149-160. Porter, M.E. (1980) Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors, The Free Press: New York, NY. Porter, M.E. (1985) Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, The Free Press: New York, NY. Rumelt, R.P. (1974) Strategy, Structure and Economic Performance (reprinted 1986) Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA. Sabherwal, R. and King, W.R. (1991) Towards a Theory of Strategic Use of Information Resources: An Inductive Approach, Information & Management, 20, 191-212. Streeter, D.N. (1973) Centralisation or Dispersion of Computing Facilities, IBM Systems Journal, 12, 3, 283-301. Tavakolian, H. (1989) Linking the Information Technology Structure with Organizational Competitive Strategy: A Survey, MIS Quarterly, 13, 3, 309-317. Weill, P. (1990) Strategic Investment in Information Technology: An Empirical Study, Information Age, 12, 3, 141-147. Wiseman, C. and MacMillan, I.C. (1984) Creating Competitive Weapons from Information Systems, Journal Business Strategy, 5, Fall, 42-49.

22

APPENDIX 1 - Structured Interview Questionnaire

STRUCTURE

Questions to determine structure category: Key coordination mechanisms? direct supervision, standardisation (work, skills, outputs) or mutual adjustment Specific questions about all of Mintzberg's design parameters specialisation of jobs training and indoctrination formalisation of behaviour planning and control systems liaison devices decentralisation Contingency factors affecting design age size technical systems environment power

Check questions to verify that deduction is correct: Actual functioning in 5 parts characteristics of fundamental flows and work constellations response to tentative deduction

Questions relating to other organisational structure theories: Checking limit of applicability

23

MARKETING POSITION AND STRATEGY

Questions to determine competitive strategy: What is industry in which they operate? Is it one market or many?

Specific questions about industry forces Strength of force from: competitors entry barriers customers suppliers substitute products

Questions to verify that tentative deduction is correct: Response to tentative deduction market position statistics market share data

Questions relating to alternative theories: Limits of applicability

24

INFORMATION SYSTEMS

IS DEFINITION IS department organisation (staffing, groups, reporting, ...) Hardware installed and planned, value Software installed and planned, dates, User participation Tools, techniques, methodologies Performance measures used

IS STRATEGY Explicit strategy? People and processes for determining the strategy Review mechanism and timing Scope of strategy statement hardware software priorities etc. Perceived importance of this strategy within IS function Perceived importance of this strategy outside IS function

ALIGNMENT OF IS STRATEGY AND BUSINESS STRATEGY Examples of strategic advantage? Examples relating directly to market forces These examples - what percentage of total IS resource used? Project justification process used

25

PERCEIVED CONTRIBUTION OF IS TO ORGANISATION'S SUCCESS Is the organisation seen as successful? How is this determined? How does IS contribute? By IS manager By CEO

IS SWOT ANALYSIS Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats What are IS department's strengths? What are IS department's weaknesses? What opportunities exist with new technology now available? Other opportunities? What threats exist with new technology now available? Other threats?

26

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Teach Yourself Complete GermanDocumento187 pagineTeach Yourself Complete Germanquicksilvr93% (30)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Spark Charts - German GrammarDocumento6 pagineSpark Charts - German Grammarquicksilvr100% (21)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Brewers of Europe - Beer Statistics 2010Documento32 pagineThe Brewers of Europe - Beer Statistics 2010quicksilvrNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Best Practice: Campaign Management For Marketing ProfessionalsDocumento46 pagineBest Practice: Campaign Management For Marketing ProfessionalsquicksilvrNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Best Practice: Campaign Management For Marketing ProfessionalsDocumento46 pagineBest Practice: Campaign Management For Marketing ProfessionalsquicksilvrNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Kincade 2010Documento12 pagineKincade 2010varghees johnNessuna valutazione finora

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- QB ManualDocumento3 pagineQB ManualJCDIGITNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- SPUBSDocumento6 pagineSPUBSkuxmkini100% (1)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The IS - LM CurveDocumento28 pagineThe IS - LM CurveVikku AgarwalNessuna valutazione finora

- Westernization of East Asia: Asian Civilizations II Jervy C. Briones Lecturer, Saint Anthony Mary Claret CollegeDocumento29 pagineWesternization of East Asia: Asian Civilizations II Jervy C. Briones Lecturer, Saint Anthony Mary Claret CollegeNidas ConvanterNessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Asian Marketing Management: Biti's Marketing Strategy in VietnamDocumento33 pagineAsian Marketing Management: Biti's Marketing Strategy in VietnamPhương TrangNessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- EPLC Annual Operational Analysis TemplateDocumento8 pagineEPLC Annual Operational Analysis TemplateHussain ElarabiNessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Charles Simics The World Doesnt End Prose PoemsDocumento12 pagineCharles Simics The World Doesnt End Prose PoemsCarlos Cesar ValleNessuna valutazione finora

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Devel Goth ArchDocumento512 pagineDevel Goth ArchAmiee Groundwater100% (2)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- John Zietlow, D.B.A., CTPDocumento11 pagineJohn Zietlow, D.B.A., CTParfankafNessuna valutazione finora

- IRA Green BookDocumento26 pagineIRA Green BookJosafat RodriguezNessuna valutazione finora

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Ethics BSCE 2nd Sem 2023 2024Documento12 pagineEthics BSCE 2nd Sem 2023 2024labradorpatty2003Nessuna valutazione finora

- Pointers To Review For Long QuizDocumento1 paginaPointers To Review For Long QuizJoice Ann PolinarNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- SynopsisDocumento15 pagineSynopsisGodhuli BhattacharyyaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Glass Menagerie - Analytical EssayDocumento2 pagineThe Glass Menagerie - Analytical EssayJosh RussellNessuna valutazione finora

- The Technical University of KenyaDocumento46 pagineThe Technical University of KenyaBori GeorgeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Submission NichDocumento5 pagineSubmission NichMankinka MartinNessuna valutazione finora

- Portable IT Equipment PolicyDocumento3 paginePortable IT Equipment PolicyAiddie GhazlanNessuna valutazione finora

- Survey ChecklistDocumento4 pagineSurvey ChecklistAngela Miles DizonNessuna valutazione finora

- 6 Surprising Ways To Beat The Instagram AlgorithmDocumento5 pagine6 Surprising Ways To Beat The Instagram AlgorithmluminenttNessuna valutazione finora

- Google Diversity Annual Report 2019Documento48 pagineGoogle Diversity Annual Report 20199pollackyNessuna valutazione finora

- Hip Self Assessment Tool & Calculator For AnalysisDocumento14 pagineHip Self Assessment Tool & Calculator For AnalysisNur Azreena Basir100% (9)

- Domain of Dread - HisthavenDocumento17 pagineDomain of Dread - HisthavenJuliano Barbosa Ferraro0% (1)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- ACCA - Generation Next - Managing Talent in Large Accountancy FirmsDocumento34 pagineACCA - Generation Next - Managing Talent in Large Accountancy FirmsIoana RotaruNessuna valutazione finora

- Problem Set 1Documento2 pagineProblem Set 1edhuguetNessuna valutazione finora

- When The Artists of This Specific Movement Gave Up The Spontaneity of ImpressionismDocumento5 pagineWhen The Artists of This Specific Movement Gave Up The Spontaneity of ImpressionismRegina EsquenaziNessuna valutazione finora

- Example Research Paper On Maya AngelouDocumento8 pagineExample Research Paper On Maya Angelougw2wr9ss100% (1)

- Network Protocol Analyzer With Wireshark: March 2015Documento18 pagineNetwork Protocol Analyzer With Wireshark: March 2015Ziaul HaqueNessuna valutazione finora

- HR 2977 - Space Preservation Act of 2001Documento6 pagineHR 2977 - Space Preservation Act of 2001Georg ElserNessuna valutazione finora

- Admission Fee VoucherDocumento1 paginaAdmission Fee VoucherAbdul QadeerNessuna valutazione finora

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)