Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Trex 00026

Caricato da

OSDocs20120 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

26 visualizzazioni10 paginePERSONAL CONTROL methods are used by people to reduce inj uries, eliminate fatalities, and enable those people to accomplish their tasks more effectively. PERFORMANCE control techniques can be used to reduce injuries, prevent accidents, save lives, and increase production in high-risk businesoes.

Descrizione originale:

Titolo originale

TREX-00026

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoPERSONAL CONTROL methods are used by people to reduce inj uries, eliminate fatalities, and enable those people to accomplish their tasks more effectively. PERFORMANCE control techniques can be used to reduce injuries, prevent accidents, save lives, and increase production in high-risk businesoes.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

26 visualizzazioni10 pagineTrex 00026

Caricato da

OSDocs2012PERSONAL CONTROL methods are used by people to reduce inj uries, eliminate fatalities, and enable those people to accomplish their tasks more effectively. PERFORMANCE control techniques can be used to reduce injuries, prevent accidents, save lives, and increase production in high-risk businesoes.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 10

From: Wetherbee. James D.

Sent: Fri May 14 16:23 56 2010

To: Pagram, Bronwyn F

Subject: Exposure Reduction

Importance: Normal

Attachments: 8-Exposure Reduction Techn-9.doc

Pagram, tl1ank you for being interested. T look forward to continuing om over a long period of time, until

we take our company higher...

Jim Wi!therbee

BP Exploration Alaska

Mobile: +J (83:!) 205-1650

Office: +1 (907) 564-4551

CONFIDENTIAL

EXHIBIT# 1Jdf

WIT:

------

BP-HZN-BLY0009217 L!

EXPOSURE REDUCTION TECHNIQUES

12 April 2010

J. D. Wetherbee

Safety &Oper2t ions

Two kinds of control must be executed to manage risk: ORGANIZATIONAL CONTROL and PERSONAL CONTROL.

ORGANIZATIONAL CONTROL methods are developed and implemented by the leaders in the organization to help the

workforce conduct their jobs effectively by staying safe and working productively. In BP, these methods are included in

our global Operating Management System (OMS).

PERSONAL CONTROL methods are used by people to reduce inj uries, eliminate fatalities, and enable those people to

accomplish their tasks more effectively and take our company higher. Error analysis and consequence mitigation

techniques can be used to: 1) reduce the likelihood committing of errors, 2} trap incipient errors before they occur, and 3)

mitigate the consequences of errors after they occur.

The PERSONAL CONTROL techniques li sted below are rarely taught in operational organizations. But these methods

can be used to reduce injuries, prevent accidents, save lives, and increase production in high-risk businesoes.

ORGANIZATIONAL CONTROL

Operating Management System (OMS)

local Operating Management System (LOMS)

Managing Risk (Process Safety):

1. Identify Hazards

- 2. Assess Risk

- 3. Implement Cont rols

Process Safety Methods: There are many. Some examples are:

- Control of Work

Permitting Process, Job Safety Analysis, etc.

- Hazard Identification/Evaluation

HSSE Review, HAZID, MAHID (see MAHA), Process Hazard Analysis, Checklist, What If, Relative Ranking I

Risk Ranking, HAZOP , FMEA, Consequence Analysis , Fault Tree, Event Tree, Bow Tie Analysis, Human

Reliability Analysis, Task Hazard Assessment , Safety Evaluation and Task Assessment, etc.

- Risk Assessment

Risk Matrix, LOPA, Facility Siting, Fault Tree, Event Tree, MAHA, MAR, QRA, ALERT, Cost Benefit Analysis,

etc.

Programs to create Foresight (to anticipate risk} and Error \Msdom (to mitigate consequences}

Intelligent Wariness, Chronic Unease, Constant Vigilance

Support of Top and Middle Managers

- Respect of Hazards:

Mental skills developed and honed to identify hazards

Error Defenses. There are six defenses that can be used to reduce the consequences (and number} of errors, in

decreasing order of effectiveness and cost, in the organization.

1. System Design (Hard defenses}

1. Design Out: An example of effective mitigation this is the design incompatibility between the nitrogen

hoses and the oxygen inlets in a hospital. Since they don't fit together, human operators can't make the

fatal mistake of connecting a nitrogen supply to a breathing system.

2. Engineer In: Redundancy or interlocks are sometimes engineered into a system to make it difficult to

commit an unintentional mistake.

3. Guard Against Physical fences around dangerous hardware are intended to keep people away and

reduce the potential for injuries.

- 2. Rules, Procedures (Soft defenses)

4. Warning: Visual or aural alarms in a system will alert the human operators before a mistake is made.

5. Traininq Rules are established to reduce errors. Training is required to reinforce these rules.

6. Constraints + Affordances (Human Factors designs, e.g., push panels on doors)

{ FILENAME }

CONFIDENTIAL BP-HZN-BL Y 0 0 0 9 2 1 7 ~

PERSONAb-CONTROL

(listed in order of importance, as assessed by !he auihor)

1. Managing Risk (Personal Safety):

1. Identify Hazards (Conscious decision; requires skill)

- 2. Assess Risk

3. Implement Conirols (Reduce Exposure)

Injuries commonly occur after fail ing Ia identify hazards (step 1) or failing to implement sufficient controls (being risk-

iolerant or complacent (step 3).

2. Situational Awareness. This is one of !he most powerful operational iechniques used to reduce the consequences of

risk in hazardous situations in a high-risk industry. It may help to remember these techniques by thinking of them in terms

of past, present, and future.

A. Search for Vulnerabilities. (Past) The operator (or manager) must attempt to understand completely the

of the system that is being operated. Thi s includes the vulnerably, or weaknesses, of the

hardware, software. and people. Among the best ways to understand vulnerability is to research design

manuals, drawings, manufact urer reports and instructions, read lessons learned and historical incident reports,

talk to experienced operators. An operator should never operate any system fully understanding, to the

best of his or her ability, !he vulnerabilities of the system.

B. Maintain Awareness. (Present) [For more detailed explanation, see T-0 Thinking in the section, Mindfulness]

Through intensive tr aining and operational practice, humans can develop the ability to remain aware of the

hazards surrounding them. Identification of hazards is best accomplished with directed attention and conscious

thought processes. The techniques and skills required must be continually practiced.

The power of the mind is someti mes underestimated. Through directed effort of attention, with top-down,

executive-level cognition, pi loi s or operators can pre-condition their thought patterns to respond more effectively

to external stimuli . The classic example is the intensive training that astronauts receive in the simulators before

flight. Through a heightened state of awareness developed with extensive training, flight crew members can

work together as a team. with highly effective communications, to sense and respond quickly and correctly to

small changes in tiny gauges that indicate minor problems during the powered ascent phase of the rocket' s

launch. Or they can take proper corrective actions when a 500,000 lb-thrust main engine fails. The best crews

will diagnose and correct a problem before the mission computers have recognized and annunciated the failure

Similar mental training can be used to improve one's control over internal emotions. The brain has the ability to

train itself to prevent impulsive reacti ons in social situations, or reduce the possibility of emotional hijacking in a

stressful meeting when tempers flare.

C. Anticipate the Changing Shape of Risk. (Future) This is the most difficult of the three techniques, but it likely

represents the greatest potential to prevent accidents. Because are continuously changing, risk is

always changing. If an operator thinks he or she understands ri sk, he or she will be surprised (at best). injured or

killed (at worst). Operators must learn to recognize subtle differences in the operating environment, systems. or

any other inputs and at-ri sk situations, and then anticipate how the risk changes. This valuable ability to look into

the future to prevent accidents requires mastery of the social and human aspects of operational issues. in

addition to the technical aspects. Accurate prediction requires the social elements of communication,

relationship-building, judgment, intuition, experience, human values, human factors, decision-making, emotional

intelligence, with holi stic, systemic, non-linear thinking in a supported climate of organizational learning.

3. "Trigger Steps." (Prep Steps and Exec Steps). Preparatory Steps have little or no consequences. "Trigger Steps"

(or Execute Steps) are different Because the best operators anticipate consequences, they treat Execute Steps

differently. Extra vigilance is warranted to ensure the conditions are right and errors have been eliminated before

executing steps that have consequences. The act of forgetting your keys only has consequence after you close the

locked door to your house. Understand that the act of closing the door has different significance than preparing to leave

your house as you think about your upcoming meeting. If you are conditioned to think about the consequences of your

Execute Step, you may think about your keys just before the door closes. Good pilots always think about their actions in

terms of the consequences. Before pushing the ignition button in the cockpit, the best pilots review one last time that they

have the set the proper configuration, including electrical power, and fuel flow, and that the external area is clear.

Regardless of their diligence in using the checklist, the elite pilots mentally check items one last time as they enter

the runway for takeoff. If they re-check their engine(s), lights, configuration, and controls, there will be fewer negative

consequences after takeoff. Summarizing, operators should develop the ability to identify "Execute" steps before

executing them. Just prior to "pulling the trigger," the operator should think of three things before an Exec Step (Trigger

Step): -

A (Past) -Is my configuration Lined up: Upstream I Downstream?

B. (Present)- Am I in the Line of Fire?

{ FILENAME }

CONFIDENTIAL

2

BP-HZN-BLY00092176

C. (Future) - What wi ll line," what is Expected AND Unexpected?

4. Protect Your Hardware. Hardware is determini stic. A specific component will fail for a reason. You can minimize the

chances of having component failures by treating your systems well and operating them within their design limit s.

Know the vulnerabilities of your hardware and do not push the red lines. If you take care of your hardware, it will take

care of you. [Include Walter Guiliot's examples- 2 VBRs. assess. if it turns the corner, Casing Shears, th en Blind

Shears, (protects the Blind seal)]

5. Assurance. Three types of assurance are used to reduce the consequences of errors.

A Verification. Thi s is the simplest method. Cross-checking is an exampl e of a veri fi cation method. An operator

can simply review the procedures after compl etion of a section to verify that the steps were executed correctly.

B. Redundant Verification. In the Control Room of a Refinery (or on the Space Shuttl e), some syst ems have

redundant sensors to indicat e the position of a valve or the speed of a motor. The output of the sensor may be

sent to two different types of readouts, for example, a hard-wired mechanical gage and a cathode ray tube

monitor. This is a redundant method for cross-checking the position of the valve. Using two crew members to

compl ete a procedure can be considered a redundant method of verifying, or cross-checking, the accuracy of

the process.

C. Dissimilar Verification. A much more powerful method of assurance involves Dissimilar Verification. When a

valve in a gas line is opened, redundant sensors may indicate the actual position of the valve. But if the operator

has access to a different kind of sensor, sucb_as the pressure sensor downstream from the opened valve, using

both the local position sensor and the remote pressure sensor provides greater assurance that t he system is

working correctly. This assurance met hod invol ves Dissimilar Verification of the function. Similarly, if an

Operator has completed a procedure, a simple review of the procedure may lead to the same erroneous mental

process that led to misreading or missing a step. If the Operator uses a di ssimilar method of verification. such as

looking for symmetry in the resultant switch positions, an error may be ident ified before consequence occurs.

Another example is the simple task of adding a string of numbers. Verifying the result by adding the numbers a

second time, but in reverse order, may prevent the same error from being made twice.

6. Error-Correction Techniques. After performing an analysis of errors, the best operators identify techniques that can

be used effectively to eliminate errors in a particular task or reduce their likelihood of occurring. Knowing that all humans

have the possi bility of making errors in general , the elite operators strive to develop and use techniques to trap incipient

errors or mitigate the consequence of any errors that have occurred in all phases of operations. Summarizing, operators

should develop and use Error Correction Techni ques during processes and before consequences to:

A Reduce likelihood of errors (Past)

B. Trap incipient errors before they occur (Pres)

C. Mitigate the consequences of errors (Future)

7. Maintain Positive Control (when moving objects). Operators must maintain continuous control of the position and

velocity of objects when moving them. This requires Control and Connection.

A Control. Never relinquish control when moving objects. Operators must have a method to regulat e the position

and velocity (speed and direction) of objects. When using a control system, operators must understand the

normal modes of operation, including the automated and augmented functions used to command motion of

obj ects. If the system causes undesired motion, the operator must be able to override the system and

compensate quickly and accurately. Operators must also understand the degraded modes of operation of the

control system and have an effective plan to retain positive control when failures occur. Control must be

maintained when moving objects mechanically using forklifts, backhoes, trucks. cranes, or manually using hands

or feet. Intentionally releasing an object (dropping to a lower level) relinqui shes control and should be avoided.

Pushing an object without the ability to pull does not afford complete control.

B. Connection. Positive control requires a physical or mechanical connection between the object being moved and

the system being used to cause motion. This positive connection provides sufficient ability to stop the motion or

change direction to prevent undesired collisions with other objects. Simply stated, the load must be "secured"

before attempting to move it. Do not push, pull, or drop anything without the ability to control the motion.

8. Prevent Undesired Collisions.

A. Maintain Accurate Knowledge of the Control System and its State Vector. The operator must always understand

the system being used to control the motion of an including potenti al failure modes, and the motion of the

object being controlled (its State Vector). Failing to understand the control system may resuK in losing control

with undesired collisions. Failing to understand the motion of the object may result in incorrect control inputs and

undesired collisions.

B. Maintain Accurate Knowledge of Local Environment. The operator must understand the environment around the

object being moved under control . Failing to understand what other objects are near the object being moved

{ FILENAME } 3

CONFIDENTIAL BP-HZN-BLY00092177

may- resuH--in- undesiFed-sellisions. An undesired- collision...may_o.ccur....wben. an operator continues to back up

without being able to see the environment behind the vehicle accurately and compl etely. Wing-walkers or

spotters are used when drivers cannot see the local environment around the vehicle.

C. Anticipate Potential Conflicts or Collisions. When controlling a car or truck in an environment with other moving

vehicles or objects, the operator (driver) must be able to predict the motion of all the other objects. The skill

required to integrate the entire scene or environment and avoid potential conflicts or collisions must be

practiced. Operators who control moving objects must develop and demonstrate capability, through a

qualification program, and maintain proficiency (intense competence) through a recurrent program of practice or

operations.

D. Assume the Worst. To avoid collisions or accidents when moving objects, always assume the worst. When

driving a car on a winding road, assume there is an obstacle just out of sight around the comer. Do not drive

faster than you can see and respond. In other words, preserve the ability to avoid obstacles that suddenly

appear in your path of motion. Assume other drivers will run red lights or stop signs. Drive in such a way to avoid

them when they do. Assume your control system with fail at the worst time, anticipate the consequences of the

failure, and use a plan of operations that preserves options to maintain control of the object. When using any

system with augmentation or automated modes of operation, anticipate what will happen when the

augmentation or automated system defaults to a degraded mode of operation. Have a plan to reduce the

of these failures if they occur at the worst possible time during operations.

9. Error Analyses (Individual and Group). A personal analysis of errors committed is an effective way to determine

corrective actions needed to reduce errors. Highly introspective, honest, self-critical evaluations are the most effective.

Analyses of the error patterns that an individual or group of operators have historically made can indicate creative

solutions to help people reduce the amount of errors committed.

10. Assess Danger (Exposure). The first step in managing risk is to identify the hazard. This is a skill that must be

developed and practiced. In the field, identification of hazards requires active, directed attention and conscious effort.

Most injuries and fatalities occur when people either fail to identify the hazard or exhibit risk-tolerance (accept the risk

without controlling the hazard, or become complacent). The organization must provide training to help people identify the

hazards, but the individuals must practice and use this skill to assessing the danger.

11. Preserve Options (AHernate Paths, Divert Fields, Escape Trajectories). Never eliminate the last option. Predict the

next failure, and devise a plan to accommodate it. Pilots always have a divert plan in case the weather degrades. In a

car, the mistake was not in hitting a deer around a curve at night; the error was in driving at a speed that eliminated the

option to stop or avoid the impact.

12. Increase Margins (from Danger). This is similar to managing Margins of Safety. But there is a subtle difference that

is worth considering when operating so close to the edge of danger. Generally in low-risk operations, the Margins of

Safety are wide enough that they can be managed with limited attention. As the operational conditions degrade and risks

increase, the safety margins are effectively reduced. But in these low..risk operations, sufficient Margins of Safety still

exist, so changes to operational procedures are not required. Managers who work with low risk usually are not required

to conduct continual assessments of the risks or modify their decisions or strategies often. But in high-risk operations, the

Margins of Safety are so narrow that it is better to think of them as "Margins from Danger." Because these margins are so

low, continual assessments are required. When operational conditions invariably change, the margins can become

negative. Operators and managers involved in high-risk operations must continually be aware of these shifting Margins

from Danger. To stay alive, they must constantly make adjustments in their operating environment to maintain positive

Margins from Danger. An example of this kind of management is experienced by every driver who operates a motor

vehicle on the roads. The best drivers will not have a collision on the highways, and they operate their vehicles with

nearly constant attention to the dangers around them. They drive in a way to maximize their margins from danger.

13. Communication Verification. Pilots who have any doubt about what the controller said will verify the information.

Even when there is no doubt in the mind of a single operator, it is good practice to use terminology that clearly el iminates

doubt or confusion in the other person's mind. Reading back pertinent infomnation between the pilot and the controller is

a method of verifying communication. On nearly every flight, an instance of confusing or misleading communication

involving improper temninology can be heard between pilots and controllers. Research has shown that on four of every

five airline flights, an error is made. Often the error involves miscommunication.

14. Assessment of Competence. The leaders in the organization must implement an effective process for assessing

the competency of operators. This is critical in high-risk businesses. Competency assessment is the final part of the initial

program of qualification to do a job, and is conducted after building capability through training and practical experience.

Competency assessment is also the final part of a recertification process, which is a continuous program of building

proficiency, or deep capability. In the assessment of competence (for the initial qualification and the periodic re-

certification), knowledge and attitude are assessed, but the primary source of evidence must be the performance of

competency- the operator must demonstrate the necessary practical skills. These skills must be performed to specific

{FILENAME } 4

CONFIDENTIAL BP-HZN-BL Y00092178

standards-tJnder-specific-conditiens-to-Feeeive-a-ter:tification to-operate in the role, or a re-certification to continue in the

role.

And on the level of personal control, operators must continuously assess the competence of their teammates by using an

informal process of assessment. When crew members correctly assess the competence of their teammates, they can

more accurately trap the errors that are made by the teammate. If a crew member fails to assess the weakness of a

teammate, or if the assessing crew member incorrectly assumes the teammate will be error-free, that assessing crew

member may miss opportunities to heiJ:rlhe-assessed teammate prevent errors.

15. Divergence Recognition. Crew members and operators who have developed an abilrty to recognize a divergent or

deteriorating situation have the greatest chance of averting disaster. Divergence Recognition enables an awareness of

error-prone rushing during a procedure, minor failures in a system, distractions, fatigue, and stress in other crew

members. Cognitive lock, or tunnel vision, is a debilitating reduction in the normal mental processes of pilots in

operations under stress or confusion. With experience and proper training to recognize diverging or distracting situations,

cognttive lock is much less likely to occur.

Distractions were one of the greatest causes of errors during T-38 aircraft operations at NASA. The key to reducing the

negative effects of distractions is to recognize the diverging situation. Distractions can be caused by normal

conversaUon. Any interrupUons, which demand new thoughts or actions, in the course of completing a checklist or

procedure are a potential source of distractions. A pilot can be experiencing Local Preoccupation with a complex

procedure, 2 single confusing or critical step in a checklist, a salient event, or a sudden malfunction in a system. Finally,

the operator may be experiencing Global Preoccupation with a personal situation or a family or external issue. During

every critical phase of flight on all six of my space mission, we experienced potential distractions. Successfully

recognizing these distractions was the first step in preventing degradation in our perfonnnance.

16. Mental Preparation. The discipline that we used in accomplishing these items contributed to our success during the

STS-113 mission. We were always looking ahead and staying mentally prepared for future events in flight.

17. Methods to Aid Weak Prospective Memory. Knowing that humans typically have weak Prospective Memory (the

ability to remember items in the future with no external alanms or reminders), we used a method to combat distractions.

On regular intervals before important and time-critical events, we would announce the impending event. If a maneuver or

a cool-down procedure was to start several minutes in the future, we would announce the "time-to-go each minute

before the event.

18. Assertiveness To Authority. Many airplanes have flown into the ground because subservient co-pilots were

reluctant to question the decisions or actions of domineering senior pilots. Elite leaders welcome dissenting and

challenging opinions, because the added analyses will make the results stronger in the decision-making process.

19. Mindfulness. Operators use mental discipline and employ the "three Ts" - Technical Knowledge, Team

Effectiveness, and T-0 Thinking - plus "Degrees of Vision" and "Balancing Confidence with Humility' to enhance

mindfulness.

Technical Knowledge is mandatory. Operators should know everything they can about the system they

manage. With superior technical knowledge, operators can reduce the consequences of errors and prevent

accidents.

Team Effectiveness starts with an honest understanding of personal strengths and weaknesses. The elite

operators perfonm analyses of their personal error tendencies and develop mitigation strategies to minimize the

consequences of personal errors. They also are intimately familiar with the strengths and weaknesses of their

teammates. The best teams are populated with the best operators who know how to work effectively with each

other and understand how to achieve the best results by developing the most effective methods for working

together.

T-0 Thinking is used by astronauts at liftoff. (The countdown clock is anchored at time 'T minus Zero seconds",

which occurs at the moment of Solid Rocket Booster ignition.) Elite operators in the petrochemical industry stay

in the moment. During the dangerous and dynamic phases of high-risk operations where things happen quickly

and minor failures can cascade to catastrophe, the best operators do not worry about anything outside ten

seconds from the present. Nothing else matters past this temporal horizon. Because they have greater mental

clarity in the present, they have the ability to sense everything, assess all possible situations, make effective

decisions, and correctly respond to any emergency. If a pilot can develop greater mental clarity under 7.5 million

pounds of thrust, he or she will be an effective astronaut Fear is a useful emotion that can motivate a person to

study, practice, and prepare for high-risk operations. Worry is unproductive fear and a consuming emotion

where nothing is done to eliminate it. Long before the pressure of danger builds, worry must be eradicated and

fear must be channeled toward preparation. During high-risk operations, fear must be managed and repressed

{ FILENAME } 5

CONFIDENTIAL BP-HZN-BLY00092179

through active volition and cognitive discipline. -AII -of-this- can- only- be accomplished_ thwugh intensive and

directed training and mental preparation.

Degrees of Vision. Since operators usually are constrained to work with the systems they are given and have

limited opportunities for redesign, personal mental discipline can be the most powerful method for reducing

errors and staying safe. The "degrees of vision" that an operator senses can be changed mindfully to suit the

challenging conditions of the current operational situation. During critical tasks, focused attention may be

warranted. In dynamically changing situations, it may be best to have a wider perspective to be able to sense

more. The ability to concentrate is critically valuable in both cases. Training can help the operators know when

to focus on the complex tasks at hand, and when to open mental awareness and maintain a wider field of

attention to prevent accidents.

Balance High Confidence with Healthy Self-doubt. To be effective in high-risk environments, operators (and

managers) must be highly confident. This comes from training and preparation. But this confidence must be

balanced with the humility of healthy self-doubt. The difference is, "I know I am capable of operating successfully

today, but am I operating successfully right now?" Without confidence, operators will make many mistakes.

Without humility, operators will never realize they are making mistakes. Before critical operations, good

operators ask themselves, "What have we missed?", "What have we failed to do?", "What mistakes have we

made that we can correct before it's too late?"

20. Selecting Mental Processes (Controlled and Automatic). Through an understanding of two different mental

processes, we can operate more effectively. The brain can be trained to use a high-level cognitive process of

concentrating on a single challenging task, such as driving on a dangerous highway, to prevent an accident. A second

kind of mental process can be used to perform several tasks simultaneously. Pilots use this lower-level mental process

when they are flying their airplane through a thunderstorm at night, with low fuel, while responding to an Air Traffic

Controller in the tower to acknowledge the clearance, and simultaneously remembering to lower the landing gear while

the Master Alarm light- indicating a systems emergency- inconveniently distracts the crew members.

These two kinds of cognitive processes are called Controlled and Automatic. We are mostly aware of the upper-level

executive Controlled process, as that is what we are concentrating on or thinking about at any given time. But most of the

brain's processing is accomplished in the lower-level Automatic mode. We rarely think about how to navigate to a

refrigerator or open its door (Automatic processing), but we do think about what food we want that is inside (Controlled

processing). Using the appropriate mode in specific situations can save lives. Dangerously, many drivers are operating

their cars around you while using only their lower-level Automatic mental processing, rather than their Controlled mode of

conscious thinking, with rts increased ability to sense the weak signals of an impending accident.

Although highly capable and powerfully effective in novel situations, the Controlled mode of thinking can handle only one

task at a time. To conduct multiple tasks at the same time (multi-task), we must use our lower-level Automatic

processing. Extensive training enables more and more tasks to be processed by our Automatic .mode. The same training

enhances our ability to switch rapidly between separate tasks that are controlled sequentially in Controlled mode. The

result of more tasks in Automatic and quicker switching between the serial tasks in Controlled, gives us the illusion of

multi-tasking. We're really controlling only one task at a time, with all the others on Automatic. But this is an effective way

to operate, and rt is why pilots and athletes train so much. During flight operations, astronauts and pilots relegate more

and more tasks to their Automatic processing to accomplish simultaneous complex tasks successfully. This is only

mastered after intensive training in progressively more demanding situations.

But the Automatic processing mode has limitations. When operating in Automatic, we have little ability to respond to

unforeseen or untrained srtuations. Also, although our brain's response time (our reaction time) is quick, the response is

only triggered if an external stimulus grows large enough to penetrate our senses. If a driver is operating "on autopilot,"

the initially weak signals of an impending car accident may not be sensed until it is too late to prevent the accident. This

is why we should not drive while using a cell phone. While on the phone, the brain is using its adaptable, highly sensing

Controlled mode exclusively for the conversation. With increased danger, the driving tasks are relegated to the lower-

level Automatic mode of processing. Total response time may be lost, since the Automatic mode has limited. ability to

sense weak signals. That precious second of lost time may be the last second our brain ever experiences. When we

drive a car, we should drive in the Controlled mode of mental processing. We should concentrate on the dynamically

changing situation and use our heightened ability to sense weak signals required to prevent accidents.

If we want to stay alive, when driving we should think about driving. When board operators are lifting gas, they should

concentrate on the lifting process. When field operators are in a high-risk environment, they should concentrate on

identifying hazards. Know when to stay in the moment. Know how to stay in the moment using the disciplined mental

processes ofthe Controlled mode of cognition.

21. Challenge Your Mental Model. When flying, the best pilots challenge their existing mental model of their current

state. They cross-check their instruments, and verify their navigation. Good pilots are always thinking about what they

might be missing or misinterpreting. They are attentive to the slightest indication that their mental model of the situation

{ FILENAME} 6

CONFIDENTIAL BP-HZN-BL Y00092180

might be wrong. It is far easier to flyinto;he--groundwhen-you-are-mistakenly-eoAfideAt- you-have...sufficient altrtude, than

if you routinely challenge your mental model.

22. Sharing Mental Model (with others). This was the most important and effective technique we used to eliminate

nearly all errors in flight. Before beginning every procedure, we reported to the Mission Control team the title of the

procedure and the page number of the Flight Data File document (checklist) we were using. We also made a short

transmission stating our intentions before every change in the Auto Pilot for flight control, maneuver execution,

operations sequence transition, water dump initiation, block number in the rendezvous procedures, and step number in

the robotic arm operations, or any action that could have negative consequences in the outcome of the mission. This

enabled the Mission Control teams to be more effective in their operations, and it helped us to eliminate nearly all

mistakes in flight.

23. Two-person Rule. Two people working together have a greater chance of trapping potential errors and completing a

procedure or task correctly than a single person working alone. Often space flight crews have a rule that all procedures

will be conducted by two crew members, if possible. But this Two-person Rule is often misapplied. When one crew

member is reading the checklist alone, and the other crew member is actuating the switches independently, there is only

one brain working on each phase of the operation. To comply with the Two-person Rule properly, both crew members

should be reading the checklist together, and both crew members should be watching the switch when the one crew

member actuates it. As another- example, this_buddy system can be successful in preventing accidents where a single

operator may forget te don fall protection before climbing.

24. "Telegraphing" actions. Before moving any switch or making command inputs to a controller, the best operators

indicate their intentions by pausing briefly over the switch or control to allow other crew members to verify the

correctness of the intended action.

25. Think Fast and Act Slowly. Through personal experience and learning from the mistakes of others, the best

operators have learned to think fast and act slowly. It takes a certain kind of person with specific mental skills to be

successful in fast-paced operations involving dynamic, constantly changing situations that can degrade to catastrophe

through inappropriate action or passive inaction. Good operators sense conditions, analyze options and decide solutions

quickly, but implement corrective actions deliberately. Speed is desired, but precision is required. It's best to be fast, yet

operators can't afford to be wrong. This is where people excel. The human mind surpasses the capabilities of computers

in judgment, intuition, and decision-making when given incomplete information. Solutions can be determined quickly by

people with experience. But we have the self-awareness to know we can make mistakes. And this is why we will always

need operators at the controls. It's the will to live that drives the ability of an elite operator to be accurate in the face of

danger. With years of experience and mentoring, the best learn to think fast, yet act slowly.

26. Cognizance of Personal Limitations. Before we launched on our STS-113 mission to the International Space

Station, each crew member knew the weaknesses of himself and the other team members. We kept a record of mistakes

that were made during training events. This enabled us to help each other and nearly eliminate all mistakes during flight

Self-imposed Procedural Limits. In space flight operations, we could sometimes accomplish parts of procedures

early, before the scheduled execution. An example of this was pre-setting the maneuver parameters using keyboard

entries which were displayed on cathode ray tubes before the time of the maneuver. Although we stayed farther

ahead mentally, and anticipated many steps into the future, we limited our actions (keyboard entries) to be only one

step ahead. This reduced our chances of making errors. We did not allow ourselves to attempt the complexities of

entering two or three different maneuvers at one time. We never became complacent or distracted, by entering too

many maneuvers into the Auto Pilot, which may have resulted in a missed or erroneous maneuver. This was a minor,

but effective, improvement in our operations.

27. Acknowledgment of Weakness (Specific). Admitting a personal weakness is a sign of maturity and confidence. It is

also one of the best ways to solicit help in reducing errors and preventing accidents.

28. Admission of Error. When the commission of an error is admitted quickly and candidly, corrective actions can be

taken to mitigate the consequences more effectively and completely.

29. Awareness of Vulnerability (General). Knowing when people and systems are vulnerable can create success

rather than tragedy. People in an organization are vulnerable during shift han dover or transitions. Operating systems are

more vulnerable during startup or when experiencing transient operations or mode changes. In the best organizations,

operators will increase their vigilance at these times to prevent accidents.

30. Desire to Improve (Receive and Give Help). This was a highly effective technique for us to minimize mistakes

during the ST&-113 mission in low earth orbit There were many times during mission when the individual crew members

could have acted alone, without assistance from the ground teams or other crew members. But because we honored the

simple desire to have help with procedures, no matter how small or unimportant, we were able to minimize our mistakes.

{ FILENAME } 7

CONFIDENTIAL BP-HZN-BLY00092181

Though- having- a-eesire-to-receive-help.-does--not..sound profo.und,_wheo_all crew members satisfied this genuine desire,

the beneficial results were significant Nearly all errors were prevented during the complex, two-week long mission_

Jim Wetherbee

BP

{ FILENAME }

CONFIDENTIAL

8

BP-HZN-BLY00092182

- TECHNIQUES (Outline)

Organizational Control

Operating Management System (OMS)

Local Operating Management System ILOMSl

Managing Risk (Process Safety):

1-:- ldentify Hazards

2. Assess Risk

3. Implement Controls

Process Safely methods:

Control of Work

Permitting Process, Job Safety Analysis, etc.

Hazard Identification/Evaluation

HSSE Review, HAZID, MAHID (see MAHA), Process

Hazard Analysis, Checklist, What If, Relative Ranking I

Risk Ranking, HAZOP, FMEA , Consequence Analysis,

Fault Tree, Event Tree, Bowne Analysis, Human

Reliability Analysis, Task Hazard Assessment, Safely

E.valuation and Task Assessment, etc.

Risk Assessment

Risk Matrix, LOPA, Facility Siting, Fault Tree, Event

Tree, MAHA, MAR, QRA, ALERT, Cost Benefit Analysis,

etc.

Safety Programs to create Foresight and Error Wisdom-

lntelligenl Wariness, Chronic Unease, Constant Vigilance

Leadership Support of Top and Mid Mgrs- Respect of

Hazards; Develop and Maintain Mental skills

1. Human Factors (Hard defenses)

Design out (02/N2),

Engineer in (Redundancy, Interlocks),

Guard against (Fences)

2. Rules, Proced (Soft defenses)

Warning (Alarms, Signs)

Training (Rules, Regulations)

Constraints+ Affordances

Personal Control

1. Managing Risk (Personal Safety):

1. Identify Hazards (Conscious decision; req's skill)

2. Assess Risk

3. Implement Controls (Reduce E.xposurel

2. Situational Awareness

1. (Past)- Search for Vulnerabilities (SE airplane; room wl

1 exit; Bahrain (Mar 06); WTC; Neg Press Test]

2. (Present) Maintain Awareness [Hand, back inj.]

3. (Future)- Anticipate the Changing Shape of Risk

[Welding in cold wx)

Notice small changes

+ The power of Negative Thinking

3. Trigger Steps (Consequence)

(Past)- Lined up: Upstream I Downstream

(Present) - Line of Fire

(Future)- Down the line; E.xpected I Unexpected

4. Protect Your Hardware Waller Guillot ex- 2 VBRs,

assess, if il turns the corner, Casing Shears, then Blind

Shears; (protects the Blind seal}

5. Assurance- 1. Verification

2. Redundant Verification

3. Dissimilar Verification

6. Error Correction Techniques- Used During Process and

Before Consequences to:

1. Reduce likelihood of errors (Past}

2. Trap incipient errors before they occur (Pres)

3. Mitigate the consequences of errors (Future)

7. Maintain Positive Control (when moving objects)

A. Control- Never relinquish control. Retain control of

position and velocity; Understand normal automated and

{ FILENAME }

CONFIDENTIAL

augmented functions, degraded modes; (Override

system, compensate quickly and accurately)

B. Connection- Ensure load is Secure with physical or

mechanical connection (to prevent undesired collisions)

8. Prevent Undesired Collisions.

Maintain accurate knowledge of:

1. State vector and control

2. Local environment

Anticipate potential connicts or collisions;

Assume the worst

Never overdrive your vision (Never drive faster than you

can see and respon(j)

9. Error Analysis (Personal , Group)

Embrace learning from mistakes; Value feedback

10. Assess Danger (Exposure)

11. Preserve Options (An, Dlv, ET) [-Chain bucket timing]

12. Increase Margins (from Danger)

13. Communication Verification

14. Assessment of Competence

15. Divergence Recognition

!I in Scope; Hurrying

Unexpected Event I Situation

Abnormal Situation, Minor Failure

Distraction Mitigation, Management

Fatigue; Stress Recognition

16. Mental Preparation

17. Methods to aid weak Prospective Memory

111. Assertiveness (to Authority)

19. Mindfulness

+ Degrees of Vision (Wide, Focus)

+ High Confidence I Healthy Self-Doubt

Technical Knowledge

Team Effectiveness (Self, Others}

T -0 Thinking

- Intense Concentration

In the Moment (Temporal Horizon= 10 sec)

20. Selecting Mental Processes- Controlled, Automatic

21. Challenge Mental Model- Self;

Use different mental process;

Encourage questioning; Use non-experts

22. Sharing mental model (wl Board Operators, Central

Control Room)

23. Two-person rule

24. "Telegraph' actions

25. Think Fast, Act Slow

Slow down to Speed up

Multitasking is a myth

Never act impulsively

26. Personal Limitations cognizance

Self-imposed procedural limit

27. Acknowledgment of Weakness (Specific)

28. Admission of Error

29. Awareness of Vulnerability (General)

30. Desire to Improve (Receive, Give help)

9

BP-HZN-BLY00092183

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- BP's Post-Trial BriefDocumento72 pagineBP's Post-Trial BriefOSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- USAs Proposed Findings Phase I (Doc. 10460 - 6.21.2013)Documento121 pagineUSAs Proposed Findings Phase I (Doc. 10460 - 6.21.2013)OSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- BP's Proposed Findings - Combined FileDocumento1.303 pagineBP's Proposed Findings - Combined FileOSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- To's Proposed FOF and COLDocumento326 pagineTo's Proposed FOF and COLOSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- HESI's Proposed FOF and COLDocumento335 pagineHESI's Proposed FOF and COLOSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Macondo Bod (Basis of Design)Documento23 pagineMacondo Bod (Basis of Design)OSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Plaintiffs Proposed Findings and Conclusions (Phase One) (Doc 10459) 6-21-2013Documento199 paginePlaintiffs Proposed Findings and Conclusions (Phase One) (Doc 10459) 6-21-2013OSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Laboratory Results Cement Program Material Transfer TicketDocumento13 pagineLaboratory Results Cement Program Material Transfer TicketOSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- PSC Post-Trial Brief (Phase One) (Doc 10458) 6-21-2013Documento72 paginePSC Post-Trial Brief (Phase One) (Doc 10458) 6-21-2013OSDocs2012100% (1)

- Foam Stability Testing: Request Date Slurry I.D. Result CommentsDocumento1 paginaFoam Stability Testing: Request Date Slurry I.D. Result CommentsOSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Exterior: Circa 2003Documento1 paginaExterior: Circa 2003OSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Circa 2003Documento1 paginaCirca 2003OSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Driller HITEC Display CCTV Camera System: Source: TREX 4248 8153Documento1 paginaDriller HITEC Display CCTV Camera System: Source: TREX 4248 8153OSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- DR Gene: CloggedDocumento1 paginaDR Gene: CloggedOSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Arnaud Bobillier Email: June 17, 2010: "I See Some Similarities With What Happened On The Horizon"Documento5 pagineArnaud Bobillier Email: June 17, 2010: "I See Some Similarities With What Happened On The Horizon"OSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Production Interval: 14.1-14.2 PPG M57B Gas Brine GasDocumento1 paginaProduction Interval: 14.1-14.2 PPG M57B Gas Brine GasOSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- April 20, BLOWOUT: BP Misreads Logs Does Not IdentifyDocumento22 pagineApril 20, BLOWOUT: BP Misreads Logs Does Not IdentifyOSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Webster:: Trial Transcript at 3975:2-4Documento1 paginaWebster:: Trial Transcript at 3975:2-4OSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Thrusters: Propulsion (PROP)Documento1 paginaThrusters: Propulsion (PROP)OSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- End of Transmission: Transocean Drill Crew Turned The Pumps Off To InvestigateDocumento1 paginaEnd of Transmission: Transocean Drill Crew Turned The Pumps Off To InvestigateOSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Major DWH Maintenance Timeline: April 20, 2010 Rig in ServiceDocumento7 pagineMajor DWH Maintenance Timeline: April 20, 2010 Rig in ServiceOSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Transocean 2009 Annual Report: D6732 Source: TREX-5649Documento3 pagineTransocean 2009 Annual Report: D6732 Source: TREX-5649OSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Engines: Electrical Power Generation (ELPG) Emergency Shutdown System (ESD)Documento1 paginaEngines: Electrical Power Generation (ELPG) Emergency Shutdown System (ESD)OSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Webster:: Trial Transcript at 4136:17-18Documento1 paginaWebster:: Trial Transcript at 4136:17-18OSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Webster:: Trial Transcript at 4015:14-16Documento1 paginaWebster:: Trial Transcript at 4015:14-16OSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- BP Is The OperatorDocumento1 paginaBP Is The OperatorOSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lloyd's Report - Appendix C: Deepwater Horizon Summary ReportDocumento1 paginaLloyd's Report - Appendix C: Deepwater Horizon Summary ReportOSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

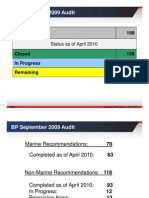

- BP September 2009 Audit: Total Items 188Documento3 pagineBP September 2009 Audit: Total Items 188OSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Systems On Deepwater Horizon: Source: TREX-30014, 30015 D6753Documento1 paginaSystems On Deepwater Horizon: Source: TREX-30014, 30015 D6753OSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Time Out For Safety Think Start: D6731 Source: TREX-4942Documento1 paginaTime Out For Safety Think Start: D6731 Source: TREX-4942OSDocs2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5795)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Volunteer Manual Catholic Community Services of Western WashingtonDocumento42 pagineVolunteer Manual Catholic Community Services of Western WashingtonmpriceatccusaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Student Will Revise Their Output From YesterdayDocumento4 pagineThe Student Will Revise Their Output From Yesterdayjeson galgoNessuna valutazione finora

- Thomas Hardy and PessimismDocumento19 pagineThomas Hardy and PessimismMartyn SmithNessuna valutazione finora

- American Revolution Brochure PDocumento3 pagineAmerican Revolution Brochure Papi-343567850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ship Stability Center of Gravity and Center of BuoyancyDocumento8 pagineShip Stability Center of Gravity and Center of BuoyancyAmin Al QawasmehNessuna valutazione finora

- 12 - Pauline Ethics - Paulinian StewardshipDocumento5 pagine12 - Pauline Ethics - Paulinian StewardshipJinky Bago AcapuyanNessuna valutazione finora

- Inflection 1. Inflection 1. Inflection 1. InflectionDocumento23 pagineInflection 1. Inflection 1. Inflection 1. InflectionOpa YatNessuna valutazione finora

- Biblical HermeneuticsDocumento5 pagineBiblical HermeneuticsLem SuantakNessuna valutazione finora

- PTO2 Reflection Rolando EspinozaDocumento3 paginePTO2 Reflection Rolando Espinozaleonel gavilanesNessuna valutazione finora

- Banham This Is TomorrowDocumento3 pagineBanham This Is Tomorrowadrip01Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2014 FoundationDocumento84 pagine2014 FoundationTerry ChoiNessuna valutazione finora

- Part 1 Fall 2018 Synthesis Matrix Analysis of LiteratureDocumento38 paginePart 1 Fall 2018 Synthesis Matrix Analysis of Literatureapi-437184486Nessuna valutazione finora

- Object Oriented ABAP GuideDocumento40 pagineObject Oriented ABAP Guidenavabhatt100% (3)

- Benedetto Croce, GoetheDocumento248 pagineBenedetto Croce, Goethemaivin2100% (1)

- Assessment Draft - Indra GunawanDocumento2 pagineAssessment Draft - Indra Gunawanpeserta23 HamidNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 IBM Quality Focus On Business Process PDFDocumento10 pagine1 IBM Quality Focus On Business Process PDFArturo RoldanNessuna valutazione finora

- New LTTS - AR 2019 - 18 04 2019 - 0 PDFDocumento37 pagineNew LTTS - AR 2019 - 18 04 2019 - 0 PDFprasanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mse 600Documento99 pagineMse 600Nico GeotinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Degenne, Forsé, 1999 - Introducing Social NetworksDocumento257 pagineDegenne, Forsé, 1999 - Introducing Social NetworksGabriel Cabral BernardoNessuna valutazione finora

- Leeka Kheifets PrincipleDocumento6 pagineLeeka Kheifets PrincipleAlexandreau del FierroNessuna valutazione finora

- KTC Employee Orientation (Jan.15.2020)Documento8 pagineKTC Employee Orientation (Jan.15.2020)Kirby C. LoberizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Methods Social PsychologyDocumento45 pagineMethods Social PsychologyElena Catalina MocanuNessuna valutazione finora

- In Defense of Globalization: Jagdish BhagwatiDocumento25 pagineIn Defense of Globalization: Jagdish BhagwatiSatyajit RanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan Biograph1Documento3 pagineSarvepalli Radhakrishnan Biograph1Tanveer SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study Thank You For Smoking 1Documento3 pagineCase Study Thank You For Smoking 1api-419017133Nessuna valutazione finora

- Psychoanalytic Literary Criticism On The Corpse of Anna FritzDocumento1 paginaPsychoanalytic Literary Criticism On The Corpse of Anna FritzJulius AlcantaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Miss Evers BoysDocumento5 pagineMiss Evers BoysMandy Pandy GNessuna valutazione finora

- Come Boldly SampleDocumento21 pagineCome Boldly SampleNavPressNessuna valutazione finora

- 2016-2017 Teaching Reflection Growth Mindset in High School ChorusDocumento2 pagine2016-2017 Teaching Reflection Growth Mindset in High School Chorusapi-266155292Nessuna valutazione finora

- Adding Similar Fractions Lesson PLanDocumento6 pagineAdding Similar Fractions Lesson PLanWize Dee86% (14)