Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

Caricato da

Arik DelacruzDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

Caricato da

Arik DelacruzCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/864208-overview

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

Author: John E McClay, MD; Chief Editor: Arlen D Meyers, MD, MBA more... Updated: Dec 6, 2011

Background

Subglottic stenosis (SGS) is a narrowing of the subglottic airway, which is housed in the cricoid cartilage. The image below shows an intraoperative endoscopic view of a normal subglottis.

Intraoperative endoscopic view of a normal subglottis

The subglottic airway is the narrowest area of the airway, since it is a complete, nonexpandable, and nonpliable ring, unlike the trachea, which has a posterior membranous section, and the larynx, which has a posterior muscular section. The term subglottic stenosis (SGS) implies a narrowing that is created or acquired, although the term is applied to both congenital lesions of the cricoid ring and acquired subglottic stenosis (SGS). See the images below.

Grade III subglottic stenosis in an 18-year-old patient following a motor vehicle accident. The true vocal cords are seen in the foreground. Subglottic stenosis is seen in the center of the picture.

Endoscopic view of the true vocal cords in the foreground and the elliptical congenital subglottic stenosis (SGS) in the center of

1 of 16

2/6/2012 12:14 AM

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/864208-overview

the picture.

Subglottic view of very mild congenital subglottic stenosis. Laterally, the area looks only slightly narrow. When endotracheal tubes were used to determine its size, it was found to be 30% narrowed.

Subglottic view of congenital elliptical subglottic stenosis.

Granular subglottic stenosis in a 3-month-old infant that was born premature, weighing 800 g. The area is still granular following cricoid split. This patient required tracheotomy and eventual reconstruction at age 3 years. True vocal cords are shown in the foreground (slightly blurry).

Intraoperative laryngeal view of the true vocal cords of a 9-year-old boy. Under the vocal cords, a subglottic stenosis can be seen.

2 of 16

2/6/2012 12:14 AM

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/864208-overview

This spiraling subglottic stenosis is not complete circumferentially. Laser therapy was the treatment choice and was successful after 2 laser treatments.

Continued lasering of the subglottic stenosis. The reflected red light is the aiming beam for the CO2 laser.

Postoperative view. Some mild residual posterior subglottic stenosis remains, but the child is asymptomatic and the airway is open overall.

Preoperative view of a 4-month-old infant with acquired grade III subglottic stenosis from intubation. Vocal cords are in the foreground.

A close-up view.

3 of 16

2/6/2012 12:14 AM

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/864208-overview

Postoperative view. The patient had been intubated for 1 week and extubated for 1 week.

A subglottic view following dilation with an endotracheal tube to lyse the thin web of scar and a short course (5-day) treatment with oral steroids.

Postoperative view of a 4-month-old infant with subglottic stenosis following cricoid split. Notice very mild recurrence of scaring at the site of previous scar. Overall, the airway is open and patent. The anterior superior area can be seen, with a small area of fibrosis where the cricoid split previously healed.

Preoperative subglottic view of a 2-year-old patient with congenital and acquired vertical subglottic stenosis.

History of the Procedure

Early in the 20th century, acquired subglottic stenosis (SGS) was usually related to trauma or infection from syphilis, tuberculosis, typhoid fever, or diphtheria. Also, children often had tracheotomies placed that caused laryngeal stenosis. In this era, attempted laryngeal dilation failed as a treatment for subglottic stenosis (SGS). Acquired subglottic stenosis (SGS) occurred increasingly in the late 1960s through the 1970s, after McDonald and Stocks (in 1965) introduced long-term intubation as a treatment method for neonates in need of prolonged ventilation for airway support. The increased incidence of subglottic stenosis (SGS) focused new attention on the pediatric larynx, and airway reconstruction and expansion techniques were developed.

Surgery without cartilage expansion

In 1971, Rethi and Rhan described a procedure for vertical division of the posterior lamina of the cricoid cartilage with Aboulker stent placement. A metal tracheotomy tube was attached to the Aboulker stent with wires, and the

4 of 16

2/6/2012 12:14 AM

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/864208-overview

anterior cartilaginous incision was closed. In 1974, Evanston and Todd described success with a castellated incision of the anterior cricoid cartilage and upper trachea, which was sewn open, and a stent made of a rolled silicone sheet was placed in it for 6 weeks. In 1980, Cotton and Seid described a procedure, in which tracheotomy is avoided, called the anterior cricoid split (ACS). The procedure was designed for use in neonates (usually, those born prematurely) with anterior glottic stenosis or SGS who had airway distress after extubation. The cricoid ring was divided anteriorly and a laryngofissure was created in an attempt to expand the airway without a tracheotomy. Holinger et al also described success with this procedure in 1987.

Surgery with cartilage-grafting reconstruction

In 1974, Fearon and Cotton described the successful use of cartilage grafts to enlarge the subglottic lumen in African green monkeys and in children with severe laryngotracheal stenosis.[1] All augmentation materials were evaluated, including thyroid cartilage, septal cartilage, auricular cartilage, costal cartilage, hyoid bone, and sternocleidomastoid myocutaneous flaps. After significant work, it appeared that costal cartilage grafts had the highest success rate. In the 1980s, Cotton reported his experience with laryngeal expansion with cartilage grafting. His success rates depended on degree of stenosis: More severe forms of stenosis required multiple surgical procedures. Cotton used the Aboulker stent. In 1991, Seid et al described a form of single-stage laryngotracheal reconstruction in which cartilage was placed anteriorly to expand the subglottis and upper trachea to avoid a tracheotomy.

[2] [3]

In 1992, Cotton et al described a 4-quadrant cricoid split, along with anterior and posterior grafting.

In 1993, Zalzal

[4]

reported 90% decannulation with any degree of subglottic stenosis (SGS) with his first surgical procedure. Zalzal customized the reconstruction on an individual basis, and most patients received Aboulker stents for stabilization.

Cricotracheal resection

In 1993, Monnier described partial cricotracheal resection with primary anastomoses for severe SGS, since grade III and grade IV SGS (ie, severe SGS) often requires multiple (3-4) surgical augmentations for decannulation. In 1997, Cotton described his experience with the procedure, reporting a decannulation rate higher than 90% for primary and rescue cricotracheal resection.

Problem

Subglottic stenosis (SGS) is narrowing of the subglottic lumen. Subglottic stenosis (SGS) can be acquired or congenital. Acquired subglottic stenosis (SGS) is caused by either infection or trauma, as seen in the images below. Congenital subglottic stenosis (SGS) has several abnormal shapes.

Grade III subglottic stenosis in an 18-year-old patient following a motor vehicle accident. The true vocal cords are seen in the foreground. Subglottic stenosis is seen in the center of the picture.

5 of 16

2/6/2012 12:14 AM

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/864208-overview

Granular subglottic stenosis in a 3-month-old infant that was born premature, weighing 800 g. The area is still granular following cricoid split. This patient required tracheotomy and eventual reconstruction at age 3 years. True vocal cords are shown in the foreground (slightly blurry).

Intraoperative laryngeal view of the true vocal cords of a 9-year-old boy. Under the vocal cords, a subglottic stenosis can be seen.

This spiraling subglottic stenosis is not complete circumferentially. Laser therapy was the treatment choice and was successful after 2 laser treatments.

Continued lasering of the subglottic stenosis. The reflected red light is the aiming beam for the CO2 laser.

Postoperative view. Some mild residual posterior subglottic stenosis remains, but the child is asymptomatic and the airway is open overall.

6 of 16

2/6/2012 12:14 AM

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/864208-overview

Preoperative view of a 4-month-old infant with acquired grade III subglottic stenosis from intubation. Vocal cords are in the foreground.

A close-up view.

Postoperative view. The patient had been intubated for 1 week and extubated for 1 week.

A subglottic view following dilation with an endotracheal tube to lyse the thin web of scar and a short course (5-day) treatment with oral steroids.

Postoperative view of a 4-month-old infant with subglottic stenosis following cricoid split. Notice very mild recurrence of scaring at the site of previous scar. Overall, the airway is open and patent. The anterior superior area can be seen, with a small area of fibrosis where the cricoid split previously healed.

7 of 16

2/6/2012 12:14 AM

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/864208-overview

Preoperative subglottic view of a 2-year-old patient with congenital and acquired vertical subglottic stenosis.

Holinger evaluated 29 pathological specimens obtained in children with congenital cricoid anomalies. Half of these children had an elliptical cricoid cartilage, as shown below, which Tucker first described in 1979.

Subglottic view of congenital elliptical subglottic stenosis.

Elliptical cricoid cartilage was the most commonly observed congenital abnormality. Other observed abnormalities included a flattened anterior shape, a thickened anterior cricoid, and a submucosal posterior laryngeal cleft.

Epidemiology

Frequency

The frequency of congenital subglottic stenosis (SGS) is unknown. The incidence of acquired subglottic stenosis (SGS) has greatly decreased over the past 40 years. In the late 1960s, when endotracheal intubation and long-term ventilation for premature infants began, the incidence of acquired subglottic stenosis (SGS) was as high as 24% in patients requiring such care. In the 1970s and 1980s, estimates of the incidence of subglottic stenosis (SGS) were 1-8%. In 1998, Choi reported that the incidence of subglottic stenosis (SGS) had remained constant at the Children's National Medical Center in Washington, DC; it was approximately 1-2% in children who had been treated in the neonatal ICU.[5] Walner recently reported that, among 504 neonates who were admitted to the level III ICU at the University of Chicago in 1997, 281 were intubated for an average of 11 days, and in no patient did subglottic stenosis (SGS) develop over a 3-year period. In 1996, a report from France also described no incidence of subglottic stenosis (SGS) in the neonatal population who underwent intubation with very small endotracheal tubes (ie, 2.5-mm internal diameter) in attempts to prevent trauma to the airway.

Etiology

The cause of congenital subglottic stenosis (SGS) is in utero malformation of the cricoid cartilage. The etiology of acquired subglottic stenosis (SGS) is related to trauma of the subglottic mucosa. Injury can be caused by infection or mechanical trauma, usually from endotracheal intubation but also from blunt, penetrating, or other trauma. Historically, acquired subglottic stenosis (SGS) has been related to infections such as tuberculosis and diphtheria. Over the past 40 years, the condition has typically been related to mechanical trauma. Factors implicated in the development of subglottic stenosis (SGS) include the size of the endotracheal tube relative to the child's larynx, the duration of intubation, the motion of the tube, and repeated intubations. Additional factors that affect wound healing include systemic illness, malnutrition, anemia, and hypoxia. Local bacterial infection may

8 of 16

2/6/2012 12:14 AM

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/864208-overview

play an important roll in the development of subglottic stenosis (SGS). Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) may play an adjuvant role in the development of subglottic stenosis (SGS) because it causes the subglottis to be continually bathed in acid, which irritates and inflames the area and prevents it from healing correctly. A systemic or gastrointestinal allergy may cause the airway to be more reactive, creating a greater chance of developing stenosis.

Pathophysiology

Acquired subglottic stenosis (SGS) is often caused by endotracheal intubation. Mechanical trauma from an endotracheal tube, as it passes through or remains for long periods in the narrowed neonatal and subglottic airway, can lead to mucosal edema and hyperemia. These conditions then can progress to pressure necrosis of the mucosa. These changes have been observed within a few hours of intubation and may progress to expose the perichondrium of the cricoid cartilage. Infection of the perichondrium can result in a subglottic scar. This series of events can be hastened if an oversized endotracheal tube is used. Always check for an air leak after placing an endotracheal tube because of the risk of necrosis of the mucosa, even in short surgical procedures. This practice is common among anesthesiologists. Usually, the pressure of the air leak should be less than 20 cm of water, so that no additional pressure necrosis occurs in the mucosa of the subglottis.

Presentation

History

Children with subglottic stenosis (SGS) have an airway obstruction that may manifest in several ways. In neonates, subglottic stenosis (SGS) may manifest as stridor and obstructive breathing after extubation that requires reintubation. At birth, intubation in most full-term neonates should be performed with a 3.5-mm pediatric endotracheal tube. If a smaller-than-appropriate endotracheal tube must be used, narrowing of the airway may be present, which could suggest subglottic stenosis (SGS). The stridor in subglottic stenosis (SGS) is usually biphasic. Biphasic stridor can be associated with glottic, subglottic, and upper tracheal lesions. Inspiratory stridor usually is associated with supraglottic lesions; expiratory stridor usually is associated with tracheal, bronchial, or pulmonary lesions. The level of airway obstruction varies depending on the type or degree of subglottic stenosis (SGS). In mild subglottic stenosis (SGS), only exercise-induced stridor or obstruction may be present. In severe subglottic stenosis (SGS), complete airway obstruction may be present and may require immediate surgical intervention. Depending on the severity, subglottic stenosis (SGS) can cause patients to have decreased subglottic pressure and a hoarse or a weak voice. Hoarseness or vocal weakness also can be associated with glottic stenosis and vocal cord paresis or paralysis. Always ask about a history of recurrent croup. A child with an otherwise adequate but marginal airway can become symptomatic with the development of mucosal edema associated with a routine viral upper respiratory infection (URI). Children with these conditions may have subglottic narrowing and an evaluation of the airway is appropriate. Always assess the history of GER disease (GERD). If present, always evaluate GERD prior to surgical intervention. A child who eventually has a diagnosis of subglottic stenosis (SGS) often has a history of either laryngotracheal trauma or intubation and ventilation. Frequently, these patients were born prematurely, have bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and may require oxygen administration. The degree of pulmonary disease and the amount of oxygen the child requires may affect the ability to perform decannulation. Prior to surgical intervention, the child should not require a substantial oxygen supplementation.

Physical examination

The physical examination varies depending on the degree of subglottic stenosis (SGS) present. Auscultate the child's lung fields and neck to assess any symptoms of airway obstruction and to evaluate pulmonary function. Completely evaluate the head and neck, and identify associated facial abnormalities such as cleft palate, choanal atresia, retrognathia, and facial deformities. Evaluate the child's initial overall appearance, and ask the following questions: Is the child comfortable? Does the child have difficulty breathing?

9 of 16

2/6/2012 12:14 AM

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/864208-overview

Does the child have difficulty breathing when emotionally upset? Does the child have any suprasternal, substernal, or intercostal retractions? Does the child have any nasal flaring? Is the voice normal? Is it weak? Is the voice breathy? Does the child have stridor? If so, what is the nature of the stridor (ie, inspiratory, expiratory, or biphasic)? What is the child's neurologic status? Does the child have a tracheotomy? Can the patient occlude the tracheotomy and still breathe without laboring?

Indications

Staging

Surgical reconstruction is performed on the basis of the symptoms, regardless of SGS grade. Children with grade I and mild grade II subglottic stenosis (SGS) often do not require surgical intervention. Myers and Cotton devised a classification scheme for grading circumferential subglottic stenosis from I-IV, which is established endoscopically and by using noncuffed pediatric endotracheal tubes of various sizes and sizing the airway. The scale describes stenosis as a percent of area that is obstructed. The system contains 4 grades, as follows: Grade I - Obstruction of 0-50% of the lumen obstruction Grade II - Obstruction of 51-70% of the lumen Grade III - Obstruction of 71-99% of the lumen Grade IV - Obstruction of 100% of the lumen (ie, no detectable lumen) The percentage of stenosis is evaluated by using endotracheal tubes of different sizes. The largest endotracheal tube that can be placed with an air leak less than 20 cm of water pressure is recorded and evaluated against a scale that has previously been constructed by Myers and Cotton, as depicted below.

Granulation tissue (superior center portion of the picture) that occurred at the graft site of a laryngotracheal reconstruction performed with an anterior graft.

This grading system applies mainly to circumferential stenosis and does not apply to other types of subglottic stenosis (SGS) or combined stenoses, although it can be used to obtain a rough estimate. Typically, children with grade I, as shown in the image below, or mild grade II stenosis do not require surgical intervention. Children with these conditions may have intermittent airway symptoms, especially when infection or inflammation causes mucosal edema.

10 of 16

2/6/2012 12:14 AM

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/864208-overview

Subglottic view of very mild congenital subglottic stenosis. Laterally, the area looks only slightly narrow. When endotracheal tubes were used to determine its size, it was found to be 30% narrowed.

Indications

Surgical intervention may be avoided if periods of airway obstruction are rare and can be treated on an inpatient or outpatient basis with anti-inflammatory and vasoconstrictive agents, such as oral, intravenous, or inhaled steroids and inhaled epinephrine (racemic treatment). If children with these conditions continue to have intermittent or persistent stridor and airway obstructive symptoms when they are well, or if they frequently become ill, surgical intervention may be necessary. Development of upper respiratory symptoms during routine infections can indicate whether a child with subglottic stenosis (SGS) requires surgical reconstruction. Viral infections of the upper respiratory tract can create swelling in any area of the respiratory epithelium from the tip of the nose to the lungs. If a child with subglottic stenosis (SGS) has a cold and/or bronchitis but no significant symptoms of stridor or upper airway obstruction, the airway may be large enough to tolerate stress, and reconstruction may not be needed. A history of recurrent croup suggests subglottic stenosis (SGS). Occasionally, older children have exercised-induced airway obstruction. At evaluation, these children may have grade I or grade II subglottic stenosis (SGS). Expansion of the airway with cartilage augmentation may allow them to lead a healthy and active lifestyle. Children with grade III or grade IV subglottic stenosis (SGS) need one or more of the forms of surgical treatment discussed in Surgical therapy. Although croup, bacterial infection, GERD, and bronchopulmonary dysplasia may occur or be involved in the development of subglottic stenosis (SGS), a history of prolonged endotracheal tube intubation is the most common factor seen in patients with subglottic stenosis (SGS) that requires surgical correction.

Relevant Anatomy

The subglottis is defined as the area of the larynx housed by the cricoid cartilage that extends from 5 mm beneath the true vocal cords to the inferior aspect of the cricoid ring, depicted in the image below. Because of the proximity and close relationship of the subglottis to the glottic larynx, glottic stenosis often can be present with subglottic stenosis (SGS). When SGS is corrected surgically, good voice quality can be preserved by not violating the true vocal cords if they are uninvolved in the disease process.

Intraoperative endoscopic view of a normal subglottis

When creating the entry incision into the airway in an isolated subglottic stenosis (SGS), divide the cricoid cartilage, upper 2 tracheal rings, and the inferior third to half of the laryngeal cartilage in the midline; avoid dividing the anterior commissure. However, if the disease dictates or if exposure for repair cannot be obtained without dividing the anterior commissure, carefully perform the procedure. Endoscopic guidance can help in preventing injury to the glottic larynx. If a laryngofissure is required for glottic stenosis or to gain access to the posterior aspect of the stenosis for suturing of the posterior graft, care must be taken to identify the anterior commissure and correctly put it back into place.

11 of 16

2/6/2012 12:14 AM

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/864208-overview

Once the laryngofissure is created in the midline, immediately suture the anterior aspect of the true vocal chords near the anterior commissure to the laryngeal cartilage with a 6-0 monofilament suture such as polydioxanone (PDS) or Monocryl. This procedure helps prevent anterior commissure from becoming blunted and helps mark approximately where it should be once the laryngofissure is closed. When dividing the posterior cricoid lumen, note that the esophagus is immediately adjacent and posterior to it. Take care to avoid injuring the esophagus when completely dividing the posterior cricoid lamina during cartilage augmentation. The recurrent laryngeal nerves enter the larynx in the posterior lateral portion of the cricoid ring. When surgery is performed in the midline, the recurrent laryngeal nerves should be far enough away from an anterior division to prevent injury. Any surgical procedure in which the lateral cricoid is divided could jeopardize the laryngeal nerve and result in paresis or paralysis of the true vocal cords. In the cricotracheal resection procedure, no attempt is made to identify the recurrent laryngeal nerves because of dense scarring. This lack of identification has resulted in some reported cases of paresis of the true vocal cord.

Contraindications

No specific absolute contraindications to the laryngotracheal reconstruction procedure exist. However, if general anesthesia is absolutely contraindicated, surgical correction of subglottic stenosis (SGS) cannot be performed. A relative contraindication to reconstruction of a narrow subglottis is present in children who have a tracheotomy and subglottic stenosis (SGS) but need a tracheotomy for other purposes (eg, access for suctioning secretions caused by chronic aspiration) or in those who have airway collapse or obstruction in the nasal cavity, nasopharynx, oral cavity, oropharynx, supraglottic larynx, or trachea that cannot be repaired. However, if severe or complete laryngeal obstruction exists and if the child might be able to vocalize if the airway were surgically corrected, reconstruction may be beneficial, despite the need to maintain the tracheotomy tube. Severe GER is another relative contraindication. Once GER is treated successfully (medically or surgically) or resolves on its own, reconstruction can be considered. An additional relative contraindication to airway reconstruction is pulmonary or neurological function that is inadequate to withstand tracheotomy decannulation. Regardless of the cause of subglottic stenosis (SGS), it is usually best to delay reconstructive efforts in children who have reactive or granular airways, shown below, until the reactive nature of the patient's condition subsides.

Granular subglottic stenosis in a 3-month-old infant that was born premature, weighing 800 g. The area is still granular following cricoid split. This patient required tracheotomy and eventual reconstruction at age 3 years. True vocal cords are shown in the foreground (slightly blurry).

Contributor Information and Disclosures

Author John E McClay, MD Associate Professor of Pediatric Otolaryngology, Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Children's Hospital of Dallas, University of Texas Southwestern Medical School John E McClay, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Otolaryngic Allergy, American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, American College of Surgeons, and American Medical Association Disclosure: Nothing to disclose. Specialty Editor Board Russell A Faust, MD, PhD Consulting Staff, Department of Otolaryngology, Columbus Children's Hospital

12 of 16

2/6/2012 12:14 AM

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/864208-overview

Russell A Faust, MD, PhD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, American College of Legal Medicine, American Laryngological Rhinological and Otological Society, American Rhinologic Society, American Society for Head and Neck Surgery, and American Society of Law, Medicine & Ethics Disclosure: Nothing to disclose. Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference Disclosure: Medscape Salary Employment Gregory C Allen, MD Assistant Professor, Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, University of Colorado School of Medicine Gregory C Allen, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Cleft Palate/Craniofacial Association, American College of Surgeons, American Laryngological Rhinological and Otological Society, American Medical Association, Christian Medical & Dental Society, and Colorado Medical Society Disclosure: Nothing to disclose. Christopher L Slack, MD Private Practice in Otolaryngology and Facial Plastic Surgery, Associated Coastal ENT; Medical Director, Treasure Coast Sleep Disorders Christopher L Slack, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, and American Medical Association Disclosure: Nothing to disclose. Chief Editor Arlen D Meyers, MD, MBA Professor, Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, University of Colorado School of Medicine Arlen D Meyers, MD, MBA is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, and American Head and Neck Society Disclosure: Covidien Corp Consulting fee Consulting; US Tobacco Corporation Unrestricted gift Unknown; Axis Three Corporation Ownership interest Consulting; Omni Biosciences Ownership interest Consulting; Sentegra Ownership interest Board membership; Syndicom Ownership interest Consulting; Oxlo Consulting; Medvoy Ownership interest Management position; Cerescan Imaging Honoraria Consulting; GYRUS ACMI Honoraria Consulting

References

1. Fearon B, Cotton R. Surgical correction of subglottic stenosis of the larynx in infants and children. Progress report. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. Jul-Aug 1974;83(4):428-31. [Medline]. 2. Seid AB, Pransky SM, Kearns DB. One-stage laryngotracheoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Apr 1991;117(4):408-10. [Medline]. 3. Cotton RT, O'Connor DM. Evaluation of the airway for laryngotracheal reconstruction. Int Anesthesiol Clin. Fall 1992;30(4):93-8. [Medline]. 4. Zalzal GH. Treatment of laryngotracheal stenosis with anterior and posterior cartilage grafts. A report of 41 children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Jan 1993;119(1):82-6. [Medline]. 5. Choi SS, Zalzal GH. Changing trends in neonatal subglottic stenosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Jan

13 of 16

2/6/2012 12:14 AM

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/864208-overview

2000;122(1):61-3. [Medline]. 6. Myer CM 3rd, Cotton RT. Historical development of surgery for pediatric laryngeal stenosis. Ear Nose Throat J. Aug 1995;74(8):560-2, 564. [Medline]. 7. Quesnel AM, Lee GS, Nuss RC, Volk MS, Jones DT, Rahbar R. Minimally invasive endoscopic management of subglottic stenosis in children: Success and failure. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. Mar 4 2011;[Medline]. 8. Hueman EM, Simpson CB. Airway complications from topical mitomycin C. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Dec 2005;133(6):831-5. [Medline]. 9. Schmidt RJ, Shah G, Sobin L, Reilly JS. Laryngotracheal reconstruction in infants and children: Are single-stage anterior and posterior grafts a reliable intervention at all pediatric hospitals?. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. Dec 2011;75(12):1585-8. [Medline]. 10. Seid AB, Godin MS, Pransky SM, et al. The prognostic value of endotracheal tube-air leak following tracheal surgery in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Aug 1991;117(8):880-2. [Medline]. 11. Rothschild MA, Cotcamp D, Cotton RT. Postoperative medical management in single-stage laryngotracheoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Oct 1995;121(10):1175-9. [Medline]. 12. Zalzal GH, Choi SS, Patel KM. Ideal timing of pediatric laryngotracheal reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Feb 1997;123(2):206-8. [Medline]. 13. Zalzal GH, Cotton RT. A new way of carving cartilage grafts to avoid prolapse into the tracheal lumen when used in subglottic reconstruction. Laryngoscope. Sep 1986;96(9 Pt 1):1039. [Medline]. 14. Choi SS, Zalzal GH. Pitfalls in laryngotracheal reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Jun 1999;125(6):650-3. [Medline]. 15. Baker S, Kelchner L, Weinrich B, et al. Pediatric laryngotracheal stenosis and airway reconstruction: a review of voice outcomes, assessment, and treatment issues. J Voice. Dec 2006;20(4):631-41. [Medline]. 16. Cotton RT. Management of laryngotracheal stenosis and tracheal lesions including single stage laryngotracheoplasty. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. Jun 1995;32 Suppl:S89-91. [Medline]. 17. Cotton RT. Management of subglottic stenosis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. Feb 2000;33(1):111-30. [Medline]. 18. Cotton RT, Evans JN. Laryngotracheal reconstruction in children. Five-year follow-up. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. Sep-Oct 1981;90(5 Pt 1):516-20. [Medline]. 19. Cotton RT, Gray SD, Miller RP. Update of the Cincinnati experience in pediatric laryngotracheal reconstruction. Laryngoscope. Nov 1989;99(11):1111-6. [Medline]. 20. Cotton RT, Mortelliti AJ, Myer CM 3rd. Four-quadrant cricoid cartilage division in laryngotracheal reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Oct 1992;118(10):1023-7. [Medline]. 21. Cotton RT, Myer CM 3rd, Bratcher GO, et al. Anterior cricoid split, 1977-1987. Evolution of a technique. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Nov 1988;114(11):1300-2. [Medline]. 22. Cotton RT, Myer CM 3rd, O'Connor DM, et al. Pediatric laryngotracheal reconstruction with cartilage grafts and endotracheal tube stenting: the single-stage approach. Laryngoscope. Aug 1995;105(8 Pt 1):818-21. [Medline]. 23. Cotton RT, O'Connor DM. Paediatric laryngotracheal reconstruction: 20 years' experience. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg. 1995;49(4):367-72. [Medline]. 24. Eliashar R, Gross M, Maly B, et al. Mitomycin does not prevent laryngotracheal repeat stenosis after endoscopic dilation surgery: an animal study. Laryngoscope. Apr 2004;114(4):743-6. [Medline]. 25. Hartnick CJ, Hartley BE, Lacy PD, et al. Topical mitomycin application after laryngotracheal reconstruction: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Oct 2001;127(10):1260-4. [Medline].

14 of 16

2/6/2012 12:14 AM

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/864208-overview

26. Jaquet Y, Lang F, Pilloud R, et al. Partial cricotracheal resection for pediatric subglottic stenosis: long-term outcome in 57 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. Sep 2005;130(3):726-32. [Medline]. 27. Jaquet Y, Lang F, Pilloud R, et al. Partial cricotracheal resection for pediatric subglottic stenosis: long-term outcome in 57 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. Sep 2005;130(3):726-32. [Medline]. 28. Lee KH, Rutter MJ. Role of balloon dilation in the management of adult idiopathic subglottic stenosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. Feb 2008;117(2):81-4. [Medline]. 29. Matt BH, Myer CM 3d, Harrison CJ, et al. Tracheal granulation tissue. A study of bacteriology. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. May 1991;117(5):538-41. [Medline]. 30. Myer CM 3rd, O'Connor DM, Cotton RT. Proposed grading system for subglottic stenosis based on endotracheal tube sizes. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. Apr 1994;103(4 Pt 1):319-23. [Medline]. 31. Ochi JW, Seid AB, Pransky SM. An approach to the failed cricoid split operation. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. Dec 1987;14(2-3):229-34. [Medline]. 32. Perepelitsyn I, Shapshay SM. Endoscopic treatment of laryngeal and tracheal stenosis-has mitomycin C improved the outcome?. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Jul 2004;131(1):16-20. [Medline]. 33. Rahbar R, Shapshay SM, Healy GB. Mitomycin: effects on laryngeal and tracheal stenosis, benefits, and complications. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. Jan 2001;110(1):1-6. [Medline]. 34. Schmidt D, Jorres RA, Magnussen H. Citric acid-induced cough thresholds in normal subjects, patients with bronchial asthma, and smokers. Eur J Med Res. Sep 29 1997;2(9):384-8. [Medline]. 35. Seid AB, Canty TG. The anterior cricoid split procedure for the management of subglottic stenosis in infants and children. J Pediatr Surg. Aug 1985;20(4):388-90. [Medline]. 36. Silver FM, Myer CM 3d, Cotton RT. Anterior cricoid split. Update 1991. Am J Otolaryngol. Nov-Dec 1991;12(6):343-6. [Medline]. 37. Smith ME, Marsh JH, Cotton RT, et al. Voice problems after pediatric laryngotracheal reconstruction: videolaryngostroboscopic, acoustic, and perceptual assessment. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. Jan 1993;25(1-3):173-81. [Medline]. 38. Stern Y, Gerber ME, Walner DL, et al. Partial cricotracheal resection with primary anastomosis in the pediatric age group. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. Nov 1997;106(11):891-6. [Medline]. 39. Stern Y, Willging JP, Cotton RT. Use of Montgomery T-tube in laryngotracheal reconstruction in children: is it safe?. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. Dec 1998;107(12):1006-9. [Medline]. 40. Walner DL, Heffelfinger SC, Stern Y, et al. Potential role of growth factors and extracellular matrix in wound healing after laryngotracheal reconstruction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Mar 2000;122(3):363-6. [Medline]. 41. Walner DL, Ouanounou S, Donnelly LF, et al. Utility of radiographs in the evaluation of pediatric upper airway obstruction. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. Apr 1999;108(4):378-83. [Medline]. 42. Walner DL, Stern Y, Cotton RT. Margins of partial cricotracheal resection in children. Laryngoscope. Oct 1999;109(10):1607-10. [Medline]. 43. Walner DL, Stern Y, Gerber ME, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux in patients with subglottic stenosis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. May 1998;124(5):551-5. [Medline]. 44. Zalzal GH. Rib cartilage grafts for the treatment of posterior glottic and subglottic stenosis in children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. Sep-Oct 1988;97(5 Pt 1):506-11. [Medline]. 45. Zalzal GH. Stenting for pediatric laryngotracheal stenosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. Aug 1992;101(8):651-5. [Medline]. 46. Zalzal GH, Loomis SR, Derkay CS, et al. Vocal quality of decannulated children following laryngeal reconstruction. Laryngoscope. Apr 1991;101(4 Pt 1):425-9. [Medline].

15 of 16

2/6/2012 12:14 AM

Subglottic Stenosis in Children

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/864208-overview

47. Zalzal GH, Loomis SR, Fischer M. Laryngeal reconstruction in children. Assessment of vocal quality. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. May 1993;119(5):504-7. [Medline]. 48. Zestos MM, Hoppen CN, Belenky WM, et al. Subglottic stenosis after surgery for congenital heart disease: a spectrum of severity. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. Jun 2005;19(3):367-9. [Medline]. Medscape Reference 2011 WebMD, LLC

16 of 16

2/6/2012 12:14 AM

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Secrets of Korean MedicineDocumento70 pagineSecrets of Korean Medicineemedronho4550100% (3)

- Standard Operating Procedures HospitalDocumento5 pagineStandard Operating Procedures HospitalCindy Gabayeron100% (1)

- PhilHealth Circular No. 0035, s.2013 Annex 2 List of Procedure Case RatesDocumento98 paginePhilHealth Circular No. 0035, s.2013 Annex 2 List of Procedure Case RatesChrysanthus Herrera50% (2)

- Intranatal Assessment FormatDocumento10 pagineIntranatal Assessment FormatAnnapurna Dangeti100% (1)

- Philips Achieva 3.0T TXDocumento14 paginePhilips Achieva 3.0T TXLate ArtistNessuna valutazione finora

- General Paper September 2020Documento26 pagineGeneral Paper September 2020Kumah Wisdom100% (1)

- Tbone SccaDocumento4 pagineTbone SccaArik DelacruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Authorization LetterDocumento1 paginaAuthorization LetterArik DelacruzNessuna valutazione finora

- USER Manual V1.0 enDocumento17 pagineUSER Manual V1.0 enAhmad_deedatt03Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mjms 17 2 051Documento5 pagineMjms 17 2 051Arik DelacruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Icd10 PDFDocumento765 pagineIcd10 PDFArik DelacruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Nose AnatomyDocumento6 pagineNose AnatomyArik DelacruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Pa Rot Id TumorsDocumento10 paginePa Rot Id TumorsArik DelacruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Facial Nerve7Documento12 pagineFacial Nerve7Arik DelacruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Auto Pricelist 2010 07 21Documento14 pagineAuto Pricelist 2010 07 21Arik DelacruzNessuna valutazione finora

- SourcesDocumento2 pagineSourcesArik DelacruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Auto Pricelist 2010 07 21Documento14 pagineAuto Pricelist 2010 07 21Arik DelacruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Auto Pricelist 2010 07 21Documento14 pagineAuto Pricelist 2010 07 21Arik DelacruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Prevalence of Helicobacter Pylori Infection AmongDocumento77 paginePrevalence of Helicobacter Pylori Infection AmongAbigailNessuna valutazione finora

- Prosta LacDocumento16 pagineProsta LacantoniofacmedNessuna valutazione finora

- Jessica Horsley ResumeDocumento2 pagineJessica Horsley Resumeapi-238896609Nessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Case Studies 2013 Bunaciu 179 98Documento21 pagineClinical Case Studies 2013 Bunaciu 179 98adri90Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lab 2 - Birth Spacing Policy in OmanDocumento39 pagineLab 2 - Birth Spacing Policy in OmanMeme 1234Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ca BladderDocumento11 pagineCa Bladdersalsabil aurellNessuna valutazione finora

- Oral SURGERY REVALIDA1Documento27 pagineOral SURGERY REVALIDA1Bea Y. Bas-ongNessuna valutazione finora

- Mariana Katkout, Health Psychology 7501PSYSCI (AP1) A Defense of The Biopsychosocial Model vs. The Biomedical ModelDocumento13 pagineMariana Katkout, Health Psychology 7501PSYSCI (AP1) A Defense of The Biopsychosocial Model vs. The Biomedical ModelMariana KatkoutNessuna valutazione finora

- A Comparative Analysis of Academic and NonAcademic Hospitals On Outcome Measures and Patient SatisfactionDocumento9 pagineA Comparative Analysis of Academic and NonAcademic Hospitals On Outcome Measures and Patient SatisfactionJeff LNessuna valutazione finora

- FamilyDocumento19 pagineFamilytugba1234Nessuna valutazione finora

- Pfizer Drug R&D Pipeline As of July 31, 2007Documento19 paginePfizer Drug R&D Pipeline As of July 31, 2007anon-843904100% (1)

- Mindmap METENDocumento1 paginaMindmap METENIpulCoolNessuna valutazione finora

- Protocolo Cochrane REHABILITACIÓN COGNITIVA en Demencia (2019)Documento17 pagineProtocolo Cochrane REHABILITACIÓN COGNITIVA en Demencia (2019)Sara Daoudi FuentesNessuna valutazione finora

- C Reactive ProteinDocumento24 pagineC Reactive ProteinMohammed FareedNessuna valutazione finora

- Association of Dental Anomalies With Different Types of Malocclusions in PretreatmentDocumento5 pagineAssociation of Dental Anomalies With Different Types of Malocclusions in PretreatmentLucy Allende LoayzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal Remifentanyl For Pain LaborDocumento11 pagineJurnal Remifentanyl For Pain LaborAshadi CahyadiNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan On Hypertension 1Documento11 pagineLesson Plan On Hypertension 1Samiran Kumar DasNessuna valutazione finora

- EfficacyDocumento7 pagineEfficacyAniend Uchuz ChizNessuna valutazione finora

- Maternal Serum Alpha-Fetoprotein (MSAFP)Documento2 pagineMaternal Serum Alpha-Fetoprotein (MSAFP)Shaells JoshiNessuna valutazione finora

- Minnesota Fall School Planning Guide - Minnesota Department of HealthDocumento16 pagineMinnesota Fall School Planning Guide - Minnesota Department of HealthPatch Minnesota100% (1)

- Crash Cart ICU EMRDocumento5 pagineCrash Cart ICU EMRRetteri KUMARANNessuna valutazione finora

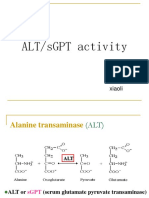

- SgotsgptDocumento23 pagineSgotsgptUmi MazidahNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparison of Intravitreal Bevacizumab (Avastin) With Triamcinolone For Treatment of Diffused Diabetic Macular Edema: A Prospective Randomized StudyDocumento9 pagineComparison of Intravitreal Bevacizumab (Avastin) With Triamcinolone For Treatment of Diffused Diabetic Macular Edema: A Prospective Randomized StudyBaru Chandrasekhar RaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal Pediatric IndiaDocumento5 pagineJournal Pediatric IndiaHhhNessuna valutazione finora

- Egypt Biosimilar Guidline Biologicals RegistrationDocumento54 pagineEgypt Biosimilar Guidline Biologicals Registrationshivani hiremathNessuna valutazione finora