Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Lewis, A. Et Al. Research Resin Mummy. 2010

Caricato da

Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Lewis, A. Et Al. Research Resin Mummy. 2010

Caricato da

Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Inside The Conservator's Art

A behind-the-scenes look at conserving Egyptian artifacts at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology http://conservationblog.hearstmuseum.dreamhosters.com/?p=277 { 2010 01 04 }

Researching resin

Unwrapped crocodile mummy PAHMA 5-513 is covered with a shiny black coating which we are studying and conserving. Embalmers applied the black material in liquid form directly to much of the crocodiles (and baby crocodiles) skin, evidenced by the drips, smears and bubbles. The black coating presumably contains compounds that have antibacterial properties, and contributed to the long-term preservation of the tissue. It has a resinous appearance, in that it looks like it was a viscous liquid that has formed a shiny film or coating. Although the term resin is frequently used to describe such coatings on Egyptian mummies, in these contexts it refers only to the materials appearance rather than to its chemical composition. Whatever the coating is made of, it has deteriorated and is no longer stable. Networks of cracks have formed in many locations, causing pieces of various sizes to detach.

Shattered resin coating before treatment, PAHMA 5-513. The black coating on PAHMA 5-513 raises questions about ancient Egyptian mummification practices and present day stabilization measures for the crocodile mummy. What kinds of materials make up this substance? What does the coatings appearance reveal about the mummification techniques used to prepare the crocodile body? Is the black coating similar to embalming materials used to mummify human beings? What about other animal mummies, and other crocodile mummies? How costly vs. low-end were these materials in ancient Egypt, and what does that tell us about how the mummy was used and valued? From a practical standpoint, again, what is this material? Why is it deteriorating in this manner? What is its compatibility with potential conservation materials that we can use to treat the shattered and detaching coating? What sort of environment will best preserve it? In order to answer one of the big questions, the composition of the black coating, we have submitted samples of it to Dr. Richard Evershed at the University of Bristol, United Kingdom. He and his team will use chromatographic and spectroscopic analytical techniques to characterize the compounds present in the

black substance. In some of his previous research into animal mummy balms, Dr. Evershed and has found mixtures of biomarker components characteristic of fats, oils, beeswax, sugar gum, petroleum bitumen, and several plant resins. These mixtures are similar to the highly complex mixtures used to embalm human mummies from the same period.

Mummification balm samples from three PAHMA mummies ready to be sent for analysis. However, due to time constraints, I must treat the crocodile mummy before we learn the results of the scientific analysis. Therefore I am using more low-tech methods, including visual observation under regular and ultraviolet illumination, microchemical spot tests, and solubility tests to characterize the black coating. In order to see if I could detect plant resins, which have been found in human and animal mummies from this period, I performed a microchemical spot test called the Raspail test on a sample of the coating. The Raspail test (detailed in Odegaard, Carroll and Zimmts excellent spot test book) entails droppering the sample with a saturated solution of sugar in deionized water, mopping up the excess sugar solution, then placing a drop of concentrated sulfuric acid on the sample. When some types of natural resins are present, the solution turns a bright raspberry red over the course of about 20 minutes. I always run a blank (a sample of the same material that is not treated with the sugar solution) because sulfuric acid tends to turn a lot things red/brown, and it helps to be able to see the effect of acid alone. Here are some examples of positive Raspail tests, on sap from a tree and on a piece of fossilized resin:

Examples of positive Raspail test results. Top: sap. Bottom: fossilized resin (amber) and blank. The crocodile mummy coating did not produce a positive result. Both the sample and the control turned the same brownish color, and no raspberry red was observed.

Raspail test results for the black coating from 5-513. This test result doesnt rule out the possibility that plant resins are part of the embalming fluid mixture. They may have been chemically altered during thousands of years of burial, be present in low levels, or simply be of a type that is not responsive to this test.

In order to select the best materials to consolidate (introduce an adhesive to restore integrity to the coating and halt the loss of small pieces) the shattered coating, I also performed solubility tests to see how different solvents interact with the black substance. After tests with a cotton swab and direct immersion of tiny samples, it became clear that the black coating is soluble in more polar solvents including acetone and ethanol, and insoluble in water and petroleum distillates like Stoddard solvent and benzine.

Solubility test results for black coating from 5-513. Because acetone and ethanol partially dissolve the black coating, I will not use an adhesive that is carried in these solvents. Water presents another problem because of the composite nature of the mummy. While water appears to be safe to use on the coating, it affects the moisture-sensitive skin below. So far the petroleum-based solvents appear to be safest way to go when both the coating and the crocodile skin are taken into account, but this limits my choice of consolidants. I will conduct more tests with the potential consolidants themselves before selecting appropriate materials.

Posted by Allison on Monday, January 4, 2010, at 4:48 pm. Filed under Conservation treatments, Mummies and mummification. Tagged Scientific analysis, Spot tests. Follow any responses to this post with its comments RSS feed. You can post a comment or trackback from your blog.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Semen and seminal stain identificationDocumento25 pagineSemen and seminal stain identificationAmber Ebaya100% (1)

- Primary Healthcare Centre Literature StudyDocumento32 paginePrimary Healthcare Centre Literature StudyRohini Pradhan67% (6)

- Case Study - BronchopneumoniaDocumento45 pagineCase Study - Bronchopneumoniazeverino castillo91% (33)

- VVAA. Rock Art. Gci. 2006Documento32 pagineVVAA. Rock Art. Gci. 2006Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-Conservación100% (1)

- Ukite 2011Documento123 pagineUkite 2011pikacu19650% (2)

- Nanomaterials Used in Conservation and RDocumento24 pagineNanomaterials Used in Conservation and RSidhartha NatarajaNessuna valutazione finora

- Comprehensive Guide to Furniture ConservationDocumento2 pagineComprehensive Guide to Furniture ConservationSalander21Nessuna valutazione finora

- Semen AND Seminal Stain: By: Group 3Documento20 pagineSemen AND Seminal Stain: By: Group 3Amber EbayaNessuna valutazione finora

- Museum International - Preventive ConservationDocumento62 pagineMuseum International - Preventive ConservationDan Octavian PaulNessuna valutazione finora

- A Set of Conservation Guidelines For ExhibitionsDocumento17 pagineA Set of Conservation Guidelines For ExhibitionsMien MorrenNessuna valutazione finora

- Smith - Archaeological Conservation Using Polymers PDFDocumento144 pagineSmith - Archaeological Conservation Using Polymers PDFyadirarodriguez23100% (1)

- Catherine Sease-The Conservation of Archeological MaterialsDocumento15 pagineCatherine Sease-The Conservation of Archeological MaterialsDaniel DoowyNessuna valutazione finora

- Corfield, N. y Williams, J. Preservation of Archaeological Remains in Situ. 2011Documento7 pagineCorfield, N. y Williams, J. Preservation of Archaeological Remains in Situ. 2011Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Sensitivity of Coloured Materials and Time To Fade 1 - 0Documento2 pagineSensitivity of Coloured Materials and Time To Fade 1 - 0Veljko DžikićNessuna valutazione finora

- Semen and Seminal StainDocumento25 pagineSemen and Seminal StainArman Domingo40% (15)

- Caring For Artifacts After Excavation PDFDocumento14 pagineCaring For Artifacts After Excavation PDFadonisghlNessuna valutazione finora

- New Methodologies For The Conservation of Cultural Heritage Micellar Solutions Microemulsions, and Hydroxide NanoparticlesDocumento10 pagineNew Methodologies For The Conservation of Cultural Heritage Micellar Solutions Microemulsions, and Hydroxide Nanoparticlesgemm88Nessuna valutazione finora

- Rigid Gels and Enzyme Cleaning of ArtworksDocumento5 pagineRigid Gels and Enzyme Cleaning of ArtworksCristi CostinNessuna valutazione finora

- Burns SeminarDocumento66 pagineBurns SeminarPratibha Thakur100% (1)

- Improving Collaboration Between Conservation and ArcheologyDocumento28 pagineImproving Collaboration Between Conservation and ArcheologyEsther GómezNessuna valutazione finora

- E Conservationmagazine26Documento130 pagineE Conservationmagazine26InisNessuna valutazione finora

- Reading Artefacts Summer Institute SyllabusDocumento22 pagineReading Artefacts Summer Institute SyllabusJean-François GauvinNessuna valutazione finora

- VVAA. Conservation Decorated Architectural Surfaces. GCI. 2010Documento29 pagineVVAA. Conservation Decorated Architectural Surfaces. GCI. 2010Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-Conservación100% (1)

- Notes On Archeological ConservationDocumento9 pagineNotes On Archeological Conservationm_bohnNessuna valutazione finora

- A Novel Approach To Cleaning II: Extending The Modular Cleaning Program To Solvent Gels and Free Solvents, Part 1Documento7 pagineA Novel Approach To Cleaning II: Extending The Modular Cleaning Program To Solvent Gels and Free Solvents, Part 1s.mashNessuna valutazione finora

- Chemicals and Methods for Conservation and Restoration: Paintings, Textiles, Fossils, Wood, Stones, Metals, and GlassDa EverandChemicals and Methods for Conservation and Restoration: Paintings, Textiles, Fossils, Wood, Stones, Metals, and GlassNessuna valutazione finora

- E Conservationmagazine24Documento190 pagineE Conservationmagazine24Inis100% (1)

- Cart Wright, C. Et Al. Wood Identification and Conservation. 2009Documento11 pagineCart Wright, C. Et Al. Wood Identification and Conservation. 2009Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Standley, N. The Great Mural. Conserving The Rock Art of Baja California. 1996Documento9 pagineStandley, N. The Great Mural. Conserving The Rock Art of Baja California. 1996Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- FLSPfister IB05000 I GBTRWSD0216 MailDocumento26 pagineFLSPfister IB05000 I GBTRWSD0216 MailLuis Angel BusturiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mat. Org. in Pictura Mur PDFDocumento140 pagineMat. Org. in Pictura Mur PDFIngrid GeorgescuNessuna valutazione finora

- Abbas, H. Deterioration Rock Inscriptions Egypt. 2011Documento15 pagineAbbas, H. Deterioration Rock Inscriptions Egypt. 2011Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- A Guide To The Preventive Conservation of Photograph Collections (Bertrand Lavédrine)Documento308 pagineA Guide To The Preventive Conservation of Photograph Collections (Bertrand Lavédrine)Dan Octavian PaulNessuna valutazione finora

- Conservation and Restoration: Chapter 1.2Documento17 pagineConservation and Restoration: Chapter 1.2Maja Con DiosNessuna valutazione finora

- Lewis, A. Et Al. CT Scanning Cocodrile Mummies. 2010Documento7 pagineLewis, A. Et Al. CT Scanning Cocodrile Mummies. 2010Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Van Giffen, A. Conservation of Islamic Jug. 2011Documento5 pagineVan Giffen, A. Conservation of Islamic Jug. 2011Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Torraca, G. The Scientist in Conservation. Getty. 1999Documento6 pagineTorraca, G. The Scientist in Conservation. Getty. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Mist Lining HandbookDocumento106 pagineMist Lining HandbookBigornooNessuna valutazione finora

- Van Giffen, A. Conservation of Venetian Globet. 2011Documento2 pagineVan Giffen, A. Conservation of Venetian Globet. 2011Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Lampropoulos V. Et Al. Ploughing Unusual Corrosion Archaeological GlassDocumento5 pagineLampropoulos V. Et Al. Ploughing Unusual Corrosion Archaeological GlassTrinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Lewis, A. Et Al. Preliminary Results Cocodrile Mummy. 2010Documento7 pagineLewis, A. Et Al. Preliminary Results Cocodrile Mummy. 2010Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Chemical Conservation of CeramicsDocumento10 pagineChemical Conservation of CeramicsKrisha DesaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Lewis, A. Et Al. Conserving A Car Tonnage Foot Case. 2010Documento8 pagineLewis, A. Et Al. Conserving A Car Tonnage Foot Case. 2010Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Van Giffen, A. Glass Corrosion. Weathering. 2011Documento3 pagineVan Giffen, A. Glass Corrosion. Weathering. 2011Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Glass and CeramicsDocumento2 pagineGlass and CeramicsstudimanNessuna valutazione finora

- Reintegración Vidrio Arqueológico. E-ConservationDocumento16 pagineReintegración Vidrio Arqueológico. E-ConservationTrinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Creating A Microclimate Box For Metal StorageDocumento3 pagineCreating A Microclimate Box For Metal StorageJC4413100% (1)

- Investigating Shellac by Juliane DerryDocumento171 pagineInvestigating Shellac by Juliane DerryTiffany YoungNessuna valutazione finora

- E-Conservation Magazine - Conservation of A Persian CarpetDocumento8 pagineE-Conservation Magazine - Conservation of A Persian CarpetPatrick CashmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Wayne, C. Et Al. Silicone Oil. A New Technique Preserving Waterlogged RopeDocumento13 pagineWayne, C. Et Al. Silicone Oil. A New Technique Preserving Waterlogged RopeTrinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- CRL. Hamilton, D. Methods of Conserving Archaeological Material From Underwater Sites. 1999Documento110 pagineCRL. Hamilton, D. Methods of Conserving Archaeological Material From Underwater Sites. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-Conservación100% (1)

- Care of Archaeological FindsDocumento17 pagineCare of Archaeological FindsJaime Mujica Salles100% (1)

- Smith - Archaeological Conservation Using PolymersDocumento144 pagineSmith - Archaeological Conservation Using PolymersWASHINGTON CAVIEDESNessuna valutazione finora

- Glossary of Conservation TermsDocumento11 pagineGlossary of Conservation TermsDan Octavian Paul100% (1)

- Rockarticles 18Documento13 pagineRockarticles 18Kate SharpeNessuna valutazione finora

- Cano, E. Electrochemical Protection System Mtal Artefacts. 2010Documento30 pagineCano, E. Electrochemical Protection System Mtal Artefacts. 2010Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Al-Saad, Z. y Bani, M. Corrosion and Preservation Islamic Silver Coins. 2007Documento8 pagineAl-Saad, Z. y Bani, M. Corrosion and Preservation Islamic Silver Coins. 2007Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-Conservación100% (1)

- CHEMICAL PROCESSING OF TEXTILES - DYEING AND PRINTINGDocumento86 pagineCHEMICAL PROCESSING OF TEXTILES - DYEING AND PRINTINGOmkar JadhavNessuna valutazione finora

- RSDTGFHGJHKJLDocumento18 pagineRSDTGFHGJHKJLManuel BochacaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mottner, P. Dosimeters Monitoring Indoor Museum Climate. 2007Documento6 pagineMottner, P. Dosimeters Monitoring Indoor Museum Climate. 2007Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Polychrome Sculpture Tool Marks Construc PDFDocumento16 paginePolychrome Sculpture Tool Marks Construc PDFAnaLizethMataDelgadoNessuna valutazione finora

- Agrawal Conservation Metals Humid SpacesDocumento138 pagineAgrawal Conservation Metals Humid SpacesDan Octavian PaulNessuna valutazione finora

- Kim Muir Paper PDFDocumento8 pagineKim Muir Paper PDFKunta KinteNessuna valutazione finora

- Glass and Ceramics Conservation PDFDocumento25 pagineGlass and Ceramics Conservation PDFÖzlem Çetin100% (1)

- Coles Experimental Archaeology PDFDocumento22 pagineColes Experimental Archaeology PDFEmilyNessuna valutazione finora

- Richmond, A. The Ethics Checklist. Ten Years On. 2005Documento9 pagineRichmond, A. The Ethics Checklist. Ten Years On. 2005Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Damage Diagnosis On Stone Monuments - Weathering Forms, Damage Categories and Damage Indices PDFDocumento49 pagineDamage Diagnosis On Stone Monuments - Weathering Forms, Damage Categories and Damage Indices PDFIdaHodzicNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 3 Semen and Seminal StainDocumento6 pagineChapter 3 Semen and Seminal StainRaymar BartolomeNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 Forensic Prelim Third DiscussionDocumento9 pagine3 Forensic Prelim Third Discussionmv9k6rq5ncNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 1Documento3 pagineChapter 1JohnRioG.Avergonzado0% (2)

- Semen & Seminal StainsDocumento15 pagineSemen & Seminal StainsDante Bacud Formoso IIINessuna valutazione finora

- Topic 3. SEMEN SEMINAL STAIN and OTHER STAINSDocumento5 pagineTopic 3. SEMEN SEMINAL STAIN and OTHER STAINSJack Miller DuldulaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Identification of Polymers: David A. KatzDocumento8 pagineIdentification of Polymers: David A. KatzMohit ChopraNessuna valutazione finora

- Chalk AvaDocumento22 pagineChalk AvaElla OcomenNessuna valutazione finora

- Nardi, R. New Approach To Conservation Education. 1999Documento8 pagineNardi, R. New Approach To Conservation Education. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Godonou, A. Documentation in Service of Conservation. 1999Documento6 pagineGodonou, A. Documentation in Service of Conservation. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Krebs, M. Strategy Preventive Conservation Training. 1999Documento5 pagineKrebs, M. Strategy Preventive Conservation Training. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Wressning F. Conservation and Tourism. 1999Documento5 pagineWressning F. Conservation and Tourism. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Milner, C. Conservation in Contemporary Context. 1999Documento7 pagineMilner, C. Conservation in Contemporary Context. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- De Guichen, G. Preventive Conservation. 1999Documento4 pagineDe Guichen, G. Preventive Conservation. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-Conservación0% (1)

- Druzik, J. Research On Museum Lighting. GCI. 2007Documento6 pagineDruzik, J. Research On Museum Lighting. GCI. 2007Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Kissel, E. The Restorer. Key Player in Preventive Conservation. 1999Documento8 pagineKissel, E. The Restorer. Key Player in Preventive Conservation. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Blanc He Gorge, E. Preventive Conservation Antonio Vivevel Museum. 1999Documento7 pagineBlanc He Gorge, E. Preventive Conservation Antonio Vivevel Museum. 1999Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Risser, E. New Technique Casting Missing Areas in Glass. 1997Documento9 pagineRisser, E. New Technique Casting Missing Areas in Glass. 1997Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- MacCannell D. Cultural Turism. Getty. 2000Documento6 pagineMacCannell D. Cultural Turism. Getty. 2000Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Van Giffen, A. Medieval Biconical Bottle. 2011Documento6 pagineVan Giffen, A. Medieval Biconical Bottle. 2011Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- VVAA. A Chemical Hygiene PlanDocumento8 pagineVVAA. A Chemical Hygiene PlanTrinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Odegaard, N. Collaboration in Preservation of Etnograhic and Archaeological Objects. GCI. 2005Documento6 pagineOdegaard, N. Collaboration in Preservation of Etnograhic and Archaeological Objects. GCI. 2005Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Eremin, K. y Walton, M. Analysis of Glass Mia GCI. 2010Documento4 pagineEremin, K. y Walton, M. Analysis of Glass Mia GCI. 2010Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Lewis, A. Et Al. Discuss Reconstruction Stone Vessel. 2011Documento9 pagineLewis, A. Et Al. Discuss Reconstruction Stone Vessel. 2011Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Levin, J. Nefertari Saving The Queen. 1992Documento8 pagineLevin, J. Nefertari Saving The Queen. 1992Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Fischer, C. y Bahamondez M. Moai. Environmental Monitoring and Conservation Mission. 2011Documento15 pagineFischer, C. y Bahamondez M. Moai. Environmental Monitoring and Conservation Mission. 2011Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Doehne, E. Travertine Stone at The Getty Center. 1996Documento4 pagineDoehne, E. Travertine Stone at The Getty Center. 1996Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNessuna valutazione finora

- Ketamine Drug Study for AnesthesiaDocumento1 paginaKetamine Drug Study for AnesthesiaPRINCESS MARIZHAR OMARNessuna valutazione finora

- A-Plus Beyond Critical Shield & A-Plus Beyond Early Critical ShieldDocumento21 pagineA-Plus Beyond Critical Shield & A-Plus Beyond Early Critical ShieldGenevieve KohNessuna valutazione finora

- Rockaway Times 11-21-19Documento44 pagineRockaway Times 11-21-19Peter MahonNessuna valutazione finora

- B Cell Cytokine SDocumento11 pagineB Cell Cytokine Smthorn1348Nessuna valutazione finora

- Development and Validation of Stability Indicating RP-HPLC Method For Simultaneous Estimation of Sofosbuvir and Ledipasvir in Tablet Dosage FormDocumento4 pagineDevelopment and Validation of Stability Indicating RP-HPLC Method For Simultaneous Estimation of Sofosbuvir and Ledipasvir in Tablet Dosage FormBaru Chandrasekhar RaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Practical Laser Diodes GuideDocumento4 paginePractical Laser Diodes GuideM Xubair Yousaf XaiNessuna valutazione finora

- 631 500seriesvalves PDFDocumento2 pagine631 500seriesvalves PDFsaiful_tavipNessuna valutazione finora

- Dasar Genetik GandumDocumento282 pagineDasar Genetik GandumAlekkyNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparison Between China and Sri-Lanka GDPDocumento6 pagineComparison Between China and Sri-Lanka GDPcracking khalifNessuna valutazione finora

- 22Documento22 pagine22vanhau24Nessuna valutazione finora

- WILLIEEMS TIBLANI - NURS10 Student Copy Module 15 Part1Documento32 pagineWILLIEEMS TIBLANI - NURS10 Student Copy Module 15 Part1Toyour EternityNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 12: CERT Basic Training Unit 7 ReviewDocumento11 pagineUnit 12: CERT Basic Training Unit 7 Reviewdonald1976Nessuna valutazione finora

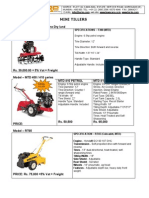

- Optimize soil preparation with a versatile mini tillerDocumento2 pagineOptimize soil preparation with a versatile mini tillerRickson Viahul Rayan C100% (1)

- Outcome of Pelvic Fractures Identi Fied in 75 Horses in A Referral Centre: A Retrospective StudyDocumento8 pagineOutcome of Pelvic Fractures Identi Fied in 75 Horses in A Referral Centre: A Retrospective StudyMaria Paz MorenoNessuna valutazione finora

- Surface BOP Kill SheetDocumento12 pagineSurface BOP Kill Sheetzouke2002Nessuna valutazione finora

- Clarifying Questions on the CPRDocumento20 pagineClarifying Questions on the CPRmingulNessuna valutazione finora

- Technical PaperDocumento10 pagineTechnical Paperalfosoa5505Nessuna valutazione finora

- Frontline ArticleDocumento7 pagineFrontline Articleapi-548946265Nessuna valutazione finora

- High Voltage - WikipediaDocumento7 pagineHigh Voltage - WikipediaMasudRanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Top Sellers Fall Protection Catalogue 2020 ENDocumento44 pagineTop Sellers Fall Protection Catalogue 2020 ENtcNessuna valutazione finora

- Uia Teaching Hospital BriefDocumento631 pagineUia Teaching Hospital Briefmelikeorgbraces100% (1)

- Marine Pollution Bulletin: Sivanandham Vignesh, Krishnan Muthukumar, Rathinam Arthur JamesDocumento11 pagineMarine Pollution Bulletin: Sivanandham Vignesh, Krishnan Muthukumar, Rathinam Arthur JamesGeorgiana-LuizaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Two-Headed Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia Mydas) Hatchling On Samandağ Beach, TurkeyDocumento6 pagineA Two-Headed Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia Mydas) Hatchling On Samandağ Beach, TurkeysushiNessuna valutazione finora

- Spez KR QUANTEC Prime enDocumento155 pagineSpez KR QUANTEC Prime enDave FansolatoNessuna valutazione finora

- Tle 7 - 8 Curriculum MapDocumento11 pagineTle 7 - 8 Curriculum MapKristianTubagaNessuna valutazione finora