Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Is Masculinity A Prerequisite To Female Managerial Advancement in

Caricato da

Scorpian MouniehDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Is Masculinity A Prerequisite To Female Managerial Advancement in

Caricato da

Scorpian MouniehCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Is masculinity a prerequisite to female managerial advancement in Pakistan?

Author: Shehla Riza Arifeen Associate Professor School of Business Administration Lahore School of Economics 104-C-2, Gulberg 3, Lahore Pakistan. Telephone: 92-42-6560938, FAX: 92-42-5712231 Email: shehla.arifeen@gmail.com shehla@lahoreschool.edu.pk

1

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1484692

Is masculinity a prerequisite to female managerial advancement in Pakistani society?

Abstract Global research on women in management has focused on the male managerial model or masculinity as important to female managerial advancement. This study is of significance because it demonstrates that it has been difficult for the managerial women of Pakistan to break away from the traditional role expectations defined by their society. Gender role identity occurs as a result of rearing patterns. It is social practice that determines gender role identity. Women usually acquire a great deal of sex role learning early in their lives. Undoing that learning process takes time, which is why, there was no dominant gender role orientation of managerial women in Pakistan. Our study demonstrates gender role orientations for women in management can be overshadowed by their unique socio-cultural environments. Unlike the global literature which does not place a positive value on undifferentiated individuals, undifferentiated gender identity is not a barrier to womens managerial advancement in Pakistan

Key words: Gender role identity, Pakistan, advancement, women managers, society.

2

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1484692

INTRODUCTION Global research has demonstrated that gender role identity or sex role orientation is associated with leader emergence (Dorbrzynski 1996; Fagenson 1990; Goktepe and Schneier 1989; Guy 1992; Kent and Moss 1994; Rosener 1995; Brewer et al.2002; Bosak & Sczesny 2008) and specifically leadership and masculinity are closely linked(Alvesson & Billing 2000; Powell,Butterfield & Parent 2002) . Eagly and Johnson( 1990) showed that women managers in male dominated industries tended to emulate more stereo typically masculine leadership style. It seems that women in managerial positions adapt themselves to conform to masculine standards thereby reinforcing the stereotype that men or masculine characteristics are more desirable in management. Twenge(1997) reported that womens self reported masculinity scores were rising over time. Chambers( 1999) established that the stereotypical view of a manager as exhibiting mostly masculine behavior still holds true. Claes(1999) discovered that from a cross cultural perspective, the right managerial skills are masculine skills. Duehr and Bono (2006) reported increase in perceived masculinity and agency of women. Women usually acquire a great deal of sex role learning or gender role identity, early in their lives leading to an attitude that creates difficulties later in working lives( Lipsey et al 1990). Gender Role identity is the perception of an individual about themselves as a specific gender. One of the measures employed for gender role identity is the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI) (Bem, 1974,1975) which classifies individuals into four classes of gender identity: masculine feminine, androgynous and undifferentiated and has been used in psychological and social psychological research( Woolf & Maisto 2008). Gender role identity has been used to explore various areas of work related behaviors. Feminine women tend to select feminine dominant careers with low status and limited opportunities( Gianakos and Subich 1988).Their behavior receives approval from others and 3

they experience less interpersonal strain( Long 1989).However, femininity at times weakens future career progress( Bhatnagar 1988).Masculine working females are associated with strong feelings of personal accomplishments and higher attainments in occupational status( Eichinger et al. 1991). An association between androgyny and more effective behavior was observed in a variety of non organizational situations( Bem 1975).It is also allied to strong decision making, self-efficacy and involvement in career exploration( Gianakos 1995).Undifferentiated individuals demonstrated low selfesteem(Chow 1987). The purpose of this study therefore, was foremost to investigate the gender role identity of managerial women in Pakistan. Gender role identity of managerial women in Pakistan had never been explored and it was essential to find out if the rules of the game were the same. The second objective was to investigate if there was an association between masculine and androgynous gender role identity and rapid managerial advancement. This research is of significance because it looks at a relatively unexplored area; Pakistani managerial women and gender role orientations. It also demonstrates that masculinity is not a prerequisite for managerial advancement in the private sector in Pakistan. Conversely, femininity, which is valued so highly in the Pakistani society, is a deterrent to managerial advancement. The study demonstrates that because gender role identity occurs as a consequence of rearing patterns and social practice, gender role orientations for women in management can be overshadowed by their unique socio-cultural environments. SOCIETAL CONTEXT Pakistan, a predominantly Muslim country, situated in Asia, ranks globally amongst the lowest statistics in gender empowerment and gender development measures(Human Development Report 2005).Even though roughly 48% of its 160 million population is female,

it is a neglected population set with low literacy, high mortality rates in childbearing years and general ill health. ( Hussein, Mumtaz and Saigol 1997). Each of the four provinces, NWFP, Baluchistan, Sindh and Punjab, has its own set of norms and practices. Women in rural Punjab and Sindh participate in the agriculture sector mainly to support family food supply. Consequently they are more visible as compared to NWFP and Baluchistan where Pardah ( the act of veiling ) is strictly observed.( Shah and Butalo1981 ; Mumtaz and Shaheed 1987 ) Gender role expectations among both men and women are traditional. In cross cultural/cross national studies of gender role ideology, (William and Best 1990) males were found biased towards a more traditional gender role ideology (Nigeria, Pakistan, India, Japan, and Malaysia) and women exhibited more liberal attitudes towards womens roles except for Pakistan and Malaysia. Relative to other countries studied stereotype scores were unusually high in Pakistan for both men and women. A womans primary role is parental and conjugal. Divorce is generally frowned upon and strong negative stereotypes exist regarding working women. Chastity has a high value and confining women to Chador (veil) and Chardiwari (boundary wall) is a way of ensuring it. Segregation is a norm. There are separate lines for men and women at all public places. Separate sections exists in public buses for men and women. Separate all girls school and colleges are the norm. The government of Pakistan has taken initiatives to encourage female participation in the work force by setting up all women police stations, banks and post offices. In a predominantly male air force and police force, a handful of female pilots or traffic police wardens serve as tokens rather than change agents. A report on the status of women employment in public sector organizations( Government of Pakistan 2003) states There is a virtual absence of women in posts that carry power, status and prestige and in those which are considered to be decision making posts. Lack of higher education coupled with social stigma,

results with few women entering the office work force in the form of either clerical category or the Legislators, Senior official, Manager Technicians , Associates & Professionals category. LITERATURE REVIEW and HYPOTHESES Gender role is a set of expected behaviors (masculine /feminine) that society associates with being physically male or female. It is a form of culture trap..a form of social determinism whereby individuals are trapped into stereotypes, which people then choose to maintain as customs( Claes1999). The social construction of gender can be influenced by underlying ideologies affecting world view( Unger,Draper and Pendergrass 1986, Unger, Gareis and Locher 2007) and religious ideology, which can either interact or override gender in attitudes about social and political issues.( Unger 1992, 2005) In most of the world the male role is described as agentic, getting things done and the female role as communal-keeping the group together and contented, with cultures conveying shared expectations for appropriate behavior. (Eagly 1987, Eagly,Wood and Diekman 2000) With agentic qualities behavior is primarily assertive, goal directed, controlling, aggressive, ambitious, dominant, independent, self-reliant, self-sufficient, direct and decisive. Studies which have shown that males have more agentic qualities and female have more communal qualities(Bem 1974; Rosner1990).The communal dimensions represent a concern with the welfare of other people. They include nurturance, affection, ability to devote self to the other, eagerness to soothe hurt feelings, helpfulness, sympathy, awareness of the feelings of other, and emotional expressiveness. Traditional gender roles emphasize separate focus for men and women, with women in the house and men outside (Duncun, Peterson and Winter 1997). Modern or liberal view is that both genders may carry out tasks or behaviors traditionally assigned to the other sex (Blee and Tickamyer 1997). Consequently men aspire to enter male

dominated occupations, which demand agentic qualities and females aspire to entire occupations expecting communal qualities.( Wigfield et al 2000). Gender Role identity is the perception of an individual about themselves as a specific gender. In most cases gender role identity matches with biological sex. Gender role identity is a subset of gender roles that an individual actually displays. Gender role identity occurs as a result of rearing patterns and not by hormones. It is social practice that determines gender role identity. Culture plays a major part in role expectations as they shape cognitive schemas or sets of shared meanings within a group of people ( Erez and Earley 1993). Differences in the value structure of men and women generally and within cultural groups is documented(DeVaus & McCallister 1991; Stimpson, Jenson and Neff 1992; Vacha-Haasa et al 1994). Bem (1974,1975) has classified gender role identity as Masculine, Feminine, Androgynous and Undifferentiated. Bem argued that (1) masculinity and femininity are complementary, not opposite positive domains of traits and behaviors, (2) an individual of either sex may be both masculine and feminine, or instrumental and expressive, depending on the given situation, and (3) it is each individuals sex-role identity, not sex, that magnifies the degree to which certain traits and behaviors are manifested. Individuals are classified as (1) Masculine, if they are male sex with masculine gender role identity (Sex- typed)or female sex with masculine gender role identity. (Cross sex- typed) and posses very few, if any feminine traits.(2 ) Feminine, if they are female sex with feminine gender role identity (Sextyped ) or male sex with feminine gender role identity (Cross sex- typed) and possess very few, if any masculine traits. (3 )Androgynous, if they are female sex with high feminine and high masculine gender role identity or male sex with high masculine and high feminine gender role identity. They must display both types of traits and approximately equal number of both male and female traits. (4) Undifferentiated, if they are female sex with few, if any,

feminine and few, if any, masculine gender role identity or male sex with few, if any, masculine and few, if any, feminine gender role identity. (Not sex typed). Bem (1981) focused more on gender schema then on gender role reported that masculine and feminine individuals were more likely to use gender as an organizing principle in information processing then were androgynous individuals. Later Bem(1993) suggested that many of the choices we make about our own behavior are to varying degree guided by cultural expectations of our gender. This cultural gender role information is used to form our self concept. Therefore, gender role expectations for both men and women will be based on how each society disseminates information and conditions its members. Goktepe and Schneier (1989), in organizational contexts found that sex had no effect on leader emergence, but gender role did. Specifically, masculine subjects were more likely to emerge as leaders than feminine, androgynous, and undifferentiated individuals. Brenner, Tomkiewicz and Schein( 1989) simulated the original Schein study on both male and female management . They found that female managers described the successful middle manager as possessing both stereotypically masculine and feminine characteristics (androgynous). A field study by Fagenson (1990) produced results similar to the Goktepe study. Men and women who were high in an organizational hierarchy were significantly higher on measures of masculinity than were lower-level workers. It appears that the possession of feminine characteristics is detrimental to leader emergence, and the possession of masculine characteristics is beneficial. Kent and Moss (1994) concluded. If women are more likely to be androgynous, they may have better chances of rising to leadership status. Studies proved androgyny and higher self expectations and better performance in competitive situations( Algana,1982)and higher levels of self esteem and job satisfaction( Chow 1987; Eichinger,Heifetz and Ingraham 1991,Krausz et al 1992; Ushasree, Seshu and Vinolya,1995). Consequently there seemed to be a shift away from sex-role stereotypes for both women and

men. Schein(2001),concluded that managerial stereotyping had reduced amongst women but not men. However, Powell & Butterfield( 2003) found that high masculinity but not low femininity was still associated with aspirations to top management. In view of the international research overwhelmingly concluding that androgyny and masculinity is related to women emerging as managers and assuming that Pakistans unique culture and socio-economic environment would have a minimal impact on the managerial womens gender role identity , we would expect, Hypotheses 1: Pakistani Managerial women would be more likely to be androgynous or masculine. Hypotheses 2: Managerial women classified as androgynous or masculine would be more likely to advance rapidly than feminine or undifferentiated. METHOD Procedure and Respondents Over 152 companies in Pakistans three major cities of Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad/Rawalpindi were contacted to find out if they were employing females at managerial levels. Out of these, 87 organizations informed us that women were working at managerial levels. Packets of questionnaires were sent to Head of Human Resources according to the numbers intimated. The Human Resource Department circulated these questionnaires which were all in self addressed envelopes to all women working at managerial levels in their organization. The respondents (N= 207) were a cross section of ages. 50% of the total managerial women surveyed were young women in the 21- 30 year category with the majority falling in the 25-30 year bracket signifying a growing trend among younger women in Pakistan to join the managerial ranks. 56% of the women were employed by private multinational and 24% by local companies. Almost all worked in a large

city. 48% were single and 45% married. 16% had no children. They had mostly been to English medium schools and were highly educated. Their education level ranged from Bachelors to Doctorate with 83% having a Masters or professional degree. Measures. The questionnaire was in English as English language is taught as primary medium of instruction in all universities. The predominantly close ended questionnaire contained multiple measures including two specifically designed to measure gender role identity and managerial advancement. Gender role (i.e. sex role identity) was assessed using The Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI)(Bem,1974). It was developed to measure gender roles as indicated by internalized socially desirable characteristics. It contains 60 items, 20 characteristic of femininity, 20 characteristic of masculinity and 20 characteristics of social desirability bias. Items are rated from 1 (never or almost never true) to 7 (always or almost always true). Masculinity and Femininity scores were calculated for each individual as the average of scores on the masculine and feminine items in each self description. Each individual was assigned to each of the four gender role categories, masculine, feminine, androgynous and undifferentiated. Managerial Advancement: Managerial advancement was measured using a scale used by P.Tharenou(1999).It was the average of 3 items:( a) Managerial level was measured from 1, Officer/Management Trainee to 6, CEO; ( b) Monthly salary, from 1,Rs 7,000- Rs 25,000 to 6, Rs 160,000 and above ( c ) total managerial promotions from no promotions to 4 promotions. Questions were asked on work history, specifically current designation, current salary and previous designations and previous salary. Number of promotions was derived based on work history of each individual. The three item measure of managerial career

10

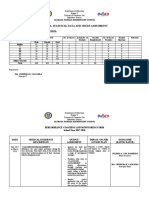

advancement was reported reliable by Tharenou(1999). The average of the three items was then split into rapid and slow advancement based on mean value. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION The first objective of this study was to investigate the gender role identity . Table 1 shows the descriptive results. As can be seen the managerial women fall into the four groups: 29%, Androgynous; 21.7%, Masculine; 22.7%, Feminine and 26.6%, Undifferentiated. Unlike studies in the developed world, our managerial women do not conform to the think manager, think male model (Schein 1996). [Insert Table 1 about here.] Although the percentage of androgynous women is higher than the other orientations, it is only by a small percentage. Non- parametric chi square test was used to test if all four categories contained the same proportion of values. This test was found to be not significant. Chi-square= 2.83, df 3, p= .418. Therefore, it was concluded that there was no dominant gender role orientation of managerial women in Pakistan. All were equally distributed. Our hypothesis was rejected that managerial women were more likely to be masculine or androgynous. Unlike the Pakistani data, the data of an Indian study( Budhhapriya 1999) of 166 public sector female managers demonstrates that 44.38% of the women were androgynous, 21.88% were Masculine; 25.63% were Feminine and 8.13% were Undifferentiated. The question that emerges as a result of the findings is why so many women in Pakistan are undifferentiated in their gender orientation. Undifferentiated individuals are suggestive of poorer socialization and limited behavioral flexibility. (Bem 1974)A possible explanation why so many of the Pakistani managerial women fell in the undifferentiated category may have to do with the unique socio- cultural environment of Pakistan. The

11

purpose for which BSRI was constructed was to assess the extent to which the cultures definitions of desirable female and male attributes are reflected in an individuals selfdescription( Bem,1979, 1048). Whereas, in the developed countries, girls and boys receive fairly similar training, in Pakistan, the girl child faces a different environment. In Pakistan, women are conditioned from childhood to give importance to the communal dimension discussed earlier. Being feminine is expected of women and women are incomplete as women if they do not demonstrate qualities of devotion, nurturance etc. This is reflected in Table 2. It illustrates a comparison of mean scores of masculinity and femininity of USA and Pakistan. An examination of the scores of masculinity and femininity of Pakistani Managerial women reveals that the femininity scores are higher for all Pakistani Managerial women. Medians were used for classification purposes into gender role orientations. The median cutoffs in our study, for the masculinity scores were 5.25 and the median cut off for the femininity score was 5.20. The median cutoffs of a study in USA of 122 undergraduate business students ( Kent and Moss 1994), for the masculinity scores were 5.3(higher than Pakistan) and the median cut off for the femininity score was 4.7( lower than Pakistan). [Insert Table 2 about here.] The high femininity scores may be reflective of our culture, where masculine women are still feminine. It is interesting to note that the mean feminine scores of both masculine women and undifferentiated women are the same. In a study ( Zhang, Norvilitis and Jin 2001), culture, specifically the Confucius philosophy in which moderation is always valued, was used as an explanation for the low scores on both items. Cultural myths shape the gender schemas of children of both genders and influence their perceptions without their being consciously aware of it. These myths are reinforced by parents, mass media, socialization and schools. Shah( 1986) states that the parental and conjugal roles have a high degree of primacy in Pakistani women and the roles of women are defined by people who have been

12

raised in a tradition of compromise and confusion. In Pakistan, females are generally kept segregated with a minimum interaction with men, who are not part of the immediate or extended family. This means that observational learning is also restricted. Females almost always attend single sex schools and colleges. Teachers usually are also of the same sex. Sports, an area where women might bring out their assertive or aggressive side is not encouraged. As a norm, most sports played in schools is mostly feminine such as netball, badminton, table tennis. The university is the first level where they deal with men, who are not part of their extended family. As a result, most women only know the feminine side of themselves. Exposure to men really occurs when they join the workforce. In order to survive in a predominantly male organizational setting, most women world over acquire male traits (Briles 1987; Madden 1987; Coppolino & Seath 1987; Gutek 1985; Kanter 1977; Miller 1976, Bell 1990). These women have adjusted to the double bind situation in which they are required both to assume male patterns of behavior and to preserve their distinctively female characteristics(Gherardi and Poggio 2001).Therefore four groups of women emerge: The masculine gender identity, who realizes the importance of the male centeredness of organizations and suppresses her femininity; the androgynous individual who recognizes the importance of the male centeredness of organizations but is not willing to suppresses her femininity; and the feminine individual who accepts her cultural conditioning and decides not to break the norms, these women have not accepted being male as part of their self identity; and the undifferentiated, who are learning how to be masculine slowly and have learnt not to be feminine. This dilemma of young womens inability to differentiate themselves based on gender identity seems plausible given the environment they have grown up, in Pakistan.

13

Age also has a role to play. The below 30 year old women are still in the process of forming their identity. They do not have the confidence to take a stance. As these women grow older and more experienced, it is conceivable that they become confident and take a stance. They learn how to handle themselves. The more they learn through successful experience, the more confident they become and the self begins to take shape. In such a scenario women, who are confident, will break the norm and decide that maleness is an acceptable part of their identity. A cross tabulation between age less than or equal to 30 years and 31 years and above, and sex-role orientation (combined) resulted in a Chi-square = 5.635, df= 1, p< .05 (Table 3).It demonstrated that women of age 31 years and above were more likely to be masculine or androgynous.( Z = 2.37, p= .009,one tailed test) [Insert Table 3 about here.] The second objective was to explore whether masculine or androgynous gender role orientation would expedite managerial advancement. The managerial advancement variable was split into rapid and slow advancement. Table 4 exhibits cross tabulations between gender roles and managerial advancement. Chi-square test of sex-role orientation and managerial advancement (slow and rapid) reported association between managerial advancement and sex role orientations, Chi-square= 8.906 with 3 degrees of freedom (p< .05). [Insert Table 4 about here.] As our hypothesis was to prove that Pakistani Managerial women would be more likely to be androgynous or masculine, the above genders were then collapsed into androgynous/masculine and feminine/undifferentiated. Table 5 exhibits the cross tabulations between combined gender group masculine/androgynous and feminine/undifferentiated. Chisquare= 4.228, p< 0.05, revealed that there was some difference in the managerial advancement of androgynous/masculine and feminine/undifferentiated managerial women.

14

The significance test between two proportions (Androgynous and masculine, Rapid advancement: N= 62) was significant. (Z = 2.06, p=0.04.) Androgynous and masculine women were more likely to advance rapidly. [Insert Table 5 about here.] In order to further explore the relationships between specific gender roles and managerial advancement, additional tests were carried out. Table 6 exhibits the mean advancement scores of the different gender orientations. [Insert Table 6 about here.] Pair wise t- test was conducted between the mean advancement scores of the different gender orientations. Specifically, the masculine women advanced faster than feminine (t= 2.851, p=.005), undifferentiated women advanced faster than feminine (t= 1.979, p=.051).There was no significant difference between androgynous and feminine womens advancement. (t= 1.443, p= .151). It was concluded that masculine and undifferentiated individuals scored higher on managerial advancement as compared to feminine and that feminine women were least likely to advance rapidly. The significance of this finding of the study is that there was no significant difference between androgynous and feminine womens advancement. This is because both feminine and androgynous women had high femininity scores. On the other hand masculine and undifferentiated gender role identity does not have an adverse affect on managerial advancement. The feminine scores for both were the same and lower than the other two categories. We can conclude that feminine women were least likely to advance rapidly. Even though society demands a feminine woman, advancement in managerial positions will be rapid for women who have suppressed their feminine side. The social identity theory argues that when status differences are clear and the value systems are wide spread, individuals

15

disassociate themselves from the low status group( women in male dominated organizations) and assimilate culturally and psychologically into the higher status group; men in male dominated organizations( Williams & Giles 1978). They have to be assertive, tough, dominant, task oriented etc. These Pakistani women, learn quickly that they have to act like men in order to survive. They also learn that they have to suppress their femininity in order to survive in a male dominated organization and in a male dominated society where being young and female brings attention to the gender. The study demonstrates that the private sector in Pakistan will give women a chance to progress if they are not feminine. LIMITATIONS and CONCLUSION This study has two limitations. Some may argue that the BSRI is an out dated measure (Ballard-Reisch and Elton1992;Wong, McCreary and Duffy 1990) or cannot be applied to all cultures. BSRI was chosen as it has been used for a number of empirical studies in the recent past(Campbell, Gillaspy and Thompson 1997; Holt and Ellis 1998; Konrad and Harris 2002).It has also been used in other cultures: Japan (Katsurada & Sugihara 1999) Malaysia ( Maznah and Choo 1986; Ward and Sethi 1986), Zimbabwae ( Wilson et al 1990), China ( Wang and Creedon 1989) and Turkey (Ozkan and Lajunen 2005). A second limitation of this study is that the sample is confined to the private sector. The public sector could reveal different findings. Regardless of the above limitations, this study is of significance because it demonstrates that it has been difficult for the managerial women of Pakistan to break away from the traditional role expectations of its society. Gender role identity occurs as a result of rearing patterns and not by hormones. It is social practice that determines gender role identity. Women usually acquire a great deal of sex role learning early in their lives. Undoing that learning process takes time, which is why, there was no dominant gender role orientation of

16

managerial women in Pakistan. All were equally distributed. Our hypothesis was rejected that managerial women were more likely to be masculine or androgynous. Gender role orientations for women in management can be overshadowed by their unique socio-cultural environments. Unlike the global literature which does not place a positive value on undifferentiated individuals, undifferentiated gender identity is not a barrier to womens managerial advancement in Pakistan. Whereas international research, focuses on masculinity as important to managerial advancement, our study demonstrates that organizations in the private sector in Pakistan will accept women with low masculinity (Undifferentiated gender identity) or high masculinity (masculine gender identity) as long as their feminine side is low. Managerial women who are feminine are least likely to advance rapidly in managerial advancement in a society which places a high value and expects its women to conform to the traditional role of their gender.

17

References Alagna, S. W. (1982). Sex Role Identity, Peer Evaluation Of Competition, And The Responses Of Women And Men In Competitive Situation, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 43: 546-554. Alvessson, M. and Due Billing,Y.(1992).Gender and Organization: towards a differentiated understanding. Organization Studies:13,12, 73-103. Ballard-Reish, D.,and Elton, M.(1992). Gender orientation and the Bem Sex Role Inventory: A psychological construct revisited. Sex Roles 27: 291 306. Bem, S.L. (1974). The Measurement of Psychological Androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 42, 2:155-162. Bem, S.L.(1975). Sex Role Adaptability: One Consequence Of Psychological Androgyny. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 31:634-643. Bem, S.L. (1979). Theory and measurement of Androgyny: A reply to Pedhazur-Tetenbaum and Locksley-Colten critiques. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 37:1047-1054. Bem, S.L. (1981). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review 88: 354-364. Bem, S.(1993). The Lenses of Gender. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. Bell, E.L.(1990). The bicultural life experience of career-oriented black women. Journal of Organizational Behavior 11: 459- 477. Bhatnagar,D.(1988). Professional women in organizations: New paradigms for research and action. Sex Roles 18: 343-355. Blee, K.M.and Tickamyer, A.R.(1995). Racial differences in mens attitudes about womens gender roles. Journal of Marriage and the Family 57: 21 30.

18

Bosak J.and Sczesny S.(2008). Am I the right candidate? Self-Ascribed fit of women and men to a leadership position. Sex Roles 58, 9-10,682-688. Brenner, O. C.: Tomkiewicz, L. and Schein, V.C. (1989).The Relationship between Sex Role Stereotypes and Requisite Management Characteristics Revisited. Academy of Management Journal 32:662-669. Brewer, N.; Mitcell,P. and Weber,N. (2002).Gender role organizational status and conflict management styles. International Journal of Conflict Management 13:1,78-94. Briles, J.(1987). Woman to woman: From sabotage to support. New Horizon Press, Far Hills, NJ. Buddhapriya,S. (1999). Women in Management. A.P.H. Publishing Corporation, New Delhi. Campbell. T., Gillaspy, J.A., Jr., and Thompson, B.(1997). The factor structure of the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI): Confirmatory analysis of long and short forms. Educational and psychological Measurement 57:118 -124. Chambers, J.M.(1999).The Job Satisfaction of Managerial and Executive Women: Revisiting the assumptions. Journal of Education for Business.(November/December): 69-74. Chow, E. N.(1987). The Influence Of Sex-Role Identity And Occupational Attainment In The Psychlogical Well-Being Of Asian American Women. Psychology of Women Quarterly11: 69-82. Claes, M.T.(1999).Women, Men and Management Style. International Labour Review 138, 4: 431-446 Coppolino, Y., and Seath, C.B., (1987). Women mangers: Fitting the mould or moulding the fit. Equal Opportunities International 6: 4-10. De Vaus, D., and McCallister, I .(1991).Gender and work orientation. Work and Occupations 18:72-93.

19

Dorbrzynski, J.(1996). Gaps and barriers, and womens careers. The New York Times, 28 February:C2. Duehr, E. and Bono, J.(2006). Men, Women, And Managers: Are Stereotypes Finally Changing?. Personnel Psychology 59:815-846. Duncan, L.E., Peterson, B.E., and Winter, D.G.(1997). Authoritarianism and gender roles: Toward a psychological analysis of hegemonic relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 23:41 49. Eagly, A.H.(1987). Sex Difference In Social Behavior: A Social-Role Interpretation, NJ: Erlbaum, Hillsdale. Eagly, A.H.,Wood,W. and Diekman, A.B.(2000). Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: a current appraisal, In Eckes,T. and Trautner, H.M.(Eds), The Developmental Social Psychology of Gender, Laurance Earlbaum Associates, Mahwah N.J. Eichinger, J., Heifetz, L.J., and Ingraham, C. (1991). Situational shifts in sex-role orientation: Correlates of work satisfaction and burnout among women in special education. Sex Role 25:425-440. Erez. M. and Earley, P.C.(1993). Culture, self-identity and work. Oxford University Press, New York. Fagenson, E.A.(1990). Perceived Masculine And Feminine Attributes Examined As A Function Of Individuals Sex Level in the Organizational Power Hierarchy: A Test Of Four Theoretical Perspectives. Journal of Applied Psychology 75: 204-211. Gherardi,S. and Poggio,B. (2001). Creating and Recreating Gender Order in Organizations. Journal of World Business 36(3): 245-259. Gianakos, I. and Subich, L.M.(1988). Student sex and sex role in relation to college major choice. Career Development Quarterly 36: 259-268.

20

Gianakos, I. (1995).The relation of sex-role identity to career decision-making self-efficacy. Journal of Vocational Behavior 46:131-143. Goktepe, J.R. and Schneier, C.E.(1989). Role of Sex, Gender Roles and Attraction in Predicting Emergent Leaders. Journal of Applied Psychology 74:165-167. Government of Pakistan.(2003). An enquiry Report on the Status of Women Employment in Public Sector Organizations. National Commission on the Status of Women. Islamabad. Pakistan. Gutek,B.A.(1985). Sex and the workplace, Jossey-Brass, San Francisco Guy, M.E, (1992). Three steps forward, two steps back-ward: the status of womens integration into public management. Paper presented at meeting of the American Society of Public Administration (ASPA), Chicago, IL. Holt, C.L., and Eltis, J.B. (1998). Assessing the current validity of the Bem Sex Role Inventory. Sex Roles 39:929-941. Human Development Report (Data 2005) UNDP available at http://hdrstats.undp.org/countries/country_fact_sheets/cty_fs_PAK.html Hussain, Neelam. Mumtaz, Samiya. & Saigol, Rubina.(eds).(1997) In Engendering The Nation-State Vol. 1, Simorgh Kanter, R. M.(1977). Men And Women Of The Corporation, Basic Books, New York. Katsurada, E. and Sugihara, Y.(1999).A preliminary validation of the Bem Sex Role Inventory in Japanese culture. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 30:641 645. Kent,R .L. and Moss, S.E.(1994).Effects of sex and gender role on leader emergence. Academy of Management Journal 37:1335-1346.

21

Konrad, A.M. and Harris,C.(2002). Desirability of the Bem Sex-Role Inventory Items for Women and Men: A comparison Between African Americans and European Americans. Sex Roles 47. Nos. 5/6. Krausz, M., Kedem, P., Tal, Z., & Amir, Y.(1992). Sex-Role orientation and work adaptation of male nurses. Research in Nursing and Health 15: 391-398. Lipsey, R. G.; Steiner, P. O.; Purvis. D. D.; Courant, P. N.(1990). Economics, Harper & Row, New York. Long, B.C. (1989). Sex role orientation, coping strategies, and self-efficacy of women in traditional and non-traditional occupations. Psychology of Women Quarterly,13:307-324. Madden, T.R.(1987).Women versus women: The uncivil business war. AMACON, New York Maznah, I., and Choo, P.F. (1986). The factor structure of the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI). International Journal of Psychology 21:31 41. Miller,J.B.(1976). Toward a new psychology of women, Beacon Press, Boston. Mumtaz, Khawar and Shaheed, Farida. (1987). Women of Pakistan. Two step forward,one step back., Vanguard books Pvt Ltd. Pakistan Ozkan, T; Lajunen, T. (2005). Masculinity, femininity, and the Bem Sex Role Inventory in Turkey. Sex Roles:Jan, 2005. Powell, G.N., Butterfield, D.A. and Parent, J. D. (2002). Gender and Managerial Stereotypes: Have the times changed? Journal of Management, 28,2:177-193. Powell, G.N. and Butterfield, D.A . (2003). Gender,Gender identity and aspirations to top management. Women in Management Review, 18, :88-96. Rosener, J.B.(1995). Americas Competitive Secret, Oxford University Press, Oxford Schein V.E , Muller R, Lituchy T, Liu J, (1996).Think manager Think male: A global phenomenon?. Journal of Organizational Behavior17:33 41.

22

Schein V.E .(2001). A global look at psychological barriers to womens progress in management. The Journal of Social Issues 57:675-688. Shah, Nasra M., and Elizabeth A. Bulatao.(1981). Purdah And Family Planning In Pakistan Interntional Family Planning Perspectives 7 (1) 35-36 Shah, Nasra M., Alam, I.; Awan, A. & Karim. M, (1986). Pakistani Woman; SocioEconomic and Demographic Profile. Pakistan Institute of Development Economics Islamabad and East West Population Institute,Hawaii. Stimpson, D., Jensen, L. and Neff, W.(1992). Cross-culture gender difference in preferences for a caring morality. Journal of Social Psychology 132:317-322. Tharenou, P. (1999). Is there a link between family structures and Womens and Mens Managerial Career Advancement? Journal of Organizational Behavior 20 No.6.(Nov):837863. Twenge, J.M. (1997). Changes in masculine and feminine traits over time: A meta- analysis. Sex Roles 36:305-325. Unger, R.K. (1992). Will the Real Sex Difference Please Stand Up? Feminism & Psychology 2: 23138. Unger, R.K. (2005). The Limits of Demographic Categories and the Politics of the 2004 Presidential Election. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 5: 15363. Unger, R.K., Draper, R.D. and Pendergrass, M.L.(1986).Personal Epistemology and Personal Experience. Journal of Social Issues 42: 6779. Unger, R.K., Gareis, K.C. and Locher, P.J. (2007). Positivism and Patriotic Militancy: The Influence of Covert Ideologies on Students Reactions to September 11, 2001. Peace and Conflict 13: 20120. Ushasree,S., Seshu Reddy, B.V., Vinolya, P.(1995).Gender, gender-role, and age effects in teacher's job stress and job satisfaction. Psychological Studies 40,2:72-76.

23

Vacha-Haasa, T., Walsh, B.D., Kapes, J. T., Dresden, J.H., Thomsom, W. A., OchosSargey, B., & Comacho, Z.(1994). Gender differences on the Value Scale for ethnic minority students. Journal of Vocational Behavior 21: 408-421. Wang, T.H., and Creedon, C,F,(1989). Sex role orientations, attributions for achievement, and personal goals of Chinese youth. Sex Roles, 20:473-486. Ward, C., & Sethi, R. R.(1986). Cross-cultural validation of the Bem Sex role Inventory: Malaysian and South Indian research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 17:.300 314. Wigfield, A., Battle, A., Keller, L.B. and Eccles, J.S.(2002). Sex differences in motivation, self concept, career aspiration and career choice: implications for cognitive development. In McGillicuddy-De Lisi,A. and De Lisi , R. (Eds) Biology, Society and Behavior: The Development of Sex differences in Cognition, Ablex, Westport,CT. Williams, J. and Giles, H.(1978). The changing status of women in society: An intergroup perspective In Tajfel, H. ( Ed), European monographs in social psychology, Academic Press, London.431-449. Williams, J. E and Best, D. L. (1982). Measuring Sex Stereotype: A Three-Nation Study, Sage, Beverly Hills, Calif. Williams, J. E., & Best, D. L.(1990), Sex and Psyche: Gender and Self viewed Cross culturally, Sage, Newbury Park, CA Wilson, D., McMaster, J., Greenspan, R., Mobyi, L., Ncube, T., & Sibanda, B. (1990). Crosscultural validation of the Bem Sex Role Inventory in Zimbabwe. Personality and Individual Differences, 11:651-656. Wong, F, Y., McCreary, D.R., and Duffy, K.G.(1990). A further validation of the Bem Sex Role Inventory: A multitrait multimethod study. Sex Roles 22:249-259.

24

Woolf, S.E. & Maisto, S.A. (2008). Gender differences in condom use behavior? The role of power and partner type. Sex roles, 58,9-10, 689-701. Zhang, J.; Norvilitis, J.M.; and Jin, S. (2001). Measuring Gender Orientation With the Bem Sex Role Inventory in Chinese Culture. Sex Roles 44, Nos.3/4: 237-251.

25

TABLE 1 Sex Role orientation of Managerial Women of Pakistan. Sex Role Orientation Undifferentiated Feminine Masculine Androgynous N 55 47 45 60 % 26.6 22.7 21.7 29

26

TABLE 2 A comparison of Mean scores of Masculinity and Femininity of USA and Pakistan Gender Role Orientation Mean Masculine Scores(USA) Masculinity Androgynous Feminine Undifferentiated 5.73 5.84 4.57 4.59 5.60 5.77 4.74 4.65 Mean Masculine Scores(Pakistan) Mean Feminine Scores(USA) 4.03 5.18 5.38 4.09 4.60 5.56 5.55 4.60 Mean Feminine Scores(Pakistan)

27

TABLE 3 Cross Tabulation of Age and Sex Role Orientation. Age 30 and Below 31 and Above Total Undifferentiated/ Feminine 57 42 99 Masculine/ Androgynous 43 62 ** 105 Total 100 104 204

(** )Proportion larger than random, p = .009

28

TABLE 4 Cross Tabulation of Managerial Advancement and Sex Role Orientation Sex Role Orientation N Androgynous Masculine Feminine Undifferentiated Total 36 19 34 33 122 Slow % 29.5 15.6 27.9 27.0 100 N 24 25 12 21 82 Rapid % 29.3 30.5 14.6 25.6 100

29

TABLE 5 Combined Group Sex Role Orientation and Managerial Advancement Sex Role Orientation Managerial Advancement Slow (Obs) Andro/Masc Femin/Undiff 55 67 122 (** )Proportion larger than random, p = .04 Managerial Advancement Rapid (Obs) 49(** ) 33 82

30

TABLE 6 Mean Advancement Scores of each Gender Role identity of Managerial Women Of Pakistan. Sex Role Orientation Undifferentiated Feminine Masculine Androgynous Mean 2.1604 1.8043 2.3177 2.0668 S.D .9173 .8789 .8291 .9837

31

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Operations ManagementDocumento290 pagineOperations Managementrockon60594% (104)

- Persuasive EssayDocumento5 paginePersuasive Essayapi-33130822571% (7)

- Bonn, I 2001Documento11 pagineBonn, I 2001espernancacionNessuna valutazione finora

- PROPOSALDocumento2 paginePROPOSALShaina Kaye De Guzman100% (2)

- Lit ReviewDocumento3 pagineLit ReviewAvni ChawlaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 Lit ReviewDocumento17 pagine1 Lit ReviewKairn MartinNessuna valutazione finora

- The Literature Review Working WomenDocumento5 pagineThe Literature Review Working Womenpawan luniwalNessuna valutazione finora

- Women SteriotypeDocumento31 pagineWomen Steriotypebublystar4303Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Qualitative Study of Pakistani Working Women's Advancement Towards Upper Level Managerial PositionsDocumento14 pagineA Qualitative Study of Pakistani Working Women's Advancement Towards Upper Level Managerial PositionsSyed Mubaser RizviNessuna valutazione finora

- CHP 2Documento21 pagineCHP 2Nina AzamNessuna valutazione finora

- RetrieveDocumento10 pagineRetrievewagih elsharkawyNessuna valutazione finora

- MPOBDocumento12 pagineMPOBankidapo78Nessuna valutazione finora

- Gender-Based Discrimination Faced by Females at Workplace: A Perceptual Study of Working FemalesDocumento7 pagineGender-Based Discrimination Faced by Females at Workplace: A Perceptual Study of Working FemalesMansi TiwariNessuna valutazione finora

- Patriarchal Beliefs, Women's Empowerment, and General Well-BeingDocumento13 paginePatriarchal Beliefs, Women's Empowerment, and General Well-BeingRashmi MehraNessuna valutazione finora

- Importance of The Study To ResearcherDocumento4 pagineImportance of The Study To ResearcherEmmanuel Christopher VillapandoNessuna valutazione finora

- Eagley Role Congruity TheoryDocumento26 pagineEagley Role Congruity TheoryCristina PetrişorNessuna valutazione finora

- 301-N10013 Attitude Towards Women On Managerial Position in PakistanDocumento5 pagine301-N10013 Attitude Towards Women On Managerial Position in PakistanAnoosha KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Budworth, M.H., & Mann, S. (2010) - Becoming A LeaderDocumento10 pagineBudworth, M.H., & Mann, S. (2010) - Becoming A LeaderGabriela BorghiNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender and LeadershipDocumento5 pagineGender and Leadershipsushant tewariNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender Disparity in Pakistan-ProjectDocumento5 pagineGender Disparity in Pakistan-ProjectverdaNessuna valutazione finora

- Women in ManagementDocumento8 pagineWomen in ManagementYus NordinNessuna valutazione finora

- Who Does She Think She Is Women Leadership and The B Ias WordDocumento18 pagineWho Does She Think She Is Women Leadership and The B Ias WordАлександра ТарановаNessuna valutazione finora

- Stahl, Günter K., Edwin L. Miller, and Rosalie L. TungDocumento1 paginaStahl, Günter K., Edwin L. Miller, and Rosalie L. TungPr BansalNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender Issues at WorkplaceDocumento35 pagineGender Issues at WorkplaceNilushi FonsekaNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender Disparities and Workplace Traumas of Women EmployeesDocumento5 pagineGender Disparities and Workplace Traumas of Women EmployeesJenifer JayakumarNessuna valutazione finora

- CCHRM Paper FinalDocumento18 pagineCCHRM Paper FinalPti PakistanNessuna valutazione finora

- Ge Elect 4 Gender and SocietyDocumento8 pagineGe Elect 4 Gender and SocietyChristine IbiasNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapt 1 NugwaDocumento7 pagineChapt 1 Nugwaoluwasegunnathaniel0Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2000 Women Civil Servants and Transformational Leadership in BangladeshDocumento9 pagine2000 Women Civil Servants and Transformational Leadership in BangladeshNazmul HassanNessuna valutazione finora

- Women's Autonomy in The Context of Rural PakistanDocumento22 pagineWomen's Autonomy in The Context of Rural Pakistantech damnNessuna valutazione finora

- A Comparative Study Between Men and Women Managers Management StyleDocumento12 pagineA Comparative Study Between Men and Women Managers Management StylefaridpangeranNessuna valutazione finora

- Review of Related Literature: Gender StereotypesDocumento34 pagineReview of Related Literature: Gender Stereotypesalphashane Flores100% (1)

- Women and Leadership: Transforming Visions and Current ContextsDocumento12 pagineWomen and Leadership: Transforming Visions and Current ContextsMoeshfieq WilliamsNessuna valutazione finora

- Herrera Et Al. (2012) - Gender On LSDocumento12 pagineHerrera Et Al. (2012) - Gender On LSHansNessuna valutazione finora

- Attitudes Toward Gender Roles in Young AdultsDocumento16 pagineAttitudes Toward Gender Roles in Young AdultsAmna ZeeshanNessuna valutazione finora

- Men's Perspective On Changing Role of WomenDocumento21 pagineMen's Perspective On Changing Role of WomenNishtha NayyarNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender RolesDocumento12 pagineGender RolesYULIZA GARRO MENDEZNessuna valutazione finora

- Project - Gender Stereotypes in Pop CultureDocumento20 pagineProject - Gender Stereotypes in Pop CultureEla GomezNessuna valutazione finora

- Women Empowerment: A Study Based On Index of Women Empowerment in IndiaDocumento16 pagineWomen Empowerment: A Study Based On Index of Women Empowerment in IndiakumardattNessuna valutazione finora

- The Influence of Gender On The Performance of Organizational Citizenship BehaviorsDocumento20 pagineThe Influence of Gender On The Performance of Organizational Citizenship BehaviorsAdriana NegrescuNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender Perspectives of Indian Family (p1 - p2)Documento10 pagineGender Perspectives of Indian Family (p1 - p2)shubham singhNessuna valutazione finora

- Male Perspective On Construction of Masculinity IsDocumento10 pagineMale Perspective On Construction of Masculinity IsIndrashis MandalNessuna valutazione finora

- An Analysis On Women Empowerment Programs in India: Dr. M. S. RamanandaDocumento6 pagineAn Analysis On Women Empowerment Programs in India: Dr. M. S. RamanandaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Summary, Findings, Conclusions, and RecommendationDocumento7 pagineSummary, Findings, Conclusions, and RecommendationChristine VenteroNessuna valutazione finora

- Priola 2004 TSEDocumento13 paginePriola 2004 TSEANDRÉS ALEJANDRO NÚÑEZ PÉREZNessuna valutazione finora

- Ali Et Al, 2011 Gender Roles and Their Influence On Life Prospects For Women in Urban Karachi PakistanDocumento10 pagineAli Et Al, 2011 Gender Roles and Their Influence On Life Prospects For Women in Urban Karachi PakistanAyesha BanoNessuna valutazione finora

- AnswerDocumento10 pagineAnswerSHET YEE CHINNessuna valutazione finora

- EJ1159908Documento10 pagineEJ1159908Venice Lorraine Azarcon RebarterNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Paper On Gender Discrimination in PakistanDocumento7 pagineResearch Paper On Gender Discrimination in Pakistangw15ws8jNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender and Leadership Aspiration: Interpersonal and Collective Elements of Cooperative Climate Differentially Influence Women and MenDocumento14 pagineGender and Leadership Aspiration: Interpersonal and Collective Elements of Cooperative Climate Differentially Influence Women and MenHussain khawajaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Problem and Its ScopeDocumento17 pagineThe Problem and Its ScopeChristine VenteroNessuna valutazione finora

- Ajanta Gen-Nov-18 GenderIdentityDocumento11 pagineAjanta Gen-Nov-18 GenderIdentityDBRANLU StudentsNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender ReviewDocumento5 pagineGender ReviewAsma ShoaibNessuna valutazione finora

- Component Dimensions of Happiness An Exploratory StudyDa EverandComponent Dimensions of Happiness An Exploratory StudyNessuna valutazione finora

- Womens Empowerment 2 Jan 2003Documento39 pagineWomens Empowerment 2 Jan 2003shradhaNessuna valutazione finora

- COMMFerence ProposalDocumento13 pagineCOMMFerence ProposalMichelle CornejoNessuna valutazione finora

- Jyrkinen - Women Managers, Careers and Gendered Aging 2009Documento11 pagineJyrkinen - Women Managers, Careers and Gendered Aging 2009Aytaç YürükçüNessuna valutazione finora

- Women LeadershipDocumento10 pagineWomen Leadershipsyph218Nessuna valutazione finora

- Leadership Styles: Gender Similarities, Differences and PerceptionsDocumento15 pagineLeadership Styles: Gender Similarities, Differences and PerceptionsRahelNessuna valutazione finora

- A Review of Women Identity and EmpowermentDocumento1 paginaA Review of Women Identity and EmpowermentAlegría Vargas RampónNessuna valutazione finora

- Beyond The Glass Ceiling An Exploration of The Experiences of Female Corporate Organizational Leaders in GhanaDocumento19 pagineBeyond The Glass Ceiling An Exploration of The Experiences of Female Corporate Organizational Leaders in GhanaAishwarya MotwaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample Research ProposalDocumento26 pagineSample Research ProposalMoris MarfilNessuna valutazione finora

- Monetary Policy Statement: State Bank of PakistanDocumento42 pagineMonetary Policy Statement: State Bank of PakistanScorpian MouniehNessuna valutazione finora

- The Juran Trilogy: Edit Cost of Poor Quality Cross-Functional ManagementDocumento1 paginaThe Juran Trilogy: Edit Cost of Poor Quality Cross-Functional ManagementScorpian MouniehNessuna valutazione finora

- Banks: Possible Impact of Sharper Than Eyed DR Hikes: Morning BriefingDocumento2 pagineBanks: Possible Impact of Sharper Than Eyed DR Hikes: Morning BriefingScorpian MouniehNessuna valutazione finora

- Porters Five Forces DiagramDocumento1 paginaPorters Five Forces DiagramabollatiNessuna valutazione finora

- 12 Cross Cultural CommunicationDocumento19 pagine12 Cross Cultural CommunicationScorpian MouniehNessuna valutazione finora

- Correlation AnalysisDocumento7 pagineCorrelation AnalysisScorpian MouniehNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 2Documento22 pagineUnit 2Scorpian MouniehNessuna valutazione finora

- Tools of Research (Interview and Observation)Documento38 pagineTools of Research (Interview and Observation)Scorpian MouniehNessuna valutazione finora

- Lecture 1Documento25 pagineLecture 1Scorpian MouniehNessuna valutazione finora

- Topic 6: Experimental DesignDocumento17 pagineTopic 6: Experimental DesignScorpian MouniehNessuna valutazione finora

- Keyboard Shortcuts For Special CharactersDocumento7 pagineKeyboard Shortcuts For Special CharactersScorpian MouniehNessuna valutazione finora

- RMT Topic 5Documento17 pagineRMT Topic 5Scorpian MouniehNessuna valutazione finora

- CH 08Documento30 pagineCH 08نور الدنياNessuna valutazione finora

- CH 01Documento65 pagineCH 01Scorpian MouniehNessuna valutazione finora

- Topic 7 RMTDocumento26 pagineTopic 7 RMTScorpian MouniehNessuna valutazione finora

- Ch. 15 Capital StructureDocumento69 pagineCh. 15 Capital StructureScorpian MouniehNessuna valutazione finora

- Build A High Performing TeamDocumento12 pagineBuild A High Performing TeamDóra NagyNessuna valutazione finora

- The Three Faces of DisciplineDocumento4 pagineThe Three Faces of DisciplineAna MurtaNessuna valutazione finora

- An - Introdution To Husserlian PhenomenolyDocumento254 pagineAn - Introdution To Husserlian PhenomenolyRafaelBastosFerreiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Before I Blame Myself and Feel GuiltyDocumento4 pagineBefore I Blame Myself and Feel GuiltyLucy FoskettNessuna valutazione finora

- Eric Ed300391 PDFDocumento39 pagineEric Ed300391 PDFanisafebristiNessuna valutazione finora

- Neuromarketing Research in The Last Five Years A Bibliometric Analysis Interessante para ArtigoDocumento37 pagineNeuromarketing Research in The Last Five Years A Bibliometric Analysis Interessante para ArtigoCarlos DiasNessuna valutazione finora

- NAtural Happiness PDFDocumento29 pagineNAtural Happiness PDFAlberto FrigoNessuna valutazione finora

- Name: - Richardo Lingat - Course/Yr/Section: BSED EN 1-1 Date: - ScoreDocumento2 pagineName: - Richardo Lingat - Course/Yr/Section: BSED EN 1-1 Date: - ScoreLingat RichardoNessuna valutazione finora

- End-Of-Course Action Plan in SeameoDocumento6 pagineEnd-Of-Course Action Plan in SeameoJune Econg100% (10)

- Exercise Bosah Ugolo-CompleteDocumento3 pagineExercise Bosah Ugolo-CompleteMelania ComanNessuna valutazione finora

- School Statiscal Data and Needs AssessmentDocumento46 pagineSchool Statiscal Data and Needs AssessmentAileen Sarte JavierNessuna valutazione finora

- MID Test SLA Riko SusantoDocumento3 pagineMID Test SLA Riko Susantoriko susantoNessuna valutazione finora

- Patrick Henry Lesson PlanDocumento2 paginePatrick Henry Lesson Planapi-273911894Nessuna valutazione finora

- Theories and Principles Dela Cruz TTL BSE Eng 3Documento32 pagineTheories and Principles Dela Cruz TTL BSE Eng 3Allen BercasioNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 1 PerDev Assess Aspects of Your DevelopmentDocumento15 pagine2 1 PerDev Assess Aspects of Your DevelopmentPrimosebastian TarrobagoNessuna valutazione finora

- Daniel EthicsDocumento10 pagineDaniel EthicsDan FloresNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample RRL For In-House ReviewDocumento2 pagineSample RRL For In-House ReviewAeksio DaervesNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 4 - Leading & DirectingDocumento45 pagineModule 4 - Leading & DirectingJanice GumasingNessuna valutazione finora

- 15142800Documento16 pagine15142800Sanjeev PradhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Ranjan - Lessons From Bauhaus, Ulm and NID PDFDocumento15 pagineRanjan - Lessons From Bauhaus, Ulm and NID PDFEduardo DiestraNessuna valutazione finora

- Principles of Teaching 1: A Course Module ForDocumento41 paginePrinciples of Teaching 1: A Course Module ForLiezel Lebarnes50% (2)

- 15 Child PsychologyDocumento46 pagine15 Child PsychologyVesley B Robin100% (2)

- Ell InterviewDocumento9 pagineEll Interviewapi-259859303Nessuna valutazione finora

- CSTP 6 Vernon 4 11 21Documento9 pagineCSTP 6 Vernon 4 11 21api-518640072Nessuna valutazione finora

- MLI 101:information, Communication and SocietyDocumento43 pagineMLI 101:information, Communication and Societypartha pratim mazumderNessuna valutazione finora

- Planning Goals and Learning OutcomesDocumento18 paginePlanning Goals and Learning OutcomesNguyễn Bích KhuêNessuna valutazione finora

- Edu WKP (2019) 15Documento109 pagineEdu WKP (2019) 15Bruno OliveiraNessuna valutazione finora