Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Wild Gardens by Dian Marino - Selections

Caricato da

EstoyLeyendoDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Wild Gardens by Dian Marino - Selections

Caricato da

EstoyLeyendoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

art,

education,

and the

culture of

resistance

di

rna

EDUCATION / ART I MEDIA

1M

ARNLNO: WILD GARDEN IS NQT ABOUT GARDENING.

It is, rather, a wild and woolly book about the

cultivation of learning, base-d on author and artist

dian marino's lifelong experiences in education, It is about

the roots of teaching, the nurturing and production of knowledge, and challenges to

"basic assumptions" and "common sense."

The book is also about making mistakes and learning from them. It is about

opening up new spaces for resistance and disrupting the habits of oppression, about

how writingand art can spark subversive thoughts and creative action. And the final

chapter, 'White Flowers and a GrizzJy Bear," is a moving reflection on the lessons of

dian marino's own terminal illness and her <;:ommitment to larger struggles ..

Wild Garden combines dian marino's writings and personal reflections. art and

graphic images. and teaching tools to convey a dynamic approach to partidpatory

learning. With over fifty pieces of art. this beautifully produced book will delight,

confront, and occasionally perplex (it is a wild garden, after all) readers who question

received ideas about living, learning, and growing together.

-Dian marino categorically r e ~ the disciplining of the disciplines.

She challenges us to reject binaries, engage with paradox, and cross boundaries.

Her pedagogical insights are both visionary and in the moment -

Unda Briskin, Women's Studies, York University

"This is a bmrthtaking offering of ideas and images that e ~ r y mucator

will cherish and use. -

Budd L Hall, chair, Adult Education and Community Dtvelopment,

Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE)

D

ian marino, a visual artist, actiVISt. educator, and storyteller extraordinaire, was

a professor in the Faculty of Environmental Studies. York University, Toronto.

She died in January 1993.

r ---";;;;;;;;;; ., - - , ~ -

; ISBN 1-89 63S7-13-X

between=thedines

Retail Price .l!. .. J...i.r...r.:r.. ..

Review Copy ................. .

Complimentary ;:'opy ........... .

Desk COP'l ...... . ......

E"am ( Or)y

wild garden

~

~ d ian and I grew a vegetable garden once. It was in a meadow on top of a

~

f .:J6 hill. We planted a small area with all sorts of things and carried the

. water up the hill in buckets. Within a very short time we had all sorts of things

. sprouting uP. and just as qUickly as things sprouted the rabbits would eat

.' them. We developed a wonderful solution to this problem. Since we had planted

on the land that was used by the rabbits in the first place. and since the rabbits obviously

needed the food, we decided to plant twice as much so that there would be enough for

all of us.

dian and I were really pleased with our approach, and when things sprouted up

again we found that the rabbits were also quite pleased-twice as pleased We ended up

with no vegetables, but with a lot of time together, laughter, and a good story.

- Chuck Marino

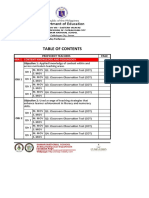

Contents

Preface and Ackno-wledgernents ..... xiii

Introduction ........................... 1

Robert Clarke and Chris Cavanagh, with Ferne Cristall

An opening glimpse of the life, work, and influence of dian

marino-of what she called the "rain forest of moveable relations"

that made up her personal history-considering the background

and the nature of her work as educator, artist , and community

activist.

L Landscape for an Easily Influenced

Mind: Reflections on My Experience

as an Artist and Educator .............. 19

Dian considers her own formation as an artist and educator working for

social change and challenges her audience to reflect on the patterns of their

own social construction. Wi th a little help from Antonio Gramsci and the

idea of "cracks in consent," combined with a purposefully misquoted Bertolt

Brecht and Nicaraguan poetry, she explores the intimate connections

between critical thinking, creativity, and art. From a paper delivered in July

1989 to an Adult Education and Art Conference, Oxford University.

2.Thoughts on Teac h i ng and

Learning ... ........ . .. . . . .... . .. 4 3

Emphasizing a feminist perspective, di an argues t hat teachers

must be open to challenging themsel ves if they i ntend to

challenge their students. She considers the teachi ng val ue of

making mi stakes, the importance of uncovering hidden

connections t hat serve those in power. and the inspi rat ion of

collective and partici patory dreaming. Based on excerpts from

an intervi ew by Annemarie Gallaugher, 1987.

3.Willovvdal e Worldvievv:

From old Mold to a

Winter Poem ... . ... .. . . . . 5 7

A visual explorati on of everyday domestic life iust

outside of Toronto, loosely mixed with dian's

refl ections on art, teaching, and living in thi s world.

Dian produced these silk-screens of such t hings as

old mould, a bird on a colander. a stove top,

flowers with an ashtray, and a window frame in the

late 1 960s and earl y 1970s: a femi ni st honouri ng of

the ordinary, an arti st playing with space and the

spaces in between.

Drawing f r o m Action for A ction:

Drawing and DiscuSSion as a Popular

Researc h Tool .. . . . .......... . . ... .. .. . ... ... . ... 61

Dian offers provocative and practical exercises on how to assess and use

drawing as a tool for cri t ical reflection and action. Starting from a theoretical

framework influenced by Brazi li an educator Paulo Freire, she considers the role

and function of participatory research and critiques individually based research.

The discussion ranges from exploring a McDonald's restaurant "participatory"

advertiSing campaign to looking for ways of demystifying the production of art.

Ori ginally published as "Worki ng Paper No.6" by the Participatory Research

Group, Toronto, 1981.

9 . Obstac les to Speaking Out .. . 89

~

....

.. ....

"';. ...

When dian presented this paper she was in t he process of

taking a closer look at participatory research workshops that

had resulted in the producti on of alternati ve educational

materials. The work had led her into media st udy and an

analysi s of t he all-pervasive corporate control of adverti sing,

which brought her back to McDonald's and the company's

myst ique of participation. Originally presented to the

International Investigative Forum of Participatory Research,

Ljubljana, Yugoslavia, April 12-22, 1980.

6. Re:fram.ing: H e gem.ony and Adul t

Education Pract i ces . ... ... .. .... . .. 103

As a follow-up to "Obstacles to Speaking Out. " dian begi ns by asking, "How do we

know i f we' re engaged in producing trul y emancipatory materials, or if we' re only

reproducing coloni zed patterns?" Adult educators (herself included) are often i n a

precarious position: working to avoid messi ness and flatten conflict in order to

workable results. Her focus becomes "re:framing" as she reject s the

metaphor of the discovery of knowledge in favour of t he construction of knowledge, with

students and teachers worki ng together Origi nally presented to the Conference on

University Teaching and Research in t he Education of Adults, fifteenth annual

conference, University of Leeds, England, 1984.

7. Reveal i ng Assum.ptions:

Teachi n g Participatory

Res e a rc hers .. . ... . ... .... 119

Dian discusses her fi rmly held belief that participatory researchers

must learn to become mutual teachers/learners and leaders/partic-

ipants. She describes her own discomfort with the idea of herself, as

teacher, lurking behind a bush and jumping out when someone "gets

it right" and with the paradox of offering a course on "resistance" and

then being expected to work at managing, cont rolling, that same

resistance in the classroom Based on an interview done by Joanne

Nonnekes, Toronto, 1990.

colour insert fol/owing p.12S

Drealn Horse, MooSe Balls, and An

arth Blanket

A selection of dian's silk-screen, watercolour, and paper collage art

that spans over three decades, with intermingling quotations from

the text.

~ ~ " '. ~ ~ .. ,

".' ... , . ~ " .:

8. White Flowers and a Grizzly Bear:

Living with Cancer ................ . . 14S

Dian wrote this article not long after she had learned that her breast cancer had

spread to her bones. She describes the sense of loss of control and the

disempowering effects of trying to reflect on and then write about the disease,

given the prevailing social attitudes-and militaristic metaphors-and the varied

responses she received from those around her. Nami ng the pain was key; only after

dian was able to name her pain could her almost irrepressible humour return

Originally published in Tlie New Internationalist , August 1989.

Notes .. .............................. .... ......... ISS

The Contri utors ....... ...... . ...... ..... 160

Introduction

Robert Cl arke and Chris Cavanagh,

wit h Ferne Crist a ll

D

ian marino loved a wild garden. In the spring of 1992, a few

months before she went into t he hospital for the last time. dian

told us a story about her backyard and her dog, Bear. You have to know

that in the last few years dian's postage-stamp-size backyard on Clinton

Street in downtown Toronto had become her heali ng cent re, her meeting

place, a workplace, and a place of meditation. Her small wooden deck

just off the back of the house was covered with century-old grapevines

and plants, but sti ll had plenty of room for Sitting and relaxing in t he

shade. The small area beyond the deck was cluttered (purposefully) with

whirring and tinkling mobiles and gizmos. There was a wild garden off to

one side-leaving just enough space for dian to stand and chat with a

neighbour-and a stone path with grass on either side leading to a

back-lane garage.

Dian's cancer had taken a turn for the worse in the spring of

1992, and she told us about a problem she was having with Bear. She felt

too weak to take the dog for regular walks, and Bear had started digging

holes in t he backyard lawn and garden. spraying up soil everywhere. as a

dog left on his own is wont to do-especially in stressful times. The yard

was getting t o be a mess, and dian didn't have the energy to fill the

holes and patch up the grass. But she found an elegant, easy solution:

she bought a bunch of new plants and plopped them down into the dog

hol es.

As usual. dian told this story with a laughing voice: laughing at

her dog, at herself, and at the world in general-a world that she knew

didn't particul arly care for the idea of ani mals di gging hol es in "cultured"

backyards. In many ways the story is typical. It is about finding a way of

coping, of seeing problems as creating new possibilities It shows a

~ . \,

2

woman finding creat ivity in t he ordinary and deli ght in breaking rules-

in this case rules about gardens. about animal behaviour. and about how

people should "normally" respond t o both health and dog probl ems It

shows dian's ability to stand outside of herself and laugh at herself-a

special gift. i ndeed.

Like wind-borne polien. dian marino drifted across natural and

constructed boundaries. She was-and i s-hard t o pin down. categori ze.

encapsulate. She was not only daughter. wife. mother. and friend. but

also arti st. storyteller. and "internat ionally known" educator (as t he press

reports put it)--criticai educator. popular educat or. adult educat or She was

university professor, popular culture worker, sociali st, feminist, environ-

mentalist. community activist. academic theorist ... Stop! The "ist's" are

taking over here as identi fi ers. And. really. it all seems much t oo seri ous.

Because dian was also a humorist. even during t he time when she had

become "a woman living wi th cancer."

In fall 1992 in her Sunnybrook Hospital room. when some

friends came t o visit and lined up neatly at t he foot of her bed. dian got

a burst of deli ght from their appearance "What beautiful colours! Did

you guys co-ordi nate your clot hes for thi s visi t ? Did you organize t his?"

she asked. Then came t he educator in her: "You've got to t ake care of the

small things. because the big things are really all fucked up."

In her many roles and in her art. lectures. conversations, and

storytelling dian operated within what she called a "rain forest of

moveable relations." And as there is more in a rain forest t han can be

humanly known, so too there is more to dian. She would critique

capitalist relations of production but spend Saturday mornings on mad

shopping sprees in a suburban lkea emporium. She would write sharpl y

about the culture and corporate piracy of McDonald's but was always

going into t he chain's outlet s and coming out with t he latest Speci al

Offer plastic toy of the week. which she'd then give away to a friend's kid.

You got the feeling she went to McDonal d's not to study it or even t o eat

burgers-though she would half-guiltily admit to enjoying the odd Big

Mac-but to get the toys. She also sai d they could be relied on for their

clean bathrooms.

In her life and work dian was the sort of person that Italian

Marxist and activist Antonio Gramsci-one of her favourite theorists-

Wild Garden

referred to as an "organic intellectual. " British t heorist Terry Eagleton has

described a type of "organic intellectual " who, like dian, goes against the

grain of society "Such a figure is less a contemplative thinker, in the old

idealist style of the intell igentsia, than an organizer, constructor,

'permanent persuader', who actively participates in social life and helps

bring to t heoretical art iculati on those positive poli tical currents already

contained within it. '" Thi s organi c intell ectual is on the front-lines of the

struggle against whatever makes up the prevailing "hegemony" (another

Gramscian term that, as we shall see, was a key concept for dian) In her

case she would work at trying t o make visible, in unique and wonderful

ways, what she called the "hidden cracks in our consent " to oppression

and at forging the often difficult but so necessary "transition from

consent t o resi stance."

Dian marino's formation as an artist and educator owed much to the

activism of the 1960s She was born Dian Coblentz in 1941 and raised in

Milwaukee. Later on she recalled

I grew up with the noti on of myself as an artist. and I also felt I

had strong social obli gations. 1 worked my art, to the degree that

I could, into my social realities. Yet as 1 became more involved

with participator! research and became more expl icit about

looking at poli tics and economic realities as part of the cultural

context , I think I began to understand what I was doing

intuitively and to recognize that it was a resistance, a very

important kind of resistance.

A part of my personal family background has been

working class, but it was a mixed family, because educationally

my mother went to university and my father didn' t-so it both

was and wasn't a working-class family 1 think there was a lot of

experiential and lived family hist ory that had me feeling li ke 1

wasn't like everyone else, and left me feeling a little bit ill at

ease-whi ch may seem funny when people see the way 1 dress. It

seems hard for them to believe that I reall y want t o be accepted.

or be part of the norm. But 1 do--l think it's about coherence. I

want to have a sense of rootedness, of history, of knowing where

I'm goi ng.

2

Introduction

3

4

For most of her life dian worked simultaneously as a teacher and a

student. In the early 1960s she took art , art history, and English courses,

and discovered radical politics, at Immaculate Heart College in

California. One of her teachers there was Corita Kent , an artist with her

own inspiring, gift ed wildness. Kent became one of dian's major artistic

and educational influences! During dian's time at the college she met

Chuck Marino, and they married in 1964 (eventually having two

daughters, Sara and Jenny).

Over the next thirty years dian taught in institutions at almost

every level. from primary school through high school to university

postgraduate studies. But she also taught outside instit uti ons Her

students included factory workers in Finland; Villagers in France; slum

dwellers and scavengers in fndonesia; Native Americans and university

professors in the United States; community workers in Venezuela; adult

educators in Chile and Thailand; and corporate execut ives, civil servants,

union leaders, underground immigrant workers, and homeless women in

Canada. The list could go on and on.

After a stint teaching at an experimental school in inner-city Los

Angeles (1964-65) she and Chuck spent a few years teaching and learning

in Edinburgh, Scotland, where dian taught at the very real school that

Muriel Spark's fictitious Miss Jean Brodi e had served so well in her

prime. In Edinburgh Chuck got notice that he was being drafted into the

U.S army-which meant. of course, the distinct possibility of fighting in

the escalating Vietnam War. They refused the invitation and moved to

Canada. Chuck got a teaching job at a relatively new institution, York

University (founded in 1959 as a small affiliate of the Uni versity of

Toronto, it got its independence in 1965). Dian also began working at

York, first as a tutor in 1971, then as a teaching assistant. part-time

lecturer. and later as course director in the Department of Psychology at

York's Atkinson College

She also worked on postgraduate degrees in environmental

studies at York University (1974) adult education at the University of

Toronto's O.I.S.E. (Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, 1977, 1984)

"My Ph.D. committee warned me that one of my problems was I wanted

to learn:' she said in an interview' She also wanted to transform the

nature of learning. She once altered the environment of Envi ronmental

Studies by creating giant "tubes" made of clear plastic sheets with all

sorts of stuff-artwork, messages, declarations, celebrations, critiques,

greetings-stuck onto the inside of them and hanging down all over.

Wild Garden

Students, professors, and staff had to walk through t he tube-lined halls

to get t o offices and cl assrooms.

By 1984 she had become a professor in York University's Faculty

of Environmental Studies-though it was never easy for her worki ng in

the belly of the beast, as she said: "I think most of the education that

happens in uni versities is domesticating and maintains current political

relations It's not really aimed at changing very much. That's not my goal

In fact I would like to change things quite deeply and dramatically'"

At the very same ti me, and perhaps most essentially, she had

become deepl y involved, outside the university setting, in the adult

educati on movement (including literacy and participatory research),

internati onal solidarity, anti-psychiatry/mental health organizing, and

environmental education. She was a founder. with Budd Hall and Ted

Jackson, of the Partici patory Research Group IPRG), an organization

linked to the International Council on Adult Educati on and springing

from a criti que of the domi nant research met hods of the day The PRG

supported activist research by

women garment workers, Nat ive

band councils, immigrant youth

groups, and trade union health and

safety committees. As a result. for

instance, in 1978-80 dian was

teaching English t o new immigrant

workers in Toronto workplaces in a

collaboration between labour unions

and plant management. boards of

education and community organi-

zations. The classes were held in

factory cafet erias.

She also, always, did her

art-provocative, colourful work, a

rich and playful blend of socially

committed and personal expression

The art-sometimes produced collec-

tivel y and sometimes on her own One flower holding it all together

-challenges traditional relationships between people, nature, and

media. "To create means to relate," her teacher Cori ta Kent wrote. "The

root meaning of the word art is to fit together and we all do this every day.

Not all of us are painters but we are all artist s. Each ti me we fit thi ngs

Introduction

6

;

together we are creati ng-whether it is to make a loaf of bread. a child. a

day. "" As a teacher and an artist dian al ways seemed to find ways of

breaki ng down establi shed ways of seeing things in order to find

divergent angles. to open up new spaces for resistance-translated into

art. for instance. as "the spaces between."

The articl es in this book were written. or spoken (two of t hem are based

on interviews, and a couple more delivered at conferences), in a span of

intense activity between 1980 and 1990. They are both autobiographical

and about autobiography. They are about teachi ng in university and

community settings, about methodology and technique. They are about

using art for education and action, taking risks and problem-solvi ng,

shi fting "frames," and recognizing and reorganizing the structures

that govern our everyday lives. They are about rethinking, or

re:framing, everyday life and the rol es of working and

teaching; about integrati ng creati vity, intui tion, and

ideology in art, learning, and action.

In some ways t he art icles reflect changes in the

educational thought of the time; in how to do poli tical

education. They reveal a process of changing

methodology in the practice of criti cal or political

education. In doing t his they refl ect changes within the

wider radical education movement: the shift in the

1970s away from teachers and acti vists (consciously or

unconsci ously) thinking they had the answers to how the

world works. and that they had only to work at finding the best

way of leading students or participants towards those answers; and

moving towards an integrat ed stance of seeing learning-and

resistance-as a jointly negotiated process on the part of teacher and

learner. Dian marino saw femi nist and postmodern thought as friendly

aids to her critique of the tidier facilitation methods she had bought into

with a certain amount of discomfort. This particular pedagogy involved

messiness and disruption- "disruptively connected," dian called it-but

could ultimately lead to more fruitful learning, and possibly to new

directions for both teacher and student. Still, she also loved to give a

good lecture, one of the most traditional pedagogical techniques.

although the lectures were distinctly conversational in tone.

Wild Garden

Problem-solving in imaginative or creative ways is a constant

theme of this work But the problem-solving did not happen in isolation

from a social setting. It was not something t hat was mystical or "new

age" or that relied sol ely on logical analysis Much of it focused on

metaphor and "The language of t ransformati on and imaginati on is

extremely important to me," she says "As art ist I feel I've committed

a lot of my life to working to have people imagine and express

alternative visions. As we're going through a process of decolonizing,

we're also expressing transformative visions, alternati ves, trying to make

our worlds and our contexts healthier, better places to be"

The changes in dian's visual art run hand-in-hand with her

practice of educati on and activism. Some pieces (like "Songs of struggle

and celebration') were collective productions; some were done for

political projects, meet i ngs, events. Some were si mpl y the work of a

political ly engaged arti st sifting through the complexities and contra-

dictions (and the funny side) of life. Although she drew, illustrated, and

painted extensively, di an worked primarily i n silk-screening (serigraphy)'

a print-maki ng process using a fine-mesh silk-screen through which

paint is forced onto paper (see "Landscape for an Easily Influenced

Mind") Screen-printi ng, one of t he newest of t he graphic arts-dating

back only t o the beginning of the century-caught on particularly with

artists and activist s from the 1960s on They rea li zed it was an

inexpensive and way of making multicolour prints on paper and

cloth, and it required a minimum of equipment and machinery. (Today

you can find beginners' si lk-screening kits i n t he children's sections of

stationary and art supply stores.)

Dian used silk-screening to deal with issues of politics, power,

gender, the environment. or simply to exalt, disparage, celebrate, or

complain about the structures of "everyday life"-Iooking for the

aesthetic in the everyday the "everyday spectacl es." While some popul ar

art was playi ng with pi eces of daily life, such as soup cans (in a

decidedly framework), dian was t he place of stove

tops and TVs-the "Willowdale worldview"-and wondering how these

things fit into her own life, the lives of women, and the relationships of

power and oppression Whether dian was working with community

organizations or on a personal piece, she often proved to be a scavenger,

"collect ing and connecting seemingly unrelated material, events, ideas,

and occurrences""

IntroduCtion 7

The production and critical reflection included a focus on the

very act of producing art , the nature of individual and collective creation.

Dian would name individual prints from one production differently, and

she would number pri nts mi sleadingly. Inst ead of numbering a set of

prints consecutively from one t o ten, for example, she might give five or

six of them the number one. While she made a choice to stay root ed in

activism and education rather than enter the mainstream art world, she

was clearly part of an emerging practice of art-a

practice that challenges the constructi on of t he arti st as lone producer

and instead locates art inside a constellation of relati onships and

interests and discussions: re:framing what we see as art. She was

interested in demystifying the producti on processes of art and in using

drawing, painting, collaging. photography. and role play

as ways of communicating. ways of learning.

Her art pervaded her life. In t he hospital a few days before she

died. with all three members of her immediate family sitting on the bed.

dian asked if they could see the bird perched on her knee. She qui ckly

noticed the puzzled response. deduced that she was hallucinating. and

then, with a smil e, suggested, 'Sara. get a pen and I'll tell you how to

draw it" The result was a bird much like the one portrayed in her

"Bird on the edge about t o ... "

}( Bird on the edge about to ... (1975)

8 Wild Garden

The art (like the teaching) was often wild and flamboyant , but t hen too

so was dian marino. One day you might see her wearing a ring of silver

hearts on her head. Another day it would be neon pink plastic stars. Dian

wrote her name self-consciously in lower-case letters, not just out of a

sense of arti stic playfulness but more seri ously to foreground questions

of authority and power In 1960 a teacher who hadn't qui te got her intent

noted at the end of an essay, "Your principle of capitalization seems

obscure"

In her work and everyday life she was a champion of resistance,

especially resistance to received notions of "artist" and "educator " She

was consistently concerned wi th relations of power, of all types, and the

resulting need not just for resistance t o power but al so for strategies of

empowerment , of all types; although later on she began to have doubts

about the much-used word "empower. " In "Reveali ng Assumptions, " she

says, "You can't empower people ... I think that is a real consumer use of

the word empower"

As a teacher di an was engrossed in the critical examinati on of

the theories and practice of learning. In her classes she discussed crit ical

education, creat ivity, storytelling, and the theories of Gramsci. As a

critical educat or she combined a number of different methods: lectures,

small group discussions, drama, popul ar education t echniques, and

visual expression, among others. Her st orytelli ng strategy worked to form

meaning out of experience. She resisted the academic understanding of

knowl edge as totally scientific, exact, exacti ng, handed down. For her

students and others the challenge would always be there to rethink

assumptions and reflect on t he notion that each of us is a knowledge

producer; each of us has an important personal voice. "A l ot of what

critical education is about is t aking ourselves seriously as producers of

knowledge," she told students'"

No discussion of dian's work can ignore it s theoreti cal

grounding. She embraced theoretical discourse and loved to develop her

understanding of complex ideas; t o communicate those ideas in ways

tailored to her audience and the moment; and, perhaps most

importantly, to stimulate and encourage their modifi cat ion, adaptation,

and application to current circumstances. Three theoretical notions were

particularly important to her conjunctural meaning, hegemony, and

re:framing.

Introduction

9

10

people in passing' what's heard and no heard

Wal ing down Bloor 5 ree lhis summer, not far from where I live-I

wear th se hea -shaped sun glasses, and you can tell when people

hit your ey The rest of my clothes ar quite au rage-ous, but people

can avoid that. can control themsel , either looking down or off in

another direction.

But wha I found with my heart-shaped glasses IS that the

people will work heir way up, and wh n they gel to th glasses

they'll laugh, or they'll smite. or they'll giggle, or th y'll want to know

wh re I got hem. I 's all just too funny 0 be- taken seriously. I hink

part a wha happens with people and my clothes sometimes is they

get nervous about me. Maybe it's important. You know, that it's a

s dous kind of hing, and When they get to he heart-shaped glasses

they move to ana her level. Somehow or other, h y can't restrain

themselv .. they smil

I deHghts mohave encounters wi h people I don't know,

will never know again, and to have that passing mom n of contact

that is memorable, I rememb r the faces of people (fS hey go

by, as they smile. And I'm sure they remember the momen 00.

One time I was walking along Bloor Street with my husband

Chuck and the kids, just east of Brunswick Avenue. They were ahead

of me and had just crossed the stree to go 0 our car, which was

parked a Ii Ie way down a sid 51r et. I was wal ing along, and this

guy was about fifteen ee away from me. He spreads ou his arms

and yells out, "YOU LOO FANTASTIC!" He was very heatric:al about

it, and I miled bad<, Then he cam ov rome and said. in a voice

that only I could hear-"butabitostenta

H turned around and walked away ... and I'm glowtng with

laugh ert because everyo e nearby hard the very loud Irst part, no

th second. Then, fi een eet behind me now, he said, as loudly as he

could, And make sure you wear the sam thlO9 tomorrow!"

Wild Garden

I th,ink for me humour and playfulness have to be so many layers.

There is an element of th absurd, or paradoxical or contradictory,

tha just makes my playfulness come to the forefront. Uke one time

in an art class an artist was holding forth on abstract painting. He

said something abou an ~ a b s t r a c t priest," and I fell off my chair

laughing. I couldn't contain myself. This very serious talk had gone

too far. "Abstract priest' was 5uch a contradiction, and at the same

time it was accurate. I mean, priests are real people. They aren'

abstract, and they also act right out of it. At one fell swoop this

artist had described about six aspects of a reality.

As an inveterate storyteller dian was always givi ng out accounts

of herself as situated in specifi c "conjunctures," relating stories and

ti mes i n which she had made decisions t hat changed her as an arti st and

educat or. She reflected on the ci rcumstances that shaped her. Wit h

distinct pleasure and pride in her mother' S idi osyncratic ingenuity, she

would t race her own creativi ty back t o her mother'S uni que use of

conventi onal househol d items.

To see meani ngs as "conjunct ural" is to suggest that what are

normally descri bed as "objecti ve truths" are better understood as events

or moments in whi ch we are looking at or experiencing a unique comi ng

together of particul ar forces, of rel ations and their history, and of space-

ti me frames- and that all of these elements can vary according t o how

we adj ust our lens

9

We may want to examine a conjunct ure wi t hin the

frame of a decade, a year, or a day; or withi n a nati on, a ci ty, a

neighbourhood, a famil y, or a backyard

Introduction 11

not quite according to the manufacturer's

instructions

While visiting my childhood home in Milwaukee, I came across

my mother washin ome dishes at the kitchen sink. A not

llnfamiliar sight. I looked around the ki chen and everything Was

idy, in order. Too much order. It se med like something was

amiss.

"Isn't it pickling timer I a ked.

e5, i s that ime of year," my mo her answered.

"Then wher are he gherkins?"

Hln the bas ment."

Oh, of course, t he basem nt. I thought, and headed

downstairs to view the harvest as if aI/ was right and proper.

Half- way down I wond red, "Why on earth would the gherkins be

n the basementr Then, as I looked around e basement the

gh rkins were still not in evid nce. "Where are they?" I shouted

UP he staI rs. "In the washing machine," my mother called back,

qUite nonchalantly and totally unexp ctedly. I wal ed over to the

washer and opened the lid 0 see dozens of baby cucumbers

being rliC Iy tossed around in the watery cycle of the Maytag.

"Not wha he salesmen had in mind," I laughed to

myself. As I returned upstairs, inspired by my mo h r's ingenuity,

J laughed harder and harder as I pictured washing machines the

neighbou hood over- all Illed wi h Ii Ie green gherkins gently

bathing in cool bas ments in lhe hot a emoon.

Dian oft en described the hard work of critical educati on in the

context of social st ruggle, often in coalitions of interest s, as being about

"keeping difficult company" She said, '" always try t o keep some difficul t

company." Another t i me she put this less delicat ely as needing to have

"at least two asshoIes around." And yet another time:

Wild Garden

When I worked at Parti cipatory Research I found we had a lot of

homogenei ty about our values, and i felt if I didn't get myself

into diverse situations I woul d slip into great arrogance I would

start to think the whole world ran like our little bit. and if it

didn't it ought to or we're in deep and serious sh it What I had to

do to keep myself open (I would it humble) i s t o loiter with

other kinds of folks.'O

This need for "diffi cult company" can be seen as both a pragmatic and an

ideali stic vent ure pragmaticall y it recogn that those involved in

emancipatory education have differences that can cause creative

tensions; idealistically, it implies the need to embrace and negotiate

difference in order to evolve collectively The significance of conjunctural

meaning lies in its potential for helping us t o embrace and include bot h

objective and subjective (constructionist. intuitive) ways of knowing.

Donna Haraway, a professor in the History of Consciousness program at

the University of California, Santa Cruz, points, for instance, to the

danger for feminists of narrowing this search, of analysing everything

from the point of vi ew of radical constructi vism.

11

According to Haraway,

a rejection of "obj ectivity" as having any legitimate meaning will almost

certainly exclude the constructivist from t he terrain of scient ific inquiry,

all owi ng patri archal science to proceed without any accountability to

femini st criticism.

"Hegemony" is a cent ral theoretical construct in dian marino's work t hat

names a process of social-pol iti cal control persuasion of the mass of

society by a coalition of ruling-class interests, involving the consent of

the masses themselves (persuasion from above, and consent from

below) As media analyst Todd Gitlin explai ns the concept of hegemony:

"Those who rule t he dominant institutions secure their power in large

measure directly and indirectly, by impressing their definitions of the

situation upon those t hey ruie and, if not usurping the whole of

ideological space, still Significantly limiting what is thought throughout

the society""

What was once achieved by brute force-and still is today in

some s o c i e t i e s ~ i s now more often achieved through the promotion and

In t rod uction 13

14

legitimation of ideologies passed off as "common sense." The mass

media, education systems, entertai nment and publicity industries,

popul ar culture instit utions, and institutional ized religions all playa

major role in conveying ideology as simple, unassail able reality

Hegemony depends in good measure on both the obscuring (or mystifi-

cation) of power relations and the threat of coercion As di an puts it in

"Landscape for an Easily Influenced Mind," which opens this collection:

"[ like the relational aspect of a concept like Ihegemony! as it resonates

with my experience and my art. I al so li ke the flexibility the concept gives

me to move between the individual and the social; it tells me that

consent can be both personal and socia!. "

Another Gramscian term, "counterhegemony," signifies the

oppositional struggl e for a new hegemony. If we see hegemony as a

system t hat organizes consent, we have the choi ce of reorganizing or

disorganizing that consent. If hegemony is a frame, we can chall enge

that frame and work to "re:frame" what ever it is that is caught wi thin our

sights. One of Corita Kent's art-class exercises had a life-long impact on

dian Kent would ask her students to glue Popsicle sticks together in

some sort of frame-square, rectangl e, triangle, or whatever-and t hen

to go outdoors and throw their frames into the air as far as they could.

She asked the students to study what was "framed" wherever the st icks

landed, and to notice how the frame interacted with what was framed,

the "subject " In her thesis "Re:framing: A Critical Interpretation of the

Collective production of Popular Education Materials," dian concludes

that reframing "is most likely to happen when a group i n the process of

producing something concrete (as in popular educational materials)

expresses and confronts the context of current everyday problems."13

A reJraming that disorganizes while reorganizing consent has

the potent ial to be a powerful anti-hegemonic t ool. Dian argues that

consent is never one hundred per cent, that an individual 's or a group's

consent to the hegemonic routine is never compl ete-it is always in

process-being established and re-established daily There are always a

few ledges, a few cracks, in the seemingly "monolithic" wall of consent.

When people work collecti vely, opport unities arise in which

communicati on and negotiation are necessary in order to proceed with

the work at hand. These are opportunities to convey different

experi ences of creativity, co-operation, and leadership. They allow for the

posing of cri tical questions t hat can serve as frames for dialogue and

collective learning. As understandings of different experiences are

Wild Garden

negotiated, opportuni t ies to experience and refl ect on cracks in consent

proliferate. The dialogues that happen in group situations are fil led with

chances to examine, even widen, cracks in consent

In this process of re:framing dian used a pedagogical tool that

she called the "st ructured criticism," which involved a student identifyi ng

two or three connecti ons made in a class-from a reading, an event , or

perhaps the class dynamic itself Students were encouraged to do the

exercise quickly, to use whimsical or personal headlines to title their

thoughts, and to challenge their own thinking

Dian told the following story to new students of the Faculty of

Environmental Studies:

There was once a general of war who was t ired of

fighting. He had spent his whole life perfecting his skill in all the

arts of war, save archery, but now he was weary and wanted to

end his career as a fighter. He decided to spend the rest of his

days studying archery, and he began to search far and wide for a

master who would teach him.

After much j ourneying he found a monastery where they

taught archery, so he went in and asked if he could live there

and study. He stayed ten years, practising and perfecting his skill

as an archer. One day the abbot of the monastery came to him

and told him he had to leave. The general of war protested,

saying t hat his life in t he world outside the monastery was over

and that all he wished was to spend the rest of his days there.

But the abbot insisted, saying the general was now a great

archer and he must leave and go into the world and teach what

he had learned.

The general did as he was told, and having nowhere else

to go he decided to return to the village of his birth. After a long

journey he was finally nearing the village when he noticed a

bull's-eye drawn on a tree, with an arrow dead-centre in the

Introduction

16

target H was surprised by thi , and even more surprised as he

walked on to find other rees wi h bull's-ey drawn on them, with

arrows in the centre of every one. As h kept walking he saw, on

he barns and the buildings of the own, dozens, hundreds, of

bull's-eyes, all with arrows stuck in the cent e.

The peace he had attained in all hears 0 monas it life

and training left him, and he approa hed the Id rs of the town,

indignan that after te years of d voted s udy h should return to

his own home and find an afcher more skilled than he was. H

demanded hat the elders g t this master archer 0 meet him by an

old mill at the edge 0 town in one hour.

WaJ lng by the mill, the gen ral saw no one coming to

mee hfm, hough he noticed a young girl plaYIng by the river.

Ev ntually he girl came over, looked up at him, and asked, -Are you

wai ing for someone)"

"Go away," he said,

"No, no," said the girl, you look like you're wat ing for

someone, and I was tol d a come and n eet someone her .

The general looked unbelievingly at the little girl and sold,

"I'm waiting for the ma ter archer re ponsible or he hundreds of

perfect shots I see around h re."

"That' me," aid the girl.

The general, even mo sceptical now, said, "If you're

telling the truth, explaIn to me. how you can get a perfect sho

every single' tim you shoot our arrow."

" T h a t ' ~ easy," said the girl "I take my arrow and I draw I

ba k in the bow and pOint j' ve'ry, very waigh Then' let i go and

whf:rever it lands I draw a buJl' -eye. ~

Wild Garden

A folk-t al e like the story of

the general and bull's-eyes, a story

that dian would tell her students

at the beginning of a course,

would become a way of disarming

listeners, dealing wi th the

inevitable nervousness of

beginning and communicating a

sense of care and fun This is a

radica lly subjective story to

introduce to new students coming

into the uni versity to be

"instructed." The truly radical

teaching here is communicated

metaphorically define your own

frame. The story enlarges one of the

"cracks" in dian's consent: as an

academic authority she is

authorizing students to define

their own terms, and she is doing

this not in a didactic way but in

the form of a narrative that allows

for mUltiple interpretati ons. For

dian there are always contra-

dictions and disruptions (a

favourite word)-and the "contra-

dictions" and "di srupti ve

participation" aren't just in the

capitalist mainstream of

controlling institutions, but in her

own work, thought, feelings There

International Conference on Participatory Research,

Venezuela, 1979, with Budd Hall

are al ways "mul tiple answers to problems," t here is always

'unexpected." The term "creative misinterpretation" is hers; according to

friends and colleagues Leesa Fawcett and Ray Rogers, "She used it to

describe the way someone would !deliberately or otherwise I misinterpret

a question or piece of information so as to respond in such a way that

created a different perspective on 'what we already know' and shed new

light on it. "''

Introduction

~ ! !

' v ~ '

~ -

.:f f

17

18

Through this pract ice of re:framing, learning becomes not simply

a cognitive but also an emotional undertaking. As one of her students

put it, "The entire class would be howling wi th laught er, and then we

would stop and we'd realize-hey!- l've never thought about that

before."ls

"Always be passionately aware that you could be completely wrong." This

sobering aphorism acts as an excellent gatekeeper to the portals of

critical thought. Dian mari no taught many of us t o open ourselves to

unasked for and unpredict able learni ngs.

Indeed, the articles and art collected here show t hat dian hersel f

was ever changi ng, shifting in her positions and point of view. She was

.always exploring where she had gone in her classrooms and in her

relations with people. looking at what had gone right and, just as often,

what had gone wrong or, more importantly, gone missing-what had

been silenced-what were the limitations of her methodology or

approach.

Linda Briskin, a friend and c o ~ w o r k e r at York University,

remarked on how dian shared her craft with people around her, the way

"she went boldl y to the truth of t hings when many of us hesit ated ... the

way she surrounded herself with colour and light, hearts and stars,

invigorating every room she was in. dian's joy, her sense of the possible,

and her outrageousness inspired new ways of seeing and being with the

ordinary." 16

Had she lived there i s no way of telli ng where she would have

been now, in the closing years of the 1 990s, or what she would have

thought about the content of these articles or the reproducti on of her

art. But we are certain that she would have gone on deconstructing,

reconstructing, taking risks, "embracing the mess"-Iearning by mistakes,

affirming mistakes, and bounci ng wild and wonderful ideas around in a

constant effort to subvert authori ty and shift the location of power and

what she calls "the chunks of lived process."

Wild Garden

EI'4

1. Landscape for an I

EaSi ly Influenced MindV

Reflec ti ons on My Experience as

an Artist and Educ ator /

M

ine is not an unrelenting story of resistance. I see myself as very

much embedded in my community, with all the complexities that

accompany a sense of place. The story of my education is like other

stories, very untidy, cluttered with moments clarity and simplicity as

19

well as with curiously unfinished or incomplet e thought s. There is a

wildness in me and the world I am part of. which I have to respect, and

at the same time I know I have undergone a process of soci al

construction as an artist and educator

My personal-and selective-history is not, then, a dichot omous

development but rather a rain forest of moveable relations. It is closer t o

a Gabriel Garcia Marquez novel than a ministry of education report . In

any case, I like to think that at least some of the materials I've produced

as "artist" over the years illustrate this proposition: that critical thinking

and production can have creativity as an intimate constituent. These

tools help to explain some of the questi ons/confusions from my past

experiences and have also enhanced my practice as an art ist and teacher.

Some of the tools-like the term hegemony--can seem heavy, perhaps,

but 1 like the relational aspect of a concept like that as it resonates wit h

my experience and my art. I also like the flexibility the concept gives me

to move between the individual and the social; it tells me t hat consent

can be both personal and social.

he g e:rn 0 n y Writer Phil ip Slater tells a story:

Wf

20

Once there was a man who lost his legs and was bli nded in an accident. To

compensate for his losses, he developed great strength and agilit y in his hands

and arms, and great acuity in hearing. He composed magnificent music and

performed amazing feats. Others were so impressed with his achievements

that they had tflemselves bli nded and their legs amputated I

This parable shocks us. "Certainly none of us would be so stupid as to

blind or maim ourselves, " we respond. Yet, frequently, to interpret our

experience we have been persuaded t o use categories (names) that are

or distracting. When I was thirty I was still using the

category "girl " t o organize how I thought about myself No one had to

come and point a gun at my head and say, "dian, don't take yourself

seriously" The attitude came with the name (category) that I was using

to think about myself. Where did! learn to interpret myself in this less

than empowering way? All those everyday spots-the family, school,

media, work, even play-persuaded me to see the world from someone

else's point of view, without questioning how it might work differently for

me.

Wild Garden

This sort of persuasion is not always i ntenti onal. The peopl e in

power are socialized too, and I think it is not so useful to think of

persuasion only in a conspiratorial framework

2

IGramsci 'sj concept of hegemony embodied a hypothesis that

wi thin a social order, there must be a substratum of

agreement so powerful that it can counteract the division and

disruptive forces arising from conflicting interests .. The masses,

Gramsci seems to be saying, are confi ned withi n the boundaries

of the dominant worldview, a divergent, loosely adjusted

patchwork of ideas and outlooks, which despite heterogeneity,

unambiguously serves the interest of the powerful. by mystifying

power relations. by justifying various forms of sacrifi ce and

deprivation, by inducing fatalism and passivity, and by narrowing

mental horizons .... The reigning ideology molds desires, values

and expectati ons in a way that st abilizes an inegalitarian

system.'

wild gardens

Environment is really important. I have to look at organic matter in

order 0 be creative. I find built environmen interesting and

oppressive. Because I use' everything that is within two and a half

feet of me I have to take care that everything within two and a half

feet of me is beautiful.

I'll grant you that my de mition of wild g-ardens may not be

everyone's definition of Some people take tranquillizers to

survive. I need a wild garden. If I cannot see or go among trees and

plants I feel myself shrivelling up. I absolu ely need that kind of wild

beauty, j nurtures m .

I also need at least "'10 assholes around. I I'm only around

people I love, I search out asshol . I wan people to challenge me.

Landscape for an Influenced Mind 21

W,

22

Consent-the other side of persuasion- is complicat ed and

never comes without some resistance. When we consent to something

we take on a position that is not necessari ly in our best interests. The

languages of resistance are the ways in which we reveal to ourselves and

others that we are questioning the story I use the phrase "cracks in

consent" to construct from our personal narrat ives a hi story of resist ance

and even transformation. This shift to a more explicitly political

orientati on can lead to empowerment, but it is not easy or automat ic

There are also lots of examples of incomplete or sabotaged resistance.

Collective silk-screen with YWCA Committee on Violence

Against Women Internationally (1984)

V,/ild Garden

hands on

Identifying Cracks in Consent

Use this tool when you want to clarify how we might be unintentionally

reproducing hegemonic patterns in our own lives and work, and to

consi der how we might develop alternatives.

Everyone has a history of resistance, but we might not remember this history as

being about resistance because it is often coded in the language of the persuader.

The resistance might have been seen, for instance, as bad behaviour, inappropriate

actions, wrong attitudes, breaking the rules, or something calling for punishment.

These histories of resistance have an impact on our efforts to develop a sense of

control over our learning.

This tool is meant as a way for us to recover and become sensitive to the

various voices of hegemony in our day-to-day lives. I've divided these voices into

four groups:

a) phrases of persuasion. These are expressions used by people in power to persuade

us that it is in our best interests to support their practices and polici es. For

instance, "We have no other choices, it's inevitable," or "The tide of t echnology

and economics can't be reversed," or "The marketplace has to decide."

b) phrases of consent. When we try to make sense of our difficulties of making ends

meet, we can sometimes hear ourselves uttering consent phrases: '" can't seem to

get ahead, but we're all more or less in the same boat, so what can you do?" or

"This is a very complex problem, so let the experts [those in power] figure it out,"

or "It's just the way things are."

c) phrases of resi stance. There are times when we actively resist or say no to

something: "No to lead poisoning," or "No to the de-indexing of pensions," or "No

to more hospital cutbacks," or "No to nuclear weapons."

d) phrases of transformati on. These tend to describe a sense of well-being or of

power to change something, not just individually but structurally or socially. Such

phrases need to be used to celebrate and remember a particular moment or

situation from the point of view of those who now feel more empowered. In a

Landscape for Influenced Mind 23

24

hands on

language of persuasion, people take individual blame for problems; in a language

of transformati on they begin to look at the systemic relat ions that create and

maintain the problems.

The phrases can often represent small and scarcely noticeable shifts. For

example, a group of people who were evaluating a project obj ected to the

heading "What we did wrong" and changed it t o "What we could do better,"

which they felt both affirmed thei r efforts and allowed them to be tough-minded

critics at the same time.

Or the phrases might represent a more dramatic shift in approach to a

problem. Someone in a factory, for instance, might be heard saying, "That

machine almost took my hand off. I should have known better-everyone knows

that you have to be careful on that machine." But a phrase of transformation

would be something like: "The company has known about the problems with that

machine for ages. They should do something about it-or we/ve got to get them to

do something about it."

What we want to do is

1. Identify key phrases that are a part of ei ther the persuasi on or consent aspect of

hegemony.

2. Recover our own histories of resi stance.

3. Identify how we might express our resistance and identify possible means of

transformation.

Here's how t o do it

1. Ask participants to break into groups based on their everyday work situations.

2. Then ask each person in the group to say four or five sentences about key charac-

teristics of their work situations.

3. Ask participants to brainstorm phrases of persuasion-phrases used by peopl e in

positions of power-that have pressured them to do something that from past

experience or through reflection they can now see was not in their best interests.

These phrases of persuasion can come from a wide range of voices: from

politicians-local, national, or international-to workplace "managers" or the

mainstream media.

Wild Garden

hands on

4. Ask participants to brainstorm phrases of consent-expressions they've used

themselves, or that they've heard others saying- t hat tend to push them or the

others to agree to do something that may not be in their best interests.

5. Next, brainstorm a list of phrases of resistance-words that participants remember

saying themselves at certain times, or that they've witnessed in their own lives.

6. Ask participants to generate a list of phrases of transformation-things they say

when they feel that some significant change has taken place.

7. Report back: the phrases that the group comes up with in the various steps can

be reported back in a plenary session. Or they can be used as raw material for

producing a group mural or a soci o- drama, or used in some other creative way to

carry the learnings experienced in the small group out to the large group.

Languages of transformation are often compl icated. because they

propose an alternative and try not to reproduce relations of power over

people or places or ot her species. This is somet imes referred to as

counternegemony, but I find that often we use parall el constructions so that

too frequently counterhegemony comes to mean persuading and

obtaining a different consent and thus reproducing relations of

domination and subordination. The language of consent can dull our

imaginations in one sense, in that we become so used to thinking about

teaching, for example, as in "J am persuading and I have a position and

am not obiective"- and feel that we are therefore imposing ourselves-

or we hide our position and present an "objective account"-thus trying

not to impose our position. The notion that we can communicate and

articulate our positions, engaging with people but not overpowering

them, seems uni magi nable

from consent

to disruption

When we consent we use phrases that support the language of

persuasion. We police ourselves by continually repeating ideas like "This

is too complex," or "I'm not an expert." or "It's just the way things are and

who am I to tell the president he's naked?" We learn these phrases

throughout our life-long education. The persuasion of the dominant

powers establishes a powerful socializing of our imaginations that leads

us too often to making choices contrary to our own interests.

Landscape for an Influenced Mind

25

26

Recently I visited my parents' home, and many of the drawings

and paintings that I had made during high school were up on the wall s.

was struck by their stat ic quali ties. They were often of obj ects and about

objects rather than relationships For me this was an example of my

consenting to a passive interpretation of my subjectivity as well as of my

role in representing the subjectivi t y of the world. StilL the works were

about whatever was right under my nose The subject-matter was seldom

the exotic but usually an exploration of an everyday thing. I think there

are cracks in our consent, and we resist where we can.

There seem to be acts of resist ance throughout our individual

and social histories. Many of these actions of resistance, while

courageous and creative, appear to be appropriated by the mainstream.

We can all probably remember moments in our own personal histories

where we said, "No, that's not fair," or "No, you' re not doing what you

said you would." We stand up to authority, whether it is at home, schooL

with an employer, or in the community, and yet gradually we come to

understand that our clarity and wisdom are used to rationali ze the

benevolence and tolerance of liberalism. We are reduced to being

i ndi vi duals, and many different methods are used to isolate and manage

our acts so that we can sometimes be left with the feeling t hat we are

not "team players" or that we are "THE PROBLEM." There is another ki nd

of resistance, which is more social, and yet too frequently this resistance

ends up imprisoning us, not emancipating us in any long-term or

significant way. Paul Willis documents this kind of resistance in his book

about rebell ious working-class "l ads" who had a kind of organized

resistance but st ill ended up, in their own way, in maintaining existing

relations of domination and subordination, both at the macro level and

with t heir families:

Looking for the aesthetic in the everyday, in the ordi nary, is a

small gesture of advocacy. We hardly ever consent one hundred per cent

to our own invisibility, to our own subordination. Watching television, we

can all laugh at how dumb some commercial s are. Al most every day we

make critical observations or interpretations, yet somehow, until we

breach the silence and send out an active "no!" we are not able to

organize that resi stance, or take it seriously.

I now understand an incident from a high-school art class as one

of those disempowering engagements. The art teacher told me I was

"speCi al " and should work in a room by myself so I wouldn't intimidate

the rest of the class. The problem from the teacher's point of view was

Wild Garden

-

that I tended to only listen to part of her directions for the assignment s.

When I was asked t o produce one mosaic, I'd make ten. Not all of these

producti ons worked, but some of them turned out fine-original yet

connective. My peers tended to foll ow the instructi ons more carefully,

oft en sabotaging t heir own creativi ty in the process They recei ved B's

and C's, while I got !\s. But then after we were placed in separate rooms

we lost our opportuni ty to compare and talk about the work and marks.

So I was persuaded of and consented to the interpretation that as an

"artist" I was special, different. privileged, and that [ could intimidate my

peers and should stay away from t hem. I didn't wholly bel ieve this, and [

would sneak back in whenever possible and visit with them, though not

with any seri ous intentions; it was more an act of resist ing t he isolation.

! can only now imagine how disruptive it woul d have been t o

start discussing who got what grades whi le we were making mosaics-

and then to begin analysing procedures and the detai ls of where these

different marks might have come from. ! now know that creati vity is

greatly enhanced by the act of produci ng many versions of what would

ot herwise seem to be the same thing, and that the process of making art

is not such a magical or exceptional pattern it can be learned. But the

myth of artistic creat ivity haunted me t hroughout my educati on as an

arti st and was one of the most diffi cul t t o resi st and t ransform when I

wanted to work as an art ist withi n soci al st ruggles

These reflections suggest that there were procedures and

practices t hat domesti cated me as an arti st. But [ al so think there was a

wildness that came from my intuitive self and a curi ous and j ustice-

ori ented part of me that wanted hurt and pai n to be heal ed and not

denied When the concept ion of change is beyond the limits of the

possibl e, t here are no words t o art iculate di scontent, so it is sometimes

held not to exist. This mi staken belief arises because we can on ly grasp

sil ence in the moment in which it is breaking. The sound of breaking

silence makes us understand what we could not hear before. But t he fact

that we could not hear doesn't prove that no pain existed.'

Landscape for an Easily Influenced Mind 27

Jenny's gone fishing (1980)

8 . White Flowers and a

Gri Z l y Bear

Li ving w ith Can cer

W

hen I woke up in the recovery room in November 1978, my

doctor was waiting to tell me the results of the biopsy. It

couldn't happen to me; I was just thirty-seven years old. But it had-l

had breast cancer. My feelings ricocheted all over the place. I was afraid,

angry, grateful, and sad all at the same ti me. I remember thinking: 'Tve

145

146

been a caring person, how coul d thi s happen to me? It's not fair, it's so

arbitrary " I cried, wailed, and curled up into a ball, but I also continued

to work-it seemed like my sanity depended on returning to "normal" as

quickly as possible. A month of radiation treatment s began a long series

of checkups, more biopsies, and finally surgeries My last surgery was i n

1983-a lymphectomy; afterwards I was put on a hormone blocker. Last

summer, the summer of 1988, I was nearing the famous "five-year"

marker. which meant that statistically I had a much better chance of

surviving. Then I had a bone-scan and they discovered bone cancer in

two pl aces. I was put on another hormone blocker and given more

radiation. I had the summer to put my life into a new framework: "The

best we can do is slow it down," they said.

Writing this is difficult. It brings up complex and contradictory memories.

But it does add both a clarity and simplicity that wasn't there at the

time. Perhaps this article should be written by

my husband and daughters, who know what

happens when someone you love gets cancer.

Or by my friends, who've shared my fears,

anger, frustrati on. and even the small

moments of beauty that have come from

trying t o make sense of cancer.

I have resisted putting words on paper

for fear of getti ng back on an emot ional roller

coaster. Also because what has helped me to

understand and live more calmly with cancer

may not work as a "prescription" for others.

The sense of loss of control is so great with

this illness, that it is a time to be very careful

about issues of power and controL While

waiting i n clinics and hospital corri dors I have

found that many people are not as

enthusiastic as me about getting knowledge about their illnesses and for

playing an active role in their health care. Deat h is such a responsibility

that I hesitate to project my keenness to be clearer, to understand better.

onto others who share my illness. I write not to prescribe but to describe

and wonder aloud about some difficult times.

Wild Garden

For me there is irony in the act of reflecting on cancer, because

I'm the kind of person who might easily have left these thoughts until

five minutes before death. I too frequently gallop into new projects

without sufficient time for contemplati on But in trying to make sense of

cancer I think it is important to speak out in a straightforward manner.

The knowledgegained from coming to terms with this disease too easily

remains in the hands of medical professionals So I stumble for words to

speak of problems, responses, speculation, small rearrangements

As a visual artist and teacher I use many kinds of language For me the

meaning of words changes with time and place. How we use words

indicates our val ues and priorities. I have found most writing about

cancer disempowers those of us who have the disease. One example is

the use of militaristic or war-like metaphors Words and phrases like

"fight," "beat." and "win the war" are commonplace But if I get into a

"war" with my cancer, I can only interpret myself winning if my cancer

"loses" or is "defeated. " This of ei ther/or thi nking reduces all

experience to winning or losing. A person like myself wi th a "terminal"

cancer has automatically lost.

We do need a language of resistance in our struggles with

chronic illness, but it needs to a language free of militarism. I found it

wonderfully heal ing to spend quiet time in nature-a form of resistance

perhaps, but hardly a battle Even supposedly alternative language can

be infuriating. The "new age" philosophy of illness is a good example. At

first. I would go out and buy t he latest sel f-help books. only to fi nd the

basic message was "You made yourself sick. so you can heal yourself" So

simple but so damaging. It fits ail too well with mass media messages

that bombard us daily: problems are individual. not social. We're kept

disorganized with a Simplistic presentati on of blame and responsibility.

I began to think about how I got cancer. I read and asked around.

There were many possible explanations-heredity (my grandmother died

very young from breast cancer), occupational hazards (for the previous

twenty years I had made silk-screen prints using highly toxic paints and

clean-up solutions). poor diet, lack of exerci se, too much stress, birth-

control pills. and many more. Often I read that one or another of these

factors was the primary cause. I found this completely immobilizing, so

gradually I developed a map, a kind of ecology of possible causes. This

White Flowers and a Grizzly Bear

...

~ f ~ : ; ~ ~ .

147

allowed me to deal wi th those dimensions that I had some control over. I

didn't feel like I needed to have a "scient ific map," but could elaborate

my own open map so that as my experience grew I could alter it.

By the t ime cancer was diagnosed I had an excellent relationship

with my doctor. He trusted me as an expert on my aches, pains, and

feelings; I trusted him because he was able to tell me what he didn't

know as well as what he did. He also knew how to cry. Most doctors see

surgery as a response to unhealth, he told me. So advice from a surgeon

must be seen from this critical vantage point. He was open to my

exploring alternat ive health supports (li ke massage therapy) and would

ask me whether they were having any effect. It was important to me to

understand the limits of medical knowledge and to recognize the

intuitive as a legitimate part of making decisions.

In the first five years I had four surgeries. Whenever I asked the

experts about the odds of survival for different cancers, at first they

would answer ambiguousl y. When I persisted they would get more

precise. Later I learned this was ca ll ed "stagi ng," a way of finding out

what patients really want to know. Some doctors withhold information

based on whether or not they think you can handle it. I would say you

should lose those characters fast. If they can't trust you, how can you

ever t rust t hem?

I need to know as much as possible so I can get the most out of

the time I have left. It doesn't mean that I wasn' t overwhelmed and

angui shed when I heard cancer had returned. But knowledge and

understanding helped liberate me from fear, anger, and

sadness. These feelings are always close by. But now I have learned to

treat them as reminders of my current agenda- to figure my way as

creatively and peacefull y as possi ble through the last part of my life.

Wild Garden

epitaph

You had to writ hos hmgs In high school-wha do you want -saId

about you-what do you call it? That speech at the end: EPITAPH. I said

I would lik it to be known tha I wen hrough the world and caus d

eopl to be happier, to laugh more. At tI e tim I considered myself a

Mr. Blue. So I thought that was a gr at goal in lif

I was he aides in my family, my sister was eigh een months

younger than I was. and one of my cons ant recollections of being a kid

was my younger SIS er telling me to grow up and stop laughing. I saw

hings as quite funny for a long ime.

Through he middle part of my life, especially during the

seventies, I f It mar obligated, more pressure, as a woman I guess, to

be more discreet about seeing hings as fu ny all the time. I felt

White Flowers and Grizzly Bear

149

I

: !

" I

I

: ;

i

I

ISO

perhaps I was laughmg and enJoYing myself too much. Maybe I had a

fear of su 55- maybe that's why I would tend to laugh instead of

being serious. Bu at hat Ime my sense was that to ge ahead-and I

am very compe it ive, a high- need achiever- weJl, I thought. maybe "m

avoiding some hing by laughing. It was also a very humanistic,

Introspective period when a lot of my frIends were trying to get rid of

their blocks. I kept holding out for keeping a few. I said, you know,

something tha '5 been a(ound for 0 long seems like you should keep

wo of hem. j ust in case, kind of like Noah's ark. And I was really

nervous about divesting myself of all kinds of blocks in those little T-

group sessions.

I use my humour 0 undermin authority, I remember a gestalt

war hop where I couldn't believe the contradictions about everyone

being free and open and equal, and the leader was obscuring the fact

tha he was totally in control of he group-he got to name" everything

that was going on, like projections, contact, unfinished business, and so

on. $0 I went after him. playfully. At the midpoint of a morning session

he calfed for a break and told people they could do whatever they

wan ed for h n t half hour. One woman went over to a corner of the

room and stood on her head. The leader remarked, "That's called

showing off." I shoLlt d out, "That's called interpretation." I was trying 0

tell him that despite wna he was teaching he was always one up on the

re of us. I would hay been comfortable if he had own d up 0 tha

but he wouldn't, He r lIy wan ed to keep i as if we wer all equal.

Wild Garden

r

192

connect are far better than never responding for fear of doing "the wrong

thing" A few people told me about their friends' ills (back pains, for

example) as a way of connecting, As much as I appreciated their concern,

I always to say, "Hey, wait a minute, this disease is life-