Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

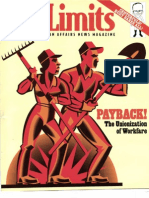

City Limits Magazine, June/July 1996 Issue

Caricato da

City Limits (New York)0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

192 visualizzazioni40 pagineCover Stories: Rage in the Cage, the psychological damage caused by solitary confinement increases inmates' violent tendencies by Sasha Abramsky and Andrew White; Paroled, one inmate's journey back to the streets by Amanda Bower.

Other stories include Kierna Mayo Dawsey on Giuliani's cuts to services for low and moderate income New Yorkers; Isabelle de Pommereau on the Fourth World Movement's dedication to serving the poor of East New York; Steve Mitra on useful government information on the Internet; Seema Nayyar on parents and foster children calling for change in the child welfare bureaucracy; Kemba Johnson on pollution in Hunts Point hurting the health of residents; Dylan Foley and Glenn Thrush on the death of photographer and needle exchange activist Brian Weil; James Bradley on the replacement of manufacturing with gentrification in the city; Jon Kest on Giuliani's announcement of reorganizing the city's school system by following the lead of recent reforms in Chicago; Norman Adler's book review of "They Only Look Dead," by E.J. Dionne Jr.; Camilo Jose Vergara on the Four Corners intersection in Newark and the unacknowledged history of the area.

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCover Stories: Rage in the Cage, the psychological damage caused by solitary confinement increases inmates' violent tendencies by Sasha Abramsky and Andrew White; Paroled, one inmate's journey back to the streets by Amanda Bower.

Other stories include Kierna Mayo Dawsey on Giuliani's cuts to services for low and moderate income New Yorkers; Isabelle de Pommereau on the Fourth World Movement's dedication to serving the poor of East New York; Steve Mitra on useful government information on the Internet; Seema Nayyar on parents and foster children calling for change in the child welfare bureaucracy; Kemba Johnson on pollution in Hunts Point hurting the health of residents; Dylan Foley and Glenn Thrush on the death of photographer and needle exchange activist Brian Weil; James Bradley on the replacement of manufacturing with gentrification in the city; Jon Kest on Giuliani's announcement of reorganizing the city's school system by following the lead of recent reforms in Chicago; Norman Adler's book review of "They Only Look Dead," by E.J. Dionne Jr.; Camilo Jose Vergara on the Four Corners intersection in Newark and the unacknowledged history of the area.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

192 visualizzazioni40 pagineCity Limits Magazine, June/July 1996 Issue

Caricato da

City Limits (New York)Cover Stories: Rage in the Cage, the psychological damage caused by solitary confinement increases inmates' violent tendencies by Sasha Abramsky and Andrew White; Paroled, one inmate's journey back to the streets by Amanda Bower.

Other stories include Kierna Mayo Dawsey on Giuliani's cuts to services for low and moderate income New Yorkers; Isabelle de Pommereau on the Fourth World Movement's dedication to serving the poor of East New York; Steve Mitra on useful government information on the Internet; Seema Nayyar on parents and foster children calling for change in the child welfare bureaucracy; Kemba Johnson on pollution in Hunts Point hurting the health of residents; Dylan Foley and Glenn Thrush on the death of photographer and needle exchange activist Brian Weil; James Bradley on the replacement of manufacturing with gentrification in the city; Jon Kest on Giuliani's announcement of reorganizing the city's school system by following the lead of recent reforms in Chicago; Norman Adler's book review of "They Only Look Dead," by E.J. Dionne Jr.; Camilo Jose Vergara on the Four Corners intersection in Newark and the unacknowledged history of the area.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 40

_'

JUN[/JULY 1996 $3.0 (

Solitary

Psychosis

Kids in

the Cage

A Parolee's

O dyssey

T W ( M T I ( T H A M M I V ( R S A R Y Y ( A R 1 9 1 6 - 1 9 9 6

Unchained

G

ood news arrived from Albany last month when the state

Senate Republicans decided to align with assembly

Democrats in support of a budget that pushes aside

Governor George Pataki's most extreme proposals. Among the policy

ideas at least temporarily left behind: the governor's plans for yet

another massive expansion of the state prison system, lengthy new sen-

tences for several different types of felonies and-most shortsighted and

political of all of the governor's ideas this year-the transfer of 16-year-

old juvenile offenders from teen residential facilities to adult prisons.

Perhaps it's politically acceptable to train impressionable kids how

to be especially violent. But criminal justice experts already know that

treating teenage criminals as adults increases the

...... ,.. .. ~ .... -.-: ... ".. - chances they will commit more crimes when they get

older and makes it more likely they will end up in prison

EDITORIAL

again when they become adults themselves.

This is only one way state governments across the

country exacerbate urban crime problems. Our special

report on prisons in this issue looks at the rapid increase

in the use of solitGlY confinement and the psychological damage it can

cause inmates who ultimately return to our neighborhoods. We look at

the reduction in funding for rehabilitation programs. And for a better

understanding of the tens of thousands of ex-offenders who live in the

city, we profile one man's struggle to break free of his criminal past after

six years inside.

The lesson here is not that New York should have more sympathy for

criminals. It's about comprehending the consequences of locking people

up, agreeing honestly on what it takes to rehabilitate people, and decid-

ing what we should expect from the state before it releases prisoners

back into our communities. Prison is only a temporGlY solution for

crime, and our corrections empire is already an extraordinary drain on

taxes. The New York State system has tripled in size since 1983.

As one top parole official told City Limits, "These guys come back

to the street worse than they were when they went in."

***

A memorial service for I. Donald Terner, the founding executive

director of the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board, will be held June

19 from 1 :00 to 2 :30 pm at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine,

Amsterdam Avenue at West l12th Street. For information on the service

or on how to make donations in Don's memory, call (212) 226-4119.

Cover illustration by Kenneth M. Blumberg

(ity Limits

Volume XXI Number 6

City Limits is published ten times per year, monthly except

bi-monthly issues in June/July and August/September, by

the City Limits Community Information Service, Inc., a non-

profit organization devoted to disseminating information

concerning neighborhood revitalization.

Editor: Andrew White

Senior Editors: Kim Nauer, Glenn Thrush

Special Projects Editor: Kierna Mayo Dawsey

Contributing Editors: James Bradley, Linda Ocasio,

Rob Polner, Robin Epstein

Desi gn Directi on: James Conrad, Paul V. Leone

Advertising Representative: Faith Wiggins

Proofreader: Sandy Socolar

Photographers: Ana Asian, Eric R. Wolf

Intern: Kemba Johnson

Sponsors:

Association for Neighborhood and

Housing Development, Inc.

Pran Institute Center for Community

and Environmental Development

Urban Homesteading Assistance Board

Board of Directors":

Eddie Bautista, New York Lawyers for

the Public Interest

Beverly Cheuvront, City Harvest

Francine Justa, Neighborhood Housing Services

Errol Louis, Central Brooklyn Partnership

Rima McCoy, Action for Community Empowerment

Rebecca Reich, Low Income Housing Fund

Andrew Reicher, UHAB

Tom Robbins, Journalist

Jay Small, ANHD

Doug Turetsky, former City Limits Editor

Pete Williams, National Urban League

"Affiliations for identification only.

Subscription rates are: for individuals and community

groups, $25/0ne Year, $35/Two Years; for businesses,

foundations, banks, government agencies and libraries,

$35/0ne Year, $50/Two Years. Low income, unemployed,

$10/0ne Year.

City Limits welcomes comments and article contributions.

Please include a stamped, self-addressed envelope for

return manuscripts. Material in City Limits does not neces-

sarily reflect the opinion of the sponsoring organizations.

Send correspondence to: City Limits, 40 Prince St., New

York, NY 10012. Postmaster: Send address changes to City

Limits, 40 Prince St., NYC 10012.

Second class postage paid

New York, NY 10001

City Limits IISSN 0199-03301

12121925-9820

FAX 12121966-3407

e-maiILCitLim@aol.com

Copyright 1996. All Rights Reserved. No

portion or portions of this journal may be reprinted with

out the express permission of the publishers.

City Limits is indexed in the Alternative Press

Index and the Avery Index to Architectural

Periodicals and is available on microfilm from University

Microfilms International. Ann Arbor. MI 48106 .

g

CITY LIMITS

JUNE/ JULY 1996

FEATURES

Rage in the Cage

Solitary confinement may sound like a good way to deal with hardened prisoners

-until they're released and hit the streets. When inmates come out of "the hole"

and return home with psychological damage, it's the people around them who

get punished. By Sasha Abramsky and Andrew White

Paroled

An ex-bus driver, shipped home from state prison, fInds no easy way in the

free world. Staying off crack and out of jail is tough. Figuring out what to do with

his life is tougher. By Amanda Bower

Double Exposure

Brian Weirs AIDS photographs and his angry advocacy for needle exchange won him more

than his share of acolytes and enemies. But in the end, the man who strove to inhabit other

people's lives died alone of a heroin overdose. By DylJJn Foley and Glenn Thrush

PROFILE

Worldly Ambitions

France's Fourth World Movement is taking lessons on poverty in East New York.

By Isabelle de Pommereau

PIPELINES

Harmony Rising

Everyone's talking about reforming child welfare, but the voices of parents and children

caught in the system have only just begun to be heard. By Seema Nayyar

Air Assault

Asthma, colds, bronchitis, nosebleeds-what's in the air? Hunts Point residents

yearn to breathe free. By Kemba Johnson

@CTIVISM

Web Research Central

Nine ways to frnd the answer, on-line. By Steve Mitra

COMMENTARY

The Press 131

Industrial Noise By James Bradley

Cityview 132

Chicago Hope By Jon Kest

Review 133

The Ungrateful Dead By Norman Adler

Spare Change 138

Four Comers

By Camilo Jose Vergara

DEPARTMEMTS

Briefs

6, 7 Editorial

Public Housing Stealth Attack

Wisdom in Action

Budget Menu: Rudy's Cold Cuts

Letters

Professional

Directory

Job Ads

2

4

36,37

37

M

Sorry, Sal

We have enormous respect and affec-

tion for Msgr. John Powis, whose inter-

view ["Father of the People"] appeared in

the April issue. It is hard to think of a more

persistent and effective community advo-

cate over the last 30 years.

At the same time, we believe Msgr.

Powis made several statements

Smok. In Your Artlel.

.. _ .. _ - - ~ - " . , . " ... - that require correction. The whole

Industrial Areas Foundation

(IAF) network has no intention of

breaking our 20-year tradition of

Aside from the virtue of revealing how

a motivated group of citizens can affect a

vote of the City Council, your interview

with John Powis does little to enlighten

readers about the real issues of whether the

fire boxes should be removed or not. I

believe you have the responsibility to pro-

vide both sides of an issue, including state-

ments from the politicians your subject

criticizes.

Norman Kaufman

Upper East Side

~ .

L E T T E R S

political nonpartisanship by

endorsing a candidate in the

upcoming mayoral election. We

do not plan to "rally around" any

candidates for public office, as Msgr.

Powis implied. We do intend to register,

train and mobilize thousands of additional

New Yorkers in the election cycle begin-

ning in 1996 and ending in 1998.

Mike Gecan, Rev. Bob Crabb

and eight co-signers

Metro IAF

Colorblind Rud.nus

As a white male professional who has

always dressed in a suit and is usually

carrying a briefcase, I must take excep-

tion to [black parent] Anthony Morton's

feelings that his rude reception in a local

school was based on racism ["Race

Factor," May 1996]. It may have been

racism, but I have received the same

treatment in the same district, in other

city schools--even in affluent New

How Do You TEACH A CLASS

OF SIX BILLION STUDENTS?

These times demand a teacher with inspiring credentials:

the wisdom of a Buddha, the love of the Christ,

the joy of Krishna, the power of the Messiah and

the justice of the Imam Mahdi.

Humanity needs a teacher who embodies all these qualities,

to teach US how to share and live together in peace.

According to international author Benjamin Creme,

this World Teacher is now among us.

"The audience was fascinated. Mr. Creme is exceptional."

AI Angeloro. WNBC, New York

ONE DAY ONLY!

BENJAMIN CREME WILL SPEAK ON

THE EMERGENCE OF MAITREYA, THE WORLD TEACHER

THURSDAY, JULY 11,1996 AT 7:30 PM

SKYTOP ROOM, HOTEL PENNSYLVANIA, 7TH AVE/33RD ST, NYC

A HEALING BLESSING FOLLOWS THE LECTURE.

FREE RECORDED MESSAGE: 212-459-4022

WORLD WIDE WEB: http://www.shareintl.org/

MNN-TV: TUESDAYS AT 10PM ON CHANNEL 69 THRU JUNE

FOR LECTURE INFO, PLEASE CAlL 718-852-8679 OR 718-884-2287. ResERV. NOT NEe. No CHARGE, BUT DONATIONS APPRECIATED.

F

Jersey communities. It does not matter if

you are black or white: all school staff

must have been taught rudeness is a

weapon they can use to keep out all

potential troublemakers.

It is my feeling they should be given

sensitivity training, not only on racial and

religious differences, but on human rela-

tionships since they project a school's

image to the outside world .

Allen Cohen

Senior Advisor

Chinese-American Planning Council

Contacts, PINS.

I suggest you publish the postal and

Internet addresses of all the groups you

profiled in your article on 'Net organizing

["Downloading Democracy," May 1996].

It's about access, isn't it? Thanks for the

great article.

Tim Siegel

Center for Community Change

Kim Nauer replies: Good idea. In the

interest of promoting telecommunications,

however, I am including only e-mail

addresses and, for the techno-phobic,

phone numbers. In order of appearance:

Ken Deutsch, Issue Dynamics Inc.,

deutsch@idi.net, (202) 408-1920.

Audrie Krause, Computer Professionals

for Social Responsibility, cpsr@cpsr.org,

(415) 322-3778.

Martha Ross, SCARCNet,

ai002Q@advinst.org, (202) 659-8475.

Nalini Kotamraju, Stand for Children,

103661.222@compuserve.com,

(202) 234-0095.

Nathan Henderson-James, ACORN,

resgeneral@acorn.org, (202) 547-9292.

Jonah Seiger, Center for Democracy

and Technology, jseiger@cdt.org,

(202) 637-9800.

Barbara Duffield, National Coalition for the

Homeless, nch@ari.net, (202) 775-1322.

Anthony Wright, Center for Media

Education, infoactive@cme.org, (202)

628-2620 .

CITYUMITS

winnerf!!

THE

DEADLINE

CLUB,s

TOP JOURNALISM

AWARD FOR 1996

PRESENTED BY

THE NEW YORK CHAPTER OF THE SOCIETY

OF PROFESSIONAL JOURNALISTS

Senior Editor KIM NAUER, Editor AND REW WHITE

and former Senior Editor JILL KIRSCHENBAUM

were awarded the James Wright Brown Award recognizing "the news

organization that renders outstanding public service to its community"

for "Profits from Poverty," our May 1995 series that exposed

the private fmanciers who operate behind the scenes in poor

communities, reaping huge profits from slum properties.

JUNE/JULY 1996

WHAT WILL CITY LIMITS

UNCOVER NEXT?

Social Policy magazine and

The Learning Alliance present:

IS there a

politics

beyond

liberal

and

conservative

New York City-Saturday, June 15

JOin the country's cutting-edge thinkers and

activists for a fresh, bold, day-long conference

setting aside politics as usual. Come help lay

the groundwork for a dynamic post-liberal,

post-conservative political philosophy.

info: 212/226-7171 or

www.sodalpolicy.org

($15, $25, $35, sliding scale; no one rurned away.)

ro-sponsors: Center for a New Democracy, Cenrer for

Democracy and Cirizenship, Center for Human

Rights Education, Center for Living Democracy,

City Limits, Environmental Action, Grassroots

Policy Projecr, Insrirure for Women Policy

Srudies, National Cenrer for Economic and

Securiry Alrernarives, Tht Ntighborhood

Works, The New Pany, New York Online,

Tht Progmsivt Populist, Third Foret,

The Union Insriture, Who Cam?

PUBLIC HOUSING STEALTH ATTACK

blue on us," the veteran

administrator says. "But its

not necessarily bad news ....

We look favorably on any fed-

eral legislation that leads to

deregulation."

go

~

'"

BRIEFS i

. ,

Students cast

protest ballots in a

mock election on

the steps of the

Bronx County

Courthouse.

Short Shots

Tenant advocates knew

the housing bill passed by the

House of Representatives

last month meant bad news

for poor people, but no one

suspected the bill contained

a stealthy doomsday clause

that gives New York officials

the right to entirely dismantle

the city's public housing sys-

tem.

The provision, written into

the housing bill by Republican

Rick Lalio of Long Island,

specifically exempts the New

York City Housing Authority

from almost all federal public

housing regulation for at least

three years. -That means the

sky's the limit in terms oftear-

ing public housing apart:

says Billy Easton, executive

director of the New York State

Tenants and Neighbors and

Coalition.

i BROOKLYN CON6RESSMAN

erals among Newtered

Democrats in the l04th

Congress, unexpectedly

voted the GOP party line on

an illiberal overhaul of pub-

lic housing policy (see item

above). Could Chuck's

wagon be veering to the

right?

'" 0IARIfS SOIUMER MAY

run for governor two years

from now, but don't expect

him to do his baby-kissing

in the corridors of public

housing projects. Schumer,

one of the more spunky lib-

"NYCHA could tear build-

ings down," he adds. -They

could drive poor tenants out

and replace them with mid-

dle-income people and never

build any more low income

units .... They could force poor

people out and give them

vouchers-even though

there's practically no afford-

able private housing in New

York City."

The Lalio bill, which repre-

sents the most significant

overhaul of federal housing

policy in six decades, puts

$6.3 billion in federal housing

subsidies in block grants to

states. For the first time, it

also allows public housing

authorities to evict poor ten-

ants simply because they

could not afford to pay rent

increases. It passed the

House with broad bipartisan

REPUBUCAN SENAH MAJOR-

ITY lIADER JOSEPH BRUNO

has abandoned Governor

George Pataki to ally with

Democratic Assembly chief

Sheldon Silver in a fight

against the governor's deep

cuts to welfare and educa-

tion. The news makes even

Pataki's growing list of ene-

support by a 315 to 107 vote

May 9.

But the clause singling out

the city was carefully hidden

in a section that allows 200

local housing authorities to

opt into a public housing

deregulation plan. The bill

specifically targeted munici-

palities with "more than

99,999" public units for

mandatory deregulation.

NYCHA, with 164,000 public

apartments, is the only hous-

ing authority large enough to

fit that description.

There has been much

speculation that NYCHA offi-

cials helped insert the provi-

sion, a contention denied by

an authority spokesman. Still,

a high-ranking agency official

tells City Limits that the Lalio

bill isn't exactly unwelcome.

"It was dropped out of the

The bill now goes to con-

ference committee with the

Senate, which passed its own

housing bill in January. The

Clinton administration has not

said it will support the Lalio

plan, but Democrats concede

that a measure that gets

tough on public housing ten-

ants will be hard to fight in a

presidential election year.

"I don't think the President

is willing to go to the mat on

low income housing," cau-

tions one House staffer with

close ties to the White House.

"I think [HUD Secretary

Henry) Cisneros already

thinks Lazio's version is fine

the way it is .... So there's a

chance this might become

law." Glenn Thrush

WISDOM IN AOION

A news photographer

scrambled on the steps of the

Bronx County Courthouse try-

ing to align the figure of a

sleeping 7 year old with the

marble-etched quotation above

the doors: "Government is a

contrivance of human wisdom

to provide for human wants."

If only it were so. This

neighborhood is home to

Community School Board 9,

one of the most corrupt and

undemocratic of the 32 boards

in the city, and its only con-

trivance is to get reelected.

But on May 7- school

board election day- about

1,500 parents, students, and

clergy from South Bronx

Churches, a community organi-

zation, marched down the

Grand Concourse to call for the

elimination of the boards and

mies feel bad for the guy.

First, Rudy leaves him for

Mario; than his lieutenant

governor deserts him for her

conscience. Now Joe's gone.

So much for the Man from

Peekskill's amiable reputa-

tion. Rumor has it "Pataki"

means "doesn't play well

with others" in Hungarian.

the dethroning of Board 9's

longtime president, Carmelo

Saez.

"Jesus blessed the chil-

dren," thundered Father John

Grange of Mott Haven's St.

Jerome's Catholic Church.

"When people tried to keep him

away from them, he got angry!"

The crowd roared.

But if the rally was a sign of

community strength, the elec-

tion that took place atthe same

time was not. Although the SBC

has registered 4,800 new voters

since the beginning of the year,

the only five candidates on the

ballot were Saez allies. (At

press time, schools Chancellor

Rudy Crew had suspended

Saez for the second time in six

months. And the results of the

election had been delayed by a

computer glitch.)

At least one person attend-

ing the protest didn't care much

about the politics. Maria Plaza,

a 15-year-old 8th grader told a

bystander she was worried her

sister was about to drop out of

school. "She's 14 and they put

her in special ed," she said.

"During the day they just let her

roam around the halls. They

don't care .. .. What kind of edu-

cation is that?" Glenn Thrush

CITVLlMITS

BUDGET MENU: RUDY'S COLD CUTS

he first hints of trouble can be found in the opening pages of Mayor Giuliani's most recent budget

proposal for the upcoming fiscal year, which begins July 1. The table of contents lists all the wrong

page numbers, as well as appendices that don't exist.

Will Giuliani's budget numbers be any more accurate as the year plays out?

Whatever happens, there will certainly be major reductions in services for low and moderate

income New Yorkers. While tax cuts have been delayed and the city budget is slated to grow to $32.7 billion

from $31 .1 billion, the budget ax will still strike everything from sanitation and libraries to welfare and home-

less services. The following is a summary of some of the notable impacts:

Welfare

he proposed half-bil-

lion dollar cut to city

welfare spending-

about one-quarter of

that in city funds-

depends on reducing the welfare

rolls by about 90,000 people. By

June 1997, The administration

hopes to cut the number of peo-

ple receiving Aid to Families with

Dependent Children by 52,665;

Home Relief rolls by 35,633. HRA's

staff will be slashed by 1,100

positions.

Giuliani's welfare budget plan

depends on passage of most of

Governor Pataki's own budget

proposal to reduce welfare ben-

efits and impose time limits. But

Pataki's budget is currently

locked in Albany negotiations

and is likely to be revised.

The mayor's workfare pro-

gram, NYC WAY, will be

expanded to include AFDC fam-

ilies. And many other parts of

the city budget appear to rely

on welfare recipients providing

services. Administration offi -

cials have already testified in

public hearings that some

parks and civilian police

department slots will be filled

by welfare recipients.

Still, Giuliani's previous

attempts to cutthe rolls have not

occurred at the city's projected

rate. In FY 96 the city spent $42

million more than planned for

public assistance and for FY 97

that number is expected to be as

high as $82 million.

Homeless Services

he Giuliani budget pro-

jects a decrease in

shelter populations for

1997, despite the

steady increase in the

number of single men entering

the system last year. And there

still aren't enough shelters to

meet the city's need. In May, the

JUNE/JULY 1996

mayor and city were fined $1 mil-

lion for failing to move homeless

families out of the Bronx intake

office to shelter rooms within 24

hours as required by law. The

Coalition for the Homeless con-

tends that growth in the shelter

population has been driven by a

growing number of welfare

recipients cut off the rolls.

The mayor's plan would

reduce staff atthe Department of

Homeless Services by more than

700 employees, a 30 percent

reduction. Some of this loss

would be made up by the privati -

zation of seven city shelters-

but not all. Cuts include an $11

million (6.B percent) reduction in

services for single adult men.

Family shelters can only hold

about 5,BOO homeless families

and the number of permanent

apartments available to families

in the shelter system continues

to decline. In Rscall994, the city

helped more than 5,400 home-

less families find new homes; the

Fiscal 1997 projection is 3,960.

"These reductions are the very

reason the city was just held in

contempt," says Steve Banks of

Legal Aid's Homeless Family

Rights Project

City Hospitals

o agency is feeling

the knife more than

the Health and

Hospita l s

Corporation, which

administers 11 public hospitals

and 20 other health care facilities

that accounted for almost 5 mil-

lion patient visits last year. The

city's annual contribution to HHC

has shrunk from $350 million

three years ago to a mere $37

million in next year's proposed

budget. Coupled with state

Medicaid cuts, HHC stands to

lose almost half a billion dollars

from its current$I .2 billion in rev-

enues. The corporation is now

almost entirely funded by

Medicaid.

Current city funding doesn't

even cover the approximately

$60 million in services the hospi-

tals provide police officers and

prisoners. And the city's commit-

ment to capital improvements in

its hospitals- which had de-

creased from $204 million in 1992

to $17 million in FY 199B-has

now officially disappeared.

HHC sources say the agency

will likely lose B,ooo of its 3B,ooo-

member workforce, a whopping

reduction of 22 percent. Last

month, HHC President Luis

Marcos began the blood-letting

by announcing the layoffs of

2,700 employees, including doc-

tors, nurses, administrators and

lab technicians. For patients it

will, at the very least, mean

longer waits in emergency

rooms and clinics. At worst. it

could mean a shortage of quali-

fied personnel at a time when

health care for uninsured work-

ing people is getting harder to

find.

Sanitation

ore garbage will

pile up on corners

if Giuliani's plan to

cut litter basket

collection in half

is approved. The mayor is seek-

ing to reduce the sanitation

department's budget by nearly

$100 million, in part by reducing

garbage collection from schools

and public housing.

Most strikingly, he would cut

away a massive piece of the

agency's recycling program. The

recycling proposal would cut

back pick-up to once every two

weeks in most of the city and

eliminate the recycling of mixed

paper-just recently implement-

ed in parts of Brooklyn, Staten

Island and the Bronx. The

administration will continue to

fall afoul of state and city laws

that require the city to be recy-

cling 40 percent of its trash by

late 1997. At last count, the actu-

al rate was about 14 percent

Housing

he Department of

Housing, Preservation

and Development,

which accounts for

only 7 percent of the

city's capital spending, is slated

for a 35 percent cut under the

plan-a loss of $59 million.

To make the reductions, HPD

is no longer bankrolling many of

its smaller neighborhood revital -

ization plans. But the city is also

taking a bite out of programs

central to the agency's mission

of preserving and maintaining

low income private housing. The

Article BA loan program, which

gives landlords low-interest

loans to repair pipes and heat-

ing systems in apartment hous-

es, has been cut by nearly one-

third to $3 million; the

Participation Loan Program is

losing $800,000.

The Neighborhood Pre-

servation Consultants-local

nonprofit housing experts hired

by HPD to provide technical

expertise-are being given

increasing responsibilities with-

out the cash to cover them.

In the meantime, the city's

effort to sell off its tax-delin-

quent housing stock rolls on.

Capital spending on the Tenant

Interim Lease program, which

bankrolls tenant-owned cooper-

atives, remains steady at $20

million. The Neighborhood

Entrepreneurs Program, which

rehabs buildings for sale to for-

profit landlords, is one ofthe few

HPD programs to be boosted-

to $57 million, one-fifth of the

agency's total capital budget

Kierna Mayo Dawsey.

Andrew White and Glenn Thrush

-

PROFILE ~

,

Deni s Cretinon

(right) has worked

with the residents

of one block i n

East New York

for five years.

Worldly Ambitions

For this crew of Europeans, serving the poor in East New York

means spending years building trust and documenting lives.

By Isabelle de Pommereau

I

t has been five years since Rosalyn

Little moved with her children from

the Prince George welfare hotel in

Manhattan to a city-owned building

in East New York. Like many of her

neighbors on Montauk Avenue, Little's life

since then has been punctuated by meet-

ings and phone calls with people paid to

help her-the city's housing bureaucrats,

social workers, school teachers. They

flicker in and out of her days, one person

quickly replacing another, few taking the

time to say hello, let alone have a mean-

ingful conversation.

Little has been talking with a couple of

more responsive poverty workers, howev-

er. They happen to come from France.

Denis and Babette Cretinon, two leaders of

the Fourth World Movement-an organi-

zation based in the low income suburbs of

Paris that has outposts worldwide-have

visited her block with other volunteers

every Tuesday for the last five years in a

van filled with books, computers and craft

tools. The street library is a diversionary

tactic of sorts: while some volunteers work

with the children, helping them read or

build projects, others chat with Little and

her neighbors, catching up on the past

week and encouraging them to "docu-

ment" their lives for people from other

walks of life who do not understand the

true nature of a life lived in poverty.

At the movement's urging, Little has

spoken at the White House and the United

Nations, outlining her daily routines and

her frustrations with America's social ser-

vice system. It's the least she could do,

she says. "They're my rock," Little adds

in a low voice. "Sometimes you meet peo-

ple who pretend they care about you, but

they don't. But there's nothing phony

about the Fourth World."

The Fourth World Movement-the

name refers to the chronically poor who

live in every part of the world-is almost

invisible in the shadow of much larger non-

profit organizations here in New York City

and across the United States. But in France,

where the antipoverty organization was

born 39 years ago, the movement has

gained considerable influence in social pol-

icy and advised national leaders on ways to

help the poorest of the poor-those who

were born into poverty and have been

unable to use that country's rich social ser-

vice system to climb out. The organization

claims to have a special vantage point:

Instead of "serving" people with housing

or social services, full-time volunteers

commit to working in a community for

years, moving into the neighborhood and

understanding the culture. Workers offer

local residents little in the way of tangible

benefits-most live near the poverty line

themselves-but they try to give people a

sense that they're not alone, that they're

part of an international network of people

who happen to be very poor.

"Part of what they say is, no matter

who's been in power, the fourth world's

been screwed-whether it's the socialists,

communists or capitalists," says Daniel

Kronenfeld, executive director of New

York's Henry Street Settlement and a

member of the movement's U.S. board of

directors. ''They want to document the

lives [of the poor] so those in power will

really understand poverty and change the

way they deal with it."

Posltlv_ Pr_Judlc_

The Fourth World Movement was

founded in 1957 by Father Joseph Wre-

sinski, a Roman Catholic priest who grew

up poor and was assigned to an impover-

ished suburb of Paris. Upon arriving, he

immediately expelled a group running a

soup kitchen in a shantytown where he was

working, thinking it made people too

dependent. Instead, he set up a library and

opened a research center, hoping to con-

vince the government that extreme poverty

is a violation of human rights and rallying

people to join what's become an interna-

tional non-sectarian movement. In 1964, he

opened the organization's New York office

on the Lower East Side. Others have fol-

lowed in Washington, D.C. , and New

Orleans. The group's 350 full-time volun-

teer leaders work and live with the poor in

more than 20 countries around the world.

In France, the Fourth World Movement

has brought national attention to the fact

that hundreds of thousands of French kids

were illiterate, helping persuade the gov-

ernment to enact reading programs for poor

children. In 1979, President Valery Giscard

d'Estaing, a conservative, appointed one of

the movement's leaders to the govern-

ment's Economic and Social Council, a

third house of government charged with

recommending social policy. Eight years

later, after considerable debate, the council

endorsed a plan written by Wresinski call-

ing for a guaranteed income for all resi-

dents, as well as housing, health insurance

and legal support. In 1989, the French gov-

ernment enacted a key part of the plan, leg-

islation strengthening the nation's consid-

erable social safety net with a first-ever

CITY LIMITS

mandated minimum income.

The Fourth World Movement has seen

none of this success in the United States.

The movement here remains politically

weak, Denis Cretinon admits. The prob-

lem, says his wife Babette, is that most

Americans view impoverished people with

too much hostility, absorbing only the

most superficial details about how they

live. "Society just judges, judges, judges,"

she says. "But they don't know anything. "

That, argues Denis Cretinon, is why it is

important to have people report uncritical-

ly, with a "positive prejudice" rather than a

negative one. Fourth World volunteers

keep journals of their experiences in poor

communities, using the material later in

books and public testimony.

"We talk, for example, about the 'fem-

inization of poverty, '" he says. "It has to

be that way. It is the only way mothers can

get [welfare] payments for their children.

But when you take time and look, you see

that there is a man in that family. They

share in the housekeeping. They have a

real role. It just doesn't exist statistically.

"[People in poverty] always have to

wear a mask to get what they need. You

become what people need you to be to get

what you want. " Policy makers, he insists,

need to design laws offering low income

people help without forcing them to con-

form to traditional preconceptions.

StrMchH Thin

Driving a rusty van to haul their street

library, the Cretinons have been working on

two patches of Montauk Avenue in East

New York since they came here five years

ago. But the Fourth World Movement has

been a presence on this stretch far longer.

According to residents, volunteers have

been visiting every week for the last decade.

"You don' t see this type of thing on a

consistent basis," says Emma Speaks, a

mother of four who travels from the

Cypress Hills housing project every week

to bring her kids to Fourth World's mobile

center. "Week to week, you keep it in

mind. You look forward to it. You start

making plans and you build on it."

Angela Price's building used to be open

turf for dope dealers who'd stash their bags

of cash and crack into gaping holes in hall-

way walls, often leaving residents too fear-

ful to leave their apartments. Things have

improved since, she says, thanks to a police

crackdown. But Price and other tenants

also credit the Fourth World's consistent

JUNE/JULY 1996

presence, week after week, for luring ten-

ants out of their apartments and giving

them hope. "When the street library started

coming, the dealers moved right out and

didn't come back," Price says.

The Cretinons are the first to admit

their reach is limited. With an annual bud-

get of less than $l00,OOO--raised mainly

from individual contributions-and a

mandate to maintain contact as long as a

block wants them there, the volunteer

staff is stretched too thin to make much of

an impact. In America, where "move-

ments" are judged on results, people have

to ask, what are these volunteers really

accomplishing?

It's something deeper, more "mystical"

than literacy services or political organiz-

ing, says Daniel Kronenfeld. "I've worked

in agencies where you come and you go.

The funding comes and the funding goes.

You start a project, but as soon you're in

there, you're out of there.

"The Fourth World is not a program that

begins and ends. Once they've made con-

tacts with families, they maintain them."

On Montauk Avenue, 8-year-old Erica

Babilonia doesn't know where the book

van comes from and she doesn't care. With

the volunteers' paint and brushes, she's

painted a slat of wood with colorful letters.

Her message: "Peace and Love. " The wood

will be built into a big flower pot contain-

ing tulips and plants-and it will stay on

the block for a long time to come, just like

the Fourth World Movement, a bright

splash of spring brightening a bleak:

Isabelle de Pommereau is a regular con-

tributor to the Christian Science Monitor.

Nev# York La"'Yers

for the Public Interest

provides free Legal referrals for community based and non-profit groups

seeking pro-bono representation. Projects include corporate, tax and real

estate work, zoning advice, housing and employment discrimination,

environmental justice, disability and civil rights.

For further information,

call NYLPI at (212) 727-2270.

There is no charge for NYLPI's services.

FINDING THE GRASSROOTS:

A directory of more than 250 New York City activist organizations.

"A superb and necessary resource."

-Barbara Ehrenreich

"A wonderful guide for coalition building ... A resource

permitting us to transcend race, gender, sexual

orientation, class and other boundaries."

-Manning Marable

Available for $10 plus $3 mailing costs. Checks to: North Star Fund

Mail to: North Star Fund, 666 Broadway, 5th Fl., New York, NY 10012.

Call 212-460-5511 for more information.

s

@CTIVISM t

,

Web Research Central

The Internet is loaded with information on government, politics and corporations.

Here are nine gold mines for organizers and advocates. By Steve Mitra

W

ith the explosion of

information on the

World Wide Web, the

question now is not

whether the information

you want is available-it's how you get to

it. Of course there are the "Yahoos" and

"Altavistas" of the Web-"search en-

gines" that purportedly sort things out for

you. But by their nature these indexing

tools are incomplete. And you wouldn't

want to miss many undisputed gold mines

that can help you learn more about your

neighborhood, your elected officials,

Washington politics and national activism.

Covernment

Starting locally, the New York State

Local Government Telecommunications

Initiative web site (http://nyslgti .

gen.ny.us:80!) has state information orga-

ful job training projects, and the increasing

use of home health care in the Medicare

population. The reports also expose flaws

in federal programs and outline possible

reforms. The site even maintains an e-mail

"listserv" that alerts you to reports as they

are released.

The FEC site includes so much cam-

paign finance information that it will either

make you drool with glee or leave you

hopelessly confused. AU candidates run-

ning for election have a summary record

that includes campaign receipts, money

received from individuals and different

categories of Political Action Committees

(PACs), the amount candidates spend,

their cash on hand, and debts owed by the

campaign. But you can also get details

sorted by contributors, both individuals

and PACS. Best of all, the site is current

for the 1995-96 election cycle. The text-

hud.gov/local/nyn/nynmailk.html).

One of the few good things to come out

of the 100th Congress, the grandly-named

"Thomas" (as in Jefferson), is at

http://thomas.loc.gov.This is one of the

best free sources of information on con-

gressional activities. It includes searchable

daily proceedings from the floors of the

House and Senate; summaries and legisla-

tive histories of bills and amendments, and

lists of laws and vetoed bills.

Business and Banking

but the type of published information varies.

As of May 6, every corporation that

sells stock on the public exchanges must

file its annual and quarterly reports with

the Securities and Exchange Commission

via computer. As a result, the "Edgar"

database of corporate information is more

up-to-date than ever before. If you 're

doing company research, what you want is

probably here (http://www.sec.gov/

edgarhp.htm), including extremely

detailed reports on the company's history,

owners, future plans, revenue and debts.

The reports can be downloaded directly to

your computer.

[.M

nized by county. Proflles of each borough

in New York include the census snapshot,

demographic and business trends. Also

included are maps showing race, income,

education, and occupation distribution

throughout the state.

Just about every federal agency is on the

Web, but the amount and type of published

information varies. One important feature

most include is a directory with names and

numbers of local agency offices. A good

place to access this universe of information

is the FedWorid site (http://www.fed

world.gov!). Another useful feature is a col-

lection of abstracts of recently released

reports by different agencies.

Two federal sites stand out for their

depth: the Web site of the General

Accounting Office (GAO) and the Federal

Election Commission (FEC). Both publish

material that's often the basis of front-page

stories for major newspapers. Now you

can do what reporters do, and dive right in

to the source material from your home

computer.

The GAO's probes reveal comprehen-

sive information on thousands of topics

(find the site at http://www.gao.gov).

Recent reports covered subjects like the

benefits of economic development pro-

grams, the common strategies of success-

based version of the FEC site is at

http://www.fec.gov / 1996/txindex.html.

(The slower, graphics version is at

http://www.fec.gov).

Of course, there are ways to hide influ-

ence-peddling. For example, when corpo-

rations ask (or coerce) employees to

donate to a particular candidate, they can

"bundle" the donations. Exposing this tac-

tic requires a sophisticated analysis of con-

tribution patterns. Mother Jones magazine,

in collaboration with the Center For

Responsive Politics, did this recently, and

they've put their database on the Web in a

searchable format. It's at http://www.

motherjones.com/coinop_congress/mojo_

400/search.html.

The Department of Housing and Urban

Development's Office of Policy Develop-

ment and Research has put its research

reports on the Web-covering everything

from lead paint hazards to the long-term

prospects of HUD-sponsored housing.

They're all available at http://

www.huduser.org/. To search the database,

go directly to http://www.huduser.

org/cgi/huduser.cgi. And the home page of

the New York HUD office (http://www.

hud.gov/local/nyn/nynhome.html) has local

program information as well as e-mail

addresses of all employees (http://www.

When banks in the New York area

plan to merge or open or close branch

offices, they must first submit an applica-

tion to the Federal Reserve Bank of New

York and the public gets a chance to offer

comments on the proposal. This is the

time when neighborhood groups force

banks to pay attention to poor communi-

ties by testifying before the regulators.

Keep up with the schedule of applications

at http://www.ny.frb.org/.

Politics

Project Vote Smart (http://www.vote

smart.org) is arguably the best Web site

covering U.S. politics. Find out every-

thing from the status of legislation on

important issues to detailed biographical

information on members of Congress. Of

note are answers by the legislators them-

selves to a series of "No-Wiggle Room"

questions, as well as performance evalua-

tions from special interest groups from the

Christian Coalition to the Children's

Defense Fund .

Steve Mitra is an editor of a new political

on-line project in Washington, D.C.

CITY LIMITS

ADX Company

773 S. Cote Rd.

Queens. NY 11360

..... EABP'au

1 I i i I ' ~ Now 'lbll< 11M5

FOR __________________________________ ___

Using our new Small Business Credit

Line is as easy as writing a check.

Because that's all you have to do.

Now you can take advantage of

pre-paytnent discount opportunities,

buy a new copier or computer, cover a

temporary cash flow need - just by

writing a check on your Small Business

Credit Line;* Once the line is established

*Based upon credit approval.

no additional approvals are required to

use it. Paying back your loan

automatically restores your available

credit line for future needs.

EAB's Small Business Credit Line.

A practical, affordable, flexible line

of credit that you can use anytime,

anywhere, simply by writing a check.

Call Thomas Reardon at (516) 296-5658.

Business Banking

:>1996 ABe Member FDIC Equal Opportunity Lender

s

PIPELINE ~

,

f

Harmony Rising

Parents and foster children raise their disparate voices in a call

for change in the child welfare bureaucracy. By Seema Nayyar

"They dangled my son in front of my face

like some carrot. They'd say, 'If you want

him back, you have to be clean and do all

of these steps,' like check into a drug

rehab, take parenting skills classes and

make your visits. But sometimes they

didn't have enough room in the classes.

Or enough money to provide the services.

They'd blame you and say, 'You're not

ready."'-Nancy Sanchez Wright, 39

"The whole time that I was in the system,

there wasn't anybody there to talk to. I

had no say about where I would live; no

one told me I had rights as a child."

-Sabrina Hines, 19.

N

ancy Sanchez Wright and

Sabrina Hines have different

reasons for disliking the

child welfare system.

Sanchez Wright is a biologi-

cal parent who had three children taken

away by city social workers; Hines is a

foster teen who spent 10 years of her

childhood in the bureaucratic system. For

different reasons, both women harbor a

certain resentment for the city's child wel-

fare agency. But now, the voices of both

women are resonating as one in an effort

to reform the child welfare system and

make it more responsive to people like

themselves.

Fueled by deep-rooted anger and frus-

tration over broken promises and humiliat-

ing experiences, the voices of biological

parents and foster kids are reaching a

crescendo. There's a movement afoot to tie

together complaints of disparate groups

within the child welfare system and create

a common platform for reform.

But it's not exactly a cohesive coalition

just yet; it's more of an emerging move-

ment: The newly-formed Child Welfare

Organizing Project is rallying biological

parents to gain political clout. The Child

Welfare Fund, a group that gives $1 rnil1ion

a year to child welfare reform, is testing a

project that would give biological parents

more of a say with agencies that place kids

in foster care. Youth Communication,

which publishes a magazine for foster kids,

recently released a book written by

teenagers chronicling their experiences in

the foster care system. And this month,

University Settlement, an advocacy group,

will present a comprehensive, 30-page

"Bill of Rights and Responsibilities" to the

mayor in hopes that it will be used as a

guide by those in the child welfare system.

The booklet was written by biological par-

ents, teens and foster parents.

While all these different groups have

competing interests, there are signs that

some are willing to work together to pres-

sure the Administration for Children's

Services (ACS) and private nonprofit fos-

ter care agencies to handle their cases with

more sensitivity and care. "I'm not a foster

care basher," says AI Desetta, editor of

Foster Care Youth United, the magazine

published by Youth Communication and

written by kids in foster care. "It's a bureau

that, in some ways, has been given an

impossible job of replacing the family. But

you can't use that as an excuse. The sys-

tem can't continue the way it is."

R.unltlng Chlldr.n

Six months of public and press atten-

tion focused on the child welfare bureau-

cracy following the death of Elisa

Izquierdo last fall has led to reforms at one

level of ACS. Commissioner Nicholas

Scoppetta has sought to make caseworkers

and their supervisors more responsive to

reports of abuse and neglect and more

accountable for the safety of children

known to the agency. Yet, while outside

experts have been calling for better train-

ing of caseworkers, little attention is given

to ACS's other main mission: reuniting

children with their families, or moving

them to new, safe homes.

Most children removed from their par-

ents by ACS caseworkers are quickly

turned over to private nonprofit organiza-

tions contracted by the city to place kids

in foster care, supervise foster parents

and provide biological parents with coun-

seling.

Mabel Paulino, director of the Child

Welfare Organizing Project, a one-year-

old group dedicated to helping biological

parents, surveyed 42 of the city's 53 foster

care agencies to see whether clients had

any significant role in making decisions

about their own lives. The answer, Paulino

says, was an across-the-board no. "The

[biological] parents don't know what's

going on, they don't have participation in

their children's planning, no say in visita-

tions. There's little effort being made to

involve them," she says.

The one exception is the Westchester-

based St. Christopher's-Jennie Clarkson

agency, which supervises about 1,600

New York City foster care children. Three

years ago, the agency began an experiment

with the support of the Child Welfare

Fund. Among the changes: the agency's

caseworkers are on call 24 hours a day,

seven days a week; drug rehabilitation ser-

vices are provided immediately upon

request; parent representatives sit on the

organization's personnel committee and

have a say in hiring and firing decisions,

and they will soon have a designated seat

on the board of directors. Most important-

ly, each parent can choose to have their

own advocate within the agency, usually a

fellow parent who has overcome her own

problems with the child welfare system.

"We've shifted from a child focus to a

family focus and incorporated parent feed-

back at every level," explains Jeremy

Kohomban, director of family services at

St. Christopher's. "We're no longer treat-

ing parents as second class citizens."

The agency's principles and guidelines

read as if they were written by enraged

clients: "Parents have a right to challenge -

the agency without fear of reprisal .... The

parent has a right to visitation and sched-

uled meetings that do not conflict with

their work schedules .... The role of the fos-

ter parent is not just to care for the child,

but also to assist the parent in staying

closely connected to his/her children."

Sanchez-Wright, a former crack

cocaine addict, had three children taken

away from her soon after each was born.

After the third time, she decided to clean

up her act and promised to stay off drugs.

In exchange, St. Christopher's promised to

return her third child. Now, she and the

agency work together toward the same

goal: reuniting families. As a parent advo-

cate employed by the organization, she

accompanies agency workers to other par-

ents' homes. "When I visit people, I tell

them, 'I did it. You're not any worse than I

was.' Then I bring them to my home and

let them see life now."

For Jo-Ann Johnson, being a parent

advocate is an issue of experience, decen-

cy and credibility. "I dido't like strange

CITY LIMITS

people corning into my house and looking

me over. It's insulting," says Johnson, who

was separated from her daughter, Maari, 5,

for three years. "But when a recovering

addict goes to another addict's house, we

can share our experiences."

As a result of the changes, St.

Christopher's has reduced foster care stays

from 1993's average of 2.35 years to 1.75

years today, Kohomban says. Even more

telling are the agency's recidivism num-

bers. Nationally, almost one-third of all

children returned to their biological parent

from foster care ultimately end up being

taken away again. St. Christopher's has

gotten that number down to

less than three percent.

More than one-third of

the agency's staff has been

replaced since 1993-by

people willing to abide by

the new rules. "I have a non-

negotiable position on this,"

Kohomban says. "If you

don't agree with the philoso-

phy that parents should be

included, then leave. The

ones who have stayed have

made the shift. I wish I

could say we did something

magical. We just opened the

door to sharing the power."

Dlv.rg.nt Croups

Many of the most elo-

quent critics of the system

are the foster youth them-

selves. Zcherex Solis, now

19, lived for nearly four

years in a residential treat-

ment center for young peo-

ple deemed "innappropriate" for foster

care by the agencies. There, she says, case-

workers refused to give her critical infor-

mation about her own case. They wouldn't

even tell her the name and phone number

of her court-appointed lawyer. "I would

get, 'I don't know' or 'I can't get that

information now,'" Solis says. She finally

got in touch with the Youth Advocacy

Center, a three-year-old foster child advo-

cacy group. Its executive director, Betsy

Krebs, found her a new lawyer who helped

Solis find a foster mother in Brownsville.

Now, Solis helps other teens navigate

the system, testifies at state and city hear-

ings and speaks to social workers learning

about child welfare issues. "Most of the

time when we go to social work school and

JUNE/JULY 1996

ask what they've heard about us, they say,

'We've heard that you're troubled kids.'

That's not true. We tell them kids in foster

care should be listened to and not forgotten

about. The kids in the system are the real

child welfare experts."

In February, the Child Welfare

Organizing Project co-sponsored a closed-

door summit bringing together divergent

groups affected by the system. The day-

long event included biological parents,

foster children and foster parents.

Participants were not able to agree on

many issues, and some of the sessions

were rancorous, but by the end of the day

many of them agreed to join a coalition to

formulate a platform for child welfare

reform.

Skeptics question whether a collective

voice will triumph or cower under the

pressure of such diverse interests. It's one

thing to agree that change is necessary. But

it's quite another to decide what those

changes will be. Meryl Berman, director

of community development at University

Settlement on the Lower East Side, says

she wouldn't have believed it, yet all of the

various voices seem to be forming a har-

monious chorus.

Starting two years ago, volunteers from

two University Settlement groups, Women

as Resources (WAR) and Youth

Empowered to Speak (YES) began meet-

ing every week to put together a manual to

help parents and children deal with child

welfare investigations. Co-authors of the

resulting "Child Welfare Bill of Rights and

Responsibilities" included people like

Cheryl Moran, 36, whose child was once

taken from her by the city; Norma

Hubbard, 27, a foster mother; and Chaem

Dudley, 16, who claims that overly-zealous

caseworkers almost ripped apart her fami-

ly. "At some meetings you thought people

would never talk to each other again,"

Berman says. But at others, she adds, "mir-

acles would happen. People would sudden-

ly discover that they had something in

common with people they thought they

hated." This month, the guide will be pub-

lished and presented to the mayor.

Yet for the moment, issues like respon-

siveness and sensitivity are not even on the

table at ACS. Scoppetta's agenda, as of

late last month, detailed plans for improv-

ing worker training, upgrading the com-

puter system and developing tighter links

with other agencies, like the police, who

are in a position to see and report abuse.

Advocates say Scoppetta would do well to

open up the system to the people it is

meant to serve and incorporate their points

of view-one voice at a time .

Seema Nayyar is a reporter/researcher

for Newsweek.

Meryl Berman

(center) and the

co-authors of a

new manual on

how to deal with

the child welfare

system represent

a wide variety of

experience.

PIPELINE i

,

"You're enclosed,

and you can't get

away from pollu-

tion in Hunts Point,

says Antoinette

Mildenberger, a

school teacher

who has lived in

the neighborhood

for 47 years. Gar- 0

bage fires (below) I

are one of the '"

many air quality ~

problems here. ~

Air Assault

Poor health in Hunts Point may have more to do with pollution

than poverty. By Kemba Johnson

T

hese days, whenever Antoinette

Mildenberger steps out of the

building she's lived in for the

last 47 years, she fmds herself

surrounded by garbage.

To the right, Triboro USA Recycling.

To the left, Delmar Waste Management.

Behind her, a vacant lot where homeless

men and women bum plastic and rubber

coatings off salvaged wire so they can sell

the copper that's inside. Today,

as she walks past this lot, thick

gray smoke from the latest air ,

assault rises into the sky. She ,

coughs. "It's like you're

enclosed in it and you can't get

away," says Mildenberger. She

coughs again.

Mildenberger coughs a lot

but that 's not unusual in Hunts

Point. Neither are heavy nose-

bleeds, rashes, chest pains,

chronic colds and asthma. "We

don't get common colds," says

Eva San Jurjo, another Hunts

Point resident. "We get kids

with bronchial problems,

wheezing problems. They end

up in the hospital. It's really

scaring us."

Hunts Point residents have

long known that their neigh-

borhood is home to alarmingly high asth-

ma rates. At Lincoln Medical and Mental

Health Center, which serves the South

Bronx, 15,000 people visited the emer-

gency room for asthma last year. Some

2,500 were hospitalized-more than six

times the national average-and 22 died-

more than 10 times the national average,

says Dr. Harold Osborn, director of emer-

gency medicine at Lincoln. These trends

alone are a clue that air-borne pollutants

are a real problem, he says. "There's some-

thing in the air that's irritating."

Researchers are still not entirely clear

on why asthma rates are so

high in low income neigh-

borhoods like Hunts Point,

which has a median house-

hold income of about

$7,000 and is part of the

poorest community district

in the city. Studies by the

National Institutes of Health

point to indoor air pollution

as the prime suspect, how-

ever, including dust mites,

cockroach body parts,

rodent infestation and even

poor ventilation from

kerosene heaters and old

gas stoves.

Yet many Hunts Point

people are convinced

there's more to it than that,

and point to the overwhelm-

ing number of waste plants

and other polluting facilities

in the community. Government environ-

mental regulators say that all of the

sewage-related plants they regulate are in

compliance with state and federal emis-

sions standards, but no research studies

have yet looked at the cumulative health

impact of so many transfer stations and

waste processing facilities in one area.

It's the chest pains and chronic nose-

bleeds that have residents feeling especial-

CITY LIMITS

No research studies have yet looked

at the cumulative health impact of

so many transfer stations and waste

processing facilities in one area.

the three-year-old plant is responsible for

some of the area's most noxious odors, a

fetid stench of "human waste and I don't

know what else. " Periodically, the smell

wafts through the community for days at a

time. Residents say it has caused children

to throw up on their way to school.

And still others report that the smell

has triggered asthmatic reactions. Charles

White, who lives near the plant on Faile

Street, worries that toxic substances may

be floating amidst the acrid smell. "There

is something in the air that no one is telling

us about," he insists.

ly nervous these days. After meeting each

other at an asthma-education session, host-

ed by The Point Community Development

Co. , Mildenberger, San Jurjo and a dozen

others compared reports of health prob-

lems in their families and realized there

might be serious health issues beyond the

respiratory illnesses they had long been

familiar with. As a result, they formed the

Hunts Point Awareness Committee in the

hopes of convincing neighbors, doctors

and city officials that answers had to be

found soon-and that the poor outdoor air

quality should be looked at first.

Call For Action

The point hardly seems worth arguing

in a neighborhood sitting alongside the

Bruckner Expressway, amidst more than

40 garbage and recycling facilities. And

the community's call for action has

spurred a response. The Environmental

Protection Agency will soon release

results from a month-long pilot study of

the neighborhood's air quality, a fIrst step

toward determining if the area's waste and

recycling facilities pose any special health

risks. Local physicians have also taken a

fresh interest in the subject, proposing new

research on the link between Hunts Point

pollutants and asthma.

Government agencies responsible for

environmental safety insist that air pollu-

tion isn't a problem in Hunts Point. Two

state Department of Environmental Con-

servation air monitoring units in the South

Bronx consistently report that the air con-

tains less than half the state-mandated lim-

its of sulfur dioxide, airborne particles and

other chemicals known to aggravate respi-

ratory problems, according to a department

spokesman. (The Department of Sanitation

refused to comment on their regulation of

waste transfer stations in the area.)

Neither air-monitoring unit is in Hunts

Point, however. And members of the

Awareness Committee remain uncon-

vinced. in addition to the many waste

JUNE/JULY 1996

transfer and recycling companies based

here, there is a city-owned sewage treat-

ment plant and de-watering facility.

Trucks, frequently uncovered, rumble

through the neighborhood constantly,

kicking up road dust and dropping debris.

And acrid garbage and tire fIres are an all-

too-common sight.

Air-Quality VIolations

State environmental officials counter

that these concerns are unwarranted. Stack

testing of the fertilizer plant shows regulat-

ed emissions well below state limits, and

the DEC says the odor does not pose health

risks. "There are lots of problems [that

cause respiratory distress], but to point a

fmger at one particular cause is a mistake,"

Most worrisome to some residents is

the New York Organic Fertilizer

Company, a sludge-to-fertilizer plant that

converts nearly three-quarters of the city's

treated sewage waste into fertilizer pellets

sold to farmers nationwide. San Jurjo says continued on page 34

~ F

of

NEW YORK

INCORPORATED

Your

Neighborhood

Housing

Insurance

Specialist

For 20Years

We've Been There

ForYou.

R&F OF NEW YORK, INC. has a special

department obtaining and servicing insurance for

tenants, low-income co-ops and not-for-profit

community groups. We have developed competitive

insurance programs based on a careful evaluation

of the special needs of our customers. We have

been a leader from the start and are dedicated to

the people of New York City.

For Information call:

Ingrid Kaminski, Senior Vice President

R&F of New York

One Wall Street Court

New York, NY 10005-3302

212 269-8080 800 635-6002 212 269-8112 (fax)

the

-

CITY LIMITS

n the box, you are only allowed two showers, one

shave and one pack of cigarettes a week, and that's

only if you behave. The sink runs cold, and the guard

brings a bucket of hot water once a day. You see just

a sliver of sky through a window across the gallery.

Food is slid to you through a slot in the steel door.

You sleep. You think a lot about the streets and the

people in the outside world. It makes you angry.

Sometimes you get delirious and forget whether it's day or night.

One hour out of every 24, you are let out of your barren cell, shack-

led, in handcuffs and heavily guarded. You go alone to an outdoor cage

Inmates locked in

solitary quickly find

that sanity can

be a fuzzy concept.

Sensory deprivation

is becoming a

common incarceration

technique-but it

may backfire on

New York City.

By Sasha Abramsky

and Andrew White

a little larger than your cell to jog in place and breathe the air.

To pass the time you read. The librarian comes around, but

you only get one book at a time, so you fish around the tattered

stock and try to frnd a fat one with all of its pages so it will last

the week.

Even reading won't necessarily help you keep your sanity.

"You know how you read a story sometimes and you think you're

in the story? In isolation, you really are in the stories you read. You

act them out," says Lynwood Jones, who spent 12 years upstate on

burglary, attempted homicide, weapons and drug charges. "You

find yourself talking to yourself unconsciously without even real-

izing it. You read yourself crazy." Jones lived for nine months in

the box, punishment for sticking a fellow prisoner with a shank.

Today, one year out of prison, he is a counselor at Fresh Start,

a program for inmates and former inmates of Rikers Island. He

JUNE/JULY 1996

says he believed in God so strongly that he was able to get through

the long period of near-total isolation and emerge from prison to

build a new life for himself working with other ex-offenders.

Jones knows, however, that most other troubled inmates have

not done so well. Punitive isolation has badly damaged some men

and women, particularly those who are psychologically or mental-

ly impaired-a description that fits a significant number of the

inmates in New York State prisons. A few have gone on to kill peo-

ple after their release.

In New York, use of isolation units in state prisons is up by

more than 60 percent in just five years, even as funding for reha-

bilitation programs such as drug treatment and job training has

been reduced. At any given time, more than 2,100 inmates are

locked up in the box for stretches that range from two months to

five years, with nothing but a cot and a cold-water tap. Since two-

thirds of state prisoners come from the five boroughs, most of

them will come home to the city-and many will be mad, bitter

and confused when they are released.

Although there's no sure way to link later crimes with an

inmate's prison experience, a growing number of psychiatrists and

corrections experts say that intense and lengthy periods of isola-

tion of prisoners can prove volatile for inmates already on the

edge. Someday, they say, these men and women must return to the

streets-and communities will have to cope with the results.

"Severe perceptual deprivation continued for a period of time

has a toxic effect on the brain," says Dr. Stuart Grassian of

Harvard Medical School, who has published his research on the

effects of isolation in The American Journal of Psychiatry. "I

don't think people recognize the tremendous danger this poses for