Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Back To The Future Marxism and Urban Politics

Caricato da

Gustavo Jiménez BarbozaDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Back To The Future Marxism and Urban Politics

Caricato da

Gustavo Jiménez BarbozaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

CHAPTER FIVE

Back to the Future: Marxism and Urban Politics1

Jonathan S. Davies

Network theories of urban politics, such as urban regime theory, prospered greatly amidst the painful crisis of Marxism. Their central premise is that power is dispersed and hence that the task of governing is to mobilise and coordinate power to, the capacity to act. This perspective has become a powerful orthodoxy in political science, largely displacing Marxist theory. It is argued in this chapter, however that Marxism is essential to understanding contemporary urban politics. Its premise is that those who regret the passing of Marxism are excessively pessimistic, while those who acclaim the universal and eternal triumph of capitalism (or did so before the present crisis) are guilty of hubris or myopia. The chapter first explores the rise of the network orthodoxy. It proceeds to develop a critique of the regime-theoretical conception of the ruling class, building on my earlier work (Davies, 2002) and arguing that the Marxist conception is both stronger and, in the context of a theory of systemic power, more dynamic. It next examines the position of the urban proletariat, largely ignored by regime theory, arguing that the basic class structure of society depicted by Marx remains intact and consequently that working-class led transformations remain possible. It then moves from the macro to the micro level of analysis, illustrating the importance of class for understanding the dysfunctional dynamics of networked urban governance in the UK. It then demonstrates how the approach can be applied comparatively in explaining similarities and differences between two different forms of networked governance, UK partnerships and US

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1934157

regimes. In conclusion, it is argued that a new wave of Marxist research in urban politics is long overdue. The network orthodoxy Merrifield (2002: 129) suggests that the glorious ruin of the Marxist tradition is reflected nowhere better than in the intellectual journey of Manuel Castells from Marxist author of The Urban Question (Castells, 1977) to apologist for capitalist globalization, dazzled by the dynamism of Silicon Valley (Merrifield, 2002: 132). So inspired, Castells (1996) proclaimed the network society, a world in which hierarchy is increasingly superseded by heterarchy with power dispersed among autonomous centres caught up in a web of mutual dependence, resulting in interdependence rather than domination (Callinicos, 2001: 36). Castells may have little immediate influence in contemporary urban politics, but his intellectual trajectory symbolized the oft-travelled journey from capital and class to dispersal and difference. Clarence Stone developed an intellectual archetype for network analysis in the form of urban regime theory, whose influence extends far beyond the US. A regime is an informal yet relatively stable group with access to institutional resources that enable it to have a sustained role in making governing decisions (original emphasis, Stone, 1989: 4). It is the informal arrangements by which public bodies and private interests function together in order to be able to make and carry out governing decisions (1989: 6). Regime theory has become an orthodoxy in urban politics over the past 20 years. It has been robustly criticized and defended in that time but merits further attention. This is partly because it is orthodoxy with a critical edge, contending, unlike postmodern network theories, with the problem of inequality from the standpoint of

Page 1 of 24

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1934157

political economy, and partly because it was founded on the critique of Marxism (see Imbroscio, this volume). Regime theory and the ruling class The regime-theoretical break with Marxism was neither clear, nor complete. Early on, Stephen Elkin cautioned that intellectual ruin would follow, if urbanists did not maintain a sense of the larger political economy and Marxism (1979: 23). Stones conception of systemic power is pivotal to regime theory. Systemic power is: that dimension of power in which durable features of the socioeconomic system (the situational element) confer advantages and disadvantages on groups (the intergroup element) in ways predisposing public officials to favour some interests at the expense of others (the indirect element) ... Because its operation is completely impersonal and deeply embedded in the social structure, this form of power can appropriately be termed systemic (Stone, 1980: 980/1). For Stone, systemic power generates an indirect conflict between favoured and disfavoured groups, predicated on a schematic distinction between public and private power. The ownership of productive assets rests in the hands of business, while the machinery of government is subject to popular control through elections and other public inputs (Elkin, 1987: 18; Stone, 1989: 9). However, business control over production tends to give it a privileged voice in urban policy (Stone, 1980: 982). Urban regimes are founded on the need for city governments to secure the consent of corporations to the levy of taxes and bonds, which they will agree only if they favour the planning and development policies of the authority in question. These fiscal strictures create an environment where businesses and city government recognize congruent Page 2 of 24

interests and negotiate around them. Regime theory therefore accepts Lindbloms (1977) proposition that in market societies, governments are pre-disposed to indulge the preferences of business leaders. This is a theory of class power, but one that rejects the Marxist conception of the ruling class. Stones class imprint comes about contingently and in ways requiring no ruling elite or command forms of domination (1980: 979), notions he considers central to Marxism. He sees society as loosely co-ordinated and rejects the economy-centred view characteristic of Marxism (Stone, 1989: 226-227). Stone contends (1980: 985) that business interests prevail not because a ruling-class network promotes pro-business proposals, but because governments are drawn by the nature of underlying economic and revenue-producing conditions to serve those interests. Business influence is therefore greater in a policy area like urban renewal that is related to revenue production than in an area like governmental reform that is unrelated to revenue production.

Thus depicted, Marxism conceives the ruling class as a cohesive elite capable of identifying decisions crucial to its interests and acting to realise them. However, the classical Marxist approach is actually closer to the formulation of systemic power outlined by Stone than to any vulgar conception of a monistic and comprehensively rational ruling class. Callinicos rejects the canard thus: only in the most vulgar leftist (or in fascist) critiques do a handful of monopolists get to pull the strings. Capitalist firms are necessarily involved in a structure of conflictual interdependence that they cannot individually or even collectively dominate (2001:

Page 3 of 24

37). The structure of capitalist competition makes capitalists a band of warring brothers, rendering control always partial and occasionally precarious. Read as the self-conscious action of comprehensively rational elites, class domination is indeed implausible. However, the struggle among capitals does not mean that a ruling class is unable to dominate society. Like regime theory, Marxism draws on an impersonal conception of systemic power. Just as Stones conception leads city officials to understand as a matter of common sense that they must cooperate with business interests, so Marxs analysis of capitalism predicts a tendency among ruling and working classes alike to behave in ways which favour competition, accumulation and expropriation until periods of crisis undermine these routines and, for the working class in particular, opens them to question (Davies, 2002: 12). This approach demands no conspiracy. However, it differs from regime theory in one crucial detail: prevailing commonsense is not sufficient to explain class behaviour. For Marxists, systemic power is embodied in the day-to-day workings of capitalism, which cannot but produce frantic competition, socioeconomic polarization and economic crises, processes that are nurtured, managed and regulated by the capitalist state. Notwithstanding the imperative for political parties to win elections, states and capitals are structurally entwined. The relationship is best characterized as one of dialectical interdependence (Ashman and Callinicos, 2006), where each party has distinct, but closely related, interests. Governmental success in pursuing any agenda ultimately depends upon the size and profitability of the capitals based in their territory. This fact endows states with a positive interest in promoting the process of capital accumulation within their borders and makes them liable, should they be perceived to be pursuing policies inimical to this process, to the negative sanctions of capital flight, currency and debt crises and the like (Ashman and Page 4 of 24

Callinicos, 2006: 114). At the same time, successful capital accumulation depends on states developing a pro-business environment, labour supply and markets. Capital may have partially decoupled from individual states but capital investment patterns show that it remains tied to geopolitical regions (2006: 125-6). Structural interdependence does not therefore reduce the interests of the state to those of fractions of capital, or even capital in its totality. The capitalist is principally concerned with maintaining and expanding capital, the state manager with territorial competition, intra-state competition and citizen consent. However, pursuing these distinct but overlapping goals makes the two forms of power congruent, while the modalities of the relationship vary significantly as capitalism develops (2006: 114) across time and space. Hence, in determining economic policy, government officials respond to territorial imperatives, as they perceive them, rather than directly to orders from a capitalist elite. The structural conflict among capitals would preclude any other course, even if territorial interests were immediately reducible to economic ones. Economic trends invariably require interpretation, meaning that state managers choose from a repertoire of policies seeking to align territorial and economic imperatives, often imperfectly and in the face of systemic crisis tendencies. Stone (1980: 989) concedes that unlike Marxists, he is not concerned with how specific constellations of systemic power come into being, but rather how the system of urban governance reproduces them. As Imbroscio (1998a,b) argues this leaves it with a static conception of the relationship between public and private power, which underpins Stones theory of stratification. Stone wrote in 1980, that public officials understand instinctively that their careers are well-served by enacting pro-business policy. However, his inattention to the Page 5 of 24

production and reproduction of systemic power leaves him unable to explain these instincts fully. Recognizing the dynamic structural interdependence of territorial and economic power in the context of ever-intensifying competition between cities and states is one way of overcoming this elision. Harveys (2005) discussion of the pro-capitalist kulturkampf during the 1970s illustrates this structural interdependence, of which the fiscal crisis in New York was emblematic. Over several years, the city accumulated significant debts, tolerated by creditors. In 1975, however, a powerful cabal of investment bankers refused to roll over the debt and pushed the city into technical bankruptcy (Harvey, 2005: 45). Under the ensuing regime, governing priorities were reversed. City revenues were used to pay debts to bond-holders requiring wage freezes, cuts in employment and social provision and the imposition of regressive user fees. Humiliatingly, municipal unions were required to invest their pension funds in city bonds, creating a structural incentive to moderation. The state was central to this process. William Simon, Secretary of the US Treasury, said that the terms of any bailout should be so punitive, the overall experience so painful, that no city, no political subdivision would ever be tempted to go down the same road (Harvey, 2005: 46). Harvey argues that this strategy was every bit as effective as the military coup in Chile, redistributing wealth to the upper classes in the midst of a fiscal crisis (2005: 45). A static analysis of the division of labour between state and market does not suffice to explain this coup for capital; the notion of structural interdependence is more illuminating. Capital acted to sustain itself in the face of the crisis of profitability and increasing competition. It was encouraged by a cash-strapped state machine faced with growing resistance at home and impending military defeat overseas. When Mayor Abraham Beame vacillated in the face of the Page 6 of 24

fiscal crisis, he was marginalized.

The governor of New York, Hugh Carey, created the

Municipal Assistance Corporation to manage the crisis, appointing Democrat financier Felix Rohatyn to chair it and lead the rescue effort (Lankevich, 1998: 216-222). According to Berman (2007), Rohatyn later conceded we have balanced the budget on the backs of the poor. This outcome, engineered jointly by state and capital, fundamentally changed the political landscape. It led liberal New Yorkers reluctantly to concede new realities and created the conditions in which the neoliberal commonsense of the feasible and desirable became hegemonic (Bourdieu, 1984, 1990). Local state actors who disputed the restructuring were coerced into compliance (e.g. Beame), removed or gradually socialized into pragmatic pro-market dispositions. Although neoliberalization occurred in different forms at different speeds and is by no means the universal governing rationality, depending among other things on local history and levels of resistance (Geddes, 2005), this analysis works on a wider canvas. Peck and Tickell (2002: 397-8) argue that neoliberalization has led to fast policy transfer, where ideas from America spread to Europe, and domestic urban policy processes were curtailed in favour of off the shelf solutions from elsewhere, leading to a deepening and intensification of neoliberalization, not least in the practices of city leaders and managers around the world. This conjuncture has made building progressive urban regimes in the USA virtually impossible, as Stone (1993) acknowledged. His optimism that they might be feasible lies his conception of stratification and the loosely coupled structures of society, which mean that some areas of governance are more or less removed from corporate influence. However, there is good reason to question Stones depiction of loose coupling, or low social coherence. The matter deserves far greater attention than it gets here, but stratification theory would suggest a lower Page 7 of 24

correlation between policy intentions and outcomes in different fields than appears to be the case. Stone (1998) sees education policy as a field with some potential. However, he offers

little evidence of progress apart from the formation of human capital coalitions, which are, in reality, instances of supply-side neoliberalism (Davies, 2004a). Many spheres of urban policy are characterised by this adaptive conformity to the imperatives of profit and competition. In addition, inequality has grown across the cities of the world, not only in relation to income and education but also across an array of indices covering many policy fields. In the political field too, the language of social critique has been appropriated to neoliberal discourse (Fairclough, 2000). The reform of public administration has encouraged homogenization. The attack on the professions, the rise of general management and the

imperatives of joined-up government have disciplined public officials with any semblance of radicalism and remade their sense of what constitutes good governance along neoliberal lines. The process has not been wholly successful (e.g. Hood, 2000), but the prospects for equitable regime politics appear considerably worse than in 1993. Harvey (2006: 82) argues that almost everything we now eat and drink, wear and use, listen to and hear, watch and learn comes to us in commodity form and is shaped by divisions of labor, the pursuit of product niches and general evolution of discourses and ideologies that embody precepts of capitalism. These developments indicate frighteningly high social coherence and suggest that Stone overemphasizes heterogeneity. The influence of capital, aggressively promoted by entrepreneurial states with territorial ambitions, extends into every interstice of society. At the same time, it is clear that the growth imperative does not have to be proselytized by a capitalist elite for different components of the state to take it seriously.

Page 8 of 24

As I suggested in my original critique (Davies, 2002), regime theory is thus unable to show, as Elkin put it (1987: 17), that a regime dedicated to both popular control and a property based market system can thrive. Despite favouring the commercial republic, Elkin recognized that the very workings of the political economy (1987: 181) thwart egalitarian aspirations. The notion of structural interdependence, the differential unity of territorial and economic interests within the capitalist system, offers a more convincing explanation for this reality than Stones conception of systemic power. Thus, regime theory has always been looking over its shoulder at the specter of Marx (Derrida, 1994). It should now turn and face it. The urban proletariat However, it is not sufficient to argue that Marxism has a superior account of state-capital relations than regime theory. Nor is it sufficient simply to argue that the dynamics of market economies make sustainable egalitarian regimes improbable. Taking egalitarian urban politics seriously demands that a source of political agency be identified that is capable of breaking the conjuncture. Marxist theory accords the leading role to the working class, those who live so long as they find work, and who find work only so long as their labor increases capital (Engels in Merrifield, 2002: 35). Bringing the proletariat into the discussion takes us far beyond regime theory, but it is essential if we are to understand the scope and limits of the neoliberal conjuncture and the potential for resistance to it. Moreover, the concept of a ruling class inevitably draws attention to subordinate classes. What hope, then, might urban egalitarians invest in todays proletariat, so comprehensively dismissed by mainstream sociology (Giddens,

Page 9 of 24

1998; Beck, 2007)? Answering this question requires us to examine changing class structures in the cities of both the developing and developed worlds. Using Bolivia as his example, Geddes (2008) argues that Marxists should look to the global south for inspiration. He finds that under the leadership of Evo Morales, a precarious coalition of proletarians, including urban coal miners, peasants, rural coca growers and indigenous ethnic groups has given new impetus to the opposition to neo-liberalism. However, the emergence of the global south as the vanguard of resistance poses challenges to Marxism. Mike Daviss (2006) story of the planet of slums shows the inexorability of urbanization. We have witnessed the emergence of vast informal settlements across Africa, Asia and South America, now constituting 78% of the urban population in the least developed countries and totalling over one billion impoverished citizens globally (Geddes, 2008). In

pessimistic accounts, the slum-dwellers are outcasts; they are no longer Marxs reserve army of labour, but a vast underclass permanently marooned from the labour market and the working class. In the classic accounts by Engels in Manchester and Marx in Paris, the city maybe Hell but the proletariat is forged there. From this perspective, urbanization is the source of

revolutionary agency. The question posed by the planet of slums is whether it now has any such power. Recent research (e.g. Zeilig and Ceruti, 2007; Dunn, 2008) suggests that urbanization could be the source of new proletarian agency. African slums are heterogeneous, mixing

enclaves of wealth and extreme poverty. Soweto is the archetype, with formal and informal settlements existing cheek-by-jowl with wealthy gated communities. Zeilig and Ceruti argue that the class composition of Soweto is complicated. There is no simple distinction between the Page 10 of 24

formal working class and the dclass slum-dweller. On the contrary, he finds that 78.3% of Sowetan households contain formally employed, unemployed and self-employed family members. Rather than forming a new labour aristocracy, those in formal employment bear onerous duties of kinship. The situation in Soweto, Zeilig and Ceruti conclude, is fluid. This picture lends additional importance to the spate of trade union struggles in South Africa. In 2007, the country witnessed a public sector general strike, the largest of its kind since apartheid. If Zeilig and Ceruti are right, this was no last-gasp of a dying proletariat, but the harbinger of renewal. Moreover, if the picture of class composition and household interdependence is correct, workers and unemployed alike share a common interest in these struggles, with solidarity between them possible. Zeilig and Ceruti conclude that similar patterns of class composition and resistance are evident in many cities across the African continent (see also Zeilig, 2002). Dunn (2008) embellishes the point in his friendly critique of Harveys (2005, 2006) conception of accumulation by dispossession, the predatory commodification of the commons characteristic of neoliberalism. Accumulation by dispossession has occurred continuously since the first enclosures in England in the 15th Century. Today, Arundhati Roy describes the

garrotting of Indias rural economy through the privatization and transfer of public assets to corporations. The widespread privatization of the ejidos system of communal land ownership and farming in Mexico was a key factor driving millions from country to city in pursuit of a living. Here, urbanization is double-edged entailing not only migration from the country to the city, but also the urbanization of the rural through expropriation and the introduction of industrial production methods.

Page 11 of 24

Accumulation by dispossession is also happening on a massive scale in capitalist China (Liang et al, 2002). However, normal capital accumulation, the extraction of surplus value from labour, has also expanded (Dunn, 2008). If true and new processes of surplus value extraction routinely follow urbanization, then the structure of class relations identified by Marx remains intact and rising class militancy is possible. According to Dunn (2008: 24), this has occurred in China. Even official statistics suggested a ten-fold jump in the number of strikes and strikers between 1994 and 2003. Across Africa, China and Latin America, there is evidence that new class-based struggles follow urbanization. Mega cities are spaces of brute deprivation, but they are also spaces of hope where people contest the dynamics and outcomes of urbanization. Urbanization, informalization and class reformation have occurred throughout the history of capitalism. The difference today maybe simply the scale and speed of events, with co-dependent informal and formal working classes growing rapidly in parallel. These studies leave us with reason to be hopeful, at least, that class recomposition may occur alongside urbanization. If so, Marxist analyses of

developing cities will generate interesting insights into urban political economy and reveal the interstices at which capitalism and its ravages maybe confronted. Much hangs, therefore, on the class character of the new urban proletariat. The challenge to class in the developed world is the reverse. Where slum-dwellers are depicted as a vast underclass, the majority of the Western working class is depicted as exiting upwards, lifted by the tide of post-war prosperity. Together with changing structures of

economic production and competition, rising prosperity has lead to individualization, the rise of the me generation (Milburn, 2006). At the other end of the social hierarchy, however, New Page 12 of 24

Labours socially excluded are also depicted as dclass. They are an alienated underclass comprising some 3% of the population, marooned from mainstream society, and incapable of exercising moral agency without the cultural re-engineering characteristic of third-way social policy (Levitas, 1998). This anti-class narrative (e.g. Beck, 2007) has been particularly influential in Britain and the US, where combative class struggles are still rare. However, it is open to challenge

(Atkinson, 2007). For example, Zweig (2001) suggests that the people on the lowest rungs of society in the US are not concentrated in an underclass, but tend to move back and fore from badly paid employment to unemployment as a reserve army of labour. Other studies reject the dominant prosperity narrative, pointing out that over the lifecycle the majority suffer some form of insecurity and deprivation and, moreover, that in the heady days before the crisis, consumption was driven primarily by debt rather than affluence (Crouch, 2008). At the other end of the social scale, massive and increasing amounts of power and wealth are concentrated in the hands of a tiny super class (Byrne, 2005). Patterns of class polarization persist and intensify, as they do in developing cities. What Lasch (1995) calls the revolt of the elites is imprinted on cities from London and New York to Johannesburg and Caracas. In terms of working class organization, although way down from peak membership in the early 1980s, by historical standards a high proportion of the population in Britain remains unionised. The proportion of workers in full-time, permanent employment in the UK was still 81.7% in 1999, down only fractionally from 82.8% in 1984 (Smith, 2007). Despite the

neoliberal assault, most British people still self-identify themselves as working class (Mortimore, 2002). In Europe, militant class struggles occur frequently, notably in France, Greece and Italy. Page 13 of 24

Dunns (2004) comparative study of restructuring in four major industries concluded that some processes have fragmented the working class, while others have had a cohering effect. None, he concludes, makes the working class inherently less significant than it was in the halcyon days. The point is not to paint a rosy picture of class struggle. It is rather to suggest that those who proclaim the end of class lack perspective, confusing conjunctural change with epochal change. Certainly, they are foolish to dismiss Marxism tout court. Perhaps, then, the mushrooming global-local working class has the potential to struggle for equality, to which regime theorists and other proponents of network governance vainly aspire through collaborative politics. However, it is also pertinent to ask what, if anything, Marxism can contribute to our understanding of the institutionalized form of network governance, proliferating across much of the world. In a premature obituary to Marxism, Storper claims that it only ever offered macro level descriptions and said nothing about the micro-foundations of society (2001: 158). The following discussion refutes this critique, showing how Marxist

analysis illuminates the deflected class politics of networked governance in the UK and developing a platform for the comparison of distinct network forms, such as US regimes and UK partnerships. Networked governance, class politics and hegemony in the UK In the UK, the neoliberal turn began in the mid 1970s with public spending and real wage cuts following the IMFs New York-style bailout of the national economy. Margaret Thatchers Conservatives replaced the discredited Labour government in 1979. Thatchers goal was to restore the national enterprise culture destroyed, she claimed, by the social democratic welfare state (Gamble, 1994: 167). To achieve it, Britain needed purging of social democracy (ibid: Page 14 of 24

220). To this end, Thatcher engineered successful confrontations with key trade unions, notably the 1984-5 coal miners strike. In individualization theory, this was the last hurrah of a trade union movement fatally weakened by changes in the social base during the post-war period. For Marxists, the defeat had different connotations associated with the dominance of pro-Labour reformism in the working class and the cooption of militant shop stewards into well-paid fulltime union positions. In Marxist analysis, the trade union bureaucracy is a privileged,

tendentially conservative stratum, which played an important role in sapping the militancy of the movement when Labour was in power and in the ensuing confrontation with the Tories. Defeat was thus contingent, but its effects were devastating. Organized labour, the left in the Labour Party and local authorities abandoned confrontation and gradually conceded to the new pragmatics of neoliberalism. Expectations of class militancy evaporated among demoralized socialists (Gough, 2002: 418), to be superseded by a new realism (Hay, 1999: 1). The new realism entailed, among other things, willingness among former militants to collaborate with representatives of the state and capital in new urban partnerships, in pursuit of scarce resources. Many citizen-activists in todays partnerships share painful memories of political defeat and marginalization during the 1980s and see the partnership big tent, for all its flaws, as progressive. Over time, through habituation and as old practices faded from memory, what was first a painful necessity became, for many, a virtue reflected in the prevalent dispositions of those now sharing an ideological commitment to collaborative network governance (see Davies, 2004b: 576-7). This partnership ethos, or logic of partnership (Davies, 2009a) arose from the structural and contingent conditions leading to the defeat of the working class in the 1980s and the contingent political effects of that defeat. The idea of partnership became part of the

commonsense of many on the moderate left in the UK and, as a motherhood and apple pie Page 15 of 24

concept, influenced citizen activists who might previously have looked to struggle for solutions (Davies, 2009a). Influenced by the US, the Thatcher and Major governments introduced urban policy programmes promoting collaboration between business and local government. When New Labour came to power in 1997, the notion of partnership fitted its interpretation of the conjuncture. The demise of class solidarity, the imperatives of national economic

competitiveness, the associated need to re-mobilize the citizenry and the need to offer an inclusive vision of society made partnership the commonsense approach. Since 1997, partnership institutions have penetrated every sphere of local government. The discourse and practice of partnership is hegemonic to a degree that it probably would not be if not for the gravity of the class defeats of the 1980s and New Labours adaptation to them. City strategic partnerships are a prominent example. Comprising state, market and third sector actors, they are supposed to tap into supposedly diverse centres of power not through hierarchy, but negotiation, diplomacy and building trust. Importantly, they seek to include citizen activists as part of the governing effort. In these ways, partnerships are supposed to eliminate nugatory effort, generate capacity, or power to and enhance joined-up government (Davies, 2009a). Yet, despite dominating the local political landscape, partnerships are frequently dysfunctional. Far from facilitating political agreement between actors with congruent interests, political debate and dissent are taboo. Community activists are sometimes captured or coopted but they are often angry and bitter about their treatment at the hands of state managers (Perrons and Skyer, 2003). Dissenters are branded troublemakers and marginalized (Davies,

2007). This neoliberal mode of governing, characterized by the eviction of politics from policy, has been called technocratic managerialism (Skelcher et al, 2005). Page 16 of 24

How, then, can we explain this juxtaposition of the politics and ethos of partnership on the one hand with conflict, citizen marginalization and governmental control freakery on the other? The essence of the explanation is that the technocratic managerialism characteristic of contemporary governance is a dynamic outgrowth of contradictions within neoliberalism. It hinges on the idea that neoliberalism is the unintended, unavoidable and unstable synthesis of liberalism and authoritarianism (Jessop, 2002; Harvey, 2005; Davies, 2009b). There are three reasons for this synthesis. First, liberalizing governments confront the continuing legacy of postwar welfarism embedded in the public and professional consciousness despite the 30-year long neoliberal assault (e.g. Park et al, 2003). Technocratic managerialism is one response to this challenge. Second, neoliberal doctrine demands the extraction of greater value from the public pound by raising productivity and cutting costs, placing downward pressure on expenditure and requiring the rigorous performance management of public services. Thirdly, however, state

managers have to manage the polarizing effects of liberalization, marked, for example, by everincreasing inequality and concomitant upward pressure on public expenditure (e.g. Dorling et al, 2007). The rollback of the welfare state fractured and damaged societies, requiring more or less coercive and costly supervision of working class losers. Each of these factors predicts centralization. The neoliberal state has violated the tenets of free market orthodoxy by investing in coercive mechanisms and unifying moral doctrines of community and active citizenship. In the US, this mix is called neo-conservatism. In the UK, New Labour appeals to individual responsibility, family, community and nation, producing a deep substratum of coerced co-operations and collaborations (Harvey, 2000: 181). Thus, neoliberalism denies the very freedoms that it is supposed to uphold (Harvey, 2005: 69). Centralization, so understood, is dynamic. The social dislocation caused by neoliberalizaiton, Page 17 of 24

combined with the intensification of competition between structurally interdependent territories and capitals, creates intense demands within the state for constant change, innovation and improvement alongside attempts to clamp down on costs. Centralization is the unwanted but indispensable governmental response to social instability unleashed by deregulation, the extension of the market realm, rising inequality and the consequent decline of the public (Marquand, 2004). In addition, the current accumulation crisis has forced states to invest

trillions of dollars of public money to save capitalism from catastrophe. This analysis adds a dynamic quality to the concept of systemic power developed by Stone. It is the evolving and contested relationship between state, capital and class, with

different articulations in different governing systems, localities and temporalities. In the 1970s capital became the leading face of systemic power in crushing the social democratic order. However, the strong state always remained a key term; it has gradually become more prominent and is arguably, for now, the leading face of systemic power. The state was always coming back in long before the crisis and notwithstanding the post-national rhetoric of globalization theory. Urban partnerships are a micro-case of these dynamics in practice. As state managers grapple with more or less overt non-compliance and dissent by working class interlocutors, they resort increasingly to coercive and exclusionary tactics. This outcome is a partial failure of hegemony. New Labour has sought to generate a new gemeinschaft, where all segments of society know instinctively how to behave in a variety of situations and citizens are at ease with the rigours of risk and competition and reinvent themselves by responding reflexively to market demands for new skills. There is a fine line between encouraging active citizenship and ensuring that it does not tip over into dissent and the Page 18 of 24

demand for new rights. Mobilizing citizens in a capricious world therefore requires a robust hegemonic strategy and partnership is a key institutional mechanism for New Labours hegemonic project. It is corporatism without unions where working class actors, otherwise written out of history, reappear in the guise of dclass community representatives. It serves a hegemonic function in that when community representatives commit themselves to the idea and practice of collaboration, doing so entails the recognition of state and market interlocutors as partners and effectively concedes the right to organize as dissenters against them. Persuasion becomes the only acceptable mode of contention (Davies, 2007: 794). Yet, class remains indelibly imprinted on the partnership form. My recent study of collaborative governance (Davies, 2007) revealed creeping managerialism where local state managers, under pressure from higher tiers of government, sought to structure out dissent and debate so that the partnerships could focus more effectively on delivering public service targets. Community activists and public managers drew on competing values when defining the purpose of partnership, centred respectively on rights (to a voice) and responsibilities (to contribute to the governing effort). However, these value conflicts were sublimated and closed to conscious deliberation in the partnership arena. To explain this puzzle I turned to Bourdieus concept of habitus, which describes how tacit knowledge develops and cultural and linguistic resources arise from and help to sustain class power (Bourdieu, 1990: 9). State managers and community activists drew on their distinctive habitus in interpreting the partnership environment, meaning that in a context where conflict is taboo, they could not understand each other despite sharing a common vocabulary. These unspoken class conflicts undermined collaboration, prompting

public officials to reform structures in a way that further marginalized and antagonized dissenters. Page 19 of 24

Partnership is, by definition, not an arena of open class struggle. Engels described petty crime, or privatized redistribution, as the crudest and least fruitful form of rebellion (Merrifield, 2002: 40). Tacit and passive class resistance in partnership is probably the second least fruitful. Yet, it signals a partial failure of hegemony. Partnership maybe an effective mechanism for damping down open class conflict, but it has been far less effective in creating cross-class alliances and managing the antinomies of neoliberalism. Unless the working class adapts

spontaneously to the vicissitudes of a neoliberal society, or makes a decisive move against it, further marketization is likely to lead to further socioeconomic instability and further dissent, followed by further centralization. This is New Labours dialectical bind (Davies, 2005: 327). Towards comparative Marxist analysis This analysis can be applied cross-nationally, providing the basis for a comparative reading of the different forms taken, for example, by UK partnerships and US regimes. It should be clear from the foregoing discussion that both mechanisms reflect decisive shifts in the statecapital-class conjuncture arising from accumulation crises and the subsequent effort by states to resolve them by crushing labour and socialist movements. However, historically and culturally divergent national and local state systems mediate this common context. Diverse institutions appear within a spatially differentiated neoliberal conjuncture, pursuant to varying political goals. The archetypal US business regime operates through state managers working informally with business elites, while excluding working class representatives. The UK city strategic partnership seeks to mobilize governing resources by coPage 20 of 24

opting working class citizen-activists in a context where direct business involvement is, typically, tokenistic. Put simply, the regime pursues growth, the partnership hegemony. Conclusion The chapter makes four substantive points. First, it argues that the Marxist conception of systemic power is stronger and more flexible than that of regime theory. Highlighting the dynamic and evolving relationship between state, capital and class adds value both to regime theory and the analysis of collaborative urban governance in the UK. The US-UK comparison shows that Marxist analysis can explain a variety of political formations. At the same time, it demonstrates that the Marxist conception of the ruling class requires no immediate involvement in or command of governing institutions by corporate elites. As Geddes (2008) argues, Marxism highlights both the diversity of global neoliberalisms and the universal features of neoliberal urban space. Contra Storper (2001), it offers an insightful synthesis of the universal and the particular. Second, the discussion of UK urban partnerships demonstrates the impact of class at the micro-level. Marxist analysis casts light on the class politics of individual partnerships and, at the same time, shows how they contribute to explaining changes in the contemporary form of systemic power, where the strong state was advancing in defence of the so-called free market long before the crisis made this relationship transparent. The discussion thus moves from a dynamic analysis of systemic power to a dynamic conception of the micro-politics of networked governance and back. Third, the analysis reinforces my earlier point (Davies, 2002) that the empirics of regime theory do not support its normative project of egalitarian regime building. It suggests in addition Page 21 of 24

that Stones conception of social stratification exaggerates policy diversity and underplays the extent to which the structural interdependence of states and markets creates trends towards policy homogeneity. Marxist analysis can correct this elision without resorting to reductionism or determinism, by focusing on how neoliberalization occurs and is resisted, in different policy spheres. Fourth, while regime theory has had plenty to say about class structure it overlooks the working class. This is an important gap because the proletariat has been central to all the great urban-led transformations of the past 150 years. The rebellion against Ceausescu in Timisoara heralded the fall of the Eastern Bloc. The Paris Commune has inspired the left for generations, as has revolutionary Barcelona. Class struggle in Soweto was pivotal to the defeat of apartheid in South Africa. If the contemporary proletariat retains its structural integrity, as argued here, then class struggle will be central to urban transformations of the future. As Harvey argues the mass of the population has either to resign itself to the historical and geographical trajectory defined by overwhelming class power or respond to it in class terms (cited in Dunn, 2008: 24). This analysis does not chime with the prevalent commonsense. However, the notion of common sense merely signals the uncritical absorption of dominant ideas. Critical sense, on the other hand, lends us a sense of incredulity towards the desirability and sustainability of current social relations, and is oriented towards transformation (Harvey, 2006: 85-6). This should be the disposition of our sub-field. Marxist analysis can rectify deficits in regime theory, without contradicting Stones adage local politics matters. Yet, it too must be open to critique. It must be open and reflexive, sensitive to changes in the state-capital-class conjuncture (Harvey, 2006: Page 22 of 24

78-9). The state of the city and the world means that a renaissance in Marxist scholarship of this kind is an urgent priority. _____________________

This chapter draws on research entitled Interpreting the Local Politics of Social Inclusion

funded by the ESRC (award RES-000-22-0542). Many thanks to David Imbroscio and Mike Geddes for insightful comments on earlier drafts.

Page 23 of 24

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Cervero 2002Documento8 pagineCervero 2002Gustavo Jiménez BarbozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Padrilla Cobos - Ciudades Compactas, Dispersas, FragmentadasDocumento3 paginePadrilla Cobos - Ciudades Compactas, Dispersas, FragmentadasGustavo Jiménez BarbozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Making The ConnectionsDocumento145 pagineMaking The ConnectionsGustavo Jiménez BarbozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sheller, M. - MobilityDocumento12 pagineSheller, M. - MobilityGustavo Jiménez BarbozaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Summary of Some Characteristics of The Gated Communities in The Great Hungarian PlainDocumento5 pagineThe Summary of Some Characteristics of The Gated Communities in The Great Hungarian PlainGustavo Jiménez BarbozaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- An Effect On Charles Dickens FianlDocumento16 pagineAn Effect On Charles Dickens Fianlapi-312061708Nessuna valutazione finora

- Role of Microfinance in Odisha Marine FisheriesDocumento8 pagineRole of Microfinance in Odisha Marine FisheriesarcherselevatorsNessuna valutazione finora

- Sociology 3 Module 1-2 Amity UniversityDocumento25 pagineSociology 3 Module 1-2 Amity UniversityAnushka SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Combatting Child Labor Project Terminal Narrative Reports Nov 2012 Dec 2015 KKSDocumento15 pagineCombatting Child Labor Project Terminal Narrative Reports Nov 2012 Dec 2015 KKSBar2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Urban Youth Centre Setup GuideDocumento53 pagineUrban Youth Centre Setup GuideAnjo AglugubNessuna valutazione finora

- Children in Polyamorous Families: A First Empirical LookDocumento94 pagineChildren in Polyamorous Families: A First Empirical LookDiana Matilda CrișanNessuna valutazione finora

- BIHAR in 21st Century: Challenges and OpportunitiesDocumento10 pagineBIHAR in 21st Century: Challenges and OpportunitiesMaaz AliNessuna valutazione finora

- March 12, 2012 IssueDocumento8 pagineMarch 12, 2012 IssueThe Brown Daily HeraldNessuna valutazione finora

- The Disability ModelDocumento20 pagineThe Disability ModelLouise GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Long Time Ago A Remote VillageDocumento4 pagineLong Time Ago A Remote Villagepuz00Nessuna valutazione finora

- 02 Eye For OrderDocumento100 pagine02 Eye For OrderUsman Aliyu100% (1)

- Cole GDH - A History of Socialist Thought Vol 1Documento363 pagineCole GDH - A History of Socialist Thought Vol 1marcbonnemainsNessuna valutazione finora

- (1961) Andrew Gunder Frank. The Cuban Revolution. Some Whys and Wherefores (The Economic Weekly)Documento12 pagine(1961) Andrew Gunder Frank. The Cuban Revolution. Some Whys and Wherefores (The Economic Weekly)Archivo André Gunder Frank [1929-2005]Nessuna valutazione finora

- Good Food For All Agenda 2017Documento48 pagineGood Food For All Agenda 2017LA Food Policy CouncilNessuna valutazione finora

- PGDBA 2019 (English)Documento30 paginePGDBA 2019 (English)Hemang PatelNessuna valutazione finora

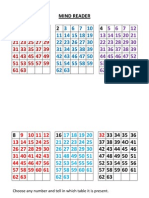

- PuzzleDocumento11 paginePuzzleVolety Sai SudheerNessuna valutazione finora

- 196, DT 10 05 2013-ESW-LIGDocumento3 pagine196, DT 10 05 2013-ESW-LIGbharatchhayaNessuna valutazione finora

- tmp8F67 TMPDocumento106 paginetmp8F67 TMPFrontiersNessuna valutazione finora

- Punjab EconomicSurvey2017-18 PDFDocumento323 paginePunjab EconomicSurvey2017-18 PDFSuresh KakkarNessuna valutazione finora

- Tanzania 5 Year Development PlanDocumento193 pagineTanzania 5 Year Development PlanRussell Osi100% (1)

- SGBS Trust UnnatiDocumento4 pagineSGBS Trust UnnatiManisha JoshiNessuna valutazione finora

- Key Concept SynthesisDocumento2 pagineKey Concept SynthesisscribdNessuna valutazione finora

- Wa0007Documento4 pagineWa0007Kritiraj KalitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Preferential Option For The PoorDocumento14 paginePreferential Option For The Poorrhann17Nessuna valutazione finora

- Management ThesisDocumento57 pagineManagement Thesisvibhav29100% (16)

- Voluntary Welfare MeasuresDocumento8 pagineVoluntary Welfare MeasuresAnil Gangar100% (2)

- Social Status and Class in The Great GatsbyDocumento1 paginaSocial Status and Class in The Great GatsbySally GuanNessuna valutazione finora

- Nbo - National Buildings OrganisationDocumento11 pagineNbo - National Buildings OrganisationRanjith KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Welfare Handbook: Demographics, Education, EmploymentDocumento472 pagineSocial Welfare Handbook: Demographics, Education, EmploymentAkshay ThakurNessuna valutazione finora

- Democracy in Black: How Race Still Governs The American Soul Black - Excerpt FinalDocumento2 pagineDemocracy in Black: How Race Still Governs The American Soul Black - Excerpt Finalwamu885100% (1)