Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Justice Neri Final

Caricato da

Ernesto Baconga NeriDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Justice Neri Final

Caricato da

Ernesto Baconga NeriCopyright:

Formati disponibili

SECOND DIVISION

LADISLAO ESPINOSA, Petitioner,

G.R. No. 181071 Present: CARPIO, J., Chairperson, BRION, DEL CASTILLO, ABAD, and PEREZ, JJ. Promulgated: October 17, 2011

-versus-

PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Respondent.

x------------------------- -----------------------------x

RESOLUTION

NERI, J.:

We grant Ladislao Espinosas (Espinosa) motion for reconsideration of this Courts Decision of 15 March 2010 (Decision).

The assailed Decision affirmed the Court of Appeals, dated 25 September 2007, in CA-G.R. CR No. 29633. The Decision did not consider Espinosas invocation of complete self-defense as provided for in Article 11 (1) of the Revised Penal Code.

In support of his motion for reconsideration, Espinosa submits new evidences.

1. An ice peak was pointed at Espinosa just before the stone was thrown at him. 2. Merto was only disarmed after Espinosa was restrained by his cousin, Rodolfo Muya.

This evidence is in addition to the undisputed facts of the case, as found by the Regional Trial Court, and as confirmed by the Court of Appeals on appeal. It may be so summarized:

On 6 August 2000, at about 10 oclock in the evening, private complainant Andy Merto, bearing a grudge against the petitioner, went to the house of the latter in the Municipality of Sta. Cruz, Zambales. While standing outside the house, private complainant Merto shouted violent threats, challenging the petitioner to face him outside.

Sensing the private complainants agitated state and fearing for the safety of his family, petitioner went out of his house to reason with and pacify Merto. However, as soon as he drew near the private complainant, the latter hurled a stone at the petitioner. The petitioner was able to duck just in time to avoid getting hit and instinctively retaliated by hitting the left leg of the private complainant with a bolo scabbard. The private complainant fell to the ground. Petitioner then continuously mauled the private complainant with a bolo scabbard, until the latters cousin, Rodolfo Muya, restrained him.

As a consequence of the incident, private complainant Merto sustained two (2) bone fractures, one in his left leg and another in his left wrist. It took about six (6) months for these injuries to completely heal.

The Issue

The sole issue raised in this appeal is whether under the set of facts given in this case, complete self-defense may be appreciated in favor of the petitioner.

The Ruling of the Court

In consideration of the new evidences presented, this court holds that all elements of self-defense are present in this case.

The Revised Penal Code provides the requirement of self-defense as a justifying circumstance, to wit:

Article 11. Justifying circumstances. The following do not incur any criminal liability:

1. Anyone who acts in defense of his person or rights, provided that the following requisites concur:

First. Unlawful aggression; Second. Reasonable necessity of the means employed to prevent or repel it; Third. Lack of sufficient provocation on the part of the person defending himself.

Unlawful aggression is equivalent to assault or at least threatened assault of an immediate and imminent kind.1 Unlawful aggression on the part of the private complainant Merto was present in this case. His action of pointing an ice peak and throwing a stone to the latter in a sudden and successive manner were enough to prompt the petitioner to take defensive action. Considering the danger posed by these objects and the manner it was used against the life and limb of the petitioner, the court takes this as a basis for self-defense.

There is lack of sufficient provocation in the part of the petitioner. It was the private complainant Merto, who in the fit of rage, called out the petitioner and invited him for a fight to satisfy the formers grudge.

With the presentation of the new evidences, the argumentation now lies on the existence of the second element which is the reasonable necessity of the means employed to prevent or repeal the attack. To wit:

The second requisite of defense means that (1) there be a necessity of the course of action taken by the person making a defense, and (2) there be a necessity of the means used. Both must be reasonable. The reasonableness of either or both such necessity depends on the existence of unlawful aggression and upon the nature and extent of the aggression.2

The necessity of the course of action taken by the petitioner of attempting to incapacitate and disarm the private complainant arose from the threat posed by the latters action of throwing a rock and pointing an ice peak towards petitioner. The petitioner used the only tool available for defense at his immediate disposal the bolo scabbard. He mauled the private complainant until the aggression ceased only

1

People vs. Alconga, 78 Phil. 366 REYES, The Revised Penal Code, 2006 Edition, p 173

by the intervention of a third person. The defense was necessary as well as the means used by petitioner to defend his life. For both conditions to meet this second element of self-defense, necessity should not only be present, they should also be reasonable.

The measure of reasonableness of the action taken is provided for in the doctrine of rational equivalence, delineated in People v. Gutual,3 to wit:

x x x It is settled that reasonable necessity of the means employed does not imply material commensurability between the means of attack and defense. What the law requires is rational equivalence, in the consideration of which will enter the principal factors the emergency, the imminent danger to which the person attacked is exposed, and the instinct, more than the reason, that moves or impels the defense, and the proportionateness thereof does not depend upon the harm done, but rests upon the imminent danger of such injury.

The doctrine of rational equivalence presupposes the consideration not only of the nature and quality of the weapons used by the defender and the assailantbut of the totality of circumstances surrounding the defense vis--vis, the unlawful aggression.4 The private complainants sudden use of force by hurling a rock and pointing an ice peak before the petitioner triggered his instinct of self-preservation to take over his actions. The imminent danger posed by such threats did not afford the petitioner to discern what proper tool to use in able to defend himself. Instinct has instructed the petitioner to use the bolo scabbard he was holding at that time to unable the private complainant from consummating his malicious intention. He continued to maul until the intervention of a third party effectively disabled both of them. In those moments of defense, petitioner has no effective control over his senses. He had no knowledge of what degree of power he applied to consummate his defense. As a consequence, petitioner inflicted those injuries to the private complainant.

3

G.R. No. 115233. February 22, 1996 Espinosa v. People, G.R. No. 181071, March 15, 2010

A review of the facts shows that after petitioner was successful in taking down private complainant Merto. However, the threat to petitioners life has not ceased since the former still held the ice peak and was still capable of thrusting it into petitioners body. The aggressor was not neutralized; the aggression did not cease. This fact was clearly established by the new evidences presented. Clearly, the continuous hacking by the petitioner still falls within the ambit of self-defense thus justified. The aggression effectively stopped when Rodolfo Muya restrained the petitioner and disarmed Merto. By this time, petitioner has already inflicted injuries upon private complainant Merto in an act of self defense.

In the final analysis, all three elements of self-defense are present in this case. The argument on reasonable necessity of the means employed to repeal or prevent such aggression is found meritorious with the introduction of the new evidence. The law on self-defense embodied in any penal system in the civilized world finds justification in mans natural instinct to protect, repel, and save his person or rights from impending danger or peril; it is based on that impulse of self-preservation born to man and part of his nature as a human being.5

WHEREFORE, the instant appeal is GRANTED. The decision of Branch 71 of the Regional Trial Court of Iba, Zambalaes finding accused-appellant LADISLAO ESPINOSA, guilty beyond reasonable doubt of the crime of serious physical injuries is REVERSED and SET ASIDE and another is hereby entered ACQUITTING him of the charge. He should forthwith be released from detention, unless his further detention is warranted for any other legal or valid ground.

SO ORDERED.

5

Castanares vs CA, Nos. L 41269 70, August 6, 1979

ERNESTO BACONGA NERI Associate Justice

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Empowerment Ordinance 2 PDFDocumento7 pagineEmpowerment Ordinance 2 PDFErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Letter To Petals - SubsidyDocumento1 paginaLetter To Petals - SubsidyErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- City of Cagayan de Oro Oro Youth Center, 5 Floor JV Serina Building, City Hall Tel Nos (088) - 857-4281 Local 501Documento2 pagineCity of Cagayan de Oro Oro Youth Center, 5 Floor JV Serina Building, City Hall Tel Nos (088) - 857-4281 Local 501Ernesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Naga City Youth Code PDFDocumento16 pagineNaga City Youth Code PDFErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Letter To IndahagDocumento1 paginaLetter To IndahagErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Letter To Dean For Moot Court ReservtionDocumento1 paginaLetter To Dean For Moot Court ReservtionErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Education Health Security Environment Disaster Preparedness and Response Economic SecurityDocumento3 pagineEducation Health Security Environment Disaster Preparedness and Response Economic SecurityErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Torayno Vs ComelecDocumento10 pagineTorayno Vs ComelecErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Letter of ExcuseDocumento2 pagineLetter of ExcuseErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Proposed 2011 Xu Magna Carta of Students' Rights and Responsibilities For Undergraduate Students of Xavier University Ateneo de CagaynDocumento18 pagineProposed 2011 Xu Magna Carta of Students' Rights and Responsibilities For Undergraduate Students of Xavier University Ateneo de CagaynErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Draft Magna Carta of StudentsDocumento18 pagineDraft Magna Carta of StudentsErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Water FountainsDocumento4 pagineWater FountainsErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- New CSG Strategic PlanningDocumento3 pagineNew CSG Strategic PlanningErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

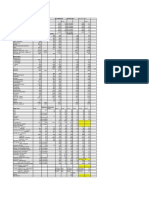

- SY 2007-2008 SY 2008-2009 SY 2009-2010 SY2010-2011 DownpaymentDocumento6 pagineSY 2007-2008 SY 2008-2009 SY 2009-2010 SY2010-2011 DownpaymentErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Nov-Dec President's Report TableDocumento5 pagineNov-Dec President's Report TableErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Proposed 2011 Xu Magna Carta of Students' Rights and Responsibilities For Undergraduate Students of Xavier University Ateneo de CagaynDocumento18 pagineProposed 2011 Xu Magna Carta of Students' Rights and Responsibilities For Undergraduate Students of Xavier University Ateneo de CagaynErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Water FountainsDocumento4 pagineWater FountainsErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Nomination For Students' ChoiceDocumento2 pagineNomination For Students' ChoiceErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Draft Magna Carta of StudentsDocumento18 pagineDraft Magna Carta of StudentsErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Application FormDocumento1 paginaApplication FormErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Competition Mechanics FinalDocumento4 pagineCompetition Mechanics FinalErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Accident Waiver and Release of Liability FormDocumento2 pagineAccident Waiver and Release of Liability FormErnesto Baconga NeriNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Seangio Vs ReyesDocumento2 pagineSeangio Vs Reyespja_14Nessuna valutazione finora

- Finding Neverland Study GuideDocumento7 pagineFinding Neverland Study GuideDean MoranNessuna valutazione finora

- Imc Case - Group 3Documento5 pagineImc Case - Group 3Shubham Jakhmola100% (3)

- German Lesson 1Documento7 pagineGerman Lesson 1itsme_ayuuNessuna valutazione finora

- ANI Network - Quick Bill Pay PDFDocumento2 pagineANI Network - Quick Bill Pay PDFSandeep DwivediNessuna valutazione finora

- PS4 ListDocumento67 paginePS4 ListAnonymous yNw1VyHNessuna valutazione finora

- Notice: Constable (Driver) - Male in Delhi Police Examination, 2022Documento50 pagineNotice: Constable (Driver) - Male in Delhi Police Examination, 2022intzar aliNessuna valutazione finora

- Bodhisattva and Sunyata - in The Early and Developed Buddhist Traditions - Gioi HuongDocumento512 pagineBodhisattva and Sunyata - in The Early and Developed Buddhist Traditions - Gioi Huong101176100% (1)

- SHS StatProb Q4 W1-8 68pgsDocumento68 pagineSHS StatProb Q4 W1-8 68pgsKimberly LoterteNessuna valutazione finora

- Iluminadores y DipolosDocumento9 pagineIluminadores y DipolosRamonNessuna valutazione finora

- Curriculum Vitae: Personal InformationDocumento2 pagineCurriculum Vitae: Personal InformationtyasNessuna valutazione finora

- Dye-Sensitized Solar CellDocumento7 pagineDye-Sensitized Solar CellFaez Ahammad MazumderNessuna valutazione finora

- 4as Lesson PlanDocumento10 pagine4as Lesson PlanMannuelle Gacud100% (2)

- Jurnal Perdata K 1Documento3 pagineJurnal Perdata K 1Edi nur HandokoNessuna valutazione finora

- ANSI-ISA-S5.4-1991 - Instrument Loop DiagramsDocumento22 pagineANSI-ISA-S5.4-1991 - Instrument Loop DiagramsCarlos Poveda100% (2)

- Hanumaan Bajrang Baan by JDocumento104 pagineHanumaan Bajrang Baan by JAnonymous R8qkzgNessuna valutazione finora

- Grope Assignment 1Documento5 pagineGrope Assignment 1SELAM ANessuna valutazione finora

- Annual Report Aneka Tambang Antam 2015Documento670 pagineAnnual Report Aneka Tambang Antam 2015Yustiar GunawanNessuna valutazione finora

- PSIG EscalatorDocumento31 paginePSIG EscalatorNaseer KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Spice Processing UnitDocumento3 pagineSpice Processing UnitKSHETRIMAYUM MONIKA DEVINessuna valutazione finora

- The Nature of Mathematics: "Nature's Great Books Is Written in Mathematics" Galileo GalileiDocumento9 pagineThe Nature of Mathematics: "Nature's Great Books Is Written in Mathematics" Galileo GalileiLei-Angelika TungpalanNessuna valutazione finora

- A Practical Guide To Transfer Pricing Policy Design and ImplementationDocumento11 pagineA Practical Guide To Transfer Pricing Policy Design and ImplementationQiujun LiNessuna valutazione finora

- Https Emedicine - Medscape.com Article 1831191-PrintDocumento59 pagineHttps Emedicine - Medscape.com Article 1831191-PrintNoviatiPrayangsariNessuna valutazione finora

- Cct4-1causal Learning PDFDocumento48 pagineCct4-1causal Learning PDFsgonzalez_638672wNessuna valutazione finora

- Ahts Ulysse-Dp2Documento2 pagineAhts Ulysse-Dp2IgorNessuna valutazione finora

- 1-Gaikindo Category Data Jandec2020Documento2 pagine1-Gaikindo Category Data Jandec2020Tanjung YanugrohoNessuna valutazione finora

- UXBenchmarking 101Documento42 pagineUXBenchmarking 101Rodrigo BucketbranchNessuna valutazione finora

- NI 43-101 Technical Report - Lithium Mineral Resource Estimate Zeus Project, Clayton Valley, USADocumento71 pagineNI 43-101 Technical Report - Lithium Mineral Resource Estimate Zeus Project, Clayton Valley, USAGuillaume De SouzaNessuna valutazione finora

- ch-1 NewDocumento11 paginech-1 NewSAKIB MD SHAFIUDDINNessuna valutazione finora

- Stress Corrosion Cracking Behavior of X80 PipelineDocumento13 pagineStress Corrosion Cracking Behavior of X80 Pipelineaashima sharmaNessuna valutazione finora