Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Consti Finals Reviewer Part 2

Caricato da

Noel Christian LucianoDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Consti Finals Reviewer Part 2

Caricato da

Noel Christian LucianoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

CASE NAME In Re Valenzuela November 9, 1998

De Castro v. JBC March 17, 2010

De Rama v. CA February 28, 2001

HELD d. Power of Appointment Issue in the interpretation of the JBC and the - Sec. 4(1) and 9 of Article 8 is the specific rule while Sec. 15, Executive Department regarding the ban on Art. 7 is the general rule appointments in the Judiciary - Sec. 15, Art. 7 is directed against two types of appointments: a) vote-buying and b) partisan consideration ISSUE: WON APPOINTMENTS TO THE - Exception to Sec. 15, Art. 7: temporary appointments to JUDICIARY ARE ALLOWED DURING THE executive position when continued vacancies will prejudice ELECTION BAN public service or endanger public safety - The prevention of vote-buying and similar evils outweighs the need for avoiding delays in filling up court vacations or the disposition of some cases - Letter of appointments must be transmitted from the office of the Chief Justice, not Malacaang APPOINTMENTS TO THE JUDICIARY ARE NOT ALLOWED DURING ELECTION BAN Resignation of CJ Puno, there is a move to fill up the - Held: No. vacancy immediately - Sec. 15, Art. 7 applies ONLY to the executive department since the prohibition is found under the section intended for the ISSUE: WON SEC. 15, ART. 7 APPLIES TO executive department APPOINTMENTS IN THE JUDICIARY - The presence of the JBC is an assurance that appointments made in the Judiciary have undergone the screening of the council before it is given to the President - Other important notes: o The appointments to the position of CJ is permanent, not one to be occupied in an acting or temporary capacity (Sec. 4(1) and 9, Art. 8). o Only the President can appoint the Chief Justice - Dissenting: o The express mention of the executive to the exceptions means that the other departments are not included in such exceptions and are covered by the ban on midnight appointments o The SC can function effectively during the midnight appointments ban without an appointed CJ because judicial power is vested in 1 SC and not to its individual members - Notes from Sir: o Judiciary is covered by the ban on midnight appointments The fact that the ban is placed under the executive department is immaterial compared to the evil sought to be avoided by the ban. Petitioner Conrado de Rama won and took the seat The CA and the CSCs decisions were correct. There was no abuse of Mayor of Pagbilao, Quezon. In 13 July 1995, he of power or violation of laws with the concerned appointments. The petitioned the Civil Service Commission (CSC) to CSC was correct in ruling that the constitutional provision being recall 14 appointments made by the previous mayor used by the petitioner did not apply in this case. The constitutional of the town. Petitioner asserts that the employees prohibition with midnight appointments only apply to presidential were midnight appointments, in violation of Sec. appointments. In fact, no law prohibits local elective officials from 15, Art. VII of the 1987 Constitution. making appointments during his or her last days of tenure. Also, the Court ruled that there was no abuse of discretion or any form of CSC ruled in favor of the respondents and denied fraud in the appointments. Respondent employees were duly petitioners request to recall the appointments. appointed after meetings of the Personnel Selection Board. They Petitioner then went to the Court of Appeals (CA) were all qualified and their appointments were duly attested by the claiming that the CSC was incorrect, and that the Head of the CSC field office at Lucena City. They already assumed previous mayor abused her power. CA ruled against their appointive positions even before the petitioner himself petitioner. assumed his elected position. COMELEC en banc appointed petitioner as Acting Director IV of the EID. Such appointment was renewed in temporary capacity twice, first by Chairperson Demetrio and then by Commissioner Javier. Later, PGMA appointed, ad interim, Benipayo Issue 1: WON the ad interim appointment of Beinpayo, Borra, and Tuason amounts to a temporary appointment prohibited by Section 1 (2) art. IX-C of the Constitution? NO. The court held that an ad interim appointment is permanent because it takes effect immediately and can no longer be withdrawn

FACTS/ISSUE

Matibag v. Benipayo April 2, 2002

as COMELEC Chairman, and Borra and Tuason as COMELEC Commissioners, each for a term of 7 yrs. The three took their oaths of office and assumed their positions. However, since the Commission on Appointments did not act on said appointments, PGMA renewed the ad interim appointments.

by the President once the appointee has qualified into office. The fact that it is subject to the confirmation of the CA does not alter its permanent character. The Constitution itself makes it permanent by making it effective until disapproved by the CA or until the next adjournment of Congress. Issue 2: WON the reappointments made by the President on the said appointments violated Sec. 1(2) art. IX-C of the Constitution? NO An ad interim appointment that is by-passed because of lack of time or failure of the CA to organize is another matter. In such case, there is no final decision by the CA. Absent such decision, the President is free to renew the ad interim appointment of a bypassed appointee. This is recognized in Sec. 17 of the Rules of the Commission on Appoinments. Hence, a by-passed appointment can be considered again if the president renews the appointment An ad interim appointment that has lapsed by inaction of the CA does not constitute a term of office. The period from the time the ad interim appointment is made to the time it lapse is neither a fixed nor an unexpired term. The ad interim appointments and subsequent renewals of the appointment s of Benipayo, Borra, and Tuason do not violate the prohibition on reappointments because there were no previous appointments that were confirmed by the CA. The same ad interim appointments and renewals of appointments will also not breach the seven-year term limit because the appointments are for a fixed term expiring on Feb 2, 2008.

Larin v. Executive Secretary October 16, 1997

Barrioquinto v. Fernandez January 21, 1949

Larin, Assistant Commissioner of the Excise Tax Issue relevant to the topic in the outline: WON the president has Service of BIR, Presidential appointee, classified as the power to discipline the petitioner. YES. Career Executive Service Officer. Convicted by Sanduganbayan for violation of the Petitioner is a presidential appointee who belongs to career service National Internal Revenue Code. The conviction was of the Civil Service. Thus, he comes under the direct disciplining reported to the President. Executive Secretary authority of the President. That the power to remove is inherent in Quisumbing then issued MO 164, based on this the power to appoint conferred to the President by the Constitution conviction creating a committee to investigate the (Section 16, Article VII) is well-settled. MO 164 was then validly administrative complaint against him. During the issued pursuant to such power of removal. pendency of the investigation, the President Notwithstanding, the power of removal is not absolute. Under the reorganized the bureau which abolished the office Administrative Code of 1987 and even the Constitution itself, the formerly occupied by Larin. Then the investigative petitioner enjoys the right of security of tenure. The Civil Service committee found him guilty of misconduct punishing Decree provides that a career service officer enjoying security of him with forfeiture of his leave credits and retirement tenure may be removed only for causes enumerated in said law. benefits, including disqualification from Hence, the petitioner is a recipient of tenurial protection and his reappointment. The instant petition was then filed. removal must be in accordance to procedural due process. During its pendency, SC set aside the conviction of the petitioner in the criminal cases which found him guilty of grave misconduct. e. Executive Clemency Petitioners Norberto Jimenez and Loreto YES. Barrioquinto charged with the crime of murder . Pardon: Before expiration of the period for perfecting an - granted by the Chief Executive appeal, Jimenez became aware of the - a private act which must be pleaded and proved by the person Proclamation No. 8, dated September 7, 1946, pardoned, because the courts take no notice thereof which grants amnesty in favor of all persons who - looks forward and relieves the offender from the consequences may be charged with an act penalized under the of an offense of which he has been convicted RPC in furtherance of the resistance to the enemy Amnesty: or against persons aiding in the war efforts of the - by Proclamation of the Chief Executive with the concurrence of enemy. Issued by Pres. Manuel Roxas based on Congress Art. VII, Sec. 10, par. 6 of Consti. Jimenez and - a public act of which the courts should take judicial notice

Barrioquinto submitted ther cases to the GAC. GAC returned the cases of the petitioners to CFI Zamboanga without deciding WON they are entitled to the benefits of the said Amnesty Proclamation, because Barrioquinto and Jimenez did notadmit committing the offense.

Vera v. People 1963

Petitioners Vera, Figueras, Ambas, Flordio, Bayran, and 92 others were charged with the complex crime of kidnapping with murder of Lozaes. They invoked the benefits of the Amnesty Proclamation of the President so the case was referred to the Eight Guerilla Amnesty Commission, which tried it. During the hearing, none of the accused admitted to the crime charged. In view of this, the Amnesty Commission rendered a decision stating it could not take cognizance of the case on the ground that the benefits of the Amnesty Proclamation could only be invoked by defendants by admitting to the commission of the crime and plead that said commission was in pursuance of the resistance movement and perpetrated against persons who aided the enemy during Japanese occupation. The Amnesty Commission remanded the case to the court of origin for trial. Teofilo Santos was charged and convicted with crime of estafa. Despite his conviction, Santos continued to be a registered elector in the municipality of Malabon, Rizal, and was, for a time, seated as the municipal president of that municipality. Subsequently, the Election Code was approved which included section 94, paragraph (b) of which disqualifies the respondent from voting for having been "declared by final judgment guilty of any crime against the property." In view of this provision, Santos applied for an absolute pardon. His request was granted, restoring him to his "full civil and political rights, except that with respect to the right to hold public office or employment, he will be eligible for appointment only to positions which are clerical or manual in nature and involving no money or property responsibility." Now, Miguel Cristobal, filed a petition for the exclusion of the name of Teofilo Santos from the list of voters on the ground that the latter is disqualified under paragraph (b) of section 94 of the Election Code.

- granted to classes of persons or communities who may be guilty of political offenses - looks backward and abolishes and puts into oblivion the offense itself - In order to entitle a person to the benefits of the Amnesty Proclamation of September 7, 1946, it is NOT necessary that he should admit having committed the criminal act or offense with which he is charged, and allege the amnesty as a defense,it is sufficient that the evidence shows that the offense committed comes within the terms of said Amnesty Proclamation. WON persons invoking the benefit of the amnesty should first admit to having committed the crime of which they were accused.-YES COURT: Amnesty presupposes the commission of a crime, and when the accused maintains that he has not committed a crime, he cannot have any use for amnesty. The invocation of an amnesty is in the nature of a plea and avoidance, which means the accused admits the allegations against him but disclaims liability therefor on account of intervening facts within the scope of the amnesty proclamation. Amnesty cannot be invoked where the accused denies the commission of the offense charged. WON the present case was within the terms of the Amnesty Proclamation COURT: The facts established before the Amnesty Commission did not bring the present case within the terms of the Amnesty Proclamation. In the case at bar, the killing of the victim was not in furtherance of the resistance movement, but was due to the rivalry between the Hunters guerilla, to which the victim belonged, and Veras Guerilla to which the accused belonged. WON Santos hould be excluded from the list of registered voters. There are 2 limitations on the exercise of this constitutional prerogative by the Chief Executive: (1) that the power be exercised after convictions; and (2) that such power does not extend to cases of impeachment. An absolute pardon not only blots out the crime committed, but removes all disabilities resulting from the convictions. When granted after the term of imprisonment has expired, absolute pardon removes all that is left of the consequences of conviction. In the present case, while the pardon extended to respondent Santos is conditional in the sense that "he will be eligible for appointment only to positions which are clerical or manual in nature involving no money or property responsibility," it is absolute insofar as it "restores the respondent to full civil and political rights Petition of Cristobal denied.

Cristobal v. Labrador 1941

Monsanto v. Factoran February 9, 1989

In 1983, Salvacion Monsanto, the petitioner, who was assistant treasurer of Calbayog City was convicted by the Sandiganbayan for the complex crime of estafa and was sentenced for imprisonment. Monsanto appealed her conviction to the Supreme Court which affirmed the same. She then filed a motion for reconsideration which

The Ministry of Finance referred the request of Monsanto to the Office of the President which gave a statement through its Deputy Executive Secretary that it is only during an acquittal, not absolute pardon, as the only ground for reinstatement of previous position and entitlement of salary payment of a public officer. The petitioner, being convicted for the crime of estafa with a penalty of prision correccional carries with it the accessory penalty of suspension from public office.

during the pendency of that motion, she was extended pardon by then President Marcos absolute pardon which she accepted on December 21, 1984. By reason of the said pardon, Monsanto requested the Ministry of Finance that she be restored to her former post, being vacant and stressing that the absolute pardon has wiped out the crime implying that her service to the government has never been interrupted thus entitling her to reinstatement from the date of her preventive suspension and a back pay. The basic theory of the petitioner is that having her case pending final judgment during the extension of executive clemency, her employment was therefore not terminated or forfeited. Marcelino Lontok was convicted by CFI-Zambales of the crime of bigamy which was affirmed by the Supreme Court on appeal. After this conviction, a pardon was issued by Gov. Gen. Harrison remitting the sentence of Lontok on condition that he shall not again be guilty of any misconduct. However, the Atty. Gen. asks the Court that an order be issued for the disbarment of Lontok by reason of this conviction of a crime involving moral turpitude. Issue: WON the effect of the pardon granted to Lontok bars subsequent actions soliciting his disbarment.

The Supreme Court affirmed the resolution of Deputy Executive Secretary stating that the pardon granted to the petitioner has resulted in removing her disqualification from holding public employment but that cannot go beyond it. That to regain her former post, she must reapply and undergo the usual procedure required for a new appointment. That in considering her qualifications and suitability for the public post, the facts constituting her offense must be and should be evaluated and taken into account to determine ultimately whether she can once again be entrusted with public funds.

In Re Lontok 1923

It has been held that a pardon operates to wipe out the conviction and is a bar to any proceeding for the disbarment of the attorney after the pardon has been granted. However, where the proceedings to disbar are founded on the PROFESSIONAL MISCONDUCT involved in a transaction culminating in the conviction of a felony, the pardon still has the effect of relieving him of penal consequences, but IT DOES NOT operate as a bar to the disbarment proceeding. In Ex Parte Garland, the court through Justice Field lays the effect of the granting of pardon a. Pardon reaches both punishment and the guilt b. When pardon is full, it releases the punishment and blots out the guilt c. If granted BEFORE conviction, it prevents any penalties and disabilities, consequent upon conviction d. If granted AFTER conviction, it removes any penalties and disabilities, restores all civil rights e. Only LIMITATION: does not restore offices forfeited, property or interests vested in others in consequence of the conviction . Here, the motion for disbarment is based solely on the judgment of conviction of a crime to which Lontok is pardoned. The language of the pardon does not amount to a conditional pardon. However, if Lontok should be again convicted, the pardon condition violated, he would then be subject to disbarment. Court said that the since the pardon was extended by the Executive, the determination of whether or not it has been breached is up to the Executive, not to the Courts. This Court in effect held that since the petitioner was a convict who had already been seized in a constitutional way, been confronted by his accusers and the witnesses against him -, been convicted of crime and been sentenced to punishment therefor, he was not constitutionally entitled to another judicial determination of whether he had breached the condition of his parole by committing a subsequent offense. The executive clemency under it is extended upon the conditions named in it, and he accepts it upon those conditions. The status of our case law on the matter under consideration may be summed up in the following propositions: 1. The grant of pardon and the determination of the terms and conditions of a conditional pardon are purely executive acts which are not subject to judicial scrutiny. 2. The determination of the occurrence of a breach of a condition of a pardon, and the proper consequences of such breach, may be either a purely executive act, not subject to judicial scrutiny under

Torres v. Gonzales 1987

Wilfredo Torres was convicted of a crime in 1979 and sentenced to serve a prison term of 11 years, 10 mos and 22 days to 38 years, 9 mos and 1 day. He was given a conditional pardon on April 18 1979 on the condition that he would not again violate any of the penal laws of the Philippines. On May 21 1986, the Board of Pardons and parole resolve the recommend the cancellation of the pardon, having found out that Torres has been charged with 20 counts of estafa at the Quezon City Trial Court, convicted of sedition by the QC Trial Court on June 26 1985 and had been accused of other crimes such as swindling, grave threats, grave coercion, illegal possession of firearms, etc. He was arrested and recommitted on October 10 1986, and confined in Muntinlupa to serve the unexpired portion of his sentence.

IBP v. Zamora August 15, 2000

Section 64 (i) of the Revised Administrative Code; or it may be a judicial act consisting of trial for and conviction of violation of a conditional pardon under Article 159 of the Revised Penal Code. Where the President opts to proceed under Section 64 (i) of the Revised Administrative Code, no judicial pronouncement of guilt of a subsequent crime is necessary, much less conviction therefor by final judgment of a court, in order that a convict may be recommended for the violation of his conditional pardon. Because due process is not semper et ubique judicial process, and because the conditionally pardoned convict had already been accorded judicial due process in his trial and conviction for the offense for which he was conditionally pardoned, Section 64 (i) of the Revised Administrative Code is not afflicted with a constitutional vice. The Court however noted that Torres must still be convicted by final judgment of the crimes with which he was charged before the criminal penalty can be imposed upon him. The decision to take back the pardon is valid. f. Commander-in-Chief Invoking his powers as Commander-in-Chief When the President calls the armed forces to prevent or suppress under Sec. 18, Art. VII of the Constitution, the lawless violence, invasion or rebellion, he necessarilyexercises a President directed the AFP Chief of Staff and discretionary power solely vested in his wisdom. Under Sec. 18, Art. VII PNP Chief to coordinate with each other for the of the Constitution, Congress may revoke such proclamation of martial proper deployment and utilization of the law or suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus and the Marines to assist the PNP in preventing or Court may review the sufficiency of the factual basis thereof. However, suppressing criminal or lawless violence. The there is no such equivalent provision dealing with the revocation or President declared that the services of the review of the Presidents action to call out the armed forces. The Marines in the anti-crime campaign are merely distinction places the calling out power in a different category from the temporary in nature and for a reasonable period power to declare martial law and power to suspend the privilege of the only, until such time when the situation shall writ of habeas corpus, otherwise, the framers of the Constitution would have improved. The IBP filed a petition seeking have simply lumped together the 3 powers and provided for their to declare the deployment of the Philippine revocation and review without any qualification. Marines null and void and unconstitutional. The reason for the difference in the treatment of the said powers Issues: highlights the intent to grant the President the widest leeway and (1) Whether or not the Presidents factual broadest discretion in using the power to call out because it is determination of the necessity of calling the considered as the lesser and more benign power compared to the power armed forces is subject to judicial review to suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus and the power to (2) Whether or not the calling of the armed impose martial law, both of which involve the curtailment and forces to assist the PNP in joint visibility patrols suppression of certain basic civil rights and individual freedoms, and violates the constitutional provisions on civilian thus necessitating safeguards by Congress and review by the Court. supremacy over the military and the civilian character of the PNP In view of the constitutional intent to give the President full discretionary power to determine the necessity of calling out the armed forces, it is incumbent upon the petitioner to show that the Presidents decision is totally bereft of factual basis. The present petition fails to discharge such heavy burden, as there is no evidence to support the assertion that there exists no justification for calling out the armed forces. 1. Petitioners assail PP 1946 and AO 273 issued by the President Arroyo, pacing Maguindanao, Sultan Kudarat and Cotabato City under state of emergency, directing the AFP and the PNP to prevent and suppress lawless violence, and delegated supervision of the ARMM to DILG. They argue that the issuances encroached upon ARMMs autonomy since DILG could suspend ARMM officials. Petitioners claimed that the declaration of state of emergency has no factual basis, especially in Sultan Kudarat and 1. The court stated that the claim of the petitioners is anchored on the allegation that the DILG Secretary was authorized to take over the operations of the ARMM and assume direct governmental powers over the region. a. However, the DILG Secretary did not take over control of the powers of the ARMM. b. After the ARMM Governor was taken into custody for alleged complicity in the Maguindanao massacre, the Vice-Governor assumed the post and subsequently assigned a person to serve as Acting Vice-Governor. The court also said that deployment of AFP and PNP is not by itself an exercise of emergency powers as understood under Section 23(2), Article VI of the Constitution.

Ampatuan v. Puno June 7, 2011

2.

2.

3.

Cotabato City, where no critical violent incidents occurred. Respondents on the other hand deny the alleged deprivation of regional autonomy and argued that the President merely exercise the calling out power. Also, it was contended that the determination of the need for its exercise rests solely on the wisdom of the President.

a.

3.

The President did not proclaim a national emergency, only a state of emergency. b. She did not act pursuant to any congressional enactment authorizing her to exercise extraordinary powers. c. The calling out of the armed forces is a power directly vested in the President and does not need congressional authority to be exercised. It was then pointed out that while the court may inquire into the factual bases for the President's exercise of the calling out power, it would generally defer to her judgment on the matter. a. Unless it is shown that such determination was attended by grave abuse of discretion, the Court will accord respect to the President's judgment. b. Here, petitioners failed to show that the declaration of a state of emergency, as well as the President's exercise of the calling out power had no factual basis. c. They simply alleged that, since not all areas under the ARMM were placed under a state of emergency, it follows that the take over of the entire ARMM by the DILG Secretary had no basis too. d. Apart from the fact that there was no such take over, the OSG also clearly explained the factual bases for the President's decision to call out the armed forces, namely, the imminence of violence and anarchy and the possibility of further bloodshed and hostilities in the places mentioned.

Sanlakas v. Executive Secretary February 3, 2004 -

Three hundred junior officers and enlisted men from the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) staged a mutiny by storming the Oakwood Premiere apartments in Makati City on July 27, 2003 The mutineers cried of corruption in the Armed Forces of the Philippines; demanded for the resignation of the President, the Secretary of Defense, and the Chief of the Philippine National Police (PNP) In lieu of the said mutiny, the President issued Proclamation No. 427 and General Order No. 4, both declaring a state of rebellion and called on the AFP to suppress the rebellion The mutiny ended on the evening of July 27, 2003 After negotiations with the soldiers to return to their barracks, the President lifted the state of rebellion five days later on August 1, 2003, through Proclamation No. 435 Petitioners Sanlakas, PartidoManggagawa (PM), and Social Justice Society (SJS), in relation to Section 18, Art. VII of the Constitution, contend that: o The declaration of a state of rebellion is not required to call out the armed forces o Due to the cessation of the rebellion, there exists no factual basis for the imposition of a

Petitions are moot and academic, although the Supreme Court recognizes jurisdiction over cases that are capable of repetition yet evading review - The petitions are deemed moot and academic, because the state of rebellion has been lifted already on August 1, 2003 - The Lacson vs. Perez precedent proved that this case is capable of repetition; in the said case, an angry mob that stormed Malacanang on May 1, 2001 has compelled the President to call upon the AFP and PNP to suppress the rebellion through Proclamation No. 38 and General Order No. 1 - In this case, the Supreme Court went on to assess the validity of the Presidents declaration Petitioners Sanlakas, PM, and SJS, haveno legal standing to sue; Petitioners Suplico et al. and Pimentel (Members of Congress)have standing to sue - Whereas petitioners Sanlakas et al. are considered peoples organizations that represents the interest of the people, the Supreme Court is still observant of the rule that only real parties in interest or those who would suffer a direct injury from the controversy, are the ones who may invoke the judicial power - Petitioners Members of Congress have made clear the validity of their legal standing, since their contention involving the alleged usurpation of the President of their constitutional power speaks of their incurrence of direct damage For purposes of exercising the calling out power, the President is not required to declare a state of rebellion - Section 18, Art. VII of the Constitution: whenever it becomes necessary, he may call out such armed forces to prevent or suppress lawless violence, invasion or rebellion. - Section 18, Art. VII of the Constitution grants the President, in her capacity as Commander-in-Chief, the following powers: o Calling out power

state of rebellion in an indefinite period (the mutiny ended on the evening of July 27, 2003; the state of rebellion ensued for five days until August 1, 2003) The report circumvents the report requirement, which requires the President to make a report 48 hours after the proclamation of martial law Petitioner Suplico, et al., contends that the declaration of a state of rebellion by the President is an indirect exercise of emergency powers o Said petitioner contends that under Section 23 (2), Art. VII of the Constitution, such exerciseof emergency powers is exclusive to Congress, and that the declaration made by the President thus results to the latters usurpation of their said exclusive power Petitioner Senator Pimentel contends that the presidential issuances constitute an unwarranted exercise of martial law power, which is baseless under the Constitution o Said petitioner fears that the said declaration of the President may pave way for the unconstitutional imposition of warrantless arrests o

o Power to suspend the writ of habeas corpus o Power to declare martial law In order for the President to exercise the latter two powers, these two conditions must exist: o Actual invasion or rebellion o Exercise of said power required for ensuring public safety The aforementioned conditions are not required in the exercise of the calling out power The Constitution of the United States of America (USA) serves as the foundation of the overall concept of the Presidents power as Chief Executive and Commander-In-Chief Residual executive powers of the President, as suggested by Justice Cortes, rests upon the President o Such is due to the highly unitary and centralized nature of the Philippines government o Exemplified in Marcos vs. Manglapus, wherein residual executive power is practiced by the President by barring the return of former President Marcos due to perceived threats of destabilization against the government and other forms of sociopolitical disturbances

There is factual basis for the implementation of a state of rebellion - Section 18 (3), Art. VII of the Constitution: The Supreme Court may review, in an appropriate proceeding filed by any citizen, the sufficiency of the factual basis for the proclamation of martial law or the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus or the extension thereof, ad must promulgate its decision thereon within three days from its filing. - No proof was shown by the petitioners that the President has acted without factual basis Power exercised by the President in declaring a state of rebellion and in calling out the armed forces is in consonance with her powers as Chief Executive and Commander-in-Chief - There was no instance wherein the President has acted beyond her powers as both Chief Executive and Commander-in-Chief No. Said declarations are not tantamount to the declaration of martial law - No indication that military tribunals have taken over jurisdiction over civil courts - No indication of curtailment of civil and political rights - No indication of Presidents encroachment of other branches of government - No indication of attempt, at all, that President attempted to exercise martial law

1. David v. Arroyo May 3, 2006

Petitioners assail the constitutionality of PP 1017 and GO 5 issued by President Arroyo on February 24, 2006 (celebration of the 20th Anniversary of the EDSA People Power I), declaring a state of national emergency and commanding the AFP to maintain law and order throughout the Philippines, prevent or suppress all forms of lawless violence as well as any act of insurrection or rebellion and to enforce obedience to all the laws and to all

1.

Petitioners assail PP 1017 as without factual basis. The court responded thus: a. The nature of the Presidents calling out power as a discretionary power does not prevent an examination of whether such power was exercised within permissible constitutional limits. b. Such examination, however, is limited to the determination of arbitrariness, not correctness. This means that, as in IBP v. Zamora, the petitioners must show that PP 1017 is totally bereft of factual basis.

decrees, orders and regulations promulgated by me personally or upon my direction. GO 5 also included the phrase acts of terrorism.

c. d.

2.

3.

4.

5. 6.

The petitioners failed to do this. On the other hand, the respondents were able to show detailed narration of events leading to the issuance of PP 1017, including intelligence reports regarding escape of the Magdalo Group, defections in the military, and the growing alliance between them and the NPA. Petitioners contend that PP 1017 is void on its face for being overbroad since its enforcement encroaches on both unprotected and protected rights. The court responded thus: a. The overbreadth doctrine is for free speech cases. b. PP 1017 is not primarily directed at to speech or speechrelated conduct. Instead, it pertains to a spectrum of conduct manifestly subject to state regulation. c. Also, facial challenge is generally disfavored since petitioners may be allowed to raise speculative rights of third parties, contrary to usual rules. d. The petitioners themselves were not able to mount it successfully for failure to show that the law is invalid in every instance. e. As for the vague for vagueness claim, they failed to establish that men of common intelligence cannot understand the meaning and application of PP 1017. PP 1017 may be divided into three provisions: calling out power, take care power, and take over power. a. PP 1017 invoked the calling out power of the President, which is part of a sequence of graduated powers granted by the Constitution (calling-out power, power to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, and power to declare martial law). b. Related to the take care power, PP 1017 is unconstitutional insofar as it grants the President the authority to promulgate decrees, way beyond the grant of ordinance power. c. The take over power is an exercise of an emergency power, not like the power to declare a state of emergency. The former needs a delegation of power from the Congress as the repository of emergency powers. Without such delegation, the President may not exercise said powers. While there are evidence of abuse committed by those who implemented PP 1017, this court cannot declare it unconstitutional on such ground. GO 5 was issued in accordance with the power of the President to direct subordinates to implement PP 1017. The words acts of terrorism however should be considered deleted since there is no law defining such and no limitations imposed upon the AFP in carrying out said portion of GO 5. 1. YES. Five justices held that the question is political and should not be determined by court. (Makasiar, Antonio, Esguerra, Fernandez and Aquino) Fernandez adds that as a member of the 1973 Convention he believes that the as a member of the Convention, they have put an imprimatur on the proposition of the validity of a martial law proclamation Barredo believes that political question are not per se beyond the courts jurisdiction, judicial power vested in it by the Constitution being all-embracing and plenary but as a matter of policy should abstain from interfering with the Executives Proclamation. Esguerra finds that the declaration of martial law is final and conclusive upon the courts. Antonio finds that there is no dispute as to the existence of a state of rebellion and on that

Aquino v. Enrile 1974

This is a consolidated petition for writs of habeas corpus for the release of petitioners and/or removal of the prohibition for them to travel outside the Greater Manila Area, claiming that Proclamation No. 1081, which declared Martial Law in the Philippines, unconstitutional and therefore void. The petitioners were detained under Order No. 2, for being participants or for having given aid and comfort in the conspiracy to seize political and state power in the country and to take over the Government by force. The ponencia was supposed to written by Justice Barredo, but the

majority of the Court is of the opinion that since the decision herein would be recorded in history for posterity, every Justice should be given the chance to explain his/her views, hence the nine separate opinions on the matter. Hence, individualization rather than consensus became the order of the day, even though the decision for dismissing all the petitions was unanimous. The petitions can be grouped into three: a. Aquinos petition for writ of habeas corpus, for release from detention under General Order No. 2, for being a participant in a conspiracy to wrest political and state power from the government b. Rodrigo et als petition for writ of habeas corpus, praying for permission to go beyond the GMA boundaries, having been released from detention subject to certain conditions c. Dioknos petition for writ of habeas corpus, having been detained for more than a year already Of the three groups, only Aquinos petition is justiciable because Rodrigo et als prayers were already considered moot and academic, having been released from their detention already and the confinement of their movement to GMA with factual basis. Diokno, for his part, has withdrawn his petition, believing that justice will not be served him, and also a few days before the promulgation of the SC decision he was released from military custody, making his case moot and academic as well. In Aquinos case, formal charges for subversion, murder and illegal possession of firearms were already filed against him, hence the prayer for habeas corpus would not prosper because there is already reason enough for his detention under the military commission. - Civilian petitioners were arrested and charged with subversion. - Military Commission No. 34 was created to try the criminal cases against them. - They were found guilty and sentenced to death. - Petitioners were praying that they be granted petitions for habeas corpus, certiorari, prohibition, and mandamus. - Martial law was eventually lifted, revoking G.O. No. 8 (creating military tribunals), and petitioners were eventually released. Issue: WON military commissions or tribunals have the jurisdiction to try civilians for offences committed during martial law (when civil courts were still opening and functioning). - Members of the military were charged in court in relation to the Oakwood mutiny. Some of their cases were dismissed, with

premise emphasizes the factor of necessity for the exercise of the president under the 1935 Constitution to declare martial law. Four on the side of justiciability: Castro, Fernando, Teehanke and Munoz Palma. The constitutional sufficiency may be inquired into by court and would thus apply the principle laid down by Lansang although the case refers to the power of President to suspend habeas corpus. The recognition of justiciability in Lansang is there distinguished from the power of judicial review and is limited to ascertaining whether the President has gone beyond the constitutional limits of his jurisdiction, not to exercise the power vested in him or to determine the wisdom of the act. The Test is whether in suspending the writ of habeas corpus, the president he did or did not acted arbitrarily (bias, capricious). Applying the test, the Justices find no arbitrariness in the Presidents proclamation of martial law pursuant to the 1935 Constitution. The bases for the suspension of the privilege of writ of habeas corpus, with regards to the existence of a state rebellion in the country, had not disappeared but had even worsened. The question of the validity of the Proclamation no 1081 has been foreclosed by the transitory provision of the 1973 Constitution (Art XVII. Sec 3 (2)) that all proclamations, orders, decrees, instructions, and acts promulgated, issued or done by the incumbent President shall be part of the law of the land and shall remain valid, legal, binding and effective even after the ratification of this Constitution. The political or justiciable question controversy has become moot and purposeless as a consequence of the referendum of July 27-28, 1973. The question which was overwhelmingly voted upon by a majority of voters, even between 15 and 18 years of age in affirmative: Under the 1973 Constitution, the President, if he so desires, can continue in office beyond 1973 and finish the reforms he initiated under martial law? YES. The petitions should be dismissed with respect to petitioners who have been released from detention but have not withdrawn their petitions because they are still subject to certain restrictions. Implicit in the state of martial law is the suspension of the privilege of writ of habeas corpus with respect to persons arrested or detained for acts related to the basic objective of the proclamation: to suppress invasion, insurrection, rebellion or to safeguard public safety against imminent danger thereof. Military commissions/tribunals have no jurisdiction on such cases. The Court reviewed and reversed itself on Aquino, Jr. v. Military Commission No. 2, which allowed military tribunals to have jurisdiction during martial law. - Animas v. The Minister of National Defense ordered the transfer of proceedings to civil courts after the lifting of ML. - Due process law demands that the trial entitled to the accused is a trial by judicial process, not by military tribunals (dissent in Aquino, Jr.) - Trying cases is not the function of the Executive Department through the military authorities. If the civilian courts are open and functioning, they have the jurisdiction. Due process rights would be violated if the military had jurisdiction. Habeas corpus dismissed for being moot and academic (they were released already). Certiorari and prohibition granted. Petitioners were not entitled to the writs prayed for. RTCs declaration was declared null and void. The declaration was in violation of Section 1 of RA 7055 -

Olaguer v. Military Commission Gancayco, J 1987

Navales v. Abaya Callejo, Sr, J

October 25, 2004

the RTC declaring that the charges before the Court-Martial were not serviceconnected, but were in furtherance of coup detat. - Petitioners were charged before the General Court-Martial anyway. They now assail the charges against them, claiming that they cannot be charged because of the RTCs declaration. Issue: WON petitioners were entitled to the writs of prohibition and habeas corpus. De villa was convicted of raping his niece (niece got pregnant and gave birth). Three years after he discovered DNA evidence that he was not the father of the child. Petitioner contends that the decision on 2001 must be overturned in light of the new evidence presented.

In Re De Villa November 17, 2004

(jurisdiction of trial courts). The RTC acted without or in excess of jurisdiction. - RA 7055 did not divest the military courts of its jurisdiction to try cases involving the Articles of War. In fact, the AW considers their offenses as service-connected. - Habeas corpus cannot be granted where the person alleged to be restrained is in the custody of an officer under a process issued by the court which has jurisdiction. - It cannot also be granted when person has been charged before any court or quasi-judicial body. - Prohibition cannot be granted also when the General CourtMartial has jurisdiction, as in this case. Petitions denied. WON the issuance of writ of Habeas Corpus to release an individual already convicted and serving sentence by virtue of a final and executory judgment is appropriate WON the Court should grant a new trial 1.No. review of a judgment of conviction is allowed in a petition for issuance of the writ of habeas corpus when as a consequence of a proceeding: a. there has been a deprivation of a constitutional right resulting in the restraint of a person. b. Court had no jurisdiction to impose the sentence c. Excessive sentence has been imposed, as such sentence is void as to the excess. In this case invokes the writ to assail the final judgment without providing a legal basis. Petitioner neither alleges a b or c (above) Mere errors of fact or law, which did not have the effect of depriving the trial court of its jurisdiction over the case and the person of the defendant, are not correctible in a petition for the issuance of the writ of habeas corpus; if at all, these errors must be corrected on certiorari or on appeal, in the form and manner prescribed by law.

Constantino v. Cuisia October 13, 2005

e. Emergency Powers h. Contracting and Guaranteeing Foreign Laws Petitioners are assailing the contracts entered into Held: pursuant to the Philippine Comprehensive Financing 1. No, it allows the President to contract and guarantee foreign Program. loans. It makes no prohibition on the issuance of certain kinds of loans or distinctions as to which kinds of debt instruments The purpose of the Financing Program is to manage are more onerous than others. our debts. Its a restructuring agreement with foreign government and commercial bank creditors. It The only restriction that the Constitution provides, aside from prior implemented 2 debt-relief options: (1) Cash buyback concurrence of the Monetary Board, is that the loans be subject to of portions of the Philippine foreign debt at a limitations provided by law. This law is RA 245 which allows foreign discount and (2) Allowed creditors to convert loans to be contracted in the form of bonds existing Philippine debt instruments into any of 3 kinds of bonds/securities PD 1177- the president is empowered to execute debt payments without the need for further appropriations. Issues: 1. WON the debt-relief contracts entered into pursuant to the Financing Program is beyond the powers granted to the President under Section 20, Article VII of the Constitution. WON the power to enter into such contracts resides solely on the President and cant be delegated. Section 2, RA 240-authority for buyback loans. It also allows president to pre-terminate debts without further action from Congress. President cant be empowered to borrow money only to be bereft of authority to implement the payment despite appropriations for it. The authority to contract loans includes the power to effect payments for it. 2. Doctrine of Qualified Political Agency Heads of executive department are subject to the direction of the

2.

President. Each head is the presidents alter ego. The Secretary of Finance, as the alter ego of the President, can implement the scheme of a policy the President, herself, expressed. 3 Powers the President cant be delegated: 1. Suspension of writ of habeas corpus 2. Proclamation of Martial Law 3. Pardoning power

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Purita Alipio, Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals and Romeo G. Jaring, Represented by His Attorney-In-Fact RAMON G. JARING, RespondentsDocumento6 paginePurita Alipio, Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals and Romeo G. Jaring, Represented by His Attorney-In-Fact RAMON G. JARING, RespondentsulticonNessuna valutazione finora

- RP vs. CA & LastimadoDocumento3 pagineRP vs. CA & LastimadoTrisNessuna valutazione finora

- Home Bankers Savings vs. CA, Et. Al. DigestDocumento4 pagineHome Bankers Savings vs. CA, Et. Al. DigestXyrus BucaoNessuna valutazione finora

- 001rule 131 Sec. 3 Disputable Presumptions 20 Files Merged 2 Files MergedDocumento399 pagine001rule 131 Sec. 3 Disputable Presumptions 20 Files Merged 2 Files MergedRomz NuneNessuna valutazione finora

- Commonwealth Insurance Corporation vs. Ca: Insurance Company, Inc. We Have Sustained TheDocumento6 pagineCommonwealth Insurance Corporation vs. Ca: Insurance Company, Inc. We Have Sustained TheAisha TejadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Family Code of The Philippines: The Family Home Ponente: Justice CoronaDocumento2 pagineFamily Code of The Philippines: The Family Home Ponente: Justice CoronaJanmari G. FajardoNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Tickler 2nd PFR SyllabDocumento13 pagineCase Tickler 2nd PFR SyllabAlexis Dominic San ValentinNessuna valutazione finora

- Sereno CaseDocumento17 pagineSereno CaseJanice F. Cabalag-De VillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Glossary of Terms of International LawDocumento7 pagineGlossary of Terms of International LawximeresNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Write A Case BriefDocumento1 paginaHow To Write A Case Briefstephanie_patiño_4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Personal ReviewerDocumento15 paginePersonal ReviewerMark Pelobello MalhabourNessuna valutazione finora

- 42 Navaja V People 62215 PrinciplesDocumento1 pagina42 Navaja V People 62215 PrinciplesAli NamlaNessuna valutazione finora

- 12th Final Digest ZacariasDocumento1 pagina12th Final Digest ZacariasJoshua ParilNessuna valutazione finora

- Sps. Manuel vs. OngDocumento4 pagineSps. Manuel vs. OngMaria Francheska GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Recognition and International Legal Personality of Non-State ActorsDocumento11 pagineRecognition and International Legal Personality of Non-State ActorsestiakNessuna valutazione finora

- Trademark BasicsDocumento3 pagineTrademark BasicsAnuj DubeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Labor Law 1 ReviewerDocumento156 pagineLabor Law 1 ReviewerDarwin AbesNessuna valutazione finora

- 1315-1319 - Stages and Essential Requisites of ContractsDocumento2 pagine1315-1319 - Stages and Essential Requisites of ContractsSarah Jane UsopNessuna valutazione finora

- Labor Frequently Asked QuestionsDocumento7 pagineLabor Frequently Asked QuestionsEstela BenegildoNessuna valutazione finora

- Ricardo A. Llamado V Honorable Court of Appeals and Leon Gaw G.R. No. 84850Documento1 paginaRicardo A. Llamado V Honorable Court of Appeals and Leon Gaw G.R. No. 84850cyndijocelleNessuna valutazione finora

- Llamado V CADocumento9 pagineLlamado V CAMp CasNessuna valutazione finora

- Civil Procedure 37 - de Castro v. de Castro Jr. GR No. 172198 16 Jun 2009 SC Full TextDocumento11 pagineCivil Procedure 37 - de Castro v. de Castro Jr. GR No. 172198 16 Jun 2009 SC Full TextJOHAYNIENessuna valutazione finora

- Labrel 2019Documento11 pagineLabrel 2019NajimNessuna valutazione finora

- Director of Lands v. CA and Bisnar, October 26, 1989Documento3 pagineDirector of Lands v. CA and Bisnar, October 26, 1989ZeaweaNessuna valutazione finora

- NPC V CaDocumento5 pagineNPC V Caapril75Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sheker vs. Sheker GR No. 157912 December 13, 2007 Case FlowDocumento2 pagineSheker vs. Sheker GR No. 157912 December 13, 2007 Case FlowJoshua Erik MadriaNessuna valutazione finora

- Prebar Notes On Crim Pro UpdatedDocumento184 paginePrebar Notes On Crim Pro UpdatedMyrtle VivaNessuna valutazione finora

- Persons and Family Relations SyllabusDocumento3 paginePersons and Family Relations SyllabusMikkaEllaAnclaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nepomuceno vs. NarcisoDocumento2 pagineNepomuceno vs. NarcisoDenise Jane Duenas100% (1)

- Evidence Part 1 PDFDocumento26 pagineEvidence Part 1 PDFpa3ckblancoNessuna valutazione finora

- Case No. 15: Apolonio de Los Santos Versus Benjamin V. LimbagaDocumento2 pagineCase No. 15: Apolonio de Los Santos Versus Benjamin V. LimbagaAlmiraNessuna valutazione finora

- 427 LANDERIO Solid Homes Inc., V PayawalDocumento1 pagina427 LANDERIO Solid Homes Inc., V PayawalCarissa CruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Non-State Actors' Human Rights Obligations and Responsibility Under International LawDocumento10 pagineNon-State Actors' Human Rights Obligations and Responsibility Under International LawKim DayagNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 (EDITED) Yap SR V SiaoDocumento4 pagine2 (EDITED) Yap SR V SiaoRioNessuna valutazione finora

- GOPOCO GROCERY V PACIFIC COAST BISCUITDocumento1 paginaGOPOCO GROCERY V PACIFIC COAST BISCUITrengieNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Accounting and Reporting: HTU CPA In-House Review (HCIR)Documento4 pagineFinancial Accounting and Reporting: HTU CPA In-House Review (HCIR)AnonymousNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 Int Law Reading List Sem 1 2019Documento8 pagine1 Int Law Reading List Sem 1 2019Nathan NakibingeNessuna valutazione finora

- Labor Rel Overview QsDocumento11 pagineLabor Rel Overview QsConsuelo ChavesNessuna valutazione finora

- Communism Capitalishaham Pro ConDocumento6 pagineCommunism Capitalishaham Pro ConitsaidaNessuna valutazione finora

- Taxation Law Q&A 1994-2006 PDFDocumento73 pagineTaxation Law Q&A 1994-2006 PDFClark LimNessuna valutazione finora

- Apprac Appeal From DOLEDocumento24 pagineApprac Appeal From DOLEJulius Albert SariNessuna valutazione finora

- CredTrans Set 1 CasesDocumento48 pagineCredTrans Set 1 CasesPearl EniegoNessuna valutazione finora

- 5TH Francisco V CA To People V YlaganDocumento7 pagine5TH Francisco V CA To People V YlaganBilton ChengNessuna valutazione finora

- Myreviewer Notes Property 2013 08 02 PDFDocumento17 pagineMyreviewer Notes Property 2013 08 02 PDFJade LorenzoNessuna valutazione finora

- Forgery Case DigestsDocumento4 pagineForgery Case DigestsKim Arizala100% (1)

- Ra 8371 IpraDocumento18 pagineRa 8371 IpraKirsten Denise B. Habawel-VegaNessuna valutazione finora

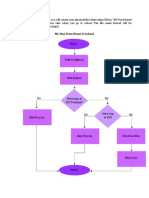

- My Way From School To Home FlowchartDocumento1 paginaMy Way From School To Home FlowchartRovie OlvidoNessuna valutazione finora

- Land Reg Laws Case DigestsDocumento11 pagineLand Reg Laws Case DigestsPaul BasillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Easements SummaryDocumento3 pagineEasements SummarybhNessuna valutazione finora

- Labor Relations Box Questions Azucena FinalDocumento27 pagineLabor Relations Box Questions Azucena FinalJessica mabungaNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurisdiction Public International LawDocumento3 pagineJurisdiction Public International LawMaria Fiona Duran MerquitaNessuna valutazione finora

- PALMA V CADocumento3 paginePALMA V CAHazel BarbaronaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sheker vs. Estate of Alice O. Sheker, G.R. No. 157912, December 13, 2007Documento2 pagineSheker vs. Estate of Alice O. Sheker, G.R. No. 157912, December 13, 2007Alena Icao-AnotadoNessuna valutazione finora

- PCGG VS SandiganbayanDocumento2 paginePCGG VS SandiganbayanHossana.contenidasNessuna valutazione finora

- Del Mar Vs PAGCORDocumento54 pagineDel Mar Vs PAGCORJane MaribojoNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 149036 - Matibag v. BenipayoDocumento38 pagineG.R. No. 149036 - Matibag v. BenipayoMA. CECILIA F FUNELASNessuna valutazione finora

- En Banc: Synopsis SynopsisDocumento33 pagineEn Banc: Synopsis SynopsisAngelika CotejoNessuna valutazione finora

- Matibag v. BenipayoDocumento3 pagineMatibag v. BenipayoFannie NagalloNessuna valutazione finora

- De Castro V JBC DigestDocumento2 pagineDe Castro V JBC DigestDean BenNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Case DigestDocumento6 pagineFinal Case DigestChardane LabisteNessuna valutazione finora

- ICJ HandbookDocumento320 pagineICJ HandbookNoel Christian Luciano100% (1)

- Tax 1 Income Tax Syllabus 2013 - LucenarioDocumento10 pagineTax 1 Income Tax Syllabus 2013 - LucenarioNoel Christian LucianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Insurance Syllabus (Dela Cerna)Documento24 pagineInsurance Syllabus (Dela Cerna)Noel Christian LucianoNessuna valutazione finora

- 11 - Persons Midterms AidDocumento26 pagine11 - Persons Midterms AidNoel Christian LucianoNessuna valutazione finora

- ProvisionsDocumento1 paginaProvisionsNoel Christian LucianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Memorial PetitionerDocumento26 pagineMemorial Petitionertanmayujjwal60Nessuna valutazione finora

- R.A 10821Documento11 pagineR.A 10821Riza Gaquit100% (1)

- Giorgio Agamben State of Exception PDF CompressDocumento52 pagineGiorgio Agamben State of Exception PDF CompressIsrael Celi ToledoNessuna valutazione finora

- Con Law OutlineDocumento3 pagineCon Law OutlineLeyana QuinteroNessuna valutazione finora

- Chairpersons Notes To The Guidelines in The Financial and Compliance Audit of COVID 19 Funds PDFDocumento3 pagineChairpersons Notes To The Guidelines in The Financial and Compliance Audit of COVID 19 Funds PDFRachelle Joy Manalo TangalinNessuna valutazione finora

- VALID EXERCISE DUTERTE Proclamation No. 475 - On The Basis of State of Calamity Under RA No. 10121 - ZABAL v. DUTERTE G.R. No. 238467, February 12, 2019Documento3 pagineVALID EXERCISE DUTERTE Proclamation No. 475 - On The Basis of State of Calamity Under RA No. 10121 - ZABAL v. DUTERTE G.R. No. 238467, February 12, 2019Ana Solito100% (1)

- Removal From Service (Special Powers) Sindh Ordinance, 2000Documento11 pagineRemoval From Service (Special Powers) Sindh Ordinance, 2000Ahmed GopangNessuna valutazione finora

- ARTICLE VI - Legislative DepartmentDocumento12 pagineARTICLE VI - Legislative DepartmentStephanie Dawn Sibi Gok-ong80% (5)

- The State of Emergency in Ethiopia: Compatibility To International Human Rights ObligationsDocumento16 pagineThe State of Emergency in Ethiopia: Compatibility To International Human Rights ObligationsBewesenu50% (2)

- GR No 187298Documento15 pagineGR No 187298Yhan AberdeNessuna valutazione finora

- State Emergency - Article 356Documento4 pagineState Emergency - Article 356Lukman KmNessuna valutazione finora

- Constitutional Law 1: (Notes and Cases)Documento15 pagineConstitutional Law 1: (Notes and Cases)Mary Ann AmbitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dr. Ambedkar With The Simon Commission Preface PDFDocumento75 pagineDr. Ambedkar With The Simon Commission Preface PDFVeeramani ManiNessuna valutazione finora

- Gonzales v. Hechanova, G.R. No. L-21897Documento8 pagineGonzales v. Hechanova, G.R. No. L-21897Daryl CruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Emergency Powers & THE Bayanihan ACTDocumento4 pagineEmergency Powers & THE Bayanihan ACTKristinaCuetoNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 David V ArroyoDocumento99 pagine3 David V ArroyoMelchizedek Beton OmandamNessuna valutazione finora

- Rodriguez V Gella (Case Digest)Documento2 pagineRodriguez V Gella (Case Digest)Christopher Dale WeigelNessuna valutazione finora

- Article 360 of Indian Constitution - An AnalysisDocumento9 pagineArticle 360 of Indian Constitution - An AnalysisIJRASETPublicationsNessuna valutazione finora

- Agamben - State of Exception - Full PDFDocumento16 pagineAgamben - State of Exception - Full PDFBakos BenceNessuna valutazione finora

- Se Jhoojhta Haryana), Written by Annapurna Sagar, Originally Published by The RashtriyaDocumento16 pagineSe Jhoojhta Haryana), Written by Annapurna Sagar, Originally Published by The RashtriyaNikihil MalikNessuna valutazione finora

- FMP - Written Submissions - FMP in Anuradha Bhasin v. UoIDocumento18 pagineFMP - Written Submissions - FMP in Anuradha Bhasin v. UoIanushka srivastavaNessuna valutazione finora

- Calamity Fund Guidelines PDFDocumento41 pagineCalamity Fund Guidelines PDFMylyn Cajucom100% (4)

- The Derogation of Human RightsDocumento9 pagineThe Derogation of Human RightsryanrailsNessuna valutazione finora

- LegPhilo Finals DigestDocumento60 pagineLegPhilo Finals DigestJam100% (1)

- 03 Poli (Separation & Delegation of Powers) - Atty. FallerDocumento5 pagine03 Poli (Separation & Delegation of Powers) - Atty. FallerCleo ChingNessuna valutazione finora

- Travis County Declaration of DisasterDocumento2 pagineTravis County Declaration of DisasterCBS Austin WebteamNessuna valutazione finora

- David Vs Macapagal ArroyoDocumento5 pagineDavid Vs Macapagal ArroyoAbbyElbamboNessuna valutazione finora

- Phil. Global Communications Vs RelovaDocumento4 paginePhil. Global Communications Vs RelovaJonjon BeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Eighteenth Amendment NewDocumento29 pagineEighteenth Amendment NewRabia JavedNessuna valutazione finora

- Emergencies Act Inquiry Final Report Vol. 2Documento403 pagineEmergencies Act Inquiry Final Report Vol. 2National PostNessuna valutazione finora