Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

TITLE: GESTURE DRAWING: The Essence of Capturing The Moment As A Tool For Extended Investigation

Caricato da

Lesson Study ProjectDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

TITLE: GESTURE DRAWING: The Essence of Capturing The Moment As A Tool For Extended Investigation

Caricato da

Lesson Study ProjectCopyright:

Formati disponibili

TITLE: GESTURE DRAWING: The Essence of Capturing the Moment as a Tool for Extended Investigation

BACKGROUND: When enrolling in Drawing II the University of Wisconsin--Stevens Point art and design students have already covered the basics of drawing. This second drawing class is then geared for developing conceptual ideas within an exploration of color media. However, faculty had noticed that the building block of gesture was applied inconsistently within the Drawing II class. This assignment was to reintroduce the student to gesture in a different way: building multiple gestural images on the same page and relating those images through color and mark-making utilizing the entire picture plane. The assignment emphasizes the importance of gesture and the application gesture has in drawing and painting development.

AUTHORS: Diane Canfield Bywaters, Professor, Susan Morrison, Professor Sheila Sullivan, Associate Lecturer

COURSE:

ART 104. Drawing II. 3 cr. Foundations drawing using a variety of media and approaches with emphasis on conceptual development and color theory/application. Prereq: 103 [Drawing I].

GESTURE DRAWING: STEPS OF THE LESSON 1. Students need several sheets of paper, minimum 18 x 24 inches, ready at drawing board, preferably at an easel. One sheet is taped to board, extra tape available. Several sticks of soft, heavy charcoal (Alphacolor charcoal). All students should be standing for this exercise. 2. Teacher demonstrates with her/his own clothed body what fast poses entail but moving in a slow motion dance-like succession of positions and explains: a) main lines of force in body b) weight bearing leg c) center of gravity d) overall distances between parts of body -- how to see across form and measure form to form e) sense of stress/energy required to take poses -- can ask the class to take a pose at this point -- to realize this is a high energy, muscle tiring exercise which requires full effort on part of those drawing 3. Undraped Model or draped model takes podium. Consult with model whether teacher will call 10 second shifts or model will just move in approximately that amount of time. 4. Model takes pose. Before students draw, teacher draws in air in front of model the entire life-size movement. Teacher uses her/his entire arm and body to demonstrate how quickly -- in less than 10 seconds -- the entire pose can be captured. This quick demo shows how fast, broad based marks are the only way to capture this pose in this short amount of time. 5. Recommend putting on a fast paces music CD at this time. 6. Begin 7. Do not waver on the 10 second time frame. Do this for 10 minutes. Teacher circles room and demos on paper if necessary. All students should be standing. More paper is made available as needed. Many drawings can be done one over the other until page is a web of lines. 8. Do not allow stick figures. Emphasize: a) initial line of force of pose b) scribbling marks that "discover shape" c) use groin and torso as center point and work out d) lift charcoal on and off paper -- skip around page and find relationships

9. Repeat the concepts that it is not what the form looks like but rather what the form is doing that is the goal of the assignment. 10. After this 10 minute exercise -- which is a good exercise before any life drawing session -- the concept of gesture can be utilized in a number of ways:

a) Display drawings as is. Discuss the work of Susan Rothenberg and how this relates. b) Cut up drawings and use in collage c) Do quick gestures on paper, overlapping but not too dense. Erase as able -- charcoal will leave marks. These marks become a ground -- "pentamento" -- for a longer drawing. Some of the ground marks surprisingly enhance the marks of the final work. d) Do quick gestures in vine charcoal before any longer drawing or painting to capture the movement and avoid stiff, labored figures. e) Use gesture drawing as basis of longer realistic or abstract image adding color and other media as desired.

What results have emerged? LEARNING GOALS Loosen up Full body motion to move drawing hand (versus wrist action) Quick visualization Trust Understanding that gesture is an unlimited root of extended drawing

THE STUDY Steps for classroom assignment are located on p. 1-2. Discussion: Artists such as Susan Rothenberg, Jim Dine, Rembrandt, Toulouse Lautrec can be used to encourage dialogue and visual stimulus to increase understanding. Revisions: Add element of famous artists prior to assignment versus later in critique. Force a faster time frame for longer period of time. Individual faculty participants strongly felt differently on time frames extending from 10 seconds to one minute. We realized in discussion how one concept such gesture drawing can be interpreted in various manners, each feeling they achieve success.

What resources / references have you found helpful? Handouts (2): Handout One. Emeritus Dr. Walter Ball, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, Illinois. This handout was distributed to Sheila Sullivan during graduate school (Northern Illinois University in DeKalb) mentor, Dr. Walter Ball (located p. 7-9.) Handout Two. Associate Lecturer Sheila Sullivan's adaptation of this drawing assignment (located on last page.)

What was your approach and/or what evidence have you gathered? APPROACH Open minded, high energy, experimental and process oriented, for a kinesthetic experiential drawing. FINDINGS The students resist this risk taking; and uncontrolled non-representational "scribbling". However, once the student succeeds at this approach there is a confidence, and willingness to "go with the flow" and to let the picture grow from the page rather than be dictated by a mental construct.

Students have exhibited works created in this and related assignments in the UWSP Juried Annual Art Foundation Exhibition (juried by an outside judge). In addition, the faculty who are using this assignment and related assignments consistently receive excellent faculty evaluations, and student comments related in evaluations are consistently positive. Initially the assignment was taught without the use of master examples presented in the classroom and handouts, our findings indicate that this added information enriches the outcome. To our surprise, the act of creating the video segment of this project also enriched the experience of the students, and could be a teaching and learning opportunity for further study. The video was produced by class member: Noah Martin. The final video was also presented as a culmination activity for the class.

Examples of student work: Numerous figure examples are on the two-part video. If a figure model is not available, the students' hands and feet can be used for a similar assignment. Below are two examples of the assignment with hands and feet created in Professor Susan Morrison's classroom. These drawings were created in pastel on Kraft brown paper with a limited palette of primary colors.

VIDEO: Gesture Drawing with Professor Bywaters Part One VIDEO: Gesture Drawing with Professor Bywaters Part Two

Student drawing example from class, created with a limited palette of primary colors with brown paper.

Another student example of hands and feet from Professor Morrisons class.

HANDOUT ONE PAINTING ASSIGNMENT III, DEMONSTRATION/DISCUSSION SUMMARY

GESTURE/FIGURE: Gesture is the action of a figure, shape or form. Gesture indicates what the figure is doing. Included are the figure's body language, its animations, exaggerations and reductions of body features as well as its movement. Gesture can, through body language and implied movement, convey internal attitudes of the figure. The intent of the gesture in drawing/painting is to characterize the action of the figure, rather than to represent its appearance or surface volumes and contours. What the form is doing is more important than what it looks like. Painters often use the gesture of the figure as a vehicle for the overt expression of ideas. In using gestures, the action and animation of the figure are indispensable to the over all expressiveness of the idea of the work. The immediate clarity of the gesture, with its coherence and impact are vital to its effectiveness. Gesture in drawing/painting is intended to identify alternative attitudes to those oriented mostly to object representation or to techniques. The technical finesse of representation is not our immediate concern. Our emphasis on gesture involves the animated simplification of figurative forms through large simplified or obvious brush calligraphy, on the one hand, and the development of its thematic attributes, ideas or attitudes on the other. The following are three basic aspects of gesture and their uses. A. The action of a figure, or what it is doing physically as gestures (learning, falling, climbing, pushing, swinging, etc.), suggests activity that conveys internal attitudes that are evoked by the gesture of the subject. Thus the figurative gesture is a vehicle which transmits ideas to the viewers much like stage actors use body language, animation and action to convey ideas without the spoken language. EXAMPLES (sizes are in inches): Guido da Siena, Reliquary Shutters, egg tempra, 1255-60. Giotto, Ecstasy of St. Francis, fresco, 1296-97 Michelangelo, Creation of Adam, fresco, 1509-10. Libian Sibyl, fresco, 1508-12 Creation of Worlds, fresco, 1508-12 Peter Paul Rubens, Horrors of War, oil, 1638 Debarkation at Marseilles, 156 x 98, oil , 1638 Detail 1, Detail 2. Honore Daumier, Three Lawyers in Conversation, oil, 1843-48 Print Collector, oil, 13-3/8 x 10-1/4, c. 1960. The Connoisseurs, charcoal/pastel/watercolor/pencil, 10-1/4 x 8, 1862-63.

Uprising, oil, 54 x 44, 1860. Circus Parade, ink line/wash, c. 1850-60 Reginald Marsh, High Yaller, oil, 23-1/2 x 17-1/2, 1934. Edvard Munch, Puberty, oil, 59-5/8 x 43-1/4, 1895. The Scream, oil/casein/pastel, 36 x 29, 1893. Madonna, lithograph, 24 x 17-1/2, 1895. George Bellows, Stag at Sharkeys, oil, 36-1/4 x 48-14, 1908-09. B. Calligraphy of the brush stroke, like handwritten script, registers the hand, arm and body movements that create the marks. The stroke may thus be used by itself, without images, or again used to support the characterization of the figure's action. EXAMPLES: Richard Diebenkorn, Seated Nude, Black Background, oil, 80 x 50, 1961. Emile Nolde, The Dance Round the Golden Calf, oil, 34-5/8 x 41-5/8, 1910. Chaim Soutine, Female Nude, oil, 18-1/8 x 10-5/8, 1933. Woman Bathing, oil, 21-3/8 x 24-3/8, 1929. Jackson Pollock. Number 3, oil, 56 x 24, 1951. Number 1, oil, 68 x 104, 1948. Franz Klein, Crosstown, oil, 48 x 65, 1955. White Forms, oil, 74 x 50, 1955. William DeKooning, Woman I, oil, 75-5/8 x 58, 1952. The Visit, oil, 60 x 48, 1966-67. (dancing figure) Door to the River, oil, 80 x 70, 1960. C. Abstract, non-representational, or essentially visual (pictorial) action of a form, which immediately evokes a sense of action, is another aspect of gesture. In its more pure form the abstract gesture bears no debt for its origin to subject matter or kinetic calligraphy of gestural hand/arm movements or strokes. EXAMPLES: Henri Matisse, Souvenir of Oceania, gouache and crayon on cut and pasted paper, 112-3/4 x 112-3/4, 1953. Snail, gouache/cut and pasted paper, 112-3/4 x 113, 1953. Woman with Green Line, oil, 16 x 13, 1905. Larry Poons, Han-san Cadence, acrylic and fabric dye, 1963. Morris Louis, Gamma Delta, acrylic, c. 1961. Aleph Series II, oil, 78 x 106, 1960. Mathew Smith, Nude, Frizroy Street, No. 1, oil, 34 x 30, 1916 The assignment is to complete 6 to 8 oil sketches on "oak tag" paper (24 x 36) using the instructions given on gestures, followed by the completion of a painting (34 x 40) during one class session.

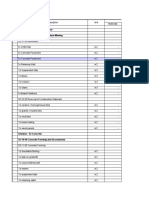

No line is to be used for any phase of the assignment, in either the oil sketches on paper or the painting on canvas. Outlined edges that behave as penciled line flatten forms and work against the development of gesture by isolating or "localizing" the form. Even when outline is later overpainted the isolating format remaining devastates actions of both calligraphic strokes and the figure. Instead of line use a wide brushstroke through the axis of all major forms of the figure first, leaving the brush on the surface for as much stroke extension as possible. You will find that calligraphic strokes shaped to characterize action tend to form their own shapes as a natural result of the process. Background spaces, likewise, are to be painted with similar action strokes that start at the axis of the shape. Use dull light colors to lay out the axis of the figure action. Follow through with the one light and one dark set of colors as described during the assignment presentation. Your goal is to quickly characterize the stance and implied actions of the pose and to relate these characteristics to background forms as well as figurative areas of the sketches and painting. Passages that include both figurative and background areas should sustain a common stylistic treatment and be in proportion to the full picture plane. Colors and tones used tin the background areas should also be used in the figurative areas and vice versa. This contributes to the cohesiveness of the picture plane. As with the modulation assignment, you must remain acutely aware of the tonality of all colors to do well in this assignment. The oil sketches are to be completed during the first two sessions. The oil painting should ideally be completed in one session (one day). Special materials needed are (sizes are in inches): 1 stretched canvas, approximately 40 x 34 8 sheets of oak tag paper, 36 x 24 1-3 bristle brushes for oil, 2 x 1-1/2 wide (hardware store). Pre-mix three light colors of the same value and three dark colors of the same value. Other colors may be mixed as needed. Dull to bright and hue variations should be available when you start the sketches. Reference: Kimon Nicholaids, The Natural Way to Draw, pp. 188-221. Record of model use dates: Oil sketches on oak tag paper. Oil sketches on oak tag paper. Oil on canvas, one pose, full period. Oil on canvas, one pose, full period. (If needed)

HANDOUT TWO GESTURE AND TONAL PROGRESSION

General Notes: 1) Each step of the following progression is intended to include and be based on all preceding steps. Complete each step layer by layer before going on to the next step. View the work on the entire picture plane rather than in segments. 2) Technical completion, in itself, is not the main criterion by which your work will be judged. What is important is the full-page effect of the drawing's expressive qualities, achieved by the process of working through the layers in the following stages. 3) Use charcoal. Students in 236 may use other media (washes, paint, pastels, etc.). Step One: With charcoal, lightly indicate the gesture and placement of the figure on the picture plane. Start with the figure's axis, and make successive passes through the figure to rough out the form, improve its animation, body language, and proportion. Note: 1) Gesture is the action of the form, not its surface, edge, or likeness. 2) Proportion, while important, is secondary to the action. Step Two: Work dark tone over light to link, reduce and shape the tone inside the figure. Note: Outline is counter-productive.

Step Three: Emphasize the tonal relationships between positive and negative areas. Use grouped tones across edges of images to link areas into "passages" of light or dark that relate positive to negative, or positive to positive segments of the picture plane. This creates a range of sizes of these passages on the picture plane. Note: 1) In this stage, develop the background and the grouping of tones, extending the grouping into the background space. 2) Use a kneaded eraser to improve tonal relationships among light areas. Once you have established tonal relationships, you may strengthen them with white chalk, thus achieving better control of value nuances in the light areas.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Art and Math Lesson Plan 2Documento4 pagineArt and Math Lesson Plan 2api-311011037Nessuna valutazione finora

- Art 10 - Shattered Image Unit PlanDocumento8 pagineArt 10 - Shattered Image Unit Planapi-451208805Nessuna valutazione finora

- Artii How To Draw A FacewordDocumento2 pagineArtii How To Draw A Facewordapi-217117343Nessuna valutazione finora

- Yr7 Visualarts LessonplanDocumento7 pagineYr7 Visualarts Lessonplanapi-219261538Nessuna valutazione finora

- Tiered Lesson Educ GDocumento7 pagineTiered Lesson Educ Gapi-427675209Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sap Week 8Documento20 pagineSap Week 8api-332477452Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan 1 - Falling Back Into Space 2Documento3 pagineLesson Plan 1 - Falling Back Into Space 2api-242370085Nessuna valutazione finora

- Art TechniquesDocumento42 pagineArt Techniquesedlyntonic2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan MorrisseauDocumento7 pagineLesson Plan Morrisseauapi-390372644Nessuna valutazione finora

- Art Ed Lesson Plan Draft 2Documento4 pagineArt Ed Lesson Plan Draft 2api-528624842Nessuna valutazione finora

- Synthesis and ConclusionDocumento5 pagineSynthesis and Conclusionapi-318316910Nessuna valutazione finora

- Measuring For The Art Show - Day 1Documento6 pagineMeasuring For The Art Show - Day 1api-283081427Nessuna valutazione finora

- CW Grade 7 Module 1Documento15 pagineCW Grade 7 Module 1ROSALIE MEJIA100% (1)

- Analyzing A Photograph - A How-To GuideDocumento3 pagineAnalyzing A Photograph - A How-To GuideRogerio Duarte Do Pateo Guarani KaiowáNessuna valutazione finora

- Jessica Woodley c1 - Visual Arts 4035 Lesson PlanDocumento8 pagineJessica Woodley c1 - Visual Arts 4035 Lesson Planapi-395233182Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan (Cone of Experience)Documento5 pagineLesson Plan (Cone of Experience)Katrina Rempillo69% (13)

- Digital PortfolioDocumento184 pagineDigital Portfolioapi-298775308Nessuna valutazione finora

- Betterlesson - Introduction To Fractions A Concrete ExperienceDocumento4 pagineBetterlesson - Introduction To Fractions A Concrete Experienceapi-621042699Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lessonplan 2Documento4 pagineLessonplan 2api-310441633Nessuna valutazione finora

- Drama SowDocumento4 pagineDrama Sowsmaranda_nicolauNessuna valutazione finora

- Dance Math Lesson PerimterDocumento3 pagineDance Math Lesson Perimterapi-402266774Nessuna valutazione finora

- Curriculum Document and Powerpoint/Prezi Framework:: 1. Conceptual StructureDocumento5 pagineCurriculum Document and Powerpoint/Prezi Framework:: 1. Conceptual Structureapi-289511293Nessuna valutazione finora

- Gesture Assignment-1Documento2 pagineGesture Assignment-1jenna ibanezNessuna valutazione finora

- Semester Overview Arts Visual Arts Year 3 2012Documento2 pagineSemester Overview Arts Visual Arts Year 3 2012api-185034533Nessuna valutazione finora

- Art FinalDocumento8 pagineArt Finalapi-241170479Nessuna valutazione finora

- Art 2 Unit 4Documento9 pagineArt 2 Unit 4api-264152935Nessuna valutazione finora

- I. Lesson Number, Grade Levels, Title, and DurationDocumento5 pagineI. Lesson Number, Grade Levels, Title, and Durationapi-309787871Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson ThreeDocumento8 pagineLesson Threeapi-355030109Nessuna valutazione finora

- Micro-Teach - Ed 3601 - C & I For Art Majors Jesse & Rachael - Screen Printing (Grade 11)Documento21 pagineMicro-Teach - Ed 3601 - C & I For Art Majors Jesse & Rachael - Screen Printing (Grade 11)api-296545006Nessuna valutazione finora

- Activity Plan and Justification 2 - Vocabulary InstructionDocumento5 pagineActivity Plan and Justification 2 - Vocabulary Instructionapi-605907903Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mapeh: Music - Arts - Physical Education - HealthDocumento15 pagineMapeh: Music - Arts - Physical Education - HealthRhona Angela Cruz100% (1)

- Perspective Elijah MintonDocumento4 paginePerspective Elijah MintonREBUSORA BTLED IANessuna valutazione finora

- Abstrakt Mahler LehrenDocumento19 pagineAbstrakt Mahler LehrenAske OlsenNessuna valutazione finora

- Between The Lines: Experiencing Space Through Dance: DR Rachel Sara, Senior LecturerDocumento11 pagineBetween The Lines: Experiencing Space Through Dance: DR Rachel Sara, Senior LecturerJavier Villar MoralesNessuna valutazione finora

- TVL Illu11 Q3 M2Documento13 pagineTVL Illu11 Q3 M2Prince Jariz SalonoyNessuna valutazione finora

- Arts Grade 10 - M1-L1Documento15 pagineArts Grade 10 - M1-L1Rhona Angela Cruz100% (1)

- PencilSketchDrawingGheno EbookDocumento14 paginePencilSketchDrawingGheno EbookKojak Verduzco83% (6)

- Area Triangle Circles Unit Lesson Plan 3Documento4 pagineArea Triangle Circles Unit Lesson Plan 3api-671457606Nessuna valutazione finora

- Art-Lm 2Documento17 pagineArt-Lm 2Josephine SarvidaNessuna valutazione finora

- Vts Video Analysis Worksheet Cavan WrobleskiDocumento2 pagineVts Video Analysis Worksheet Cavan Wrobleskiapi-739054154Nessuna valutazione finora

- CT Reflection 2Documento7 pagineCT Reflection 2api-340158983Nessuna valutazione finora

- Primary and Secondary Colors Lesson PlanDocumento17 paginePrimary and Secondary Colors Lesson PlanAnonymous AfPih7100% (4)

- Becky Drawing UnitDocumento5 pagineBecky Drawing Unitapi-273390483Nessuna valutazione finora

- Grid DrawingDocumento5 pagineGrid Drawingapi-29642352150% (2)

- Sîrbu Iustina Rebeca Lma2 Ger. MetodicaDocumento2 pagineSîrbu Iustina Rebeca Lma2 Ger. MetodicaRebecca SîrbuNessuna valutazione finora

- Drawing Outside The Box: Three Lesson Plan: DrawingDocumento19 pagineDrawing Outside The Box: Three Lesson Plan: Drawingapi-273259841Nessuna valutazione finora

- Grade 1 3 Art Lesson1Documento2 pagineGrade 1 3 Art Lesson1api-237688616Nessuna valutazione finora

- INSTRUCTOR: Kristin Richins DATE: 3/24/2012 COURSE TITLE: Theatre Methods Lesson #: 7 UNIT: History in Plays and Musicals Specific TopicDocumento3 pagineINSTRUCTOR: Kristin Richins DATE: 3/24/2012 COURSE TITLE: Theatre Methods Lesson #: 7 UNIT: History in Plays and Musicals Specific TopicKristin RichinsNessuna valutazione finora

- Visual Art SS 1 Second TermDocumento17 pagineVisual Art SS 1 Second Termpalmer okiemuteNessuna valutazione finora

- Covid-19 Art Lesson UbdDocumento3 pagineCovid-19 Art Lesson Ubdapi-467549012Nessuna valutazione finora

- LP ConesDocumento6 pagineLP ConesNelvic Parohinog PanuncialesNessuna valutazione finora

- 2nd GradeDocumento25 pagine2nd Gradeapi-454718946Nessuna valutazione finora

- Measuring For The Art Show - Day 2Documento6 pagineMeasuring For The Art Show - Day 2api-283081427Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Elements of Drama: SpaceDocumento4 pagineThe Elements of Drama: SpaceDessa Canada HongoyNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan: Step 1: Curriculum ConnectionsDocumento9 pagineLesson Plan: Step 1: Curriculum Connectionsapi-395300283Nessuna valutazione finora

- Visual Art Lesson PlanDocumento5 pagineVisual Art Lesson Planapi-329451598Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hanson Lesson Plan Spring 2022Documento8 pagineHanson Lesson Plan Spring 2022api-603945516Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Study Project Showcase Catl@uwlax - EduDocumento10 pagineLesson Study Project Showcase Catl@uwlax - EduLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- Part I: Background: Lesson Study: Developing Students' Thought Processes For Choosing Appropriate Statistical MethodsDocumento14 paginePart I: Background: Lesson Study: Developing Students' Thought Processes For Choosing Appropriate Statistical MethodsLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- Mweege@uwlax - Edu Astaffaroni@uwlax - EduDocumento13 pagineMweege@uwlax - Edu Astaffaroni@uwlax - EduLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento12 pagineUntitledLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento12 pagineUntitledLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Lesson Study Guidelines: Part I: BackgroundDocumento11 pagineFinal Lesson Study Guidelines: Part I: BackgroundLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento8 pagineUntitledLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento27 pagineUntitledLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento6 pagineUntitledLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Study Final Report Template: RD TH THDocumento6 pagineLesson Study Final Report Template: RD TH THLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- Part I: Background TitleDocumento13 paginePart I: Background TitleLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento10 pagineUntitledLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento11 pagineUntitledLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- Galbrait - Anne@uwlax - Edu: Lesson Study Final Report (Short Form) Title: Team MembersDocumento5 pagineGalbrait - Anne@uwlax - Edu: Lesson Study Final Report (Short Form) Title: Team MembersLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento4 pagineUntitledLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento3 pagineUntitledLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Study Final Report TemplateDocumento6 pagineLesson Study Final Report TemplateLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento6 pagineUntitledLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento27 pagineUntitledLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento8 pagineUntitledLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- Wardj@uwp - Edu: Learning Goals: Students Will Gain A Deeper Understanding of Water Resource Issues, The Importance ofDocumento5 pagineWardj@uwp - Edu: Learning Goals: Students Will Gain A Deeper Understanding of Water Resource Issues, The Importance ofLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento20 pagineUntitledLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento7 pagineUntitledLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Study Final Report Part I: Background Lesson TopicDocumento9 pagineLesson Study Final Report Part I: Background Lesson TopicLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento16 pagineUntitledLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- Interdisciplinary Lesson Study: Communication Studies and Library Information Literacy ProgramDocumento12 pagineInterdisciplinary Lesson Study: Communication Studies and Library Information Literacy ProgramLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento5 pagineUntitledLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento19 pagineUntitledLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Study Final Report: Part I: Background Title: AuthorsDocumento28 pagineLesson Study Final Report: Part I: Background Title: AuthorsLesson Study ProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- Sat Practice Test 6 Digital 1Documento56 pagineSat Practice Test 6 Digital 1liliNessuna valutazione finora

- Galvanized Steel Inspection GuideDocumento20 pagineGalvanized Steel Inspection GuidePham Ngoc Khan100% (2)

- Michaël BorremansDocumento3 pagineMichaël BorremansE EstebanNessuna valutazione finora

- Dyeing of Synthetic FibersDocumento15 pagineDyeing of Synthetic FibersHaqiqat AliNessuna valutazione finora

- OCKMAN J - Form Without UtopiaDocumento9 pagineOCKMAN J - Form Without UtopiaSérgio Padrão Fernandes100% (1)

- Karacho's Karakami Woodblock-Printed Paper01Documento1 paginaKaracho's Karakami Woodblock-Printed Paper01Bil AndersenNessuna valutazione finora

- Individual PresentationDocumento6 pagineIndividual PresentationPatricia ByunNessuna valutazione finora

- GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LogDocumento3 pagineGRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Logecardnyl25Nessuna valutazione finora

- Pantone Plus Color Bridge CMYKDocumento117 paginePantone Plus Color Bridge CMYKwyllow_2367% (12)

- Music - Summative TestDocumento5 pagineMusic - Summative TestJessa Banawan EdulanNessuna valutazione finora

- Dressmaking Learning Module PDFDocumento109 pagineDressmaking Learning Module PDFHazel Villacorta KimKwonNessuna valutazione finora

- Fundraiser To Keep Teen's Memory Alive: Inside This IssueDocumento16 pagineFundraiser To Keep Teen's Memory Alive: Inside This IssueelauwitNessuna valutazione finora

- Amazing Photoshop Light Effect in 10 Steps - Abduzeedo - Graphic Design Inspiration and Photoshop TutorialsDocumento15 pagineAmazing Photoshop Light Effect in 10 Steps - Abduzeedo - Graphic Design Inspiration and Photoshop TutorialsPedro PiresNessuna valutazione finora

- Tle - Week2 - Market Trends and Customer's Preference of ProductsDocumento35 pagineTle - Week2 - Market Trends and Customer's Preference of ProductsMarlene Tagavilla-Felipe DiculenNessuna valutazione finora

- Aircraft MarkingsDocumento160 pagineAircraft MarkingsAerokosmonautika92% (12)

- Portrait Artists - CotesDocumento125 paginePortrait Artists - CotesThe 18th Century Material Culture Resource Center100% (1)

- Enlarger Experiments To TryDocumento7 pagineEnlarger Experiments To Tryrla97623Nessuna valutazione finora

- MethamphetazineDocumento6 pagineMethamphetazineMichael_Lee_RobertsNessuna valutazione finora

- Guideline Document For ID Card Photo Shoot Annexure BDocumento4 pagineGuideline Document For ID Card Photo Shoot Annexure BOmkar RaneNessuna valutazione finora

- Why Photography Matters As Art As Never Before byDocumento9 pagineWhy Photography Matters As Art As Never Before byRaluca-GabrielaNessuna valutazione finora

- 3d Drawing and Optical IllusionsDocumento70 pagine3d Drawing and Optical IllusionsValter Carvalho100% (4)

- Carboguard 60 PDSDocumento2 pagineCarboguard 60 PDSsalamrefigh0% (1)

- Heidegger, Adorno, and The Persistence of RomanticismDocumento11 pagineHeidegger, Adorno, and The Persistence of RomanticismcjlassNessuna valutazione finora

- Classified: Your Local MarketplaceDocumento5 pagineClassified: Your Local MarketplaceDigital MediaNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit Rates and Cost Per ItemDocumento213 pagineUnit Rates and Cost Per ItemDesiree Vera GrauelNessuna valutazione finora

- Luxaprime1501 Etch PrimerDocumento2 pagineLuxaprime1501 Etch PrimerGurdeep Sungh AroraNessuna valutazione finora

- Edvard Munch: Behind The ScreamDocumento391 pagineEdvard Munch: Behind The Screamdavidlightman100% (8)

- Liquid Embroidery NotesDocumento5 pagineLiquid Embroidery NotesAmrutha InstitutionsNessuna valutazione finora

- The Folk BoxDocumento33 pagineThe Folk BoxGenserviaNessuna valutazione finora