Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Press Release 2011 VHMR

Caricato da

schreurs1176Descrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Press Release 2011 VHMR

Caricato da

schreurs1176Copyright:

Formati disponibili

Press release Ancient migration in the Indian Ocean - New perspectives in the ancient peopling of Madagascar.

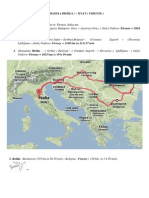

Although the island of Madagascar is only separated by about 400 km from the African coast, it was one of the last large islands in the world to be permanently settled by humans. How, when and by whom Madagascar was settled, however, remains poorly known. Traces of human occupation dating back to the first millennium have been identified along parts of the Malagasy coast and several lines of evidence (e.g., linguistic, anthropologic, genetic) indicate that the ancestors of the Malagasy came from different parts of the shores of the Indian Ocean including Indonesia, East Africa and the Near East. A re-evaluation of existing archaeological documentation and artifacts now suggests that there might also be a Chinese contribution in Malagasy ancestry. Archaeological excavations in northern Madagascar in the early 20th century has revealed the presence of a former prosperous civilization that is referred to by archaeologists as the Rasikajy civilization. The most striking evidence for this civilization came from excavations at a necropolis near the coastal town of Vohemar, where more than 600 tombs containing spectacular objects were unearthed in the early 1940s by a French district administrator (Gaudebout) and a French priest/pasteur (Vernier). The burial objects in the tombs included Chinese ceramics, iron weapons, silver and gold jewelry, glassware, bronze mirrors, shell spoons and objects carved out of soapstone such as tripod vessels and incense burners. Some of the burial objects were clearly imported (e.g. Chinese ceramics, glassware), whereas others were made in Madagascar (e.g. soapstone objects, iron objects, shell spoons and possibly gold jewelry). The soapstone objects found in the tombs and at other archaeological sites were produced locally from soapstone mined at quarries that have been identified in northern Madagascar and eastern Madagascar (region of Mananjary). The French archaeologist Verin proposed in the 1980s that the prosperity of the Rasikajy was linked to their production of and trade in soapstone objects (Verin, 1986), which have not only been found in Madagascar, but also in the Comoros and eastern Africa suggesting an active engagement in the western Indian Ocean trade network. Little is known about the origin of the Rasikajy civilization and how and when they first arrived in Madagascar. Previous studies considered the Rasikajy civilization to be the result of biological and cultural intermingling between Islamized immigrants and local coastal people (Verin, 1986). A re-evaluation of the pottery in the tombs of Vohemar indicates that the majority of Chinese ceramics dates from the 15th and first half of the 16th century with some dating back to the 14th century or earlier (Monique Crick, Fondation Bauer, Geneva, 2010, pers. comm.). A single carbon dating on bones from a skeleton excavated at the necropolis of Vohemar has yielded an age of 760 60 (Vernier & Millot, 1971), i.e. around 1200 CE. Soapstone objects have been found in many sites that have been dated between 10th and 16th century. These data suggest that the Rasikajy were already present in Madagascar prior to the arrival of the Europeans in the western Indian Ocean in the late 15th /early 16th century. Our recent comparative analysis of burial objects at Vohemar shows that soapstone tripod vessels produced in Madagascar exhibit remarkable resemblances to ancient Chinese bronze ritual vessels found in tombs in China over several millennia (e.g. Zhou and Han dynasties,

1046 BCE 220 CE). During the Song and Yuan dynasties (10th-14th century) it was en vogue in SE-China to produce archaic tripod vessels modeled on burial ware from earlier dynasties. The objects encountered in the tombs at Vohemar and their positions with respect to the body indicate that the Rasikajy practiced burial rites similar to those practiced in China in the past. In both places, food utensils (bowls, dishes, spoons, plates, vessels) were placed in graves to provide the deceased with food for the afterlife, whereas bronze mirrors were placed in front of the deceased persons forehead to provide light in the afterlife. Pierced circular soapstone disks found at Vohemar possibly represent bi-disks, which were placed in graves in China to accompany the deceased on his voyage to the afterlife. The elephant en pierre or sanglier en pierre (vatomasina / vatolambo) found along the east coast at Ambohitsara (North of Mananjary) is also made of soapstone and shows similarities to Chinese ritual vessels or stone figures placed along alleys leading towards Chinese mausoleums. Our re-evaluation of existing archaeological documentation suggests that pre-European communities with Chinese roots might have been present in Madagascar and participated in the Indian Ocean trade network. The demise of these communities seems to have occurred in the second half of the 16th century when production of soapstone objects ceased. It still is unclear why this occurred. As the east coast of Madagascar is extremely vulnerable to tropical cyclones, tsunamis, river flooding and coastal erosion, it cannot be excluded that natural hazards played a role in the demise of the Rasikajy civilization and the abandonment of the necropolis at Vohemar. Since the 1950s no archaeological research has been carried out at the necropolis of Vohemar. During the last three years, however, archaeological research has been conducted in the surroundings of Vohemar as part of the Institut de Civilisations/Muse dArt et dArchologie (University of Antananarivo) research programme on river estuaries. We emphasize that further archaeological excavations on pre-European sites are necessary to determine the nature of these communities and to corroborate our ideas. Over the last decades, many new or improved research tools and methods have become available that could be helpful in shedding more light on the origins of the Rasikajy. Ancient DNA, stable isotope and radiocarbon dating studies on new and existing material from burial sites in Madagascar can provide further insights into the geographical origins of the pre-European communities and when and how they lived. The ancestral relations of present-day communities claiming ancestral links to the Rasikajy can be investigated through a linguistic, historical, social and cultural anthropological study in which the socio-historical configurations of the communities and particularly their burial objects and rites can be compared with similar artifacts and burial practices within Madagascar, China and Southeast Asia. Geomorphological studies of coastal sites in Madagascar can help in clarifying whether natural hazards contributed to the demise of the Rasikajy civilization, and provenance studies of soapstone objects found in the western Indian Ocean can reveal the extent of the trading network of the Rasikajy. This is just a selection of research avenues that can be employed to investigate the fascinating and largely still enigmatic history of settlement of Madagascar. Antananarivo, 13 January 2011 Chantal Radimilahy (Institut de Civilisations/Muse dArt et dArchologie de lUniversit dAntananarivo, Antananarivo, Madagascar) and Guido Schreurs (Universit de Berne, Suisse).

References Vernier E. et J. Millot. 1971. Archologie malgache Comptoirs musulmans. Catalogues du Muse de lHomme, Srie F - Madagascar. Vrin P. 1986. The History of Civilisation in North Madagascar. Rotterdam, Balkema.

Photo of tripod vessel found at Vohemar ((Vernier & Millot, 1971)

Photo of the statue vatomasina at Ambohitsara A selection of objects from past excavations at Vohemar can be viewed online at www.quaibranly.fr _________________________________________________________

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Beber Calendar PDFDocumento30 pagineBeber Calendar PDFsonetlessNessuna valutazione finora

- Bailey 97 V 1Documento401 pagineBailey 97 V 1xdboy2006Nessuna valutazione finora

- And The Oscar Goes ToDocumento4 pagineAnd The Oscar Goes ToDiego BoytrönNessuna valutazione finora

- The Collection of Suzanne Saperstein Fleur de Lys: Beverly Hills, California - NY, 19 April 2012Documento2 pagineThe Collection of Suzanne Saperstein Fleur de Lys: Beverly Hills, California - NY, 19 April 2012GavelNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal de CalatorieDocumento9 pagineJurnal de Calatoriemihaelaaleahim00Nessuna valutazione finora

- Language Analysis and Anticipated ProblemsDocumento3 pagineLanguage Analysis and Anticipated Problemscol89Nessuna valutazione finora

- Guia de Inglés de RepasoDocumento18 pagineGuia de Inglés de RepasoJudith MataNessuna valutazione finora

- How To EQ GuitarDocumento5 pagineHow To EQ GuitarbjbstoneNessuna valutazione finora

- The Dude 11-18-12Documento8 pagineThe Dude 11-18-12GumbNessuna valutazione finora

- Constructing Noun ClustersDocumento10 pagineConstructing Noun ClusterswulanNessuna valutazione finora

- Personality and Stylistic Features of The CommanderDocumento2 paginePersonality and Stylistic Features of The CommanderRyanLingardNessuna valutazione finora

- Headedness in MorphologyDocumento16 pagineHeadedness in MorphologyramlohaniNessuna valutazione finora

- F Scott Fitzgerald Crack Up PDFDocumento2 pagineF Scott Fitzgerald Crack Up PDFAshley0% (4)

- Fedchock Sheet Music Transcription PDFDocumento2 pagineFedchock Sheet Music Transcription PDFEric0% (1)

- Reconstructing MozartDocumento20 pagineReconstructing MozartPaulaRiveroNessuna valutazione finora

- LowePro ProductsDocumento76 pagineLowePro ProductsDavid MathiesonNessuna valutazione finora

- Food Service - CutleryDocumento132 pagineFood Service - CutleryThe 18th Century Material Culture Resource Center100% (8)

- Selectividad Exam BDocumento1 paginaSelectividad Exam BSonia PérezNessuna valutazione finora

- Added-Tone Sonorities in The Choral Music of Eric WhitacreDocumento177 pagineAdded-Tone Sonorities in The Choral Music of Eric WhitacreNgvinh Pie100% (1)

- Media Task 10 - Film Pitch PresentationDocumento10 pagineMedia Task 10 - Film Pitch PresentationAbby MoynaghNessuna valutazione finora

- Don Henley - End of The InnocenceDocumento1 paginaDon Henley - End of The InnocenceLisa MielkeNessuna valutazione finora

- I Heard A Fly BuzzDocumento3 pagineI Heard A Fly BuzzKinza SheikhNessuna valutazione finora

- 14 Folk Dances For PianoDocumento12 pagine14 Folk Dances For PianonikolettafrNessuna valutazione finora

- Jackie Review FinalDocumento2 pagineJackie Review FinalrajeevkandkurNessuna valutazione finora

- Blade Runner and VangelisDocumento2 pagineBlade Runner and VangelisMaxWitt0% (1)

- Et Screenplay PDFDocumento2 pagineEt Screenplay PDFTanya0% (1)

- Romance & Sex - ParaphernaliaDocumento108 pagineRomance & Sex - ParaphernaliaThe 18th Century Material Culture Resource Center100% (9)

- TRX CymbalGuide CympadDocumento8 pagineTRX CymbalGuide CympadFlakesJouNessuna valutazione finora

- UPSC Civil Service Exam (Main) English Paper II Question Paper 2012Documento8 pagineUPSC Civil Service Exam (Main) English Paper II Question Paper 2012moldandpressNessuna valutazione finora

- Clause, Phrase and Sentence: Noun Phrase (Subject) Verb PhraseDocumento6 pagineClause, Phrase and Sentence: Noun Phrase (Subject) Verb PhraseHaziyah binti RahmatNessuna valutazione finora