Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Who Discovered The Frank-Starling Mechanism

Caricato da

Djanino FernandesDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Who Discovered The Frank-Starling Mechanism

Caricato da

Djanino FernandesCopyright:

Formati disponibili

ARTICLES

NEWS IN PHYSIOLOGICAL SCIENCES

Who Discovered the Frank-Starling Mechanism?

Heinz-Gerd Zimmer

Carl-Ludwig-Institute of Physiology, University of Leipzig, D-04103 Leipzig, Germany

In 1866 at Carl Ludwigs Physiological Institute at Leipzig, Elias Cyon described the influence of diastolic filling of the isolated perfused frog heart on ejection volume. A study performed at the institute of the effect of filling pressure on contraction amplitude was published in 1869 by Joseph Coats, based on a recording made by Henry P. Bowditch.

n their 1926 publication, E. H. Starling and M. B. Visscher wrote Experiments carried out in this laboratory have shown that in an isolated heart, beating with a constant rhythm and well supplied with blood, the larger the diastolic volume of the heart (within physiological limits) the greater is the energy of its contraction. It is this property which accounts for the marvelous adaptability of the heart, completely separated from the central nervous system, to varying load.... (11)

This view was adopted by the subsequent generations of physiologists and still prevails in modern textbooks of physiology, which describe the Frank-Starling law of the heart as the principal mechanism by which the heart adapts to changing inflow of blood. When the cardiac muscle becomes stretched an extra amount, as it does when extra amounts of blood enter the heart chambers, the stretched muscle contracts with a greatly increased force, thereby automatically pumping the extra blood into the arteries. (6) In this review, I will show that neither Otto Frank nor Ernest H. Starling made the first observations on the effect of filling pressure on heart function. I will present evidence that the essential features of this mechanism were discovered at Carl Ludwigs Physiological Institute at the University of Leipzig in the course of the first experiments on the isolated perfused frog heart long before Otto Frank and Ernest H. Starling started their own work. Their work will be compared with these early findings.

The first observation and recording at Carl Ludwigs Physiological Institute

This phenomenon could only be discovered and studied on the isolated perfused heart. The first preparation was established at the institute by Elias Cyon in 1866. The aorta of the

0886-1714/02 5.00 2002 Int. Union Physiol. Sci./Am. Physiol. Soc. www.nips.org

isolated frog heart was connected to an artificial circulation. A side arm was inserted to enable pressure measurements with a manometer. It was a working heart preparation with recirculation. The primary aim was to study the effect of temperature on the frequency and contraction of the heart. It was observed that a certain degree of filling of the ventricle was necessary for the heart to produce a sufficient ejection volume (3). No records of the phenomenon were made. However, it can be assumed that the experience was passed on to the subsequent young investigators who came to Leipzig to work in what was then the newly built and most modern physiological institute. One of these was Joseph Coats from Glasgow, Scotland. To investigate the effects of the stimulation of the vagus, he did experiments in which this nerve was exposed from the spinal cord to the heart. The preparation was a closed, nonrecirculating system in which the heart pumped the serum with which it was filled into a manometer. The regular and consistent excursions of the mercury reflected the force developed by the heart (2). In control experiments, the effect of filling pressure on the amplitude of contractions was examined. The reference pressure was obtained when the heart was filled from a reservoir with serum before a clamp was closed. This line, labeled gg (Fig. 1), represented the balance between the floating rod on top of the mercury column, the mercury, and the serum. When the filling pressure was increased up to the diastolic pressure H, the amplitude of contraction was high (hI). When the filling pressure was reduced to the diastolic pressure H', the amplitude was lower (hII). With each further reduction in filling pressure, the excursions decreased in amplitude (hIII, hIV, hV). When the original filling pressure was restored, the previous amplitude of contraction (hVI) was reestablished (Fig. 1). This recording was made by Henry P. Bowditch, as acknowledged in a note in Coats paper (2). Furthermore, it was observed, but not recorded, that the excursions became smaller in amplitude when the filling pressure was excessively elevated. Bowditch (1840

1911) continued the work on another modification of the isolated frog heart and discovered the staircase (Treppe) phenomenon, the all-or-none law of the heart, and the absolute refractory period (1).

News Physiol Sci 17: 181

184, 2002; 10.1152/nips.01383.2002

181

FIGURE 1. Effect of lowering the filling pressure on diastolic pressure (H) and amplitude of contraction (h) of the isolated frog heart. Restoration of amplitude when original filling pressure was applied (from right to left) is shown. Recording made by H. P. Bowditch. Reprinted from Ref. 2.

The experiments of Otto Frank

Otto Frank (1865

1944) did most of his experiments in 1892

3 at Carl Ludwigs Physiological Institute, where the first observations had been made. He moved then from Leipzig to Munich, where he continued his studies in 1894 and published the results in 1895 (4), the same year in which Carl Ludwig (1816

1895) died. He looked at the heart from the viewpoint of skeletal muscle mechanics, substituting volume and pressure for length and tension. Using an improved frog heart preparation, he inserted several valves, stopcocks, and manometers in the perfusion line, which enabled him to measure isovolumetric and isotonic contractions. With increasing filling of the frog ventricle, diastolic pressure was elevated at each step. Also, the maximal isovolumetric pressure increased (contractions 1

6; Fig. 2, left). Beyond a certain filling pressure, it decreased (contraction 4; Fig. 2, right). Otto Frank compiled all of the data in the pressure-volume diagram that resulted in the diastolic pressure curve as well as in the curves of the isovolumetric and isotonic maxima. Subsequently, he was more concerned with methodological problems, such as the construction of manometers and the careful mathematical analysis of pressure curves recorded in the cardiovascular system (5). Carl Wiggers, who visited Otto Frank in 1911, was so impressed by his methods that he adopted and transferred them to the U.S. (12).

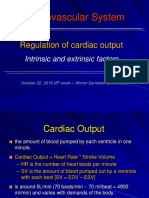

of the experimental work relating cardiac output to ventricular filling pressure. He used the dog heart-lung preparation in which peripheral resistance could be regulated independently of venous inflow. First, he determined the effect of peripheral resistance and venous pressure on cardiac output (9). As a new parameter, heart volume was measured by inserting the heart hermetically into a brass cardiometer (8). When venous inflow was increased by elevating venous pressure (bottom curve; Fig. 3, left), diastolic heart volume and stroke volume increased (upper record; Fig. 3, left). Thus the heart was able to eject the increased volume against an unchanged peripheral resistance with only a slight increase in blood pressure (middle tracing; Fig. 3, left). When peripheral resistance was elevated (increase in arterial pressure; middle tracing; Fig. 3, right), there was also an increase in diastolic volume that enabled the heart to eject a normal stroke volume (upper recording; Fig. 3, right). In both cases, diastolic fiber length was increased. In a subsequent paper, it was shown that oxygen consumption of the isolated heart is determined by its diastolic volume and therefore by the initial length of its muscular fibers (the law of the heart) (11).

Comments

The influence of diastolic filling on contraction amplitude (2) and cardiac output (3) was observed almost 30 years before Otto Frank and almost 50 years before Ernest H. Starling by young scientists working in the Carl Ludwigs Physiological Institute. Although other observations obtained there from the isolated frog heart such as the absolute refractory period and the Treppe phenomenon (1) were recognized, the

The experimental studies of Ernest Henry Starling, leading to the law of the heart

Clearly, it was Ernest H. Starling (1866

1927) who did most

FIGURE 2. Effect of increasing initial filling of the frog heart on the isometric pressure curve. The peaks of the isometric pressure curves obtained in the ventricle rose with increasing initial filling (left). Beyond a certain level of filling, the ventricular pressure peak declined (curve 4, right). Reprinted from Ref. 4. 182 News Physiol Sci Vol. 17 October 2002 www.nips.org

FIGURE 3. Changes in ventricular volume (upper recording) when the venous inflow (B, left) or the peripheral resistance was suddenly raised (C, right) in the dog heart-lung preparation. BP, arterial pressure; VP, venous pressure. Increase in ventricular volume (ml) as measured by the cardiometer is registered as a downward deflection of the upper recording (from left to right). Reprinted from Ref. 8.

effect of filling pressure on heart function was not even mentioned by the subsequent investigators. One reason may be that the young investigators of the institute had only touched on the subject in control experiments. They did not pursue the phenomenon in more detail (Table 1). Nevertheless, it was recorded (2) and described to some extent (2, 3).

Otto Frank discounted this early work as irrelevant for methodological reasons, since the modified frog heart on which Coats and Bowditch had worked was directly connected to the manometer and pumped the serum into it in a closed system (4). Obviously, he was well aware of these results (Fig. 1) (2, 3) obtained at the same institute at which he

TABLE 1. Comparison of the experimental studies describing the effect of filling of the heart on contraction and ejection Carl Ludwig Year of publication Performed at Animal used Heart preparation 1886 (3); 1869 (2) Leipzig, Germany Frog Working, recirculating (3); Closed system pumping into manometer (2) Pressure (2) Effect of temperature (3); Vagus stimulation (2) Ejection (3) and contraction amplitude dependent on filling (2) described (3); recorded (2) No Otto Frank 1895 (4); 1898 (5) Leipzig, Germany; Munich, Germany Frog Working heart dependent on preload and afterload Pressure and volume Heart as muscle and reliable pressure recording Curves of isovolumetric and isotonic maxima (5) quantified and visualized as a graph (5) No Ernest H. Starling 1914 (8, 9); 1926 (11) London, England Dog Heart-lung preparation

Parameters measured Aim of study New finding

Pressure, cardiac output, and heart volume Application to the mammalian heart Regulation of heart volume and output by preload and afterload designated the law of the heart (11) Yes

Effect Continued research focusing on the mechanism?

Numbers in parentheses are references. News Physiol Sci Vol. 17 October 2002 www.nips.org 183

did most of his experiments. When comparing Fig. 1, in which the contractions are recorded successively, with Fig. 2, left, in which the contractions are reproduced on top of each other, essentially the same phenomenon is shown. However, Otto Frank never made reference to this similarity. It seems that he was so convinced of the superiority of his improved frog heart preparation that he felt justified in disregarding the results of the earlier work. The heart-lung preparation was the basis of the experiments that led Ernest H. Starling to formulate as the law of the heart that the total energy liberated at each heartbeat is determined by the diastolic volume of the heart and therefore by the muscle fiber length at the beginning of contraction (11). However, subsequent studies showed that oxygen consumption of the heart is determined by more factors, such as heart rate, the total tension developed by the myocardium (tension-time index; Ref. 10), peak wall stress, and peak developed tension (7). From the comparison of the studies done by the group of Carl Ludwig, by Otto Frank, and by Ernest H. Starling and his associates (Table 1), it can be seen that the methodology became successively more refined so that more relevant parameters could be measured. Furthermore, the research changed from general to focused topics. The early results at Carl Ludwigs Physiological Institute were obtained while defining the control conditions in the original and in a modified isolated frog heart preparation (13). Otto Frank extended muscle physiology to the heart and subsequently became more interested in methodological problems of pressure recording. Ernest H. Starling, however, focused his research on all possible physiological aspects of the effect of diastolic fiber length on heart function, culminating in the formulation of the law of the heart (11). However, the original contributions of Elias Cyon (3), Joseph Coats (2), and Henry P. Bowditch (2) while they were working at the Leipzig Physiological Institute

should also be recognized and acknowledged to put the scientific and historical record straight.

References

1. Bowditch HP. ber die Eigenthmlichkeiten der Reizbarkeit, welche die Muskelfasern des Herzens zeigen. Berichte ber die Verhandlungen der Kniglich Schsischen Gesellschaft zu Leipzig. Mathematisch-Physische Classe 23: 652

689, 1871. 2. Coats J. Wie ndern sich durch die Erregung des n. vagus die Arbeit und die innern Reize des Herzens? Berichte ber die Verhandlungen der Kniglich Schsischen Gesellschaft zu Leipzig. Mathematisch-Physische Classe 21: 360

391, 1869. 3. Cyon E. ber den Einfluss der Temperaturnderungen auf Zahl, Dauer und Strke der Herzschlge. Berichte ber die Verhandlungen der Kniglich Schsischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Leipzig. Mathematisch-Physische Classe 18: 256

306, 1866. 4. Frank O. Zur Dynamik des Herzmuskels. Z Biol 32: 370

437, 1895. 5. Frank O. Die Grundform des arteriellen Pulses. Erste Abhandlung. Mathematische Analyse. Z Biol 37: 483

526, 1898. 6. Guyton AC. Textbook of medical physiology. London: W. B. Saunders, 1986, p. 158. 7. McDonald RH, Taylor RR, and Cingolani HE. Measurement of myocardial developed tension and its relation to oxygen consumption. Am J Physiol 211: 667

673, 1966. 8. Patterson SW, Piper H, and Starling EH. The regulation of the heart beat. J Physiol 48: 465

513, 1914. 9. Patterson SW and Starling EH. On the mechanical factors which determine the output of the ventricles. J Physiol 48: 357

379, 1914. 10. Sarnoff SJ, Braunwald E, Welch GH, Case RB, Stainsby WN, and Macruz R. Hemodynamic determinants of oxygen consumption of the heart with special reference to the tension-time index. Am J Physiol 192: 148

156, 1958. 11. Starling EH and Visscher MB. The regulation of the energy output of the heart. J Physiol 62: 243

261, 1926. 12. Wiggers CJ. The Pressure Pulses in the Cardiovascular System. London: Longmans, Green and Company, 1928. 13. Zimmer HG. Modifications of the isolated frog heart preparation in Carl Ludwigs Leipzig Physiological Institute: relevance for cardiovascular research. Can J Cardiol 16: 61

69, 2000.

184

News Physiol Sci Vol. 17 October 2002 www.nips.org

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Central Venous Pressure: Its Clinical Use and Role in Cardiovascular DynamicsDa EverandCentral Venous Pressure: Its Clinical Use and Role in Cardiovascular DynamicsNessuna valutazione finora

- Smith 1958Documento5 pagineSmith 1958AmoNessuna valutazione finora

- Frank-Starling LawDocumento5 pagineFrank-Starling LawNTA UGC-NETNessuna valutazione finora

- The Heart Is Not A PumpDocumento13 pagineThe Heart Is Not A PumpIorgos TetradisNessuna valutazione finora

- Teorias de La ContraccionDocumento24 pagineTeorias de La ContraccionCarlos Navarro alonsoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Vibrations of the HeartDocumento4 pagineThe Vibrations of the HeartEros ThanatosNessuna valutazione finora

- Otto Loewi's Discovery of Acetylcholine as the First Chemical TransmitterDocumento2 pagineOtto Loewi's Discovery of Acetylcholine as the First Chemical TransmitterDaniel RoaNessuna valutazione finora

- Skandinavisches Archiv F R Physiologie - January 1936 - Beecher - The Effect of Walking On The Venous Pressure at TheDocumento9 pagineSkandinavisches Archiv F R Physiologie - January 1936 - Beecher - The Effect of Walking On The Venous Pressure at TheIman JabilinNessuna valutazione finora

- Frank-Starling LawDocumento6 pagineFrank-Starling LawGauri RastogiNessuna valutazione finora

- Timeline Cardiac Surgery - enDocumento10 pagineTimeline Cardiac Surgery - enMaría Félix Ovalle de NavarroNessuna valutazione finora

- Noninvasive Bloodpressure PDFDocumento5 pagineNoninvasive Bloodpressure PDFduppal35Nessuna valutazione finora

- Writing the Pulse: The Origins and Career of the Sphygmograph and Its American MastersDa EverandWriting the Pulse: The Origins and Career of the Sphygmograph and Its American MastersValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Blood Pressure Measurement and HypertensionDocumento1 paginaBlood Pressure Measurement and HypertensionastamanNessuna valutazione finora

- Paediatric Cardiology ImagesDocumento65 paginePaediatric Cardiology ImagesEmy JacobNessuna valutazione finora

- The Birth of Cardiology: The Golden Decade: Braunwald's CornerDocumento2 pagineThe Birth of Cardiology: The Golden Decade: Braunwald's CornerBhageerath AttheNessuna valutazione finora

- Changes in Arterial Pressure During Mechanical Ventilation: Review ArticlesDocumento10 pagineChanges in Arterial Pressure During Mechanical Ventilation: Review ArticlessalemraghuNessuna valutazione finora

- Historia de La MH Ii2007Documento20 pagineHistoria de La MH Ii2007Carolina CortezNessuna valutazione finora

- Arterial Waveform Analysis For The AnesthesiologistDocumento11 pagineArterial Waveform Analysis For The AnesthesiologistNaser ElsuhbiNessuna valutazione finora

- Pulmonary and Systemic: THE Circulations in Congenital Heart DiseaseDocumento25 paginePulmonary and Systemic: THE Circulations in Congenital Heart DiseaseKylie GumapeNessuna valutazione finora

- Right Arterial Pressure Determinant or Result of Change in Venous Return Chest 2005Documento4 pagineRight Arterial Pressure Determinant or Result of Change in Venous Return Chest 2005Erwin RachmadNessuna valutazione finora

- Acidity Theory of AtherosclerosisDocumento46 pagineAcidity Theory of Atherosclerosissecretary6609Nessuna valutazione finora

- Regulation of the heart beatDocumento49 pagineRegulation of the heart beatCrazy BryNessuna valutazione finora

- Sarnoff StarlingDocumento9 pagineSarnoff StarlingFilippo NovelliNessuna valutazione finora

- HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT IN CARDIOLOGYDocumento3 pagineHISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT IN CARDIOLOGYneha_minnie100% (4)

- Venous pressure measurement zero level choicesDocumento10 pagineVenous pressure measurement zero level choicessondergaardNessuna valutazione finora

- Measuring Blood Pressure AccuratelyDocumento3 pagineMeasuring Blood Pressure AccuratelyAriaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardiovascular Physiology LabDocumento13 pagineCardiovascular Physiology LabMuhammadYogaWardhanaNessuna valutazione finora

- jphysiol02608-0001Documento25 paginejphysiol02608-0001Sonia PujalsNessuna valutazione finora

- 2017 Labkomp - Auskultation-Bloodpressure - Niklas IvarssonDocumento19 pagine2017 Labkomp - Auskultation-Bloodpressure - Niklas IvarssonJohn Paolo JosonNessuna valutazione finora

- AC Sup Article 14 RenalDocumento12 pagineAC Sup Article 14 RenalYuchungLeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Icu BookDocumento1.054 pagineIcu BookqsychoNessuna valutazione finora

- High Blood Pressure: Its Variations and ControlDa EverandHigh Blood Pressure: Its Variations and ControlNessuna valutazione finora

- Diastolic Dysfunction in Heart Failure Review LEEERRRDocumento18 pagineDiastolic Dysfunction in Heart Failure Review LEEERRRchris chavezNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardiology's 10 Greatest Discoveries of The 20th CenturyDocumento15 pagineCardiology's 10 Greatest Discoveries of The 20th Centurysalam08Nessuna valutazione finora

- The History of SpirometryDocumento16 pagineThe History of SpirometryRodrigo PivaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ed July 10, 1989 : Revised October 12, 198% Accepted Division of Cardiology, Elaware Street SoutheastDocumento8 pagineEd July 10, 1989 : Revised October 12, 198% Accepted Division of Cardiology, Elaware Street Southeastครูเก่งกาจ พงษ์มิตรNessuna valutazione finora

- CW Issue 22 Art2Documento5 pagineCW Issue 22 Art2Artem 521Nessuna valutazione finora

- The 12-Lead Electrocardiogram for Nurses and Allied ProfessionalsDa EverandThe 12-Lead Electrocardiogram for Nurses and Allied ProfessionalsNessuna valutazione finora

- Measure Blood Flow Velocity in Major VeinsDocumento11 pagineMeasure Blood Flow Velocity in Major VeinsNguyen Huynh SonNessuna valutazione finora

- LO Dan WO Cardio Week 5Documento60 pagineLO Dan WO Cardio Week 5Alan Dwi SetiawanNessuna valutazione finora

- BSci 1 Lab Exercise CardioVascularDocumento7 pagineBSci 1 Lab Exercise CardioVascularKearra PatacNessuna valutazione finora

- Physiology Practical 2: Toad HeartDocumento10 paginePhysiology Practical 2: Toad HeartAdams OdanjiNessuna valutazione finora

- Principles of Blood Pressure Measurement - Current Techniques, Office Vs Ambulatory Blood Pressure MeasurementDocumento12 paginePrinciples of Blood Pressure Measurement - Current Techniques, Office Vs Ambulatory Blood Pressure MeasurementindahNessuna valutazione finora

- Reports: Clinical Notes and CaseDocumento1 paginaReports: Clinical Notes and CaseJames TaylorNessuna valutazione finora

- Case 3Documento4 pagineCase 3the urvashiNessuna valutazione finora

- Oscillometric Measurement of Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressures Validated in A Physiologic Mathematical ModelDocumento22 pagineOscillometric Measurement of Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressures Validated in A Physiologic Mathematical Modelejh261Nessuna valutazione finora

- Arterial PulseDocumento2 pagineArterial PulseWwwanand111Nessuna valutazione finora

- ExcerciseexperimentDocumento3 pagineExcerciseexperimentapi-299906964Nessuna valutazione finora

- Physick to Physiology: Tales from an Oxford Life in MedicineDa EverandPhysick to Physiology: Tales from an Oxford Life in MedicineNessuna valutazione finora

- ECG & Heart Sounds: Student HandoutDocumento7 pagineECG & Heart Sounds: Student HandoutROHITNessuna valutazione finora

- Ecg Heart Sounds Laboratory HandoutDocumento7 pagineEcg Heart Sounds Laboratory HandoutShashank SahuNessuna valutazione finora

- Pulmonary Artery Catheter FindingsDocumento2 paginePulmonary Artery Catheter FindingsJakeusNessuna valutazione finora

- Jphysiol01280 0111Documento6 pagineJphysiol01280 0111stevenburrow06Nessuna valutazione finora

- Fetal Behaviour: A Neurodevelopmental ApproachDa EverandFetal Behaviour: A Neurodevelopmental ApproachNessuna valutazione finora

- Hypertension: A Comparative Review Based On Fractal Wave Theory of ContinuumDocumento8 pagineHypertension: A Comparative Review Based On Fractal Wave Theory of ContinuumAdaptive MedicineNessuna valutazione finora

- ECG & Heart Sounds LabDocumento7 pagineECG & Heart Sounds LabPatrick Joshua PascualNessuna valutazione finora

- LO's Tom W2Documento3 pagineLO's Tom W2tomvandantzigNessuna valutazione finora

- Measuring cardiac output using Fick principleDocumento1 paginaMeasuring cardiac output using Fick principledr_654737902Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cardiovascular Hemodynamics: An Introductory GuideDa EverandCardiovascular Hemodynamics: An Introductory GuideNessuna valutazione finora

- Pain, Agitation-Sedation, Delirium ProtocolDocumento4 paginePain, Agitation-Sedation, Delirium ProtocolDjanino FernandesNessuna valutazione finora

- The Origin and Conduction of The Heart BeatDocumento43 pagineThe Origin and Conduction of The Heart BeatDjanino Fernandes0% (1)

- Protecting Against Vascular Disease in BrainDocumento18 pagineProtecting Against Vascular Disease in BrainDjanino FernandesNessuna valutazione finora

- The Challenge of Translation in Social Neuroscience A Review ofDocumento22 pagineThe Challenge of Translation in Social Neuroscience A Review ofDjanino FernandesNessuna valutazione finora

- Ten Challenges For Decision NeuroscienceDocumento7 pagineTen Challenges For Decision NeuroscienceDjanino FernandesNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardiac Output 2019Documento17 pagineCardiac Output 2019crappy blue angelNessuna valutazione finora

- Congestive Heart Failure: Pediatrics 2Documento11 pagineCongestive Heart Failure: Pediatrics 2Rea Dominique CabanillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Control of Stroke VolumeDocumento2 pagineControl of Stroke VolumeNanda RahmatNessuna valutazione finora

- Vasodilator Drugs: Therapeutic Use and Rationale Therapeutic Uses of VasodilatorsDocumento6 pagineVasodilator Drugs: Therapeutic Use and Rationale Therapeutic Uses of VasodilatorsHuy NguyễnNessuna valutazione finora

- OutputDocumento12 pagineOutputzenishzalamNessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Pharmacy Answer Key-PINK PACOP PDFDocumento37 pagineClinical Pharmacy Answer Key-PINK PACOP PDFArk Olfato ParojinogNessuna valutazione finora

- Multiple Choice Questions: A. B. C. DDocumento55 pagineMultiple Choice Questions: A. B. C. DwanderagroNessuna valutazione finora

- Dilated Cardiomyopathy Notes AtfDocumento15 pagineDilated Cardiomyopathy Notes AtfSingha ChangsiriwatanaNessuna valutazione finora

- CardiacDocumento32 pagineCardiacAlli OmerNessuna valutazione finora

- All CICM Examiner ReportsDocumento432 pagineAll CICM Examiner ReportsHani MikhailNessuna valutazione finora

- Regulate Cardiac Output FactorsDocumento49 pagineRegulate Cardiac Output FactorsPeter Mukunza100% (1)

- 403 Full PDFDocumento10 pagine403 Full PDFKuroto YoshikiNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardiovascular MCQsDocumento17 pagineCardiovascular MCQsRamadan PhysiologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Elia Jennifer Perioperative Fluid Management andDocumento19 pagineElia Jennifer Perioperative Fluid Management andSiddhartha PalaciosNessuna valutazione finora

- Heart Failure - 2022Documento106 pagineHeart Failure - 2022Rana Khaled AwwadNessuna valutazione finora

- Acute Care Handbook For Physical Therapists 3rd EditionDocumento625 pagineAcute Care Handbook For Physical Therapists 3rd EditionSylvia Loong100% (2)

- Frank-Starling LawDocumento6 pagineFrank-Starling LawGauri RastogiNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts Klabu PDFDocumento257 pagineCardiovascular Physiology Concepts Klabu PDFJer100% (4)

- Physiology of The Cardiovascular System-CVSDocumento56 paginePhysiology of The Cardiovascular System-CVSAmanuel MaruNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardiovascular Physiology: Cardiac Output, Blood Flow ControlsDocumento33 pagineCardiovascular Physiology: Cardiac Output, Blood Flow ControlsLuiz Jorge MendonçaNessuna valutazione finora

- Preload and AfterloadDocumento28 paginePreload and Afterloadapi-19916399100% (1)

- Concepts of Preload and AfterloadDocumento2 pagineConcepts of Preload and AfterloadShar RiveraNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 22 - Structure and Function of The Cardiovascular and Lymphatic Systems - Nursing Test BanksDocumento36 pagineChapter 22 - Structure and Function of The Cardiovascular and Lymphatic Systems - Nursing Test BanksNeLNessuna valutazione finora

- Hemodynamic Parameters To Guide Fluid Therapy: Review Open AccessDocumento9 pagineHemodynamic Parameters To Guide Fluid Therapy: Review Open AccessClaudioValdiviaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics PDFDocumento166 paginePharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics PDFCarolina PosadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ebook Egans Fundamentals of Respiratory Care 11Th Edition Kacmarek Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocumento40 pagineEbook Egans Fundamentals of Respiratory Care 11Th Edition Kacmarek Test Bank Full Chapter PDFalexandercampbelldkcnzafgtw100% (10)

- Chapter 5 Cardiac Output and The Pressure-Volume RelationshipDocumento15 pagineChapter 5 Cardiac Output and The Pressure-Volume Relationshipaisyahasrii_Nessuna valutazione finora

- Pediatric ShockDocumento19 paginePediatric ShockdarlingcarvajalduqueNessuna valutazione finora

- Effect of Temperature On FrogDocumento2 pagineEffect of Temperature On FrogPrerna DubeyNessuna valutazione finora

- 2020 - A Physiologic Approach To Hemodynamic Monitoring and Optimizing Oxygen Delivery in Shock ResuscitationDocumento18 pagine2020 - A Physiologic Approach To Hemodynamic Monitoring and Optimizing Oxygen Delivery in Shock ResuscitationAndre OliveiraNessuna valutazione finora