Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

05 HJF Professional Autonomy

Caricato da

symphilyDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

05 HJF Professional Autonomy

Caricato da

symphilyCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Professional Autonomy: Discretion and Responsibility in K-12 Public Education

Perspectives in Practice is a series of briefing notes to promote discussion on select employment matters at issue in the K-12 public education sector. Each ends with a question to get the conversation started. Let us know what you think at contact.us@bcpsea.bc.ca.

The power or right to decide or act according to one's own judgment at work has been the subject of much discussion over the years. Traditional professions such as medicine and law uphold the autonomy of their members to make independent decisions, exercise their professional judgement, and provide services largely free of external supervision. Should the same degree of professional autonomy apply to teachers? In most jurisdictions, the phrase professional autonomy rarely appears in discussions of the K12 teaching profession. The exception is BC, where it was first used by the BC Teachers Federation (BCTF) in 1984 when the union sought legislative recognition for professional autonomy. Since then, the union has expanded the scope of what is meant by professional autonomy in the K-12 public education context. While collective agreement language generally limits teachers autonomy to choosing methods of instruction and planning and presenting course materials, the union has broadened the definition to encompass the ability of members to make decisions about the work they do and to exercise their judgment and act on it.1 Professional Autonomy: Discretion and Responsibility in K-12 Public Education discusses the concept of professional autonomy as it applies to both the education and other professions. It examines how teachers professional autonomy is necessarily more limited than that of other professions given the regulated environment in which teachers work. And finally, it looks at the responsibilities inherent in any discussion of autonomy and discretion responsibilities to the profession, the employer, the public, and students.

http://bctf.ca/IssuesInEducation.aspx?id=5638.

Professional Autonomy: Freedom and Responsibility in the Workplace

Doctors, lawyers, accountants, nurses, teachers, and other professionals enjoy varying degrees of autonomy. However, all professions impose limits on the extent of this autonomy and freedom. Self-regulating professions are governed by standards and codes of conduct that bring with them the ethical obligation to place the interests of the public ahead of the professions interests. Professional autonomy is also limited by the rules of the profession and the fact that many professionals are also employees. An independent lawyer or accountant, for example, is governed by conduct requirements and standards defined by their professional regulatory body. Many lawyers, accountants, and doctors are also employees and, as such, they are subject to the same common law legislative rights and obligations as other employees. This means that while they have the autonomy to exercise their professional judgement, they must also comply with the requirements of their employer, and failure to do so can result in discipline or termination. Employers of both professionals and others alike have considerable authority to direct the workplace, including the authority to direct their employees on the manner of performing the work. The employees right to exercise judgment about how he or she performs the work may be limited by an employers directive or rule to the contrary. Nurses and teachers are examples of professionals who are also employees and who generally work within a unionized environment. These professionals are subject to the standards defined by their regulatory colleges and the employment considerations defined within their collective agreements.

Professional Autonomy in Public Education

Do teachers have professional autonomy? Of all the criteria that are said to define a profession (which generally include shared standards of practice, monopoly over service, long periods of training, etc.), a high degree of professional autonomy is the one criterion that is most at odds with the education profession. By the very nature of their position, teachers have less autonomy than other professionals. Educators work in a regulated work environment, must generally follow a prescribed centralized curriculum, and are often asked to administer specific assessments of students on behalf of their school, district, or ministry of education. As Arbitrator James Dorsey wrote in a leading arbitration decision: The highly regulated structure of public education limits the extent to which teachers can negotiate and be contractually guaranteed freedom from control and direction by their employer and others.2 The teaching profession in BC is also very different from other professions in the province. While the teaching profession like the professions of law, medicine, accounting, nursing and

2

School District No. 62 (Sooke)/BCPSEA and the Sooke Teachers Association/BCTF, Dorsey September 22, 2009, p. 40.

many more has been granted the privilege of self-regulation by statute, the complicated nature of the relationship between the BC College of Teachers and the union means that the education profession does not have the same structures and policies in place to regulate the professional autonomy of its members. This is seen most starkly in the Colleges lack of oversight of educators professional development, compared to the rigour brought to this area by other self-regulating bodies. As Dorsey wrote: Some other professions are self-regulating within a regulatory regime and maintain and reinforce their professional autonomy through an effective system of self-regulation that imposes and enforces standards, ethics, quality service, professional development and costcontainment for the public being served. Teachers do not have this.3 Public school teachers also have less professional autonomy than their counterparts in the postsecondary environment. While some writers suggest that professional autonomy for teachers is comparable to academic freedom for university professors, the very different contexts of the two educational environments mean that they are not comparable. Students in public schools are a captive audience and they may not have the choice or capacity depending on their age and maturity to deal with controversial discussions in the classroom. Further, teachers in public schools are not engaged in the research and scholarly endeavours required at the postsecondary level, and therefore cannot lay claim to the same requirements for academic freedom or professional autonomy. Teachers are also employees who generally work in a unionized setting and are therefore bound by provisions in the collective agreement. Their dual status as both professionals and employees brings with it added obligations as they perform their duties. These duties, whether statutory or implied, require teachers to provide teaching and other educational services and they limit and/or restrict a teachers ability to exercise professional autonomy. By virtue of their status as unionized employees, teachers must negotiate the scope of their right of individual professional autonomy to provide services independent of supervision within the highly structured regulatory regime in which they work.4 Ninety-five percent of teacherpublic school employer collective agreements5 contain clauses that define the limits of teachers professional autonomy. The following example is typical: While it is recognized that the Board has the responsibility to exercise instructional leadership through its Administrative Officers in order to promote effective educational practise, teachers shall, within the bounds of the prescribed and locally developed curriculum, and consistent with effective educational practice have individual professional autonomy in determining the methods of instruction, evaluation and the planning and presentation of course materials in the classes of pupils to which they are assigned.6

3 4

ibid, p. 40. Dorsey, September 22, 2009, p. 40. 5 Although there is a centralized bargaining model in BC and a form of master collective agreement, many provisions remain from the 1987-1994 local teacher unionschool board collective bargaining period. 6 From the local agreement for School District No. 38 (Richmond), accessed at: http://bctf.ca/uploadedfiles/Public/BargainingContracts/Agreements/Local/38-Richmond.pdf.

As professionals, teachers exercise their autonomy in planning, instruction and assessment as they create high quality learning environments that meet the individual needs of their diverse students. They are expected to act in a manner consistent with effective educational practice, which requires a commitment to ongoing professional development and growth. Given the context within which they work, however, there are limits on teachers professional autonomy. The Ministry of Education is ultimately responsible for setting policy, establishing the curriculum and defining educational practices. Boards of education employ teachers to implement the ministrys vision, policies and goals. Teacher autonomy is therefore limited by the ministrys authority over the curriculum, the obligations and rights of management (in particular, to evaluate and supervise teachers), and the teachers obligation to operate consistently with effective educational practice.

The BCTF View: Limits or Threats?

In a discussion of professional autonomy, the BCTF states: Professions that have professional autonomy are characterized by the ability of members to make decisions about the work they do and by a work environment that encourages such decisions. Most of the current threats to teachers professional autonomy are not direct attacks on the ability of teachers to make decisions about the work they do, but rather erosions of the work environment that effectively limit and discourage the exercise of those decisions.7 As summarized from content on the BCTF website, these threats include: 1. The School Act and Regulations, Ministry Orders and Ministry policies. Two specific examples of limits to professional autonomy include teaching the curriculum as defined by the educational program guides (Integrated Resource Packages or other curriculum guides) and assessing student performance. BCTF publications do conclude that other than these two limitations, teachers have professional autonomy about how to assess students and what instructional and assessment strategies to use. Many of the clauses in the collective agreements do not mention assessment, and references to evaluation are usually linked to specific courses. 2. Board of education decisions, policies and motions that curtail teachers professional autonomy. Examples include mandated local report cards that exceed provincial requirements, and school-wide writes using BC performance standards to collect data for the school planning council or the districts accountability contract in the absence of any provincial requirement. The BCTF suggests that board of education decisions, policies, and motions that limit professional autonomy are open to challenge. 3. Decisions by principals. Teachers are advised to seek assistance from school union representatives and local unions to determine if something is truly a requirement and by whom, or if teachers in the local have professional autonomy in the matter in question.

http://bctf.ca/IssuesInEducation.aspx?id=563

4. Colleagues decisions. Decisions by school staff or departments can threaten an individual teachers professional autonomy. The BCTF advises that professional autonomy is an individual right we have under the collective agreement and that the majority decision of colleagues does not rule on matters of individual professional autonomy. The examples cited are a school staff decision to implement Effective Behaviour Support school-wide or a departments decision to include a final examination in a course. 5. Public pressure and the lighthouse syndrome (that is, the pressure to look good or conform to educational trends) also limit a teachers professional autonomy. These limitations are described more in terms of pressure issues rather than legal requirements. The BCTF often refers to professional autonomy when it strongly disagrees with government policy. For example, in December 2008, teachers were asked to vote on the BCTF Annual General Meeting (AGM) decision that teachers exercise their professional autonomy and not prepare for, administer, or mark the provincial FSA.8 The leadership report of the 2009 BCTF AGM identified the following as one of the BCTF priorities for 2009-2010: To enhance the professional lives and ensure the professional rights of teachers by strengthening and supporting professional autonomy, professional development, and the influence of teachers on education policy and practice. This priority has led to a series of grievances and arbitrations that test the limits of current collective agreement language and attempt to broaden the interpretation of professional autonomy provisions through litigation. Issues in dispute include: objections to provincially mandated programs, such as the Foundation Skills Assessment (FSA) objections to district-mandated assessment or efforts to promote district goals in accountability contracts (including the FSA, district-wide assessments, school-based goals related to achievement contracts, control of professional development and district guidelines regarding student participation in a specific course), and objections to collegial school-based decisions to promote achievement in goals outlined in the approved school plan for student success.

Many of these issues stem from the difficulty in reconciling what it means to be a professional operating as an employee in a regulated system accountable to the public. Teachers, seeing themselves as autonomous professionals, take issue at having their authority limited by what they perceive to be a bureaucratic, regulated, accountability-driven and assessment-focused education system.

http://bctf.ca/publications/SchoolStaffAlert.aspx?id=17068&printPage=true

Arbitration Decisions on Teacher Professional Autonomy

The alleged breach of professional autonomy rights has been the subject of several grievances and is often cited as a defence for less-than-satisfactory evaluation reports. Despite the frequency of grievances, there have only been three arbitrations on the issue of professional autonomy. These arbitrations established that professional autonomy is not a defence where the evidence establishes that the misconduct alleged against the teacher offends a standard of professionalism that all teachers can be expected to know. Grievances are generally resolved at the local level or withdrawn by the union prior to or during the arbitration. In April 1999, Arbitrator Allan Hope considered whether a two-week suspension of a teacher for making inappropriate comments in the classroom was justified. The teacher challenged the suspension as an infringement on professional autonomy. Arbitrator Hope rejected the attempt to link professional autonomy to the content of discussion in the classroom. He concluded that neither professional autonomy nor freedom of expression applied to the facts of the case: teachers remain subject to express direction with respect to how they will approach the task of teaching. The authorities invite the view that there are few subjects in public education that are as politically charged as classroom content. Content is a matter of fundamental interest to parents. It is also the subject of public policy initiatives in legislatures and provincial administrations. Finally, it is a significant topic with boards of school trustees. In this environment, teachers are subject to controls with respect to what they may teach and how they may teach it.9 In September 2009, Arbitrator James Dorsey ruled on the professional autonomy grievance of grade three teacher Kathryn Sihota in School District No. 62 (Sooke). Sihota refused to administer a district-wide reading exam (the DART assessment) because she felt it was not a useful assessment tool, and she was subsequently disciplined for insubordination by the board of education for her refusal to follow the principals direction. The union argued that the employer (principal) had no authority to ask the teacher to administer the assessment and that the board of education did not have just and reasonable cause to discipline Sihota. It relied on the professional autonomy clause in the collective agreement, which provided for "individual professional autonomy" exercised "within the bounds of the prescribed curriculum and consistent with recognized effective educational practice." In his decision, Arbitrator Dorsey held that the employer had the right, through the principal, to direct the teacher to administer the DART assessment. He stated: The direction to administer a DART assessment, in the context of the statutory scheme regulating public education and the Board of Education's responsibilities and obligations under the accountability framework, is an assignment of duties the employer has the exclusive authority to make. It is not an infringement of the individual professional autonomy guaranteed in Article F3 of the collective agreement.10

Board of School Trustees of School District #5 (Southeast Kootenay) [1999] B.C.C.A.A.A. No. 193 (Hope) (QL), paragraph 136. 10 Dorsey, September 22, 2009, p. 44-45.

Arbitrator Dorsey also stated that Sihota did not have the right to refuse the lawful direction to perform an administrative task as an exercise of her individual professional autonomy. He stated: teachers do not have unfettered discretion to comply with or refuse to comply with employer policies or directions on all matters that relate to teachers' duties and responsibilities. Teachers work and are employed in a bureaucratic professional educational enterprise. The nature and extent of their contractually guaranteed right of individual professional autonomy must be interpreted in this context.11 Whether or how the teacher chooses to use the DART assessment activity and its results in discharging the teacher's responsibility is a matter within the teacher's individual professional autonomy. The teacher can choose to embrace and integrate DART assessment into the planning, instructing, assessing and evaluating cycle or can choose to simply treat it as an additional administrative and bureaucratic burden.12 The Dorsey decision is the first arbitrated grievance between a school district and the BCTF on the districts rights versus the individual teachers professional autonomy rights based on district decisions that promote the districts mandate to improve student achievement and the methods they choose to assess the effectiveness of their goals. This decision upholds the rights of a board and its administrators to determine the overarching framework of assessments, materials, and processes to be used by teachers in meeting the specified mandate. Teachers may be required to perform such duties as administering districtand school-based student assessments, including all aspects of the testing process. Such directives do not infringe on teachers individual professional autonomy as defined in the collective agreement.

Autonomy and Responsibility

Professional autonomy lies on a continuum. As Ron Sherman wrote in an article on the issue in Teacher magazine, autonomy is a matter of degree and extent, not absolutes. It is an issue of choice and control. When we discuss the concept, we invite all kinds of qualifiers; are we talking about autonomy over curriculum, pedagogy, assessment, professional development, student discipline, and classroom environment? And if we are, how much, when, and where?13 Teachers are not independent contractors or self-employed consultants. Like other professionals, they operate within an environment where they can exercise a certain amount of autonomy. And like other professionals, they are constrained by the nature of the employer employee relationship, the standards of the profession, and expectations of quality practice. Even more so than other professions, teachers professional autonomy is also limited by the nature of their work within a highly regulated and controlled work environment and in service of our societys youngest and most vulnerable members.

11 12

Ibid, p. 41. Ibid, p. 45. 13 Sherman, Ron. Name it, frame it, and claim it, Teacher, 21.6, April 2009.

For Reflection and Discussion

In practice, how far does a teachers power or right to decide or act according to one's own judgment extend? In real terms, what does this mean at work?

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- GAMTAMOKSLINIS UGDYMAS/NATURAL SCIENCE EDUCATION, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2017Documento43 pagineGAMTAMOKSLINIS UGDYMAS/NATURAL SCIENCE EDUCATION, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2017Scientia Socialis, Ltd.Nessuna valutazione finora

- EDUCATION IN THAILAND: REFORMS AND ACHIEVEMENTSDocumento37 pagineEDUCATION IN THAILAND: REFORMS AND ACHIEVEMENTSManilyn Precillas BantasanNessuna valutazione finora

- NYU Calculus I Syllabus GuideDocumento5 pagineNYU Calculus I Syllabus Guideburner algoNessuna valutazione finora

- Essential Bibliography For English Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics PDFDocumento149 pagineEssential Bibliography For English Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics PDFEdwardSealeNessuna valutazione finora

- Preschool Benjamin Hayes - Glenbrook Ece 102 - Observation Paper TemplateDocumento7 paginePreschool Benjamin Hayes - Glenbrook Ece 102 - Observation Paper Templateapi-462573020Nessuna valutazione finora

- Laura FrycekDocumento1 paginaLaura FrycekfryceklmNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 6: Solving Problems by Finding Equivalent Ratios: Student OutcomesDocumento5 pagineLesson 6: Solving Problems by Finding Equivalent Ratios: Student Outcomesdrecosh-1Nessuna valutazione finora

- DLL English 9Documento3 pagineDLL English 9Sam C. AbantoNessuna valutazione finora

- PreK Visual Perception Classifying & MoreDocumento49 paginePreK Visual Perception Classifying & MoreHirenkumar Shah95% (22)

- Resumes of ApplicantsDocumento27 pagineResumes of ApplicantsDaily FreemanNessuna valutazione finora

- Training Proposal Ces Slac Sessions.2019.2020Documento2 pagineTraining Proposal Ces Slac Sessions.2019.2020Jemima joy antonio93% (15)

- Celebrating Community Through Art: Clarkston Unites For Church MuralDocumento20 pagineCelebrating Community Through Art: Clarkston Unites For Church MuralDonna S. SeayNessuna valutazione finora

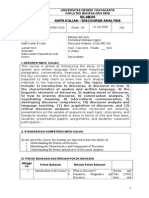

- Silabus Discourse Analysis-SdtDocumento4 pagineSilabus Discourse Analysis-SdtAnas Putra100% (1)

- Training Proposal SCHOOL INSET 2018Documento2 pagineTraining Proposal SCHOOL INSET 2018Jessete YaralNessuna valutazione finora

- Smith Resume 2023 2Documento2 pagineSmith Resume 2023 2api-511403978Nessuna valutazione finora

- Admissions DESS - Dubai English Speaking SchoolDocumento1 paginaAdmissions DESS - Dubai English Speaking SchoolbossbobNessuna valutazione finora

- Child Protection Policy Tumbao ESDocumento16 pagineChild Protection Policy Tumbao ESlloyd vincent magdaluyo50% (2)

- Find Credit Score Using Customer Bank BalancesDocumento75 pagineFind Credit Score Using Customer Bank Balancesshubham kumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Alm UndoneDocumento6 pagineAlm UndonemimayNessuna valutazione finora

- Cambridge English: Young Learners exams explainedDocumento20 pagineCambridge English: Young Learners exams explainedOscarNessuna valutazione finora

- Agenda 2021 8 17 Meeting (1039)Documento680 pagineAgenda 2021 8 17 Meeting (1039)Erika EsquivelNessuna valutazione finora

- Sat Score Reporting Code ListDocumento22 pagineSat Score Reporting Code ListenecheumiNessuna valutazione finora

- Verb To Be (Am Is Are) WorksheetDocumento2 pagineVerb To Be (Am Is Are) WorksheetClaudiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Secondary SocialisationDocumento7 pagineSecondary SocialisationKieran KennedyNessuna valutazione finora

- Flyer - F2F Feb 2019 PDFDocumento2 pagineFlyer - F2F Feb 2019 PDFBio & Chemistry LoversNessuna valutazione finora

- Physics Solved PST Papers 2069Documento13 paginePhysics Solved PST Papers 2069XPhysixZNessuna valutazione finora

- 8th Math Curriculum MapDocumento7 pagine8th Math Curriculum Mapapi-366705620100% (1)

- Admission Policy and Process - Final&approvedDocumento8 pagineAdmission Policy and Process - Final&approvedHasib Xaman KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- IrenecDocumento22 pagineIrenecapi-355789588Nessuna valutazione finora

- School of Art 2016-2017: Bulletin of Yale UniversityDocumento138 pagineSchool of Art 2016-2017: Bulletin of Yale UniversityKanyaNessuna valutazione finora