Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Sitenda Sebalu V Sam Njuba, Extension of Time To File An Appeal

Caricato da

7719901997Descrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Sitenda Sebalu V Sam Njuba, Extension of Time To File An Appeal

Caricato da

7719901997Copyright:

Formati disponibili

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF UGANDA AT MENGO CORAM: ODOKI C.J., TSEKOOKO, MULENGA, KANYEIHAMBA, AND KATUREEBE JJ.S.C.

ELECTION PETITION APPEAL NO. 26 OF 2007 BETWEEN SITENDA SEBALU::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::APPELLANT AND 1. SAM K. NJUBA 2. THE ELECTORAL COMMISSION::::::::::::::::::::RESPONDENTS [Appeal from decision of the Court of Appeal (Okello, Twinomujuni & Kitumba JJ.A) at Kampala in Election Petition Appeal No.7 of 2007 dated 1st November 2007]

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT OF THE COURT. On 7th February 2008, we allowed this appeal, set aside the trial judges order refusing extension of time and granted the appellant seven days within which to serve Notice of Presentation of Election Petition (the Notice). We reserved the reasons for our decision, which we now to give. Background The appeal arose from an Election Petition by the appellant challenging the return of the 1 st respondent as duly elected Member of Parliament for Kyadondo East Constituency, at the general Parliamentary elections held on 23rd February 2006. The petition was filed in the High Court on 18th May 2006. The appellant, as petitioner, did not serve the respondents with the Notice within seven days as required under section 62 of the Parliamentary Elections Act (PEA) and rule 6 (1) of the Parliamentary Elections (Election Petitions) Rules [PE(EP) Rules]. By 1

Notice of Motion dated 30th May 2006, filed on the same day, the appellant applied to the High Court for enlargement of time within which to serve the Notice. The application was supported by affidavit of Nsamba Abbas Matovu, affirmed on the same date. Subsequently, other affidavits and supplementary affidavits sworn/affirmed on diverse dates by Nsamba Abbas Matovu, Patrick Furah and the applicant, were filed in further support of the application. The 1 st respondent opposed the application and filed a couple of affidavits sworn by him for the purpose. After hearing the application, which included cross-examination of some deponents of affidavits as well as counsel submissions, Mwangusya J., ruled that the court had no jurisdiction to extend time fixed by statute. The learned judge added that because the 1st respondent only learnt of the petition through a newspaper advert several months after he had assumed his seat in Parliament, it would not have been in the interest of justice to grant the extension, even if the court had the jurisdiction. Accordingly he dismissed the application. On appeal to the Court of Appeal, the parties agreed on three issues for determination by that court, namely 1. whether the appellant has a right to appeal; 2. whether or not court had jurisdiction to extend time within which to serve Notice of Presentation of the Petition under s.62 of PEA; 3. if so, whether the appellant adduced special circumstances to be granted extension of time within which to serve the notice on the respondents. On the first issue the Court of Appeal held that the appellant had the right to appeal without first applying for leave because the ruling of the trial judge had conclusively determined the fate of the election petition. On the second issue the court upheld the decision of the trial judge, and added that upon failure of service of the Notice, the petition became null and void and could not be revived under rule 19 of the PE (EP) Rules. Lastly, the court held that the third issue did not arise in light of its finding on the second issue. The appellant brought this second appeal on four grounds. Counsel submissions on grounds of appeal The first three grounds, which are not drawn concisely in accordance with the Rules of this

Court, revolve around the holding that the court has no jurisdiction to extend the time fixed for serving the Notice, specifically attacking the findings that the requirement to serve the notice within 7 days is mandatory; that r.19 of PE(EP) Rules cannot apply to time fixed by statute; and that non-service of the notice rendered the petition null and void.

The fourth ground criticises the Justices of Appeal for failing to re-evaluate the evidence on special circumstances justifying the extension applied for. Counsel on both sides filed written submissions pursuant to r.94 of the Rules of the Supreme Court. In support of the appeal are joint submissions by Messrs. Bakiza & Co., Advocates and Messrs Semuyaba, Iga & Co., Advocates, while in opposition of the appeal are separate submissions by Messrs Nsibambi & Nsibambi, Advocates and the Attorney Generals Chambers, on behalf of the 1st and the 2nd respondents respectively. Counsel argue grounds 1 and 2 jointly, and the rest separately. In discussing our reasons, however, we find it more fitting to combine ground 3 with grounds 1 and 2. Counsel for the appellant contend that the provision in section 62 of PEA requiring service of the Notice to be within seven days is not mandatory but directory. They argue that the use of the word shall in a statutory provision does not necessarily make the provision mandatory, and that where the legislature intends the provision to be mandatory, it provides sanction for noncompliance with the provision. In support of that proposition, they cite the decisions in Edward Byaruhanga Katumba vs. Daniel Kiwalabye Musoke Civil Appeal No. 2/98 and David B. Kayondo vs. The Cooperative Bank Ltd. Civil Appeal No.10/91 (SC). Learned counsel also refer to guidelines for determining the intention of the legislature in the use of the word, which were approved in The Secretary of Trade and Industry vs. Langridge (1991) 3 All ER 591. Further, learned counsel contend that the Court of Appeal reliance on the case of Makula International Ltd. vs. Cardinal Nsubuga and another (1982) HCB 11 was out of context. They argue that rules 6 (1) and 19 of the PE (EP) Rules, which were made under the 1996 statute and were saved by the PEA of 2005 are intended to apply under the Act with equal statutory force. In other words, the rules, including rule 19, are not inconsistent with the PEA but were made under 3

its authority so that the Act should be construed as authorizing extension of time. They list a number of earlier cases in which time was extended under rule 19, including Edward Byaruhanga Katumba Case (supra), and Besweri Lubuye Kibuuka vs. Electoral Commission & another Constitutional Appeal No. 8/98 and others which we do not find helpful. They finally urge the Court to apply the norms of construction of statutes enunciated in Lall vs. Jeypee Investment Ltd. (1972) EA 512. On the 3rd ground of appeal, counsel for the appellant acknowledge that service of the notice within the prescribed time is a condition precedent to the trial of the petition but submit that omission to serve the notice within that time does not render the petition a nullity as held by the Court of Appeal. The petition becomes valid upon its being filed in time accompanied by payment of the due court fees. It could not be invalidated by a subsequent event. Instead, the omission could be rectified by extension of time by the court. The learned counsel contend that an election petition ought not to be defeated on a technicality and cite Shrewsbury Petition Young & another vs. Figgins The Law Times Reports p.499 in support of the proposition. They also cite several cases reported in the English Digest where extension was granted to serve notice. For the respondents it is contended that the provision under section 62 of the PEA that fixes time for service of the Notice of Presentation is mandatory and that the court discretion to grant extension of time under the subsidiary legislation cannot be exercised in respect of time fixed by statute. It is also contended that failure to effect service within the prescribed seven days renders the petition a nullity and of no effect as if it had never been filed. Counsel for the 1st respondent argue that the purpose for fixing the time of service of the notice is to ensure that election petitions are disposed of expeditiously. They contend that service of the notice within seven days is a condition precedent to existence of the petition and consequently, failure to comply renders the petition void. In support of that proposition, they referred to the case of Nair vs. Teik (1967) 2 All ER 34, in which the Privy Council considered provisions similar to section 62 of PEA and rule 6 (1) of the PE (EP) Rules and held that an election petition was a nullity due to failure of timely service. Counsel invite this Court to hold likewise. They

also rely on Besweri Lubuye Kibuuka vs. Electoral Commission & another (supra). Counsel for the 2nd respondent concede that the word shall may be used in mandatory as well as in directory statutory provisions. However, they maintain that ordinarily, the word is used to connote a mandatory command and that it is used in directory terms only in exceptional circumstances. They submit that the exceptional cases are where giving the provision in issue a mandatory interpretation would lead to absurdity or would make the provision inconsistent with the Constitution or the intention of the legislature or would cause a miscarriage of justice. Secondly, learned counsel point out that the PE (EP) Rules were made prior to the PEA, and were only saved by, but not made under that statute. According to counsel, it follows that when enacting section 62, the legislature, being aware of the existence of rules 6(1) and 19, deliberately fixed time limit for service of the notice instead of leaving the matter to be governed by the said rules, with the intention of putting the matter out of the courts jurisdiction and discretion. They submit that the rules were saved only to the extent that they are consistent with the statute and that in this regard rule 19 applies to those rules which dont merely echo provisions of the Act. Consideration of the provision in issue The contentious statutory provision is in Part X of the PEA which is concerned with the procedure for processing election petitions, where the declared election result of a Parliamentary constituency is disputed. In that part, the Act in sections 60 and 61 first provides for who may present a petition to the High Court, and the grounds upon which an election petition may be set aside. It then provides in section 62 Notice in writing of the presentation of petition accompanied by a copy of the petition shall, within seven days after the filing of the petition, be served by the petitioner on the respondent or respondents, as the case may be. (Emphasis is added) The provision is repeated virtually in the same wording in rule 6 (1) of the PE (EP) Rules, which reads Within seven days after filing the petition with the registrar, the petitioner or his or her advocate shall serve on each respondent notice in writing of the presentation 5

of the petition, accompanied by a copy of the petition. (Emphasis is added) Rule 19 of the same Rules provides The court may of its own motion or on application by any party to the proceedings, and upon such terms as the justice of the case may require, enlarge or abridge the time appointed by the Rules for doing any act if, in the opinion of the court, there exists such special circumstances as make it expedient to do so The Act does not provide for the consequences of failure to comply with the provision. It is for the court, therefore, to determine if the legislature intended the provision to be mandatory, in which case failure to comply with the provision would render the petition null and void; or if the provision is directory, in which case non-compliance would only be an irregularity that may be curable, for example by extension of time for special circumstances. It is common ground that although prima facie the use of the word shall in a statutory provision gives the provision a mandatory character, in some circumstances the word is used in a directory sense. The contention is on how to determine where the word has been used in either sense. Much as we agree with learned counsel for the appellant to the extent that where a statutory requirement is augmented by a sanction for non-compliance it is clearly mandatory, that cannot be the litmus test because all too often, particularly in procedural legislation, mandatory provisions are enacted without stipulation of sanctions to be applied in case of non-compliance. We also find that the proposal by counsel for the 2 nd respondent to restrict the directory interpretation of the word shall to only where it is shown that interpreting it as a mandatory command would lead to absurdity or to inconsistence with the Constitution or statute or would cause injustice, to be an unreliable formula, which is not supported by precedent or any other authority. The argument by the same counsel that because the legislature was aware of the existence of rules 6(1) and 19 when it enacted section 62, it must have intended to put the matter out of the discretion of the court, is non sequitur because the reverse argument is equally plausible. We were also not persuaded to follow the opinion in Nair vs. Teik (supra), as there are distinguishing features, the most significant of which is that in that case the Privy Council stated that one of the circumstances, which weighed heavily in favour of a mandatory construction was

that (ii) In contrast, for example, to the rules of the Supreme Court of this country [U.K], the rules vest no general power in the election judge to extend the time on the ground of irregularity. In this case the rules do vest in the election court the power to extend time. What is in issue is whether s. 62 ousts it in respect of service of the Notice. There is no rule of the thumb or a universal rule of interpretation, for determining if in a given statutory provision the word shall is used in the mandatory or directory sense. Two decisions of the Court of Appeal suffice to illustrate the difficulty involved in that determination. In Edward Byaruhanga Katumba vs. Daniel Kiwalabye Musoke (supra), (decided on 20. 11. 1998) the Court of Appeal concluded that a section in the Local Government Act which provides that the court shall proceed to hear and determine [election petition] within three months after the day on which the petition was filed, was not intended to be mandatory It was intended to be directory only to ensure expeditious hearing and determination of election petitions filed under the Act In Besweri Lubuye Kibuka vs. Electoral Commission and another Const. Petition No.8/98, the Constitutional Court considered a reference from the High Court (Ntabgoba P.J.) in Election Petition No.12/98, on whether in view of the same section of the Local Government Act, prescribing time limit for disposal of a petition, the trial judge could exercise residual or inherent power to extend the time within which to dispose of the petition. In its judgment, the Constitutional Court held Accordingly we hold that the judge had jurisdiction to enlarge the time laid down in [section 142(2)]. Indeed under the Parliamentary Election Statute the court has discretion to extend the period set for hearing of Parliamentary Election Petitions. Therefore, by so holding we make the law consistent in itself and we avoid confusion to practitioners. Consequently we hold that [section 142(2)] is not inconsistent with any provision of the Constitution. Significantly, in the course of its judgment the Constitutional Court observed that the trial judge could have invoked rule 19 of the PE(EP) Rules, (which was applicable by virtue of s.173 of Local Government Act) to extend the time, but was probably inhibited by the decision in Makula International Ltd. vs. His Eminence Emanuel Cardinal Nsubuga & another (supra) in 7

which the former Court of Appeal of Uganda held It is well established that a court has no residual or inherent jurisdiction to enlarge a period laid down by statute. The Constitutional Court deemed it necessary to consider if that holding meant that where time is fixed by statute it cannot be extended by court in exercise of power vested by Rules of court. It concluded In our view the correct ratio decidendi of Makula International Ltd. is that if there is no statutory provision or rule which gives the court discretion to extend or abridge the time set by statute or rule, then the court has no residual or inherent jurisdiction to enlarge a period of time laid down by the statute or rule. When the record was remitted to the High Court for disposal of the matter, including the application for extension of time, the High Court refused to grant extension of time and dismissed the petition, holding that counsel for the petitioner were guilty of dilatory conduct and that failure to comply with the statutory requirement to serve the petition on the 2nd respondent who had been declared elected, rendered the petition a nullity. On appeal, (in Besweri Lubuye Kibuka vs. Electoral Commission & another, Election Petition Appeal No.2/99, decided on 29. 6. 1999), the Court of Appeal upheld the trial judges decision. We understand that decision to be that the petition was rendered a nullity upon the court refusing to exercise its discretion to extend time, and not that the court had no power to extend the time, since by virtue of Article 137 (6) of the Constitution, both the trial court and the Court of Appeal were bound to dispose of the case in accordance with the decision of the Constitutional Court. In the instant case, however, the courts below appear to have construed or understood that decision differently. Both the trial court and the Court of Appeal held that the court had no power to extend time fixed by statute even though the rules conferred the power. In its judgment the Court of Appeal said We agree with the learned trial judge that a) The law applicable to the manner in which notice of presentation of an election petition on a respondent in effect is section 62 of the [PEA] and rule 6 of the [PE(EP)] Rules. b) In both laws, the requirement that notice of presentation must be done within seven days from the date of filing the petition are expressed in mandatory terms. c) Rule 19 of the [PE(EP)] Rules applies to where the time fixed is fixed by

rules made under the Act and cannot apply to time fixed by statute as in section 62 of the Act. We would also add that since notice of presentation of the petition was never given as prescribed, the petition became null and void and cannot be revived under rule 19 of the Rules even if that rule was applicable, which we have held it is not. See Besweri Lubuye Kibuka vs. Electoral Commission Election Petition App. No.2/99 where this court held that failure to serve the petition meant in effect that no action was in existence. With the greatest respect, it appears to us that in so holding, the Court of Appeal misconstrued its previous decision in Besweri Lubuye Kibukas appeal case and over-looked the decision of the Constitutional Court in the aforesaid reference. Be that as it may, the courts failure to follow the earlier precedents was not the basis of our decision to allow the appeal. The decision was rather based on our finding that on proper construction of the provision in section 62, it would not be correct to say that the legislature intended non-compliance with the provision, however slight or without blame, to render the petition a nullity. It cannot be overemphasised that while the court must rely on the language used in a statute to give it proper interpretation, the primary target and purpose is to discern the intention of the legislature in enacting the provision. The courts have overtime endeavoured, not without difficulty, to develop some guidelines for ascertaining the intention of the legislature in legislation that is drawn in imperative terms. One such endeavour, from which the courts in Uganda have often derived guidance is in the case of The Secretary of State for Trade and Industry vs. Langridge (1991) 3 All ER 591, in which the English Court of Appeal approved a set of guidelines that are discussed in Smiths Judicial Review of Administrative Action 4th Ed.1980, where at p.142 the learned author opines that the court must formulate its criteria for determining whether the procedural rules are to be regarded as mandatory or as directory notwithstanding that judges often stress the impracticability of specifying exact rules for categorizing the provisions. The learned author then states The whole scope and purpose of enactment must be considered and one must assess the importance of the provision that has been disregarded, and the relation of that provision to the general object intended to be secured by the Act. In assessing the importance of the provision, particular regard may be had to its significance as a protection of individual rights, the relative value that is normally 9

attached to the rights that may be adversely affected by the decision and the importance of the procedural requirement in the overall administrative scheme established by the statute. Although nullification is the natural and usual consequence of disobedience, breach of procedural or formal rules is likely to be treated as a mere irregularity if the departure from the terms of the Act is of a trivial nature or if no substantial prejudice has been suffered by those for whose benefit the requirements were introduced or if serious public inconvenience would be caused by holding them to be mandatory or if the court is for any reason disinclined to interfere with the act or decision that is impugned. (Emphasis is added) More recently, Lord Steyn aptly observed in Regina vs. Soneji and another [2005] UKHL 49 (HL Publications on Internet) that A recurrent theme in the drafting of statutes is that Parliament casts its commands in imperative form without expressly spelling out the consequences of failure to comply. It has been the source of a great deal of litigation. In the course of the last 130 years a distinction evolved between mandatory and directory requirements. The view was taken that where the requirement is mandatory, a failure to comply invalidates the act in question. Where it is merely directory a failure to comply does not invalidate what follows. There were refinements. For example, a distinction was made between two types of directory requirements, namely (1) requirements of a purely regulatory character where a failure to comply would never invalidate the act, and (2) requirements where a failure to comply would not invalidate an act provided that there was substantial compliance. He then proceeded to consider what he termed a new perspective discerned from decisions of the English Court of Appeal, the Privy Council, and courts in New Zealand, Australia and Canada and concluded Having reviewed the issue in some detail I am in respectful agreement with the Australian High Court that the rigid mandatory and directory distinction, and its many artificial refinements, have outlived their usefulness. Instead, as held in Attorney Generals Reference (No.3 of 1999), the emphasis ought to be on the consequences of non-compliance, and posing the question whether Parliament can be fairly taken to have intended total invalidity. (Emphasis is added) The view of the Australian High Court, with which we also agree, was expressed in Project Blue Sky Inc. vs. Australian Broadcasting Authority (1998) 194 CLR 355, where, after referring to the mandatory and directory classification of statutory provisions as outmoded, that court said a court, determining the validity of an act done in breach of a statutory provision, may easily focus on the wrong factors if it asks itself whether compliance with the provision is mandatory or directory, and if directory, whether there has been substantial compliance. A better test for determining the issue of validity is to ask whether it was a purpose of the legislation that an act done in breach of the

provision should be invalid.. In determining the question of purpose, regard must be had to the language of the relevant and the scope and object of the whole statute. (Emphasis is added) Conclusion We had no hesitation in answering in the negative, the question whether the purpose and intention of the legislature was to make an act done in breach of section 62 of the PEA invalid. In so doing, we noted the use of imperative language in the provision but also took into consideration the whole purpose of enactment of Part X of the PEA. It is evident from the provisions on limitation of time within which to file the petition, (section 60(3)), and to serve the Notice, (section 62), together with the directive to the trial and appellate courts to expeditiously dispose of the petition and appeals arising from it, giving them priority over other matters pending before the courts, (sections 63(2) and 66(2) and (4)), that the purpose and intention of the legislature, was to ensure, in the public interest, that disputes concerning election of peoples representatives are resolved without undue delay. In our view, however, that was not the only purpose and intention of the legislature. It cannot be gainsaid that the purpose and intention of the legislature in setting up an elaborate system for judicial inquiry into alleged electoral malpractices, and for setting aside election results found from such inquiry to be flawed on defined grounds, was to ensure, equally in the public interest, that such allegations are subjected to fair trial and determined on merit. In our view, the only way the two complimentary interests could be balanced, was to reserve discretion for ensuring that one purpose is not achieved at the expense or to the prejudice of the other. In the circumstances, the legislature could not have intended, as counsel for the 2 nd respondent submits, the rigid application of section 62, thereby excluding any court discretion over the provision, while in the same statute, in section 93, it mandates the Chief Justice, in consultation with the Attorney General, to make rules providing for practice and procedure in respect of the exercise of the courts jurisdiction in general, and for service of an election petition on the respondent in particular. [See section 93(2)(c)]. So far as is relevant here, the section provides 93. Rules of Court 1) The Chief Justice, in consultation with the Attorney General, may make rules 11

as to the practice and procedure to be observed in respect of any jurisdiction which under this Act is exercisable by the High Court and also in respect of any appeals from the exercise of that jurisdiction. 2) Without prejudice to subsection (1) any rules made under that subsection may make provision for a. b. the practice and procedure to be observed in the hearing and determining of election petitions; c. service of an election petition on the respondent d. priority to be given to hearing of election petitions Our conclusion is that through that provision the legislature authorised the making of rules providing for balancing the two complimentary interests. Rule 6 of the PE (EP) Rules, therefore, is neither ultra vires nor superfluous. It is in conformity with the said statutory mandate. Consequently, the discretion under rule 19 for enlarging the time appointed for service of the Notice, is applicable to rule 6. Accordingly, in respectful disagreement with the learned trial judge and Justices of Appeal, we found that the trial court had jurisdiction to hear and determine the appellants application for extension of time. The appellants complaint in ground 4, that the Court of Appeal erred in failing to re-evaluate the evidence showing special circumstances warranting extension of time, is well founded. In their judgment the learned Justices of Appeal said that in light of their finding that the trial court had no jurisdiction to extend time, the issue whether there was evidence of special circumstances for granting extension of time did not arise. They therefore did not consider, let alone re-evaluate the evidence. We should add that even the learned trial judge did not consider the evidence. After finding that he had no jurisdiction to grant the extension, he was content to hold that because it took six months for the 1st respondent to know, through an advert in the press, that his election was challenged in court, it would not be in the interest of justice to grant the application. Rather than remit the application to the trial court to consider the application on merit, which would have led to further considerable delay, we deemed it expedient and more in the interest of justice, for us to consider the evidence and dispose of the application. In summary, the affidavit evidence from the appellant and his former counsel who filed the petition and the application, is that after the petition was filed, the Notice could not be served

because, as a result of a litany of failures on the part of the court registry, originating from indecision on whether the file should be transferred from Kampala to Nakawa High Court registry, the period of seven days expired before the Notice issued from the court for service on the respondent. Although in his affidavit in reply the 1st respondent vehemently opposed the application, he did not refute the fact of the courts failure to issue the Notice in time. The seven days appear to have expired on 25th May 2006, and the appellant filed the application on 30th May 2006. Thereafter the litany of failures, including the file going missing from the registry at some stage, continued. In our view the failure of the court registry to issue the Notice in time constituted special circumstances for purposes of rule 19 warranting the grant of extension of time. It is for all the aforesaid reasons that we allowed the appeal. Before taking leave of the case we are constrained to comment on counsel for the appellants apparent disregard of the Rules of this Court in respect of compiling the record of appeal. The record of appeal in this case contains an incredible amount of unnecessary and irrelevant documents, such as Witness Summonses, Hearing Notices, Affidavits of Service and even a Production Warrant. Copies of original pleadings that were subsequently amended are included along with copies of the amended versions. Some of the relevant documents are inexplicably duplicated and some triplicated. To exacerbate the problem many are such faint copies that they are hardly legible. Rule 83 of the Rules of this Court elaborately sets out the list of what should be included in the record of appeal and the order of compiling it. It also provides in sub-rule (3) for exclusion of documents or parts of documents on the direction of a Justice of Appeal or a registrar of the Court of Appeal. The purpose of all that is to guide counsel to include in the record only material that is necessary for the proper hearing and determination of the appeal. We therefore urge advocates who practice in this Court to take heed of the said rules. DATED at Mengo this 22nd day of May 2008

13

B. J. Odoki CHIEF JUSTICE

J. N. W. Tsekooko JUSTICE OF SUPREME COURT J. N. Mulenga JUSTICE OF SUPREME COURT G. W. Kanyeihamba JUSTICE OF SUPREME COURT B. M. Katureebe JUSTICE OF SUPREME COURT.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- 2022 Ugcommc 93Documento9 pagine2022 Ugcommc 93viannyNessuna valutazione finora

- 2011 Ugsc 17 - 0Documento9 pagine2011 Ugsc 17 - 0Merice KizitoNessuna valutazione finora

- General Parts (U) LTD and Ors V NonPerforming Assets Recovery Trust (Civil Appeal No 9 of 2005) 2006 UGSC 3 (14 March 2006)Documento38 pagineGeneral Parts (U) LTD and Ors V NonPerforming Assets Recovery Trust (Civil Appeal No 9 of 2005) 2006 UGSC 3 (14 March 2006)Hillary MusiimeNessuna valutazione finora

- Ruling Community Justice & Anti Corruption V Law Council & Sebalu & Lule AdvocatesDocumento19 pagineRuling Community Justice & Anti Corruption V Law Council & Sebalu & Lule AdvocatesNamamm fnfmfdnNessuna valutazione finora

- 2022 TZHC 488Documento15 pagine2022 TZHC 488Marbaby SolisNessuna valutazione finora

- Neypes vs CA Land Dispute Appeal DeadlineDocumento71 pagineNeypes vs CA Land Dispute Appeal DeadlineNiala AlmarioNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court 2008 4Documento27 pagineSupreme Court 2008 4Peaches sparkNessuna valutazione finora

- Judgment of The Court: 18th & 21st February, 2022Documento19 pagineJudgment of The Court: 18th & 21st February, 2022levis victoriaNessuna valutazione finora

- Judgment of The Court: 01st & 10th June, 2021Documento12 pagineJudgment of The Court: 01st & 10th June, 2021davygabriNessuna valutazione finora

- Ruling Kintu Samuel Another V Registrar of Companies OthersDocumento10 pagineRuling Kintu Samuel Another V Registrar of Companies Othersbogere robertNessuna valutazione finora

- Norberto J. Quisumbing For RespondentsDocumento25 pagineNorberto J. Quisumbing For RespondentsYsabelleNessuna valutazione finora

- Sobetra (U) LTD Anor V Leads Insurance LTD (HCT00CCMA 377 of 2013) 2014 UGCommC 15 (13 February 2014)Documento6 pagineSobetra (U) LTD Anor V Leads Insurance LTD (HCT00CCMA 377 of 2013) 2014 UGCommC 15 (13 February 2014)Nyakoojo simonNessuna valutazione finora

- Dela Cruz v. MaerskDocumento6 pagineDela Cruz v. MaerskCamille DomingoNessuna valutazione finora

- Mona Sookram Girley Seow Neemi Batcher Polly KeastDocumento20 pagineMona Sookram Girley Seow Neemi Batcher Polly KeastDanellie GiddingsNessuna valutazione finora

- Pleadings-Parties Are Not Allowed To Open Fresh Litigation by Raising New Issues-Procedures To Raise New Issue or Open Fresh LitigationDocumento18 paginePleadings-Parties Are Not Allowed To Open Fresh Litigation by Raising New Issues-Procedures To Raise New Issue or Open Fresh LitigationMoulidy MarjebyNessuna valutazione finora

- Mohamed Selemani Suka Vs Zahara Selemani Suka 2 Others (Misc Land Appication 116 of 2022) 2022 TZHCLandD 480 (20 June 2022)Documento12 pagineMohamed Selemani Suka Vs Zahara Selemani Suka 2 Others (Misc Land Appication 116 of 2022) 2022 TZHCLandD 480 (20 June 2022)Isaya J ElishaNessuna valutazione finora

- Standard Chartered Bank (U) LTD V Mwesigwa (HCMA 477 of 2012) 2015 UGCommC 10 (27 January 2015)Documento39 pagineStandard Chartered Bank (U) LTD V Mwesigwa (HCMA 477 of 2012) 2015 UGCommC 10 (27 January 2015)rebecca namugambeNessuna valutazione finora

- Civil Case 3619 of 1983Documento14 pagineCivil Case 3619 of 1983Boss CKNessuna valutazione finora

- Kazuhiro Hasegawa and Nippon Engineering Consultants Co., LTD., Petitioners, vs. Minoru KITAMURA, Respondent. G.R. No. 149177 November 23, 2007Documento4 pagineKazuhiro Hasegawa and Nippon Engineering Consultants Co., LTD., Petitioners, vs. Minoru KITAMURA, Respondent. G.R. No. 149177 November 23, 2007chrisNessuna valutazione finora

- Rule 6 10 New Cases Civ ProDocumento29 pagineRule 6 10 New Cases Civ ProJeff Cacayurin TalattadNessuna valutazione finora

- Coram: Katureebe C.J., Tumwesigye Arach-Amoko Mwangusya Mwondha JJ.S.C.Documento17 pagineCoram: Katureebe C.J., Tumwesigye Arach-Amoko Mwangusya Mwondha JJ.S.C.Musiime Katumbire HillaryNessuna valutazione finora

- 2022 Ughccd 225Documento11 pagine2022 Ughccd 225abba williamsNessuna valutazione finora

- Abrenica v. Law Firm of Abrenica (G.r. No. 169420)Documento3 pagineAbrenica v. Law Firm of Abrenica (G.r. No. 169420)CHARMAINE KLAIRE ALONZONessuna valutazione finora

- Civil Revision No.2 of 2017..de Mello J. NEWDocumento4 pagineCivil Revision No.2 of 2017..de Mello J. NEWYussuph KhalfanNessuna valutazione finora

- Ottu & 109 Ors Versus Ami Tanzania Limited 2011Documento15 pagineOttu & 109 Ors Versus Ami Tanzania Limited 2011Riston Zela Jr.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Article 119 Cons PDFDocumento33 pagineArticle 119 Cons PDFAlex MashakaNessuna valutazione finora

- Judgment of The Court: (Nverere, J.)Documento13 pagineJudgment of The Court: (Nverere, J.)Fatema TahaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2020 TZHC 4523 - 1Documento7 pagine2020 TZHC 4523 - 1HASHIRU MDOTANessuna valutazione finora

- High Court Decision on Medical Negligence LawsuitDocumento8 pagineHigh Court Decision on Medical Negligence LawsuitjamzberryNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court Uganda 2018 13Documento33 pagineSupreme Court Uganda 2018 13Musiime Katumbire HillaryNessuna valutazione finora

- Miranda V Khoo Yew Boon - (1968) 1 MLJ 161Documento11 pagineMiranda V Khoo Yew Boon - (1968) 1 MLJ 161Nurazwa Abdul RashidNessuna valutazione finora

- 2019 Tzca 458Documento11 pagine2019 Tzca 458Saturine OscarNessuna valutazione finora

- EXTENSION OF TIME Adelay of even a single day must be counted for to enable the Court to exercise its descretion in the Applicant's favourDocumento8 pagineEXTENSION OF TIME Adelay of even a single day must be counted for to enable the Court to exercise its descretion in the Applicant's favourAmbakisye KipamilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Hasegawa v. KitamuraDocumento3 pagineHasegawa v. KitamuraIan Miranda Dela CruzNessuna valutazione finora

- USWA Petition Dismissed for Forum ShoppingDocumento3 pagineUSWA Petition Dismissed for Forum ShoppingDeric MacalinaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Ramvriksha Gond v. Babulal GondDocumento5 pagineRamvriksha Gond v. Babulal GondShreya SinhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Casalla - v. - People PDFDocumento5 pagineCasalla - v. - People PDFitsmestephNessuna valutazione finora

- Third DivisionDocumento25 pagineThird DivisionloloNessuna valutazione finora

- Civil Application 19 of 2010Documento4 pagineCivil Application 19 of 2010elisha sogomoNessuna valutazione finora

- G R No 164652 - Dumpit-Murillo Vs CA - LTDocumento7 pagineG R No 164652 - Dumpit-Murillo Vs CA - LTJoe RealNessuna valutazione finora

- Spouses David Bergonia and Luzviminda CASTILLO, Petitioners, vs. COURT OF APPEALS (4th DIVISION) and AMADO BRAVO, JR., RespondentsDocumento13 pagineSpouses David Bergonia and Luzviminda CASTILLO, Petitioners, vs. COURT OF APPEALS (4th DIVISION) and AMADO BRAVO, JR., RespondentsApple BottomNessuna valutazione finora

- Ruling ULS V KCCA & A.GDocumento15 pagineRuling ULS V KCCA & A.Gsamurai.stewart.hamiltonNessuna valutazione finora

- Namugenyi Anor V Nambi 4 Ors (Miscellaneous Application No 468 of 2016) 2016 UGHCLD 85 (3 November 2016)Documento5 pagineNamugenyi Anor V Nambi 4 Ors (Miscellaneous Application No 468 of 2016) 2016 UGHCLD 85 (3 November 2016)simon etyNessuna valutazione finora

- FACTS: Petitioners Filed An Action For Annulment of Judgment and Titles of Land And/ orDocumento3 pagineFACTS: Petitioners Filed An Action For Annulment of Judgment and Titles of Land And/ orJoshua John EspirituNessuna valutazione finora

- Civil Procedure B Group AssignmentDocumento14 pagineCivil Procedure B Group Assignmentipenguin26Nessuna valutazione finora

- Case Digest 3 - Legal Ethics (Fil Garcia vs. HernandezDocumento3 pagineCase Digest 3 - Legal Ethics (Fil Garcia vs. HernandezTom HerreraNessuna valutazione finora

- V. Frank) - The Trial Court Subsequently Denied Petitioners' Motion For ReconsiderationDocumento5 pagineV. Frank) - The Trial Court Subsequently Denied Petitioners' Motion For ReconsiderationSheena Jean Krystle LabaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Jerolan Trucking Vs CADocumento5 pagineJerolan Trucking Vs CAJof BotorNessuna valutazione finora

- Vidyabai - and - Ors - Vs - Padmalatha - and - Ors - 12122008 - Ss081749COM444438Documento7 pagineVidyabai - and - Ors - Vs - Padmalatha - and - Ors - 12122008 - Ss081749COM444438Vijay Kumar ChoudharyNessuna valutazione finora

- Tanzania Court Appeal Ruling on Land Case ExtensionDocumento8 pagineTanzania Court Appeal Ruling on Land Case ExtensionEldard KafulaNessuna valutazione finora

- Candari Vs DonascoDocumento3 pagineCandari Vs DonascoCarmelo Jay LatorreNessuna valutazione finora

- Administrator of a Certain Estate Dies, Another Administrator of That Estate Should Be Appointed, Review and Appeal,Documento17 pagineAdministrator of a Certain Estate Dies, Another Administrator of That Estate Should Be Appointed, Review and Appeal,Ambakisye KipamilaNessuna valutazione finora

- ST ST ND NDDocumento12 pagineST ST ND NDAndré Le RouxNessuna valutazione finora

- K.D. Sharma vs. Steel Authority of India Ltd. and Ors. (09.07.2008 - SC)Documento12 pagineK.D. Sharma vs. Steel Authority of India Ltd. and Ors. (09.07.2008 - SC)Zalak ModyNessuna valutazione finora

- Court Rules on Jurisdiction in Contract Dispute Between Japanese NationalsDocumento70 pagineCourt Rules on Jurisdiction in Contract Dispute Between Japanese NationalsOlek Dela CruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Jambila and Anor V Musilikani and Anor UNZASU SCJ No.1 of 2024Documento11 pagineJambila and Anor V Musilikani and Anor UNZASU SCJ No.1 of 2024besamalemaNessuna valutazione finora

- CAses For Week 2 - SCADocumento80 pagineCAses For Week 2 - SCAKristina AlcalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rules, Section 98 of The Civil Procedure Act and Section 33 of The Judicature Act. It Seeks ToDocumento7 pagineRules, Section 98 of The Civil Procedure Act and Section 33 of The Judicature Act. It Seeks ToKellyNessuna valutazione finora

- Gashumba v Nkudiye Ruling StayDocumento7 pagineGashumba v Nkudiye Ruling StayAshraf KiswiririNessuna valutazione finora

- About Legal Brains Trust - Official ProfileDocumento1 paginaAbout Legal Brains Trust - Official Profile7719901997Nessuna valutazione finora

- ULS Key Note Address FINALDocumento19 pagineULS Key Note Address FINAL7719901997Nessuna valutazione finora

- Doc. No. 1 - PetitionDocumento44 pagineDoc. No. 1 - Petition7719901997Nessuna valutazione finora

- Receivership Guide For CreditorsDocumento5 pagineReceivership Guide For Creditors7719901997Nessuna valutazione finora

- UK Representative Actions Suffer A SetbackDocumento4 pagineUK Representative Actions Suffer A Setback7719901997Nessuna valutazione finora

- BOU submission to Parliament on Uganda's oil sector revenue managementDocumento13 pagineBOU submission to Parliament on Uganda's oil sector revenue management7719901997Nessuna valutazione finora

- Reflection Paper On IHL Asia-Pacific Region WebinarDocumento3 pagineReflection Paper On IHL Asia-Pacific Region WebinarJul A.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Article 1: Power Struggles in BusinessDocumento2 pagineArticle 1: Power Struggles in BusinessSuraj GaikwadNessuna valutazione finora

- Moreland ReportDocumento101 pagineMoreland Reportliz_benjamin6490Nessuna valutazione finora

- 13 Things The Government Doesn't Want You To Know (RobertArthur Menard)Documento40 pagine13 Things The Government Doesn't Want You To Know (RobertArthur Menard)FaiezNessuna valutazione finora

- Republic V MunozDocumento2 pagineRepublic V MunozBarrrMaidenNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter-V The Relation Between Democracy and Nationalism in AmbedkarDocumento50 pagineChapter-V The Relation Between Democracy and Nationalism in AmbedkarSwaroop BojuguNessuna valutazione finora

- HST SummatyDocumento3 pagineHST SummatyAbu Naim BukharyNessuna valutazione finora

- Advantages and Disadvantages of CustomDocumento12 pagineAdvantages and Disadvantages of CustomDishant MittalNessuna valutazione finora

- Gov - Ph-Republic Act No 10592Documento3 pagineGov - Ph-Republic Act No 10592Frans Emily Perez Salvador100% (2)

- Documents From The US Espionage Den Vol. 13Documento83 pagineDocuments From The US Espionage Den Vol. 13Irdial-DiscsNessuna valutazione finora

- CasesDocumento539 pagineCasesSusan MalubagNessuna valutazione finora

- Section 6A of The DSPE ActDocumento3 pagineSection 6A of The DSPE ActDerrick HartNessuna valutazione finora

- Butler Judith Deshacer El Genero 2004 Ed Paidos 2006Documento23 pagineButler Judith Deshacer El Genero 2004 Ed Paidos 2006Ambaar GüellNessuna valutazione finora

- People Vs JalosjosDocumento2 paginePeople Vs JalosjosDavid ImbangNessuna valutazione finora

- Crafting Strategy For IwDocumento73 pagineCrafting Strategy For IwMechdi GhazaliNessuna valutazione finora

- Digest of Santos v. COMELEC (G.R. No. 155618)Documento2 pagineDigest of Santos v. COMELEC (G.R. No. 155618)Rafael Pangilinan50% (4)

- Aquino Vs Aure DigestDocumento1 paginaAquino Vs Aure Digestxyrakrezel100% (1)

- MLK Interview on Nonviolent ResistanceDocumento10 pagineMLK Interview on Nonviolent ResistanceFarook IbrahimNessuna valutazione finora

- PS21 - Final PaperDocumento8 paginePS21 - Final PaperAlby SabinianoNessuna valutazione finora

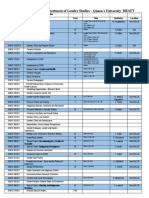

- Course Offerings With Options 2019-20 400 Level Changes JuneDocumento3 pagineCourse Offerings With Options 2019-20 400 Level Changes JuneYunuo HuangNessuna valutazione finora

- Grievance Handling - Ch4Documento13 pagineGrievance Handling - Ch4Prathamesh NawaleNessuna valutazione finora

- Bertrand Russell Speaks His MindDocumento3 pagineBertrand Russell Speaks His MindSilostNessuna valutazione finora

- Imposition of FinesDocumento13 pagineImposition of FinesAa TNessuna valutazione finora

- MarxismDocumento16 pagineMarxismKristle Jane VidadNessuna valutazione finora

- T Anjanappa and Ors Vs Somalingappa and Ors 220820S060603COM701767Documento6 pagineT Anjanappa and Ors Vs Somalingappa and Ors 220820S060603COM701767SravyaNessuna valutazione finora

- What Does American Democracy Mean To MeDocumento5 pagineWhat Does American Democracy Mean To MeCharles Garrick FlanaganNessuna valutazione finora

- John FitzgeraldDocumento1 paginaJohn FitzgeraldMartin JayNessuna valutazione finora

- Peralta Vs Municipality of Kalibo Case DigestDocumento2 paginePeralta Vs Municipality of Kalibo Case Digestjovifactor67% (3)

- The Odyssey of FYROM's Official Name (By Nicholas P. Petropoulos, Ph. D.)Documento200 pagineThe Odyssey of FYROM's Official Name (By Nicholas P. Petropoulos, Ph. D.)Macedonia - The Authentic TruthNessuna valutazione finora

- Life of QuezonDocumento12 pagineLife of QuezonMichael SomeraNessuna valutazione finora