Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Burma Seeks Legitimacy and The ASEAN Chairmanship - NEHGINPAO KIPGEN

Caricato da

Pugh Jutta0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

151 visualizzazioni6 pagineBurma Seeks Legitimacy and the ASEAN Chairmanship - Epoch Times- NEHGINPAO KIPGEN

Titolo originale

Burma Seeks Legitimacy and the ASEAN Chairmanship - NEHGINPAO KIPGEN

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoBurma Seeks Legitimacy and the ASEAN Chairmanship - Epoch Times- NEHGINPAO KIPGEN

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

151 visualizzazioni6 pagineBurma Seeks Legitimacy and The ASEAN Chairmanship - NEHGINPAO KIPGEN

Caricato da

Pugh JuttaBurma Seeks Legitimacy and the ASEAN Chairmanship - Epoch Times- NEHGINPAO KIPGEN

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 6

Burma Seeks Legitimacy and the ASEAN Chairmanship

BY NEHGINPAO KIPGEN

At the 18th summit (May7-8)

of the Association of Southeast

Asian Nations (ASEAN) in Jakarta,

Burma made a request to hold

the 2014 ASEAN chairmanship.

Observers are debating whether

Burma deserves the chairman-

ship or not. Why is it important for

the Burmese government?

The chairmanship position,

which is rotated among ASEAN

member states every year, is cur-

rently chaired by Indonesia. Cam-

bodia is set to chair in 2012, which

will be followed by Brunei in 2013.

The Burmese president Thein Sein

(former military leader and prime

minister under the State Peace

and Development Council govern-

ment) sought the support of other

ASEAN leaders.

Burma was forced to skip the

2006 chairmanship because of

pressure from within ASEAN and

from the Western democracies.

While the United States and the

European Union threatened to

boycott ASEAN meetings if Bur-

ma was to assume the role of chair,

some ASEAN members (Indonesia,

Malaysia and Singapore) feared

that it would damage the image

of ASEAN internationally.

The debate surrounding Bur-

ma’s chairmanship stems from

the question of human rights. The

idea of creating an ASEAN human

rights body was first deliberated

in 1993 by the then-foreign minis-

ters of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia,

the Philippines, Singapore, and

Thailand during the 26th ASEAN

ministerial meeting in Singapore.

However, the rights body was for-

mally established only when the

ASEAN Charter was adopted in

2007, and ratified by all members

in 2008.

Burma was given ASEAN

observer status in 1996 and full

membership in 1997. Because of

its suppression of the democracy

uprising in 1988, the detention

of Aung San Suu Kyi in 1989, and

the nullifying of the 1990 gen-

eral election result, Burma was

under heavy pressure from the

Western democracies to restore

a legitimate government or face

sanctions.

In the past few months, the

Burmese government has taken

some symbolic initiatives toward

democratic and human rights

reforms. In November 2010, the

government held a general elec-

tion and released Aung San Suu

Kyi from house arrest.

The election was, however, held

with a win-win situation for the

military-backed Union Solidar-

ity and Development Party. Suu

Kyi was released only after the

election. Subsequently, the new

government was formed in March

this year and is headed by none

other than former military gener-

als in civilian clothes.

These developments make many

to believe that Burma is moving

toward a stable democratic society,

a move welcomed by members of

ASEAN and Burma’s big trading

partners such as China and India.

The new developments have also

convinced the European Union,

in April this year, to lift travel

and financial restrictions on four

ministers, including the foreign

minister, for one year.

In spite of these symbolic devel-

opments, human rights remain a

fundamental problem. There are

still over 2,000 political prisoners

across Burma; forced labor is still

widespread; ethnic minorities still

do not find peace and security in

their own territories.

With recent developments

inside Burma, it is possible that

majority of the 10-member states,

if not by consensus, will endorse

Burma for chairmanship. This was

echoed by a joint communiqué

issued at the end of the two-day

ASEAN summit, which stated,

“We considered the proposal of

Burma that it would host the

ASEAN summits in 2014, in view

of its firm commitment to the

principles of ASEAN.”

If substantive steps are taken

to improve human rights condi-

tions, by releasing political pris-

oners unconditionally, ceasing

forced labor, arbitrary arrests, and

torture, and beginning to build

mutual trust with ethnic minori-

ties, Burma deserves its right-

ful place like any other ASEAN

member.

As ASEAN is keen on improving

ties with Western democracies,

especially with the goal of achiev-

ing a European-style community

by 2015, the voices of both the

United States and the European

Union will be a significant factor

in the final decision-making of

awarding the chairmanship to

Burma.

Awarding chairmanship can in

fact help Burma’s claim to legiti-

macy and probably boost inter-

national recognition. However,

doing so without any realistic

improvement on human rights

conditions will be tantamount to

a mockery of the ASEAN human

rights body.

It is imperative that the Bur-

mese government seeks legiti-

macy and recognition not only

from the international commu-

nity, but also from the different

ethnic groups of the country.

ASEAN has a chance to prove

that it is seriously working to

resolve human rights problems

within ASEAN institutions, as

stated in its Charter. ASEAN can

use the chairmanship position

as a leverage to improve human

rights condition inside Burma.

By chairing ASEAN, the Burmese

government hopes to gain domes-

tic and international approval.

Moreover, ASEAN chairmanship

will give Burma the opportunity

to host leaders of the Western

democracies, who otherwise will

not visit the country. It also has

the possibility of easing Western

sanctions.

Nehginpao Kipgen is a research-

er on the rise of political conflicts

in modern Burma (1947-2004)

and general secretary of the U.S.-

based Kuki International Forum

(www.kukiforum.com). Widely

published in five continents—

Asia, Africa, Australia, Europe, and

North America, Kipgen currently

pursues a Ph.D. in political science

at Northern Illinois University.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- San Luis v. San Luis (SPECPRO)Documento1 paginaSan Luis v. San Luis (SPECPRO)mileyNessuna valutazione finora

- Syllabus - Introduction To Modern Asian History - Cornell 2013Documento7 pagineSyllabus - Introduction To Modern Asian History - Cornell 2013MitchNessuna valutazione finora

- Entry of Appearance SampleDocumento2 pagineEntry of Appearance Samplefina_ong6259Nessuna valutazione finora

- Election Law ReviewerDocumento48 pagineElection Law ReviewerDarrin DelgadoNessuna valutazione finora

- ABC TriangleDocumento7 pagineABC TriangleCornelia NatasyaNessuna valutazione finora

- 05 Jurisdiction of The MTCDocumento55 pagine05 Jurisdiction of The MTCCeledonio Manubag100% (1)

- Globalization and The Asia Pacific and South AsiaDocumento14 pagineGlobalization and The Asia Pacific and South AsiaPH100% (1)

- Subject: Readings in The Philippine HistoryDocumento9 pagineSubject: Readings in The Philippine HistoryEarl averzosa100% (1)

- Republic of The Philippines vs. Court of AppealsDocumento1 paginaRepublic of The Philippines vs. Court of AppealsGlenn FortesNessuna valutazione finora

- CA Affirms RTC Ruling on Slander CaseDocumento1 paginaCA Affirms RTC Ruling on Slander CaseJordanDelaCruzNessuna valutazione finora

- HARVARD:Crackdown LETPADAUNG COPPER MINING OCT.2015Documento26 pagineHARVARD:Crackdown LETPADAUNG COPPER MINING OCT.2015Pugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- MNHRC REPORT On Letpadaungtaung IncidentDocumento11 pagineMNHRC REPORT On Letpadaungtaung IncidentPugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- #Myanmar #Nationwide #Ceasefire #Agreement #Doc #EnglishDocumento14 pagine#Myanmar #Nationwide #Ceasefire #Agreement #Doc #EnglishPugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- SOMKIAT SPEECH ENGLISH "Stop Thaksin Regime and Restart Thailand"Documento14 pagineSOMKIAT SPEECH ENGLISH "Stop Thaksin Regime and Restart Thailand"Pugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- Justice For Ko Par Gyi Aka Aung Kyaw NaingDocumento4 pagineJustice For Ko Par Gyi Aka Aung Kyaw NaingPugh Jutta100% (1)

- #NEPALQUAKE Foreigner - Nepal Police.Documento6 pagine#NEPALQUAKE Foreigner - Nepal Police.Pugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- HARVARD REPORT :myanmar Officials Implicated in War Crimes and Crimes Against HumanityDocumento84 pagineHARVARD REPORT :myanmar Officials Implicated in War Crimes and Crimes Against HumanityPugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- United Nations Office On Drugs and Crime. Opium Survey 2013Documento100 pagineUnited Nations Office On Drugs and Crime. Opium Survey 2013Pugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- UNODC Record High Methamphetamine Seizures in Southeast Asia 2013Documento162 pagineUNODC Record High Methamphetamine Seizures in Southeast Asia 2013Anonymous S7Cq7ZDgPNessuna valutazione finora

- Asia Foundation "National Public Perception Surveys of The Thai Electorate,"Documento181 pagineAsia Foundation "National Public Perception Surveys of The Thai Electorate,"Pugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- ACHC"social Responsibility" Report Upstream Ayeyawady Confluence Basin Hydropower Co., LTD.Documento60 pagineACHC"social Responsibility" Report Upstream Ayeyawady Confluence Basin Hydropower Co., LTD.Pugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rcss/ssa Statement Ethnic Armed Conference Laiza 9.nov.2013 Burmese-EnglishDocumento2 pagineRcss/ssa Statement Ethnic Armed Conference Laiza 9.nov.2013 Burmese-EnglishPugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- Modern Slavery :study of Labour Conditions in Yangon's Industrial ZonesDocumento40 pagineModern Slavery :study of Labour Conditions in Yangon's Industrial ZonesPugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

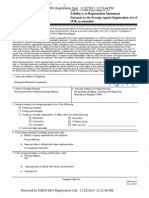

- Davenport McKesson Corporation Agreed To Provide Lobbying Services For The The Kingdom of Thailand Inside The United States CongressDocumento4 pagineDavenport McKesson Corporation Agreed To Provide Lobbying Services For The The Kingdom of Thailand Inside The United States CongressPugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- Children For HireDocumento56 pagineChildren For HirePugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- KNU and RCSS Joint Statement-October 26-English.Documento2 pagineKNU and RCSS Joint Statement-October 26-English.Pugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- BURMA Economics-of-Peace-and-Conflict-report-EnglishDocumento75 pagineBURMA Economics-of-Peace-and-Conflict-report-EnglishPugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- Myitkyina Joint Statement 2013 November 05.Documento2 pagineMyitkyina Joint Statement 2013 November 05.Pugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Dark Side of Transition Violence Against Muslims in MyanmarDocumento36 pagineThe Dark Side of Transition Violence Against Muslims in MyanmarPugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- Poverty, Displacement and Local Governance in South East Burma/Myanmar-ENGLISHDocumento44 paginePoverty, Displacement and Local Governance in South East Burma/Myanmar-ENGLISHPugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- Laiza Ethnic Armed Group Conference StatementDocumento1 paginaLaiza Ethnic Armed Group Conference StatementPugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ceasefires Sans Peace Process in Myanmar: The Shan State Army, 1989-2011Documento0 pagineCeasefires Sans Peace Process in Myanmar: The Shan State Army, 1989-2011rohingyabloggerNessuna valutazione finora

- MON HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT: DisputedTerritory - ENGL.Documento101 pagineMON HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT: DisputedTerritory - ENGL.Pugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- U Kyaw Tin UN Response by PR Myanmar Toreport of Mr. Tomas Ojea QuintanaDocumento7 pagineU Kyaw Tin UN Response by PR Myanmar Toreport of Mr. Tomas Ojea QuintanaPugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- KIO Government Agreement MyitkyinaDocumento4 pagineKIO Government Agreement MyitkyinaPugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- Brief in BumeseDocumento6 pagineBrief in BumeseKo WinNessuna valutazione finora

- Karen Refugee Committee Newsletter & Monthly Report, August 2013 (English, Karen, Burmese, Thai)Documento21 pagineKaren Refugee Committee Newsletter & Monthly Report, August 2013 (English, Karen, Burmese, Thai)Pugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- TBBC 2013-6-Mth-Rpt-Jan-JunDocumento130 pagineTBBC 2013-6-Mth-Rpt-Jan-JuntaisamyoneNessuna valutazione finora

- SHWE GAS REPORT :DrawingTheLine ENGLISHDocumento48 pagineSHWE GAS REPORT :DrawingTheLine ENGLISHPugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- Taunggyi Trust Building Conference Statement - BurmeseDocumento1 paginaTaunggyi Trust Building Conference Statement - BurmesePugh JuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- Improved Management of Alego Usonga BursariesDocumento1 paginaImproved Management of Alego Usonga BursariesTisa KenyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Firm Brochure: A Full Service Law Firm Based in Kabul, AfghanistanDocumento12 pagineFirm Brochure: A Full Service Law Firm Based in Kabul, AfghanistanAista Putra WisenewNessuna valutazione finora

- People v. Bacule G.R. No. 127568Documento1 paginaPeople v. Bacule G.R. No. 127568JP Murao IIINessuna valutazione finora

- Shubham Tripathi CV PDFDocumento3 pagineShubham Tripathi CV PDFShubham TripathiNessuna valutazione finora

- The Rise and Fall of Japanese As A Divine RaceDocumento14 pagineThe Rise and Fall of Japanese As A Divine RaceHimani RautelaNessuna valutazione finora

- Politics of Zimbabwe PDFDocumento7 paginePolitics of Zimbabwe PDFMayur PatelNessuna valutazione finora

- Forbes V Chuoco Tiaco and Crossfield, 16 Phil 534 1910 Civil ActionDocumento2 pagineForbes V Chuoco Tiaco and Crossfield, 16 Phil 534 1910 Civil ActionRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Religious Marriage in A Liberal State Gidi Sapir & Daniel StatmanDocumento26 pagineReligious Marriage in A Liberal State Gidi Sapir & Daniel StatmanR Hayim BakaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cui vs. Arellano UniversityDocumento3 pagineCui vs. Arellano UniversityDetty AbanillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Adolfo Garce - Political Knowledge RegimesDocumento30 pagineAdolfo Garce - Political Knowledge RegimesPolitics & IdeasNessuna valutazione finora

- Civic Engagement Mind Map PDFDocumento1 paginaCivic Engagement Mind Map PDFSiti RohayuNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court upholds probable cause finding vs lawyerDocumento2 pagineSupreme Court upholds probable cause finding vs lawyerKristel HipolitoNessuna valutazione finora

- Residency For Election PurposesDocumento12 pagineResidency For Election PurposesJordan GreenNessuna valutazione finora

- Senate Hearing 1954-07-16.pdf - 213541 PDFDocumento47 pagineSenate Hearing 1954-07-16.pdf - 213541 PDFSarah WhitfordNessuna valutazione finora

- 2017 Judgement 20-Mar-2018Documento89 pagine2017 Judgement 20-Mar-2018vakilchoubeyNessuna valutazione finora

- A.C. No. 270Documento3 pagineA.C. No. 270Ethan ZacharyNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Employment LawDocumento4 pagineIntroduction To Employment LawMary NjihiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Position Paper HaitiDocumento5 paginePosition Paper Haititandee villaNessuna valutazione finora

- Taxation II ReviewerDocumento9 pagineTaxation II ReviewerLiezl CatorceNessuna valutazione finora

- Ramon Magsaysay: Champion of the People"The title "TITLE"Ramon Magsaysay: Champion of the People"" highlights the key person (Ramon Magsaysay) and his notable attributes ("Champion of the PeopleDocumento2 pagineRamon Magsaysay: Champion of the People"The title "TITLE"Ramon Magsaysay: Champion of the People"" highlights the key person (Ramon Magsaysay) and his notable attributes ("Champion of the PeopleAlexander DimaliposNessuna valutazione finora