Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Hdr04 Chapter 3

Caricato da

Lim ChintakDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Hdr04 Chapter 3

Caricato da

Lim ChintakCopyright:

Formati disponibili

CHAPTER 3

Building multicultural democracies

Chapter 2 chronicles the widespread suppres- cultural identity, the dominant political project of How can states be more

sion of cultural liberty and the discrimination the 20th century. Most states influenced by this

inclusive? Democracy,

based on cultural identity—ethnic, religious thinking were deeply committed to fostering a sin-

and linguistic. How can states be more inclusive? gle, homogeneous national identity with a shared equitable development

Democracy, equitable development and state co- sense of history, values and beliefs. Recognition

and state cohesion are

hesion are essential. But also needed are multi- of ethno-cultural diversity, especially of orga-

cultural policies that explicitly recognize cultural nized, politically active and culturally differenti- essential. But also needed

differences. But such policies are resisted be- ated groups and minorities, was viewed as a

are multicultural policies

cause ruling elites want to keep their power, and serious threat to state unity, destabilizing to the

so they play on the flawed assumptions of the political and social unity achieved after historic that explicitly recognize

“myths” detailed in chapter 2. And these poli- struggles3 (feature 3.1). Other critics, often clas-

cultural differences

cies are challenged for being undemocratic and sical liberals, argue that group distinctions—such

inequitable. This chapter argues that multicul- as reserved seats in parliaments for ethnic groups,

tural policies are not only desirable but also special advantages in access to jobs, or the wear-

feasible and necessary. That individuals can ing of religious symbols—contradict principles of

have multiple and complementary identities. individual equality.

That cultures, far from fixed, are constantly The issues at stake are further complicated

evolving. And that equitable outcomes can be by demands for cultural recognition by groups

achieved by recognizing cultural differences. that are not internally democratic or represen-

This chapter also argues that states can for- tative of all their members, or by demands that

mulate policies of cultural recognition in ways that restrict rather than expand freedoms. Demands

do not contradict other goals and strategies of to continue traditional practices—such as the

human development, such as consolidating hierarchies of caste in Hindu society—may re-

democracy, building a capable state and foster- flect the interests of the dominant group in

ing more equal socio-economic opportunities. To communities intent on preserving traditional

do this, states need to recognize cultural differ- sources of power and authority, rather than the

ences in their constitutions, their laws and their interests of all members of the group.4 Legit-

institutions.1 They also need to formulate poli- imizing such claims could risk solidifying un-

cies to ensure that the interests of particular democratic practices in the name of “tradition”

groups—whether minorities or historically mar- and “authenticity”.5 It is an ongoing challenge

ginalized majorities—are not ignored or overri- to respond to these kinds of political claims.

den by the majority or by other dominant groups.2 Everywhere around the world these de-

mands for cultural recognition and the critical

RESOLVING STATE DILEMMAS IN responses to them also reflect historical injus-

RECOGNIZING CULTURAL DIFFERENCE tices and inequities. In much of the developing

world contemporary complications of cultural

Pursuing multicultural policies is not easy—given identity are intertwined with long histories of

the complexities and controversial trade-offs— colonial rule and its societal consequences.

and opponents of such policies criticize multi- Colonial views of cultural groups as fixed cat-

cultural interventions on several grounds. Some egories, formalized through colonial policies

believe that such policies undermine the build- of divide and rule (racial and ethnic categories

ing of a cohesive nation state with a homogeneous in the Caribbean6 or religious categories in

BUILDING MULTICULTURAL DEMOCRACIES 47

Feature 3.1 State unity or ethnocultural identity? Not an inevitable choice

Historically, states have tried to establish and en- defining them as the “national” language, these strategies involved many forms of cultural

hance their political legitimacy through nation- literature and history. exclusion, as documented in chapter 2, that

building strategies. They sought to secure their • Diffusion of the dominant group’s language made it difficult for people to maintain their

territories and borders, expand the adminis- and culture through national cultural insti- ways of life, language and religion or to hand

trative reach of their institutions and acquire the tutions, including state-run media and pub- down their values to their children. People feel

loyalty and obedience of their citizens through lic museums. strongly about such matters, and so resentment

policies of assimilation or integration. Attaining • Adoption of state symbols celebrating the often festered. In today’s world of increasing

these objectives was not easy, especially in a dominant group’s history, heroes and culture, democratization and global networks policies

context of cultural diversity where citizens, in reflected in such things as the choice of na- that deny cultural freedoms are less and less

addition to their identification with their coun- tional holidays or the naming of streets, build- acceptable. People are increasingly assertive

try, might also feel a strong sense of identity with ings and geographic characteristics. about protesting assimilation without choice.

their community—ethnic, religious, linguistic • Seizure of lands, forests and fisheries from mi- Assimilation policies were easier to pursue

and so on. nority groups and indigenous people and with illiterate peasant populations, as with

Most states feared that the recognition of declaring them “national” resources. Turkey’s language reform in 1928 propagating

such difference would lead to social fragmenta- • Adoption of settlement policies encouraging a single language and script. But with the rapid

tion and prevent the creation of a harmonious members of the dominant national group to spread of a culture of universal human rights

society. In short, such identity politics was con- settle in areas where minority groups histor- these conditions are fast disappearing. Efforts to

sidered a threat to state unity. In addition, ac- ically resided. impose such a strategy would be greatly chal-

commodating these differences is politically • Adoption of immigration policies that give lenged today. In any case the historical evidence

challenging, so many states have resorted to ei- preference to immigrants who share the same suggests that there need be no contradiction be-

ther suppressing these diverse identities or ig- language, religion or ethnicity as the domi- tween a commitment to one national identity

noring them in the political domain. nant group. and recognition of diverse ethnic, religious and

Policies of assimilation—often involving These strategies of assimilation and inte- linguistic identities.3

outright suppression of the identities of ethnic, gration sometimes worked to ensure political

religious or linguistic groups—try to erode the stability, but at risk of terrific human cost and Bolstering multiple and complementary

cultural differences between groups. Policies of denial of human choice. At worst, coercive as- identities

integration seek to assert a single national iden- similation involved genocidal assaults and ex- If a country’s constitution insists on the notion

tity by attempting to eliminate ethno-national and plusions of some groups. In less extreme cases of a single people, as in Israel and Slovakia, it

cultural differences from the public and politi-

cal arena, while allowing them in the private do-

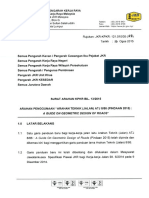

main.1 Both sets of policies assume a singular Figure Multiple and complementary national identities

national identity. 1

Spain Multiple and complementary identities

Nation building strategies privileging

singular identities

Percent 0 20 40 60 80 100

Assimilationist and integrationist strategies try to

Spain

establish singular national identities through

various interventions:2

Catalonia

• Centralization of political power, eliminat-

ing forms of local sovereignty or autonomy Basque Country

historically enjoyed by minority groups, so

that all important decisions are made in fo- Galicia

rums where the dominant group constitutes

a majority. Only Cat/ More Cat/Basque/ As Spanish as More Spanish than Only

Basque/Gal Galthan Spanish Cat/Basque/Gal Cat/Basque/Gal Spanish

• Construction of a unified legal and judicial

system, operating in the dominant group’s

language and using its legal traditions, and Belgium Multiple and complementary identities

the abolition of any pre-existing legal systems

used by minority groups. Percent 0 20 40 60 80 100

• Adoption of official-language laws, which de- Belgium

fine the dominant group’s language as the

only official national language to be used in Wallonia

the bureaucracy, courts, public services, the

Flanders

army, higher education and other official

institutions. Brussels

• Construction of a nationalized system of

compulsory education promoting standard- Only Flemish/ More Flemish/ As Belgian as Only

More Belgian than

ized curricula and teaching the dominant Walloon Walloon than Belgian Flemish/Walloon Flemish/Walloon Belgian

group’s language, literature and history and

48 HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2004

becomes difficult to find the political space to Countries such as Iceland, the Republic of Korea a “we” feeling. Citizens can find the institutional

articulate the demands of other ethnic, religious and Portugal are close to the ideal of a culturally and political space to identify with both their

or linguistic minorities and indigenous people. homogeneous nation-state. But over time even country and their other cultural identities, to

Constitutions that recognize multiple and com- states known for their homogeneity can be chal- build their trust in common institutions and to

plementary identities, as in South Africa,4 enable lenged by waves of immigration, as has happened participate in and support democratic politics. All

political, cultural and socio-economic recogni- in the Netherlands and Sweden. of these are key factors in consolidating and

tion of distinct groups. deepening democracies and building enduring

A cursory look around the globe shows that Fostering trust, support and identification “state-nations”.

national identity need not imply a single among all groups to build a democratic India’s constitution incorporates this no-

homogeneous cultural identity. Efforts to impose “state nation’’ tion. Although India is culturally diverse, com-

one can lead to social tensions and conflicts. A The solution could be to create institutions and parative surveys of long-standing democracies

state can be multi-ethnic, multilingual and multi- polices that allow for both self-rule that creates including India show that it has been very co-

religious.5 It can be explicitly binational (Bel- a sense of belonging and a pride in one’s ethnic hesive, despite its diversity. But modern India is

gium) or multi-ethnic (India). Citizens can have group and for shared rule that creates attachment facing a grave challenge to its constitutional

a solid commitment both to their state identity to a set of common institutions and symbols. An commitment to multiple and complementary

and to their own cultural (or distinct national) alternative to the nation state, then, is the “state identities with the rise of groups that seek to im-

identity.6 nation”, where various “nations”—be they eth- pose a singular Hindu identity on the country.

Belgium and Spain show how appropriate nic, religious, linguistic or indigenous identities— These threats undermine the sense of inclusion

policies can foster multiple and complementary can coexist peacefully and cooperatively in a and violate the rights of minorities in India

identities (figure 1). Appropriate policies— single state polity.7 today.8 Recent communal violence raises serious

undertaken by Belgium since the 1830s and in Case studies and analyses demonstrate that concerns for the prospects for social harmony and

Spain since its 1978 Constitution—can diminish enduring democracies can be established in poli- threatens to undermine the country’s earlier

polarization between groups within society, with ties that are multicultural. Explicit efforts are re- achievements.

the majority of citizens now asserting multiple quired to end the cultural exclusion of diverse And these achievements have been con-

and complementary identities. groups (as highlighted in the Spanish and Belgian siderable. Historically, India’s constitutional

Obviously, if people felt loyalty and affection cases) and to build multiple and complementary design recognized and responded to distinct

only for their own group, the larger state could identities. Such responsive policies provide in- group claims and enabled the polity to hold to-

fall apart—consider the former Yugoslavia. centives to build a feeling of unity in diversity— gether despite enormous regional, linguistic and

cultural diversity.9 As evident from India’s per-

formance on indicators of identification, trust

Figure Trust, support and identification: poor and diverse countries can do and support (figure 2), its citizens are deeply

2 well with multicultural policies committed to the country and to democracy, de-

Support for democracy Trust in institutions spite the country’s diverse and highly stratified

National identification

society. This performance is particularly im-

Democracy is preferable to any other Great deal, quite (%) How proud are you to be a national of…

form of government (%) 1996–98a 1995–97a Great deal, quite (%) 1995–97a pressive when compared with that of other

100

long-standing—and wealthier—democracies.

Percent

United

States Austria The challenge is in reinvigorating India’s com-

Canadac mitment to practices of pluralism, institutional

Australia India

Spain accommodation and conflict resolution through

Uruguay Argentina

Spain

Belgium

democratic means.

80 India Brazil

Critical for building a multicultural democ-

Switzerland racy is a recognition of the shortcomings of his-

torical nation-building exercises and of the

benefits of multiple and complementary identi-

60 India ties. Also important are efforts to build the

Canadac Germany loyalties of all groups in society through identi-

Chile

Austriab Switzerland fication, trust and support.

Brazil Korea,

Rep. of Brazil National cohesion does not require the

Belgiumb

40

imposition of a single identity and the denun-

Germany United

States ciation of diversity. Successful strategies to

Spain

Australia build ”state-nations” can and do accommo-

30

date diversity constructively by crafting re-

20 sponsive policies of cultural recognition. They

Argentina are effective solutions for ensuring the longer

terms objectives of political stability and social

harmony.

0

Note: Percentages exclude ‘don’t know/no answer’ replies. a. The most recent year available during the period specified. b. Data refer to

1992. c. The most recent year during the period 1990–93.

Source: Bhargava 2004; Kymlicka 2004; Stepan, Linz and Yadav

2004.

BUILDING MULTICULTURAL DEMOCRACIES 49

South Asia, for example), continue to have pro- explores how states are integrating cultural

found consequences.7 Contemporary states thus recognition into their human development strate-

cannot hope to address these problems without gies in five areas:

some appreciation of the historical legacies of • Policies for ensuring the political partici-

racism, slavery and colonial conquest. pation of diverse cultural groups.

But while multicultural policies thus must • Policies on religion and religious practice

confront complexity and challenges in balanc- • Policies on customary law and legal pluralism.

ing cultural recognition and state unity, suc- • Policies on the use of multiple languages.

cessful resolution is possible (see feature 3.1). • Policies for redressing socio-economic

Many states have accommodated diverse groups exclusion.

and extended their cultural freedoms without

Redressing the cultural compromising their unity or territorial integrity. POLICIES FOR ENSURING THE POLITICAL

Policy interventions to minimize exclusive and PARTICIPATION OF DIVERSE CULTURAL GROUPS

exclusion of minorities

conflictual political identities have often pre-

and other marginalized vented or helped to end violent conflict. Poli- Many minorities and other historically margin-

cies of multicultural accommodation have also alized groups are excluded from real political

groups requires explicit

enhanced state capacity and promoted social har- power and so feel alienated from the state (chap-

multicultural policies to mony by bolstering multiple and complemen- ter 2). In some cases the exclusion is due to a

tary identities. lack of democracy or a denial of political rights.

ensure cultural

Redressing the cultural exclusion of mi- If so, moving to democracy will help. But some-

recognition norities and other marginalized groups requires thing more is required, because even when

more than providing for their civil and political members of such groups have equal political

freedoms through instruments of majoritarian rights in a democracy, they may be consistently

democracy and equitable socio-economic poli- underrepresented or outvoted, and so view the

cies.8 It requires explicit multicultural policies central government as alien and oppressive.

to ensure cultural recognition.9 This chapter Not surprisingly, many minorities resist alien or

oppressive rule and seek more political power.

BOX 3.1 That is why a multicultural conception of

A rough guide to federalism democracy is often required. Several models of

Federalism is a system of political organiza- One identity or many. “Mono-national”

multicultural democracies have developed in re-

tion based on a constitutionally guaranteed or “national” federations assert a single national cent years that provide effective mechanisms of

balance between shared rule and self-rule. It identity, as in Australia, Austria and Germany. power sharing between culturally diverse

involves at least two levels of government— “Multi-national” federations, such as Malaysia groups. Such arrangements are crucial for se-

a central authority and its constituent re- and Switzerland, constitutionally recognize

curing the rights of diverse cultural groups and

gional units. The constituent units enjoy multiple identities. Other states combine the

autonomy and power over constitutionally two. India and Spain assert a single national for preventing violations of these rights by ma-

defined subjects—they can also play a role identity but recognize plural aspects of their joritarian imposition or by the political domi-

in shaping the policies of the central gov- heterogeneous polity—say, by accommodat- nance of the ruling elite.

ernment. The degree and scope of autonomy ing diverse linguistic groups. Considered here are two broad categories of

varies widely. Some countries, such as Brazil, Symmetric or asymmetric. In sym-

grant considerable powers to their regions. metric federalism the constituent units have

democratic arrangements in which culturally

Others, such as Argentina, retain overriding identical—that is symmetric—powers, re- diverse groups and minorities can share power

control at the centre. lations and obligations relative to the cen- within political processes and state institutions.

Some other important distinctions: tral authority and each other, as in The first involves sharing power territorially

Coming together or holding together. Australia. In asymmetric federalism some

through federalism and its various forms. Fed-

In “coming together” federal arrangements, provinces enjoy different powers. In

as in Australia or Switzerland, the regions Canada, for example, asymmetric federal eral arrangements involve establishing territor-

chose to form a single federal polity. In powers provided a way of reconciling Que- ial subunits within a state for minorities to

“holding together” arrangements, such as in bec to the federal system by awarding it spe- exercise considerable autonomy (box 3.1). This

Belgium, Canada and Spain, the central gov- cific powers connected to the protection form of power-sharing arrangement is relevant

ernment devolved political authority to the and promotion of French-Canadian lan-

regions to maintain a single unified state. guage and culture. where minorities are territorially concentrated

Source: Stepan 2001.

and where they have a tradition of self-govern-

ment that they are unwilling to surrender.

50 HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2004

The second category of arrangements in- authority, thereby reducing violent clashes and

volves power sharing through consociations, demands for secession.

using a series of instruments to ensure the par- There are several flourishing examples of

ticipation of culturally diverse groups dispersed such entities. Almost every peaceful, long-

throughout the country. These arrangements standing democracy that is ethnically diverse is

address claims made by groups that are not ter- not only federal but asymmetrically so. For in-

ritorially concentrated or do not demand au- stance, Belgium is divided into three regions

tonomy or self-rule. Consociations are based on (the Walloon, Flemish, and Brussels-Capital re-

the principle of proportionality: the ethnic or cul- gions), two established according to linguistic cri-

tural composition of society is proportionally mir- teria (the Walloon region for French- and

rored in the institutions of the state. Achieving German-speaking people and the Flemish region

proportionality requires specific mechanisms for Dutch-speaking people). The Swiss federa- Several models of

and policies. Electoral arrangements such as tion also encompasses different linguistic and

multicultural democracies

proportional representation can better reflect cultural identities.

group composition, as can the use of reserved In Spain the status of “comunidades autóno- provide effective

seats and quotas in the executive and legislature. mas” has been accorded to the Basque country,

mechanisms of power

Both federal and consociational types of Catalonia, Galicia and 14 other entities. These

power-sharing arrangements are common around communities have been granted a broad, and sharing between

the world. Neither is a panacea, but there are widely varying, range of autonomous powers in

culturally diverse groups

many successful examples of both. This chapter such areas as culture, education, language and

looks at a particular kind of federal arrangement economy. The three historic regions were given

and some specific mechanisms of consociation distinct areas of autonomy and self-rule. The

that are particularly suited to enabling the political Basque communities and Navarra have been

participation of diverse cultural groups. granted explicit tax and expenditure powers be-

yond those of other autonomous communities.

POWER SHARING THROUGH FEDERAL Spain’s willingness to accommodate the distinct

ARRANGEMENTS : ASYMMETRIC FEDERALISM demands of its regions has helped to mitigate con-

flicts and separatist movements. Such proactive

Federalism provides practical ways of managing interventions have helped to foster acceptance of

conflict in multicultural societies10 through de- multiple identities and to marginalize the exclu-

mocratic and representative institutions—and of sive ones—identities solely as Basque, Galician,

enabling people to live together even as they Catalan or Spanish (see feature 3.1).

maintain their diversity.11 Sometimes the polit- Many federations have failed, however.12

ical demands of culturally diverse groups can be Federal arrangements that attempted to create

accommodated by explicitly recognizing group ethnically “pure” mono-national subterritories

diversity and treating particular regions differ- have broken down in many parts of the world.

ently from others on specific issues. In such Yugoslavia is a prominent example. The federal

“asymmetric” federal systems the powers arrangements were not democratic. The units

granted to subunits are not identical. Some re- in the federation had been “put together” and

gions have different areas of autonomy from were ruled with highly unequal shares of politi-

others. Federal states can thus accommodate cal and economic power among the key groups,

some subunits by recognizing specific distinc- an arrangement that fostered ethnic conflict that

tions in their political, administrative and eco- eventually became territorial conflict, and the

nomic structures, as Malaysia did when the federation fell apart. This collapse is sometimes

Borneo states of Sabah and Sarawak joined the attributed to a flawed federal design that failed

federation in 1963. This allows greater flexibil- to establish free and democratic processes and

ity to respond to distinct demands and to ac- institutions through which ethnic groups could

commodate diversity. These special measures articulate multiple identities and build comple-

enable territorially concentrated group distinc- mentarity. Instead it reinforced demands for

tions to politically coexist with the central separation, thus ending in political disintegration.

BUILDING MULTICULTURAL DEMOCRACIES 51

The success of federal arrangements de- is often worth much more than the administra-

pends on careful design and the political will to tive costs that such arrangements incur.13

enhance the system’s democratic functioning. Many states fear that self-rule or “home rule”

What matters is whether the arrangements ac- could undermine their unity and integrity. Yet

commodate important differences, yet buttress many states have granted territorial autonomy

national loyalties. For example, federal structures without negative consequences. These efforts to

that merely respond to demands for the desig- enhance group representation and participation

nation of “exclusive” or “mono-national” home- have sometimes staved off political violence and

republics for ethnic groups may go against the secessionist movements. For example, after

idea of multiple and complementary identities. decades-long struggle, the First Nations people

Such political deals, and communal concessions of northern Canada negotiated a political agree-

The success of federal that do not foster loyalty to common institutions, ment14 with the federal government to create

can introduce divisive tendencies in the polity, the self-governing territory of Nunavut in 1999.15

arrangements depends on

which present ongoing challenges, as in the case In Panama several indigenous people—the Bri

careful design and the of Nigeria (box 3.2). Bri, Bugle, Embera, Kuna, Naso, Ngobe and

In addition, history shows that asymmetric Wounaan—have constituted semiautonomous re-

political will to enhance

federalism, introduced early enough, can help re- gions governed by local councils.

the system’s democratic duce the likelihood of violent secessionist move- Article 1 of the International Covenant on

ments. The avoidance of violent conflict through Civil and Political Rights expresses the world’s

functioning

various federal arrangements introduced in the agreement that “All peoples have the right of

early stages of emerging secessionist movements self-determination. By virtue of that right they

BOX 3.2

The challenge of federalism: Nigeria’s troubled political trajectory and prospects

Nigeria is home to more than 350 ethnic groups, 1976, 21 in 1987, 30 in 1991 and 36 in 1999. • Instituting affirmative action policies in ed-

but more than half the country’s 121 million The hope was that this would encourage more ucation and the civil service. This has come

people belong to three main groups: the Hausa- flexible ethnic loyalties and alliances. More im- to include rotation of the presidency among

Fulani, Muslims in the north; the Yoruba, fol- mediately, this expanding federal structure has six geopolitical zones: north-west, north-

lowers of both Christian and Islamic faiths, in the helped contain local ethnic disputes, diffus- east, north-central, south-west, south-east

South-West; and the Igbo, most of whom are ing the power of the three major ethnic groups and south-central and appointment of at

Christians, in the South-East. Smaller groups and preventing the absolute domination of the least one federal minister from each of the

have tended to cluster around these three groups, more than 350 smaller minority groups. 36 states according to the zoning principle.

creating unstable and ethnically divisive politics. • Devising electoral rules to produce govern- These measures provide a functional frame-

Africa’s largest country has had a troubled ments that would enjoy broadly national work for economic distribution that tries to

political history marked by military coups and and majority support. In the elections for the avoid unitary and centralizing excesses and

failed civilian governments. The country has Second Republic of 1979–83, a presiden- domination by the centre.

had military governments for 28 of its 44 years tial candidate with a plurality of the votes The return of democracy has reanimated re-

of independence. Nigeria is attempting to ensure could be declared winner only after obtain- gional, ethnic, religious and local identities and

that its return to civilian rule after 16 years of dic- ing at least 25% of the votes in two-thirds of intensified communal mobilization. This has

tatorship under the Abacha regime will be a the states. The 1999 Constitution updated led to the social violence that has engulfed the

genuine process of democratic consolidation. the threshold rule: to compete for the elec- country since the return to civilian rule, whereas

The 1999 Constitution addresses the two tions a party must secure at least 5% of the previously such conflicts were coercively sup-

concerns of an excessively powerful centre and votes cast in at least 25 of the 36 states in local pressed by the military regimes. Political stability

parochial concerns at the state levels, as well as government elections. While the threshold in Nigeria is still threatened by massive struc-

the unhealthy dynamic of patronage, rent-seeking rule relating to party formation was rescinded tural socio-economic inequalities between the

and competition between these levels. It has in- in 2003, the threshold rule for declaring a North and South, the high level of state de-

stituted several reforms, including: party the winner, and thus for forming a pendence on federally collected oil revenues

• Gradually dissolving the three federal regimes government, still holds, encouraging the for- and the intense competition and corruption of

inherited from the colonial era and replacing mation of multi-ethnic parties. Many other public life linked to its distribution—and the

them with a decentralized system of 36 states issues of federal relations introduced by the unresolved question of rotating the presidency

and 775 local governments. The three re- 1999 Constitution continue to be hotly con- between the six ethno-political zones, which

gions were transformed into four in 1963. tested, including those on revenues, property has incited violence and ethnic cleavages. The

The 4 regions became 12 states in 1967, 19 in rights, legal codes and states’ prerogatives. challenges are tremendous—and ongoing.

Source: Bangura 2004; Lewis 2003; Rotimi 2001.

52 HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2004

freely determine their political status and freely power sharing, proportional representation in

pursue their economic, social and cultural de- electoral systems, provisions for cultural au-

velopment”. The application of this principle to tonomy, and safeguards in the form of mutual

people within independent states and to in- vetoes. These instruments can help to prevent

digenous people remains controversial. The one segment of society from imposing its views

constitutions of such countries as Mexico and on another. In their most effective form they can

the Philippines have taken some steps to rec- help to reflect the diverse cultural composition

ognize the rights of indigenous people to self- of a society in its state institutions. Consociation

determination, but others avoid it. arrangements are sometimes criticized as un-

One of the legal instruments indigenous democratic because they are seen as an instru-

people have used to mobilize around these issues ment of elite dominance, through the co-option

is the International Labour Organization’s of opposition or vulnerable groups.18 But they Another sign that these

Convention (169) Concerning Indigeonous and need not involve a “grand coalition” of parties:

struggles for cultural

Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries, passed they require only cross-community representa-

in 1989 and open for ratification since 1990.16 tion in the executive and legislature. The chal- recognition have entered

As of 2003 it had only 17 signatories—Argentina, lenge is to ensure that neither self-rule (for

the global debate is the

Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Denmark, minorities) nor shared rule (of the state as a

Dominica, Ecuador, Fiji, Guatemala, Honduras, whole) outweighs the other. These arrange- recent meetings of the

Mexico, the Netherlands, Norway, Paraguay, ments also have to be addressed through pru-

Permanent Forum on

Peru and Venezuela.17 Chile’s Congress has dent and responsible politics.

voted against several initiatives in this direction. This section focuses on two mechanisms of Indigenous Issues at the

The Organization of Africa Unity approved the consociations—executive power sharing and

United Nations

African Charter on Human and People’s Rights, proportional representation—that prevent the

but nowhere is the term “people” defined. dominance of a majority community.19 From a

Another sign that these struggles for cultural constitutional point of view measures that priv-

recognition have entered the global debate is the ilege minorities in election procedures raise

recent meetings of the Permanent Forum on In- questions of equal treatment. But small and

digenous Issues at the United Nations. Political scattered minorities do not stand a chance of

developments seem to be concentrated in regions being represented in majoritarian democracies

of the world that have explicitly recognized without assistance. Executive power sharing

claims of indigenous people, who have mobilized can protect their interests. Proportionality in

to contest their exclusion. Some see such mo- such political and executive arrangements mir-

bilizations as politically disruptive—as their vi- rors the diverse composition of society in its

olent and reactionary versions can be—but these state institutions.

movements also reflect greater awareness of Belize, Guyana, Suriname, and Trinidad

cultural liberty. States can no longer afford to and Tobago have long used power-sharing

ignore or suppress these claims. mechanisms to address racial and ethnic divi-

There have been some imaginative initiatives sions, with varying success.20 The mechanisms

to grant autonomy and self-rule, especially when involve elements of autonomy (self-government

groups extend across national boundaries. An for each community) and integration (joint gov-

example is the Council for Cooperation on Sami ernment of all the communities). Political power

issues set up jointly by Finland, Norway and is shared in executives, in legislatures and (in

Sweden. principle) in judiciaries.21

Care has to be taken to ensure that a minor-

POWER SHARING THROUGH CONSOCIATION : ity’s potential for winning the appropriate num-

PROPORTIONALITY AND REPRESENTATIVE ber of seats is not sabotaged—as in Northern

ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS Ireland. During the era of “home rule” from

1920 to 1972 constituencies were repeatedly ger-

Consociation applies the principle of propor- rymandered to the disadvantage of the Catholic

tionality in four key areas: through executive nationalist parties and others and in favour of the

BUILDING MULTICULTURAL DEMOCRACIES 53

dominant Ulster Unionist Party, which governed New Zealand (box 3.3).23 Proportional repre-

uninterrupted, often without taking the interests sentation is most effective in stable democracies

of the nationalist minority into account. This and can remedy some of the major deficiencies

eventually provoked a long-lasting reaction of of majoritarian electoral systems by strengthening

conflict and violence. The Good Friday Agree- the electoral voice of minorities. Proportional

ment of 1998 sought to avoid repeating this his- representation is not the sole solution in all cir-

tory. The agreement calls for key decisions at the cumstances. Innovations in winner-takes-all sys-

Assembly of Northern Ireland to be decided on tems can also bolster the voice of minorities,

a “cross-community basis”. This requires either though such arrangements are considerably

parallel consent of both blocs independently or more difficult to engineer.

in a weighted majority of 60% of votes, with Other approaches to ensuring representa-

Exclusion may be less 40% of voting members of each bloc.22 The idea tion of cultural minorities include reserving seats

is that no important decision can be taken with- for certain groups, as New Zealand does for the

direct and perhaps even

out some support from both sides, providing a Maoris,24 India for scheduled tribes and castes and

unintended, as when the framework for negotiation. Croatia for Hungarians, Italians, Germans and

In Belgium the Assembly and Senate are others. Reserved seats and quotas are sometimes

public calendar does not

divided into language groups—one Dutch- and criticized because they “fix” peoples’ identities and

recognize a minority’s one French-speaking group, with the German- preferences in the electoral mechanism. And

speaking group defined as a part of the French negotiating quotas and reservations can lead to

religious holidays

group. Certain key questions have to be de- conflict and grievances. In Lebanon Muslim griev-

cided by a majority in each group and by an over- ances over a quota of 6:5 seats in the parliament

all majority of two-thirds of votes. In majoritarian between Christians and Muslims, fixed on the

democracy the majority rules; in consociational basis of the 1932 census, became an important

democracies power-sharing majorities from all source of tension and led to civil war when the

groups rule. demographic weight of the two communities

Proportional representation, another in- changed.25 These approaches can be more prob-

strument of consociation, allows each significant lematic than proportional electoral systems, which

community to be represented politically in rough leave people free to choose their identifications.

accord with its share of the population, partic-

ularly when parties are ethnically based. Even POLICIES ON RELIGION AND RELIGIOUS

when they are not, proportional representation PRACTICE

provides greater incentives for political parties

to seek votes from dispersed groups who do As chapter 2 shows, many religious minorities

not form majorities in any particular geograph- around the world suffer various forms of exclu-

ical constituency—and this also boosts minor- sion. In some cases this is due to explicit

ity representation. Proportional representation discrimination against a religious minority—a

does not guarantee successful accommodation, problem particularly common in non-secular

and a winner-takes-all system can sometimes countries where the state has the task of up-

be compatible with multinational and multi- holding and promoting an established religion. But

lingual federations, as Canada and India have in other cases the exclusion may be less direct and

demonstrated. But both countries also use other perhaps even unintended, as when the public

measures to ensure political representation for calendar does not recognize a minority’s religious

various groups, and winner-takes-all systems holidays, or the dress codes in public institutions

can also lead to tyrannies of the majority. conflict with a minority’s religious dress, or state

None of the many electoral rules of pro- rules on marriage and inheritance differ from

portional representation provide perfect pro- those of a minority religion, or zoning regula-

portionality. But they can address the problem tions conflict with a minority’s burial practices.

of winner-takes-all systems and enable greater These sorts of conflicts can arise even in secular

representation of minorities and other groups, states. Given the profound importance of religion

as shown in the impact of recent reforms in to people’s identities, it is not surprising that

54 HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2004

BOX 3.3

Proportional representation or winner takes all? New Zealand makes a switch

Majoritarian democracies have a dismal record Several multicultural states rely on proportional Largely to address the underrepresentation

on political participation by minorities, under- representation systems, including Angola, Bosnia of the indigenous Maori population, New

representing them and marginalizing their elec- and Herzegovina, Guyana and Latvia. In West- Zealand in 1993 voted to undertake a major

toral voice. How can multicultural societies be ern Europe 21 of 28 countries use some form of electoral reform, from winner takes all to pro-

more inclusive and ensure adequate participation proportional representation. portional representation. Colonial legislation

of minorities and other marginalized cultural Critics of proportional representation argue dating to 1867 assigned 4 of the 99 seats in gov-

groups? One way is through proportional rep- that the incorporation of fragmented groups ernment to the Maori, far short of their 15%

resentation rather than winner-takes-all systems. could lead to unstable, inefficient governments, share in the population. Voters chose a mixed-

In winner-takes-all (also called first-past-the- with shifting coalitions; Italy is often cited. But member proportional system, a hybrid in which

post) systems, the political party with the most such problems are neither endemic nor insur- half the legislative seats come from single-seat,

votes gets a majority of the legislative seats. In mountable. Indeed, several mechanisms can pre- winner-takes-all districts and half are allocated

the United Kingdom, for example, a party can vent stalemates and deadlocks. For example, according to the percentage of votes won by

(and often does) win less than 50% of the vote instituting minimum vote requirements, as in each party.

but gets a much bigger share of seats in the Germany, or changing the number of districts New Zealand also incorporated a “dual

House of Commons. In the 2001 election the to reflect the geographic dispersion of public constituency” system in which individuals of

Labour party won 41% of the vote and walked opinion can alleviate these problems while main- Maori descent were given the option of voting

away with 61% of the seats. In the same election taining inclusive legislative systems. And stale- either for an individual from the Maori roll or

Liberal Democrats received 19.4% of the vote but mate and deadlock may be preferable to a for an individual on the general electoral roll.

only 7.5% of the seats. In proportional repre- minority imposing its will on the majority—as Maori seats are allocated based on the Maori cen-

sentation systems legislatures are elected from often happens with governments elected under sus and by the proportion of Maori individuals

multiseat districts in proportion to the number winner-takes-all systems. who choose to register on the Maori roll.

of votes received: 20% of the popular vote wins Others resist these policies on grounds that New Zealand’s first election under pro-

20% of the seats. such changes would entail tremendous upheavals portional representation (in 1996) was difficult.

Because winner-takes-all systems exclude and political instability—as feared by the polit- A majority coalition did not form for nine

those who do not support the views of the party ical elite in many Latin American countries months, and public opinion swayed back in

in power, they do not lend themselves to cul- where indigenous populations are increasingly favour of the winner-takes-all system. But the

turally inclusive environments. But in propor- demanding greater political voice and repre- 1999 and 2002 elections ran smoothly, restoring

tional representation systems parties that get a sentation. However, this argument cannot be public support for proportional representation.

significant number of votes are likely to get a used to defend policies that result in the con- Maori political representation increased from

share of power. As a rule, then, proportional rep- tinued exclusion of certain groups and sections. around 3% in 1993 to almost 16% in 2002. De-

resentation voting systems provide a more ac- Transitions to prudent politics that encourage spite problems along the way it is clear that elec-

curate reflection of public opinion and are likely greater participation and enable more effective toral transition went a long way towards

to foster the inclusion of minorities (as long as representation are possible, as the experiences improving the representation of the Maori pop-

minorities organize themselves in political form). of other democratic countries show. ulation in New Zealand.

Source: O’Leary 2004; Boothroyd 2004; Nagel 2004.

religious minorities often mobilize to contest for the state’s ability to protect individual choice

these exclusions. If not managed properly, these and religious freedoms (box 3.4).

mobilizations can become violent. So it is vital for Sometimes problems arise because of too

states to learn how to manage these claims. many formal links between regions and the state

The state is responsible for ensuring policies or too much influence by religious authorities

and mechanisms that protect individual choice. in matters of state. This can happen when, say,

This is best achieved when public institutions do a small clerical elite controls the institutions of

not discriminate between believers and non-be- the state in accord with what it considers divinely

lievers, not just among followers of different re- commissioned laws, as in Afghanistan under

ligions. Secular principles have been proven to the Taliban. These politically dominant reli-

work best towards these goals, but no one sin- gious elites are unlikely to tolerate internal dif-

gle model of secularism is demonstrably better ferences, let alone dissent, and unlikely to extend

than others in all circumstances. Various links be- freedoms even to their own members outside the

tween state and religious authorities have evolved small ruling elite, much less to members of

over time. Similarly, states that profess to be sec- other religious groups. Such states do not ac-

ular do so differently both in principle and in commodate other religious groups or dissenters

practice. And these differences have implications or treat them equally.

BUILDING MULTICULTURAL DEMOCRACIES 55

BOX 3.4

The many forms of secular and non-secular states and their effects on religious freedom

States have treated religion in different ways. Anti-religious, secular states However, it is willing to defend universal princi-

The state excludes religion from its own affairs ples of human rights and equal citizenship and is

Non-secular states without excluding itself from the affairs of reli- able to intervene in the internal affairs of reli-

A non-secular state extends official recognition gion. In such a state the right to religious free- gious groups in what can be called “principled dis-

to specific religions and can assume different dom is very limited, and often the state intervenes tance”. This engagement may take the form of

forms depending on its formal and substantive to restrict religious freedoms and practice. Com- even-handed support for religions (such as pub-

links with religious authority. munist regimes in China and former communist lic funding of religious schools or state recogni-

• A state governed by divine law—that is, a regimes in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe tion of religious personal law) or even of

theocracy, such as the Islamic Republic of are examples. intervention to monitor and reform religious prac-

Iran run by ayatollahs or Afghanistan under tices that contradict human rights (such as regu-

the Taliban. Neutral or disengaged states lating religious schools or reforming personal

• A state where one religion benefits from There are two ways of expressing this kind of neu- laws to ensure gender equality). With principled

a formal alliance with the government— trality. The state may profess a policy of “mutual distance, whether the state intervenes or refrains

that is, having an “established” religion. exclusion”, or the “strict separation of religion from interfering depends on what measures really

Examples include Islam in Bangladesh, and state”. This means that not only does the state strengthen religious liberty and equality of citi-

Libya and Malaysia; Hinduism in Nepal; prevent religious authorities from intervening in zenship. The state may not relate to every religion

Catholicism in Argentina, Bolivia and the affairs of state, but the state also avoids in- in exactly the same way or intervene to the same

Costa Rica; and Buddhism in Bhutan, terfering in the internal affairs of religious groups. degree or in the same manner. But it ensures that

Burma and Thailand. One consequence of this mutual exclusion is the relations between religious and political in-

• A state that has an established church or that the state may be unable or unwilling to in- stitutions are guided by consistent, non-sectarian

religion, but that nonetheless respects terfere in practices designated as “religious” even principles of liberty and human rights.

more than one religion, that recognizes when they threaten individual rights and demo- An example is the secular design in the In-

and perhaps attempts to nurture all reli- cratic values. Or the state may have a policy of dian Constitution. While the growth of com-

gions without any preference of one over neutrality towards all religions. The clearest ex- munal violence makes observers skeptical of the

the other. Such states may levy a religious amples are the state of Virginia (after the dises- secular credentials of Indian politicians these

tax on all citizens and yet grant them the tablishment of the Anglican Church in 1786), the days, the Constitution established India as a sec-

freedom to remit the tax money to religious United States (particularly after the First Amend- ular state. It was this policy of secularism with

organizations of their choice. They may fi- ment to its Constitution in 1791) and France, es- principled distance that enabled the Indian state

nancially assist schools run by religious pecially after the Separation Law of 1905. in the early years after independence to recog-

institutions but in a non-discriminatory nize the customary laws, codes and practices of

way. Examples of such states include Swe- Secular states asserting equal respect and minority religious communities and enable their

den and the United Kingdom. Both are vir- principled distance cultural integration. It enabled positive inter-

tually secular and have established religions The state is secular, in the sense that it does not ventions upholding principles of equality and lib-

only in name. Other examples of this pat- have an established church and does not promote erty by reforming a range of customary practices,

tern of non-secular states are Denmark, one religion over others, but rather accords equal such as prohibiting erstwhile “untouchables”

Iceland and Norway. respect to all religions (and to non-believers). from entering temples.

Source: Bhargava 2004.

In other instances the state may profess neu- states should protect three dimensions of reli-

trality and purportedly exclude itself from mat- gious freedom and individual choice:

ters of religion and exclude religion from matters • Every individual or sect within a religious

of state—a policy of “mutual exclusion”. But in group should have the right to criticize, re-

reality this stance may become distorted through vise or challenge the dominance of a par-

policies that are blind to actual violations of re- ticular interpretation of core beliefs. All

ligious freedoms or through ad hoc interventions religions have numerous interpretations and

motivated by political expedience. practices—they are multivocal—and no sin-

Whatever the historical links with religion, gle interpretation should be sponsored by the

states have a responsibility to protect rights and state. Clergy or other religious hierarchies

secure freedoms for all their members and not should have the same status as other citizens

discriminate (for or against) on grounds of and should not claim greater political or

religion. It is difficult to propose an optimal societal privilege.

design for the relations between state institutions • States must give space to all religions for in-

and religious authority. But non-discriminatory terfaith discussion and, within limits, for

56 HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2004

critiques. People of one religion must be al- Sometimes this historical baggage appears

lowed to be responsibly critical of the prac- in contemporary dilemmas—of whether to rec-

tices and beliefs of other religions. ognize different religious laws in a democratic

• Individuals must be free not only to criticize environment where all citizens have equality

the religion into which they are born, but to before the law. As the ongoing discussions on

reject it for another or to remain without one. the uniform civil code in India demonstrates, the

Some challenges to secularism arise from a arguments for women’s rights and principles of

country’s historical links with religion or from equality get entangled with concerns for mi-

the legacy of colonialism. The British divide- nority rights and cultural recognition (box 3.5).

and-rule policies in South Asia, which at- Building consensus on these issues to advance

tempted to categorize religious and cultural universal principles of human rights, gender

identities, fixing their relative positions in the equality and human development has to be the The arguments for

polity and in society, have been a source of guiding principle for resolving them.27

women’s rights and

continuing political conflict even after the ter-

ritorial partitions in the region.26 These his- POLICIES ON CUSTOMARY LAW AND LEGAL principles of equality get

torically entrenched divisions remain as serious PLURALISM

entangled with concerns

barriers to secular policies in a region that has

witnessed so much communal trauma. The Certain religious and ethnic minorities and in- for minority rights and

Spanish colonial rulers, with their historical digenous groups feel alienated from the larger

cultural recognition

links with the Catholic Church, left a legacy of legal system, for a number of reasons. In some

similar links between state and church in their countries judges and other court officials have

former colonies, especially in Latin America, historically been prejudiced against them, or

with implications for concerns of gender equal- ignorant of their conditions, resulting in the

ity, among others. unfair and biased application of the law. In

BOX 3.5

Hindu and Muslim personal law: the ongoing debate over a uniform civil code

Legal pluralism and legal universalism are hotly intervene in matters of religious practice to equality before the law, but fail to appreciate the

debated in India today. Should a single legal assert liberty and equality while protecting difficult position of minorities. This is particu-

system apply to members of all communities? the right of groups to practice their religion. larly relevant in the light of growing communal

The differences highlight the apparent contra- It is important to understand the debate in tensions. The Muslim minority often views the

diction of the constitutional recognition of Hindu historical context. India’s leadership at inde- code as an underhand abrogation of their cul-

and Muslim personal laws and the parallel con- pendence was committed to a secular India, not tural freedom.

stitutional commitment to a uniform civil code. just a state for its Hindu majority. This was po- Personal laws of all communities have been

The debate is thus embedded in larger concerns litically imperative given the fears of the Muslim criticized for disadvantaging women, and there

about India as a multicultural secular state. minority immediately after the brutal partition are strong arguments for reforming almost all tra-

Personal laws, specific to different religious of the subcontinent. The Indian Constitution ditional (and usually patriarchal) laws and cus-

communities, govern marriage, divorce, guardian- recognized and accommodated its colonially in- toms in the country, bringing Hindu and Muslim

ship, adoption, inheritance and succession. They herited system of legal pluralism as its multicul- personal or customary laws in line with gender

vary widely between and even within the same tural reality. The ultimate goal of a unified civil equality and universal human rights. But im-

community. Court cases involving personal law code was included in the Constitution, and the plementing equality—an objective that is central

also raise their own more particular issues, some- Special Marriages Act of 1954 offered couples a to concerns of human development—is not the

times pitting minority religious groups’ rights non-religious alternative to personal laws. same as implementing uniformity.

against women’s rights. A brief scan of legal developments over the What is needed is internal reform of all cus-

The debate over personal laws often comes 1980s and 1990s highlights how the argument for tomary laws, upholding gender equality rather

down to the following: uniformity has overlooked concerns for than imposing identical gender-biased, preju-

• Gender equality—how patriarchal cus- equality—and how the secular agenda has been dicial laws across all communities. Crucial in

toms and laws, be they Hindu or Muslim, depicted as being antithetical to the principle of this is a genuine effort to establish consensus on

treat men and women differently in terms special recognition of the cultural rights of mi- the code. Legislation imposing uniformity will

of their legal entitlements. norities. The ongoing debate is important be- only widen the majority-minority divide—

• Cultural freedoms and minority rights— cause of the contemporary political context. detrimental both for communal harmony and for

whether the state should reserve the right to Supporters of the code assert principles of gender equality.

Source: Engineer 2003; Mody 2003; Rudolph 2001.

BUILDING MULTICULTURAL DEMOCRACIES 57

many countries indigenous people are almost en- manipulation and control. An added compli-

tirely unrepresented in the judiciary. This real- cation in separating authentic from imposed

ity of bias and exclusion is exacerbated by the practices is that colonial rule and its “civilizing

inaccessibility of the legal system to these groups mission” unilaterally claimed responsibility for

for additional reasons, including geographical introducing modern values, beliefs and institu-

distance, financial cost and language or other cul- tions to the colonies.31

tural barriers. In Africa European colonialists introduced

Plural legal systems can counter this exclu- their own metropolitan law and system of courts.

sion. But some critics argue that plural legal But they retained much customary law and

systems can legitimize traditional practices that many elements of the African judicial process

are inconsistent with expansion of freedoms. that they deemed consistent with their sense of

All legal systems must Many traditional practices reject the equality of justice and morality. Western-type courts were

women, for example, in property rights, inher- presided over by expatriate magistrates and

conform to international

itance, family law and other realms.28 But legal judges whose jurisdiction extended over all per-

standards of human pluralism does not require the wholesale adop- sons, African and non-African, in criminal and

tion of all practices claimed to be “traditional”. civil matters. Often referred to as “general

rights, including gender

The accommodation of customary law cannot courts”, they applied European law and local

equality be seen as an entitlement to maintain practices statutes based on European practices. A second

that violate human rights, no matter how “tra- group of “native-authority courts” or “African

ditional” or “authentic” they may claim to be.29 courts” or “people’s courts” comprised either

From a human development perspective all traditional chiefs or local elders. These courts

legal systems—whether unitary or plural—must had jurisdiction over only Africans and for the

conform to international standards of human most part applied the prevailing customary law.

rights, including gender equality. Other critics Throughout Malawi’s colonial history, for ex-

therefore argue that if the legal system of the ample, jurisdiction over Africans was left to the

larger society respects human rights norms, and traditional courts for cases involving customary

if indigenous people accept these norms, there law and for simple criminal cases.32

is no need to maintain legal pluralism. But even Towards the end of the colonial period, of-

where there is a consensus on human rights ficials began to integrate the dual courts system,

norms, there may still be a valuable role for with the general courts supervising the workings

legal pluralism. of the customary courts. The Anglophone

Plural legal systems exist in almost all soci- colonies retained much of the dual legal struc-

eties, evolving as local traditions were historically ture created during colonial rule while at-

accommodated along with other formal sys- tempting to reform and adapt customary law to

tems of jurisprudence.30 Customary practices, notions of English law. Francophone and Lu-

which acquired the force of law over time, co- sophone colonies tried to absorb customary law

existed alongside introduced systems of ju- into the general law. Ethiopia and Tunisia abol-

risprudence. Such legal pluralism often had ished some aspects of customary law. But in no

roots in the colonial logic of protection of mi- African country, either during or after the colo-

nority rights, which allowed certain customary nial era, has customary law been totally disre-

systems to continue while imposing the colo- garded or proscribed.

nizer’s own laws.

CUSTOMARY LAW CAN PROMOTE ACCESS TO

COLONIAL CONSTRUCTIONS , YET JUSTICE SYSTEMS

CONTEMPORARY REALITIES

Accommodating customary law can help pro-

The colonial imprint can be marked. Indeed, it tect the rights of indigenous people and en-

often is difficult to determine which legal sure a fairer application of the rule of law.

processes are genuinely traditional and which Efforts to accord public recognition to cus-

can be seen as a hybrid by-product of colonial tomary law can help create a sense of inclusion

58 HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2004

in the wider society. Often the most pragmatic a dollar for a hearing. The judges use everyday

case for customary law, especially in parts of language, and the rules of evidence allow the

failed states, is that the choice is between cus- community to interject and question testimony.

tomary law and no law. Recognizing the abil- The system has its critics—particularly

ity of indigenous people to adopt and administer women, who are barred from serving as judges

their own laws is also a repudiation of historic and are often discriminated against as litigants.

prejudice—and can be an important part of Even so, women’s groups, under the umbrella

self-government for indigenous people.33 of the Rural Women’s Movement, are on the

Countries from Australia to Canada to vanguard of efforts to recognize customary law

Guatemala to South Africa have recognized and adapt it to post-apartheid society. They are

legal pluralism. In Australia there has been a re- leading discussions about how to elevate cus-

newed focus on recognizing Aboriginal and tomary law and make it fairer to women. Accommodating

Torres Strait Islander customary law, which has Still a concern, therefore, is how customary

customary law can help

opened the way to indigenous community mech- law compromises or ensures human rights stan-

anisms of justice, aboriginal courts, greater re- dards.35 Any legal system—conventional or protect the rights of

gional autonomy and indigenous governance. In customary—is open to criticism over its formu-

indigenous people and

Canada most local criminal matters are dealt lation. A legal tradition is a set of deeply rooted,

with by the indigenous community so that the historically conditioned attitudes about the na- ensure a fairer application

accused can be judged by jurors of peers who ture of law, about the role of law in society,

of the rule of law

share cultural norms. In Guataemala the 1996 about the proper organization and operation of

peace accords acknowledged the need to rec- a legal system and about the way law should be

ognize Mayan law as an important part of gen- made, applied, studied, perfected and taught.

uine reform (box 3.6).

In post-apartheid South Africa a ground- BOX 3.6

swell of innovation is instilling new authority, re- Access to justice and cultural recognition in Guatemala

sources and dignity into customary law. The For the more than 500 years since the arrival body of the customary norms that regulate

aim is to rebuild trust in the criminal justice sys- of the Spanish conquistadors Guatemala’s in- indigenous community life as well as the

tem and respect for the rule of law and to rec- digenous people have suffered violent sub- lack of access that the indigenous popula-

ognize customary laws. The challenge lies in ordination and exclusion. The armed internal tion has to the resources of the national jus-

conflict that lasted from 1960 until the sign- tice system, have caused negation of rights,

integrating common and customary law in line

ing of the peace accords in 1996 was partic- discrimination and marginalization”.

with the new constitution, enshrining such prin- ularly devastating. Indigenous people, The government and the opposition

ciples as gender equality. This harmonization constituting more than half the population, have agreed to:

process marks a major step in South Africa’s endured massacres and gross violations of • Recognize the management of internal

enormous task of legal reform. The first step was human rights. The military dictatorship of issues of the indigenous communities

1970–85 undermined the independence of according to their own judicial norms.

repealing apartheid laws. Next was reconsti- local community authorities. • Include cultural considerations in the

tuting the Law Commission, dominated by con- Little surprise, then, that rural com- practice of law.

servative judges of the old regime. Now South munities lost faith in the judicial system and • Develop a permanent programme for

Africa must shape new laws to govern a new so- the rule of law. Public lynchings became judges and members of the Public Min-

the alternative to the formal justice system, istry on the culture and identity of in-

cial order.

notorious for its inability to sentence the digenous people.

Customary law is often the only form of perpetrators of crimes and its tendency to • Ensure free judicial advisory services

justice known to many South Africans. About release criminals through a corrupt bail tra- for people with limited resources.

half the population lives in the countryside, dition. The political establishment cynically • Offer free services for interpretation of

where traditional courts administer customary misrepresents the lynchings as the tradi- judicial proceedings into indigenous

tional practices of indigenous people. languages.

law in more than 80% of villages.34 These courts, The 1996 accords acknowledged the These developments are first steps in

also found in some urban townships, deal with need for genuine reform with commitments acknowledging the distinct cultures of in-

petty theft, property disagreements and do- to acknowledge traditional Mayan law and digenous people in Guatemala. The chal-

mestic affairs—from marriage to divorce to in- authority. The Accord on Indigenous Iden- lenge now is to develop the customary

tity and Rights, for example, states that “the systems in a way consistent with human

heritance. Justice is swift and cheap as the courts lack of knowledge by the national legislative rights and gender equality.

are run with minimal formalities in venues close Source: Buvollen 2002.

to the disputants’ homes and charge less than

BUILDING MULTICULTURAL DEMOCRACIES 59

POLICIES ON THE USE OF MULTIPLE LANGUAGES the International Covenant on Civil and Politi-

cal Rights. Especially important are the rights to

By choosing one or a few languages over oth- freedom of expression and equality. Freedom of

ers, a state often signals the dominance of those expression and the use of a language are insep-

for whom the official language is their mother arable. This is the most obvious example of the

tongue. This choice can limit the freedom of importance of language in matters of law. For ex-

many non-dominant groups—feeding inter- ample, until 1994 members of the Kurd minor-

group tensions (see chapter 2). It becomes a way ity in Turkey were prohibited by law from using

of excluding people from politics, education, ac- their language in public. Reform of this law was

cess to justice and many other aspects of civic an important element in the government’s re-

life. It can entrench socio-economic inequalities sponse to the demands of the Kurdish minority.

Language conflicts can be between groups. It can become a divisive po- In 2002 the Turkish Parliament passed legisla-

litical issue, as in Sri Lanka where, in place of tion allowing private institutions to teach the

managed by providing

English, Sinhala (spoken by the majority) was language of the sizeable Kurdish minority, and

some spheres in which made the only official language in 1956 despite the first Kurdish language teaching centre opened

the opposition of the Tamil minority, who in March 2004 in Batman, in the southeast.

minority languages are

wanted both Sinhala and Tamil recognized. Experience around the world shows that

used freely and by giving While it is possible and even desirable for a plural language policies can expand opportu-

state to remain “neutral” on ethnicity and reli- nities for people in many ways, if there is a de-

incentives to learn other

gion, this is impractical for language. The citizenry liberate effort to teach all citizens some of the

languages, especially a needs a common language to promote mutual un- country’s major languages (box 3.7). Very often

derstanding and effective communication. And what multilingual countries need is a three-

national or official

no state can afford to provide services and offi- language formula (as UNESCO recommends)

language cial documents in every language spoken on its that gives public recognition to the use of three

territory. The difficulty, however, is that most languages:

states, especially in the developing world and • One international language—in former colo-

Eastern Europe, are multilingual—and they are nial countries this is often the official lan-

the focus of much of the discussion here. Once guage of administration. In this era of

again, multicultural policies are needed. globalization all countries need to be pro-

In multilingual societies plural language ficient in an international language to par-

policies provide recognition to distinct linguis- ticipate in the global economy and networks.

tic groups. Plural language policies safeguard the • One lingua franca—a local link language

parallel use of two or more languages by saying, facilitates communication between different

in essence, “Let us each retain our own lan- linguistic groups such as Swahili in East

guage in certain spheres, such as schools and uni- African countries, where many other lan-

versities, but let us also have a common language guages are also spoken.

for joint activities, especially in civic life.” • Mother tongue—people want and need to

Language conflicts can be managed by provid- be able to use their mother tongue when it

ing some spheres in which minority languages is neither the lingua franca nor the interna-

are used freely and by giving incentives to learn tional language.

other languages, especially a national or official Countries need to recognize all three as of-

language. This can be promoted by an appro- ficial languages or at least recognize their use and

priate social reward structure, such as by mak- relevance in different circumstances, such as in

ing facility in a national language a criterion for courts or schools. There are many versions of

professional qualification and promotion. such three-language formulas, depending on

There is no universal “right to language”.36 the country.

But there are human rights with an implicit The main questions that states face on lan-

linguistic content that multilingual states must ac- guage policy relate to the language of instruc-

knowledge in order to comply with their inter- tion in schools and the language used in

national obligations under such instruments as government institutions.

60 HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2004

BOX 3.7

Multilingual education in Papua New Guinea

Nestled between the South Pacific Ocean and No statistical study has been done, but their schools to the local language had to agree

the Coral Sea, Papua New Guinea is the most there is abundant anecdotal evidence that chil- to build new facilities, assist in the life of the