Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Cahoots One Pager

Caricato da

Sinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Cahoots One Pager

Caricato da

Sinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneCopyright:

Formati disponibili

August 2020

The Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets (CAHOOTS) Act

As the country grapples with advancing racial justice, reducing police brutality, addressing mental

health and substance use disorder (SUD) needs and reimagining public safety, Oregon has offered a

model for moving forward. For over 30 years, Eugene, Oregon’s White Bird Clinic has led the way in

using health care, rather than law enforcement, to respond to individuals who are experiencing a mental

health or SUD related crisis. The innovative Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets, or

CAHOOTS, model dispatches mobile teams of health care and crisis workers to meet Oregonians where

they are and provide the care and services they need instead of immediately involving law enforcement.

Using the lessons outlined by White Bird Clinic and similar programs across the nation, Senators Ron

Wyden and Catherine Cortez Masto have introduced the Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets

(CAHOOTS) Act to help states adopt their own mobile crisis response models through support from

Medicaid.

The CAHOOTS Act:

Grants states enhanced federal Medicaid funding (a 95% federal match) for three years to

provide qualifying community-based mobile crisis services to individuals experiencing a mental

health or SUD crisis. The Act also provides $25 million for planning grants to states to help

establish mobile crisis programs.

Funds multidisciplinary mobile crisis teams that are available 24/7, every day of the year, and

trained in trauma-informed care, de-escalation, and harm reduction to provide voluntary

assessment and stabilization services for individuals in crisis, as well as coordination and

referrals to follow-up care and wraparound services, including housing assistance. Teams must

be able to provide or coordinate transportation to help individuals reach their next step in care.

Requires mobile crisis teams to partner with key community resources to facilitate referral and

coordination efforts. For example, teams must have relationships with behavioral health

providers, crisis respite centers, housing assistance providers such as public housing authorities,

and other organizations and agencies that provide social services.

Directs mobile crisis teams to be connected to regional hotlines and emergency medical service

systems. Mobile crisis teams must not be operated by or affiliated with state or local law

enforcement agencies, though teams may coordinate with law enforcement if appropriate.

Requires states to conduct a robust evaluation of the impact of mobile crisis services on

emergency room visits, the involvement of law enforcement in mental health or SUD events,

diversion from jails, and other outcomes. States must also report on the models and programs

they design, including how people are connected to care following the delivery of mobile crisis

services. States would also be required to report on the demographic information of the

individuals their teams help in order to identify and help address health disparities.

Requires the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to summarize states’ results and

lift-up best practices for delivering effective mobile crisis intervention services.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Social Security Expansion Act 2023Documento48 pagineSocial Security Expansion Act 2023Sinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- To End A Crisis: Vision For BC Drug PolicyDocumento13 pagineTo End A Crisis: Vision For BC Drug PolicyCDPCNessuna valutazione finora

- Swedish Medical Center Patient LetterDocumento2 pagineSwedish Medical Center Patient LetterMichael_Lee_RobertsNessuna valutazione finora

- 1.advocacy Campaign For People Suffering From Substance Abuse1.EditedDocumento11 pagine1.advocacy Campaign For People Suffering From Substance Abuse1.EditedBrenda MogeniNessuna valutazione finora

- Subsyems Policies in USADocumento13 pagineSubsyems Policies in USAWanjikuNessuna valutazione finora

- Study On Empowering Youth and Adults To Overcome Mental Health Hardships Using A Web ApplicationDocumento6 pagineStudy On Empowering Youth and Adults To Overcome Mental Health Hardships Using A Web ApplicationInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Austrilia Health CareDocumento23 pagineAustrilia Health CarePandaman PandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Health Care Equity Tool Kit for Developing Winning PolicyDocumento25 pagineHealth Care Equity Tool Kit for Developing Winning PolicyDenden Alicias100% (1)

- Police Mental Health CollaborationsDocumento24 paginePolice Mental Health CollaborationsEd Praetorian100% (3)

- Anemia FetalDocumento9 pagineAnemia FetalCarolina Cabrera CernaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bangladesh's Healthcare Delivery ExplainedDocumento50 pagineBangladesh's Healthcare Delivery ExplainedDip Ayan MNessuna valutazione finora

- ANTENATAL Case Study FormatDocumento4 pagineANTENATAL Case Study FormatDelphy Varghese100% (8)

- Patients Rights, Patients, Hospital Patient Rights, HospitalDocumento23 paginePatients Rights, Patients, Hospital Patient Rights, HospitalDr Vijay Pratap Raghuvanshi100% (3)

- Presentation On Health Care System ModelsDocumento37 paginePresentation On Health Care System ModelsTashi Makpen100% (1)

- Department of Health - Women and Children Protection Program - 2011-10-19Documento12 pagineDepartment of Health - Women and Children Protection Program - 2011-10-19daryl ann dep-asNessuna valutazione finora

- CAHOOTS One-Pager 117th CongressDocumento1 paginaCAHOOTS One-Pager 117th CongressSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Hsci 6250Documento4 pagineHsci 6250api-642711495Nessuna valutazione finora

- Module 4 2Documento4 pagineModule 4 2api-642701476Nessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 5 Task 3Documento30 pagineUnit 5 Task 3Abigail Adjei A.HNessuna valutazione finora

- Safety Now - Budget Letter 04.11.22Documento6 pagineSafety Now - Budget Letter 04.11.22Jessica BrandNessuna valutazione finora

- ExhibitG3-Missouri Reentry ProcessDocumento14 pagineExhibitG3-Missouri Reentry ProcessDiana K. CoricNessuna valutazione finora

- NDIS essay outlines support for vulnerable groupsDocumento5 pagineNDIS essay outlines support for vulnerable groupsBikash sharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- NCM 104 Week 3Documento15 pagineNCM 104 Week 3Nathan Lloyd SangcapNessuna valutazione finora

- AHC in NEJM PDFDocumento4 pagineAHC in NEJM PDFiggybauNessuna valutazione finora

- Metro Human Rights Commission ReportDocumento27 pagineMetro Human Rights Commission ReportUSA TODAY NetworkNessuna valutazione finora

- DRRMDocumento8 pagineDRRMhanimonrealNessuna valutazione finora

- Health Reform in 2013Documento3 pagineHealth Reform in 2013alessandrabrooks646Nessuna valutazione finora

- Wny Hospital Medical Surge Planning For Mass Casualty IncidentsDocumento43 pagineWny Hospital Medical Surge Planning For Mass Casualty IncidentskbonairNessuna valutazione finora

- Policy Implementation Analysis: Reverse Mass Incarceration Act of 2019Documento14 paginePolicy Implementation Analysis: Reverse Mass Incarceration Act of 2019Jackson MwaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Module SummaryDocumento3 pagineModule SummaryKen EdwardsNessuna valutazione finora

- Irregular MigrantsDocumento2 pagineIrregular MigrantsSILVIA MARIA MORALES GOMEZNessuna valutazione finora

- Public Administration and HealthDocumento6 paginePublic Administration and HealthMpho KulembaNessuna valutazione finora

- Agency PaperDocumento13 pagineAgency Paperapi-272668024Nessuna valutazione finora

- PHC ManualDocumento92 paginePHC ManualRory Rose PereaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2022 End of Session Report January 1 Effective DateDocumento6 pagine2022 End of Session Report January 1 Effective DateAbby KousourisNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment 10 PageDocumento12 pagineAssignment 10 PageDennis waitiki muiruriNessuna valutazione finora

- OVSJG 2022 Performance Oversight Hearing TestimonyDocumento9 pagineOVSJG 2022 Performance Oversight Hearing TestimonyCami MondeauxNessuna valutazione finora

- ContemporaryDocumento7 pagineContemporarylynie cuicoNessuna valutazione finora

- Doh - Nohdz ReportDocumento5 pagineDoh - Nohdz ReportDhonnalyn Amene CaballeroNessuna valutazione finora

- LSA-DN LTC Recommendations FINALDocumento2 pagineLSA-DN LTC Recommendations FINALLSA-DNNessuna valutazione finora

- Victim assistance programmes assessed and resources evaluatedDocumento8 pagineVictim assistance programmes assessed and resources evaluatedBersekerNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparison Between RTE and Draft On Right To Health BillDocumento5 pagineComparison Between RTE and Draft On Right To Health BillSaurabh KushwahaNessuna valutazione finora

- Slide 1: Disaster Recovery Plan For Vila Health: Berke, Et Al., 2014)Documento7 pagineSlide 1: Disaster Recovery Plan For Vila Health: Berke, Et Al., 2014)Ravi KumawatNessuna valutazione finora

- Resource and Service Restriction For Political ControlDocumento2 pagineResource and Service Restriction For Political Controlapi-725128015Nessuna valutazione finora

- Washington Drug Decriminalization CampaignDocumento2 pagineWashington Drug Decriminalization CampaignMarijuana MomentNessuna valutazione finora

- Public Health TerminologyDocumento17 paginePublic Health Terminologymohammed RAFINessuna valutazione finora

- Case StudyDocumento6 pagineCase StudyLoreah Kate D. DacanayNessuna valutazione finora

- President Biden Executive Order On PolicingDocumento47 paginePresident Biden Executive Order On Policingepraetorian100% (1)

- 2013 LSA-DN Policy and Advocacy PrioritiesDocumento2 pagine2013 LSA-DN Policy and Advocacy PrioritiesLSA-DNNessuna valutazione finora

- Mandate & MissionDocumento10 pagineMandate & MissionRyan Michael OducadoNessuna valutazione finora

- Text For Consecutive TranslationDocumento2 pagineText For Consecutive TranslationInaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ten Essential Public Health Services-1Documento3 pagineTen Essential Public Health Services-1Asia AmirNessuna valutazione finora

- Soc Reint EngDocumento61 pagineSoc Reint EngJuan SorianoNessuna valutazione finora

- VPD - Mental Health StrategyDocumento41 pagineVPD - Mental Health StrategyCKNW980Nessuna valutazione finora

- Group Project 1 Post DMHDocumento9 pagineGroup Project 1 Post DMHSteve Premier NaiveNessuna valutazione finora

- SIMUN - WELLFAREDocumento1 paginaSIMUN - WELLFARETri PhamNessuna valutazione finora

- Week 2 NotesDocumento5 pagineWeek 2 Notesu21698245Nessuna valutazione finora

- HEALTH ORGANIZATION DISASTER PLANNING AND RESPONSEDocumento11 pagineHEALTH ORGANIZATION DISASTER PLANNING AND RESPONSEMcaby Rose FrediexNessuna valutazione finora

- Adsız DokümanDocumento7 pagineAdsız Dokümangoldcagan2009Nessuna valutazione finora

- Regional Emergency Planning For Healthcare Facilities: Regional AgreementsDocumento4 pagineRegional Emergency Planning For Healthcare Facilities: Regional AgreementsMax GeNessuna valutazione finora

- Strategic Plan For WebDocumento34 pagineStrategic Plan For WebTexas WatchdogNessuna valutazione finora

- 8606 2nd Assignment RabiaDocumento28 pagine8606 2nd Assignment RabiaRabia BasriNessuna valutazione finora

- Ending Discrimination Healthcare Settings enDocumento4 pagineEnding Discrimination Healthcare Settings enTee Kok KeongNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary of HB 520 (As Passed by The House On March 2, 2023)Documento8 pagineSummary of HB 520 (As Passed by The House On March 2, 2023)WTVCNessuna valutazione finora

- DRL FY2020 The Global Equality Fund NOFODocumento23 pagineDRL FY2020 The Global Equality Fund NOFORuslan BrvNessuna valutazione finora

- Coquille RiverFest Car Show Press Release and SponsorsDocumento1 paginaCoquille RiverFest Car Show Press Release and SponsorsSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- DCFD Push-In AnnouncementDocumento1 paginaDCFD Push-In AnnouncementSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Postgame Notes - Oregon vs. StanfordDocumento1 paginaPostgame Notes - Oregon vs. StanfordSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Springfield City Council Ward 4 Q & A - 2023Documento2 pagineSpringfield City Council Ward 4 Q & A - 2023Sinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Proposed Measure 20-340Documento2 pagineProposed Measure 20-340Sinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- 12-10-2022 - BPD OIS - Press ReleaseDocumento3 pagine12-10-2022 - BPD OIS - Press ReleaseSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- 2023 Council Vacancy Transition DocumentDocumento1 pagina2023 Council Vacancy Transition DocumentSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Nautical Chart Showing Tillamook BayDocumento1 paginaNautical Chart Showing Tillamook BaySinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Linn County District Attorney ReleaseDocumento3 pagineLinn County District Attorney ReleaseSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Employment in Oregon - January 2023Documento5 pagineEmployment in Oregon - January 2023Sinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Postgame Notes - Women's Basketball: Washington vs. Oregon - Pac-12 Tournament First RoundDocumento1 paginaPostgame Notes - Women's Basketball: Washington vs. Oregon - Pac-12 Tournament First RoundSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Pac-12 Tournament - Stanford 76, Oregon 65Documento29 paginePac-12 Tournament - Stanford 76, Oregon 65Sinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Todd C. Munsey Retires From Adapt BoardDocumento1 paginaTodd C. Munsey Retires From Adapt BoardSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- BAH Press Release (Feb. 20, 2023)Documento1 paginaBAH Press Release (Feb. 20, 2023)Sinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Security Expansion Act One Pager FinalDocumento3 pagineSocial Security Expansion Act One Pager FinalSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- 2022 City of Springfield Bond Measure Annual ReportDocumento5 pagine2022 City of Springfield Bond Measure Annual ReportSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Coos Bay Public Library Job Fair - March 15, 2023Documento1 paginaCoos Bay Public Library Job Fair - March 15, 2023Sinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- North Bend School District #13 Board Vacancies (2023)Documento3 pagineNorth Bend School District #13 Board Vacancies (2023)Sinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Umpqua National Forest Fee ProposalDocumento2 pagineUmpqua National Forest Fee ProposalSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Senate Resolution 349 Honoring Contributions of The Ritchie BoysDocumento4 pagineSenate Resolution 349 Honoring Contributions of The Ritchie BoysSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Road Closure at 9th Ave.Documento1 paginaRoad Closure at 9th Ave.Sinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- 2022-23 Reedsport City Council ApplicationDocumento2 pagine2022-23 Reedsport City Council ApplicationSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Lebanon Fire District Groundbreaking InviteDocumento1 paginaLebanon Fire District Groundbreaking InviteSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

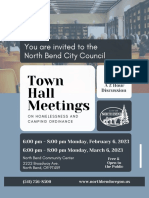

- North Bend Town Hall Meetings On HomelessnessDocumento1 paginaNorth Bend Town Hall Meetings On HomelessnessSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Rose Complaint and ResponseDocumento33 pagineRose Complaint and ResponseSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Art SubmissionsDocumento1 paginaArt SubmissionsSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- 2023 North Bend State of The City AddressDocumento30 pagine2023 North Bend State of The City AddressSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Application For City CouncilorDocumento1 paginaApplication For City CouncilorSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- Overdose Press Release 01-06-2023Documento2 pagineOverdose Press Release 01-06-2023Sinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNessuna valutazione finora

- مزاولة مهنة - طب أسنان نوفمبر 2020Documento5 pagineمزاولة مهنة - طب أسنان نوفمبر 2020وردة صبرNessuna valutazione finora

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocumento3 pagineDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesRosalie Navales LegaspiNessuna valutazione finora

- Pathology Situational EthicsDocumento28 paginePathology Situational Ethicsmohitsingla_86Nessuna valutazione finora

- Prof. Erica Wood - APEC PBMDocumento46 pagineProf. Erica Wood - APEC PBMbudi darmantaNessuna valutazione finora

- PENGARUH PENDIDIKAN KESEHATAN TERHADAP PENGETAHUAN KANKER OVARIUMDocumento7 paginePENGARUH PENDIDIKAN KESEHATAN TERHADAP PENGETAHUAN KANKER OVARIUMSalsabila DindaNessuna valutazione finora

- SOAP Documentation for Mr. BrownDocumento2 pagineSOAP Documentation for Mr. BrownShamyahNessuna valutazione finora

- Ebr2 CunananDocumento2 pagineEbr2 CunananAbbyNessuna valutazione finora

- Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines On The Treatment and Management of Pa - Tients With COVID-19, 14 MARTIE 2023 PDFDocumento56 pagineInfectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines On The Treatment and Management of Pa - Tients With COVID-19, 14 MARTIE 2023 PDFdavid mangaloiuNessuna valutazione finora

- Garces, Sherlyn Lfdweek1Documento1 paginaGarces, Sherlyn Lfdweek1Sherlyn Miranda GarcesNessuna valutazione finora

- Notification Letter EnglishDocumento1 paginaNotification Letter EnglishJovele OctobreNessuna valutazione finora

- Factors Affecting Health Care DemandDocumento5 pagineFactors Affecting Health Care DemandRochelle Anne Abad BandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Effectiveness of Communication Board On Level of Satisfaction Over Communication Among Mechanically Venitlated PatientsDocumento6 pagineEffectiveness of Communication Board On Level of Satisfaction Over Communication Among Mechanically Venitlated PatientsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Art 6Documento10 pagineArt 6Velazquez Rico Cinthya MontserrathNessuna valutazione finora

- The Health Bank (THB) Connected Care Program A Pilot Study of Remote Monitoring For The Management of Chronic Conditions Focusing On DiabetesDocumento5 pagineThe Health Bank (THB) Connected Care Program A Pilot Study of Remote Monitoring For The Management of Chronic Conditions Focusing On DiabetesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- BP ManagementDocumento305 pagineBP Managementchandra9000Nessuna valutazione finora

- DR AnupamaDocumento4 pagineDR AnupamaArchana SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Name: - Score: - Teacher: - DateDocumento2 pagineName: - Score: - Teacher: - DatePauline Erika CagampangNessuna valutazione finora

- Chorioamnionitis by DR Simon ByonanuweDocumento31 pagineChorioamnionitis by DR Simon ByonanuweDr Simon ByonanuweNessuna valutazione finora

- Factors Affecting Utilisation of Antenatal Care Services Among Pregnant Women Attending Kitagata Hospital, Sheema District UgandaDocumento8 pagineFactors Affecting Utilisation of Antenatal Care Services Among Pregnant Women Attending Kitagata Hospital, Sheema District UgandaKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNessuna valutazione finora

- Personal safety in sportsDocumento8 paginePersonal safety in sportsDayrille Althea Liwag Yalung100% (2)

- NS60167W Formative Exam Ref ListDocumento2 pagineNS60167W Formative Exam Ref ListNIAZ HUSSAINNessuna valutazione finora

- Healthways WholeHealth LivingDocumento1 paginaHealthways WholeHealth LivingHealthways, Inc.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Approach To The Patient With Postmenopausal Uterine Bleeding - UpToDateDocumento18 pagineApproach To The Patient With Postmenopausal Uterine Bleeding - UpToDateCHINDY REPA REPANessuna valutazione finora

- A Standardized Endodontic Technique Utilizing Newly Designed Instruments and Filling Materials PDFDocumento9 pagineA Standardized Endodontic Technique Utilizing Newly Designed Instruments and Filling Materials PDFCristian FernandoNessuna valutazione finora

- Career Research and Essay 1Documento13 pagineCareer Research and Essay 1alehadroNessuna valutazione finora