Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Case Study 3 PDF

Caricato da

shynaTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Case Study 3 PDF

Caricato da

shynaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

of having poor results.

Managers of firms with bad news would have incentives not

to report. However, they would also have the incentive to report their bad news, to

maintain credibility in effective markets where their shares are traded. Assuming these

incentives to signal information to capital markets, signalling theory predicts that firms

will disclose more information than is demanded.

The logical consequence of signalling theory is that there are incentives for all

managers to signal expectations of future profits because, if investors believe the signals,

share prices will increase and the shareholders (and managers acting in their interests)

will benefit. However, one problem therefore arises: how does a firm ensure that its

signal is seen as credible by investors, given that other firms will also try to signal 'good

news'? For a signal via the accounts to be credible to users, that signal must not be

easily and costlessly replicated by another firm. Costs can include the long-term loss of

credibility if actual performance does not match the level that has been signalled via

the way in which profitability has been represented in the accounts.

One way is to provide a;:!.9i1iQnaLcr.edib.ility..JOeam~.Qgs signal by Qrovidlugill:ll.i.d.end

~gIlals. '1'hese are costly as they involve cash payouts to sha.£.eholders. Furthermore,

firms generally snroOththeir dividends and managers are very reluctant to re..duce

-----

dividends. Thus, if di;iQends increase, maOARers are reasonably sure that they will not

s,ubsequently decrease. So the increase can create an expectation of future increased

profits sufficient to support the higher level of dividends into the future .

. Research into signalling incentives includes studies that investigate why firms

voluntarily disclose bad news, reduce and increase dividends, smooth earnings

and revalue and impair assets, and recognise internally generated assets. Theory

in action 11.3 provides an example of how one firm has signalled its e.,xpectations

regarding future profitability.

What do profits signal?

Navitas e arniJ gs soar in slump

by Sara Rich

Education provider Navitas has achieved a 32 per c'ent rise in full-year profit and says the

global financial crisis may be working in its favour, with another year of double-digit earnings

growth expected.

Net profit for the year ended june 30 climbed to $49.2 million compared with $37.4 m a

year ago, while revenue rose 36 per cent to $470.7 m.

The Perth-based company provides university pathway programs for domestic and

international students, as well as language training, work-force education and student

recruitment services.

Navitas chief executive Rod jones said the company, which had low debt levels and good

cashflow, had not been affected by the downturn and that student numbers were at record

highs. Last financial year, the number of students in Navitas's university programs surged

26 per cent to about 20 000. In total, there are about 45 000 domestic and overseas students

using the education provider's services,

"When employment opportunities reduce, many students turn back to education," Mr jones

said.

He said this had helped drive a 22 per cent increase in earnings before interest, tax,

depreciation and amortisation to $77.1 m for the company.

Earnings per share climbed 32 per cent to 14.3c, while operating cashflow was up 33 per

centat$104.3 m.

Navitas declared a final dividend of 8.8c, up from 6.2c last year, taking the full-year

payment to 14.3c, compared with the previous year's 10. 9c.

PART 3 Accounting and research

Last financial year was the fifth year in a row that Navitas achieved more than 10 per cent

growth in earnings, revenue and operating cashflow.

The compan y's share price climbed 5.45 per cent, or 15c yesterday to $2.90.

Source : Excerp ts irom Th e Australian , S August 2009 , p. 24, www .thea ustralia n.conl .a u.

Questions

1. Navitas's announcement of soaring profit is a strong signal of the firm 's earnings prospects.

Other comments in the article reinforce that signal. What could Navitas do in relation to

its profits to strengthen the signal even further? Explain your answer.

2. What factors might increase or decrease the credibility of the signal provided by Navitas's

announcement and press attention ?

3. What do you expect will be the impact of the 'soaring' profits oil management compensation

contracts of Navitas?

POLITICAL PROCESSES

Positive accounting theory also models the political process involving the reJationsb.ip

between the firm anL a.th.e.Lpgrties interested in the firm.. such .as.-government,

trade unions and community grQ!!Qs. As in the context of debt and management

com ensatio~contractiI1g, accounting is important in the political process as one of

the sources of information about firms.

The major difference between the pglitical market and the capital market is that there

js generally less demand, and therefore less incentive, for the productio n of information

in political markets. Economic analysis suggests that this results from the lower marginal

benefit to individuals in the political process, because it is harder for individuals or

groups to capture benefits from that information. 2G There are high information costs to

individuals, heterogeneity (diversity) of interests, and organisational costs.

High information costs arise because in the political environment, the probability

that one individual's actions will affect that person's wealth is small. Each individual is

only one of many 'voters' in the political arena, there are many political decisions being

made at any time, and many of them are likely to affect that individual's wealth. To be

informed on all the issues is unlikely to be cost-beneficial given the low probability that

the individual will affect the political outcome. PoJiticaLc..o.s.ts can be diffused among

imli-Yid.u<!ls. Take for example, the political decision to increase the price of milk by

. 10 cents per litre. The costs are diffused across consumers but the total amount received

by the milk corporation is substantial. The lobbying cost/ benefit for individuals is high .

If consumers form interest groups and group lobby then this increases the likelihood

of a particular political outcome. However, heterogeneity of interests within the group

means that group actions will not necessarily be in a particular individual's interests.

further, the formation of interest groups is costly. Not only must group members

incur the search costs of identifying each other to form the group, but the group incurs

additional costs to lobby for its cause, inform its members, and so on. These transaction

costs mean that individuals either will choose to stay rationally uninformed or if the

individual gains are high enough they will form interest groups to capture economies of

scale in the information-generation process, despite the organisational costs of doing so.

The amount of information generated for political and social purposes will therefore

depend on the diffusive effects of government policy and the transaction costs of

effective 10bbying.27 Hence, because of the greater information costs, diffused rewards,

and high monitoring costs, there is greater scope for residual opportunism to occur.

Positive accounting theorists often cite the 1931 and 1933 Securities Acts in the

United States which followed the 1929 stock market crash as an example of political

CHAPTER 11 Positive theory of accounting polic y and disclosu re 377

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Is Financial Leverage Good For Shareholders?: Gregory V. Milano Joseph TheriaultDocumento2 pagineIs Financial Leverage Good For Shareholders?: Gregory V. Milano Joseph TheriaultFELIPE ANDRES MANUEL ALEJ AILLAPAN VALDEBENITONessuna valutazione finora

- BCG Corporate Treasury Insights 2015Documento19 pagineBCG Corporate Treasury Insights 2015thesrajesh7120100% (1)

- Forex Systems: Types of Forex Trading SystemDocumento35 pagineForex Systems: Types of Forex Trading SystemalypatyNessuna valutazione finora

- Investor RelationsDocumento43 pagineInvestor RelationsSalman Alfarisyi Lesmana, S.I.Kom., M.MNessuna valutazione finora

- 4 Common Types of Construction ContractsDocumento12 pagine4 Common Types of Construction Contractsharshit sorthiyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporate Reporting Practices in IndiaDocumento25 pagineCorporate Reporting Practices in IndiaClary Dsilva67% (3)

- Bsbcrt611 Apply Critical Thinking For Complex Problem Solving Assessment Task 2Documento9 pagineBsbcrt611 Apply Critical Thinking For Complex Problem Solving Assessment Task 2Ana Martinez75% (8)

- Value-based financial management: Towards a Systematic Process for Financial Decision - MakingDa EverandValue-based financial management: Towards a Systematic Process for Financial Decision - MakingNessuna valutazione finora

- Activity Sheets AE Week 1Documento6 pagineActivity Sheets AE Week 1Dotecho Jzo EyNessuna valutazione finora

- Manneh NaserDocumento11 pagineManneh NaseramandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Next 4Documento10 pagineNext 4Nurhasanah Asyari100% (1)

- Importance of Ease of Doing BussinessDocumento15 pagineImportance of Ease of Doing BussinessAkash kumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Thesis On Debt FinancingDocumento8 pagineThesis On Debt Financingheidimaestassaltlakecity100% (2)

- TRANCENDETCAPITALGLODANDocumento6 pagineTRANCENDETCAPITALGLODANNguyễn Thanh HuyềnNessuna valutazione finora

- (Review Artikel Jurnal) HedgingDocumento38 pagine(Review Artikel Jurnal) HedgingGusi Putu Pratita IndiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Term Paper of Financial ManagementDocumento6 pagineTerm Paper of Financial Managementafmzmxkayjyoso100% (1)

- A Study To Analyse Effect of Corporate Actions On Stock Market Returns of Selected Indian IT CompaniesDocumento22 pagineA Study To Analyse Effect of Corporate Actions On Stock Market Returns of Selected Indian IT CompaniesAnkit SarkarNessuna valutazione finora

- 2011SU Features EcclesSaltzmanDocumento7 pagine2011SU Features EcclesSaltzmanBrankoNessuna valutazione finora

- Finance Dissertation SampleDocumento8 pagineFinance Dissertation SampleSomeoneToWriteMyPaperForMeEvansville100% (1)

- The Case For Stakeholder Capitalism VF 1Documento8 pagineThe Case For Stakeholder Capitalism VF 1Lavandería RaysaNessuna valutazione finora

- Emerging Trends in Corporate Governance in 2022Documento12 pagineEmerging Trends in Corporate Governance in 2022khushwantNessuna valutazione finora

- FM WCM AssignmentDocumento11 pagineFM WCM AssignmentAlen AugustineNessuna valutazione finora

- Economic DevelopmentDocumento2 pagineEconomic DevelopmentJoanah TayamenNessuna valutazione finora

- Burget Paints Financial Report Summary and InsightsDocumento5 pagineBurget Paints Financial Report Summary and InsightscoolNessuna valutazione finora

- The Case For Stakeholder CapitalismDocumento8 pagineThe Case For Stakeholder CapitalismPatricia GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Financial Leverage On Dividend Policy of Selected Manufacturing Firms in NigeriaDocumento12 pagineImpact of Financial Leverage On Dividend Policy of Selected Manufacturing Firms in NigeriaMayaz AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- Firm's Environment, Governance and Strategy: Strategic Financial ManagementDocumento14 pagineFirm's Environment, Governance and Strategy: Strategic Financial ManagementAnish MittalNessuna valutazione finora

- More Than RM New Layout 1Documento12 pagineMore Than RM New Layout 1manojraghunath88Nessuna valutazione finora

- M. Mustujab Ali ROLL NO 1512-115015 BBA (Evening) Service Marketing-2Documento5 pagineM. Mustujab Ali ROLL NO 1512-115015 BBA (Evening) Service Marketing-2Ali MustujabNessuna valutazione finora

- A Usa Grenee Sfa 2004Documento33 pagineA Usa Grenee Sfa 2004ridwanbudiman2000Nessuna valutazione finora

- Contemporary Issues in Finance - International Aspects of Corporate Finance - Jerralyn AlvaDocumento5 pagineContemporary Issues in Finance - International Aspects of Corporate Finance - Jerralyn AlvaJERRALYN ALVANessuna valutazione finora

- Dissertation Report of FinanceDocumento5 pagineDissertation Report of FinanceCustomWrittenPapersClarksville100% (1)

- Research Paper in Finance ManagementDocumento8 pagineResearch Paper in Finance Managementggsmsyqif100% (1)

- Ishrat Husain: Usiness N HE EW NvironmentDocumento6 pagineIshrat Husain: Usiness N HE EW NvironmentRaheel PunjwaniNessuna valutazione finora

- The Economic Environment: Course: ECON6017003 - ECONOMICS THEORY Effective Period: Even Semester 2022Documento18 pagineThe Economic Environment: Course: ECON6017003 - ECONOMICS THEORY Effective Period: Even Semester 2022Stivon LayNessuna valutazione finora

- Finance Dissertation StructureDocumento5 pagineFinance Dissertation StructurePayToDoPaperNewHaven100% (1)

- I CreateDocumento9 pagineI CreateRealGenius (Carl)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Interindustry Dividend Policy Determinants in The Context of An Emerging MarketDocumento6 pagineInterindustry Dividend Policy Determinants in The Context of An Emerging MarketChaudhary AliNessuna valutazione finora

- Case #12: What Are We Really Worth? (Valuation of Common Stock)Documento7 pagineCase #12: What Are We Really Worth? (Valuation of Common Stock)Julliena BakersNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporate Finance CourseworkDocumento4 pagineCorporate Finance Courseworkf5d7ejd0100% (2)

- Research Paper in Financial ManagementDocumento6 pagineResearch Paper in Financial Managementgw10yvwg100% (1)

- Q1 2023 Fintech Payments Public Comp Sheet and Valuation GuideDocumento25 pagineQ1 2023 Fintech Payments Public Comp Sheet and Valuation GuidecheungNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample ReportDocumento33 pagineSample ReportPubg KillerNessuna valutazione finora

- Management Accounting Concepts and TechniquesDocumento277 pagineManagement Accounting Concepts and TechniquesCalvince OumaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ass#2 Values, Goals, PerformanceDocumento3 pagineAss#2 Values, Goals, PerformanceGian Kaye AglagadanNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter Six International Transparency and DisclosureDocumento11 pagineChapter Six International Transparency and DisclosuremonikNessuna valutazione finora

- Individual Assignment: Name Id Number K.K.Kavitharane A/P Kuppusamy 1207201012Documento8 pagineIndividual Assignment: Name Id Number K.K.Kavitharane A/P Kuppusamy 1207201012Tha RaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Are Profit Maximizers Wealth CreatorsDocumento36 pagineAre Profit Maximizers Wealth Creatorskanika5985Nessuna valutazione finora

- Merger and Acquisition of Financial Institutions: Page - 1Documento8 pagineMerger and Acquisition of Financial Institutions: Page - 1Mishthi SethNessuna valutazione finora

- Finance Dissertation Report PDFDocumento5 pagineFinance Dissertation Report PDFOrderCustomPaperUK100% (1)

- Group Project Far 661Documento19 pagineGroup Project Far 661azri2701Nessuna valutazione finora

- UEU Journal - Income Smoothing Anaysis in Snacks IndustryDocumento14 pagineUEU Journal - Income Smoothing Anaysis in Snacks Industrykanina.putri4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Five Criteria For IMS DecisionsDocumento5 pagineFive Criteria For IMS DecisionsKim TranNessuna valutazione finora

- Debt On Profitability FinalDocumento65 pagineDebt On Profitability FinalRexmar Christian BernardoNessuna valutazione finora

- Dissertation Financial AnalysisDocumento5 pagineDissertation Financial AnalysisCanSomeoneWriteMyPaperRiverside100% (1)

- M & ADocumento9 pagineM & APriyadarshini SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample Thesis Financial AnalysisDocumento5 pagineSample Thesis Financial AnalysisTye Rausch100% (2)

- Solution Manual For Ethical Obligations and Decision Making in Accounting Text and Cases 4th EditionDocumento30 pagineSolution Manual For Ethical Obligations and Decision Making in Accounting Text and Cases 4th Editiongabrielthuym96j100% (18)

- 04 - Dfin404 - Insurance and Risk ManagementDocumento10 pagine04 - Dfin404 - Insurance and Risk ManagementHari KNessuna valutazione finora

- Ass#2 Values, Goals, PerformanceDocumento3 pagineAss#2 Values, Goals, PerformanceGian Kaye AglagadanNessuna valutazione finora

- Effect of Corporate Tax Aggressiveness On Firm Growth in Nigeria An Empirical AnalysisDocumento12 pagineEffect of Corporate Tax Aggressiveness On Firm Growth in Nigeria An Empirical AnalysisEditor IJTSRDNessuna valutazione finora

- Market Review: Task 1: Internal Memo Internal MemoDocumento11 pagineMarket Review: Task 1: Internal Memo Internal MemoMonu BhagatNessuna valutazione finora

- Brighter Smiles For The Masses - Colgate vs. P&GDocumento4 pagineBrighter Smiles For The Masses - Colgate vs. P&GkarthikawarrierNessuna valutazione finora

- Opm 2 AssginmentDocumento4 pagineOpm 2 AssginmentAmmar JuttNessuna valutazione finora

- Takele Abate 2405.14B.QA 01Documento9 pagineTakele Abate 2405.14B.QA 01ከጎንደር አይከልNessuna valutazione finora

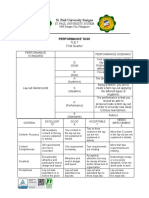

- St. Paul University Surigao: Performance TaskDocumento2 pagineSt. Paul University Surigao: Performance TaskRoss Armyr Geli100% (1)

- Civil Submittals StatusDocumento12 pagineCivil Submittals StatusCivil EngineerNessuna valutazione finora

- 1668685479145-Tender No 005 Supply of SmatrphonesDocumento31 pagine1668685479145-Tender No 005 Supply of SmatrphonesGeorge MbuthiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Entrepreneurship Education On Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Intention (Summary)Documento2 pagineImpact of Entrepreneurship Education On Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Intention (Summary)Sakshi RelanNessuna valutazione finora

- Donors TaxDocumento4 pagineDonors TaxRo-Anne LozadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Government of Maharashtra: Chief Minister'S Employment Generation Programme (Cmegp)Documento2 pagineGovernment of Maharashtra: Chief Minister'S Employment Generation Programme (Cmegp)Ravi Kiran RajbhureNessuna valutazione finora

- Fourosix-Reality Branding 1M SaniDocumento1 paginaFourosix-Reality Branding 1M SaniMahi AkhtarNessuna valutazione finora

- Stakeholder ProposalDocumento15 pagineStakeholder ProposalEYOB AHMEDNessuna valutazione finora

- Testing The Product Prototype: Asian Institute of Technology and EducationDocumento18 pagineTesting The Product Prototype: Asian Institute of Technology and EducationElixa HernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- Kingston Water Department Capital PlanDocumento11 pagineKingston Water Department Capital PlanDaily FreemanNessuna valutazione finora

- MPS FY2021-22:: CPD's Reaction OnDocumento49 pagineMPS FY2021-22:: CPD's Reaction OnAdnan AsifNessuna valutazione finora

- EDP101 EntrepreneurshipDocumento6 pagineEDP101 EntrepreneurshipLobzang DorjiNessuna valutazione finora

- Source Documents & Books of Original Entries (Chapter-3) & Preparing Basic Financial Statements (Chapter-5)Documento11 pagineSource Documents & Books of Original Entries (Chapter-3) & Preparing Basic Financial Statements (Chapter-5)Mainul HasanNessuna valutazione finora

- Exercise 1Documento4 pagineExercise 1Rekawt RashedNessuna valutazione finora

- Forest Guard Recruitment, 2021Documento3 pagineForest Guard Recruitment, 2021Abishek SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Strategic Financial ManagementDocumento8 pagineStrategic Financial Managementdivyakashyapbharat1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Deed of Absolute SaleDocumento2 pagineDeed of Absolute SaleKeziah HuelarNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 10 - Advanced VariancesDocumento19 pagineChapter 10 - Advanced VariancesVenugopal SreenivasanNessuna valutazione finora

- M05 Gitman50803X 14 MF C05Documento37 pagineM05 Gitman50803X 14 MF C05Levan TsipianiNessuna valutazione finora

- RPW Main Report and Annex q222Documento2 pagineRPW Main Report and Annex q222GalungNessuna valutazione finora

- Tax467, Tax 267 Practice QuestionsDocumento4 pagineTax467, Tax 267 Practice QuestionsRISNATUL UZMA HELMI RIZALNessuna valutazione finora

- Activity - 2 Entrep 1Documento2 pagineActivity - 2 Entrep 1Christina AbelaNessuna valutazione finora

- BMN 506 - Week 2Documento87 pagineBMN 506 - Week 2Shubham SrivastavaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rozita DaudDocumento92 pagineRozita DaudKwailim TangNessuna valutazione finora