Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Youth Design Participation To Support Ecological Literacy

Caricato da

María Teresa Muñoz QuezadaTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Youth Design Participation To Support Ecological Literacy

Caricato da

María Teresa Muñoz QuezadaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy: Reflections on Charrettes for an

Outdoor Learning Laboratory

Author(s): Nancy D. Rottle and Julie M. Johnson

Source: Children, Youth and Environments , Vol. 17, No. 2, Pushing the Boundaries:

Critical International Perspectives on Child and Youth

Participation - Focus on the United States and Canada, and Latin America (2007), pp. 484-

502

Published by: University of Cincinnati

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.17.2.0484

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

University of Cincinnati is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Children, Youth and Environments

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Children, Youth and Environments 17(2), 2007

Youth Design Participation to Support

Ecological Literacy:

Reflections on Charrettes for an

Outdoor Learning Laboratory

Nancy D. Rottle

Julie M. Johnson

Department of Landscape Architecture

University of Washington

Citation: Rottle, Nancy D. and Julie M. Johnson (2007). “Youth Design

Participation to Support Ecological Literacy: Reflections on Charrettes for an

Outdoor Learning Laboratory.” Children, Youth and Environments 17(2): 484-

502.

Abstract

Childhood experiences in nature have been found to hold myriad developmental

values, yet opportunities for such experiences have diminished greatly. If children

are to regain these values, firsthand experiences to learn from and care about and

for such natural places are essential. Such experiences, and the resulting

knowledge, caring and competence to act, serve as the foundation of what David

Orr defines as "ecological literacy." A meaningful context for such experiences and

literacy building is that of formal education, where youth may undertake hands-on

studies outdoors. These studies could occur in nearby open space, such as urban

parks, provided the parks were appropriately designed. This paper describes

youths’ participation in design charrettes for a park’s “outdoor learning laboratory,”

reflects on the process and outcomes, and suggests potentials to support ecological

literacy through both the charrette process and the designed learning environment.

Keywords: youth design participation, charrettes, ecological literacy,

environmental learning, urban parks

© 2007 Children, Youth and Environments

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy... 485

Introduction

Fifty years ago, Rachel Carson ruminated on the value of childhood exploration of

the natural world in her book, The Sense of Wonder. Among her reflections, she

stated: “Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength

that will endure as long as life lasts….There is something infinitely healing in the

repeated refrains of nature” (1956, 88-89). These ideas have been affirmed by the

extensive research of Stephen and Rachel Kaplan on people’s responses to nature

(1989). Richard Louv has explored the importance of nature in children’s lives in

Childhood’s Future (1990) and Last Child in the Woods (2005). In this most recent

book, he recounts studies indicating that ADHD-diagnosed children who have

experiences with green spaces show increased attention. Yale professor Stephen

Kellert emphasizes the benefits of contact with nature for the cognitive, affective,

and moral development of children and youth. He concludes that contact with

nature produces the “greatest maturational benefits when it occurs in stable,

accessible, and culturally relevant social and physical environments” (2005, 88).

Yet for all the acknowledged benefits, experiences in nature are rapidly

disappearing from children’s and youths’ daily lives in the United States. Increasing

urbanization and societal changes have altered where and how children and youth

spend their time. Robert Michael Pyle is concerned that the loss of personal

intimacy with the living world amounts to an “extinction of experience” and a

subsequent lack of relationship with nature. Without such personal contact, we not

only miss nature’s innate therapeutic benefits but also awareness, appreciation and

the will to preserve local habitat. “What is the extinction of the condor to a child

who has never known a wren?” (1993, 145-47).

Like Pyle, David Orr identifies childhood as a critical time to inspire what he

describes as “ecological literacy,” stating that it “is driven by the sense of wonder,

the sheer delight in being alive in a beautiful, mysterious, bountiful world” (1992,

86). Orr describes the basis of ecological literacy as having three components: “the

knowledge necessary to comprehend interrelatedness, … an attitude of care or

stewardship,…[and] the practical competence required to act on the basis of

knowledge and feeling” (1992, 92). He underscores the importance of such literacy

for building a more sustainable future; however, the means with which to develop

ecological literacy is threatened. He asserts: “Ecological literacy is becoming more

difficult, I believe, not because there are fewer books about nature, but because

there is less opportunity for the direct experience of it….A sense of place requires

more direct contact with the natural aspects of a place, with soil, landscape, and

wildlife” (1992, 88-89). Orr notes the importance of experiences in nature being

informed by a teacher or mentor. The value of an adult mentor or teacher is

validated by Louise Chawla’s research on environmentalists’ significant childhood

experiences (1999).

Clearly, nature experiences are needed in childhood both for their therapeutic

values and as a keystone of ecological learning that builds ecological literacy.

Accessible natural places, time in these places, and people who can mentor in such

places are needed to make these experiences most beneficial. In the context of

children’s lives today, schools hold tremendous potential to provide such positive

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy... 486

experiences. The school site and/or nearby parks and open space can effectively

serve as the context, especially when they are designed to optimally support place-

based learning and linked with school curricula.

Yet, urban parks designed for environmental learning are uncommon, and a paucity

of literature exists to guide their development. We set out to address this void,

using several methods of study. Recognizing a possible opportunity for authentic

youth participation—the need for which has been well documented by Roger Hart

(1997) and others—we engaged youth from a targeted user group in a participatory

design activity for a local park slated for redesign. We suspected that involvement

from youth in designing an environmental learning park would serve not only to

inform designers, but would also promote in young people the knowledge, caring

and competency that are the hallmarks of ecological literacy. This paper tells the

story of the design charrettes (workshops) we conducted with two sixth-grade

science classes, reflects on that process, outlines what we learned about designing

environmental learning parks, and suggests a role that participatory design

processes may play in developing ecological literacy.

Program Description and Research Team Goals

In Seattle, a group of approximately 250 inner-city sixth graders recently

participated in a pilot science program at the city’s Magnuson Park, using its

meadows, forest and beach as an outdoor learning laboratory. A portion of this

350-acre multipurpose park, a former naval air station, soon will be transformed

from a disturbed habitat mosaic to a 65-acre diverse wetland complex. The Seattle

School District, Seattle Parks and Recreation Department, and Earthcorps, a non-

profit group specializing in ecological restoration and education, established the

Magnuson Outdoor Learning Laboratory (MOLL) pilot program to test the park’s

viability as a venue for implementing part of the school district’s middle school

science curriculum.

Program goals had been developed through a study of the district’s educational

needs, in response to the opportunities afforded by the park as it now exists and

anticipating the construction of new habitats in its redesign. In addition, educators

felt the park offered interdisciplinary learning opportunities, and pilot program

directors consequently incorporated a service-learning component into the pilot

program. Goals of the science and service-learning curriculum were that the

students:

• learn field-science skills such as measuring, comparing, setting up a research

question, and mapping;

• become familiar with aspects of habitat restoration (e.g., native and invasive

plants, positive and negative influences on habitat, relationship of animals

and habitat, restoration practices and resulting habitat quality); and

• learn to use landscape restoration hand tools effectively.

The pilot program involved classes from two Seattle schools with high percentages

of minority and low-income students. Each class spent three field days at the park,

spread across each season of the school year. Teachers and Earthcorps interns led

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy... 487

small groups in science investigations and in landscape restoration activities, with

half of the site time spent on each. Activities were located in a portion of the park

that contains diverse recovering, restored, and weedy habitats (meadow, forest,

drainage ditch, lake shoreline), parking areas that were used for program staging,

and a grassy hill that overlooks the park and adjacent lake. Students investigated

and documented life in the soil, compared wildlife counts in different habitats,

conducted simple experiments of their own design, removed invasive plants, and

planted new native trees (Figure 1). Weather was highly variable, with several days

of rain and cold. Warm-up games incorporating ecological concepts became an

appreciated component of the curriculum.

Figure 1. Students participating in the Magnuson Outdoor Learning

Laboratory (MOLL) Pilot Program counting insects in their

study plot (photo: Nancy Rottle)

After serving on the steering committee that informed the planning of MOLL, the

authors of this paper identified research opportunities related to this pilot program.

Our research had two primary goals: first, to provide insights for the redesign of

the park’s habitat components, so that these areas might optimally function as an

outdoor learning laboratory to support ecological learning; and second, to begin

articulating general design principles for environmental learning parks that support

the development of children’s and youths’ ecological learning and literacy. We

undertook a literature review of precedents and theory to inform this context. Site-

based research methods included observation of students on their field

investigation days and interviews with field leaders and teachers. Following the

three days of the on-site program, we conducted design charrettes with two classes

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy... 488

of students from one of the schools. The design charrettes were intended to solicit

the students' ideas on how to make the park best support ecological learning. Since

youth were not directly involved in the design process, we believed this aspect of

the research would provide a unique and valuable set of insights for park staff and

the park designers, drawn directly from the students’ experiences at Magnuson

Park. We also anticipated that the charrettes would reinforce and extend students'

learning, and while the research was not designed to test this hypothesis, the

participatory experience yielded educational insights that we discuss below.

Youth Design Charrettes and Results

One of the participating teachers welcomed the opportunity for students to engage

in a series of design charrettes as part of their classtime activities. Design

charrettes were undertaken as three sessions: 1) posters of ideas for elements

needed in the park; 2) model designs of places for ecological learning, showing

spatial relationships among elements and selected habitats; and 3) postcard

reflections on significant elements, places, experiences, and/or learning

opportunities based on the previous charrette sessions and on the youths’ field

experiences. Charrettes were conducted in the students’ classroom with two

classes that were separated by gender: one class of 30 boys and one class of 23

girls. The first two sessions were undertaken in one-hour timeframes. During the

first two charrettes, small groups were created and a University of Washington

student and/or faculty member facilitated each group. 1 The third charrette activity

was administered by the teacher as a brief in-class exercise.

Session 1: Posters of Ideas for Elements Needed in the Park

The first design charrette session involved individual and small group brainstorming

activities to generate diverse ideas for improving the park. After asking students to

reflect on their field study experiences in the park, they were posed with the central

question: If you had $1,000,000, what would you do with it to make Magnuson

Park a better learning park? We used the “conceptual content cognitive map”—

3CM—method (Kearney and Kaplan 1997; Micic 2001), a process that asks subjects

to write their topical opinions or ideas onto sticky notes, and then arrange the notes

to form groupings as a “conceptual cognitive map.” We applied this method to draw

out the students’ design ideas, asking them to write down each of their proposals

for the park on a sticky note. Once the individuals had created their own sets of

ideas, we had them join with their small groups and arrange the notes in categories

on a large “ideas poster” (Figure 2). The transfer of all notes onto this sheet

became challenging, so with the second class, we asked students to select only

their best ideas to transfer and arrange onto the poster.

1With support from a scholarship (see Acknowledgements), Bachelor of Landscape

Architecture student Jennifer Low played a key role in this research project, including the

charrette introductions and activities.

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy... 489

Figure 2. On the first day of the charrettes, students worked in small

groups to generate ideas for making a better learning park.

Students wrote the ideas on sticky notes, and then categorized

and illustrated their proposals on an informal poster (photo:

Nancy Rottle)

Then students were asked what these ideas might look like. Small photographs of

particular design elements (e.g., a footbridge) were provided as additional “idea

cards” for students to use as they desired, and they were encouraged to draw

pictures on blank cards to illustrate their mental images. Finally, each student was

asked to help prioritize which three of their group's ideas seemed most important

by putting sticker dots next to those three. Each group shared their favorite items

with the rest of the class.

The students quickly grasped the idea that environments could be created that

afforded better habitat for animals as well as for their studies; these included both

habitat restoration (e.g., “less invasive plants,” trees, fish and frog ponds, and

wetlands) and “houses” for animals. The students also gave numerous ideas for

how to make it easier and more comfortable for them to engage in outdoor

learning: benches and bathrooms topped the list, with several groups noting the

need for picnic tables, shelter, and food. More unique suggestions included an

observation tower, treehouse, bird blind, platforms, and bridges to observe wildlife;

cameras and more “quadrats” 2 for study; and “wood to build bird houses, bee hives

2

Students had used 1-meter square "quadrat" frames to define an area for their field

investigations

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy... 490

and ant farms.” Several groups proposed a science lab and indoor science learning

facilities. The most frequently stated ideas fell into the categories shown on Table

1.

Table 1. Content summary of ideas for elements to include in

environmental learning parks generated in Session 1

• Animal houses

such as birdhouses, butterfly center, snake house

• Animal habitats

including pond, native plants, trees, river

• Animals

notably birds, bugs, bats, and small animals

• Plants and greenhouse

• Water and water features

• Habitat observation places

such as treehouse, platforms

• Park amenities and comforts

such as benches, bathrooms, shelter, picnic tables, food

• Features related to cleanliness

including clean water and pooper-scooper dispenser

• Recreational facilities

such as football, basketball, baseball, walking and bike trails, maze

• Ways for moving

such as dirt biking, canoes

• Classroom facilities

• Tools and supplies

• Expansion, such as more park and camping facilities

Session 2: Models of Designed Places for Ecological Learning

In the second session we re-introduced student groups to the idea posters they

created in the first charrette, and asked each group to consider the types of habitat

they would like in the park. To stimulate their thinking, we provided a handout that

listed a variety of habitat types (see Figure 3). A large cardboard base was

provided to each group, and we asked students to draw where these habitats and

the proposals from their posters might be located in their park. Students were

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy... 491

given, and brought some of their own, model making materials to create their

preferred habitat types and program elements. They worked together to represent

elements from their posters that would be placed within the habitats, paths that

would connect the habitat areas, and other ideas that emerged through the creative

process (Figures 4-7).

Figure 3. Handout given to students to guide their model-making process

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy... 492

Figures 4-6. The model-making activity was divided into four steps: a)

deciding upon the habitats they would include in their

learning park; b) drawing habitats and built elements on the

cardboard base c) constructing their park elements and d)

presenting their model to the class. Students also consulted

their idea posters from Session 1 to stimulate model-making

ideas (Photos: Nancy Rottle and Jennifer Low)

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy... 493

Figure 7. Example of a finished charrette model completed by a small

group of sixth-graders (photo: Jennifer Low)

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy... 494

The students’ ten models presented ideas for an array of habitats. All contained a

water body or wetland. The most common habitat areas that students elected to

create were cover types of forest and grass area, and topographic features of hills

and flat land. The models contained a wide range of different program elements to

support environmental learning. Consistent with the idea generation exercise in

Session 1, bathrooms and benches were most common, bridges were second, and

greenhouses and basketball courts third. The ideas broke out into categories of

park amenities, habitat observation, recreational facilities, and built indoor facilities.

Frequencies of the ideas represented on the models are shown on Table 2.

Table 2. Frequency of Ideas Represented on Models, Session 2

HABITAT

Water body or wetland

Pond 7 River* 2

Lake 3 Shoreline 2

Wetland 3 Creek* 1

Cover types and topography

Forest, Trees 6 Hill 7

Grass Field 5 Flat Land 4

New Restored Area 3 Depressions 1

Parking Lot 3 Island* 1

Blackberry Field 2

Meadow 2

Bird Habitat* 2

Plant Area* 1

Flowers* 1

* These habitat types were not included on the charrette

handout.

PROGRAM ELEMENTS

Park amenities

Bathrooms 6 Light 1

Benches 6 Water Fountains 1

Picnic Area/Tables 2 Garbage Receptacles 1

Trolley Cart 1 Janitor 1

Habitat and observation

Bridge 4 Bird Food 1

Platform/Boardwalk 2 Birdhouse 1

Tower 1 Bug Eating Space 1

Treehouse 1

Recreational facilities

Basketball Court 3 Swings/Playground 1

Dog Park 2 Place to Swim 1

Bike Trails 1 Water Park 1

Bike Rack 1 Boat Launch 1

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy... 495

Indoor facilities

Green House 3 Snake House 1

Community Center/ 2 Butterfly House 1

Teen Center

Restaurant 1 Bed + Breakfast 1

Library 1 Water Fountains 1

Science Lab 1

Session 3: Postcard Reflections on Significant Ideas and Experiences for

Ecological Learning

Two weeks after we completed the second charrette, we asked the students to

undertake a brief reflective activity that was administered by their teacher. The

students wrote 8.5 x 11-inch “postcards” to the research team, answering two sets

of questions: “The most important idea from our charrettes was…” and “what we’d

study there…” was written on one side of the postcard as a prompt for words and/or

drawings. On the other side of the postcard was: “The best place for learning at

Magnuson Park was…” The students’ responses yielded insights about what they felt

was most important for their environmental learning at the park, and the benefits

of the charrette process.

The majority of students’ responses regarding the charrettes fell into three

categories:

Structures for Study

Almost half of the students wrote about structures that made studying possible or

better (such as a bird blind, bridge over a pond, butterfly house). These students

were sometimes specific about a type of organism they would study (e.g., birds,

butterflies) and sometimes very general (e.g., nature, the environment).

Greenhouses and science centers were popular ideas: five boys thought that a

greenhouse was the best idea, “to keep living insects and plants in there,” and six

students—mostly girls—liked the idea of a science center where they could “study

about the bugs and plants they have encountered at the park.”

Habitat

A third of the students, mostly boys, said that the most important idea was about

some type of habitat, and their subjects of study centered on the relationship

between animals and plants or between animals and habitat: “The important idea

was the forest because it’s a great habitat for lots of animals…we would study what

different animals live there and how they would live there,” and “My most important

idea is a frog pond and a fish pond…we would study the temperature of the two and

the frogs and the fish.”

Charrette Process

Several students—almost all girls—wrote about the charrette process (e.g.,

“mapping our ideas and putting them together”; “putting the stickies on the paper”)

and identified what they would learn through the process (e.g., “science, math, art,

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy... 496

measuring”; “to use all ideas that come to you”). One student wrote that the most

important part was

working together and each of us doing our part and coming up with ponds and

other things that make a good habitat….We would study an area that we

planned to turn from a bad habitat to a good habitat to see if it could be done

and to make the park a better place.

In contrast to the previous session outcomes, only a few students mentioned

general amenities for park users in this reflective activity. These included lunch

tables and bathrooms, a dock, and basketball courts for fun and “to study a jump

shot.” One person advised, “Use the bathroom idea because Magnuson Park does

not have a lot.”

Interestingly, students’ reflections about the best place for learning at Magnuson

Park—based on their field experiences there—didn’t correlate highly with their

favorite charrette ideas. Popular “best learning places” were the blackberry bush

areas that students cleared and mulched and the planting areas where the service

learning projects occurred, yet these areas needing repair weren’t often in the

models or cited as students’ favorite charrette ideas. These results may indicate

that the design process is not conducive to suggesting “messy” or degraded

environments where active service learning can occur, yet students valued these

types of places for their learning.

Our Own Learning

At the outset, we initiated the charrettes to get the students’ perspectives and

ideas about how to support environmental learning for Magnuson Park and other

park settings. We also felt that the charrette process would reinforce their on-site

learning, and contribute to the development of the students’ ecological literacy.

Our own learning from the charrette process fell into three categories that will each

be discussed in the following sections. First, what is the best way to conduct a

design process with only a limited amount of time in the classroom, and what were

the kinds of outcomes that each component of the charrette could yield? Second,

what could the students’ responses tell us about how to design environmental

learning parks, in general and potentially applied to Magnuson Park? Third, did the

charrettes have any side benefits of extending or reinforcing the students’ learning,

or otherwise contribute to their ecological literacy? How did the charrette process

relate to the students’ overall experience of the Magnuson Outdoor Learning

Laboratory pilot program? What could they tell us about the places or types of

activities in the pilot program that made the most impression on the students?

1. The Charrette Process

The charrette process and the outcomes it yielded mimicked a typical design

process. The Idea session (Session 1), using the adapted conceptual content

cognitive map (3CM) process, generated the widest range of ideas. The 3CM

process was an effective way for students to rapidly generate program elements, to

share them, and to look for commonalities. Some ideas were fitting for an

environmental learning park, while others (such as “motor scooter racing” and a

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy... 497

“food court”) went further afield. Our adapted instructions asking the second cohort

(the female group) to pick out their best ideas to add to their group’s list may

account for the fact that these lists were more related to environmental learning, or

park care, than those from the first cohort (the male group).

The Model session (Session 2) showed fewer and more practical ideas, and may

have been limited by what the students felt they could construct on their group

models. However, the models showed topographical forms, which were absent from

the idea lists, and were more explicit about habitats (which may have been a result

of defining habitats as the first model-building step). The models also began to

demonstrate spatial relationships between facilities and the environment, for

instance, a bridge over a pond, a tower and treehouse.

The Postcard reflection session (Session 3) yielded the highest percentage of

learning-focused park ideas, since this was a filtering exercise that asked about

their “most important idea” and what it would enable them to study. The

disadvantage of this exercise was that, with two weeks between the activity and the

reflection (and their lists and models absent from the classroom), the students may

have been more inclined to remember the big, figurative, and/or novel ideas, such

as the greenhouse and science center. Nonetheless, the postcards were useful for

giving insight into students’ perception of the charrette process and what they may

have gained from it.

We found that for the Idea and Model sessions, it was effective to have small

groups of four to six students with adults facilitating the process. It was also

valuable to have a very clear introduction and instructions to set behavior

expectations for the new activity. We found that breaking up the session into short

segments, typically 20 minutes maximum, held the students’ attention and

circumvented off-track activity, although we did feel that the model making session

could have gone longer than one hour. The teacher noted that showing students an

example landscape model was helpful, and that we might have showed others as

well to give the students more familiarity with the design process and products.

We also recognized the critical importance of the students’ prior experience with the

park for providing concrete memories on which to conceptualize and build, and for

developing an appreciation for the objectives of an environmental learning park.

The teacher suggested that we might have held the charrette between the second

and third visits, rather than at the end of the year, so the students could revisit

Magnuson Park and envision how their ideas could be applied to the site.

We did not address practicality or give parameters related to real construction

possibilities, and consequently students proposed ideas such as a full-blown science

center that are not feasible within the budget parameters for the redesign of

Magnuson Park. In retrospect, and given more time, we might have added another

filter and asked the students to prioritize program elements within a more

restricted budget so that their ideas had greater potential of integration with the

park’s final design.

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy... 498

2. Designing Environmental Learning Parks

The charrette sequence was intended to evoke the students’ perceptions on how

the environment could better support their science learning, and it helped us to

understand several perspectives:

• These students, as anyone would, brought their expectations of what

happens at parks and school to their outdoor learning experience. They

wanted to have typical park conveniences (especially real bathrooms and

food), recreational facilities, cleanliness, and amenities such as benches and

picnic tables; several students suggested typical classroom facilities such as

a science laboratory and science center. These responses underscore the

need for previous experience with the outdoors, and with outdoor learning, to

inform this new prototype. It also told us that basic amenities such as

regular bathrooms and benches were important to a positive learning

experience and may help students to feel more comfortable in

“environmental learning park” areas. Similarly, the popularity of science

centers and greenhouses might indicate the need for a warm place to study

on cold, rainy days.

• Most models contained some kind of space conducive to play—a grassy field,

kite hill, dog park, and/or basketball court. We might interpret this to say

that play is still an important part of a field trip, even for middle schoolers,

and that even a small space for warming up and taking a break from

immersion in habitat and science study would make the experience more

positively memorable.

• Changes in topography, views and structures that alter perspective may add

contrast, drama and adventure, thereby yielding positive and memorable

experiences for youth.

• Spaces with cohesion and identity help to develop conceptual clarity.

Students were able to designate distinct areas as certain types of habitat,

and then relate animal life to those habitats in the models and reflective

postcards. At this stage, most students require tangible examples; while

they are able to apply relational concepts (such as an animal to its habitat),

they may have more difficulty with concepts such as "flows" between spaces

with subtle differences. This idea correlates highly with reports from the

outdoor leaders that more distinct boundaries are needed for teaching as well

as for behavior management.

• While design charrettes can be informative, they provide only part of the

lessons that students can offer park designers. As noted above, when we

asked the students to describe the best place for learning at Magnuson Park,

one of the most common responses was “the blackberry bushes,” which is

where most of the active restoration activities took place. Students linked

their science learning to the restoration activity; this active endeavor was

memorable, repeated, and may have helped students to feel they were

making a difference. Recognizing the inherent learning in the habitat

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy... 499

restoration process, design of certain areas might take a long-term process-

approach, with proactive plans to engage students in restoration as part of

their science as well as service curriculum.

3. Charrette Benefits to the Students: Fostering Ecoliteracy

While our study was not designed to test the students’ learning, there is some

evidence that the charrette process may have combined with their field experiences

to contribute to their developing ecoliteracy. Orr defines the foundation of

ecological literacy as having three components: caring about the environment,

enough knowledge to comprehend interrelatedness within the environment, and

practical competence to enable a person to act on the basis of this feeling and

knowledge (1992, 92). Therefore, we use these criteria of caring, knowing and

competence to examine whether the charrettes may have helped to foster

ecoliteracy.

Caring

Numerous postcard responses regarding what students felt was important in their

charrette ideas referred to helping animals or their habitat, demonstrating the

empathy required for ecoliteracy (Orr 1992). In addition, the students seemed to

enjoy the charrette experience, and responses on the postcards were generally

positive. One response to the “most important idea” question was “that it was nice

that we all have a nice time doing it with you,” and on another “It was fun and

learning-ful.” Having such positive experiences to support outdoor learning may

enhance caring about the environment.

Knowing

The numerous references to habitat in the reflective postcards suggest that the

model-building may have reinforced the cognitive lessons from the site visits. The

conceptual connection between habitat and animals is an example of

interrelatedness and an essential foundation in environmental education. Promoting

this type of understanding through the act of collaborative design may therefore

contribute to building of youths' knowledge.

Competence

The experience may have helped the students to feel more competent in creating or

restoring habitat, evidenced by end-of-the-year evaluations that the MOLL program

administered to the two participating schools. On a question that asked the

students to describe the steps needed to turn a parking lot into a small natural

area, the students from the school that participated in the charrettes did

significantly better than those with only the field experience, and they improved

substantially from the pre-test. Whereas in the pretest less than 25 percent of the

students even tried to answer this question, 90 percent made an attempt for the

post-test. A third described this process sufficiently for evaluators to rate the

degree of process description as “somewhat” or “well.” For example, one student

wrote: “First, get a plan. Next hire the people. Then get started. Block off the

people from getting into the parking lot. Take off the part of the lot you are getting

rid of. Put soil down. Grow Plants. Put benches or chair and you are set.” In

contrast, only 7 percent from the “control” school that participated only in the field

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy... 500

experience could describe the process, and only 60 percent of this group made an

effort to do so. Engaging students in the design of their environment may help to

awaken students' awareness of and confidence in their own abilities. This notion is

supported by some of the responses on the reflective postcards, such as “The most

important idea I learn [sic] is that I know the model I made will be something I like

at the park.”

Reflections and Questions

Charrettes may support ecological literacy through both the outcomes that inform a

designed place and the learning that occurs in the participatory process. We

engaged young people in the design charrette process with the belief that design

should be informed by asking them about their needs, desires and ideas. Our

philosophy was confirmed through this participatory process; youths’ answers may

surprise adults as well as validate adult perceptions. Engaging youth in design

participation may reveal pragmatic, useful elements that are missing in a built

environment and inspire fresh, creative ideas.

Unfortunately, involving students is not typically part of a consultant’s scope of

work for designing parks or other places for youth; without a sanctioned

involvement in the design process, it is unlikely that youths’ ideas will be sought or

incorporated. We initiated and were able to conduct these charrettes as scholars

and only with the aid of an academic scholarship and student volunteers. While we

have given the results to the park designers, it remains to be seen whether the

students’ ideas will be incorporated into the design for Magnuson Park. The complex

process of creating a wetland park involves high-level technical application, a

convoluted regulatory process and budgetary restrictions, often resulting in even

the professional designers’ ideas being diluted. However, if public clients require

that youth be meaningfully involved in the design process, their ideas can inform

designers and have a better chance of being brought to reality.

Additionally, involvement in the process of participatory design may have

immediate benefits to students, prior to or without the end result of a built place.

In particular, on-site learning and involvement in design charrettes may reinforce

each other, coalescing to create powerful developmental experiences. Such

reciprocal experiences may thereby further the knowledge, caring and

competencies required to cultivate ecologically literate citizens. Moreover, such

involvement affords opportunities for mutual learning, teaching youth as well as

designers.

To make youth participation in design of environmental learning places more

widespread and effective, the potential benefits for both design and learning need

to be documented. Studies are needed to understand how youths’ engagement in

design processes may enhance cognition, affect or skill, and methods for involving

youth in design processes need to be further evaluated. While we found the

charrette process to be an effective method to draw out youths’ ideas, it would be

valuable to explore more robust and extended youth participation processes to both

influence projects and enrich students’ ecological literacy. What processes best

promote learning for both designers and students? Does engagement in design-

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy... 501

based processes further higher-order learning, enhance retention, positively

influence attitudes toward the environment, or promote a sense of empowerment?

With young people’s voices at the table, more opportunities for useful, safe,

comfortable and inspiring experiences with nature may occur, affording this

population the connection with nature that scholars have identified as important to

their cognitive, affective, and moral development. And, if some of the sixth-graders’

insights are incorporated at Magnuson Park, they may get to experience the built

outcomes of their own insights.

Acknowledgements

The research team included University of Washington Landscape Architecture faculty Nancy

Rottle and Julie Johnson, and Landscape Architecture students Jennifer Low, Clayton

Beaudoin, and Garrett Devier. A group of students from Landscape Architecture and from

the Community, Environment and Planning Program generously helped facilitate small

groups for the youth design charrettes. We are particularly grateful for the support of the

Mary Gates Research Training Grant that Jennifer Low received and enabled her to play a

key role in the research.

Nancy Rottle is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Landscape

Architecture at the University of Washington, a former elementary school teacher

and a licensed landscape architect with 15 years of professional experience. Her

scholarship focuses on planning and design for landscapes that provide connections

to and educational opportunities within natural and cultural environments, and the

pedagogy of community design engagement.

Julie M. Johnson is an Associate Professor in the Department of Landscape

Architecture at the University of Washington. She is a licensed landscape architect

and certified planner whose research and teaching has focused on civic landscape

design and participatory processes, notably in the context of children’s outdoor

learning environments. She has authored an ASLA LATIS monograph on design of

school landscapes for children’s learning.

References

Carson, Rachel (1956). The Sense of Wonder. New York: Harper & Row.

Chawla, Louise (1999). “Life Paths into Effective Environmental Action.” The

Journal of Environmental Education 31(1): 15-26.

Hart, Roger A. (1997). Children’s Participation: The Theory and Practice of

Involving Young Citizens in Community Development and Environmental Care. New

York: UNICEF.

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Youth Design Participation to Support Ecological Literacy... 502

Kaplan, Rachel and Stephen Kaplan (1989). The Experience of Nature: A

Psychological Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kearney, Anne R. and Stephen Kaplan (1997). “Toward a Methodology for the

Measurement of Knowledge Structures of Ordinary People: The Conceptual Content

Cognitive Map (3CM).” Environment and Behavior 29(5): 579-617.

Kellert, Stephen (2005). Building for Life: Designing and Understanding the

Human-Nature Connection. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Louv, Richard (1990). Childhood’s Future. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

----- (2005). The Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit

Disorder. Chapel Hill, N.C.: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

Micic, Shawna Marie (2001). Testing New Methods for Improving the

Effectiveness of Collaborative and Participatory Design and Planning Processes:

Conceptual Content Cognitive Map (3CM). Master of Landscape Architecture Thesis,

University of Washington.

Orr, David W. (1992). Ecological Literacy: Education and the Transition to a

Postmodern World. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Pyle, Robert Michael (1993). The Thunder Tree: Lessons from an Urban

Wildland. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

This content downloaded from

130.195.21.27 on Wed, 30 Jan 2019 15:13:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Muscular System Manual - E-Book: The Skeletal Muscles of The Human Body - Joseph E. MuscolinoDocumento5 pagineThe Muscular System Manual - E-Book: The Skeletal Muscles of The Human Body - Joseph E. MuscolinonamurameNessuna valutazione finora

- Urban Wild Things: A Cosmopolitical Experiment: S.j.hinchliffe@open - Ac.ukDocumento16 pagineUrban Wild Things: A Cosmopolitical Experiment: S.j.hinchliffe@open - Ac.ukMaría Teresa Muñoz Quezada100% (1)

- Urban Wild Things: A Cosmopolitical Experiment: S.j.hinchliffe@open - Ac.ukDocumento16 pagineUrban Wild Things: A Cosmopolitical Experiment: S.j.hinchliffe@open - Ac.ukMaría Teresa Muñoz Quezada100% (1)

- MTE531 SyllabusDocumento11 pagineMTE531 SyllabusJoe Wagner100% (1)

- Beck BDIDocumento7 pagineBeck BDIgabopeluditoNessuna valutazione finora

- Ecological Literacy and Socio Demographics Who Are The Most Eco Literate in Our Community and WhyDocumento15 pagineEcological Literacy and Socio Demographics Who Are The Most Eco Literate in Our Community and WhyMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Artful Climate Change Communication: Overcoming Abstractions, Insensibilities, and DistancesDocumento12 pagineArtful Climate Change Communication: Overcoming Abstractions, Insensibilities, and DistancesMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Co-Becoming Bawaka - Towards A Relational Understanding of Place-SpaceDocumento21 pagineCo-Becoming Bawaka - Towards A Relational Understanding of Place-SpaceMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Engaging Students To Learn Through The Affective DomainDocumento14 pagineEngaging Students To Learn Through The Affective DomainMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Medema 2020 COVID Correlation SewageDocumento22 pagineMedema 2020 COVID Correlation SewageMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Opportunities For Urban Ecology in Community and Regional PlanningDocumento2 pagineOpportunities For Urban Ecology in Community and Regional PlanningMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Imagining Climate ChangeDocumento14 pagineImagining Climate ChangeMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Individualising The Future PDFDocumento15 pagineIndividualising The Future PDFMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rethinking Organization Theory - The Fold, The Rhizome and The Seam Between Organization and The Literary PDFDocumento19 pagineRethinking Organization Theory - The Fold, The Rhizome and The Seam Between Organization and The Literary PDFMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Imagining Climate ChangeDocumento14 pagineImagining Climate ChangeMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Individualising The Future PDFDocumento15 pagineIndividualising The Future PDFMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Effect of Environmental Education On The Ecological Literacy of First-Year College StudentsDocumento8 pagineThe Effect of Environmental Education On The Ecological Literacy of First-Year College StudentsMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Whole Systems Thinking As A Basis For Paradigm Change in EducationDocumento477 pagineWhole Systems Thinking As A Basis For Paradigm Change in EducationMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Capital and Community GovernanceDocumento18 pagineSocial Capital and Community GovernanceMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Creative Geographic Methods - Knowing, Representing, Intervening. On Composing Place and PageDocumento23 pagineCreative Geographic Methods - Knowing, Representing, Intervening. On Composing Place and PageMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Affect and The Dialectics of UncertaintyDocumento19 pagineAffect and The Dialectics of UncertaintyMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Imagining Climate ChangeDocumento14 pagineImagining Climate ChangeMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Capital and Community GovernanceDocumento18 pagineSocial Capital and Community GovernanceMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Attitudes Towards Potential Animal Flagship Species in Nature Conservation PDFDocumento13 pagineAttitudes Towards Potential Animal Flagship Species in Nature Conservation PDFMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Biodiversity Conservation and The Extinction of ExperienceDocumento5 pagineBiodiversity Conservation and The Extinction of ExperienceMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Scholars Research Library: Seyed Jamal F. HosseiniDocumento6 pagineScholars Research Library: Seyed Jamal F. HosseiniMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nihms657069 - Op Puerto RicoDocumento21 pagineNihms657069 - Op Puerto RicoMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Heyer Et Al - 2017Documento19 pagineHeyer Et Al - 2017María Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 s2.0 S0161813X13001514 Main PDFDocumento11 pagine1 s2.0 S0161813X13001514 Main PDFMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNessuna valutazione finora

- JSSATEB - Calendar - of - Events - 2023 - 24 - Even - Semester - IV SemDocumento2 pagineJSSATEB - Calendar - of - Events - 2023 - 24 - Even - Semester - IV SemJNessuna valutazione finora

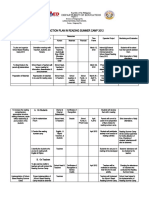

- An Action Plan in Reading Summer Camp 2012: Department of EducationDocumento3 pagineAn Action Plan in Reading Summer Camp 2012: Department of EducationJESSICA MOSCARDON100% (1)

- Nigerian Defence Academy Academic BranchDocumento9 pagineNigerian Defence Academy Academic BranchGiwa MuqsitNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Write The Dartmouth College Supplemental Essays - Command EducationDocumento6 pagineHow To Write The Dartmouth College Supplemental Essays - Command EducationSamNessuna valutazione finora

- COT RPMS Inter Observer Agreement Form For T I III For SY 2023 2024Documento1 paginaCOT RPMS Inter Observer Agreement Form For T I III For SY 2023 2024alice mapanaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Aqa A Level English Language B Coursework Grade BoundariesDocumento4 pagineAqa A Level English Language B Coursework Grade Boundariesegdxrzadf100% (1)

- ACR Convergence MeetingDocumento2 pagineACR Convergence MeetingGHi YHanNessuna valutazione finora

- DEC 13 DIfferences of Natural HumanitiesDocumento3 pagineDEC 13 DIfferences of Natural HumanitiesTessie GonzalesNessuna valutazione finora

- Communication Skills For Medicine PDFDocumento2 pagineCommunication Skills For Medicine PDFCarmen0% (3)

- HPGD3203 Emerging Tech in Teaching Learning - Esept21 (CS)Documento197 pagineHPGD3203 Emerging Tech in Teaching Learning - Esept21 (CS)azie azahariNessuna valutazione finora

- 001 How To Use The Speak English Now PodcastDocumento4 pagine001 How To Use The Speak English Now PodcastCamilo CedielNessuna valutazione finora

- University of The Philippines Diliman: Check With Respective CollegesDocumento1 paginaUniversity of The Philippines Diliman: Check With Respective CollegesMeowthemathicianNessuna valutazione finora

- Parent'S Involvement in School LearningDocumento2 pagineParent'S Involvement in School LearningVen Gelist TanoNessuna valutazione finora

- LCFDocumento5 pagineLCFVashish RamrechaNessuna valutazione finora

- Creative Writing Rubric - Photo Story 3Documento4 pagineCreative Writing Rubric - Photo Story 3Sherwin MacalintalNessuna valutazione finora

- CELPIP Path and Checklist October 2020Documento2 pagineCELPIP Path and Checklist October 2020MYNessuna valutazione finora

- DM No. 176 S. 2020 Alignment To Child Protection Policy To The New Normal Et. AlDocumento6 pagineDM No. 176 S. 2020 Alignment To Child Protection Policy To The New Normal Et. AlAnj De GuzmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Lamu BrochureDocumento2 pagineLamu Brochureluyando211Nessuna valutazione finora

- Penelusuran Minat-Bakat Untuk Siswa Sma Di Yogyakarta: Rostiana, Kiky Dwi Hapsari SaraswatiDocumento6 paginePenelusuran Minat-Bakat Untuk Siswa Sma Di Yogyakarta: Rostiana, Kiky Dwi Hapsari SaraswatiSay BooNessuna valutazione finora

- THE EFFECTS OF HAVING AN OFW PARENT ON THE ACADEMI Group 5Documento3 pagineTHE EFFECTS OF HAVING AN OFW PARENT ON THE ACADEMI Group 5acelukeNessuna valutazione finora

- Implementing Audio Lingual MethodsDocumento8 pagineImplementing Audio Lingual MethodsSayyidah BalqiesNessuna valutazione finora

- National Knowledge Commision and Its Implication in Higher EducationDocumento73 pagineNational Knowledge Commision and Its Implication in Higher Educationabhi301280100% (1)

- Cuadernillo de Nivelación de 1° AñoDocumento8 pagineCuadernillo de Nivelación de 1° Añobetina bNessuna valutazione finora

- World Languages: Secondary Solutions - Grades 6-12Documento45 pagineWorld Languages: Secondary Solutions - Grades 6-12Charlie NguyenNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan ICTDocumento3 pagineLesson Plan ICTAnthony RafolsNessuna valutazione finora

- Nali KaliDocumento19 pagineNali KaliNalini SahayNessuna valutazione finora

- St. Vincent de Ferrer College of Camarin, IncDocumento10 pagineSt. Vincent de Ferrer College of Camarin, IncNorman NarbonitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Engineering Degree PlanDocumento8 pagineEngineering Degree Planashvinbalaraman0Nessuna valutazione finora