Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Heat Related Disorders Abstract

Caricato da

Enida Xhaferi0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

28 visualizzazioni4 pagineHeat related pathologies are a group of disorders, associated with impairments of thermoregulation, which occur while individuals are exposed to high temperatures. The spectrum of these clinical entities ranges from syndromes with mild/moderate clinical manifestations, like heat edema/cramps/rash to the life-threatening heat stroke.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoHeat related pathologies are a group of disorders, associated with impairments of thermoregulation, which occur while individuals are exposed to high temperatures. The spectrum of these clinical entities ranges from syndromes with mild/moderate clinical manifestations, like heat edema/cramps/rash to the life-threatening heat stroke.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

28 visualizzazioni4 pagineHeat Related Disorders Abstract

Caricato da

Enida XhaferiHeat related pathologies are a group of disorders, associated with impairments of thermoregulation, which occur while individuals are exposed to high temperatures. The spectrum of these clinical entities ranges from syndromes with mild/moderate clinical manifestations, like heat edema/cramps/rash to the life-threatening heat stroke.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 4

Heat related disorders

Dr. Enida Xhaferi1, Dr. Altina Xhaferi2, Dr. Esmeralda Thoma1, Msc Miranda Cela1, Dr.

Fatbardha Lamaj3

1

University of Medicine/Faculty of Medical Technical Sciences, Tirana, Albania

2

Hygeia Hospital, Tirana, Albania

3

Intermedica Laboratory, Tirana, Albania

Heat related pathologies are a group of disorders, associated with impairments of

thermoregulation, which occur while individuals are exposed to high temperatures. The

spectrum of these clinical entities ranges from syndromes with mild/moderate clinical

manifestations, like heat edema/cramps/rash to the life-threatening heat stroke.

Heat accumulates in the body, when environmental exposure and metabolic needs are not

properly balanced by heat dissipating mechanisms. Factors that increase the risk of developing

heat related disorders include: presence of underlying medical conditions (like cardiovascular,

dermatologic, pulmonary diseases) use of medications, improper acclimatization, exposure to

very high temperatures/humidity, engaging outdoors in demanding exercise/work, lack of

physical fitness, wearing excessive clothing. Management of mild disorders is mainly

supportive, and associated adverse events occur rarely.

Heat stroke, on the other hand is a medical emergency, characterized by hyperthermia (rectal

core temperature ≥ 40°C) and central nervous dysfunction. The ensuing multiorgan injury and

hazardous complications, necessitate prompt diagnosis and thorough management. Rapid

cooling is the cornerstone of therapy. Techniques include cold water submersion, evaporative

cooling, complete body ice packing/local ice packing and application of invasive cooling

measures. Patients should be hospitalized and monitored carefully.

This short review aims to present the clinical manifestations and management of heat related

diseases. Despite all current medical advances, prevention remains the safest, most cost-

effective intervention for reducing incidence, morbidity and mortality, associated with these

pathologies.

Background. Humans are susceptible to high temperatures and heat stress. According to CDC,

in the USA, there have been 7046 deaths, attributable to excessive heat exposure, for the time

period between 1979 and 1997.

Heat is toxic to cells. Very high cellular temperatures lead to injury, disruption of cellular

pathways and biochemical reactions, denaturation of proteins and ultimate cell death. Heat

stress is associated with the release of inflammatory cytokines, interleukins and heat shock

proteins.

Acclimation (or acclimatization) to heat, involves a series of physiological adaptations, gained

during repeated exposure to high temperatures, which improve cardiovascular performance and

enhance other body heat coping mechanisms (increase capacity to produce sweat, improve salt

conservation by kidneys and sweat glands, boost activation of the renin–angiotensin–

aldosterone system, increase in glomerular filtration rate etc.).

Temperature regulation is negatively affected by hypothalamic dysfunction. Some other factors

which can interfere and reduce the efficacy of body’s heat elimination mechanisms include:

cardiovascular disorders, skin pathologies, high air temperatures/ ambient humidity, use of

some medicines, reduced ability for acclimatization, inadequate behavioral responses.

Heat related illnesses, are disorders resulting from the stress of responding to an excessive

thermal burden, where the body is unable to cope effectively with heat. Dysfunctional

thermoregulation derives from the inability to eliminate heat adequately. Heat illnesses

encompass a spectrum of conditions, varying form minor entities like heat edema/cramps/rash

to heat exhaustion/ syncope and the very hazardous life-threatening heat stroke.

There are two types of heat stroke: exertional heat illness (EHS) which affects primarily young

persons, mainly athletes, military personnel, outdoor workers and the classic, non-exertional

heat stroke (NEHS), involving elderly, sedentary individuals or the chronically ill. EHS is not

necessarily linked with heat waves (defined as a weather phenomenon, during which, for a

period of three or more days, the maximum shade temperature is ≥32.2°C) and is the leading

causes of death in young athletes each year. These two clinical entities have common clinical

manifestations, but are caused by differing underlying pathological mechanisms. Exertional

heat stroke occurs mainly when body’s heat elimination mechanisms are overwhelmed by

endogenous excessive heat production.

Objective. Present briefly the most common heat related illnesses and measures that should

be taken to manage them effectively and prevent future occurrences.

Methods. A literature review was conducted. Pathophysiology, clinical manifestations,

recommended therapeutic interventions were analyzed, organized and summarized below.

Results. In general, heat related disorders are due to the following factors: surplus heat

exposure from environment; an incompetence of the body’s cooling mechanisms to eliminate

heat or a combination of these two variables.

Heat edema involves a temporary swelling of the extremities (feet, ankle, hands), some few

days after heat exposure. Lower extremities are typically affected, but fluid can accumulate in

any other body’s dependent area. Peripheral vasodilation, venous stasis and increased water

retention from secondary aldosterone secretion are the main components of this benign

condition’s pathology, which occurs in poorly acclimatized individuals, exposed to high

temperatures. It is important to exclude other systemic causes of edema. Heat edema requires

no specific treatment and the disorder will resolve spontaneously after acclimatization.

Elevation of extremities helps.

Heat cramps are painful involuntary spasms of the heavily worked, large muscle groups, which

are used during exertion. They are the result of electrolytes’ loss in sweating (a very important

heat dissipation mechanism). Heat cramps are short lived, involve specific muscles and almost

never cause rhabdomyolisis. Management includes fluid and salt replacement, massage, stretch

and rest in cool environment. Drinking electrolyte beverages and maintaining adequate dietary

salt intake helps prevent their occurrence.

Heat rash is a maculopapular rash, characterized by inflammation and blockage of sweat ducts,

affecting both children and adults. Sweat ducts may become dilated and rupture into the dermis,

developing thus, consecutive dermatitis or a secondary bacterial infection. Use of loose-fitting

clothes is recommended and chlorhexidine cream or salic acid cleaning of lesions, might be

useful. Antibiotics should be applied when infection develops.

Heat syncope occurs usually after exercising and is due to postural hypotension, resulting from

volume depletion, peripheral vasodilation, and decreased vasomotor tone. Patients should be

evaluated for injuries that may have resulted from the falls that accompany usully syncopal

episodes. Treatment involves cooling and oral or intravenous rehydration.

Heat exhaustion is the most common heat related illness, marked by excessive dehydration,

electrolyte depletion, and decreased cardiac output. Patient’s mental status remains intact and

his core body temperature rarely exceeds 40°C. Common symptoms include headaches,

tachycardia, malaise nausea, dizziness. Treatment consists of cooling, oral or intravenous

rehydration.

Individuals with heat exhaustion should be evaluated and managed in the emergency

department, where laboratory studies (comprising - complete blood count, coagulation studies,

urinalysis, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests) should be carried out and vital signs

monitored.

Heat stroke is the most severe form of heat related disorders. Both types - classic and exertional

heat stroke, are characterized by core body temperature > 40 °C and neurologic abnormalities

(irritability, confusion, delirium, inappropriate behavior, seizures). Other symptoms that

patients might have include: anhidrosis or excessive sweating, tachycardia, tachypnea,

hypotension.

Heat stroke occurs when heat load is not modulated properly. Pathophysiology is complex, and

the combination of severe physiological alterations and biochemical reactions contribute to the

creation of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SISR; similar to septic shock),

which might cause rapid deterioration of patient’s clinical situation, multiorgan failure and

subsequent death.

Heat stroke treatment should be carried out on site and in the emergency department. Patient’s

airway, breathing, and circulation should be maintained, and cooling, which is the cornerstone

of therapy, should ensue rapidly. Cooling techniques include - cooling by evaporation,

immersion cooling, applying ice packs, invasive cooling measures and other cooling methods.

It is important to apply resuscitation measures, monitor patient’s situation and manage

complications promptly.

Conclusions. Heat disorders comprise a group with both mild and severe illnesses. There are

many factors, which can disrupt body’s heat elimination mechanisms (like cardiac conditions,

taking certain medications/diuretic therapy, anihidrosis) and increase the risk for development

of heat illnesses. Heat stroke is a very hazardous condition. It is important that individuals take

immediate action when they feel uncomfortable heat and avoid risks underestimation.

Some important interventions which could help avoid serious, future illnesses include: being

aware of personal/environmental risk factors, applying acclimation protocols for personnel that

works/exercises outdoors, avoiding strenuous exercise, as indicated by the heat index chart

guidelines, drinking plenty of fluids and avoiding alcohol, wearing light and loose fitting

clothes, taking advantage of shaded/air conditioned areas. Medicine is advancing but for this

entity like for the many other medical disorders, prevention is just better than the cure.

References

1. Leon LR, Bouchama A. Heat stroke. Compr Physiol 2015; 5:611-47.

2. Knochel JP. Catastrophic medical events with exhaustive exercise: “white collar rhabdomyolysis.” Kidney Int 1990;

38:709-19.

3. Gabay C, Kushner I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N Engl J Med 1999;

340:1376.

4. Heat-related illnesses, deaths, and risk factors — Cincinnati and Dayton, Ohio, 1999, and United States, 1979–1997.

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2000; 49:470-3.

5. Epstein Y., Yanovich R., Heat Stroke N. Engl J Med 2019; 380;25; 2449-2459.

6. Bouchama A, Knochel JP. Heat stroke. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:1978-88.

7. Shapiro Y, Seidman DS. Field and clinical observations of exertional heat stroke patients. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1990;

22:6-14.

8. Jardine DS., Heat illness and heat stroke, Pediatr Rev. 2007;28(7):249‐258.

9. Yang YL, Lin MT. Heat shock protein expression protects against cerebral ischemia and monoamine overload in rat

heatstroke. Am J Physiol 1999;276:H1961-H1967.

10. Wang ZZ, Wang CL, Wu TC, Pan HN, Wang SK, Jiang JD. Autoantibody response to heat shock protein 70 in patients

with heatstroke. Am J Med 2001; 111:654-7.

11. Lipman GS, Eifling KP, et al., Wilderness Medical Society practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of heat-

related illness. Wilderness Environ Med. 2013 Dec. 24(4):351-61.

12. Bouchama A, Knochel JP. Heat stroke. N Engl J Med. 2002 Jun 20. 346 (25):1978-88.

13. Pedersen BK, Hoffman-Goetz L. Exercise and the immune system: regulation, integration, and adaptation. Physiol Rev

2000; 80:1055-81.

14. Moseley PL. Heat shock proteins and heat adaptation of the whole organism. J Appl Physiol 1997; 83:1413-7.

15. Beal AL, Cerra FB. Multiple organ failure syndrome in the 1990s: systemic inflammatory response and organ

dysfunction. JAMA 1994; 271:226-33.

16. American College of Sports Medicine Joint Statement. National Athletic Trainers' Association. Inter-Association Task

Force on Exertional Heat Illnesses Consensus Statement. 2003.

17. Mazerolle SM, Pinkus DE, et al. Evidence-based medicine and the recognition and treatment of exertional heat stroke,

part II: a perspective from the clinical athletic trainer. J Athl Train. 2011 Sep-Oct. 46(5):533-42.

18. Mazerolle SM, Ganio MS, et al. Is oral temperature an accurate measurement of deep body temperature? A systematic

review. J Athl Train. 2011 Sep-Oct. 46(5):566-73.

Bibliography

Enida Xhaferi has finished Medical School at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Tirana, in July 2002

and completed Clinical Rheumatology residency in Tirana, in March 2007. She has been working for the

University of Medicine of Albania since 2010, where she teaches Internal Medicine and Management of

Patients during Disasters.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Heat Related Disorders Abstract PDFDocumento4 pagineHeat Related Disorders Abstract PDFEnida XhaferiNessuna valutazione finora

- E-Therapeutics+ - Minor Ailments - Therapeutics - Central Nervous System Conditions - Heat-Related DisordersDocumento7 pagineE-Therapeutics+ - Minor Ailments - Therapeutics - Central Nervous System Conditions - Heat-Related DisordersSamMansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- Environmental Factors and DiseasesDocumento27 pagineEnvironmental Factors and DiseasesSHIHAB UDDIN KAZINessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 49 Heat InjuriesDocumento8 pagineChapter 49 Heat Injuriessmith.kevin1420344Nessuna valutazione finora

- Environmental Emergencies ParamedicDocumento90 pagineEnvironmental Emergencies ParamedicPaulhotvw67100% (2)

- Emergency Manajement and EffectDocumento8 pagineEmergency Manajement and EffectTitik ErawatiNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal Heat DisorderDocumento8 pagineJurnal Heat DisorderDiatri Eka DentaNessuna valutazione finora

- Diagnosis and Management of Heatstroke: I Gede Yasa AsmaraDocumento8 pagineDiagnosis and Management of Heatstroke: I Gede Yasa AsmaraputryaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cold and Heat Therapy 护理学院朱晓雯(以此版本为准)Documento24 pagineCold and Heat Therapy 护理学院朱晓雯(以此版本为准)sargunavalli balrajNessuna valutazione finora

- Exertional Heatstroke, Asesmen Cepat Dan Penatalaksanaan Tepat: Laporan KasusDocumento18 pagineExertional Heatstroke, Asesmen Cepat Dan Penatalaksanaan Tepat: Laporan KasusGreen HanauNessuna valutazione finora

- Signs and Symptoms: Hyperthermia Is An Elevated Body Temperature Due To FailedDocumento6 pagineSigns and Symptoms: Hyperthermia Is An Elevated Body Temperature Due To FailedbabykhoNessuna valutazione finora

- Heat StrokeDocumento15 pagineHeat Strokevague_darklordNessuna valutazione finora

- HyperthermiaDocumento20 pagineHyperthermiaShereen AlobinayNessuna valutazione finora

- Thermal Regulation: Mary Frances D. PateDocumento17 pagineThermal Regulation: Mary Frances D. PateWinny Shiru MachiraNessuna valutazione finora

- HyperthermiaDocumento40 pagineHyperthermiaqaisersiddi100% (2)

- Heat Stroke in Dogs Literature ReviewDocumento11 pagineHeat Stroke in Dogs Literature ReviewGuillermo MuzasNessuna valutazione finora

- Fev Mech PDFDocumento7 pagineFev Mech PDFMitzu AlparisNessuna valutazione finora

- Exertional Heatstroke, Asesmen Cepat Dan Penatalaksanaan:: Laporan KasusDocumento17 pagineExertional Heatstroke, Asesmen Cepat Dan Penatalaksanaan:: Laporan KasusAndhika RcmNessuna valutazione finora

- Heat Stroke: Ann Disaster Med Vol 2 Suppl 2 2004Documento13 pagineHeat Stroke: Ann Disaster Med Vol 2 Suppl 2 2004AniNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal Reading (Heat Stroke)Documento24 pagineJournal Reading (Heat Stroke)Adinda WidyantidewiNessuna valutazione finora

- Nur 111 Session 21 Sas 1Documento8 pagineNur 111 Session 21 Sas 1Zzimply Tri Sha UmaliNessuna valutazione finora

- 4 9 Heat Stroke PDFDocumento6 pagine4 9 Heat Stroke PDFmia nurjanahNessuna valutazione finora

- 2.2 Workplace Health HazardDocumento21 pagine2.2 Workplace Health HazardMarianne BallesterosNessuna valutazione finora

- Dealing With Heat StressDocumento11 pagineDealing With Heat StressIlyes FerenczNessuna valutazione finora

- Garispanduan Pengurusan Kes-Kes Yang Berkaitan Dengan Cuaca PanasDocumento21 pagineGarispanduan Pengurusan Kes-Kes Yang Berkaitan Dengan Cuaca PanasHong Wei LungNessuna valutazione finora

- Environmental Cold Injury and Illness Prevention PolicyDocumento12 pagineEnvironmental Cold Injury and Illness Prevention Policyapi-381026050Nessuna valutazione finora

- HIPOTERMIADocumento6 pagineHIPOTERMIARonald Silva CarranzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Heat Stress Management ProcedureDocumento7 pagineHeat Stress Management ProcedureSameer M. TalibNessuna valutazione finora

- Fever: Anca Ba Cârea, Alexandru SchiopuDocumento24 pagineFever: Anca Ba Cârea, Alexandru SchiopuAndika GhifariNessuna valutazione finora

- Alteration in Body TemperatureDocumento19 pagineAlteration in Body Temperaturepravina praviNessuna valutazione finora

- HypothermiaDocumento4 pagineHypothermiabadamasimusa20Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hi Perter MiaDocumento8 pagineHi Perter MiaPedro Luz da RosaNessuna valutazione finora

- 5.paparan PanasDocumento36 pagine5.paparan PanasMarta Juwita SitumorangNessuna valutazione finora

- Hot & Cold TempDocumento20 pagineHot & Cold TempdeepuphysioNessuna valutazione finora

- Heat HealthDocumento8 pagineHeat HealthSohailNessuna valutazione finora

- IM361B-PathPhysio Orals 2020Documento95 pagineIM361B-PathPhysio Orals 2020Mi PatelNessuna valutazione finora

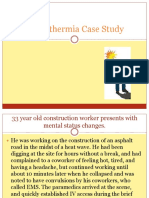

- Hyperthermia Case StudyDocumento28 pagineHyperthermia Case StudyJanelle GimenezNessuna valutazione finora

- Group 4 - Bacani - 220000002117Documento3 pagineGroup 4 - Bacani - 220000002117Ana Paula Bacani-SacloloNessuna valutazione finora

- Heat SrokeDocumento8 pagineHeat SrokeChristy BradyNessuna valutazione finora

- COMPILATION ON ENVIRONMENTAL DISEASES by Aditi AryaDocumento15 pagineCOMPILATION ON ENVIRONMENTAL DISEASES by Aditi AryaGogi HotiNessuna valutazione finora

- 66.regulation of Body TemperatureDocumento4 pagine66.regulation of Body TemperatureNek TeroNessuna valutazione finora

- Environment Related ConditionsDocumento59 pagineEnvironment Related Conditionsbrida.bluesNessuna valutazione finora

- Altered Body Temperature: Presented By: Navjeet Kaur M.SC (NSG) 1 YRDocumento68 pagineAltered Body Temperature: Presented By: Navjeet Kaur M.SC (NSG) 1 YRNithu NithuNessuna valutazione finora

- Heat StrokeDocumento2 pagineHeat StrokeTomas Cordia CornelioNessuna valutazione finora

- PNTC Colleges: Senior High SchoolDocumento7 paginePNTC Colleges: Senior High SchoolRodolfo CalindongNessuna valutazione finora

- Heat Stroke ArticleDocumento29 pagineHeat Stroke ArticleIurascu GeaninaNessuna valutazione finora

- Heat Stroke and Heat ExhausDocumento46 pagineHeat Stroke and Heat ExhausDewi Pertiwi Pertiwi0% (1)

- Frostbite and HypothermiaDocumento43 pagineFrostbite and HypothermiaBlade DarkmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Cstafford - Hypothermia and Hyperthermia - 06072018Documento4 pagineCstafford - Hypothermia and Hyperthermia - 06072018Charlene StaffordNessuna valutazione finora

- General Physiology: Samina AhmadDocumento23 pagineGeneral Physiology: Samina AhmadMuhammad bilalNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study-HomeostasisDocumento2 pagineCase Study-HomeostasisAllaika Zyrah FloresNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal 5 BaruDocumento15 pagineJurnal 5 BaruichamarichaNessuna valutazione finora

- Heat and Cold Therapy PPT 17Documento54 pagineHeat and Cold Therapy PPT 17sargunavalli balrajNessuna valutazione finora

- Heat StressDocumento22 pagineHeat Stressigor_239934024Nessuna valutazione finora

- Environmental EmergenciesDocumento38 pagineEnvironmental EmergenciesIshaBrijeshSharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- FeverDocumento16 pagineFeverRoquiyaKhushbooNessuna valutazione finora

- Hypothermia and Temperature Regulation Considerations During AnesthesiaDocumento15 pagineHypothermia and Temperature Regulation Considerations During AnesthesiaJoško IvankovNessuna valutazione finora

- Background: Therapeutic HypothermiaDocumento11 pagineBackground: Therapeutic HypothermiaDella Putri Ariyani NasutionNessuna valutazione finora

- Enfermedades Relacionadas Al CalorDocumento12 pagineEnfermedades Relacionadas Al CalorJennifer Gonzalez NajeraNessuna valutazione finora

- Dentinal HypersensitivityDocumento11 pagineDentinal HypersensitivityAmira KaddouNessuna valutazione finora

- Scientific Method ReadingDocumento4 pagineScientific Method Readingrai dotcomNessuna valutazione finora

- Rheumatic Heart Disease: Presented by Dr. Thein Tun 2 DR.D.SC (Oral Medicine)Documento22 pagineRheumatic Heart Disease: Presented by Dr. Thein Tun 2 DR.D.SC (Oral Medicine)dr.thein tunNessuna valutazione finora

- Krok 2 2017Documento30 pagineKrok 2 2017slyfoxkitty67% (3)

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Rotary Niti Advantages DisadvantagesDocumento3 pagineAdvantages and Disadvantages of Rotary Niti Advantages DisadvantagesheenalvNessuna valutazione finora

- Im Irritable Bowel Syndrome Intestinal Obstruction Acute Appendicitis Lecture TransDocumento6 pagineIm Irritable Bowel Syndrome Intestinal Obstruction Acute Appendicitis Lecture TransMelissa LabadorNessuna valutazione finora

- Iccms Caries Prevention and TreatmentDocumento3 pagineIccms Caries Prevention and TreatmentJOHN HAROLD CABRADILLANessuna valutazione finora

- PSM (Must Know)Documento19 paginePSM (Must Know)PranavNessuna valutazione finora

- Antenatal Assessment - Case No-1Documento4 pagineAntenatal Assessment - Case No-1Prity DeviNessuna valutazione finora

- Station 5Documento25 pagineStation 5adi mustafaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sepsis 3Documento38 pagineSepsis 3EvanNessuna valutazione finora

- 2017 Soal UAS - M. Operasional. - Bpk. Agustinus S PDFDocumento3 pagine2017 Soal UAS - M. Operasional. - Bpk. Agustinus S PDFraymunandarNessuna valutazione finora

- Usability Best PracticesDocumento37 pagineUsability Best PracticesMashal PkNessuna valutazione finora

- LogbookDocumento9 pagineLogbookforriskyguyNessuna valutazione finora

- For The Best Sinus Congestion RemediesDocumento4 pagineFor The Best Sinus Congestion Remedies4zaleakuNessuna valutazione finora

- American Indian: Health DisparitiesDocumento13 pagineAmerican Indian: Health DisparitiesDarwinso AlvarezNessuna valutazione finora

- Use of Alternative Medicine To Manage Pain: (CITATION Har16 /L 1033)Documento6 pagineUse of Alternative Medicine To Manage Pain: (CITATION Har16 /L 1033)Syed Muhammad Baqir RazaNessuna valutazione finora

- 4 - Pharmaceutical ProcurementDocumento12 pagine4 - Pharmaceutical ProcurementRazak KiplangatNessuna valutazione finora

- Application Form Health Examination Form Parents Consent FormDocumento1 paginaApplication Form Health Examination Form Parents Consent Formapril rose catainaNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study On SEPSIS 2' ACP PneumoniaDocumento7 pagineCase Study On SEPSIS 2' ACP Pneumoniajcarysuitos100% (2)

- Interproximal Enamel Reduction As A Part of Orthodontic TreatmentDocumento6 pagineInterproximal Enamel Reduction As A Part of Orthodontic Treatmentdrgeorgejose7818Nessuna valutazione finora

- Primary Survey & Secondary Survey: Presentor: Shellazianne Anak Ringam Date: 20 November 2015Documento27 paginePrimary Survey & Secondary Survey: Presentor: Shellazianne Anak Ringam Date: 20 November 2015Keluang Man WinchesterNessuna valutazione finora

- Media Children Indpendent Study-4-2Documento21 pagineMedia Children Indpendent Study-4-2api-610458976Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lecture-25 Cesarean SectionDocumento21 pagineLecture-25 Cesarean SectionMadhu Sudhan PandeyaNessuna valutazione finora

- تجميعات سعيد لشهر نوفمبرDocumento125 pagineتجميعات سعيد لشهر نوفمبرHana kNessuna valutazione finora

- Day 5-Vincent Cheung - QuestionDocumento6 pagineDay 5-Vincent Cheung - QuestionMRFKJ CasanovaNessuna valutazione finora

- Gonorrhea Case StudyDocumento2 pagineGonorrhea Case StudyDonna LLerandi100% (1)

- BONE Level 2-BDocumento60 pagineBONE Level 2-Bjefri banjarnahorNessuna valutazione finora

- Merge Live Online Nle Review 2021: Anatomy of The Nle (Nurse Licensure Examination)Documento13 pagineMerge Live Online Nle Review 2021: Anatomy of The Nle (Nurse Licensure Examination)Johnmer AvelinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Personalized MedicineDocumento3 paginePersonalized MedicinestanscimagNessuna valutazione finora