Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

1st Chapter Style and Choice

Caricato da

Samar SaadCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

1st Chapter Style and Choice

Caricato da

Samar SaadCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Style and Choice

1.1 The Domain of Style:

Style can be defined as the way by which language is used for a special purpose by a particular person

in a given context. To explain this concept, we can use Saussure's distinction between 'langue' and

'parole':

- Langue: the rules that are common to speakers of a particular language (e.g. English).

- Parole: the uses of these rules by speakers and writers in different occasions.

Style is a relational term. It has been applied to the linguistic habits of a particular writer, to the way

language is used in a particular genre, period, or school of writing. Furthermore, the term 'style' can be

applied to both spoken and written, both literary and non-literary varieties of language. But, usually, it is

associated with literary written texts. Thus, we can think of style as "the linguistic characteristics of a

particular text," and this is the domain of style.

1.2 Stylistics:

Stylistics is simply defined as "the linguistic study of style." Style is usually studied to explain

something. Thus, literary stylistics aims to explain the relation between language and its artistic

function. Its goal is "to relate the critic's concern of aesthetic appreciation with the linguist's concern of

linguistic description."

A question that is often asked is which comes first, the aesthetic or the linguistic? This question is

answered by Spitzer's 'philological circle'. There is a cyclic motion in which the linguistic observation

stimulates or modifies the literary insight, and in which the literary insight in its turn stimulates further

the linguistic observation. There is no logical starting point since we bring to a literary text two faculties:

our ability to respond to it as a literary work and our ability to observe its language.

1.3 Style and Content:

There are a number of approaches to style. The first one is the 'Dualist' approach which defines style

as a "way of writing " or a "mode of expression". These definitions imply a separation between

"manner" and "matter" or "expression" and "content". Another view sees form and content as one

thing. This view is called the 'Monist' view.

1.3.1 Style as the 'Dress of Thought' one kind of Dualism:

The earliest and the most persistent concept of style is the view that style is the 'dress of thought'.

Although this view is no longer widely current, it appears in Renaissance and rationalist

pronouncements of style. This is clear in Pope's well-known definition of wit:

‘True wit is nature to advantage dressed

What oft was thought but ne’er so well expressed’.

It is also clear in Wesley's definition:

‘Style is the dress of thought; a modern dress,

neat, but not gaudy, will true critics please’.

Dualists distinguish between what a writer has to say and how his thoughts are dressed to be

presented to the reader. The writer's choice of dressing his thoughts in a certain way implies certain

meanings; for example, the choice of using third-person pronouns is regarded as neutral in narration.

Yet the choice of such a neutral form is as much a linguistic choice as any other, and may have

implications which may be fruitfully examined in stylistics: the third-person pronoun, for example,

distances the author and the reader from the character it denotes.

It is hard to deny, from a common-sense reader’s point of view, that texts differ greatly in their

degree of stylistic interest or markedness; or that some texts are more ‘transparent’, in the sense of

showing forth their meaning directly, than others. But for all practical purposes, the idea of style as an

‘optional extra’ must be firmly rejected.

1.3.2. Style is a manner of expression:

This notion maintains that the style of each writer is determined by the choices of expression he

makes.

Here we can draw a distinction between monism and dualism; dualist maintains that the same content

can be conveyed in different ways. Monists maintain that any change of form entails a change of

meaning.

In order to prove this theory, Richard Ohmann, a modern dualist, argues that it is the grammatical

aspects (particularly the transformational grammatical Rules) not the lexical aspects that determine

style. These are rules which change the form of a basic sentence type without changing its lexical

content. Ohmann employed the device of reversing the effects of grammatical transformations to

produce kernel sentences to point the artistic value of these transformations.

Moreover, these Transformational rules provide a linguistic basis for the notion of paraphrase.

Sense + stylistic value = (total) significance

Paraphrase itself depends on the conception of "sense", the basic logical, conceptual, paraphrasable

meaning, and "significance", the total of what is communicated to the world by a given sentence.

Dualism assumes that one can paraphrase a sense of a text, and that there is a valid separation of sense

from significance. Still, Dualists do not treat stylistics as devoid of significance. Rather, they search for

some significance, STYLISTIC VALUE, in a writer's choice to express his sense in this or that way.

However there are difficulties with this version of dualism as well:

Some transformations don't preserve to the same "logical content"

Some girls are tall and some girls are short---- Some girls are tall and short.

However, Ohmann's approach still has a linguistic validity since the principle of paraphrase is held by

many linguistic schools.

In conclusion, the relation between transformations and meaning goes beyond being mere paraphrases.

Although Ohmann's detransforming technique provides the idea of stylistic neutrality, still the

detransformed passage cannot be said to be neutral or "styleless," because writing it in disconnected

sentences can be regarded as a stylistic choice.

1.3.3 Monism: the inseparability of style and content.

Monism finds it strongest ground in poetry where meaning becomes multivalued and sense loses

its primacy through metaphor, Irony, etc. Monism supports the New Critics who rejected the idea that a

poem conveys a message, preferring to see it as an autonomous verbal work of art.

The problems facing the dualist approach exist also in prose because according to them

1- It is impossible to paraphrase literary writing

2- It is impossible to translate a literary work

3- It is impossible to divorce the general appreciation of a literary work from the appreciation of its style.

Nevertheless, translating novels is possible though it loses some of its originality while monism

maintains that it is impossible to translate any literary work.

A new trend of criticism argues that criticism is a criticism of language, yet we can't separate the

creation of plot, character, etc. from the language in which it is portrayed. Language is the medium

through which the novelist does anything. Accordingly, there is no difference between the choice of the

writer to call a character dark or fair and the choice between synonyms such as dark and swarthy. All the

choices he makes are equally matters of language.

1.4. Comparing dualism and monism:

Whereas dualism seems happier with prose, monism seems happier with poetry. However, if the

difference between poetry and prose is defined by the absence and presence of verse, then some types

of poetry are more "prosaic" than others and some types of prose are more "poetic" than others. For a

further explanation of this point, Burgess proposes a division of novelists into two classes:

- Class I Novelist: is one in whose work language is a zero quality, transparent, unseductive that the

reader need not become consciously aware of the medium through which the sense is conveyed to him.

- Class II Novelist: is one for whom ambiguities and puns are to be enjoyed and whose books lose a great

deal when adapted to visual medium since the interpretation of sense may be frustrated and obstructed

by the abnormal lexical and grammatical features of the medium.

All in all we can't reject one of them and accept the other as each one of them has its minuses and

pluses. Actually, for most novels neither dualism nor monism will be satisfactory, there is a need for

something that avoids the weaknesses of both.

1.5 Pluralism: Analyzing Style In Terms of Functions:

An alternative to monism and dualism is the approach called stylistic pluralism. The pluralist holds

that language performs a number of different functions, and any piece of language is the result of

choices made on different functional levels. Hence, the pluralist isn’t content with the dualist’s division

between “expression” and “content” as he wants to distinguish various standards of meaning according

.to the various functions

That language can perform varied functions or communicative roles is a commonplace of linguistic

thought. The popular assumption that language simply serves to communicate “thoughts” or “ideas” is

too simplistic. Some kinds of language have a referential function (newspaper reports), others have a

directive or persuasive function (advertizing), others have an emotive or social function (casual

conversation). To this general appreciation of functional variety in language, the pluralist adds the idea

that language is multifunctional, so that the simplest utterance conveys more than one kind of meaning.

For example, “is your father feeling better?” may be referential (referring to a person and his illness),

directive (demanding a reply from the hearer) or social (showing sympathy between the speaker and

hearer). From this viewpoint, the dualist is wrong in assuming that there is some unitary conceptual

.“content” in every piece of language

Of the many functional classifications of language that have been proposed, three have had some

:currency in literary studies

Richards in “Practical Criticism” distinguishes 4 types of function and 4 kinds of meaning: sense, -1

.feeling, tone and intention

Jakobson’s distinguishes 6 functions: referential, emotive, conative, phatic, poetic, and metalinguistic. -2

.3- Halliday acknowledges 3 major functions: ideation, interpersonal and textual

It is clear that pluralists disagree on what the functions are and even on their number and how

these functions are manifested in literary language. Richards holds that in poetry the function of feeling

tends to dominate that of “sense” but Jacobson identifies a special “poetic” function which dominates

.over other functions in poetry

Halliday holds that different kinds of literary writing may foreground different functions. Halliday’s

analysis of Golding’s The Inheritors shows the relation of pluralism to dualism and monism. (a passage)

Halliday’s analysis is revealing in the way it relates precise linguistic observation to literary effect. Its

interest is that it locates stylistic significance in the ideational function of language; that is in the

cognitive meaning or sense which for the dualist is the invariant factor of content rather than the

variable factor of style. For Ohmann, the choice between: A stick rose upright’ and ‘He raised his bow’

isn’t a matter of style as these sentences contrast grammatically in terms of phrase structure and hence,

.they aren’t paraphrases of each other

There is thus incompatibility between the pluralist and the dualist. Comparing Ohmann and Halliday as

:representatives of these two schools

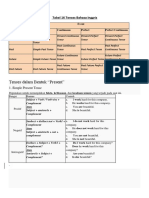

Halliday (1970) Ohmann (1964)

Ideational function Content (phrase Structure)

Textual function Expression (optional transformation)

C- Interpersonal function --------------------------------------

For Ohmann, style belongs to level B, but for Halliday, style can be located in A, B or C. the

interpersonal function shows the relation between language and its users and combines two categories

which are often kept separate in functional models: the affective or emotive function (communicating

.the speaker’s attitudes) and the directive function (influencing the behavior and attitudes of the hearer)

Halliday’s view is that all linguistic choices are meaningful and all linguistic choices are stylistic. In

this respect, Halliday’s pluralism is a more sophisticated version of monism. The flaw of monism is that it

tends to view a text as an undifferentiated whole, so that examination of linguistic choices can’t be

made except on some ad hoc principle. One can argue that the monist can’t discuss language at all: if

meaning is inseparable from form, one can’t discuss meaning without repeating the same words in

which it is expressed and one can’t discuss form except by saying that it expresses its own meaning. But

the pluralist is in a happier position; he can show how choices of language are interrelated within the

network of functional choices. What choices a writer makes can be seen against the background of

relations of contrast and dependence between one choice and another such as the choice between

transitive and intransitive verbs. That’s to say that the pluralist has a theory of language whereas the

.monist doesn’t

:A Multilevel Approach To Style 1.6

Halliday’s pluralism is superior to both monism and dualism. Dualism can say nothing about how

language creates a particular cognitive view of things, what Fowler calls Mindstyle. Thus, dualism

.excludes much that is worthy of attention in modern fiction writing

Both monism and pluralism are more suited to opacity than to transparency. Halliday discusses

The Inheritors against the background of the theory of foregrounding and Golding’s Lok-language in its

opacity bears some resemblance to the language of child Stephen in Joyce’s portrait. In both cases, the

author shocks us into an unfamiliar mode of expression, by using language suggestive of a primitive

.state of consciousness

What is good in the dualist’s position is that he shows that two pieces of language can be seen as

alternative ways of saying the same thing, that there can be stylistic variants with different stylistic

.values

Halliday’s approach is hard to reconcile with this everyday insight about style. For him, even

choices which are dictated by subject matter are part of style: it is part of style about a particular

cookery book that it contains words like butter, flour, boil and bake, and it is part of style of Animal Farm

that it contains words like farm, pigs and Napoleon. Even choice of proper names or of whether to call a

character fair or dark-haired is a matter of style_ in this the Pluralist Halliday must agree with the monist

.Lodge

Applied to non-fictional language, this position fails to make an important discrimination. In a

medical textbook, the choice between clavicle and collar-bone can justly be called a matter of stylistic

variation. But if the author replaced clavicle by thighbone, this is no longer a matter of stylistic variation,

but a matter of fact, and of potential disaster to the patient. There is no reason to treat fictional

language in a totally different way. The referential, truth-functional nature of language isn’t in use in

.fiction, rather it is exploited in referring to, and thereby creating a fictional universe, a mock-reality

At the referential level, Golding’s sentences: The Stick began to grow shorter at both ends. Then it

shot out to full length again. Tell the same story as: Lok saw the man draw the bow and release it.

Although these aren’t paraphrases, they can be regarded as stylistic variants in a more liberal sense as

.ways of making sense of the same event

It is important to understand that language is used in fiction to project a world “beyond

language”, in that we use not only our knowledge of language, the meanings of words but also our

.knowledge of real world to furnish it

It is reasonable to say that some aspects of language have the referential function of language,

and some others have to do with stylistic variation. If Golding had replaced ‘bushes’ with ‘reeds’ and

.river with ‘pond’, this wouldn’t have been stylistic variation but a change in the fictional world

What is good in the dualist’s position is that it allows for more than one level of stylistic variation.

The traditional term “content” fails to discriminate between ‘sense’ and reference’: what a linguistic

form means and what it refers to. Taking into account this discrimination, there can be alternative

.conceptualizations of the same event and alternative syntactic expressions of the same sense

Fiction is an invariant element, i.e. it must be taken for granted. The author is free to order his

universe as he wants, but for purposes of stylistic variations, we are only interested in those choices of

.language which don’t involve changes in the fictional universe

In this light, the view of Lodge, that whatever the novelist does, he does in and through language”

is attractive but misleading. This is because the novel has a more abstract level of existence, which in

principle is partly independent of the language through which it is represented and may be realized

through the visual medium of film. In support of this, two distinct kinds of descriptive statement can be

made about a verbal work of art. On the one hand, it can be described as: x contains simple words, more

abstract than concrete nouns, x is written in ornate, vigorous or colloquial language, or it can be

described in a way void of any linguistic dimension: x contains Neanderthal characters, x is about a

.woman who kills her husband, x is about events which take place in 19th C Africa

A Novel, therefore, has these two interrelated modes of existence_as a fiction and as a text, and

to adapt Lodge’s view: it is as text-maker that the novelist works in language, and it is as fiction-maker

that he works through language. This view distinguishes between ‘what one has to say’ and ‘how one

.’says it

:Conclusion: Meanings of Style 1.7

1- Style is a way in which language is used: i.e. it belongs to parole rather than to langue.

2- Style consists in choices made from the repertoire of the language.

3- Style is defined in terms of a domain on language use.

4- Stylistics has typically been concerned with literary language.

5- Literary stylistics is typically concerned with explaining the relation between style and literary or

aesthetic function.

6- Style is relatively transparent or opaque; transparency implies paraphrasability and opacity implies

that a text can’t be adequately paraphrased and the interpretation of the text depends on the creativity

of the reader.

7- Stylistic choice is limited to those aspects of linguistic choice which concern alternative ways of

rendering the same subject matter.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Bautista Book A PDFDocumento141 pagineBautista Book A PDFGrace Austria100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- 1954 The Science of Learning and The Art of TeachingDocumento11 pagine1954 The Science of Learning and The Art of Teachingcengizdemirsoy100% (1)

- Strategic Planning For Public and Nonprofit Organizations: John M Bryson, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USADocumento7 pagineStrategic Planning For Public and Nonprofit Organizations: John M Bryson, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USAMaritza Figueroa P.100% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Functions of IntonationDocumento10 pagineFunctions of IntonationSamar SaadNessuna valutazione finora

- 4th Chapter Levels of StyleDocumento4 pagine4th Chapter Levels of StyleSamar Saad0% (1)

- Experiencing The Lifespan 4th Edition Belsky Test Bank DownloadDocumento26 pagineExperiencing The Lifespan 4th Edition Belsky Test Bank DownloadJoy Armstrong100% (30)

- StressDocumento13 pagineStressSamar SaadNessuna valutazione finora

- Vowels of English: Presented by Marwa Mahmoud Abd El FattahDocumento5 pagineVowels of English: Presented by Marwa Mahmoud Abd El FattahSamar SaadNessuna valutazione finora

- Consonants of English: Presented by Marwa Mahmoud Abd El FattahDocumento8 pagineConsonants of English: Presented by Marwa Mahmoud Abd El FattahSamar Saad100% (2)

- Cardinal Vowels: Presented by Marwa Mahmoud Abd El FattahDocumento4 pagineCardinal Vowels: Presented by Marwa Mahmoud Abd El FattahSamar SaadNessuna valutazione finora

- 7th Chapter Part 1Documento11 pagine7th Chapter Part 1Samar Saad100% (1)

- 8th ChapterDocumento7 pagine8th ChapterSamar SaadNessuna valutazione finora

- 7th Chapter Part 2Documento8 pagine7th Chapter Part 2Samar SaadNessuna valutazione finora

- 8th Chapter Part 2Documento5 pagine8th Chapter Part 2Samar SaadNessuna valutazione finora

- 9th Chapter Conversation in The Novel Second PartDocumento4 pagine9th Chapter Conversation in The Novel Second PartSamar SaadNessuna valutazione finora

- 2nd Chapter Style Text and FrequencyDocumento6 pagine2nd Chapter Style Text and FrequencySamar Saad100% (6)

- 6th Chapter Mind StyleDocumento4 pagine6th Chapter Mind StyleSamar Saad100% (1)

- 5th Chapter Language and The Fictional WorldDocumento6 pagine5th Chapter Language and The Fictional WorldSamar Saad100% (2)

- Ezra PoundDocumento265 pagineEzra PoundSamar SaadNessuna valutazione finora

- Oral Com. G 11 Week 1 2 2Documento8 pagineOral Com. G 11 Week 1 2 2Kimaii PagaranNessuna valutazione finora

- GordanDocumento5 pagineGordanSania ZafarNessuna valutazione finora

- Faire - Do, Make - Essential French Verb - Lawless French GrammarDocumento7 pagineFaire - Do, Make - Essential French Verb - Lawless French Grammarnoel8938lucianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Bus 5211 Unit 3 DiscussionDocumento5 pagineBus 5211 Unit 3 DiscussionmahmoodNessuna valutazione finora

- Itl 520 Week 1 AssignmentDocumento7 pagineItl 520 Week 1 Assignmentapi-449335434Nessuna valutazione finora

- Dictogloss As An Interactive MethodDocumento12 pagineDictogloss As An Interactive Methodbuson100% (1)

- 12 Angry Men Reflection PaperDocumento3 pagine12 Angry Men Reflection PaperAngelie SaavedraNessuna valutazione finora

- StorySelling Secrets by PGDocumento32 pagineStorySelling Secrets by PGTimileyin AdesoyeNessuna valutazione finora

- Super Teacher Worksheets Crossword PuzzleDocumento4 pagineSuper Teacher Worksheets Crossword PuzzleSolit - Educational OrganizationNessuna valutazione finora

- Field Study 2 Experiencing The TeachingDocumento70 pagineField Study 2 Experiencing The Teachingjeralyn AmorantoNessuna valutazione finora

- Improving Memory and Study Skills: Advances in Theory and PracticeDocumento14 pagineImproving Memory and Study Skills: Advances in Theory and PracticeWajid HusseinNessuna valutazione finora

- Activity NCM 117Documento6 pagineActivity NCM 117Yeany IddiNessuna valutazione finora

- Intervention Assessment For EffectiveDocumento12 pagineIntervention Assessment For EffectiveDiana Petronela AbabeiNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 3Documento12 pagineChapter 3Ngân Lê Thị KimNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Proposal and Seminar On Translation - VDocumento3 pagineResearch Proposal and Seminar On Translation - VRi On OhNessuna valutazione finora

- Siddhi - Saraf - Resume - 02 12 2022 19 13 57Documento2 pagineSiddhi - Saraf - Resume - 02 12 2022 19 13 57akash bhagatNessuna valutazione finora

- Summarizing vs. Paraphrasing: A PowerPointDocumento9 pagineSummarizing vs. Paraphrasing: A PowerPointStacie Wallace86% (7)

- Tabel 16 Tenses Bahasa InggrisDocumento8 pagineTabel 16 Tenses Bahasa InggrisAnonymous xYC2wfV100% (1)

- Code SwitchingDocumento19 pagineCode SwitchingrifkamsNessuna valutazione finora

- FD Chapter 1 Excerpt AnalysisDocumento13 pagineFD Chapter 1 Excerpt Analysisapi-305845489Nessuna valutazione finora

- Problem Solving & Decision Making at NTPCDocumento32 pagineProblem Solving & Decision Making at NTPCJanmejaya MishraNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Self-Concept Theory? A Psychologist Explains.: Skip To ContentDocumento30 pagineWhat Is Self-Concept Theory? A Psychologist Explains.: Skip To ContentandroNessuna valutazione finora

- Grade 12-Creative Nonfiction Week 2 Las 1Documento1 paginaGrade 12-Creative Nonfiction Week 2 Las 1Gladys Angela Valdemoro100% (1)

- W07 iBT KAPLAN-1Documento22 pagineW07 iBT KAPLAN-1GolMalNessuna valutazione finora

- Revised Bloom's Taxonomy VerbsDocumento1 paginaRevised Bloom's Taxonomy VerbsRoseann Hidalgo ZimaraNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Learn EnglishDocumento3 pagineHow To Learn Englishari mulyadiNessuna valutazione finora