Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

CT of A Thickened-Wall Gall Bladder

Caricato da

drrahulsshindeTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

CT of A Thickened-Wall Gall Bladder

Caricato da

drrahulsshindeCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The British Journal of Radiology, 76 (2003), 137–143 E 2003 The British Institute of Radiology

DOI: 10.1259/bjr/63382740

Pictorial review

CT of a thickened-wall gall bladder

1

R ZISSIN, MD, 1A OSADCHY, MD, 1M SHAPIRO-FEINBERG, MD and 2G GAYER, MD

1

Department of Diagnostic Imaging, Sapir Medical Center, Kfar Saba 44281 and 2Department of Diagnostic Imaging,

Assaf Harofe Medical Center, Zrifin, affiliated to the Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv, Israel

Abstract. This pictorial article reviews the various clinical entities that may cause mural thickening of the

gall bladder encountered on contrast enhanced CT.

The current widespread use of abdominal CT has Acute cholecystitis

resulted in the detection of various pathological processes,

CT may be used for the evaluation of patients with

that cause thickening of the gall bladder (GB) wall.

acute right upper quadrant (RUQ) complaints with

On contrast enhanced CT, the normal GB wall is

inconclusive ultrasound findings or with a perplexing

usually perceptible as a thin enhancing rim of soft tissue

density. Although its thickness depends upon the degree clinical presentation when acute cholecystitis is not the

of GB distention, 3 mm is regarded as the upper limit of first diagnostic choice, but may be the first modality to

normal and mural thickening is defined as a transverse detect it.

wall measurement of 4 mm or greater [1]. GB wall Thickening of the GB wall is the most common finding

thickening is the most common finding in either acute of acute cholecystitis (Figures 1, 2, 3a) while gallstones

calculus or acalculous cholecystitis [2, 3]. It is a non- may or may not be seen [2, 3]. In fact, 95% of patients with

specific finding that may be seen in GB cancer and in a acute cholecystitis have gallstones, but only approximately

variety of extracholecystic benign conditions such as 75% of these are detected on CT [3]. Conversely, the

hepatitis, heart failure, hypoalbuminaemia and acute presence of gallstones alone is not a reliable sign of acute

severe pyelonephritis [1, 3, 5–7]. This review illustrates cholecystitis [1].

the CT features of a spectrum of pathological conditions A thick-walled GB is, however, a non-specific finding

affecting the GB. that may occur in a variety of extrabiliary conditions. The

radiologist should therefore look for associated CT find-

ings suggestive of acute cholecystitis including:

CT signs (1) Transient focal hyperattenuation in the hepatic

parenchyma adjacent to the inflamed GB probably

The thickened GB wall may be of soft tissue density related to hepatic arterial hyperaemia (Figure 5) [9].

(Figure 1) due to mural hypervascularity associated with (2) Indistinct interface of the GB wall and the juxtaposed

the inflammatory process analogous to the hyperaemic liver (Figure 3a), regarded as highly suggestive of

inflamed GB found pathologically in acute cholecystitis [3], acute cholecystitis [3].

or because of diffuse tumoural infiltration. Alternatively, it (3) Pericholecystic stranding, which represents inflam-

may present as a layered, ‘‘sandwich-like’’, mural thicken- matory changes within the fat surrounding the GB

ing (Figures 2, 3a) of an inner enhancing layer of mucosa (Figure 3b). Extensive changes may cause reactive

and an outer enhancing layer of serosa with a hypodense mural thickening and oedema in the adjacent colon

layer of subserosal oedema in between, or as a ‘‘halo’’ (Figure 3c) or duodenum (Figure 3b). Irregular, dis-

of low-attenuation subserosal oedema surrounding the continuous (Figure 6) or absence of GB wall

enhancing mucosa (Figure 4). Occassionally the enhanced enhancement on contrast-enhanced CT as well as

mucosa of the thickened GB wall may mimic a large rim- pericholecystic abscess are specific signs of mural

calcified stone or a GB wall surrounded by pericholecystic necrosis indicating gangrenous cholecystitis, a severe

fluid. These simulations can readily be excluded by sono- form of acute cholecystitis [10].

graphy. On CT, however, the ‘‘halo’’ of oedema can be

distinguished from pericholecystic fluid by demonstrating The presence of gas in the GB wall (Figure 7) represents

small enhancing punctate structures within the oedema- another variant of acute cholecystitis known as emphyse-

tous wall, which is typically global compared with the matous cholecystitis, which is more common in men and

pericystic fluid, which is usually focal [6]. We assume that, in diabetic patients. Gas may also appear within the GB

as on ultrasound, both appearances of ‘‘sandwich’’ or lumen and in the pericholecystic tissue [11]. CT has a

‘‘halo’’ types of GB wall thickening favour a relative significant role in detecting the gas as it mimics calcifica-

benign aetiology [8]. tions or cholesterol deposits on ultrasound.

Acute acalculous cholecystitis is an infrequent but

Received 5 April 2002 and in revised form 6 August 2002, accepted 23 potentially fatal form of acute cholecystitis that usually

September 2002. occurs in critically ill patients [12]. The CT diagnosis is

The British Journal of Radiology, February 2003 137

R Zissin, A Osadchy, M Shapiro-Feinberg and G Gayer

based on either two major criteria, which include GB Trauma

mural thickening, necrosis or gas and pericholecystic

stranding, or on one major and two minor criteria, Isolated penetrating trauma involving the GB is a rare

including distended GB and hyperdense bile (Figure 6) injury. Clinical symptoms may be minimal initially with

[4, 12]. gradual clinical deterioration related to spillage of bile into

the peritoneal cavity. A high clinical index of suspicion is

needed to avoid a diagnostic delay. As abdominal CT is

Extracholecystic inflammatory processes often performed it may elicit findings of mural thickening

and high-density fluid content within the GB representing

Acute hepatitis (Figure 4), peritonitis (Figure 8), acute haemobilia as well as pericholecystic stranding along the

pancreatitis (Figure 9) [7] and acute pyelonephritis tract of the invasion (Figure 14) [14]. Iatrogenic GB

(Figure 10) [5] may cause GB wall thickening. Somer penetration due to hepatic percutaneous biopsy or needle

et al reported increased GB wall thickness in 64% of aspiration and more rarely, following percutaneous

patients with acute pancreatitis in addition to intense nephrostomy or nephrolithotomy is another uncommon

contrast enhancement and pericholecystic oedematous cause of GB perforation [15].

changes [7]. Zissin et al reported signs of venous con-

gestion including small bilateral pleural effusions, thick-

ened interlobular septa in the lungs, congestion of the

hepatic veins and of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and Neoplasms

hepatic periportal tracking, a hypodense thickened GB

wall and ascites in addition to hypodense lesions within Diffuse GB wall thickening secondary to tumour

enlarged kidneys compatible with acute pyelonephritis [5]. infiltration and inflammatory change is a common mani-

festation of advanced GB carcinoma, which is often

detected at a late stage due to lack of early clinical signs [8,

Systemic diseases 16]. Associated findings such as biliary dilatation, invasion

of adjacent structures and liver and nodal metastases, may

Hypoalbuminaemic states (Figure 11) and congestive help in establishing the correct diagnosis and differentiat-

right heart failure (Figure 12) may cause thickening of the ing it from chronic cholecystitis (Figure 15).

GB wall [1, 3]. Additional findings of extravascular volume

overload may be seen, such as pleural or pericardial

effusions, ascites, dependent subcutaneous oedema and

distended IVC. Pulmonary congestion in the lung bases Miscellaneous

may be demonstrated in patients with congestive heart

failure as well. Hypoalbuminaemia in patients on intensive GB wall thickening may be secondary to chronic cholecys-

care units may cause GB wall thickening and can cause titis, adenomyomatosis and polyps [1, 17]. Chronic

confusion with acute acalculous cholecystitis, which occurs cholecystitis may appear on CT with soft-tissue density

most commonly in these patients. CT findings of the wall thickening of, usually, a contracted GB, often around

above-mentioned major or minor criteria of this diagnosis gallstones. A ‘‘porcelain’’ GB is an uncommon form of

may be helpful for distinguishing these conditions (see chronic cholecystitis with coarse mural calcification.

Acalculous cholecystitis). Thickening of the GB wall, either focal or diffuse, on

CT is the common finding of adenomyomatosis.

Proliferation of the subserosal fat and intramural diverti-

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome cula containing small calculi have also been reported [1].

Polypoid lesions of the GB, most commonly cholesterol

Hepatobiliary diseases are frequently encountered polyp, appear on CT as focal mural thickening, usually of

among patients infected with human immunodeficiency less than 10 mm, classified into pedunculated, sessile or

virus. Acalculous cholecystitis is the most common mani-

mass-forming type [17].

festation of GB disease of acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome cholangiopathy, being primarily infectious in

nature. Whilst it is related to various pathogens,

Cryptosporidium is the most common cause of GB wall Summary

thickening in this situation followed by microsporidia such

as Enterocytozoon bieneusi [13]. The thickened GB wall is GB wall thickening may result from a broad spectrum

typically more severe than expected from clinical pre- of pathological conditions, intrinsic as well as extrinsic to

sentation (Figure 13). Other causes of GB wall thickening the biliary tract, and may have different appearances. A

in these patients include neoplastic infiltration of the GB correct diagnosis is usually established after a correlation

wall by Kaposi’s sarcoma and primary lymphoma. of imaging findings, laboratory data and clinical history.

138 The British Journal of Radiology, February 2003

Pictorial review: CT of a thickened-wall gall bladder

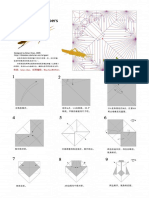

Figure 1. A 75-year-old woman with acute cholecystitis. Con- Figure 2. An 81-year-old with acute cholecystitis. Contrast

trast enhanced CT shows a distended gallbladder with mural enhanced CT shows a ‘‘sandwich-like’’ thickening of the gall-

thickening of soft tissue density, pericholecystic stranding bladder wall, representing hypodense submucosal oedema sur-

(arrowhead) and reactive thickening of the adjacent colonic rounded by an inner layer of enhancing mucosa (arrow) and

wall at the hepatic flexure (arrow). an outer layer of enhancing serosa (arrowhead).

(a) (b)

Figure 3. A 76-year-old woman with acute cholecystitis. (a)

Contrast enhanced CT shows a distended gallbladder (GB)

with ‘‘sandwich-like’’ mural thickening, pericholecystic strand-

ing of inflammatory changes and indistinct interface between

the GB and the adjacent liver (arrows). (b) 2 cm caudally to

(a), marked pericholecystic inflammatory changes (arrowheads)

are seen with reactive thickening of the adjacent duodenum (D).

(c) 2 cm caudally to (b), reactive mural thickening of the juxta-

posed hepatic flexure (C) is demonstrated.

(c)

The British Journal of Radiology, February 2003 139

R Zissin, A Osadchy, M Shapiro-Feinberg and G Gayer

Figure 4. A 28-year-old man with drug-induced hepatitis. Figure 5. A 71-year-old man with acute cholecystitis. Contrast-

Contrast-enhanced CT shows a ‘‘halo-like’’ thickening of the enhanced CT shows a distended thickened-wall gallbladder

gallbladder wall, representing the enhancing mucosa (arrow- with a fluid–fluid level of high-attenuation bile (arrow). Note

head) surrounded by subserosal oedema. the focal increased attenuation within the adjacent liver par-

enchyma (arrowheads) representing reactive hepatic arterial

hyperaemia.

Figure 6. A 85-year-old woman with acute gangrenous chole-

cystitis. Contrast enhanced CT shows a distended gallbladder Figure 7. A 74-year-old man with acute emphysematous chole-

with gas-containing gallstones. Halo-like mural thickening with cystitis. CT shows gas within a thickened gallbladder wall (arrows)

interrupted mucosa (curved arrow) is seen, compatible with containing a large gallstone (arrowhead). Note the pericholecystic

necrotizing, gangrenous cholecystitis. dissection of the gas (G).

140 The British Journal of Radiology, February 2003

Pictorial review: CT of a thickened-wall gall bladder

Figure 8. A 93-year-old woman 10 days after surgery for per- Figure 9. A 36-year-old woman with acute pancreatitis. Contrast

forated duodenal ulcer presented with fever and pus discharge enhanced CT shows a thickened gallbladder wall with enhan-

through operative sutures. Contrast enhanced CT shows gas cing, thickened mucosa (arrowhead) and subserosal oedema.

bubbles and extravasation of the orally ingested contrast Note enlargement of the pancreatic head and the peripancreatic

medium (black arrow) reaching the skin (white arrow), compa- fluid (arrow).

tible with leak and cutaneous fistula. Reactive ‘‘sandwich-like’’

thickening of the gallbladder wall is seen.

Figure 10. A 57-year-old woman with acute pyelonephritis. Figure 11. A 73-year-old man with liver cirrhosis. Contrast

Contrast enhanced CT at the mid-abdomen shows a halo-like enhanced CT shows thickening of the gallbladder wall of soft-

thickening of the gallbladder wall, ascitic fluid and hypodense tissue density (arrowhead), ascites, splenomegaly and atrophic

lesions within the enlarged right kidney (arrowheads). liver with lobular borders.

The British Journal of Radiology, February 2003 141

R Zissin, A Osadchy, M Shapiro-Feinberg and G Gayer

(a) (b)

Figure 12. A 79-year-old woman with right-sided heart failure. (a) Contrast enhanced CT at the level of the upper abdomen shows

‘‘geographic’’ appearance of the congested liver and bilateral pleural effusions. (b) At a lower level, a thickened-wall gallbladder with

enhancing mucosa (arrows) subserosal oedema is seen as well as ascitic fluid.

Figure 14. A 25-year-old woman presented with fever and

abdominal tenderness 2 days following penetrating trauma in

the right upper quadrant (RUQ). Contrast-enhanced CT shows

Figure 13. A 31-year-old HIV positive man presented with gallbladder (GB) wall thickening (asterisk) with intraluminal

jaundice and abnormal liver function tests. Contrast enhanced bile-blood level (arrowhead), infiltration within the posterior

CT shows splenomegaly a distended, thick-walled gallbladder pericholecystic tissue (black arrow) and the RUQ subcutaneous

(asterisk), which was further confirmed at surgery. Histology defect (white arrow) indicating the stab wound. At surgery two

revealed acute and chronic inflammatory changes with a posi- lacerations were found within the anterior and posterior aspect

tive immunoperoxidase stain for Cytomegalovirus. of the GB with mild biliary peritonitis.

142 The British Journal of Radiology, February 2003

Pictorial review: CT of a thickened-wall gall bladder

5. Zissin R, Kots E, Rachmani R, Hadari R, Shapiro-Feinberg

M. Hepatic periportal tracking associated with severe acute

pyelonephritis. Abdom Imaging 2000;25:251–4.

6. Goldstein RB, Wing VW, Laing FC, Jeffrey RB. Computed

Tomography of thick-walled gallbladder mimicking peri-

cholecystic fluid. JCAT 1986;10:55–6.

7. Somer K, Kivisaari L, Standertskjold-Nordenstam CG,

Kalima TV. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of

the gallbladder in acute pancreatitis. Gastrointest Radiol

1984;9:31–4.

8. Wibbenmeyer LA, Sharafuddin MJA, Wolverson MK,

Heiberg EV, Wade TP, Shields JB. Sonographic diagnosis

of unsuspected gallbladder cancer: imaging findings in

comparison with benign gallbladder conditions. AJR 1995;

165:1169–74.

9. Yamashita K, Jin MJ, Hirose Y, Morikawa M, Sumioka H,

Itoh K, et al. CT findings of transient focal increased

attenuation of the liver adjacent to the gallbladder in acute

cholecystitis. AJR 1995;164:343–6.

Figure 15. A 67-year-old woman with gallbladder (GB) carci- 10. Bennett GL, Rusinek H, Lisi V, Israel GM, Krinsky GA,

noma. Contrast enhanced CT shows multiple metastatses Slywotzky CM, et al. CT findings in acute gangrenous

(black arrows) within the liver and a thick-walled GB with irre- cholecystitis. AJR 2002;178:275–81.

gular mucosal (white arrows) thickening and polypoid masses 11. Gill KS, Chapman AH, Weston MJ. The changing face of

(arrowhead) of soft-tissue density within the subserosal oedema emphysematous cholecystitis. Br J Radiol 1997;70:986–91.

(asterisk). 12. Jacobs JE, Birnbaum BA. Abdominal computed tomography

in intensive care unit patients. Semin Roentgenol 1997;

32:128–41.

References 13. Wicox CM, Monkemuller KE. Hepatobiliary disease in

patients with AIDS: focus on AIDS cholangiopathy and

1. Herbener TE. The gallbladder and biliary tract. In: Haaga gallbladder disease. Dig Dis 1998;16:205–13.

JR, Lanzieri CF, Sartoris DJ, Zerhouni EA, editors. 14. Sabetai MM, Velmahos GC, Schreier DZ. Preoperative

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging diagnosis of isolated penetrating gallbladder injury in an

of Whole Body, Edn 3, Vol. 2. St Louis, MO: Mosby, asymptomatic patient: the role of hepato-iminodiacetic acid

1994:978–1036. scan as the definitive diagnostic test. Am Surg 1998;64:772–4.

2. Fidler J, Paulson EK, Layfield L. CT evaluation of acute 15. Lublin M, Danforth DN. Iatrogenic gallbladder perforation:

cholecystitis: findings and usefulness in diagnosis. AJR conservative management by percutaneous drainage and

1996;166:1085–8. cholecystostomy. Am Surg 2001;67:760–3.

3. Paulson EK. Acute cholecystitis: CT findings. Seminars in 16. Rooholamini SA, Tehrani NS, Razavi MK, Au AH, Hansen

US, CT, and MRI. 2000;21:56–63. GC, Ostrzega N, Verma RC. Imaging of gallbladder

4. Mirvis SE, Vainright JR, Nelson AW, Johnson GS, Shorr R, carcinoma. Radiographics 1994;14:291–306.

Rodriguez A, et al. The diagnosis of acute acalculous 17. Furukawa H, Takayasu K, Mukai K, Inoue K, Kyokane T,

cholecystitis: a comparison of sonography, scintigraphy and Shimada K, et al. CT evaluation of small polypoid lesion of

CT. AJR 1986;147:1171–5. the gallbladder. Hepatogastroenterology 1995;42:800–10.

The British Journal of Radiology, February 2003 143

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- SOP Receiving and Storage of Raw MaterialsDocumento2 pagineSOP Receiving and Storage of Raw MaterialsBadethdeth1290% (10)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- CORE4 ABS Month 2 Workouts PDFDocumento9 pagineCORE4 ABS Month 2 Workouts PDFkamehouse100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Brian Chan-Locust PDFDocumento10 pagineBrian Chan-Locust PDFdrrahulsshindeNessuna valutazione finora

- Quarterly Oru Folding Diagrams Vol 1Documento199 pagineQuarterly Oru Folding Diagrams Vol 1drrahulsshinde95% (20)

- Quarterly Oru Folding Diagrams - Vol.2Documento186 pagineQuarterly Oru Folding Diagrams - Vol.2drrahulsshinde89% (19)

- Boracay Rehabilitation: A Case StudyDocumento9 pagineBoracay Rehabilitation: A Case StudyHib Atty TalaNessuna valutazione finora

- 13fk10 Hav Igg-Igm (D) Ins (En) CeDocumento2 pagine13fk10 Hav Igg-Igm (D) Ins (En) CeCrcrjhjh RcrcjhjhNessuna valutazione finora

- 2019 SEATTLE CHILDREN'S Hospital. Healthcare-Professionals:clinical-Standard-Work-Asthma - PathwayDocumento41 pagine2019 SEATTLE CHILDREN'S Hospital. Healthcare-Professionals:clinical-Standard-Work-Asthma - PathwayVladimir Basurto100% (1)

- Kraniotomi DekompresiDocumento17 pagineKraniotomi DekompresianamselNessuna valutazione finora

- Ultrasound Spectrum in Intraductal Papillary Neoplasms of BreastDocumento7 pagineUltrasound Spectrum in Intraductal Papillary Neoplasms of BreastdrrahulsshindeNessuna valutazione finora

- Tubeless Hypotonic DuodenographyDocumento12 pagineTubeless Hypotonic DuodenographydrrahulsshindeNessuna valutazione finora

- Surgical Anatomy PF PNSDocumento11 pagineSurgical Anatomy PF PNSdrrahulsshindeNessuna valutazione finora

- Frontal Sinus Drainage Pathway PDFDocumento9 pagineFrontal Sinus Drainage Pathway PDFdrrahulsshindeNessuna valutazione finora

- Mobile Health Clinic InitiativeDocumento47 pagineMobile Health Clinic InitiativededdyNessuna valutazione finora

- Synopsis - Anu Varghese and Dr. M H Salim, 2015 - Handloom Industry in Kerala A Study of The Problems and ChallengesDocumento8 pagineSynopsis - Anu Varghese and Dr. M H Salim, 2015 - Handloom Industry in Kerala A Study of The Problems and ChallengesNandhini IshvariyaNessuna valutazione finora

- PIIS0261561422000668 Micronitrientes: RequerimientosDocumento70 paginePIIS0261561422000668 Micronitrientes: Requerimientossulemi castañonNessuna valutazione finora

- Statistical EstimationDocumento37 pagineStatistical EstimationAmanuel MaruNessuna valutazione finora

- Two Dimensional and M-Mode Echocardiography - BoonDocumento112 pagineTwo Dimensional and M-Mode Echocardiography - BoonRobles RobertoNessuna valutazione finora

- Gavi - 2015 Country TA RFIDocumento20 pagineGavi - 2015 Country TA RFIDeepakSinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 5 Job and OccupationDocumento3 pagineUnit 5 Job and OccupationAstriPrayitnoNessuna valutazione finora

- Ijtk 9 (1) 184-190 PDFDocumento7 pagineIjtk 9 (1) 184-190 PDFKumar ChaituNessuna valutazione finora

- (Norma) Guia Fda CovidDocumento14 pagine(Norma) Guia Fda CovidJhovanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lumbar Interbody Fusions 1St Edition Edition Sunil Manjila Full ChapterDocumento67 pagineLumbar Interbody Fusions 1St Edition Edition Sunil Manjila Full Chapterlaurence.williams167100% (6)

- SDS N 7330 NorwayDocumento15 pagineSDS N 7330 NorwaytimbulNessuna valutazione finora

- Radiation Protection Rules 1971Documento10 pagineRadiation Protection Rules 1971KomalNessuna valutazione finora

- Ozone As A Disinfecting Agent in The Reuse of WastewaterDocumento9 pagineOzone As A Disinfecting Agent in The Reuse of WastewaterJoy Das MahapatraNessuna valutazione finora

- BM Waste Color CodingDocumento23 pagineBM Waste Color Codingpriyankamote100% (1)

- 9401-Article Text-17650-1-10-20200718Documento5 pagine9401-Article Text-17650-1-10-20200718agail balanagNessuna valutazione finora

- Excerpts From IEEE Standard 510-1983Documento3 pagineExcerpts From IEEE Standard 510-1983VitalyNessuna valutazione finora

- Study On Consumer Behavior For Pest Control Management Services in LucknowDocumento45 pagineStudy On Consumer Behavior For Pest Control Management Services in LucknowavnishNessuna valutazione finora

- Lights and ShadowsDocumento5 pagineLights and Shadowsweeeeee1193Nessuna valutazione finora

- ResumeDocumento2 pagineResumeapi-281248740Nessuna valutazione finora

- BB - Self AuditDocumento18 pagineBB - Self AuditFe Rackle Pisco JamerNessuna valutazione finora

- First Aid 10Documento16 pagineFirst Aid 10Oswaldo TorresNessuna valutazione finora

- Fermented Fruit JuiceDocumento4 pagineFermented Fruit JuiceEduardson JustoNessuna valutazione finora

- WASH in CampsDocumento13 pagineWASH in CampsMohammed AlfandiNessuna valutazione finora

- 16-23 July 2011Documento16 pagine16-23 July 2011pratidinNessuna valutazione finora