Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome - A Common Reproductive Syndrome With Long-Term Metabolic Consequences

Caricato da

KopeDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome - A Common Reproductive Syndrome With Long-Term Metabolic Consequences

Caricato da

KopeCopyright:

Formati disponibili

CME Review Article

Polycystic ovary syndrome: a common

reproductive syndrome with long-term

metabolic consequences

Tiffany TL Yau, Noel YH Ng, LP Cheung, Ronald CW Ma *

ABSTRACT focus on the specific needs of the individual, and

may change according to different stages of the life

Polycystic ovary syndrome is the most common

course. In view of the clinical manifestations of the

endocrine disorder among women of reproductive

condition, there is recent debate about whether

age. Although traditionally viewed as a reproductive

the current name is misleading, and whether

disorder, there is increasing appreciation that it

the condition should be renamed as metabolic

is associated with significantly increased risk of

reproductive syndrome.

cardiometabolic disorders. Women with polycystic

ovary syndrome may present to clinicians via a

variety of different routes and symptoms. Although

Hong Kong Med J 2017;23:622–34

the impact on reproduction predominates during the

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj176308

reproductive years, the increased cardiometabolic

problems are likely to become more important at 1

TTL Yau #, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)

later stages of the life course. Women with polycystic 1

NYH Ng #, BSc, MRes

ovary syndrome have an approximately 2- to 5-fold 2

LP Cheung, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)

increased risk of dysglycaemia or type 2 diabetes, and 1,3

RCW Ma *, FRCP, FHKAM (Medicine)

hence regular screening with oral glucose tolerance #

TT Yau and NY Ng have equal contribution in this study.

test is warranted. Although the diagnostic criteria

for polycystic ovary syndrome are still evolving and 1

Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of

are undergoing revision, the diagnosis is increasingly Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

focused on the presence of hyperandrogenism, with 2

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of

Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

the significance of polycystic ovarian morphology 3

Hong Kong Institute of Diabetes and Obesity, The Chinese University of

This article was in the absence of associated hyperandrogenism or Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

published on 24 Nov anovulation remaining uncertain. The management

2017 at www.hkmj.org. of women with polycystic ovary syndrome should * Corresponding author: rcwma@cuhk.edu.hk

Introduction experienced a diagnostic delay in excess of 2 years.5

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) was first Diagnosis of polycystic ovary

described by Stein and Leventhal in 1935,1 when

they noted an association between the presence of

syndrome: historical aspects and

bilateral polycystic ovaries and signs of amenorrhoea, evolution of diagnostic criteria

oligomenorrhoea, hirsutism, and obesity. It is now Polycystic ovary syndrome is considered to be

recognised as one of the most common endocrine a heterogeneous disorder with multifactorial

disorders of women, affecting between 6% and 12% cause. The principal features of PCOS include

of women overall.2 A study in southern Chinese hyperandrogenism, oligomenorrhoea, and/or

reported a prevalence of 2.2% among women of polycystic ovaries. There have been several proposed

reproductive age.3 The prevalence can be as high diagnostic criteria for PCOS as described in Table

as 70% to 80% in women with oligoamenorrhoea 1.6-9 All criteria require exclusion of other disorders

and 60% to 70% in women with anovulatory that may mimic the clinical features of PCOS, such

infertility. Women with PCOS have an increased as thyroid dysfunction, hyperprolactinaemia, non-

risk of gynaecological, reproductive, medical and classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), and

sleep problems, and hence are at risk of increased Cushing’s syndrome.

morbidities across the life course (Fig 1).4 Despite The prevalence of PCOS depends on the

being a common condition, however, the presenting diagnostic criteria used to define the disorder. To

features of PCOS are often not recognised, resulting date, the prevalence of PCOS has been determined

in a delay in diagnosis. In a recent international primarily using the National Institutes of Health

survey, approximately half of the women with PCOS 1990 criteria. A summary report from the National

consulted three or more health care providers before Institutes of Health Evidence-based Methodology

the diagnosis was made, and more than one third Workshop on PCOS in December 2012 concluded

622 Hong Kong Med J ⎥ Volume 23 Number 6 ⎥ December 2017 ⎥ www.hkmj.org

# Polycystic ovary syndrome #

that the Rotterdam criteria should be adopted for

now because it is the most inclusive.10 Using the 多囊卵巢綜合症:常見的生殖內分泌

Rotterdam criteria, many patients can be diagnosed

based on the history and physical examination (eg 代謝異常疾病

a history of irregular menses, and clinical signs of 丘芷苓、吳逸晞、張麗冰、馬青雲

hyperandrogenism). The panel also suggested that 多囊卵巢綜合症是生育年齡婦女中最常見的內分泌紊亂疾病。雖然傳

the disorder should be renamed to more adequately 統上被視為一種生殖障礙,但人們越發意識到此症可能會增加心臟代

reflect the complex metabolic, hypothalamic, 謝異常的風險。多囊卵巢綜合症患者可能會出現不同種類的症狀。雖

pituitary, ovarian, and adrenal interactions that 然此症會在生育期內影響患者懷孕的機會,事實上它在往後的日子增

characterise the syndrome. A previous local study 加患者心臟代謝的問題更不容忽視。多囊卵巢綜合症患者患有血糖異

by Lam et al11 comparing the different diagnostic 常或II型糖尿病的風險增加約2至5倍,因此有必要定期進行口服葡萄

criteria in Hong Kong Chinese women concluded 糖耐量測試的檢測。雖然多囊卵巢綜合症的診斷標準仍在發展階段,

that the Rotterdam criteria are generally applicable 亦不斷進行修訂,但診斷越見集中在雄激素過多的層面。在沒有雄激

to our population. Nevertheless, recent discussion 素過多或持續無排卵的情況下,多形性卵巢形態是否重要仍具爭論。

has centred on the importance of hyperandrogenism, 治理多囊卵巢綜合症的婦女應根據個別患者的需要,也可能會隨着患

and emerging evidence suggests that women with 者的年齡而改變。鑑於病情的臨床表現,最近有關此症存在爭辯,包

radiological evidence of polycystic ovaries, but 括其名稱是否誤導,以及應否改名為代謝性生殖綜合症。

no other clinical features of PCOS, represent a

population generally of lower risk who are distinct

from other women with PCOS who fulfil current

diagnostic criteria.12

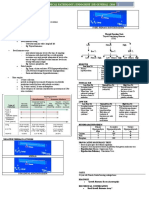

Prenatal Childhood Adolescence Reproductive Postmenopausal

Pathogenesis

Menstrual

To date, the pathophysiology of PCOS remains Premature irregularities

adrenarche

unclear; yet, substantial evidence suggests it is

Infertility

a multifactorial condition, where interactions Reproductive Endometrial

between endocrine, metabolic, genetic, and cancer

environmental factors intrinsic to each other act

in consonance towards a common result (Fig 2).13,14 Acne

Endocrine

Also, the heterogeneity of PCOS further reinforces Hirsutism

its multifactorial nature. Although familial

Impaired glucose tolerance

segregation of cases suggests a genetic component

in this syndrome, most of the susceptibility genes Gestational diabetes, type 2 diabetes

and single-nucleotide polymorphisms remain to Cardio- Dyslipidaemia

metabolic

be discovered.15,16 Among its diverse phenotypes, Hypertension

hyperandrogenism and ovarian dysfunction are Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

recognised as the two main features of PCOS.6,16 Cardiovascular

Hyperandrogenism in PCOS is recognised as the disease

excessive androgen biosynthesis, use, and meta- FIG 1. Impacts of polycystic ovary syndrome on reproductive, endocrine, and

bolism. When the ovaries are stimulated to produce cardiometabolic outcome across the life course

excessive amounts of androgen, an accumulation of

numerous follicles or cysts can be observed in the

ovary. Insulin resistance is also a major cause of

hyperandrogenism in PCOS, through stimulating the

(LH) can lead to an increase in androgen production

secretion of ovarian androgen and inhibiting hepatic

by the ovarian thecal cells. This is thought to be due to

sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) production.17

increased gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)

Approximately 80% to 85% of women with clinicalpulse frequency, resulting in increased frequency

hyperandrogenism have PCOS.8,18 Women with and pulsatile secretion of LH, and increased levels

PCOS and hyperandrogenism may experience excessof LH relative to follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

hair growth, acne, and/or abnormal folliculogenesis.

in the circulation.14,19,20 There also appears to be

Three major pathophysiological pathways have been

resistance to the negative feedback by progesterone

described, but they are not mutually exclusive. They

to the GnRH pulse generator, which is often present

are ovulatory dysfunction, disordered gonadotropin

by puberty. The increased LH/FSH ratio, along with

release, and insulin resistance. some ovarian resistance to FSH, results in excess

production of androgens from thecal cells in ovarian

Disordered gonadotropin release and excess follicles, leading to impaired follicular development,

androgen release and reduced inhibition of the GnRH pulse generator

In PCOS, hypersecretion of luteinising hormone by progesterone, thereby setting up a vicious cycle

Hong Kong Med J ⎥ Volume 23 Number 6 ⎥ December 2017 ⎥ www.hkmj.org 623

# Yau et al #

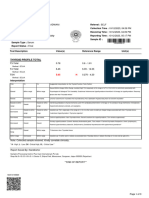

TABLE 1. Summary of proposed diagnostic criteria for PCOS in adults6-9 *

Criteria National Rotterdam Androgen Excess

Institutes of (2003)— and PCOS

Health (1990)6 diagnosis Society (2009)—

established if 2 diagnosis requires

out of 3 criteria hyperandrogenism

are met7 with 1 of 2

remaining criteria8

Hyperandrogenism Clinical hyperandrogenism + +/- +

• Acne or hirsutism or androgenic alopecia

and/or

Biochemical hyperandrogenism

• Elevated serum androgen level (total testosterone or

bioavailable testosterone or free testosterone)†

Oligo-anovulation • ≤8 Menstrual cycles per year, or frequent bleeding at intervals + +/- +/-

<21 days, or infrequent bleeding at intervals >35 days

• Mid-luteal progesterone documenting anovulation

Polycystic ovary • >12 Follicles of 2-9 mm in diameter in at least one ovary Not required +/- +/-

(without a cyst or dominant follicle), and/or

• Ovarian volume >10 mL

Abbreviation: PCOS = polycystic ovary syndrome

* Legend: + indicates an essential criterion for diagnosis; +/- indicates clinical features that are one of the criteria which may need to be present for the

diagnosis to be established

† Given the variability in testosterone level and the suboptimal standardisation of assays, it is difficult to define an absolute level that is diagnostic of PCOS

or other causes of hyperandrogenism, and the Task Force recommends familiarity with cut-offs of local assays9

Insulin resistance

Altered caused by:

Hypothalamus

Hypothalamic neurons adipocytokines • genetic

• environment

Hypothalamus

• obesity

Inflowing

blood

Portal

blood

Increased GnRH Adipose • adipocyte

Anterior

vessels

pulse frequency tissue dysfunction

pituitary

Pituitary Posterior

pituitary

Pancreas

FSH LH Progesterone

Hyperinsulinaemia

Liver

Hyperandrogenism ↓ SHBG

↑ LH/FSH ratio

↑ TG

↑ DHEAS production

↑ IGF-1 ↓ IGFBP-1 ↑ Cholesterol

Adrenal

gland

With ↑ LH

Theca cell Follicular arrest

leading to PCOM

Androgen

Granulosa cell

Ovary

Oestrogen

FIG 2. Pathophysiology of polycystic ovary syndrome

Abbreviations: DHEAS = dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate; FSH = follicle-stimulating hormone; GnRH = gonadotropin-releasing hormone; IGF-1 = insulin-like

growth factor 1; IGFBP-1 = insulin-like growth factor–binding protein-1; LH = luteinising hormone; PCOM = polycystic ovarian morphology; SHBG = sex

hormone–binding globulin; TG = triglycerides

624 Hong Kong Med J ⎥ Volume 23 Number 6 ⎥ December 2017 ⎥ www.hkmj.org

# Polycystic ovary syndrome #

that exacerbates the hypersecretion of LH, and among lean patients with PCOS, but this is further

ovulatory dysfunction.14,19,20 exacerbated in the presence of obesity.39,40

A stepwise increase in the prevalence of

Ovulatory dysfunction glucose intolerance with increasing body mass index

(BMI) has been described in cross-sectional studies

Unlike the ovarian follicular development in healthy performed in women with this disorder.41 Although

women, in PCOS cases, follicle growth is disrupted most women with PCOS have normal insulin

due to ovarian hyperandrogenism, hyperinsulinaemia secretory responsiveness, studies have suggested

from insulin resistance, and intra-ovarian paracrine that PCOS women, particularly those with a family

signalling. Hyperinsulinaemia further impairs follicle history of type 2 diabetes (T2D), have impaired

growth by amplifying LH-stimulated and insulin- β-cell function or a subnormal disposition index (an

like growth factor 1 (IGF-1)–stimulated androgen index of β-cell function that takes insulin resistance

production.21-24 Hyperinsulinaemia also elevates into account).16,42,43

serum free testosterone levels through decreased

hepatic SHBG production, and enhances serum Adipose dysfunction

IGF-1 bioactivity through suppression of IGF-binding

Although the full molecular mechanisms underlying

protein production.25 Insulin excess also promotes

insulin resistance in PCOS remain unclear, primary

premature follicle luteinisation through enhanced

defects in insulin-medicated glucose transport,44

FSH-induced granulosa cell differentiation, which

GLUT4 production,45 and insulin or adrenergic

arrests granulosa cell proliferation and subsequent

regulated lipolysis46 in adipocytes (and sometimes

follicle growth.26 Finally, overproduction of anti-

in myocytes and fibroblasts) have been reported.

Müllerian hormone (AMH)27-29 by the granulosa cells

Insulin resistance in PCOS contributes to the

of ovarian follicles in PCOS appears to antagonise

dysfunctional adipogenesis to some degree from an

FSH action in small PCOS follicles. The relatively

30

impaired capacity of regional adipose tissue storage

lower FSH levels contribute to arrested follicular

to properly expand with increased dietary caloric

development in the ovary, leading to amenorrhoea,

intake.47-49 Adipose tissue secretes numerous factors

anovulation, and polycystic morphology. 8,16

to regulate metabolic function, appetite, neural

activity, and digestion. This tissue is also heavily

Insulin resistance infiltrated by macrophages, and a crosstalk exists

In PCOS cases, there is an increased level of between adipocytes, macrophages, and pluripotent

bioavailable androgens that leads to increased insulin cells for complex paracrine interactions. It is known

resistance in peripheral tissues (mostly in the skeletal that dysregulation of adipokine production, such

muscle).31 Insulin resistance causes compensatory as adiponectin, by macrophage-secreted cytokines

hyperinsulinaemia and might contribute to in PCOS facilitates the development of insulin

hyperandrogenism and gonadotropin aberrations resistance.50 Other adipokines including leptin,

through several mechanisms. Insulin may act retinol-binding protein 4, and visfatin have also

directly in the hypothalamus, the pituitary or both been implicated.51 Improved understanding of the

and thereby contribute to abnormal gonadotropin underlying mechanisms that govern adipose tissue

levels. By facilitating the stimulatory role of LH, dysfunction and insulin resistance in PCOS would be

hyperinsulinaemia leads to further increase in beneficial in the identification of novel therapeutic

ovarian androgen production in theca calls.32 High targets for PCOS and other related disorders.16

insulin can also serve as a co-factor to stimulate

adrenocorticotropic hormone–mediated androgen Intrauterine environment

production in the adrenal glands.33 Moreover, an In humans, rhesus monkeys and sheep, inappropriate

insulin-induced decrease in the production of SHBG testosterone exposure during fetal life alters the

in the liver increases the amount of free bioavailable developmental trajectory of the female leading

androgens.34 to PCOS-like phenotypes, such as phenotypic

Most women with PCOS, particularly those masculinisation; reproductive, neuroendocrine,

who are overweight or obese, do in fact have insulin ovarian disruptions; and hyperinsulinaemia.52 In

resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinaemia,35,36 a human study, it has been shown that there is an

partly attributable to an intrinsic insulin resistance increased prevalence of PCOS in women with classic

mechanism.36-38 CAH and congenital adrenal virilising tumours.53

Using the homeostasis model assessment, 50% In one human study, higher testosterone levels

to 70% of women with PCOS demonstrate insulin compared with those usually observed in normal

resistance. Using the gold standard technique females were found in the umbilical vein of female

of euglycaemic hyperinsulinaemic clamp, it was infants born to mothers with PCOS54; yet, another

found that PCOS exhibits insulin resistance that prospective study that investigated the relationship

is independent of obesity, and is present even between prenatal androgen exposure and the

Hong Kong Med J ⎥ Volume 23 Number 6 ⎥ December 2017 ⎥ www.hkmj.org 625

# Yau et al #

development of PCOS in female adolescence did not Clinical features and

confirm any association between these variables.55

Excess fetal exposure to maternal androgens

co-morbidities

is thought to contribute to induction of the PCOS Gynaecological and reproductive

phenotype in offspring/children. Nonetheless, more dysfunction

clinical studies are needed to confirm the role of Menstrual dysfunction is common and is

intrauterine androgen exposure on human fetal characterised by oligomenorrhoea and, less often,

development. amenorrhoea. Nonetheless, menstrual problems are

frequently neglected and anovulatory infertility is

Recent insights from genetic studies frequently the initial complaint for which the patient

Polycystic ovary syndrome has a high heritability seeks medical advice. Women with PCOS have an

of approximately 80%. Although a large number of increased risk of miscarriage, gestational diabetes,

candidate gene studies have been conducted, no pre-eclampsia, and preterm labour.58-60 A meta-

genetic variants have been found to be consistently analysis highlighted that the risks of gestational

associated with PCOS. Recent hypothesis-free diabetes, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and pre-

genome-wide association studies using high-density eclampsia are approximately 3-fold, whereas the risk

genotyping arrays that systematically investigate for preterm labour is approximately 2-fold among

common variants across the genome have identified women with PCOS.58 The reasons for the adverse

several genetic loci to be significantly associated pregnancy outcomes are unclear, but hypersecretion

with PCOS (Table 2).56 These have shed light on of LH, hyperandrogenaemia and hyperinsulinaemia

the important role of the gonadotropin axis in the have all been postulated. Due to anovulatory

pathogenesis of PCOS, as well as several other dysfunction and consequent long-term unopposed

novel pathways, including epidermal growth factor oestrogen stimulation, PCOS patients are at

signalling. Interestingly, genetic studies have increased risk of endometrial cancer.61,62 Nonetheless,

revealed a significant overlap of findings when there is currently no consensus to support routine

different diagnostic criteria of PCOS have been biopsy or ultrasound of the endometrium for endo-

applied, highlighting greater homogeneity than metrial hyperplasia or cancer screening in asymp-

previously appreciated.16,56,57 tomatic women due its poor diagnostic accuracy.63

TABLE 2. Genetic loci associated with polycystic ovary syndrome discovered in genome-wide association studies56

Chromosome Nearest gene GWAS top SNP Odds ratio P value Discovery population Replicated population(s)

2p16.3 LHCGR rs13405728 1.41 7.55 x 10-21 Chinese Europeans, Indians

2p16.3 FSHR rs2268361 1.15 9.89 x 10 -13

Chinese Europeans, Arabs, Chinese

2p21 THADA rs13429458 1.49 1.73 x 10 -23

Chinese Europeans, Chinese

2q34 ERBB4 rs1351592 1.18 1.2 x 10-12 Chinese -

5q31.1 RAD50 rs13164856 1.13 3.5 x 10 -9

Chinese -

8p32.1 GATA4 rs804279 1.35 8.0 x 10-10 Chinese -

9q33.3 DENND1A rs2479106 1.34 8.12 x 10 -19

Chinese Europeans

9q22.32 C9orf3 rs4385527 1.19 5.87 x 10 -9

Chinese Chinese, Europeans

rs3802457 1.30 5.28 x 10-14 Chinese -

11p14.1 FSHB rs11031006 1.16 1.9 x 10 -8

European Europeans, Chinese

11q22.1 YAP1 rs1894116 1.27 1.08 x 10-22 Chinese Europeans, Chinese

rs11225154 1.22 7.6 x 10-11 European Chinese

12q14.3 HMGA2 rs2272046 1.43 1.95 x 10-21 Chinese Europeans

12q13.2 RAB5B/SUOX rs705702 1.27 8.64 x 10-26 Chinese Europeans

12q21.2 KRR1 rs1275468 1.13 1.9 x 10 -8

Europeans -

16q12.1 TOX3 rS4784165 1.15 3.64 x 10-11 Chinese Europeans

19p13.3 INSR rs2059807 1.14 1.09 x 10-8 Chinese Europeans

20q13.2 SUMO1P1 rs6022786 1.13 1.83 x 10-9 Chinese -

Abbreviations: GWAS = genome-wide association study; SNP = single-nucleotide polymorphism

626 Hong Kong Med J ⎥ Volume 23 Number 6 ⎥ December 2017 ⎥ www.hkmj.org

# Polycystic ovary syndrome #

Endocrine dysfunction 2-fold increase in risk of cardiovascular diseases.72 A

Women with PCOS have varying degrees and cross-sectional study evaluated the cardiometabolic

manifestations of androgen excess. Clinical signs of risk factors in 295 Hong Kong Chinese women with

hyperandrogenism include acne, hirsutism, male- PCOS with a mean age of 30 years.68 It found that

pattern hair loss, and/or elevated serum androgen the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in this cohort

concentrations. Hirsutism is the most common was 24.9% despite their relatively young age, a 5-fold

symptom of hyperandrogenism, affecting up to 70% increase in risk compared with women without

of women with PCOS. It is commonly noted on the PCOS even after controlling for age and BMI.68 In

upper lip, chin, periareolar area, in the mid-sternum, another study involving 170 Asian women with

and along the linea alba of the lower abdomen. There PCOS, metabolic syndrome as defined according to

is substantial ethnic variation in hirsutism where the International Diabetes Federation criteria was

Asian women with PCOS have a lesser degree of present in 35.3% of the subjects.73

hirsutism.8 Signs of more severe androgen excess— The prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver

such as deepening of the voice, breast atrophy, disease (including non-alcoholic steatohepatitis),

and clitoromegaly—occur rarely and suggest the and obstructive sleep apnoea is also increased in

possibility of ovarian hyperthecosis or an androgen- women with PCOS. Even after controlling for BMI,

secreting tumour. women with PCOS are still 30 times more likely to

have sleep-disordered breathing and 9 times more

likely than controls to have daytime sleepiness.74,75

Metabolic dysfunction and cardiovascular The presence of obesity, insulin resistance,

risks impaired glucose tolerance (or T2D), and

Polycystic ovary syndrome is associated with dyslipidaemia may predispose women with PCOS to

cardiovascular risk factors, including obesity, coronary heart disease. An excess risk of coronary

hypertension, glucose intolerance, dyslipidaemia, heart disease or stroke in women with PCOS,

and obstructive sleep apnoea.64 The high prevalence however, is not well established due to the lack of

of metabolic disturbances and the consequent long-term prospective studies. Available studies

increase in the long-term risk of T2D indicate are mostly too small to detect differences in event

that PCOS should be considered a general health rates, and none have shown an evident increase

problem rather than just a reproductive syndrome. in cardiovascular events.76-79 Therefore, the focus

Most investigators found that at least one half of has been on risk factors of cardiovascular disease

PCOS women are obese.8 The prevalence of obesity although these may not necessarily equate with

in PCOS varies widely with the population studied, events or mortality. Studies have found that women

similar to the wide variability in prevalence of obesity with PCOS have an increased carotid intima media

in the general population. thickness and coronary artery calcification, the

Insulin resistance occurs in 60% to 80% of two major surrogate markers for atherosclerotic

women with PCOS, and 95% of obese women cardiovascular disease.80-82 Serum concentrations

with PCOS. The risk of T2D is increased in PCOS, of C-reactive protein, a biochemical predictor of

particularly in women with a first-degree relative cardiovascular disease, also appear to be commonly

with T2D.65 In a systematic review, it was estimated elevated in women with PCOS.83

that the prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance

and T2D was as high as 31% to 35%, and 7.5% to 20%, Patient evaluation

respectively, in women with PCOS by their fourth

decade, and the risks were significantly higher at all Clinical features

ages and all weights even in young or lean subjects The history-taking should include detailed inquiry

with PCOS.66,67 In Hong Kong, the prevalence of T2D about growth and sexual development, menstrual

under 35 years old is 0.6% in the general population, pattern, reproductive history, medical and drug

but 7.5% in women with PCOS.68 history, symptoms of androgen excess, co-existing

Dyslipidaemia is the most common metabolic cardiovascular risk factors such as tobacco and

abnormality in PCOS. Most studies of women alcohol use, and family history. Drug history is

with PCOS have demonstrated low high-density important as a history or current use of sodium

lipoprotein cholesterol and high triglyceride valproate has been shown to be associated with

concentrations, consistent with their insulin PCOS.

resistance, as well as an increase in low-density During the physical examination, it is essential

lipoprotein cholesterol.69-71 to search for signs of androgen excess (hirsutism,

Metabolic syndrome, characterised by a cluster acne, androgenic alopecia) and insulin resistance

of cardiometabolic risk factors associated with in- (acanthosis nigricans). Modified Ferriman-Gallwey

sulin resistance, is a disease with a large health impact scoring is the method generally used to evaluate

as it confers a 5-fold increase in risk of T2D and a clinical hirsutism, but is affected by subjective

Hong Kong Med J ⎥ Volume 23 Number 6 ⎥ December 2017 ⎥ www.hkmj.org 627

# Yau et al #

variability and cosmetic treatments. It has been exclude late-onset CAH and the 1-mg overnight

suggested that in East Asian patients, a lower cut-off dexamethasone suppression test to exclude

of the modified Ferriman-Gallwey score (of 3) Cushing’s syndrome. It is sometimes noted that

should be used instead of the usual cut-off of 8.16,19 women with PCOS have mildly elevated prolactin.20

As cosmetic hair removal is common in many Asian If the level of 17-hydroxyprogesterone is borderline

countries, evaluation of hirsutism should always elevated, a short synacthen test with measurement

include enquiry about any previous hair-removal of 17-hydroxyprogesterone may be indicated to

procedures. Assessment of blood pressure, BMI, exclude late-onset CAH.19

and waist circumference is also essential. Features Assessment of cardiovascular risk factors

of virilisation, Cushing’s syndrome, and thyroid includes an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

dysfunction should also be looked for and excluded.19 and fasting lipid profiles. Fasting glucose, although

more convenient, has been shown to underestimate

Biochemical features diabetes prevalence and cardiovascular risk when

Laboratory measurements should include tests compared with OGTT, particularly in obese subjects.

to achieve the diagnosis, exclude other endocrine Measuring fasting glucose alone is therefore

problems, and evaluate cardiovascular risk factors. inadequate for the assessment of dysglycaemia in

In someone with clinical signs of hyperandrogenism, women with PCOS.84 Patients with normal glucose

one could argue that biochemical testing is not tolerance should be re-screened at least once every 2

necessary according to current diagnostic criteria. years, or more frequently if additional risk factors are

Most expert groups, however, suggest measuring identified. Patients with impaired glucose tolerance

total testosterone concentration in women who should be screened annually for development of

present with hirsutism. Women with PCOS mostly T2D.

have high-normal or borderline elevated levels of

testosterone. Ultrasound features

Elevated total testosterone is the most direct The use of ultrasound in the diagnosis of PCOS

evidence for androgen excess, but it is important must be tempered by an awareness of the broad

to note that most assays are relatively inaccurate at spectrum of women with ultrasonographic findings

the lower levels present in females, and use of mass characteristic of polycystic ovaries.85 If the patient

spectrometry–based assays of total testosterone are has both oligo-ovulation and hyperandrogenism,

more accurate and preferred.9 Measurement of free a transvaginal ultrasound to document polycystic

testosterone is a more sensitive test, but commer- ovaries is not necessary according to the Rotterdam

cially available free testosterone assays are often criteria. In women who are ready to conceive,

unreliable. The free testosterone index, calculated ultrasound can be used to monitor and document

by total testosterone divided by SHBG, is considered ovulation.

more reliable but is not routinely performed due to The ultrasound criteria in the diagnosis of PCOS

the high cost of measuring SHBG.9 Serum LH and have evolved since the first ultrasound description of

FSH levels should be measured at the early follicular polycystic ovaries in 1986.8 The Rotterdam criteria

phase of the menstrual cycle. Ovulatory assessment described polycystic ovaries as the presence of

such as mid-luteal progesterone measurement is ≥12 follicles in each ovary measuring 2 to 9 mm in

sometimes required in patients seeking infertility diameter and/or increased ovarian volume of >10 mL.

treatment. In rare instances where there are rapidly One ovary fulfilling this definition is sufficient to

progressive features of hyperandrogenism, virilising define polycystic ovaries. More recently, it has

symptoms, or markedly elevated androgen levels been proposed that if newer technology such as

(such as a serum testosterone >5 nmol/L), additional ultrasound machines with transducer frequency

investigations to exclude an androgen-secreting of ≥8 MHz are available, then raising the follicle

tumour may be indicated, including checking cortisol, number per ovary to 25 for diagnosing PCOS would

dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, and imaging of the be more specific.86

adrenal glands and ovaries. As mentioned earlier, Ultrasonography is operator-dependent

AMH is implicated in the pathogenesis of PCOS, and and requires expertise. Transvaginal ultrasound

recent studies have highlighted its potential utility in is the method of choice, but is practically difficult

the diagnosis of women with PCOS,16 although no in patients without previous sexual experience.

diagnostic cut-off value has been defined yet due to Transrectal ultrasound examination is an alternative

the heterogeneity between the different AMH assay in women where transvaginal scan is not possible.

methods. Transabdominal ultrasound has poorer resolution,

Blood tests to exclude other endocrine especially in obese subjects. Recent research suggests

problems include thyroid function tests, prolactin, that ultrasound might be useful to supplement the

or tests to exclude other underlying causes of excess diagnosis in the event of ovulatory disturbance

androgens, including 17-hydroxyprogesterone to without hyperandrogenism.12,86,87

628 Hong Kong Med J ⎥ Volume 23 Number 6 ⎥ December 2017 ⎥ www.hkmj.org

# Polycystic ovary syndrome #

Treatment approach Management of hyperandrogenism

The management of women with polycystic ovary As highlighted earlier, administration of an oestrogen-

varies according to the main symptoms and primary containing oral contraceptive has beneficial effects

problem experienced by the patient. The particular on hyperandrogenism. Furthermore, the oral

needs of the patient may change according to different contraceptive pill containing the anti-androgenic

stages of the life course, from adolescence through progestagen cyproterone acetate, administered

to reproductive age.88 Hence management should in cyclical doses, or drospirenone-containing

involve a multidisciplinary approach involving COC might be beneficial for hirsutism.16 The

paediatricians, gynaecologists, endocrinologists, use of cyproterone-containing pills to alleviate

family physicians, dietitians, clinical psychologists, hyperandrogenic symptoms should ideally be

and surgeons, as appropriate.84 limited to short-term use and discontinued 3 to 4

months after symptom resolution due to higher

Management of menstrual irregularity thromboembolic risk than the first-line COC

pills.94 Other anti-androgens, such as finasteride,

Menstrual irregularity is one of the most common

are sometimes used in severe cases of hirsutism,

presenting symptoms of patients with PCOS, and

although again patients need to ensure they avoid

often reflects underlying ovarian dysfunction and

conceiving whilst on anti-androgenic drugs.

anovulation. Chronic anovulation and secondary

In most circumstances, women may elect

amenorrhoea can be associated with endometrial

to use cosmetic measures to treat the clinical

hyperplasia and increased risk of endometrial

manifestations of hyperandrogenism. Different

carcinoma, along with other complications

cosmetic approaches for hair removal—including

associated with amenorrhoea including osteo-

shaving, waxing, and electrolysis—have variable

porosis. Overweight women with PCOS should be

efficacy and duration of effects. Laser therapy in the

encouraged to lose weight; as low as a 5% reduction

form of photoepilation represents a more permanent

in body weight is associated with improvement in

solution but is also more costly.4 Other options for

amenorrhoea.88-90 Previous studies have highlighted

treatment of hirsutism due to hyperandrogenism

that a lifestyle modification programme is associated

include use of topical eflornithine that may help

with improvement in menses, hirsutism, biochemical

reduce excess facial hair.

hyperandrogenism, and insulin resistance.90,91

Progestagens can be administered both as a

diagnostic test to induce progesterone withdrawal, as Management of anovulatory infertility

well as to treat amenorrhoea. Cyclical progestagens, The presence of anovulatory infertility can be

preferably given 12 to 14 days per month, can be investigated by measurement of progesterone in the

used to ensure regular withdrawal bleeding to avoid mid-luteal phase of the menstrual cycle (eg day 21

endometrial hyperplasia, and are associated with of a 28-day cycle, or day 28 of a 35-day cycle), and

less-adverse cardiometabolic effects than combined can help to establish the presence of anovulation.

oestradiol-progestagen pills. Periodic short courses The monitoring of basal body temperature to

of progestogen (2-3 monthly) are an alternative confirm ovulation does not predict ovulation

option. reliably, and is no longer recommended.95 In patients

The use of the combined oral contraceptive with anovulatory infertility, clomiphene treatment

(COC) pill, with its beneficial effects on suppressing is usually considered the first-line treatment.

excess androgen and its manifestations, has been Clomiphene should be started at a low dose (eg 50

a commonly used and convenient treatment mg daily for 5 days per cycle) and gradually increased

for amenorrhoea, with the added benefit of until the lowest effective dose that achieves ovulation

providing contraception. In women with PCOS, is reached, but this requires close monitoring,

COC formulations containing less androgenic especially for the potential side-effects of multiple

progestagens are preferred. Nonetheless, there has pregnancy and ovarian hyperstimulation. Treatment

been some debate about whether the use of COC can be repeated if unsuccessful, but the majority of

may cause exacerbation of cardiometabolic risk.92 patients who respond usually do so within the first

Contra-indications to use of a COC include heavy three cycles.4,96 The highest recommended dose

smokers aged ≥35 years, those with hypertension or for clomiphene is 150 mg, and if the woman still

established cardiac disease, and those with multiple does not respond, second-line treatment should be

cardiovascular risk factors.93 Nevertheless, current considered.

recommendations suggest that this is a useful Metformin has beneficial effects on anovu-

alternative, although clinicians should monitor for lation. In a systematic review and meta-analysis,

changes in body weight, blood pressure, lipid profile metformin was found to be associated with increased

as well as dysglycaemia if patients are prescribed success at inducing ovulation.97 Doses vary in clinical

COC, especially if the patient is overweight. trials from 1 g daily to higher doses. In a multicentre

Hong Kong Med J ⎥ Volume 23 Number 6 ⎥ December 2017 ⎥ www.hkmj.org 629

# Yau et al #

randomised controlled trial, therapy-naїve PCOS Management of cardiometabolic risk

women who received metformin had a significantly Women with PCOS are at substantially increased

lower live birth rate than women who conceived cardiometabolic risk, and therefore should

through clomiphene alone, or were treated with a undergo periodic evaluation of associated risk

combination of clomiphene and metformin.98 The factors.4 Overweight women with PCOS should

use of metformin as a co-treatment with clomiphene undergo comprehensive evaluation by a dietitian,

has been shown to improve ovulation in women and be encouraged to lose weight. Weight loss

with clomiphene-resistant PCOS.99 Metformin of approximately 5% is already associated with

is in general stopped after successful conception, improved metabolic parameters as well as

although some advocate continued use during the reproductive outcome. Even among women with

first trimester to reduce the risk of spontaneous normal BMI, those with PCOS appear to have

miscarriage. This is still an area of controversy, and increased visceral adiposity that contributes to the

the pros and cons of continuing metformin should endogenous insulin resistance, and is correlated with

be carefully discussed. Metformin is known to cross metabolic parameters, fatty liver as well as carotid

the placenta but it has also been shown to be a useful intimal-medial thickness.103

treatment for gestational diabetes. In addition to lifestyle measures, women

Aromatase inhibitors reduce circulating should be screened for glucose intolerance by an

oestrogen levels, lead to a rise in pituitary FSH, and OGTT. Screening using fasting glucose alone is

have previously shown beneficial effects in a meta- inadequate in this high-risk population.4 Presence of

analysis. Letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, was impaired glucose tolerance may warrant treatment

found to be superior to clomiphene in achieving live with metformin given the multiple metabolic and

births in a randomised clinical trial.100 reproductive benefits, regardless of whether there

Daily injections of exogenous gonadotropins, is clinical evidence of insulin resistance. Overt

including recombinant FSH or menopausal diabetes should be treated using an appropriate

gonadotropin, have been found to improve ovulation combination of dietary treatment, metformin, other

induction among women who did not respond to oral glucose-lowering agents, and in some cases,

other treatments. This treatment requires careful insulin. The choice of agent should depend on the

monitoring, and should be used with a ‘chronic low- underlying pathophysiology (eg whether obesity

dose step-up’ approach as outlined by the ESHRE/ is present), but also take into account the fertility

ASRM to avoid multiple pregnancies or ovarian wishes and plans of the patient. Metformin in

hyperstimulation syndrome.96,101 combination with lifestyle intervention has been

found to be associated with greater reduction in

Ovarian surgery/drilling/laparoscopic ovarian BMI compared with lifestyle intervention alone.104

diathermy Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of

Surgical procedures such as ovarian wedge resection thiazolidinediones in improving metabolic para-

or ovarian drilling by diathermy or laser lead to a meters as well as menses and hyperandrogenism

decreased number of antral follicles, reduced ovarian in women with PCOS. Due to possible adverse

androgen production, and improved ovulation.16 effects, however, this class of agent is currently not

Ovarian wedge resection is no longer performed recommended for treatment of insulin resistance

due to the higher extent of adhesion formation and among women with PCOS.4

ovarian tissue damage. Ovarian drilling has been Treatment of hypertension likewise should

used as an alternative to exogenous gonadotropins take into account the fertility wishes of the patient.

for treatment of anovulatory infertility, with Screening for other secondary causes of young-

similar success rates. The main limitations onset hypertension may be necessary, especially

include the potential for formation of adhesions, if atypical features such as proteinuria are present.

and reduced ovarian reserve. In a retrospective Preferred anti-hypertensive agents in women

analysis of Chinese women with PCOS treated by contemplating pregnancy would be the older agents

laser diathermy, spontaneous ovulation rates and such as methyldopa. It is notable that women

cumulative pregnancy rates were similar regardless with pre-existing hypertension are more likely

of the presence or absence of metabolic syndrome.102 to develop hypertension-related complications

during pregnancy, and therefore require more strict

surveillance during pregnancy. Hyperlipidaemia can

Assisted reproductive procedures

be managed using dietary measures, and in some

In women who fail second-line treatment such as cases, lipid-lowering agents such as HMG CoA

metformin, ovarian drilling or ovarian stimulation (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A) reductase

with gonadotropins, third-line treatment such as inhibitors. If there are plans for pregnancy, drug

intrauterine insemination or in-vitro fertilisation treatment with lipid-lowering treatment should be

can be considered.17 withheld.

630 Hong Kong Med J ⎥ Volume 23 Number 6 ⎥ December 2017 ⎥ www.hkmj.org

# Polycystic ovary syndrome #

Psychological distress, anxiety, and depression Acknowledgement

are common among women with PCOS, and may

be linked to some of the skin complications such as RCW Ma acknowledges support from the Research

hirsutism and acne or presence of menstrual and Grants Council General Research Fund (Ref.

fertility problems; all these impact on psychological 14110415).

well-being. Clinicians need to have a high level of

awareness and screen for these symptoms when Declaration

appropriate and offer the necessary referrals for All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

psychological support. Sleep-disordered breathing

including obstructive sleep apnoea is also common, References

impacts sleep quality, and can exacerbate both 1. Stein IF, Leventhal ML. Amenorrhea associated with

mood problems as well as cardiometabolic risk. It bilateral polycystic ovaries. Am J Obstet Gynecol

should be screened for and managed accordingly. 1935;29:181-91.

In those with marked obesity, bariatric surgery 2. March WA, Moore VM, Willson KJ, Phillips DI, Norman

is an option to address obesity and associated RJ, Davies MJ. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome

in a community sample assessed under contrasting

metabolic abnormalities. Interestingly, a systematic

diagnostic criteria. Hum Reprod 2010;25:544-51.

review including 13 primary studies found that the

3. Chen X, Yang D, Mo Y, Li L, Chen Y, Huang Y. Prevalence

incidence of PCOS was reduced from 45.6% to 7.1% of polycystic ovary syndrome in unselected women

after bariatric surgery.105 from southern China. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol

The screening and management of metabolic 2008;139:59-64.

abnormalities is particularly relevant in those 4. Legro RS, Arslanian SA, Ehrmann DA, et al. Diagnosis

women with PCOS who are planning a pregnancy or and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine

undergoing fertility treatment. Women with PCOS Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab

are at increased risk of different complications 2013;98:4565-92.

including gestational diabetes and pre-eclampsia. 5. Gibson-Helm M, Teede H, Dunaif A, Dokras A. Delayed

Undiagnosed gestational diabetes/maternal diagnosis and a lack of information associated with

dissatisfaction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

hyperglycaemia or poorly controlled blood pressure

J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102:604-12.

all contribute to poorer pregnancy outcome among

6. Zawadski J, Dunaif A. Diagnostic criteria for polycystic

women with PCOS. Optimal management before ovary syndrome: towards a rational approach. In: Dunaif A,

pregnancy and intrapartum can help to minimise the Givens JR, Haseltine FP, Merriam GR, editors. Polycystic

risk of these pregnancy complications. ovary syndrome. Boston: Blackwell Scientific Publications;

1992: 377-84.

Conclusions 7. Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus

Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic

Polycystic ovary syndrome is a multi-faceted criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic

syndrome that is becoming increasingly recognised, ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 2004;81:19-25.

and is an important contributor to multiple medical 8. Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, et al. The Androgen

and reproductive problems. As illustrated in Excess and PCOS Society criteria for the polycystic ovary

this review, given the multiple reproductive and syndrome: the complete task force report. Fertil Steril

metabolic complications associated with PCOS, 2009;91:456-88.

9. Rosner W, Auchus RJ, Azziz R, Sluss PM, Raff H. Position

patients may seek medical attention via a variety

statement: utility, limitations, and pitfalls in measuring

of different channels, and may present to clinicians

testosterone: an Endocrine Society position statement. J

through different disciplines. Clinicians therefore Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:405-13.

need to recognise the multi-faceted nature of this 10. Evidence-based Methodology Workshop on Polycystic

complex disorder and be aware of the associated Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). December 3-5, 2012. Available

complications. Diagnostic criteria are still evolving, from: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/about/meetings/2012/

although currently the Rotterdam criteria remain the Pages/120512.aspx. Accessed 10 Jul 2017.

most widely accepted. Given the burden of metabolic 11. Lam PM, Ma RC, Cheung LP, Chow CC, Chan JC, Haines

complications associated with the disorder, there has CJ. Polycystic ovarian syndrome in Hong Kong Chinese

been much recent discussion regarding the potential women: patient characteristics and diagnostic criteria.

need to rename the syndrome to better highlight its Hong Kong Med J 2005;11:336-41.

12. Boyle JA, Teede HJ. PCOS: Refining diagnostic features in

metabolic consequences, in addition to the known

PCOS to optimize health outcomes. Nat Rev Endocrinol

reproductive features. The long-term risks of the

2016;12:630-1.

different complications are still not clearly defined, 13. Rojas J, Chávez M, Olivar L, et al. Polycystic ovary

given the scarcity of well-conducted prospective syndrome, insulin resistance, and obesity: navigating

studies. These limitations in our current knowledge the pathophysiologic labyrinth. Int J Reprod Med

highlight the need to follow-up this group of high- 2014;2014:719050.

risk women. 14. Cheung LP. Polycystic ovary syndrome: not only a

Hong Kong Med J ⎥ Volume 23 Number 6 ⎥ December 2017 ⎥ www.hkmj.org 631

# Yau et al #

gynaecological disease. J Paediatr Obstet Gynaecol response to adrenocorticotropin in hyperandrogenic

2008(May/Jun):125-31. women: apparent relative impairment of 17,20-lyase

15. Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Piperi C. Genetics of polycystic activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996;81:881-6.

ovary syndrome: searching for the way out of the labyrinth. 34. Yki-Järvinen H, Mäkimattila S, Utriainen T, Rutanen

Hum Reprod Update 2005;11:631-43. EM. Portal insulin concentrations rather than insulin

16. Azziz R, Carmina E, Chen Z, et al. Polycystic ovary sensitivity regulate serum sex hormone-binding globulin

syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016;2:16057. and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 in vivo. J

17. Goodarzi MO, Dumesic DA, Chazenbalk G, Azziz R. Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995;80:3227-32.

Polycystic ovary syndrome: etiology, pathogenesis and 35. Poretsky L, Cataldo NA, Rosenwaks Z, Giudice LC. The

diagnosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011;7:219-31. insulin-related ovarian regulatory system in health and

18. Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, et al. Positions statement: disease. Endocr Rev 1999;20:535-82.

criteria for defining polycystic ovary syndrome as a 36. Gambineri A, Patton L, Altieri P, et al. Polycystic ovary

predominantly hyperandrogenic syndrome: an Androgen syndrome is a risk factor for type 2 diabetes: results from a

Excess Society guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab long-term prospective study. Diabetes 2012;61:2369-74.

2006;91:4237-45. 37. Bremer AA, Miller WL. The serine phosphorylation

19. McCartney CR, Marshall JC. Clinical practice. Polycystic hypothesis of polycystic ovary syndrome: a unifying

ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2016;375:54-64. mechanism for hyperandrogenemia and insulin resistance.

20. Franks S. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med Fertil Steril 2008;89:1039-48.

1995;333:853-61. 38. Corbould A, Kim YB, Youngren JF, et al. Insulin resistance

21. Agarwal SK, Judd HL, Magoffin DA. A mechanism for the in the skeletal muscle of women with PCOS involves

suppression of estrogen production in polycystic ovary intrinsic and acquired defects in insulin signaling. Am J

syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996;81:3686-91. Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2005;288:E1047-54.

22. Jakimiuk AJ, Weitsman SR, Magoffin DA. 5alpha-reductase 39. Dunaif A, Segal KR, Futterweit W, Dobrjansky A. Profound

activity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin peripheral insulin resistance, independent of obesity, in

Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:2414-8. polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes 1989;38:1165-74.

23. Moghetti P, Castello R, Negri C, et al. Metformin effects 40. Stepto NK, Cassar S, Joham AE, et al. Women with

on clinical features, endocrine and metabolic profiles, polycystic ovary syndrome have intrinsic insulin resistance

and insulin sensitivity in polycystic ovary syndrome: a on euglycaemic-hyperinsulaemic clamp. Hum Reprod

randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 6-month 2013;28:777-84.

trial, followed by open, long-term clinical evaluation. J Clin 41. Legro RS. Diabetes prevalence and risk factors in

Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:139-46. polycystic ovary syndrome. Obstet Gynecol Clin North

24. Bergh C, Carlsson B, Olsson JH, Selleskog U, Hillensjö T. Am 2001;28:99-109.

Regulation of androgen production in cultured human 42. Dunaif A, Finegood DT. Beta-cell dysfunction independent

thecal cells by insulin-like growth factor I and insulin. of obesity and glucose intolerance in the polycystic ovary

Fertil Steril 1993;59:323-31. syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996;81:942-7.

25. Balen AH, Conway G, Homburg R, Legro R. Polycystic 43. Ehrmann DA, Kasza K, Azziz R, Legro RS, Ghazzi MN;

ovary syndrome: A guide to clinical management. UK: PCOS/Troglitazone Study Group. Effects of race and

Taylor & Francis; 2006. family history of type 2 diabetes on metabolic status of

26. Franks S, Gilling-Smith C, Watson H, Willis D. Insulin women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol

action in the normal and polycystic ovary. Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:66-71.

Metab Clin North Am 1999;28:361-78. 44. Dunaif A, Wu X, Lee A, Diamanti-Kandarakis E. Defects

27. Knight PG, Glister C. Local roles of TGF-beta superfamily in insulin receptor signaling in vivo in the polycystic

members in the control of ovarian follicle development. ovary syndrome (PCOS). Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab

Anim Reprod Sci 2003;78:165-83. 2001;281:E392-9.

28. Seifer DB, MacLaughlin DT, Cuckle HS. Serum mullerian- 45. Ciaraldi TP, Aroda V, Mudaliar S, Chang RJ, Henry RR.

inhibiting substance in Down’s syndrome pregnancies. Polycystic ovary syndrome is associated with tissue-

Hum Reprod 2007;22:1017-20. specific differences in insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol

29. Visser JA, de Jong FH, Laven JS, Themmen AP. Anti- Metab 2009;94:157-63.

Müllerian hormone: a new marker for ovarian function. 46. Ciaraldi TP. Molecular defects of insulin action in the

Reproduction 2006;131:1-9. polycystic ovary syndrome: possible tissue specificity. J

30. Pellatt L, Hanna L, Brincat M, et al. Granulosa cell Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2000;13 Suppl 5:1291-3.

production of anti-Müllerian hormone is increased in 47. Ibáñez L, Sebastiani G, Diaz M, Gómez-Roig MD, Lopez-

polycystic ovaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:240-5. Bermejo A, de Zegher F. Low body adiposity and high

31. Dunaif A. Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary leptinemia in breast-fed infants born small-for-gestational-

syndrome: mechanism and implications for pathogenesis. age. J Pediatr 2010;156:145-7.

Endocr Rev 1997;18:774-800. 48. Virtue S, Vidal-Puig A. It’s not how fat you are, it’s what you

32. Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Argyrakopoulou G, Economou F, do with it that counts. PLoS Biol 2008;6:e237.

Kandaraki E, Koutsilieris M. Defects in insulin signaling 49. Virtue S, Vidal-Puig A. Adipose tissue expandability,

pathways in ovarian steroidogenesis and other tissues in lipotoxicity and the metabolic syndrome—an allostatic

polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). J Steroid Biochem Mol perspective. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010;1801:338-49.

Biol 2008;109:242-6. 50. Chazenbalk G, Trivax BS, Yildiz BO, et al. Regulation of

33. Moghetti P, Castello R, Negri C, et al. Insulin infusion adiponectin secretion by adipocytes in the polycystic ovary

amplifies 17 alpha-hydroxycorticosteroid intermediates syndrome: role of tumor necrosis factor-{alpha}. J Clin

632 Hong Kong Med J ⎥ Volume 23 Number 6 ⎥ December 2017 ⎥ www.hkmj.org

# Polycystic ovary syndrome #

Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:935-42. SF. Risk of T2DM and impaired fasting glucose among

51. Barber TM, Franks S. Adipocyte biology in polycystic PCOS subjects: results of an 8-year follow-up. Curr Diab

ovary syndrome. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2013;373:68-76. Rep 2006;6:77-83.

52. Padmanabhan V, Manikkam M, Recabarren S, Foster D. 68. Cheung LP, Ma RC, Lam PM, et al. Cardiovascular risks and

Prenatal testosterone excess programs reproductive and metabolic syndrome in Hong Kong Chinese women with

metabolic dysfunction in the female. Mol Cell Endocrinol polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod 2008;23:1431-8.

2006;246:165-74. 69. Berneis K, Rizzo M, Lazzarini V, Fruzzetti F, Carmina

53. Dumesic DA, Schramm RD, Abbott DH. Early origins of E. Atherogenic lipoprotein phenotype and low-density

polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod Fertil Dev 2005;17:349- lipoproteins size and subclasses in women with polycystic

60. ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:186-

54. Legro RS, Bentley-Lewis R, Driscoll D, Wang SC, Dunaif A. 9.

Insulin resistance in the sisters of women with polycystic 70. Phelan N, O’Connor A, Kyaw-Tun T, et al. Lipoprotein

ovary syndrome: association with hyperandrogenemia subclass patterns in women with polycystic ovary syndrome

rather than menstrual irregularity. J Clin Endocrinol (PCOS) compared with equally insulin-resistant women

Metab 2002;87:2128-33. without PCOS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:3933-9.

55. Hickey M, Sloboda DM, Atkinson HC, et al. The relationship 71. Valkenburg O, Steegers-Theunissen RP, Smedts HP, et al.

between maternal and umbilical cord androgen levels and A more atherogenic serum lipoprotein profile is present

polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescence: a prospective in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a case-control

cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:3714-20. study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:470-6.

56. Dumesic DA, Oberfield SE, Stener-Victorin E, Marshall JC, 72. Isomaa B, Almgren P, Tuomi T, et al. Cardiovascular

Laven JS, Legro RS. Scientific statement on the diagnostic morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic

criteria, epidemiology, pathophysiology, and molecular syndrome. Diabetes Care 2001;24:683-9.

genetics of polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocr Rev 73. Weerakiet S, Bunnag P, Phakdeekitcharoen B, et al.

2015;36:487-525. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in Asian women

57. Hayes MG, Urbanek M, Ehrmann DA, et al. Genome- with polycystic ovary syndrome: using the International

wide association of polycystic ovary syndrome implicates Diabetes Federation criteria. Gynecol Endocrinol

alterations in gonadotropin secretion in European ancestry 2007;23:153-60.

populations. Nat Commun 2015;6:7502. 74. Vgontzas AN, Legro RS, Bixler EO, Grayev A, Kales A,

58. Boomsma CM, Eijkemans MJ, Hughes EG, Visser GH, Chrousos GP. Polycystic ovary syndrome is associated

Fauser BC, Macklon NS. A meta-analysis of pregnancy with obstructive sleep apnea and daytime sleepiness: role

outcomes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum of insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:517-

Reprod Update 2006;12:673-83. 20.

59. Weerakiet S, Srisombut C, Rojanasakul A, Panburana P, 75. Gopal M, Duntley S, Uhles M, Attarian H. The role of

Thakkinstian A, Herabutya Y. Prevalence of gestational obesity in the increased prevalence of obstructive sleep

diabetes mellitus and pregnancy outcomes in Asian women apnea syndrome in patients with polycystic ovarian

with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol syndrome. Sleep Med 2002;3:401-4.

2004;19:134-40. 76. Wild S, Pierpoint T, McKeigue P, Jacobs H. Cardiovascular

60. Qin JZ, Pang LH, Li MJ, Fan XJ, Huang RD, Chen HY. disease in women with polycystic ovary syndrome at

Obstetric complications in women with polycystic ovary long-term follow-up: a retrospective cohort study. Clin

syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Endocrinol (Oxf ) 2000;52:595-600.

Biol Endocrinol 2013;11:56. 77. Lo JC, Feigenbaum SL, Yang J, Pressman AR, Selby JV, Go

61. Chittenden BG, Fullerton G, Maheshwari A, Bhattacharya AS. Epidemiology and adverse cardiovascular risk profile

S. Polycystic ovary syndrome and the risk of gynaecological of diagnosed polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol

cancer: a systematic review. Reprod Biomed Online Metab 2006;91:1357-63.

2009;19:398-405. 78. Cibula D, Cifkova R, Fanta M, Poledne R, Zivny J, Skibova

62. Haoula Z, Salman M, Atiomo W. Evaluating the association J. Increased risk of non-insulin dependent diabetes

between endometrial cancer and polycystic ovary mellitus, arterial hypertension and coronary artery disease

syndrome. Hum Reprod 2012;27:1327-31. in perimenopausal women with a history of the polycystic

63. Timmermans A, Opmeer BC, Khan KS, et al. Endometrial ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod 2000;15:785-9.

thickness measurement for detecting endometrial cancer 79. Schmidt J, Landin-Wilhelmsen K, Brännström M,

in women with postmenopausal bleeding: a systematic Dahlgren E. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors in

review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:160-7. PCOS women of postmenopausal age: a 21-year controlled

64. Sartor BM, Dickey RP. Polycystic ovarian syndrome and follow-up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:3794-

the metabolic syndrome. Am J Med Sci 2005;330:336-42. 803.

65. Colilla S, Cox NJ, Ehrmann DA. Heritability of insulin 80. Shroff R, Kerchner A, Maifeld M, Van Beek EJ, Jagasia

secretion and insulin action in women with polycystic D, Dokras A. Young obese women with polycystic ovary

ovary syndrome and their first degree relatives. J Clin syndrome have evidence of early coronary atherosclerosis.

Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:2027-31. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:4609-14.

66. Legro RS, Gnatuk CL, Kunselman AR, Dunaif A. Changes 81. Luque-Ramirez M, Mendieta-Azcona C, Alvarez-Blasco F,

in glucose tolerance over time in women with polycystic Escobar-Morreale HF. Androgen excess is associated with

ovary syndrome: a controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol the increased carotid intima-media thickness observed

Metab 2005;90:3236-42. in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum

67. Boudreaux MY, Talbott EO, Kip KE, Brooks MM, Witchel Reprod 2007;22:3197-203.

Hong Kong Med J ⎥ Volume 23 Number 6 ⎥ December 2017 ⎥ www.hkmj.org 633

# Yau et al #

82. Talbott EO, Zborowski JV, Rager JR, Boudreaux MY, contraceptive use. 2015. Available from: http://apps.who.

Edmundowicz DA, Guzick DS. Evidence for an association int/iris/bitstream/10665/181468/1/9789241549158_eng.

between metabolic cardiovascular syndrome and coronary pdf. Accessed 10 Jul 2017.

and aortic calcification among women with polycystic 94. The Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare of the

ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:5454- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (FSRH).

61. FSRH Statement: Venous thromboembolism (VTE) and

83. Boulman N, Levy Y, Leiba R, et al. Increased C-reactive hormonal contraception Nov 2014. Available from: https://

protein levels in the polycystic ovary syndrome: a marker www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/fsr

of cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab hstatementvteandhormonalcontraception-november/.

2004;89:2160-5. Accessed 10 Jul 2017.

84. Fauser BC, Tarlatzis BC, Rebar RW, et al. Consensus on 95. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Fertility

women’s health aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome problems: assessment and treatment. 20 Feb 2013.

(PCOS): the Amsterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg156.

3rd PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Fertil Steril Accessed 10 Jul 2017.

2012;97:28-38.e25. 96. Jayasena CN, Franks S. The management of patients

85. Johnstone EB, Rosen MP, Neril R, et al. The polycystic with polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat Rev Endocrinol

ovary post-rotterdam: a common, age-dependent finding 2014;10:624-36.

in ovulatory women without metabolic significance. J Clin 97. Lord JM, Flight IH, Norman RJ. Metformin in polycystic

Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:4965-72. ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis.

86. Dewailly D, Lujan ME, Carmina E, et al. Definition and BMJ 2003;327:951-3.

significance of polycystic ovarian morphology: a task force 98. Legro RS, Barnhart HX, Schlaff WD, et al. Clomiphene,

report from the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary metformin, or both for infertility in the polycystic ovary

Syndrome Society. Hum Reprod Update 2014;20:334-52. syndrome. N Engl J Med 2007;356:551-66.

87. Quinn MM, Kao CN, Ahmad A, et al. Raising threshold 99. Moll E, van der Veen F, van Wely M. The role of metformin

for diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome excludes in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review. Hum

population of patients with metabolic risk. Fertil Steril Reprod Update 2007;13:527-37.

2016;106:1244-51. 100. Legro RS, Brzyski RG, Diamond MP, et al. Letrozole versus

88. Conway G, Dewailly D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, et al. The clomiphene for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome.

polycystic ovary syndrome: a position statement from N Engl J Med 2014;371:119-29.

the European Society of Endocrinology. Eur J Endocrinol 101. Thessaloniki ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus

2014;171:P1-29. Workshop Group. Consensus on infertility treatment

89. Moran LJ, Noakes M, Clifton PM, Tomlinson L, Galletly C, related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod

Norman RJ. Dietary composition in restoring reproductive 2008;23:462-77.

and metabolic physiology in overweight women with 102. Kong GW, Cheung LP, Lok IH. Effects of laparoscopic

polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab ovarian drilling in treating infertile anovulatory polycystic

2003;88:812-9. ovarian syndrome patients with and without metabolic

90. Moran LJ, Hutchison SK, Norman RJ, Teede HJ. Lifestyle syndrome. Hong Kong Med J 2011;17:5-10.

changes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. 103. Ma RC, Liu KH, Lam PM, et al. Sonographic measurement

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(7):CD007506. of mesenteric fat predicts presence of fatty liver among

91. Pasquali R, Gambineri A, Pagotto U. The impact of subjects with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol

obesity on reproduction in women with polycystic ovary Metab 2011;96:799-807.

syndrome. BJOG 2006;113:1148-59. 104. Naderpoor N, Shorakae S, de Courten B, Misso ML,

92. Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Baillargeon JP, Iuorno MJ, Moran LJ, Teede HJ. Metformin and lifestyle modification

Jakubowicz DJ, Nestler JE. A modern medical quandary: in polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-

polycystic ovary syndrome, insulin resistance, and oral analysis. Hum Reprod Update 2015;21:560-74.

contraceptive pills. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:1927- 105. Skubleny D, Switzer NJ, Gill RS, et al. The impact of bariatric

32. surgery on polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review

93. World Health Organization. Medical eligibility criteria for and meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2016;26:169-76.

634 Hong Kong Med J ⎥ Volume 23 Number 6 ⎥ December 2017 ⎥ www.hkmj.org

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Current Aspects of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome A Literature ReviewDocumento5 pagineCurrent Aspects of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome A Literature ReviewlizandrobNessuna valutazione finora

- Seminar: Robert J Norman, Didier Dewailly, Richard S Legro, Theresa E HickeyDocumento13 pagineSeminar: Robert J Norman, Didier Dewailly, Richard S Legro, Theresa E HickeyMédica Consulta ExternaNessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis of Polycystic Ovarian SyndromeDocumento9 pagineClinical Presentation and Diagnosis of Polycystic Ovarian SyndromeLia MeivianeNessuna valutazione finora

- Primary and Secondary Prevention of Metabolic and Cardiovascular Comorbidities in Women With Polycystic Ovary SyndromeDocumento8 paginePrimary and Secondary Prevention of Metabolic and Cardiovascular Comorbidities in Women With Polycystic Ovary SyndromeMelisa Viviana Zapata NavarroNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 - Pcos Tog 2017Documento11 pagine3 - Pcos Tog 2017Siti NurfathiniNessuna valutazione finora

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome 2016 NEJMDocumento11 paginePolycystic Ovary Syndrome 2016 NEJMGabrielaNessuna valutazione finora

- 6 - Contemporary Management of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome - 2019Documento11 pagine6 - Contemporary Management of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome - 2019Johanna Bustos NutricionistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Polycystic Ovary, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity on Women Health: Volume 8: Frontiers in Gynecological EndocrinologyDa EverandImpact of Polycystic Ovary, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity on Women Health: Volume 8: Frontiers in Gynecological EndocrinologyNessuna valutazione finora

- LECTURE 24 Polycystic Ovary SyndromeDocumento13 pagineLECTURE 24 Polycystic Ovary SyndromeCharisse Angelica MacedaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 s2.0 S0026049517302743 MainDocumento11 pagine1 s2.0 S0026049517302743 MainTeodora OnofreiNessuna valutazione finora

- Diagnosis and Management of Adoslecent PCOS 2020Documento11 pagineDiagnosis and Management of Adoslecent PCOS 2020Awan AndrawinuNessuna valutazione finora

- Polycystic Ovary SyndromeDocumento13 paginePolycystic Ovary SyndromeLIZARDO CRUZADO DIAZNessuna valutazione finora

- 7 FixDocumento5 pagine7 FixalmubarakhNessuna valutazione finora

- China PCOSDocumento14 pagineChina PCOSMayene ChavezNessuna valutazione finora

- ReviewDocumento13 pagineReviewNelly ElizabethNessuna valutazione finora

- An Update of Genetic BasisDocumento10 pagineAn Update of Genetic BasisHAVIZ YUADNessuna valutazione finora

- AACE/ACE Disease State Clinical ReviewDocumento10 pagineAACE/ACE Disease State Clinical ReviewSanjay NavaleNessuna valutazione finora

- MetforminDocumento14 pagineMetforminnidyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Polycystic Ovary SyndromeDocumento13 paginePolycystic Ovary SyndromeNAYSHA YANET CHAVEZ RONDINELNessuna valutazione finora

- Polycystic Ovary SyndromeDocumento11 paginePolycystic Ovary SyndromeViridiana Briseño GarcíaNessuna valutazione finora

- 3.review of Literature PDFDocumento38 pagine3.review of Literature PDFJalajarani AridassNessuna valutazione finora

- Theft of Womanhood - Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: Role of HomeopathyDocumento11 pagineTheft of Womanhood - Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: Role of HomeopathyMadhukar KNessuna valutazione finora

- Ovario PoliqDocumento16 pagineOvario PoliqlizethNessuna valutazione finora

- Acog 194Documento15 pagineAcog 194Marco DiestraNessuna valutazione finora

- Endocrinology & Metabolic SyndromeDocumento13 pagineEndocrinology & Metabolic SyndromeMayra PereiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences: 20 October 2011Documento8 pagineRajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences: 20 October 2011Manali JainNessuna valutazione finora

- Kri Edt 2018Documento5 pagineKri Edt 2018Teguh Imana NugrahaNessuna valutazione finora

- Whats New of PcosDocumento9 pagineWhats New of PcosbambangNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 27 The Polycystic Ovary SyndromeDocumento4 pagineChapter 27 The Polycystic Ovary Syndromepmj050gpNessuna valutazione finora

- Polycysticovarysyndrome Inadolescents: Selma Feldman Witchel,, Hailey Roumimper,, Sharon OberfieldDocumento16 paginePolycysticovarysyndrome Inadolescents: Selma Feldman Witchel,, Hailey Roumimper,, Sharon OberfieldAgustina S. SelaNessuna valutazione finora

- ARPCKD Bombay J 2012Documento4 pagineARPCKD Bombay J 2012micamica451Nessuna valutazione finora

- Insulin Resistance and PCOS-dr. Hilma Final 11 Juli 2021 FIXDocumento48 pagineInsulin Resistance and PCOS-dr. Hilma Final 11 Juli 2021 FIXputrihealthirezaNessuna valutazione finora

- Fitzgerald 2018Documento7 pagineFitzgerald 2018Derevie Hendryan MoulinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Resistencia InsulinaDocumento13 pagineResistencia InsulinaNutrición MxNessuna valutazione finora

- Clep 6 001 PDFDocumento13 pagineClep 6 001 PDFJaila NatashaNessuna valutazione finora

- GWAS PCOS KoreaDocumento9 pagineGWAS PCOS KoreaedwardNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal Pcos InternationalDocumento5 pagineJurnal Pcos InternationalPuput Anistiya Hariani100% (1)

- Jeanes 2017Documento9 pagineJeanes 2017ThormmmNessuna valutazione finora

- Costello 2007Documento10 pagineCostello 2007ThormmmNessuna valutazione finora

- PCOS-Journal Article 2Documento8 paginePCOS-Journal Article 2dinarosman02Nessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal 7Documento10 pagineJurnal 7Ade Yurga TonaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Throughout A Woman's LifeDocumento15 paginePolycystic Ovary Syndrome Throughout A Woman's LifeMDLuchoNessuna valutazione finora

- Metformin in PCOSDocumento5 pagineMetformin in PCOSbalaramNessuna valutazione finora

- GYNE - Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS)Documento7 pagineGYNE - Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS)Alodia Razon100% (1)

- Jpe 3 E05Documento6 pagineJpe 3 E05amirreza jmNessuna valutazione finora

- ICP AnnalsofhepatologyDocumento4 pagineICP AnnalsofhepatologyArnella HutagalungNessuna valutazione finora

- Association of Clinical Features With Obesity and Gonadotropin Levels in Women With Polycystic Ovarian SyndromeDocumento4 pagineAssociation of Clinical Features With Obesity and Gonadotropin Levels in Women With Polycystic Ovarian Syndromedoctor wajihaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pregnancy Complications in Women With PCOS: A Meta-Analysis: KM Tanvir and Mohammad Lutfor RahmanDocumento6 paginePregnancy Complications in Women With PCOS: A Meta-Analysis: KM Tanvir and Mohammad Lutfor Rahmanmr1998goNessuna valutazione finora

- Rosenfield2015 PDFDocumento27 pagineRosenfield2015 PDFdanilacezaraalinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Report: Pregnancy in An Infertile Woman With Polycystic Ovary SyndromeDocumento4 pagineCase Report: Pregnancy in An Infertile Woman With Polycystic Ovary SyndromeEunice PalloganNessuna valutazione finora

- Polycystic Ovary SyndromeDocumento6 paginePolycystic Ovary SyndromealemNessuna valutazione finora

- Female Genomics Infertility and Overall Health Joshi 2017Documento8 pagineFemale Genomics Infertility and Overall Health Joshi 2017Orlando CuellarNessuna valutazione finora

- Survey of Poly Cystic Ovarian Disease (PCOD) Among The Girl Students of Bishop Heber College, Trichirapalli, Tamil Nadu, IndiaDocumento9 pagineSurvey of Poly Cystic Ovarian Disease (PCOD) Among The Girl Students of Bishop Heber College, Trichirapalli, Tamil Nadu, IndiayooyoNessuna valutazione finora

- Survey of Poly Cystic Ovarian Disease (PCOD) Among The Girl Students of Bishop Heber College, Trichirapalli, Tamil Nadu, IndiaDocumento9 pagineSurvey of Poly Cystic Ovarian Disease (PCOD) Among The Girl Students of Bishop Heber College, Trichirapalli, Tamil Nadu, IndiayooyoNessuna valutazione finora

- Jama Huddleston 2022 It 210031 1641843898.23442Documento2 pagineJama Huddleston 2022 It 210031 1641843898.23442Davi LeocadioNessuna valutazione finora

- Hyperemesis Gravidarum 2019 NatureDocumento17 pagineHyperemesis Gravidarum 2019 NatureResidentes GinecologíaNessuna valutazione finora

- Abdominal Adiposity and The Polycystic Ovary SyndromeDocumento7 pagineAbdominal Adiposity and The Polycystic Ovary SyndromeclinicacosimoNessuna valutazione finora

- Aub 15Documento28 pagineAub 15Nadiah Baharum ShahNessuna valutazione finora

- Hormonal Contraception in Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Choices, Challenges, and Noncontraceptive BenefitsDocumento11 pagineHormonal Contraception in Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Choices, Challenges, and Noncontraceptive BenefitsMariam QaisNessuna valutazione finora

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 9: GynecologyDa EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 9: GynecologyNessuna valutazione finora