Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

JD Byrider Judgment

Caricato da

Jim Kinney0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

19K visualizzazioni8 pagineThis ruling in response to Massachusetts Attorney General

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoThis ruling in response to Massachusetts Attorney General

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

19K visualizzazioni8 pagineJD Byrider Judgment

Caricato da

Jim KinneyThis ruling in response to Massachusetts Attorney General

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 8

nowReL ovtansee CD NOTIEY

“CAG/SaK, Commonwealth v. Venturcap Investment oli@ VN et al.

LAD AAD,

? Suffolk County Superior Court Action No. 1784CV03081-BLS1

~PLA] say. :

Decision and Order Regarding Commonwealth's Motion for Partial Summary

Judgment (Docket Entry No. 19): \

Piaintiff Commonwealth of Massachusetts (‘Commonwealth’), by and through its

‘Attorney General, Maura Healey, filed this enforcement action in September 2017

against defendants Venturcap Investment Group V, LLC, doing business as JD Byrider, i

and Venturcap Financial Group, LLC, doing business as CNAC (collectively, “JD

Byrider” or “Defendants’) pursuant to authority granted to the Attorney General by G.L.

c. 93A, § 4.! The Commonwealth seeks restitution, civil penalties, and reimbursement |

of its costs and expenses as remedies for JD Byrider’s purportedly unfair and deceptive ||

acts and practices in the sale of used cars to Massachusetts consumers.” :

The Commonwealth's claims against JD Byrider are set out in the three counts of its |

‘Complaint (°Complaint,” Docket Entry No. 1). Each claim focuses on certain, particular

automobile sales practices that the Commonwealth says JD Byrider employed in. |

violation of G.L. ¢. 934, § 2, and various Massachusetts consumer regulations. More - |!

specifically, Count | of the Complaint alleges, in relevant part, that JD Byrider made

certain “false and deceptive statements and omissions of fact in its advertising and

sales presentations’ to consumers, including purportedly false and deceptive

statements and omissions regarding the “sales price of JD Byrider's cars,” the “condition |

of JD Byrider’s cars,” and the “financing terms available.” Complaint, ff 92-93. Count il

of the Complaint alleges, in relevant part, that JD Byrider unfairly and deceptively

structured sales transactions with consumers that JD Byrider knew, or should have

known, were “doomed to fail,” including by “[alpproving loan applications where the

estimated budget [prepared by JD Byrider] shows consumers cannot or are not likely to

afford the required payments,” and by “[mJanipulating and/or underestimating consumer

expenses in the budget analysis [prepared by JD Byrider] to extend financing to |

consumers who otherwise would not qualify.” /d., $I 97-99. Count Il of the Complaint

alleges, in relevant part, that JD Byrider engaged in “oppressive or otherwise

unconscionable acts or practices” in selling used automobiles to consumers, including |

by “lojmitting and actively preventing consumers from learning the terms of the

+ GL. c. S3A, § 4, provides, in relevant part, that "[w]henever the attorney general has reason to believe

that any person is using or is about to use any method, act, or practice deciared by section two to be

Uniawl, and that proceedings would be in the public interest, he may bring an action in the name of the

‘commonwealth against such person...”

? Because it is undisputed that JD Byrider discontinued the acts and practices complained of by the

CCommorwealth at or around the time this action was commenced, the Commonwealth no longer seeks |

the injunctive relief that it previously prayed for in its Complaint.

financing and car price during the sales and application process,” and by “[mlaking false

of misleading statements during the closing ... related to consumers’ ability to afford the

loari and that JD Byrider's interest rates are competitive.” /d., | 104-105.

JD Byrider, for its part, does not contest that it previously engaged in certain of the

business practices that the Commonwealth complains of, but disputes that those

practices were in any way “unfair or deceptive.”

The case came before the Court most recently on the Commonwealth's Motion for

Partial Summary Judgment (the “Motion”). The Motion seeks summary judgment on the

issue of liability only as to Count Il of the Commonwealth's Complaint, which alleges

that JD Byrider unfairly and deceptively structured sales transactions with consumers

that it knew, or should have known, were “doomed to fail.” JD Byrider opposes the

Motion.

‘The Court conducted a hearing on the Commonwealth's Motion on December 11, 2019.

All parties appeared and argued. Upon consideration of the written submissions of the

parties and the oral arguments of counsel, the Commonwealth's Motion is ALLOWED

for the reasons summarized, briefly, below.

Factual Background

The following material facts, as revealed by the summary judgment record, are

effectively undisputed.®

JD Byrider is a “Buy Here Pay Here” used car dealership with three Massachusetts

locations in Brockton, Dartmouth, and Springfield. SOM, {ff 1, 6. It is a franchisee of

Indiana-based Byrider Franchising, LLC. Id. ] 9. JD Byrider previously operated

another sales location in the Dorchester section of Boston that closed in November

2018. {d., 17. JD Byrider is known as a “Buy Here Pay Here” dealership because it

provides financing for the cars that it sells through its in-house lender, CNAC. /d.,

M12, 5. Since 2011, not a single customer has purchased a vehicle from JD Byrider for

cash. /d., 14. Instead, during this time period, customers have purchased cars from

the company exclusively by means of financing offered through CNAC, which takes the

form of a'written retail installment sale contract ("RISC"). /d., 15.

During the relevant time period (prior to approximately October 2017, hereinafter the:

“Relevant Time Period”), virtually all of vehicles offered for sale by JD Byrider had an

identical sales price of approximately $12,000, regardless of age or condition. /d., 14.

According to JD Byrider Vice-President Trevor Wiggins, ‘lelverything [was] very ,

uniform.” Id, JD Byrider provided financing to its customers, through CNAC, at a fixed,

*° The undisputed facts recited herein generally are taken from the Consolidated Statement of Materials

Facts ("SON") filed in conjunction with the Commonwealth's Motion,

fou

non-negotiable interest rate of 19.95%. /d.,]20. All JD Byrider consumers receive the

same 19.95% interest rate, regardless of their credit score. /d., [21.

From January 1, 2011 through February 2, 2016, JD Byrider paid an average of $4,863

to acquire the vehicles it sold to consumers, /d., 1] 33. ‘The vehicles sold by JD Byrider

during this time period had been driven an average of 98,913 miles. Id. 1134.

JD Byrider engaged in several different forms of advertising to consumers during the

Relevant Time Period. JD Byrider's television advertisements prominently mentioned

“affordable payments,” and represented that “[olur goal is to get you on the road and |

keep you there affordably." /d., ff] 42-43. JD Byrider also operates a website,

www.jdbyrider.com. During the Relevant Time Period, JD Byrider’s website promised

that “[wJe always make sure your budget will fit your car payment before you sign the

paperwork, so you can feel confident you can succeed.” /d., {| 48. As of March 2016,

JD Byrider’s website also stated that the affordable payments offered by JD Byrider “are

based on your lifestyle so they'll fit into your budget.” Id., .47.

JD Byrider also sent promotional e-mails to consumers during the Relevant Time

Period. /d., [ 48. JD Byrider's promotional e-mails included statements such as

“Affordable Payments: We review your budget with our exclusive lender, CAC, in order

to customize an affordable payment " and “[t]he next step ... is a meeting in which we

prepare a thorough budget analysis and you make your selection from our inventory.”

id., 49. In other public facing documents and in its internal policies, JD Byrider further

‘stated that it only closed deals “that are affordable and that are designed for customer

success.” /d., 1140.

In selling cars to consumers during the Relevant Time Period, JD Byrider sales

representatives used a standardized sales process. /d., | 50. JD Byrider’s standard

sales process included an introductory sales presentation to each prospective customer

using a flip chart that introduced the customer to JD Byrider’s car sales, financing, and

service contract program (the “Flip Chart’). /d., | 51. JD Byrider’s Flip Chart was

designed for an A-frame stand, with one page facing the consumer and the other facing

the sales representative. Jd., 52. JD Byrider expected its sales representatives to

present every page of the Flip Chart to a prospective customer. /d., | 53. Prior to

February 2018, the Flip Chart represented that JD Byrider provided "A Better Car, An

Affordable Payment and Better Car Care.” /d., | 53. The Flip Chart also represented

that ‘[iIn house financing representatives from CNAC work to get you affordable initial

and ongoing payments.” /d., | 56.

The sales representative's side of the JD Byrider Flip Chart set out a number of scripted

“sales probes” that the sales representative could use while conversing with a

Prospective customer. /d., 57. Prior to February 2018, the sales probe regarding

3

“Affordable Payments” prompted sales representatives to tell customers that “[wJe make

sure your payments are affordable, or we don't do the deal,” and “[wJe work on your ,

budget and we can approve you right here." Id., 160.

During the Relevant Time Period, JD Byrider conducted a customer “budget analysis”

{the “Budget Analysis) in connection with every RISC.* Id., ] 62. In conducting the

Budget Analysis, JD Byrider interviewed the consumer and reviewed any associated

Paperwork. /d., | 63. JD Byrider purportedly used the Budget Analysis to determine

whether the consumer could afford the payments on the used motor vehicle that he/she °

intended to purchase from JD Byrider. /d., {] 64. -In order to complete each Budget

Analysis, JD Byrider used the "Discover System," a software program, to input

information directly into the Budget Analysis form. /d,, 467. The Budget Analysis form

compared the consumer's net income to his or her expenses and to calculate the ratio

of the consumer's “Expenses to Income” (‘ETI’). Id. | 68. To pass the Budget

Analysis, a consumer's ETI supposedly had to be less than 100%, meaning that the

consumer's income had to exceed the consumer's expenses. /d., | 69. JD Byrider

obtained a consumer's credit report as part of the finance underwriting process, but it

did not consider the consumer's credit score in deciding whether to approve him or her

forfinancing. Id., 173.

JD Byrider's Budget Analysis did not, in fact, accurately assess a consumer's ability to

afford the payments on a motor vehicle purchased from JD Byrider. The Budget .

Analysis form included fields for the anticipated JD Byrider car payment, as well as the

consumer's household expenses, including rent or mortgage payments, groceries,

clothing, hobbies, and other expenses. /d.,{]74. The Budget Analysis also had a field

for the consumer's monthly net, take-home income. /d., 175. The Discover System,

however, auto-populated preset values for certain expenses on the Budget Analysis

form (the “Preset Expenses"), /d., | 77. Preset Expenses included groceries, the

anticipated car payment, gas and auto repairs, and clothing. /d.,{]78. These expenses

were “hard-coded” into the Discover System, meaning that the numbers used in the

Budget Analysis did not vary regardless of the consumer's actual expenses for these

items. id., 177. JD Byrider never conducted a survey to determine how the expenses

that were hard-coded into the Discover System compared to the average cost for these

items in Massachusetts. id, 181.

For example, the Preset Expense in the Discover System for groceries was only $100

per month, per person in the household. /d., {| 85. This amount was less than one-third

of the actual single person food expense for U.S. households as calculated by the U.S.

Bureau of Labor Statistics ("BLS") as of 2017. /d., 91. Similarly, the Preset Expense

* Use of the Budget Analysis is one of the sales practices that JD Byrider discontinued shortly after this

action was filed in September 2017.

4

in the Discover System for clothing was between $43 to $45 per month for each

prospective borrower on the RISC agreement. /d., {| 93-94. This amount was

approximately one-half of the actual single person clothing expense for U.S. households

as calculated by the BLS as of 2017. Id., 195.

JD Byrider's Budget Analysis also excluded entire categories of typical consumer

expenses. /d., 1104. For example, the Budget Analysis form did not include expense

fields for laundry expenses, tax payments, or home maintenance or repairs. /d., {] 105.

See also Joint Appendix, Exhibit 2 to Exhibit C at JDB0004688 (sample Budget Analysis |

form). JD Byrider's Budget Analysis also ignored the consumer's other debts, such as

outstanding student loans or credit card debts, if the consumer reported to JD Byrider

that he or she was not making payments on those obligations. SOM, ffl 106-107.

When a.JD Byrider customer proved unable to make his or her required monthly car

payments, the customer's car usually was repossessed by, or voluntarily surrendered

to, JD Byrider. /d., 1 135. According to JD Byrider, involuntary repossessions and

voluntary surrenders accounted for 27.1% of the RISC contracts issued by JD Byrider in

2013; 27.1% of the RISC contracts issued by JD Byrider in 2014; and 27.7% of the

RISC contracts issued by JD Byrider in 2015. /d. Of the 5,724 cars that JD Byrider sold

in Massachusetts between 2013 and 2016, 1,478 subsequently were repossessed by,

or voluntarily surrendered to, JD Byrider. /d., W].137-140. JD Byrider subsequently

resold a number of the repossessed or returned vehicles to other consumers. Id.,

1144.

Discussion

‘Summary judgment is appropriate when, viewing’ the evidence in the light most

favorable to the non-moving party, there is no genuine issue of material fact and the

moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c); Cargill,

Inc. v. Beaver Coal & Oil Co., 424 Mass. 356, 358 (1997). A party who does not bear

the burden of proof at trial may demonstrate the absence of a genuine issue of material

fact either by submitting affirmative evidence negating an essential element of the

nonmoving party's case, or by showing that the non-moving party has no reasonable

expectation of proving an essential element of his or her case at trial. See

Kourouvacilis v. General Motors Corp., 410 Mass. 706, 716 (1991).

‘The Commonwealth argues that it is entitled to summary judgment in its favor as to JD

Byrider's liability on Count Il, which alleges that JD Byrider, during the Relevant Time

Period, violated G.L. c. 934, § 2, by structuring sales transactions with consumers that

JD Byrider knew, or should have known, were “doomed to fail.” Specifically, the

Commonwealth asserts that JD Byrider affirmatively represented through its advertising

and sales presentations to consumers that it only entered into sales transactions that

5

were “affordable” and “designed for customer success,” while its allegedly unfair and

deceptive sales practices, including its use of the questionable Budget Analysis, caused

many consumers to agree to purchase motor vehicles that were beyond their means.

This conduct, the Commonwealth argues, violated G.L. c, 93A, § 2, as a matter of law.

The Court agrees.

General Laws c. 93A, § 2(a), makes unlawful any “unfair or deceptive acts or practices |

in the conduct of any trade or commerce” in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The |

statute's purpose is “to improve the commercial relationship between consumers and |:

business persons and to encourage more equitable behavior in the marketplace by

imposfing] liability on persons seeking to profit from unfair practices.” Herman v. Admit |!

One Ticket Agency LLC, 454 Mass. 611, 615 (2009) (citation and internal quotation

marks omitted). Chapter 93A creates new substantive rights, and in particular cases,

“makfes] conduct unlawful which was not unlawful under the common law or any prior

statute.” Kattar v. Demoulas, 433 Mass. 1, 12 (2000) ("Kattar’), quoting Commonwealth

v, DeCotis, 366 Mass, 234, 244 n.8 (1974),

The provisions of G.L, c. 93A do not define precisely what conduct qualifies as “unfair or

deceptive.” The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ("SJC”), however, has

‘observed that “[{Jhere is no limit to human inventiveness in this field.” Kattar, 433 :,

Mass. at 13, quoting Levings v. Forbes & Wallace, inc., 8 Mass. App. Ct. 498, 503

(1979). What is “unfair or deceptive” depends on “the particular circumstances and

context in which the term is applied." Commonwealth v. Fremont Inv, & Loan, 452

Mass. 733, 743 (2008) (‘Fremont’). As a general matter, a practice can be considered

“unfair or deceptive” if it is “within at least the penumbra of some common-law, |

statutory, or other established concept of unfairness.” PMP Assocs., Inc. v. Globe

Newspaper Co., 366 Mass. 593, 596 (1975). In the advertising context, a statement or

tepresentation is “deceptive” if it “has the capacity to. mislead consumers, acting

Teasonably under the circumstances, to act differently from the way they otherwise

would have acted (i.e., to entice a reasonable consumer to purchase the product).”

Aspinall v. Phillip Morris Cos., 442 Mass. 381, 396 '(2004) (“Aspinal’). A ruling that

particular conduct violates G.L. c..93A "is a legal, not a factual, determination.” R.W.

Granger & Sons v. J & S Insulation, Inc., 435 Mass. 66, 73 (2001).

In this case, the Court has no difficulty concluding from the undisputed summary

judgment record that JD Byrider violated G.L. ¢. 93A, § 2, during the Relevant Time °

Period, by falsely representing to consumers that it only entered into sales transactions ,

that were “affordable” and “designed for customer success,” when the true

circumstances were quite different. It is clear from the evidence that JD Byrider's

deeply-flawed Budget Analysis did not, and could not, reasonably be expected to

provide either JD Byrider or the customer with an accurate assessment of the

customer's financial ability to purchase a motor vehicle from JD Byrider. The inputs to

6-

|

r

that Budget Analysis frequently bore little relation to the customer's actual financial

situation, which had the effect of rendering the output highly unreliable. JD Byrider

nonetheless used its Budget Analysis as a sales tool to persuade customers who

objectively lacked the necessary resources to go forward with their purchases even

though JD Byrider knew, or should have known, that such customers had a high risk of

defaulting on the required loan payments. The SJC has expressly held, in analogous

circumstances, that such conduct can consfitute an unfair act that is prohibited by G.L.

¢. 9A, See Fremont, 452 Mass. at 748-749 (‘the origination of a home mortgage loan

that the lender should recognize at the outset the borrower is not likely to be able to

repay’ found to be a violation of G.L. c. 93A). See also Drakopoulos v. U.S, Bank Nat’!

Ass'n, 465 Mass. 775, 786 (2013) (clarifying that “[tJhe holding of Fremont was that

IG.L. c.] 93A prohibits the origination of a home mortgage loan that the lender should

recognize at the outset that the borrower is not likely to be able to repay’) (citations and

internal quotation marks omitted).

‘The Court accordingly rules that, although JD Byrider stopped using its Budget Analysis

in October 2017, its sales practices prior to that date, as complained of in Count Il of the

Commonwealth's Complaint, undeniably “ha[d] the capacity to mislead consumers” in

their decisions to purchase used motor vehicles from JD Byrider and, therefore, violated

GL. c. 93, § 2.5 Aspinall, 442 Mass. at 396.

* In making this ruling, the Court has considered and expressly rejects JD Byrider’s argument that entry

‘of summary judgment on Count Il of the Commonwealth's Complaint is inappropriate because JD Byrider

has disputed “almost five dozen” of the facts contained in the parties’ Statement of Facts. See

Defendants’ Opposition to Plaintiff's Motion for Partial Summary Judgment (‘Defendants' Opp”) at 6. AS

explained above, the undisputed material facts ‘matter are more than sufficient to support the

Court's ruling. See Beatty v. NP Corp., 31 Mass. App. Ct. 606, 607 (1991) (“That some facts are in

dispute will not necessarily defeat a motion for summary judgment. The point is that the disputed issue of

fact must be materia”)

‘The Court similarly has considered and rejects JD Byrider’s further argument that the entry of summary

Judgment on Count I! is inappropriate because the Commonwealth has “failled] to establish causation or

proximate causation” linking JD Byrider’s unfair or deceptive conduct with any actual consumer losses.

‘See Defendants’ Opp. at 11-13. Proof of causation or loss is not an element of a claim by the Attorney

General under G.L. ¢. 934, § 4, See Commonwealth v. Fall River Motor Sales, Inc., 409 Mass. 302, 312 °

(1991) (noting in action under G.L. c. 93A, § 4, alleging misleading advertising practices by automobile

dealership, that “fhe violation, by definition, caused injury to the public, and there was no need for the

judge to have, or to consider, proof of any actual or specific injury’).

ayy

Order

For the foregoing reasons, IT IS HEREBY ORDERED that the Commonwealth's Motion

for Partial Summary Judgment (Docket Entry No. 19) is ALLOWED. Judgment Shall |

enter in favor of the Commonwealth on Count il of its Complaint on the issue of labilty \

only.

ea

Brian A/Davis

Associate Justice of the Superior Court |

Date: January 17, 2020

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- USDA Responses To Senator Richard Blumenthal Re Beulah and KarenDocumento3 pagineUSDA Responses To Senator Richard Blumenthal Re Beulah and KarenJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- New Valley Bank & Trust Public Co. FileDocumento91 pagineNew Valley Bank & Trust Public Co. FileJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Acute Hospital Health System Financial Performance Report - 2019Documento32 pagineAcute Hospital Health System Financial Performance Report - 2019Jim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Massachusetts To Help Homeowners With Crumbling FoundationsDocumento8 pagineMassachusetts To Help Homeowners With Crumbling FoundationsJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Hotel JessDocumento2 pagineHotel JessJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- 2020 MassTrails Grant AwardsDocumento9 pagine2020 MassTrails Grant AwardsJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- MBTA Procurement For 80 Bi-Level Commuter Rial CarsDocumento16 pagineMBTA Procurement For 80 Bi-Level Commuter Rial CarsJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Victims' Suit Against Bill Cosby Stays Alive As Comedian Serves Prison Sentence in PennsylvaniaDocumento2 pagineVictims' Suit Against Bill Cosby Stays Alive As Comedian Serves Prison Sentence in PennsylvaniaJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- March 19 Presentation Final 3 19 19 PDFDocumento72 pagineMarch 19 Presentation Final 3 19 19 PDFJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Amtrak Valley Flyer ScheduleDocumento1 paginaAmtrak Valley Flyer ScheduleJim Kinney100% (1)

- American Outdoor Brands Report To Shareholders On Gun SafetyDocumento26 pagineAmerican Outdoor Brands Report To Shareholders On Gun SafetyJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Applied Golf Solar Project at Hickory Ridge in AmherstDocumento118 pagineApplied Golf Solar Project at Hickory Ridge in AmherstJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Security Cola Facts 2019Documento2 pagineSocial Security Cola Facts 2019Jim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- MassMutual Puts Enfield Campus On The MarketDocumento14 pagineMassMutual Puts Enfield Campus On The MarketJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Springfield Default Letter To SilverBrickDocumento3 pagineSpringfield Default Letter To SilverBrickJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- CISA 2018 Farm Products GuideDocumento92 pagineCISA 2018 Farm Products GuideJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Enfield Square Mall Deed DocumentDocumento14 pagineEnfield Square Mall Deed DocumentJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Public Response To Interstate 91 PlansDocumento26 paginePublic Response To Interstate 91 PlansJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Interstate 91 Meeting PresentationDocumento35 pagineInterstate 91 Meeting PresentationJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- CTRAIL ScheduleDocumento2 pagineCTRAIL ScheduleJim Kinney100% (1)

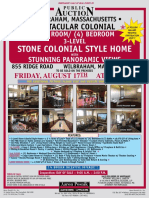

- Wilbraham AuctionDocumento2 pagineWilbraham AuctionJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Auction at 274-276 High StreetDocumento2 pagineAuction at 274-276 High StreetJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Saratoga Race Course MapDocumento1 paginaSaratoga Race Course MapJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Hartford Springfield Line ScheduleDocumento2 pagineHartford Springfield Line ScheduleJim KinneyNessuna valutazione finora