Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Yeats Symbolism of Poetry

Caricato da

Yudi UtomoDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Yeats Symbolism of Poetry

Caricato da

Yudi UtomoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Dr.

Richard Clarke LITS3001 Notes Week 04

1

W. B. YEATS “THE SYMBOLISM OF POETRY” (1900)

Here, the Modernist poet and theorist Yeats continues very much in the vein of Coleridge, Shelley and

company by arguing that poetry calls “into outer life some portion of the divine life, or of the buried

reality” (31). The realist trend in literature – which is the product of what Yeats calls the “scientific

movement” (31) – encouraged, in his view, a form of literature “always tending to lose itself in

externalities of all kinds” and resulting in what he terms “picturesque writing, in word-painting” (31).

However, there is another tendency in literature, the propensity to “dwell upon the element of evocation,

of suggestion, upon what we call the symbolism in great writers” (31) which he perfected in his own

poetry.

Yeats explains symbols as follows:

All sounds, all colours, all forms, either because of their preordained energies or

because of long association, evoke indefinable and yet precise emotions, or, as I prefer

to think, call down among us certain disembodied powers, whose footsteps over our

hearts we call emotions. (33)

Poetry, like art, has its origin in these lofty emotions even as it has an emotional effect upon its reader:

poets, he writes, “are continually making and unmaking mankind” (33). Indeed, every concrete affair or

achievement has its origin also in emotion: “all those things that seem useful or strong, armies, moving

wheels, modes of architecture” (33), etc. are the product of “some mind long ago” (33) which “had . . .

given itself to some emotion . . . and shaped sounds or colours or forms, or all of these, into a musical

relation, that their emotion might live in other minds” (33). In short, emotion is not the effect of life, it is

the source of all life and achievement. Yeats doubts whether the “crude circumstance of the world,

which seems to create all our emotions, does more than reflect, as in multiplying mirrors, the emotions

that have come to solitary men in moments of poetical contemplation” (33-34). The reason for this is

that “unless we believe that outer things are the reality, we must believe that the gross is the shadow of

the subtle” (34).

This view of poetry leads Yeats to suggest that there is need for a corresponding “manner” (34)

of poetry, a

return to the way of our fathers, a casting out of descriptions of nature for the sake of

nature, of the moral law for the sake of the moral law, a casting out of all anecdotes and

of . . . brooding over scientific opinion . . . and of that vehemence that would make us do

or not do certain things. (34)

Yeats also advocates the casting out of “those energetic rhythms, as of a man running, which are the

invention of the will with its eyes always on something to be done or undone” (34) and their replacement

by “wavering, meditative, organic rhythms, which are the embodiment of the imagination, that neither

desires nor hates because it has done with time, and only wishes to gaze upon some reality, some

beauty” (34).

In short, a “change of style” (34) in this way is the result of a “change in substance” (34) and a

“return to imagination” (34), that is, to the “understanding that the laws of art, which are the hidden laws

of the world, can alone bind the imagination” (34). Acknowledging this would make it impossible for

anyone to “deny the importance of form . . . for although you can expound an opinion, or describe a

thing, when your words are not quite well chosen, you cannot give a body to something that moves

beyond the senses, unless your words are as subtle, as complex, as full of mysterious life, as the body of

a flower or of a woman” (34). Great poetry crafted in this way possesses “perfections that escape

analysis, . . . subtleties that have a new meaning every day” (35).

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Clavis or Key To The Magic of SolomonDocumento455 pagineThe Clavis or Key To The Magic of SolomonAmy Castro94% (100)

- James Buhler, David Neumeyer, and Rob Deemer. Hearing The Movies: Music and Sound in Film HistoryDocumento3 pagineJames Buhler, David Neumeyer, and Rob Deemer. Hearing The Movies: Music and Sound in Film Historyelpidio5950% (6)

- Top 20 Figures of Speech - ..Documento7 pagineTop 20 Figures of Speech - ..Anup SawNessuna valutazione finora

- English AssignmentDocumento4 pagineEnglish AssignmentHaseeb MalikNessuna valutazione finora

- Morrigan Legendary MonsterDocumento4 pagineMorrigan Legendary MonsterBenNessuna valutazione finora

- A Study On Wolfgang IserDocumento7 pagineA Study On Wolfgang IserClaudia Javier MendezNessuna valutazione finora

- Directing Great Television Sample PDFDocumento34 pagineDirecting Great Television Sample PDFMichael Wiese Productions100% (3)

- Sons and Lovers PDFDocumento4 pagineSons and Lovers PDFHarinder Singh HundalNessuna valutazione finora

- Allegorical Stone Raft': Introduction: IberianismDocumento13 pagineAllegorical Stone Raft': Introduction: IberianismYashika ZutshiNessuna valutazione finora

- Novel EmmaDocumento15 pagineNovel Emmamariyamtariq53Nessuna valutazione finora

- Henrik IbsenDocumento3 pagineHenrik IbsenNimra SafdarNessuna valutazione finora

- Latin American LiteratureDocumento40 pagineLatin American LiteratureIrene TagalogNessuna valutazione finora

- Presentation About Chapter 1 - The Empire Writes Back With QuestionsDocumento21 paginePresentation About Chapter 1 - The Empire Writes Back With Questionscamila albornoz100% (1)

- The Leading Ladies of The French LieutenantDocumento29 pagineThe Leading Ladies of The French LieutenantAlina Cuteanu bNessuna valutazione finora

- Metaphysical Poets: George Herbert Go To Guide On George Herbert's Poetry Back To TopDocumento10 pagineMetaphysical Poets: George Herbert Go To Guide On George Herbert's Poetry Back To TopEya Brahem100% (1)

- Post-Structuralism: Mark Lester B. LamanDocumento14 paginePost-Structuralism: Mark Lester B. LamanMark Lester LamanNessuna valutazione finora

- 04 Modernism Definition and TheoryDocumento2 pagine04 Modernism Definition and TheoryMaria CarabajalNessuna valutazione finora

- Modernism and Post Modernism in LiteratureDocumento16 pagineModernism and Post Modernism in LiteratureHanieh RostamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Themes of American PoetryDocumento2 pagineThemes of American PoetryHajra ZahidNessuna valutazione finora

- Features of Inter-War YearsDocumento6 pagineFeatures of Inter-War Yearsrathodvruti83Nessuna valutazione finora

- Dollimore Cultural MaterialismDocumento24 pagineDollimore Cultural MaterialismMahnoor Imran100% (1)

- POEMS Eliot, TS Portrait of A Lady (1917) Analysis by 3 Critics PDFDocumento3 paginePOEMS Eliot, TS Portrait of A Lady (1917) Analysis by 3 Critics PDFKasun PrabhathNessuna valutazione finora

- History of Translation and Translators 1Documento7 pagineHistory of Translation and Translators 1Patatas SayoteNessuna valutazione finora

- T.S Eliot Life and WorksDocumento3 pagineT.S Eliot Life and WorksLavenzel YbanezNessuna valutazione finora

- ENGL 3312 Middlemarch - Notes Part IDocumento4 pagineENGL 3312 Middlemarch - Notes Part IMorgan TG100% (1)

- The Deconstructive AngelDocumento3 pagineThe Deconstructive Angelgandhimathi2013100% (1)

- Reader Response To AustenDocumento7 pagineReader Response To AustenMustapha AlmustaphaNessuna valutazione finora

- Russian Formalism - Any CarolDocumento5 pagineRussian Formalism - Any CarolOmega ZeroNessuna valutazione finora

- Oxford Reference: Critical TheoryDocumento3 pagineOxford Reference: Critical TheoryRuben MeijerinkNessuna valutazione finora

- Sem IV - Critical Theories - General TopicsDocumento24 pagineSem IV - Critical Theories - General TopicsHarshraj SalvitthalNessuna valutazione finora

- A Study of Socio-Political Manipulation in Bhisham Sahni's TamasDocumento6 pagineA Study of Socio-Political Manipulation in Bhisham Sahni's TamasIJELS Research JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- The Myth of The Middle ClassDocumento11 pagineThe Myth of The Middle Classrjcebik4146Nessuna valutazione finora

- Bege 108 PDFDocumento6 pagineBege 108 PDFFirdosh Khan86% (7)

- H ThesisDocumento87 pagineH ThesisRenata GeorgescuNessuna valutazione finora

- AssignmentDocumento4 pagineAssignmentDivya KhasaNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary BastiDocumento10 pagineSummary BastiMayankNessuna valutazione finora

- Twentieth Century Literature Main Features of 20th Century Literature (Literary Creativity of 20th Century England.)Documento8 pagineTwentieth Century Literature Main Features of 20th Century Literature (Literary Creativity of 20th Century England.)Kusum KafleNessuna valutazione finora

- The Price of Plot in Aristotle's PoeticsDocumento9 pagineThe Price of Plot in Aristotle's PoeticscurupiradigitalNessuna valutazione finora

- A Postmodernist Analysis of A.K. Ramanujan's PoemsDocumento8 pagineA Postmodernist Analysis of A.K. Ramanujan's PoemsHamzahNessuna valutazione finora

- The Blues I M Playing Literary Analysis 1Documento6 pagineThe Blues I M Playing Literary Analysis 1api-575510166100% (1)

- Neo-Classicism, Pope, DrydenDocumento9 pagineNeo-Classicism, Pope, DrydenyasbsNessuna valutazione finora

- In Memoriam3443Documento6 pagineIn Memoriam3443Ton TonNessuna valutazione finora

- S. Sulochana Rengachari - T S Eliot - Hamlet and His Problems - An Analysis-Prakash Book Depot (2013)Documento50 pagineS. Sulochana Rengachari - T S Eliot - Hamlet and His Problems - An Analysis-Prakash Book Depot (2013)pallavi desaiNessuna valutazione finora

- The Life of Virginia WoolfDocumento12 pagineThe Life of Virginia Woolfapi-255619968Nessuna valutazione finora

- 1 20th Century LiteratureDocumento77 pagine1 20th Century LiteratureIonut TomaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mulk Raj Anand Wikipedia PDFDocumento4 pagineMulk Raj Anand Wikipedia PDFSaim imtiyazNessuna valutazione finora

- WILLIAM K and Beardsley IntroDocumento6 pagineWILLIAM K and Beardsley IntroShweta SoodNessuna valutazione finora

- Passage To IndiaDocumento12 paginePassage To IndiaArnavBhattacharyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lyotard!Documento2 pagineLyotard!NoemiCoccoNessuna valutazione finora

- PoetryDocumento5 paginePoetryIrfan SahitoNessuna valutazione finora

- What Does Macherey Mean by The Unconscious' of The Work? How Can A Text Have An Unconscious?Documento7 pagineWhat Does Macherey Mean by The Unconscious' of The Work? How Can A Text Have An Unconscious?hollyoneill1992Nessuna valutazione finora

- John DrydenDocumento17 pagineJohn DrydenMai RajabarNessuna valutazione finora

- Concept of Hybridity and Transculturalism ModernityDocumento5 pagineConcept of Hybridity and Transculturalism ModernityVaishnavi ChaudhariNessuna valutazione finora

- Modernism, PM, Feminism & IntertextualityDocumento8 pagineModernism, PM, Feminism & IntertextualityhashemfamilymemberNessuna valutazione finora

- The Post-Modern Fracturing of Narrative Unity Discontinuity and Irony What Is Post-Modernism?Documento2 pagineThe Post-Modern Fracturing of Narrative Unity Discontinuity and Irony What Is Post-Modernism?hazelakiko torresNessuna valutazione finora

- The Theme of The Country and The City in PDFDocumento4 pagineThe Theme of The Country and The City in PDFROUSHAN SINGHNessuna valutazione finora

- Beppo Is Byron's First Poem Written in Ottava Rima - An Italian Stanza of 8 Iambic PentameterDocumento3 pagineBeppo Is Byron's First Poem Written in Ottava Rima - An Italian Stanza of 8 Iambic Pentameterapi-27180477Nessuna valutazione finora

- Life and Work in Shakespeare's PoemsDocumento36 pagineLife and Work in Shakespeare's PoemsshivnairNessuna valutazione finora

- Pablo Neruda, The Chronicler of All Things - Jaime AlazrakerDocumento7 paginePablo Neruda, The Chronicler of All Things - Jaime AlazrakeraarajahanNessuna valutazione finora

- SocioDocumento24 pagineSocioGovt. Tariq H/S LHR CANT LAHORE CANTTNessuna valutazione finora

- BeautifulyoungnymphDocumento14 pagineBeautifulyoungnymphapi-242944654Nessuna valutazione finora

- An Analysis of Romanticism in The Lyrics ofDocumento10 pagineAn Analysis of Romanticism in The Lyrics ofRisky LeihituNessuna valutazione finora

- Mohsin HamidDocumento15 pagineMohsin HamidRai Younas BoranaNessuna valutazione finora

- Criticism and CreativityDocumento19 pagineCriticism and CreativityNoor ZamanNessuna valutazione finora

- Schools PDFDocumento8 pagineSchools PDFSayed AbuzeidNessuna valutazione finora

- A Study Guide for John Keats's "Bright Star! Would I Were Steadfast as Thou Art"Da EverandA Study Guide for John Keats's "Bright Star! Would I Were Steadfast as Thou Art"Nessuna valutazione finora

- Market Leader Upper Intermediate Teacher S BookDocumento120 pagineMarket Leader Upper Intermediate Teacher S Bookaustria198169% (85)

- To Kill A Mockingbird - Chapters 1-4 QuizDocumento3 pagineTo Kill A Mockingbird - Chapters 1-4 QuizFiona O ConnorNessuna valutazione finora

- LANG, Ariella Lang - Converting A Nation - A Modern InquisitionDocumento248 pagineLANG, Ariella Lang - Converting A Nation - A Modern InquisitionJorge Miguel AcostaNessuna valutazione finora

- Analysis of Moral Values in The Short StoryDocumento13 pagineAnalysis of Moral Values in The Short StoryMba NovianaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bicho LimDocumento18 pagineBicho LimAbhijeet NaikNessuna valutazione finora

- The Wild West and The HimalayasDocumento12 pagineThe Wild West and The HimalayasJudith DevasahayamNessuna valutazione finora

- Spells ListDocumento32 pagineSpells ListVittorioNessuna valutazione finora

- THINK WORKBOOK 2 - Assets - Cambridge University Press - SelfHelpBooksDocumento1 paginaTHINK WORKBOOK 2 - Assets - Cambridge University Press - SelfHelpBooksBích Phương BùiNessuna valutazione finora

- English Art Integrated Project: Elementary School in A SlumDocumento16 pagineEnglish Art Integrated Project: Elementary School in A SlumShraddha KedarNessuna valutazione finora

- Tone Worksheet 3: Directions: Read Each Poem and Then Answer The Following Questions. NoonDocumento2 pagineTone Worksheet 3: Directions: Read Each Poem and Then Answer The Following Questions. NoonRoseNessuna valutazione finora

- A Study of Folklore Materials in The Novel Birgwsrini Thungri by Bidyasagar NarzaryDocumento10 pagineA Study of Folklore Materials in The Novel Birgwsrini Thungri by Bidyasagar NarzaryIJAR JOURNALNessuna valutazione finora

- Ppt. Intro To Esp. Language Variation and Register Analysis. Sem 4Documento14 paginePpt. Intro To Esp. Language Variation and Register Analysis. Sem 4Annastya SalsabilaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Canterbury Tales: Geoffrey ChaucerDocumento11 pagineThe Canterbury Tales: Geoffrey ChaucerMattia LauretanoNessuna valutazione finora

- CSC Rksheet Poetry Comprehension (S's Copy)Documento3 pagineCSC Rksheet Poetry Comprehension (S's Copy)4C (22) Yu Hoi ShuenNessuna valutazione finora

- Javított Verzió: Folyamatos MultDocumento2 pagineJavított Verzió: Folyamatos MultEuropean United Armed ForcesNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 8: Honey, You're Sleep-Walking AgainDocumento8 pagineUnit 8: Honey, You're Sleep-Walking Againhanafi officialNessuna valutazione finora

- EK2 PrepoznavanjeDocumento7 pagineEK2 PrepoznavanjeIvana MladenovicNessuna valutazione finora

- Virtual Existentialism: Meaning and Subjectivity in Virtual WorldsDocumento149 pagineVirtual Existentialism: Meaning and Subjectivity in Virtual WorldsInty ASNessuna valutazione finora

- 1Documento10 pagine1Leni WismayaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Canonical AuthorsDocumento73 pagineCanonical AuthorsMnM Vlog OfficialNessuna valutazione finora

- Pray For Us IcarusDocumento174 paginePray For Us IcarusSandra Leticia Menchaca TapiaNessuna valutazione finora

- TN Set English 79Documento14 pagineTN Set English 79Anand BabuNessuna valutazione finora

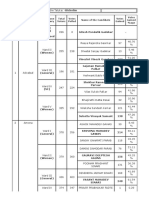

- SKF Shortlisted List 2022 BatchDocumento6 pagineSKF Shortlisted List 2022 Batchsai ChaitanyaNessuna valutazione finora

- DirectDocumento6 pagineDirectRoshaan AhmadNessuna valutazione finora