Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

IJRHAL - Phonaestheticism

Caricato da

Impact JournalsTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

IJRHAL - Phonaestheticism

Caricato da

Impact JournalsCopyright:

Formati disponibili

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in

Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL)

ISSN (P): 2347–4564; ISSN (E): 2321–8878

Vol. 7, Issue 11, Nov 2019, 59–68

© Impact Journals

PHONAESTHETICISM

Raj Kishor Singh

Central Department of English, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Nepal

Received: 21 Nov 2019 Accepted: 24 Nov 2019 Published: 30 Nov 2019

ABSTRACT

This paper discusses all about aesthetic aspects of phonetics in literary texts. Beautiful meanings and feelings are realized

with the use of phonetics in literary texts, both in prose and verse. Use of phonetics is to enhance beauty of a text. This has

been illustrated in this paper with the references of Ronald Carter & et al., J. R. Firth, and G. N. Leach.

KEYWORDS: Phonaesthetics, Phonetics, Aesthetics, Stylistics, Literature

INTRODUCTION

We are blessed with language and articulators organs that work easily and with flexibility with sonority in language.

Imagine, how could people have communicated information and shared feelings without language? We feel delighted when birds

chirp and twitter, when a river flows with murmurs, when wind blows with whisper, when trees whistle, and when mountains

smile. We feel frightened when thunder crashes, when lightening crashes, when dogs bark, when tigers roar, when waves beat the

lands, and when bamboo grove whistles at night. Even parents thunder at children. Children meow. Soldiers cow. This can be

possible only in natural, human language. Language is a wonderful tool of communication.

Signs, symbols and other aspects of languages are commonly used during communication. Verbal and non-verbal

communication applies semantic aspects of language. Words do not have meaning in isolation. Even dictionary meanings

are useless unless we use them in a context. Pragmatic meanings are much more preferable in linguistics. Phonetics adds

meanings to pragmatic and semantic aspects of language in a literary text.

David Crystal (1995) examines why people regard some words as inherently more beautiful than others. He says

that people ponder about the most beautiful words in English, in terms of sound rather than meaning. He defines the term

‘phonaesthetics’ as ‘the study of the expressive properties of sound’. He quotes some phonaesthetic words from Willard J.

Funk (lexicographer): tranquil, murmuring, mist, chimes, dawn, hush, tendril, rosemary, luminous, etc. Another list is from

poet John Kitching (poet): velvet, melody, young, gossamer, crystal, autumn, peace, mesmerism, blossom, etc. He also

presents a 1980s’ newspaper report, about an unnamed novelist who chooses peril, moon, shadow, carnation, heart, silence,

forlorn, April, apricot as beautiful words. He says that pleasant-sounding words have positive and desirable meanings.

Alma Denny, an American poet and columnist, writes the following poem with her phonaesthetic opinions,

Some words have such a lovely sound

It’s pleasant to roll them round and round

And savour their syllables on the tongue,-

Impact Factor(JCC): 4.8397 – This article can be downloaded from www.impactjournals.us

60 Raj Kishor Singh

Words like oriole, melody, young.

In the below poem, Denny opines with the same concept of phonaesthetic differences in words. Some words are

on our tongue and we like to pronounce them frequently because of their lovely and beautiful sounds. Some words have

ungraceful, harsh and abrasive letters but yet they have intrinsic beauty. Justifying Denny’s views, Crystal says that the

word peril can be a beautiful word though it sounds unusual.

Other words, though, of ungraceful letter,

Harsh, abrasive, sound even better!

These are words of intrinsic beauty,-

Service, conscience, kindliness, duty. (Crystal, 1995)

Phonology and Literary Texts

Phonetics and Phonology

Phonetics and phonology are the two fields dedicated to the study of human speech sounds and sound structures. The

difference between phonetics and phonology is that phonetics deals with the physical production of these sounds while

phonology is the study of sound patterns and their meanings both within and across languages.

Phonetics is strictly about audible sounds and the things that happen in your mouth, throat, nasal and sinus

cavities, and lungs to make those sounds. It has nothing to do with meaning. It’s only a description. For example, in order

to produce the word “bed”, you start out with your lips together. Then, air from your lungs is forced over your vocal

chords, which begin to vibrate and make noise. The air then escapes through your lips as they part suddenly, which results

in /b/ sound. Next, keeping your lips open, the middle of your tongue comes up so that the sides meet your back teeth while

the tip of your tongue stays down. All the while, air from your lungs is rushing out, and your vocal chords are vibrating.

There’s your /e/ sound. Finally, the tip of your tongue comes up to the hard palate just behind your teeth. This stops the

flow of air and results in /d/ sound as long as those vocal chords are still going. As literate, adult speakers of the English

language, we don’t need a physical description of everything required to make those three sounds. We simply understand

what to do in order to make them. Similarly, phoneticists simply understand that when they see /kæt/, it’s a description of

how most British and Americans pronounce the word “cat.” It’s not about meaning. It’s strictly physical. (O’Connor, 1992)

Phonology, on the other hand, is both physical and meaningful. It explores the differences between sounds that

change the meaning of an utterance. For example, the word “bet” is very similar to the word “bed” in terms of the physical

manifestation of sounds. The only difference is that, at the end of “bet,” the vocal chords stop vibrating so that sound is a

result only of the placement of the tongue behind the teeth and the flow of air. However, the meanings of the two words are

not related in the least. What a vast difference a muscle makes! This is the biggest distinction between phonetics and

phonology, although phonologists analyze a lot more than just the obvious differences. They also examine variations on

single letter pronunciations, words in which multiple variations can exist versus those in which variations are considered

incorrect, and the phonological “grammar” of languages. For a native speaker of English, he pronounces the letter /p/ three

different ways. He may not realize it, but he does, and if he were to hear the wrong pronunciation, he might not be able to

put his finger on the problem, but he would think it sounded really weird. Say the word “pop-up.” The first /p/ has more air

behind it than the others, the second is very similar to the first, but it doesn’t have much air in it, and the last one is barely

NAAS Rating: 3.10 – Articles can be sent to editor@impactjournals.us

Phonaestheticism 61

pronounced at all. The word ends there when your lips close. Now, say it again, but put a lot of air in the final /p/. That is

realized odd. That’s because the aspirated /p/ (with air) sound is not “grammatically” correct at the end of an English word.

Similarly, Spanish words do not begin with an /s/ sound followed by a consonant, which makes it very difficult for

Spanish-speakers who are learning English to say words like “school,” “speak” and “strict.” Phonologists study these

things. (O’Connor, 1992)

Unlike consonants, vowels do not have obstruction of the air stream while it flows through the mouth. Vowels

involve shaping of the air stream in its passage. They also involve criteria of manner and position of articulation. For

vowels, manner of articulation involves voicing, lip rounding or spreading, length and degree of muscular tension. Place of

articulation for vowels involve gross generalizations relative to the front and back of the mouth, as well as tongue and jaw's

height. Rising of the tongue is noticed for high, mid, and low vowels. There are twelve monophthongs and eight

diphthongs. The monophthongs are classified in terms of

• length / duration of production

• parts / place of the tongue

• height / raising of the tongue

• position of lips

• position of muscles.

Similarly, diphthongs are classified into

• rising diphthongs and

• Falling diphthongs.

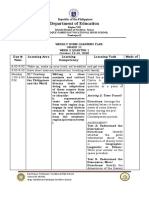

PLACE

MANNER

VOICING

Bilabial Labiodental Interdental Alveolar Palatal Velar Glottal

Voiceless p t k

Stop

Voiced b d g

Fricative

Voiceless f θ s h

Voiced v ð z

Voiceless

Affricate

Voiced

Nassal Voiced m n

Lateral Voiced

Rhotic Voiced r()

Glide Voiced

W j (w)

Source: My English Teacher.eu

Figure 1.

Impact Factor(JCC): 4.8397 – This article can be downloaded from www.impactjournals.us

62 Raj Kishor Singh

VOWELS

Front Central Back

Close i u

Close-mid e

Open-mid ε

æ

Open

Where symbols appear in pairs, the one

to the right represents a rounded vowel.

Source: Uni Bielefeld

Figure 2: Monophthongs.

Source: Slide Share

Figure 3: Diphthongs.

Phonology in Literary Texts

In literary texts, there are stylistic meanings along with the contextual meanings. Even phonology adds stylistic meaning to

a literary text. For example, Carter et al. analyses the phonological meanings in the following poem:

NAAS Rating: 3.10 – Articles can be sent to editor@impactjournals.us

Phonaestheticism 63

‘Meeting at Night’

Robert Browning

This poem has two stanzas. In the first stanza, the speaker is rowing his boat at night across the sea towards land. The

second stanza describes his journey across land and culminates in the lovers’ meeting at night.

The grey sea and long black land;

And the yellow half-moon large and low;

And the startled little waves that leap

In fiery ringlets from their sleep,

As I gain the cove with pushing prow,

And quench its speed i’ the slushy sand.

Then a mile of warm sea-scented beach;

Three fields to cross till a farm appears;

A tap at the pane, the quick sharp scratch

And blue spurt of a lighted match,

And a voice less loud, through its joys and fears,

Than the two hearts beating each to each!

While analyzing the major phonological sounds (consonants) in both stanzas, we can feel a good impact on the senses.

Consonants in the first stanza:

• The voiced lateral /l/, sometimes referred to as a 'liquid' and associated with the flowing, refers here to the rippling

qualities of water.

• The voiceless plosives /k/ and /p/ show soft percussive sounds.

• The voiceless fricatives /ʃ/ and /s/ show soft hissing sounds.

• The voiceless affricate /tʃ/ shows soft percussive sound, immediately followed by soft hissing sound.

These sounds, in the first stanza, suggest the action and sound of the oars. The plosives erect the vigorous moment of

the oars entering and pulling through the water and the fricatives are suggestive of the sound made by the disturbed water

after the oars are taken up ready for the next stroke.

In the second stanza, the narrator crosses the beach and fields to arrive at the farm. "A tap at the pane" echoes the

rhythm of his action and the voiceless plosives /t/ and /p/ suggest that his tapping is cautious and muted. (Carter et

al., 2002)

Firth and other linguists suggest that the meaning of a text "cannot be achieved at one fell swoop by analysis at

one level" (Firth, 1968: 192). Firth suggests that the meaning complex should be split up and that at each level the analyses

Impact Factor(JCC): 4.8397 – This article can be downloaded from www.impactjournals.us

64 Raj Kishor Singh

should try to capture specific types of meaning making mechanisms. "The accumulation of results at various levels adds up

to a considerable sum of partial meanings in terms of linguistics" (Firth, 1957/68: 197)

When we make statements of meanings in terms of linguistics, we may accept the language event as a whole and

then deal with it at various levels, sometimes in a descending order, beginning with social context and proceeding through

syntax and vocabulary or phonology and even phonetics, and at other times in the opposite order. (Firth, 1951/57: 192)

Phonological patterns are one of the ways "to mean" when creating texts. To illustrate the existence of

phonological meanings in texts, Firth presents an analysis of Lewis Carroll's famous nonsense poem called "Jabberwocky",

Firth discusses the poem and its phonological meanings in terms of its stanzas, specific rhymes and its phonematic

and prosodic processes. He concludes that the poem is certainly "English enough" in its realizations. (Firth, 1951 / 57: 195)

Crystal (1995) finds that continuants (/l, r, w, j/) are phonaesthetic sounds which compose beautiful words. Front

(notably labial) consonants are a little more frequent in phonaesthetically pleasing words, and back ones (velar and glottal)

a little less frequent in phonaesthetically pleasing words. Impression is that consonant clusters are an important feature of

phonaesthetic words but that is not true. They are not an important feature of phonaesthetic words. In Crystal’s words, a

word apparently sounds prettier if the manner of consonantal articulation changes as the syllables pass by. He argues that

people have an impression that long pure vowels are important in phonaesthetically pleasing words but he suggests that

four of the long vowels are not even in the top ten of the vowel list during his examination of the sounds. He says

diphthongs do better than those long sounds.

'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogroves,

And the mome raths ou'gabe.

Components of Literary Texts

For a thorough analysis of phonological meanings in texts, Firth (1951 / 57: 199) and Leach (1969:89-130) suggest many

components or elements of literary texts such as: alliteration (feel / fate), assonance (bead / eel), chiming of consonants

(foul and fair / mice and men), stress, intonation, reverse rhyme (send / sell), pararhyme (send / end), and onomatopoeia

(buzz). Such features can be distributed by a writer as to form part of artistic prosodies in both prose and verse. Firth

emphasizes that such phenomena in texts are not just "sound symbolism" or "onomatopoeia", but, rather, they are part of

the various means to express phonological meanings in texts, and thus they contribute to the total contextual meaning of

the texts. They create the prosodic mode of the text or the phonaesthetic character of the text.

Euphony (consonance) is for producing pleasant, rhythmical and harmonious effects. Cacophony (dissonance) is

for harsh, unpleasant, meaningless and discordant sounds.

Alliteration

Repetition of consonant sound in two or more than two words or accented Syllables is known as alliteration. This makes

sound of emphasis and interesting style. We can see it in this following piece:

NAAS Rating: 3.10 – Articles can be sent to editor@impactjournals.us

Phonaestheticism 65

A strong man struggling with the storms of fate.

Thomas Addison (quotation)

What is the 'alliteration' has been defined by Prof. Higgins in George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion (Act II)

Mrs. Pearce: Only this morning, sir, you applied it to your boots, to the butter, and to the brown bread.

Higgins: Oh, that ! Mere alliteration, Mrs. Pearce, natural to a poet.

Assonance

Repetition of vowel sound in two or more than two words or accented (stressed) syllables is known as assonance. It

demands that the sound similarity occurs within the vowels, not the consonants, and only in accented syllables: as lake and

fate.

Rhyme

In case of rhyme, similar sound is in the accented syllables of two or more words but the preceding consonants are

different as: cat and fat, but not meat and meat. Rhymes are classified as end rhymes, internal rhyme and beginning rhyme.

Rhyme scheme is determined by end rhymes as in the following (abab rhyme scheme):

There was a sound of revelry by right, a

And Belgium's Capital had gathered than b

Her beauty and her chivalry, and bright a

The lamps shore over fair women and bravemen b

Lord Byron (The Wave of Waterloo)

Stress

Stress is used for greater force, with greater effort, than the other syllables. For example, the sentence ‘I could hardly

believe my eyes’ has the words ‘hardly’, ‘believe’ and ‘eyes’ are stressed. Stress is important for many components in

literary texts. (O’Connor, 1992)

Metre is formal rhythm in lines of verse. The verse line is divided into feet which contain different rhythms and stresses.

The commonest English metre is the iambic feet. Metric feet are iambic (U-), trochaic (-U), anapestic (UU-) and dectylic (-UU). -

is spondee (stressed) and U is pyrrhic (unstressed). The number of feet are monometre (one), diametre (two), trimeter (three),

tetrameter (four), pentameter (five), hexameter (six), heptameter (seven) and octameter (eight), For example:

U — U— U — U — U —

B u t W h en t o m isch i ef m ort a ls b e nd th e ir w ill.

U — U — U — U — U —

H o w soon th e y f in d f i t in st u ments o f i II !

Alexander Pope (The Rape of the Lock)

Verse in iambic pentameter without rhyme is blank verse. Each line has ten syllables. The second, fourth, eighth and tenth

syllables bear the accents (stress) which is known as pentameter. Now this term includes almost any material unrhymed

Impact Factor(JCC): 4.8397 – This article can be downloaded from www.impactjournals.us

66 Raj Kishor Singh

form. 'U' is unaccented and '-' is accented.

— U — U — U — U —

good | Old man | h o w well | i n thee a ppea rs |

U – U — U — U— U —

Th e e con | st a nt se r | v i ce of | th e an|t i que wor ld |

William Shakespeare (As You Like It, Act 2, Scene 3)

Intonation

Intonation is good for rhythm and music. It is also good for rhetoric. Intonation refers to the voice going up and down and

the different notes of the voice combine to make tunes. Intonation adds the speaker’s feelings and emotions, and also

meanings in the speech. Meter is the formal rhythm of verse, but prose also has rhythm. Regular beat, accent (stress) rise

and fall etc. in poetry makes rhythm but in prose these are less regular.

Onomatopoeia

It is the use of the sound of words, imitation of the sound of animals, things or someone. The words or sound suggest the

object, the scene or the incident. Hiss, buzz, gurgle etc. are onomatopoeic words. From Alfred Lord Tennyson's The

Princess:

The moan of doves in immemorial elms,

And murmuring of innumerable bees

Euphony and Cacophony

Online Encyclopaedia Britannica mentions that Euphony and cacophony refer to the sound patterns used in verse to

achieve opposite effects. Euphony is pleasing and harmonious but cacophony is harsh and discordant. In Euphony, vowel

sounds in words for serene imagery. Vowel sounds, rather than consonant sounds, are more euphonious; the longer vowels

are the most melodious. Liquid and nasal consonants and the semivowel sounds (l, m, n, r, y, w) are also considered to be

euphonious. An example may be seen in “The Lotos-Eaters” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson: “The mild-eyed melancholy

Lotos-eaters came.” Cacophony is usually produced by combinations of words that require a staccato, explosive delivery.

Inadvertent cacophony is a mark of a defective style. Used skillfully for a specific effect, however, it vitalizes the content

of the imagery. A line in S. T. Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” illustrates cacophony:

With throats unslaked, with black lips baked,

Agape they heard me call.

CONCLUSIONS

Sounds add aesthetic meaning to words in a text. Phonetics and phonology are analytical tools of exploring phonaesthetic

aspects of language in a text. The tools and ways of analyzing phonological meanings in texts may differ in linguistic

traditions but the various approaches have largely accepted the study of phonological meanings as a fruitful enterprise and

consider them as expressions of personal and social attitudes in literary texts. People involved in literature can extend their

study to this area of linguistics for exploring stylistic means of pleasures in a text.

NAAS Rating: 3.10 – Articles can be sent to editor@impactjournals.us

Phonaestheticism 67

REFERENCES

1. Carter, R. & et al. (2002). Working with Texts. New York: Routledge.

2. Crystal, D. (1995). Phonaesthetically speaking. English Today 42, Vol. 11, No. 2 (April 1995). CUP.

3. Firth, J.R. (1951/57). "Modes of Meaning". In : J.R. Firth (ed.) 1957. Papers in Linguistics 1934–1951

London: Oxford University Press, 190–215.

4. Firth, J R. (1957/68). "A Synopsis of Linguistic Theory, 1930-1955". In : F.R. Palmer (ed.). Selected Papers

of J.R. Firth 1952-1959. London-Harlow: Longmans, Green & Co., 168–205.

5. Firth, J. R. (1968). "Linguistic Analysis as a Study of Meaning”. In: F.R. Palmer (ed.). Selected Papers of

J.R. Firth 1952-1959. London-Harlow: Longmans, Green & Co., 12–26.

6. Leech, G.N. (1969). A Linguistic Guide to English Poetry. London: Longman Group Ltd.

7. O’Connor, J. D. (1992). Better English Pronunciation. New Delhi: UBS.

Impact Factor(JCC): 4.8397 – This article can be downloaded from www.impactjournals.us

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- 09-12-2022-1670567289-6-Impact - Ijrhal-06Documento17 pagine09-12-2022-1670567289-6-Impact - Ijrhal-06Impact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- 12-11-2022-1668238142-6-Impact - Ijrbm-01.Ijrbm Smartphone Features That Affect Buying Preferences of StudentsDocumento7 pagine12-11-2022-1668238142-6-Impact - Ijrbm-01.Ijrbm Smartphone Features That Affect Buying Preferences of StudentsImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- 14-11-2022-1668421406-6-Impact - Ijrhal-01. Ijrhal. A Study On Socio-Economic Status of Paliyar Tribes of Valagiri Village AtkodaikanalDocumento13 pagine14-11-2022-1668421406-6-Impact - Ijrhal-01. Ijrhal. A Study On Socio-Economic Status of Paliyar Tribes of Valagiri Village AtkodaikanalImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- 19-11-2022-1668837986-6-Impact - Ijrhal-2. Ijrhal-Topic Vocational Interests of Secondary School StudentsDocumento4 pagine19-11-2022-1668837986-6-Impact - Ijrhal-2. Ijrhal-Topic Vocational Interests of Secondary School StudentsImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- 09-12-2022-1670567569-6-Impact - Ijrhal-05Documento16 pagine09-12-2022-1670567569-6-Impact - Ijrhal-05Impact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- 19-11-2022-1668838190-6-Impact - Ijrhal-3. Ijrhal-A Study of Emotional Maturity of Primary School StudentsDocumento6 pagine19-11-2022-1668838190-6-Impact - Ijrhal-3. Ijrhal-A Study of Emotional Maturity of Primary School StudentsImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Influence of Erotic Nollywood Films Among Undergraduates of Lead City University, Ibadan, NigeriaDocumento12 pagineInfluence of Erotic Nollywood Films Among Undergraduates of Lead City University, Ibadan, NigeriaImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- 12-10-2022-1665566934-6-IMPACT - IJRHAL-2. Ideal Building Design y Creating Micro ClimateDocumento10 pagine12-10-2022-1665566934-6-IMPACT - IJRHAL-2. Ideal Building Design y Creating Micro ClimateImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- 28-10-2022-1666956219-6-Impact - Ijrbm-3. Ijrbm - Examining Attitude ...... - 1Documento10 pagine28-10-2022-1666956219-6-Impact - Ijrbm-3. Ijrbm - Examining Attitude ...... - 1Impact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- 25-10-2022-1666681548-6-IMPACT - IJRHAL-4. IJRHAL-Challenges of Teaching Moral and Ethical Values in An Age of Instant GratificationDocumento4 pagine25-10-2022-1666681548-6-IMPACT - IJRHAL-4. IJRHAL-Challenges of Teaching Moral and Ethical Values in An Age of Instant GratificationImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Effect of Sahaja Yoga Meditation in Reducing Anxiety Level of Class Vi Students Towards English As A Second LanguageDocumento8 pagineEffect of Sahaja Yoga Meditation in Reducing Anxiety Level of Class Vi Students Towards English As A Second LanguageImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Effect of Organizational Commitment On Research and Development Performance of Academics: An Empirical Analysis in Higher Educational InstitutionsDocumento12 pagineEffect of Organizational Commitment On Research and Development Performance of Academics: An Empirical Analysis in Higher Educational InstitutionsImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- 15-10-2022-1665806338-6-IMPACT - IJRBM-1. IJRBM Theoretical and Methodological Problems of Extra-Budgetary Accounting in Educational InstitutionsDocumento10 pagine15-10-2022-1665806338-6-IMPACT - IJRBM-1. IJRBM Theoretical and Methodological Problems of Extra-Budgetary Accounting in Educational InstitutionsImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- 11-10-2022-1665489521-6-IMPACT - IJRHAL-Analysing The Matrix in Social Fiction and Its Relevance in Literature.Documento6 pagine11-10-2022-1665489521-6-IMPACT - IJRHAL-Analysing The Matrix in Social Fiction and Its Relevance in Literature.Impact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- 02-09-2022-1662112193-6-Impact - Ijrhal-1. Ijrhal - Shifting Gender Roles A Comparative Study of The Victorian Versus The Contemporary TimesDocumento12 pagine02-09-2022-1662112193-6-Impact - Ijrhal-1. Ijrhal - Shifting Gender Roles A Comparative Study of The Victorian Versus The Contemporary TimesImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- 21-09-2022-1663757720-6-Impact - Ijranss-3. Ijranss - The Role and Objectives of Criminal LawDocumento8 pagine21-09-2022-1663757720-6-Impact - Ijranss-3. Ijranss - The Role and Objectives of Criminal LawImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- 27-10-2022-1666851544-6-IMPACT - IJRANSS-2. IJRANSS - A Review On Role of Ethics in Modern-Day Research Assignment - 1Documento6 pagine27-10-2022-1666851544-6-IMPACT - IJRANSS-2. IJRANSS - A Review On Role of Ethics in Modern-Day Research Assignment - 1Impact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- 05-09-2022-1662375638-6-Impact - Ijranss-1. Ijranss - Analysis of Impact of Covid-19 On Religious Tourism Destinations of Odisha, IndiaDocumento12 pagine05-09-2022-1662375638-6-Impact - Ijranss-1. Ijranss - Analysis of Impact of Covid-19 On Religious Tourism Destinations of Odisha, IndiaImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- 07-09-2022-1662545503-6-Impact - Ijranss-2. Ijranss - Role of Bio-Fertilizers in Vegetable Crop Production A ReviewDocumento6 pagine07-09-2022-1662545503-6-Impact - Ijranss-2. Ijranss - Role of Bio-Fertilizers in Vegetable Crop Production A ReviewImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- 22-09-2022-1663824012-6-Impact - Ijranss-5. Ijranss - Periodontics Diseases Types, Symptoms, and Its CausesDocumento10 pagine22-09-2022-1663824012-6-Impact - Ijranss-5. Ijranss - Periodontics Diseases Types, Symptoms, and Its CausesImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- 19-09-2022-1663587287-6-Impact - Ijrhal-3. Ijrhal - Instability of Mother-Son Relationship in Charles Dickens' Novel David CopperfieldDocumento12 pagine19-09-2022-1663587287-6-Impact - Ijrhal-3. Ijrhal - Instability of Mother-Son Relationship in Charles Dickens' Novel David CopperfieldImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- 20-09-2022-1663649149-6-Impact - Ijrhal-2. Ijrhal - A Review of Storytelling's Role and Effect On Language Acquisition in English Language ClassroomsDocumento10 pagine20-09-2022-1663649149-6-Impact - Ijrhal-2. Ijrhal - A Review of Storytelling's Role and Effect On Language Acquisition in English Language ClassroomsImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- 28-09-2022-1664362344-6-Impact - Ijrhal-4. Ijrhal - Understanding The Concept of Smart City and Its Socio-Economic BarriersDocumento8 pagine28-09-2022-1664362344-6-Impact - Ijrhal-4. Ijrhal - Understanding The Concept of Smart City and Its Socio-Economic BarriersImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- 21-09-2022-1663757902-6-Impact - Ijranss-4. Ijranss - Surgery, Its Definition and TypesDocumento10 pagine21-09-2022-1663757902-6-Impact - Ijranss-4. Ijranss - Surgery, Its Definition and TypesImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- 24-09-2022-1664015374-6-Impact - Ijranss-6. Ijranss - Patterns of Change Among The Jatsas Gleaned From Arabic and Persian SourcesDocumento6 pagine24-09-2022-1664015374-6-Impact - Ijranss-6. Ijranss - Patterns of Change Among The Jatsas Gleaned From Arabic and Persian SourcesImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparison of Soil Properties Collected From Nalgonda, Ranga Reddy, Hyderabad and Checking Its Suitability For ConstructionDocumento8 pagineComparison of Soil Properties Collected From Nalgonda, Ranga Reddy, Hyderabad and Checking Its Suitability For ConstructionImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- 01-10-2022-1664607817-6-Impact - Ijrbm-2. Ijrbm - Innovative Technology in Indian Banking Sector-A Prospective AnalysisDocumento4 pagine01-10-2022-1664607817-6-Impact - Ijrbm-2. Ijrbm - Innovative Technology in Indian Banking Sector-A Prospective AnalysisImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- Study and Investigation On The Red and Intangible Cultural Sites in Guangdong - Chasing The Red Mark and Looking For The Intangible Cultural HeritageDocumento14 pagineStudy and Investigation On The Red and Intangible Cultural Sites in Guangdong - Chasing The Red Mark and Looking For The Intangible Cultural HeritageImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- 29-08-2022-1661768824-6-Impact - Ijrhal-9. Ijrhal - Here The Sky Is Blue Echoes of European Art Movements in Vernacular Poet Jibanananda DasDocumento8 pagine29-08-2022-1661768824-6-Impact - Ijrhal-9. Ijrhal - Here The Sky Is Blue Echoes of European Art Movements in Vernacular Poet Jibanananda DasImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- 25-08-2022-1661426015-6-Impact - Ijrhal-8. Ijrhal - Study of Physico-Chemical Properties of Terna Dam Water Reservoir Dist. Osmanabad M.S. - IndiaDocumento6 pagine25-08-2022-1661426015-6-Impact - Ijrhal-8. Ijrhal - Study of Physico-Chemical Properties of Terna Dam Water Reservoir Dist. Osmanabad M.S. - IndiaImpact JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- Cahya Indah R.Documento17 pagineCahya Indah R.Naufal SatryaNessuna valutazione finora

- Los Probes - Hunger of Memory PDFDocumento7 pagineLos Probes - Hunger of Memory PDFCharlene ChiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bor CelleDocumento11 pagineBor CelleAdi KhardeNessuna valutazione finora

- Booking A Train Ticket Activities Before Listening: H I F D A G J B C eDocumento2 pagineBooking A Train Ticket Activities Before Listening: H I F D A G J B C eMorshedHumayunNessuna valutazione finora

- PDL2 Offline Translator For SGI (Version 5.6x) : RoboticaDocumento4 paginePDL2 Offline Translator For SGI (Version 5.6x) : RoboticaRodrigo Caldeira SilvaNessuna valutazione finora

- Śivāgamādimāhātmyasa Graha of Śālivā I JñānaprakāśaDocumento111 pagineŚivāgamādimāhātmyasa Graha of Śālivā I JñānaprakāśasiddhantaNessuna valutazione finora

- PCM Lab ManualDocumento5 paginePCM Lab ManualSakshi DewadeNessuna valutazione finora

- First Periodical Exam in Mathematics 3Documento2 pagineFirst Periodical Exam in Mathematics 3kentjames corales100% (8)

- WAA01 01 Rms 20170816Documento12 pagineWAA01 01 Rms 20170816RafaNessuna valutazione finora

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocumento9 pagineDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesAmelyn Goco MañosoNessuna valutazione finora

- READMEDocumento2 pagineREADMELailaNessuna valutazione finora

- RATS 7.0 User's GuideDocumento650 pagineRATS 7.0 User's GuideAFAT92Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ball Games Writing Lesson PlanDocumento4 pagineBall Games Writing Lesson PlancarlosvazNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 2 - Basic Tools For WritingDocumento58 pagineLesson 2 - Basic Tools For WritingNorhayati Hj BasriNessuna valutazione finora

- TR 94 40.psDocumento85 pagineTR 94 40.psIshtiaqUrRehmanNessuna valutazione finora

- 7 ProverbsDocumento108 pagine7 Proverbsru4angelNessuna valutazione finora

- The Reason: HoobastankDocumento3 pagineThe Reason: HoobastankStefanie Fernandez VarasNessuna valutazione finora

- B7 - LociDocumento34 pagineB7 - Locipqpt8pqwnpNessuna valutazione finora

- Workflow Performance Configuration in 12th ReleaseDocumento67 pagineWorkflow Performance Configuration in 12th Releasesaloni panseNessuna valutazione finora

- Sem 4Documento13 pagineSem 4Neha Shrimali0% (1)

- انكليزي دور ثاني 2014Documento2 pagineانكليزي دور ثاني 2014Ploop2000Nessuna valutazione finora

- CattiDocumento75 pagineCattiClaudia ClaudiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Annotated Bibliography Grading RubricDocumento3 pagineAnnotated Bibliography Grading RubricmamcgillNessuna valutazione finora

- Agha Shahid Ali 2012 6Documento21 pagineAgha Shahid Ali 2012 6Sofija ŽivkovićNessuna valutazione finora

- The Philosophical Sense of Theaetetus' MathematicsDocumento26 pagineThe Philosophical Sense of Theaetetus' MathematicsDoccccccccccNessuna valutazione finora

- The Song of Solomon A Study of Love Sex Marriage and Romance by Tommy NelsonDocumento50 pagineThe Song of Solomon A Study of Love Sex Marriage and Romance by Tommy NelsonDeoGratius KiberuNessuna valutazione finora

- Compute Assign Increment Decrement Get Display: Count Initialval LastvalDocumento3 pagineCompute Assign Increment Decrement Get Display: Count Initialval LastvalNa O LeNessuna valutazione finora

- VHDL Cheat SheetDocumento2 pagineVHDL Cheat SheetDaniloMoceriNessuna valutazione finora

- PM 0031Documento68 paginePM 0031BOSS BOSSNessuna valutazione finora

- Tugas Week 8 Task 6 Muhammad Afuza AKbar 22323111Documento4 pagineTugas Week 8 Task 6 Muhammad Afuza AKbar 22323111Muhammad Afuza AkbarNessuna valutazione finora