Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Transcendentalism

Caricato da

choobiCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Transcendentalism

Caricato da

choobiCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Transcendentalism is based on intersubjectivity and the view that

individuals can discover their true self (the '1') by a process of transcendental reflection. When human

beings achieve this they can

then understand the other as 'another I' or an alter ego. The bestknown

proponent of this view is Husser! (1962). Other philosophers

such as Heidegger (1962) and Sartre (1958) are sometimes associated

with the views of Husser! (Theunissen, 1984), but they did

reject many of his ideas. For example, Heidegger did not believe

that individuals can use the process of totally 'bracketing' life

experiences to gain access to the intersubjective true self, as did

Husser!' The perspectives of Husser! and those of Heidegger are

basically analogous except for their differing views on bracketing.

Sartre, although influenced by Husser! and, most profoundly, by

Heidegger, was an existentialist. His existentialism is depicted in his

book Being and Nothingness (1958). The book's central theme

contests the conflict that exists between objective things and human

consciousness. Sartre's view was that humans are free in their

actions, they can determine their own destiny and that not to

acknowledge this is a dishonesty to self or, as he saw it, 'bad faith'.

Broadly speaking, transcendentalism views human beings and

identity by internal intersubjective processes. It should be pointed

out, however, that the distinction between transcendentalism and

dialogicalism is not clear-cut. For example, the views of Sartre

(1958) could be seen as spanning both perspectives. In his view,

'being' exists as an immediate presence - others help me find my

true self - but self-determination also has a place. Immediacy in

relationship interactions is also central to dialogicalism. Sartre

further asserted that we can be dehumanised or objectified through

materials. As will be explored below, this is quite similar to

dialogicalism.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- CIP Com Dev 2018Documento4 pagineCIP Com Dev 2018choobiNessuna valutazione finora

- ACCOMPLISHMENT REPORT On FAC. DEVDocumento3 pagineACCOMPLISHMENT REPORT On FAC. DEVchoobiNessuna valutazione finora

- Advanced Concepts in Critical Care NursingDocumento3 pagineAdvanced Concepts in Critical Care Nursingchoobi100% (1)

- Universal Prec QuestionsDocumento8 pagineUniversal Prec QuestionschoobiNessuna valutazione finora

- NEW BSN CURRICULUM - CMO 15 RevisedDocumento2 pagineNEW BSN CURRICULUM - CMO 15 RevisedchoobiNessuna valutazione finora

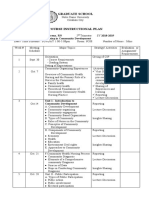

- Nres 1 Instructional PlanDocumento10 pagineNres 1 Instructional PlanchoobiNessuna valutazione finora

- level-of-disaster-preparedness-EDITED 1Documento16 paginelevel-of-disaster-preparedness-EDITED 1choobiNessuna valutazione finora

- Nurse RoleDocumento1 paginaNurse RolechoobiNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessment of Pulse SitesDocumento2 pagineAssessment of Pulse SiteschoobiNessuna valutazione finora

- Your Time Is LimitedDocumento1 paginaYour Time Is LimitedchoobiNessuna valutazione finora

- EVAL School Health NursingDocumento4 pagineEVAL School Health NursingchoobiNessuna valutazione finora

- Quiz On School Health NursingDocumento7 pagineQuiz On School Health Nursingchoobi0% (2)

- Caselet School HealthDocumento3 pagineCaselet School HealthchoobiNessuna valutazione finora

- Community Health Nursing Exam 2Documento8 pagineCommunity Health Nursing Exam 2choobi100% (9)

- Eval Exam CHNDocumento4 pagineEval Exam CHNchoobiNessuna valutazione finora