Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Nouns

Caricato da

egyptfutureDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Nouns

Caricato da

egyptfutureCopyright:

Formati disponibili

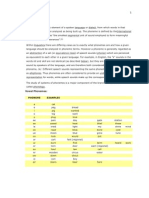

Nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs form open classes – word classes that readily

accept new members, such as the noun celebutante (a celebrity who frequents the

fashion circles), and other similar relatively new words.[2] The others are considered to

be closed classes. For example, it is rare for a new pronoun to enter the language.

Determiners, traditionally classified along with adjectives, have not always been regarded

as a separate part of speech. Interjections are another word class, but these are not

described here as they do not form part of the clause and sentence structure of the

language.[2]

Linguists generally accept nine English word classes: the noun, the verb, the adjective,

the adverb, the pronoun, the preposition, the conjunction, the determiner and the

exclamation. English words are not generally marked for word class. It is not usually

possible to tell from the form of a word which class it belongs to except, to some extent,

in the case of words with inflectional endings or derivational suffixes. On the other hand,

most words belong to more than one word class. For example, run can serve as either a

verb or a noun (these are regarded as two different lexemes).[3] Lexemes may

be inflected to express different grammatical categories. The lexeme run has the

forms runs, ran, runny, runner, and running.[3] Words in one class can sometimes

be derived from those in another. This has the potential to give rise to new words. The

noun aerobics has recently given rise to the adjective aerobicized.[3]

Words combine to form phrases. A phrase typically serves the same function as a word

from some particular word class.[3] For example, my very good friend Peter is a phrase

that can be used in a sentence as if it were a noun, and is therefore called a noun

phrase. Similarly, adjectival phrases and adverbial phrases function as if they were

adjectives or adverbs, but with other types of phrases the terminology has different

implications. For example, a verb phrase consists of a verb together with any objects and

other dependents; a prepositional phrase consists of a preposition and

its complement (and is therefore usually a type of adverbial phrase); and a determiner

phrase is a type of noun phrase containing a determiner.

Nouns[edit]

Many common suffixes form nouns from other nouns or from other types of words, such

as -age (as in shrinkage), -hood (as in sisterhood), and so on,[3] although many nouns are

base forms not containing any such suffix (such as cat, grass, France). Nouns are also

often created by conversion of verbs or adjectives, as with the words talk and reading (a

boring talk, the assigned reading).

Nouns are sometimes classified semantically (by their meanings) as proper nouns and

common nouns (Cyrus, China vs. frog, milk) or as concrete nouns and abstract

nouns (book, laptop vs. heat, prejudice).[4] A grammatical distinction is often made

between count (countable) nouns such as clock and city, and non-count (uncountable)

nouns such as milk and decor.[5] Some nouns can function both as countable and as

uncountable such as the word "wine" (This is a good wine, I prefer red wine).

Countable nouns generally have singular and plural forms.[4] In most cases the plural is

formed from the singular by adding -[e]s (as in dogs, bushes), although there are

also irregular forms (woman/women, foot/feet, etc.), including cases where the two forms

are identical (sheep, series). For more details, see English plural. Certain nouns can be

used with plural verbs even though they are singular in form, as in The government were

... (where the government is considered to refer to the people constituting the

government). This is a form of synesis; it is more common in British than American

English. See English plural § Singulars with collective meaning treated as plural.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- English GrammarDocumento18 pagineEnglish GrammarMaria AndreeaNessuna valutazione finora

- English Grammar - WikipediaDocumento33 pagineEnglish Grammar - WikipediaThulaniNessuna valutazione finora

- English Grammar - Wikipedia PDFDocumento129 pagineEnglish Grammar - Wikipedia PDFKuko sa paaNessuna valutazione finora

- English Grammar WikiDocumento224 pagineEnglish Grammar Wikicantor2000100% (1)

- NP From The NetDocumento9 pagineNP From The NetAleksandra Sasha JovicNessuna valutazione finora

- English GrammarDocumento61 pagineEnglish GrammarParas SindhiNessuna valutazione finora

- Open Class (Linguistics)Documento15 pagineOpen Class (Linguistics)Muhammad Shofyan IskandarNessuna valutazione finora

- AdverbDocumento6 pagineAdverbCheEd'zz EQi RozcHaaNessuna valutazione finora

- Eng Grammar XT 3Documento1 paginaEng Grammar XT 3fodrahostoNessuna valutazione finora

- Jump To Navigation Jump To Search: For Other Uses, SeeDocumento10 pagineJump To Navigation Jump To Search: For Other Uses, SeePhantomlayenNessuna valutazione finora

- Morphological ProcessesDocumento19 pagineMorphological ProcessesLuqman HakimNessuna valutazione finora

- Adverbs in EnglishDocumento3 pagineAdverbs in EnglishWhy Short100% (1)

- Mohammad Fadly Fathon'a - F22120076Documento3 pagineMohammad Fadly Fathon'a - F22120076MOHAMMAD FADLY FATHON'ANessuna valutazione finora

- AdverbDocumento5 pagineAdverbRavi InderNessuna valutazione finora

- Parts of SpeechDocumento11 pagineParts of Speechneeraj punjwaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Classification of NounsDocumento19 pagineClassification of NounsHadi Wardhana100% (1)

- Word ClassesDocumento6 pagineWord Classesერთად ვისწავლოთ ინგლისური ენაNessuna valutazione finora

- Assmt Grammar HBET 2103Documento16 pagineAssmt Grammar HBET 2103Wan Salmizan AzhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Vowel Phonemes: Phoneme ExamplesDocumento6 pagineVowel Phonemes: Phoneme ExamplesAnna Rhea BurerosNessuna valutazione finora

- Morphology - Study of Internal Structure of Words. It Studies The Way in Which WordsDocumento6 pagineMorphology - Study of Internal Structure of Words. It Studies The Way in Which WordsKai KokoroNessuna valutazione finora

- How Language Works - CHAPTER7 - 140110Documento33 pagineHow Language Works - CHAPTER7 - 140110minoasNessuna valutazione finora

- Dharamashastra National Law Univeristy: Legal Methods Project WorkDocumento14 pagineDharamashastra National Law Univeristy: Legal Methods Project Workarooshi SambyalNessuna valutazione finora

- Part of Speech: Noun Verb Adjective Adverb Pronoun Preposition Conjunction Interjection Numeral Article DeterminerDocumento7 paginePart of Speech: Noun Verb Adjective Adverb Pronoun Preposition Conjunction Interjection Numeral Article DeterminerbadikNessuna valutazione finora

- HTTPDocumento3 pagineHTTPAida Novi ProfilNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 3 Word ClassesDocumento93 pagineUnit 3 Word ClassesJesuv Cristian CleteNessuna valutazione finora

- FileContent 9Documento103 pagineFileContent 9Samadashvili ZukaNessuna valutazione finora

- History: o o o o o oDocumento4 pagineHistory: o o o o o oPRNessuna valutazione finora

- CSEET Business Communication May 2022 Revision NotesDocumento42 pagineCSEET Business Communication May 2022 Revision NotesSAHAJPREET BHUSARINessuna valutazione finora

- Basic Morphological Concepts: Lexemes and Word-Forms, Morphemes, Affixes...Documento11 pagineBasic Morphological Concepts: Lexemes and Word-Forms, Morphemes, Affixes...AnđaNessuna valutazione finora

- linguistics generative grammar φ person number gender case nouns pronounsDocumento7 paginelinguistics generative grammar φ person number gender case nouns pronounsPOMIAN IONUTNessuna valutazione finora

- LANE334-Chapter-2-Grammatical Categories EnglishDocumento38 pagineLANE334-Chapter-2-Grammatical Categories Englishمنى العليميNessuna valutazione finora

- Pertemuan 5 - WordsDocumento7 paginePertemuan 5 - WordsAnnisaNurulFadilahNessuna valutazione finora

- CompositionDocumento5 pagineCompositionJumberi AmaghlobeliNessuna valutazione finora

- Clauses Phrases Reviewed 2Documento6 pagineClauses Phrases Reviewed 2Marvelous AmarachiNessuna valutazione finora

- Part of Speech - WikipediaDocumento8 paginePart of Speech - WikipediaRain TolentinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Content Words and Structure WordsDocumento4 pagineContent Words and Structure WordsdeepkrishnanNessuna valutazione finora

- Adverb: Adverbs in EnglishDocumento3 pagineAdverb: Adverbs in EnglishisnaraNessuna valutazione finora

- RT of SpeechDocumento7 pagineRT of SpeechDavid Vijay ColeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Structure of English LanguageDocumento15 pagineThe Structure of English LanguageMusersame100% (1)

- Parts of Speech, Words Classified According To Their Functions in Sentences, For Purposes ofDocumento3 pagineParts of Speech, Words Classified According To Their Functions in Sentences, For Purposes ofRhitzle AnnNessuna valutazione finora

- Non Productive WaysDocumento6 pagineNon Productive WaysArailym DarkhanovnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Non Productive WaysDocumento6 pagineNon Productive WaysArailym DarkhanovnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Referat Analiza Contrastiva - The Adjective - in English and Romanian LanguageDocumento7 pagineReferat Analiza Contrastiva - The Adjective - in English and Romanian LanguagePana CostiNessuna valutazione finora

- Makalah MorphologyDocumento16 pagineMakalah MorphologyDMaliezNessuna valutazione finora

- 1.1 Background of The PaperDocumento8 pagine1.1 Background of The PaperFACHRIANI -2020-BLOK 3Nessuna valutazione finora

- Zikri's UTS MorphologyDocumento14 pagineZikri's UTS MorphologyHamka MobileNessuna valutazione finora

- Types of Use : Latin Calque Ancient Greek Inflected DeclensionDocumento3 pagineTypes of Use : Latin Calque Ancient Greek Inflected DeclensionPriya Samprith ShettyNessuna valutazione finora

- Morphology NotesDocumento19 pagineMorphology Notesmuhammad faheem100% (1)

- The Structure of English LanguageDocumento35 pagineThe Structure of English LanguageAlexandre Alieem100% (3)

- Modifiers Verbs Verb Phrases: Certainly We Need To Act (Certainly Modifies The Sentence As A Whole)Documento3 pagineModifiers Verbs Verb Phrases: Certainly We Need To Act (Certainly Modifies The Sentence As A Whole)Priya Samprith ShettyNessuna valutazione finora

- Lectures 7, 8 - Word Classes + ExercisesDocumento28 pagineLectures 7, 8 - Word Classes + ExercisestbericaNessuna valutazione finora

- Makalah-Relationship LexemesDocumento10 pagineMakalah-Relationship LexemesSoviatur rokhmaniaNessuna valutazione finora

- Makalah Morphology PDFDocumento13 pagineMakalah Morphology PDFTiara WardoyoNessuna valutazione finora

- Linguistic Signs, A Combination Between A Sound Image /buk/ or An Actual Icon of ADocumento5 pagineLinguistic Signs, A Combination Between A Sound Image /buk/ or An Actual Icon of AChiara Di nardoNessuna valutazione finora

- Presentasi AdverbDocumento13 paginePresentasi AdverbZulkifli Paldana Akbar100% (1)

- Comprehensive English Grammar Guide: From Basics to Competitive ExcellenceDa EverandComprehensive English Grammar Guide: From Basics to Competitive ExcellenceNessuna valutazione finora

- The Right Word: A Writer's Toolkit of Grammar, Vocabulary and Literary TermsDa EverandThe Right Word: A Writer's Toolkit of Grammar, Vocabulary and Literary TermsNessuna valutazione finora

- Everyday English: How to Say What You Mean and Write Everything RightDa EverandEveryday English: How to Say What You Mean and Write Everything RightNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding Grammatical Names and FunctionsDa EverandUnderstanding Grammatical Names and FunctionsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (3)

- On the Evolution of Language: First Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1879-80, Government Printing Office, Washington, 1881, pages 1-16Da EverandOn the Evolution of Language: First Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1879-80, Government Printing Office, Washington, 1881, pages 1-16Nessuna valutazione finora

- Development: Vulnhub Walkthrough: CTF Challenges May 17, 2019 Raj ChandelDocumento14 pagineDevelopment: Vulnhub Walkthrough: CTF Challenges May 17, 2019 Raj Chandeleve johnsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Step2 HackingDocumento17 pagineStep2 Hackingمولن راجفNessuna valutazione finora

- Elementary AlgorithmsDocumento618 pagineElementary AlgorithmsAditya Paliwal100% (1)

- Byzantine MarriageDocumento10 pagineByzantine MarriageHüseyin Can AKYILDIZNessuna valutazione finora

- Week 10 Business Letter WritingDocumento17 pagineWeek 10 Business Letter Writingprince12Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ancient - The Greek and Persian Wars 500-323BC - OspreyDocumento51 pagineAncient - The Greek and Persian Wars 500-323BC - Ospreyjldrag100% (15)

- PilotDocumento3 paginePilotkgaviolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Review Questionnaire in DanceDocumento3 pagineReview Questionnaire in DanceJessa MitraNessuna valutazione finora

- The Word Basics-1Documento19 pagineThe Word Basics-1Anonymous W1mhVQemNessuna valutazione finora

- Yii Framework 2.0 API DocumentationDocumento25 pagineYii Framework 2.0 API DocumentationArlin Garcia EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary of Experience: Chalakanth ReddyDocumento12 pagineSummary of Experience: Chalakanth ReddychalakanthNessuna valutazione finora

- Inama Ku Mirire Nibyo Kuryaupdated FinalDocumento444 pagineInama Ku Mirire Nibyo Kuryaupdated Finalbarutwanayo olivier100% (1)

- EAPP Quiz 1Documento36 pagineEAPP Quiz 1Raquel FiguracionNessuna valutazione finora

- Debashish Mishra: EducationDocumento2 pagineDebashish Mishra: Educationvarun sahaniNessuna valutazione finora

- New Inside Out Pre Intermediate CM PDFDocumento2 pagineNew Inside Out Pre Intermediate CM PDFAnja ChetyrkinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Profil Bahan Ajar Biologi SMA Kelas X Di Kecamatan Ilir Barat I Palembang Dari Perspektif Literasi SainsDocumento9 pagineProfil Bahan Ajar Biologi SMA Kelas X Di Kecamatan Ilir Barat I Palembang Dari Perspektif Literasi SainsIndah Karunia SariNessuna valutazione finora

- Integrated Payroll User GuideDocumento5 pagineIntegrated Payroll User GuideJill ShawNessuna valutazione finora

- En3c01b18-Evolution of Literary Movements The Shapers of DestinyDocumento1 paginaEn3c01b18-Evolution of Literary Movements The Shapers of DestinyNaijo MusicsNessuna valutazione finora

- SW7 - Themes9 - 10-Further PracticeDocumento6 pagineSW7 - Themes9 - 10-Further PracticePhuongNessuna valutazione finora

- Sentence Structure PACDocumento11 pagineSentence Structure PACMenon HariNessuna valutazione finora

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Software Expansion For STM32CubeDocumento8 pagineArtificial Intelligence (AI) Software Expansion For STM32CubeNewRiverXNessuna valutazione finora

- Digital Labour Virtual WorkDocumento342 pagineDigital Labour Virtual WorkventolinNessuna valutazione finora

- Natural Law, by José FaurDocumento30 pagineNatural Law, by José Faurdramirezg100% (2)

- Asmaa Was Sifaa - Bin BaazDocumento7 pagineAsmaa Was Sifaa - Bin BaazIbadulRahmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Railway Managment SystemDocumento11 pagineRailway Managment SystemRubab tariqNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 кл 4 четв ҚМЖDocumento17 pagine2 кл 4 четв ҚМЖNazNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapters 2 and 3 Notes: Parallel Lines and Triangles: ConstructionsDocumento3 pagineChapters 2 and 3 Notes: Parallel Lines and Triangles: ConstructionsFiffy Nadiah SyafiahNessuna valutazione finora

- Information Technology Activity Book Prokopchuk A R Gavrilova eDocumento75 pagineInformation Technology Activity Book Prokopchuk A R Gavrilova eNatalya TushakovaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lectures Hands-On HTMLDocumento66 pagineLectures Hands-On HTMLAfar SalvadoraNessuna valutazione finora

- Guru Nanak Institute of Pharmaceutical Science and TechnologyDocumento13 pagineGuru Nanak Institute of Pharmaceutical Science and TechnologySomali SenguptaNessuna valutazione finora