Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Using Health Promotion Competencies For Curriculum Development in Higher Education

Caricato da

Shenell TolsonTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Using Health Promotion Competencies For Curriculum Development in Higher Education

Caricato da

Shenell TolsonCopyright:

Formati disponibili

428818

2012

GHP19110.1177/1757975911428818W. Madsen and T. BellGlobal Health Promotion

Original Article

Using health promotion competencies

for curriculum development in higher education

Wendy Madsen1 and Tanya Bell1

Abstract: Health promotion core competencies are used for a variety of reasons. Recently there have

been moves to gain international consensus regarding core competencies within health promotion.

One of the main reasons put forward for having core competencies is to guide curriculum development

within higher education institutions. This article outlines the endeavours of one institution to develop

undergraduate and postgraduate curricula around the Australian core competencies for health

promotion practitioners. It argues that until core competencies have been agreed upon internationally,

basing curricula on these carries a risk associated with change. However, delaying curricula until such

risks are ameliorated decreases opportunities to deliver dynamic and current health promotion education

within higher institutions. (Global Health Promotion, 2012; 19(1): 43–49)

Keywords: education, health promotion

Introduction as the discipline grows and matures within a praxis

context rather than one that is strictly theoretical

Although various aspects of what we now or academic. This raises questions for those teaching

understand as health promotion have been evident into health promotion programs at undergraduate

in different guises for a number of centuries, health or postgraduate levels regarding how to prepare

promotion has been emerging as a distinct discipline the curricula for these programs: what is to be

since 1986 as heralded by the Ottawa Charter. As included? How is it to be taught? How can theory

such, there is still debate as to what constitutes inform practice? How is practice driving theoretical

health promotion in a way that is not seen in older, developments? This article explores how one higher

more established discipline areas such as medicine educational institution has approached these

or law. One of the consequences of this ongoing challenges using national core competencies for

debate is a lack of certainty for those teaching the health promotion practitioners as the basis of

new generation of health promotion practitioners. curricula. A brief outline of the development of core

Traditionally, academia has provided the nurturing competencies will be offered as the context within

grounds for new professionals, steeping novices in which the curricula were constructed, followed by

the culture of the professional discipline area, a presentation of the curricula models and a

feeding their minds with the concepts and knowledge discussion of the limitations of taking this approach.

needed to emerge as graduates and take up their Throughout this article, it will be argued that while

positions in society and the profession. Tradition there are risks associated with using core

and research formed the basis of such nurturing competencies as the foundation of curricula in a

grounds. However, for emerging fields of study and climate of ongoing change, the benefits of keeping

disciplines such as health promotion, there is more the curricula dynamic and relevant to health

of a ‘chicken-and-egg’ situation within academia promotion outweigh the concerns.

1. CQ University, Bundaberg, Australia. Correspondence to: Wendy Madsen, CQ University, Locked Bag 3333, Bundaberg,

Qld. 4670, Australia. Email: w.madsen@cqu.edu.au

(This manuscript was submitted on September 5, 2010. Following blind peer review, it was accepted for publication

on May 26, 2011)

Global Health Promotion 1757-9759; Vol 19(1): 43 –49; 428818 Copyright © The Author(s) 2012, Reprints and permissions:

http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1757975911428818 http://ghp.sagepub.com

Downloaded from ped.sagepub.com by Pro Quest on April 11, 2012

44 W. Madsen and T. Bell

Background initially devised with course development in mind

across a range of academic levels, from undergraduate

The concept of constructing core competencies for to postgraduate degree programs (13) and have

health promotion professionals has been around some recently been updated (14). Like others, these core

time (1,2), but has gained ascendancy since the competencies outline entry level criteria for beginning

Galway Consensus Conference in 2008 that instigated health promotion practitioners. As such, one of their

the process of compiling a set of internationally primary purposes is to provide a framework for

agreed upon competencies. This conference needs to health promotion curricula.

be seen in the context of health promotion as an A number of the reasons put forward at the Galway

emerging discipline. Indeed, in their outline of the Consensus Conference for developing competencies

conference outcomes, Barry et al. (3) highlight the relate to curricula development and building the

various meanings associated with terminology used capacity of the health promotion workforce (3–5,11).

to depict health promotion and health education. The International Union for Health Promotion and

Other papers published from this conference provide Education (IUHPE) in its 2007 Shaping the future of

a clear picture of how health promotion has evolved; health promotion statement considers that core

the cultural variations within health promotion’s competencies ‘define the field and provide common

history; and the diverse workforce within health direction for curriculum development’ (15). Indeed,

promotion (4,5). Bennett et al.’s (6) analysis of public Barry’s commentary (16) regarding the work of the

health education in Australia also illustrates health IUHPE Global Vice-President for Capacity Building,

promotion has emerged from the broader discipline Education and Training highlights the challenges for

area of public health with a Masters of Public Health curricula development including: multiple levels of

being taken by disparate professionals as the qualifications to suit at least two levels of practitioners;

traditional pathway into this field. Thus, the health and the responsiveness of curricula to the needs of

promotion workforce is perceived as ‘ill-defined’, practitioners working in diverse social and political

with professional development often ‘ad hoc’ (7). contexts. However, there is an emerging consensus

The collection of papers that came out of the within the literature that, despite such challenges, the

Galway Consensus Conference offers a useful history development of core competencies for health promotion

of the development of core competencies within practitioners is useful for curriculum developers and

health promotion. A number of authors outline the provides frameworks and direction that has been

credentialing moves within the USA and the UK over previously missing. Where programs may have once

the past three decades (8–10) and the status quo been based on a compilation of multidisciplinary

within Europe (5). Battel-Kirk et al. (11) provide a courses, particularly those relevant to public health,

literature review of competencies, including the with the occasional health promotion specific course

arguments for and against going down this path, (6), programs are now becoming more prevalent that

suggesting that one of the main problems with core have been intentionally constructed for the specific

competencies is that they are often backward looking needs of health promotion practitioners. Core

rather than forward looking. Amidst this literature competencies help provide coherence to such curricula.

and that offered by others, such as Wright (12), issues Alongside discussion of competencies within

related to core competencies as setting the entry level curricula, and not just those related to health promotion,

into health promotion as a discipline are raised. In is the question of how to show a curriculum is addressing

particular, as Bennett et al. (6) indicate, there are a the competencies. This is often done by ‘mapping’ across

number of entry points into health promotion now: the curriculum. This has become increasingly popular

via undergraduate programs; specific health as generic skills have been introduced into higher

promotion postgraduate programs; as well as the education institutions and there are now a number of

more traditional Masters in Public Health. Is it computer programs that allow mapping of various

appropriate, therefore, for all of these entry points competencies (17,18). However, such mapping is often

into the practice of health promotion to have the retrospective in that its aim is to identify components

same entry level expectations? In Australia, core within an established curriculum. Howat et al. (19)

competencies for health promotion practitioners have outline a much more prospective process whereby

been available for a number of years. These were identified health promotion competencies were used to

IUHPE – Global Health Promotion Vol. 19, No. 1 2012

Downloaded from ped.sagepub.com by Pro Quest on April 11, 2012

Original Article 45

construct the curricula at undergraduate and the University of Tasmania includes global perspective

postgraduate levels. It is this latter approach that has and social responsibility among the more common

been used to construct the curricula models outlined in attributes of ‘knowledge’, ‘communication skills’ and

this article. ‘problem-solving skills’ (21). The graduate attributes

needed to be considered within the curricula outlined

Using core competencies as the basis in this article include: communication, problem solving,

critical thinking, information literacy, team work,

of curricula

information technology competence, cross cultural

In their argument about the need to bring curricula competence, and ethical practice. The inclusion of so

into higher education debates on teaching and learning, many ‘personal’ attributes confirms the three domains

Barnett and Coate (20) suggest the silence surrounding of curricula put forward by Barnett and Coate (20) of:

curriculum issues has resulted in a stealthy sliding of knowing, acting, and being. That is, any curriculum

curriculum towards a ‘skills, standards and outcomes can be considered as containing elements that relate to

model’ rather than a ‘reflexive, collective, developmental the knowledge and the manipulation of knowledge; to

and process-oriented model’. That is, that attention acting out and conducting certain skills; and to personal

has drifted towards skills rather than knowledge and development of learning to engage with knowledge

understanding. Such concerns need to be considered and practice in an authentic and meaningful way and

carefully when using core competencies as the developing an open mind towards other viewpoints.

foundation of health promotion curricula as there is The AHPA core competencies for health promotion

a danger that these will be viewed as a set of ‘skills’ practitioners relate very well to the knowing and

rather than broader competencies based on knowledge acting domains as outlined by Barnett and Coate (20).

and understanding. The Australian Health Promotion However, there is little in the way of being. Indeed, a

Association’s (AHPA) core competencies for health criticism of these core competencies would be the lack

promotion practitioners (14) indicate the competencies of attention paid to articulating the need to be a

relate to knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that reflective practitioner as the basis of professional (and

‘constitute a common baseline for all health promotion personal) development. While this attribute is often

roles’. Thus, while skills certainly feature within these implied within the core competencies and in the spirit

competencies, they are placed within a broader context in which they were developed whereby they do attach

based on health promotion program planning, importance to attitudes and values, including cultural

implementation and evaluation; partnership building; competencies, there is no explicit competency related

communication and report writing; technology; and to reflective practice. Yet, it could be argued that

knowledge competencies. It is these core competencies reflective practice is fundamental to many of the

that have been used in the curricula outlined here, with AHPA competencies and of the domains outlined by

the understanding that these competencies need to be Barry et al. (3) that are being considered as the basis

considered within their broader contexts. of international competencies for health promotion

In addition to the core competencies for health practitioners. This can be seen in earlier attempts to

promotion practitioners, many universities across the develop a European core curriculum for health

globe also want to see evidence of ‘generic’ attributes promotion (22) and in the application of competencies

embedded into curricula. This is in response to a to the development of a portfolio within the Masters

shifting role of universities within society and a need of health promotion program at the National

to better prepare graduates for the workplace (20,21). University of Galway, in Ireland, both of which place

Interestingly, many of these graduate attributes a great deal of emphasis on developing reflective

correspond with the core competencies for health practice (23). Indeed, Chiu (24) argues that critical

promotion practitioners as outlined by the AHPA and reflection and conscientization processes are very

others internationally. However, there is some useful in health promotion practice that is focused on

divergence around the areas of developing the student social transformation. It is acknowledged that the

(and graduate) as a ‘person’. While graduate attributes concept of reflective practice within health promotion

across institutions vary, some do articulate a number is contested as outlined by Issitt (25) and Cronin and

of personal qualities as being a valued part of completing Connolly (26) whereas there seems to be a greater

a degree from that particular institution. For example, acceptance of critical reflection and reflective practice

IUHPE – Global Health Promotion Vol. 19, No. 1 2012

Downloaded from ped.sagepub.com by Pro Quest on April 11, 2012

46 W. Madsen and T. Bell

was in the minds of those designing the curriculum of

the program as a whole. The models were used as the

basis for their decision making of how to piece together

various courses and what may be contained within

these courses. Thus the core competencies were woven

into the curriculum from the beginning and while these

competencies are mapped across the curriculum — that

is, constructed in a matrix that identifies which

competencies are introduced and developed in which

courses — the process was prospective.

The Masters program in health promotion will be

offered for the first time in 2011. The process of

designing the curriculum for this program followed a

similar pathway to that outlined above and the model

produced had similar purposes. The difficulty presented

here was that the AHPA core competencies are written

for entry level practitioners. In a traditional discipline,

these would be conceptualized as appropriate for

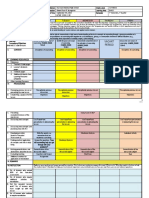

Figure 1. Curriculum model for Bachelor of Health graduates of an undergraduate program. However,

Promotion because of the multiple entry levels within the health

promotion workforce, this creates some difficulty for

developing curriculum at a postgraduate level. To

in other health disciplines such as nursing and social overcome this difficulty, the core competencies were

work. Despite this, from the basis of incorporating integrated into a curriculum model that was also based

being elements into the health promotion curricula on Transformative Learning principles. In particular,

outlined here, the curriculum design team included elements of alternative perspectives, centrality of

reflective practice strategies in both the undergraduate experience, critical reflection, collaboration, learner-

and postgraduate programs. centred approach, peer review, reflective dialogue and

The previous undergraduate curriculum was loosely self-assessment (27) were incorporated. As students

based on the AHPA 2005 core competencies as of this program need to be working in the field of

outlined by Shilton et al. (13). It was certainly possible health promotion as a prerequisite (but do not have

to map most of these competencies across the program. to have any extensive health promotion experience),

However, in 2009 as part of a major program review, taking this approach to the curriculum allows core

it was decided there needed to be a greater level of competencies to be extended beyond the entry level

focus on the Ottawa Charter and the core competencies to better meet the learning needs of these students.

within the program, and rather than fit these concepts Evidently, this approach relies heavily on self-reflective

into certain courses, it was necessary to allow these strategies as the basis of extending the core competencies

fundamental concepts to ‘drive’ the curriculum. A as students need to critique their own practices,

curriculum model was created based on these uncovering unquestioned assumptions and using each

fundamental concepts to provide a visual representation others’ experiences to construct a new collective

of the importance they played in dictating what was understanding. However, the extensive literature

included in the intended and taught curriculum. This surrounding transformative learning principles

curriculum model is illustrated in Figure 1. Barnett provides a reasonable level of confidence in this

and Coate (20) warn that such diagrammatic approach (28,29). Such an approach may not solve

representations of curricula need to be understood all problems of using entry level competencies for

from a teacher’s perspective (what is intended and postgraduate studies as outlined in the literature (6,16),

actually taught) rather than a representation of the but in the absence of any alternatives, this may provide

student’s experience of the curriculum (often termed one approach to address the dilemma. The curriculum

‘received’ curriculum). Thus, the curriculum models model for the Masters program is illustrated in

presented in this article are intended to outline what Figure 2.

IUHPE – Global Health Promotion Vol. 19, No. 1 2012

Downloaded from ped.sagepub.com by Pro Quest on April 11, 2012

Original Article 47

cultural background to health, before moving to more

knowledge based courses that picked up specific health

promotion theories and procedural competencies. This

means competencies are developed across a number

of courses, from a fundamental level in first year

courses, to a more complex understanding and

application in higher level courses. For instance, first

year students are introduced to working in teams as

part of the learning activities and assessment for

health promotion concepts, but are required to work

Figure 2. Curriculum model for Masters of Health in partnership with someone from industry in third

Promotion year as part of health promotion in practice A & B

assessment. Some aspects of the AHPA core

Integrating core competencies into a curriculum competencies are more readily divided across various

model is probably the easy part of curriculum design. courses. For example, the competency related to

The visual representations can be seen as pretty communication outlines a number of genres of

pictures, but unless the ideas contained in these writing and these were simply allocated a particular

models are distilled down to course structure, content, assessment item or activity within a particular course.

delivery and assessment levels, they remain simply as There was no precise science involved in this, but

ideas. Furthermore, competencies need to be rather a movement around of the various components

developed and woven across the entire program, to come up with a course-of-best-fit that stayed true

although some courses are likely to have a stronger to the overall curriculum model and that collectively

focus on one or two competencies. For example, the accounted for all the components. A broad outline

undergraduate course community needs assessment of how the core competencies have been mapped

relates quite specifically to the AHPA Core across a number of central courses within the Bachelor

Competency 1.1 needs (or situational) assessment of health promotion is contained in Table 1.

competencies. The process used by the teaching team Health promotion is not an accredited program in

for the programs outlined here starts by providing Australia, nor is there any regulation of programs by

students with the historical, political, social and a regulatory or credentialing body. There are no checks

Table 1. Map of Australian core competencies across Bachelor of Health Promotion central courses

Program planning, Partnership Communication Technology Knowledge

implementation and building and report writing competencies competencies

evaluation competencies competencies competencies

Foundations of √ √ √

health promotion

Health promotion √ √ √ √

concepts

Health √ √ √ √

communications

Community needs √ √ √ √ √

assessment

Health promotion √ √ √ √ √

strategies

Health promotion √ √ √ √ √

in practice A & B

Population health √ √ √

epidemiology

IUHPE – Global Health Promotion Vol. 19, No. 1 2012

Downloaded from ped.sagepub.com by Pro Quest on April 11, 2012

48 W. Madsen and T. Bell

and balances in place to ensure prospective students simply mapping competencies in retrospect. However,

or the public at large that programs being offered as indicated by Allegrante et al. (8), there do seem to

through higher education institutions are appropriate be sufficient commonalities regarding what health

for the health promotion workforce. Many universities promotion is to take the risk of basing curricula on

have industry advisory committees to help guide their these ideas. Furthermore, constructing a curriculum

decision making in regards to curricula matters, and that is based on the current and prospective competencies

this was the process used to guide the curriculum breathes life into the teaching and learning plans for

development for the programs outlined in this article. delivering health promotion programs, knowing the

However, much is expected from these industry content and strategies are up to date and relevant to

representatives, including having an understanding health promotion practitioners now and when students

of curriculum issues as well as being cognisant of graduate. Yes, changes that occur at national and

the broader industry. Integrating the AHPA core international levels may mean significant changes also

competencies into the curriculum models for the need to happen in the curriculum but rather than seeing

undergraduate and Masters level programs has kept this as a problem, such changes can be welcomed as

the knowledge, skills, attitudes and values of health opportunities to keep the curriculum dynamic and

promotion practitioners in the foreground throughout fresh. Indeed, Barnett and Coate (20) argue a

the decision making process of constructing program curriculum should be dynamic as it responds to

outcomes and subsequent course outcomes, teaching consistent internal and external influences.

strategies and assessments. Models have not replaced

the need for industry consultation, but have perhaps

eased the pressure on these representatives to be all- Conclusion

knowing, and reduced the ‘guess work’ involved. The Constructing curricula within the higher education

models also assisted in constructing more coherent sector is fraught with challenges and competing

curricula, although it is not until the programs have tensions. There are internal and external factors that

actually been taught in their entirety and evaluated need to be taken into consideration: industry concerns;

through the university systems that these impressions national and international expectations; graduate

will be confirmed or challenged. attributes; student cohort characteristics; delivery

opportunities and constraints; staffing profiles

Limitations of using core competencies and workload issues. In the absence of an external

accrediting body to oversee curricula and determine

in curricula

content and processes, as with health promotion, using

At this point in time there are no internationally core competencies for health promotion practitioners

agreed upon core competencies for health promotion as the fundamental basis of curriculum models is one

practitioners. The literature outlines moves towards way of trying to keep curricula coherent and relevant

this goal and the experiences of a handful of countries while juggling these internal and external factors. This

that have competencies that have been formally article has outlined how the AHPA core competencies

adopted as part of accreditation processes. Placing have been used to guide curriculum development in

core competencies at the very foundation of curricula one institution. Taking this approach is not without

when these have not been confirmed at an international risks as the international health promotion community

level can be seen as somewhat risky. Even the AHPA progress towards developing agreed upon core

core competencies changed quite dramatically between competencies that may not be the same as those

2005 and 2009 raising questions of whether further used to build the curriculum models outlined here,

changes would undermine curricula that have been necessitating significant revision. However, rather

based on these competencies; and given the glacial than seeing this as a threat to the curricula, curriculum

speed most university processes operate, would faculty developers should be prepared to view all changes as

be able to move quickly enough to adapt to changes opportunities to keep the teaching and learning within

that do occur to ensure the curricula remains programs dynamic and responsive to the ‘real world’

appropriate to the needs of students? Placing the of health promotion. Core competencies are not a

competencies at the core of the curriculum does mean panacea, but they do provide a framework, along with

that changes do have a potentially greater effect than research, of further engaging the tertiary sector with

IUHPE – Global Health Promotion Vol. 19, No. 1 2012

Downloaded from ped.sagepub.com by Pro Quest on April 11, 2012

Original Article 49

the health promotion industry to help ensure higher model and competency framework. Health Promot

education institutions provide an appropriate nurturing Pract. 2003; 4 (3): 293–302.

13. Shilton T, Howat P, James R, Burke,L, Hutchins C,

ground for health promotion graduates. Woodman R. Health promotion competencies for

Australia 2001-5: trends and their implications. Promot

Educ. 2008; 15 (2): 21–25.

References 14. Australian Health Promotion Association. Core

1. O’Neill M, Hills M. Education and training in health competencies for health promotion practitioners.

promotion and health education: trends, challenges and Maroochydoore; 2009.

critical issues. Promot Educ. 2000; 7 (1): 7–9. 15. International Union for Health Promotion and Education

2. McCracken H, Rance H. Developing competencies for (IUHPE). Shaping the future for health promotion:

health promotion training in Aotearoa-New Zealand. priorities for action. Promot Educ. 2007; 14 (4): 199–202.

Promot Educ. 2000; 7 (1): 40–43. 16. Barry MM. Capacity building for the future of health

3. Barry MM, Allegrante JP, Lamarre M-C, Auld ME, promotion. Promot Educ. 2008; 15 (4): 56–58.

Taub A. The Galway Consensus Conference: 17. Willett TG. Current status of curriculum mapping in

international collaboration on the development of core Canada and the UK. Med Educ. 2008; 42: 786–793.

competencies for health promotion and health 18. Cuevas NM, Matveev AG, Miller KO. Mapping general

education. Glob Health Promot. 2009; 16 (2): 5–11. education outcomes in the major: intentionality and

4. Taub A, Allegrante JP, Barry MM, Sakagami K. transparency. Peer Review. 2010; Winter: 10–15.

Perspectives on terminology and conceptual and 19. Howat P, Maycock B, Jackson L et al. Development of

professional issues in health education and health competency-based university health promotion courses.

promotion credentialing. Health Educ Behav. 2009; 36 Promot Educ. 2000; 7 (1): 33–38.

(3): 439–450. 20. Barnett R, Coate K. Engaging the curriculum in higher

5. Santa-Maria Morales ASM, Battel-Kirk B, Barry MM, education. Berkshire: Society for Research into Higher

Bosker L, Kasmel A, Griffiths J. Perspectives on health Education and Open University Press; 2005.

promotion competencies and accreditation in Europe. 21. Jones SM, Dermoundy J, Hannan G, James S, Osborn,J,

Glob Health Promot. 2009; 16 (2): 21–31. Yates B. Designing and mapping generic attributes

6. Bennett CM, Lilley K, Yeatman H, Parker E, Geelhoed E, curriculum for science undergraduate students: a faculty-

Hanna EG, Robinson P. Paving pathways: shaping the wide collaborative project. Sydney: UniServe Science

public health workforce through tertiary education. Teaching and Learning Research Conference; 2007.

Aust New Zealand Health Policy. January 2010; 7 (2). 22. Davies JK, Colomer C, Lindstrom B et al. The EUMAHP

http://www.anzhealthpolicy.com/content/7/1/2 project – the development of a European Masters program

7. O’Connor-Fleming ML, Parker E, Oldenberg B. Health in health promotion. Promot Educat. 2000; 7 (1): 15–18.

promotion workforce development in Australia. Health 23. McKenna V, Connolly C, Hodgins M. Usefulness of a

Promot J of Austral. 2000; 10 (2): 140–147. competency-based reflective portfolio for student

8. Allegrante JP, Barry MM, Auld ME, Lamarre M-C, learning on a Masters Health Promotion programme.

Taub A. Toward international collaboration on Health Educ J. 2010; 20 (10): 1–6.

credentialing in health promotion and health education: 24. Chiu LF. Critical reflection: more than nuts and bolts.

the Galway Consensus Conference. Health Educ Behav. Action Research. 2006; 4 (2): 183–203.

2009; 36 (3): 427–438. 25. Issitt M. Reflecting on reflective practice for professional

9. Cottrell RR, Lysoby L, Rasar King L, Airhihenbuwa CO, education and development in health promotion.

Roe KM, Allegrante JP. Current developments in Health Educ J. 2003; 62 (2): 173–188.

accreditation and certification for health promotion 26. Cronin M, Connolly C. Exploring the use of experiential

and health education: a perspective on systems of learning workshops and reflective practice within

quality assurance in the United States. Health Educ professional practice development for postgraduate

Behav. 2009; 36 (6): 451–463. health promotion students. Health Educ J. 2007; 66 (3):

10. Speller V, Smith BJ, Lysoby L. Development and 286–303.

utilization of professional standards in health education 27. Taylor D. Fostering Mezirow’s transformative learning

and promotion: US and UK experiences. Glob Health theory in the adult education classroom: a critical review.

Promot. 2009; 16 (2): 32–41. Can J for the Study of Adult Educ. 2000; 14 (2): 1–28.

11. Battel-Kirk B, Barry MM, Taub A, Lysoby L. A review 28. Mezirow J, Taylor EW (eds). Transformative learning in

of the international literature on health promotion practice: insights from community, workplace and higher

competencies: identifying frameworks and core education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2009.

competencies. Glob Health Promot. 2009; 16 (2): 12–20. 29. Cranton P (ed). Transformative learning in action:

12. Wright K, Hann N, McLeroy KR et al. Health insights from practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

education leadership development: a conceptual Publishers; 2007.

IUHPE – Global Health Promotion Vol. 19, No. 1 2012

Downloaded from ped.sagepub.com by Pro Quest on April 11, 2012

78 Résumés

Utiliser les compétences essentielles de la promotion de la santé pour développer

les cursus de l’enseignement supérieur

W. Madsen et T. Bell

Les compétences essentielles de la promotion de la santé sont utilisées pour diverses raisons. On a assisté

récemment à des mouvements pour parvenir à un consensus international sur les compétences essentielles

dans le domaine de la promotion de la santé. L’une des principales raisons avancées pour avoir des compétences

essentielles est de pouvoir orienter l’élaboration des cursus de l’enseignement supérieur. Cet article décrit les

efforts déployés par une institution pour développer un programme d’études autour des compétences

essentielles en Australie pour des praticiens de la promotion de la santé. Il soutient que tant qu’il n’y aura pas

eu un accord international sur les compétences essentielles en fondant les cursus sur ces compétences on

prend un risque associé à des changements potentiels. Cependant, en reportant le développement des cursus

jusqu’à ce que de tels risques aient été réduits, on diminue les opportunités de délivrer un enseignement

dynamique et actuel en matière de promotion de la santé dans les institutions d’enseignement supérieur.

(Global Health Promotion, 2012; 19(1): 43-49)

Les comportements liés à la consommation associée de substances psychoactives

chez les jeunes : l’environnement scolaire a-t-il un impact ?

M. J. E. Costello, S. T. Leatherdale, R. Ahmed, D. L. Church et J. A. Cunningham

Contexte. La consommation de substances psychoactives est courante chez les jeunes ; cependant, on a une

connaissance limité de la consommation associée de tabac, d’alcool et de marijuana. L’environnement scolaire

peut jouer un rôle important dans la probabilité pour un jeune de se livrer à des comportements à risque en

matière de consommation de substances psychoactives, et notamment de consommation associée. Objectif.

Cette étude vise à : (i) décrire la prévalence de la consommation associée de substances psychoactives chez les

jeunes ; (ii) identifier et comparer les caractéristiques des jeunes qui consomment régulièrement l’une de ces

substances, deux d’entre elles ou les trois ; (iii) examiner si la probabilité de consommation associée varie en

fonction de l’établissement scolaire ; et (iv) examiner quels facteurs sont liés à une consommation associée.

Méthodes. Cette étude a utilisé des données représentatives recueillies à l’échelle nationale auprès de lycéens,

agés de 14 à 18 ans approximativement, (n = 41886) dans le cadre de l’Enquête canadienne 2006-2007 sur

le Tabagisme chez les Jeunes. Des données démographiques et comportementales ont été recueillies parmi

lesquelles la consommation actuelle de cigarettes, d’alcool et de marijuana. Résultats. 6,5% (n = 107000) ont

rapporté une consommation courante des trois substances et 20,3% (n = 333000) de deux d’entre elles. Une

analyse multi-niveaux a révélé des variations significatives entre les écoles en ce qui concerne les probabilités

pour un lycéen de consommer l’ensemble des trois substances et deux des trois ; ce qui représente respectivement

16,9% et 13,5% de la variabilité. La consommation associée variait en fonction du sexe, de la classe, du

montant d’argent de poche disponible et de la performance scolaire perçue. Conclusions. La consommation

associée de substances psychoactives est élevée chez les jeunes. Cependant, toutes les écoles ne connaissent

pas la même prévalence. Il est important de connaître les caractéristiques du milieu scolaire qui font que

certains établissements sont plus à risques que d’autres en ce qui concerne la consommation de substances

nocives par les jeunes. Cela devrait permettre d’adapter les programmes d’éducation sur la consommation de

drogue et d’alcool. Des interventions ciblant la prévention de la consommation associée de substances

psychoactives sont nécessaires. (Global Health Promotion, 2012; 19(1): 50-59)

IUHPE – Global Health Promotion Vol. 19, No. 1 2012

Downloaded from ped.sagepub.com by Pro Quest on April 11, 2012

Resúmenes 91

Para llegar a ser una Escuela Promotora de Salud: elementos clave de la planificación

E. Senior

Este trabajo contempla los aspectos prácticos de la ejecución del marco de la Escuela Promotora de Salud (EPS),

entre ellos, la realización de una auditoria en toda la institución a fin de lograr que una escuela primaria adopte

con éxito los principios de las EPS. Se firmó un acuerdo de colaboración entre EACH Social and Community

Health, que es un Centro de Salud Comunitaria local, y una escuela primaria de las afueras de la zona este de

Melbourne (Australia). Se llevó a cabo una auditoria de la comunidad escolar para la cual se hizo el seguimiento

de 4 grupos foco de alumnos entre 8 y 11 años de edad, del 3º al 6º año. Los datos cuantitativos fueron facilitados

por veinte profesores de la escuela a lo largo de una jornada de desarrollo profesional organizada por el personal

de promoción de la salud del Centro de Salud Comunitaria. Los resultados de la auditoria escolar reflejan que

tanto los estudiantes de los cursos 3º a 6º como los padres valoraban por encima de todo el entorno exterior de

la escuela. El personal de la escuela valoraba por encima de todo los atributos del personal. Entre las sugerencias

de los alumnos figuraba la de mejorar el comedor y el entorno exterior. El personal de la escuela estaba más

preocupado por la forma física tanto propia como de los alumnos. Una de las preocupaciones de los padres era

la ausencia de una dieta sana. La comunidad escolar reconoce el valor de adoptar el marco de la EPS, pero se

constata la necesidad de prestarle un apoyo estructurado y continuado para que pueda aplicar con éxito el

enfoque de la EPS. Es necesario que la comunidad escolar entienda que la transición hacia un cambio cultural y

medioambiental es lenta. Para que el modelo de EPS se aplique con éxito se necesita tiempo y colaboración.

Habría que hacer hincapié en prestar apoyo a los profesores para que cambien la escuela desde dentro. Las

relaciones son importantes. (Global Health Promotion, 2012; 19(1): 23-31)

Relación causal entre el sentido de la coherencia y el entorno laboral psicosocial

a partir de datos de seguimiento de trabajadores japoneses adultos durante un año

T.Togari y Y.Yamakazi

El objetivo de este estudio era utilizar datos longitudinales e investigar las siguientes cuatro hipótesis en torno

a la relación entre el sentido de la coherencia (SC) y el entorno laboral (EL) en razón de los sexos: (1) Existe

una relación causa efecto bidireccional entre SC y EL; 2) el EL es la causa y el SC es el efecto; 3) el SC es la

causa y el EL es el efecto; y 4) no existe relación causa efecto entre SC y EL. Se realizó un muestreo aleatorio

estratificado en dos fases con sujetos masculinos y femeninos de edades comprendidas entre los 20 y los

40 años, residentes en Japón, y se les envió por correo unos cuestionarios autoadministrados entre enero y

marzo 2007 (Etapa 1). Se llevó a cabo un seguimiento del mismo modo de enero a marzo de 2008 (Etapa 2).

Se recibieron respuestas de 3.965 personas (ratio de seguimiento: 82,6%). Este estudio analizó las respuestas

de 1.291 varones y 933 mujeres con una edad mínima de 25 años en la Etapa 1 y que permanecieron en el

mismo trabajo en los dos periodos de tiempo. El análisis se realizó empleando un modelo de correlación de

retardos cruzado bajo modelización de ecuaciones estructurales. Se eligió la segunda hipótesis tanto para

varones como para mujeres en base al resultado de las comparaciones anidadas. Es decir, se constató una

relación temporal causa-efecto entre SC y EL tanto en los varones como en las mujeres, en el que el EL era la

causa y el SC era el efecto. (Global Health Promotion, 2012; 19(1): 32-42)

Utilizar las competencias de promoción de la salud para el desarrollo curricular

de la enseñanza superior

W. Madsen y T. Bell

Las competencias básicas de la promoción de la salud se utilizan para diversos fines. Recientemente, se han

dado pasos para lograr un consenso internacional respecto de las competencias que se consideran esenciales

IUHPE – Global Health Promotion Vol. 19 No. 1 2012

Downloaded from ped.sagepub.com by Pro Quest on April 11, 2012

92 Resúmenes

para el ejercicio de la promoción de la salud. Una de las principales razones que se argumenta para formular

competencias básicas es que sirvan de orientación para el desarrollo curricular en las instituciones de

enseñanza superior. Este artículo describe un intento institucional de desarrollar un programa de estudios

para estudiantes universitarios y de posgrado en base a las competencias básicas definidas en Australia para

los profesionales de promoción de la salud. Explica que si se incorporan las competencias básicas a los

programas de estudios antes de lograr un consenso internacional al respecto, se corre el riesgo de que luego

cambien. No obstante, aplazar la elaboración de los programas de estudios hasta que desaparezca este riesgo

reduce las oportunidades de impartir la enseñanza de promoción de la salud de manera dinámica y actualizada

en las instituciones universitarias. (Global Health Promotion, 2012; 19(1): 43-49)

Consumo comórbido de sustancias entre los jóvenes: ¿Influye el entorno escolar?

M. J. E. Costello, S. T. Leatherdale, R. Ahmed, D. L. Church y J. A. Cunningham

Antecedentes. El consumo de sustancias es corriente entre los jóvenes; no obstante, seguimos teniendo un

conocimiento limitado del consumo comórbido de tabaco, alcohol y marihuana. El entorno escolar puede

desempeñar un importante papel en la probabilidad de que un alumno se inicie en el consumo de sustancias

de alto riesgo, incluido el consumo comórbido. Objetivo. Este estudio pretende: (1) describir la prevalencia

de las conductas de consumo comórbido de sustancias en los jóvenes; (2 ) identificar y comparar las

características de los jóvenes que actualmente consumen una sola sustancia, dos o las tres; (3) investigar si la

probabilidad del consumo comórbido varia de una escuela a otra; y (4) examinar qué factores se asocian al

consumo comórbido. Métodos. Este estudio utilizó datos representativos a escala nacional de alumnos en los

cursos 9º a 12º, entre 14 y 18 años de edad aproximadamente, (n=41.886) recogidos en el Canadian Youth

Smoking Survey (YSS) (Estudio sobre el tabaco en los jóvenes canadienses) realizado en 2006-2007. Se

recogieron datos demográficos y conductuales, entre ellos, el consumo de cigarrillos, alcohol y marihuana en

aquel momento. Resultados. 6,5% (n=107.000) de los encuestados admitían consumir las tres sustancias y

20,3% (n=333.000) dos de ellas. El análisis de los diferentes niveles reveló la importancia de la escuela en las

probabilidades de que el alumno consumiera las tres sustancias o dos de ellas, lo que representó el 6,9% y

13,5% de la variabilidad respectivamente. El consumo comórbido tiene relación con el sexo, el curso escolar,

la cantidad de dinero disponible y la percepción del rendimiento escolar. Conclusiones. El consumo comórbido

de sustancias entre los jóvenes es elevado; no obstante, no en todas las escuelas se constata la misma

prevalencia. Algunas características de las escuelas las colocan en situación de especial riesgo de que el

alumno consuma sustancias. Por ello es importante conocer estas características, para que los programas

educativos sobre drogas y alcohol se ajusten a las necesidades de cada escuela. Se constata la necesidad de

impulsar intervenciones cuyo objetivo sea prevenir el consumo comórbido de sustancias. (Global Health

Promotion, 2012: 19(1): 50-59)

Reflexiones sobre la diversidad cultural en la promoción y la prevención en

materia de salud buco-dental

E. Riggs, C. van Gemert, M. Gussy, E. Waters y N. Kilpatrick

La caries dental es una enfermedad sumamente debilitadora cuyas consecuencias se padecen de por vida. En

casi todos los países desarrollados existen desigualdades importantes en materia de salud buco-dental en las

comunidades menos favorecidas, que incluyen la población refugiada y emigrante. Abordar estas desigualdades

se está convirtiendo en un desafío cada vez mayor, puesto que las comunidades son cada vez más diversas

culturalmente. El conocimiento de las prácticas tradicionales de salud bucodental permitiría a los profesionales

de este campo y del campo de la salud en general entender mejor estas diferencias y, en consecuencia, responder

IUHPE – Global Health Promotion Vol. 19, No. 1 2012

Downloaded from ped.sagepub.com by Pro Quest on April 11, 2012

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Evaluation of The Positive Prevention HIV/STD CurriculumDocumento7 pagineEvaluation of The Positive Prevention HIV/STD CurriculumShenell TolsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Bythenumbers Baltimore City Schools (2011-2012)Documento2 pagineBythenumbers Baltimore City Schools (2011-2012)Shenell TolsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Are Educators Prepared To Affect The Affective DomainDocumento4 pagineAre Educators Prepared To Affect The Affective DomainShenell TolsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation of The Positive Prevention HIV/STD CurriculumDocumento7 pagineEvaluation of The Positive Prevention HIV/STD CurriculumShenell TolsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Taxonomy BloomDocumento6 pagineTaxonomy BloomZainal AbidinNessuna valutazione finora

- Brown PubHlth Catalog (2013)Documento20 pagineBrown PubHlth Catalog (2013)Shenell TolsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Learning Outcomes 2022Documento9 pagineLearning Outcomes 2022emet baqsNessuna valutazione finora

- Marvellous Mangroves Curriculum in BangladeshDocumento29 pagineMarvellous Mangroves Curriculum in BangladeshCLEANNessuna valutazione finora

- Literature 102 - Obedized SyllabusDocumento8 pagineLiterature 102 - Obedized Syllabusapi-312121939100% (1)

- Digitalized IPCRF Form 2020 2021 Final For Master TeacherDocumento17 pagineDigitalized IPCRF Form 2020 2021 Final For Master TeacherJERVIL HANAH THERESE ALFEREZNessuna valutazione finora

- Agricultural Crops Production NC II CGDocumento28 pagineAgricultural Crops Production NC II CGRenato Nator100% (4)

- English K 10 Syllabus 2012 PDFDocumento225 pagineEnglish K 10 Syllabus 2012 PDFCharlotte CookeNessuna valutazione finora

- Dubuc Resume 2015Documento3 pagineDubuc Resume 2015api-263856436Nessuna valutazione finora

- Critique Paper On The Role of Teachers in Curriculum DevelopmentDocumento5 pagineCritique Paper On The Role of Teachers in Curriculum DevelopmentGlen GalichaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nomination Form - Teacher: All Four Sections Must Be CompletedDocumento8 pagineNomination Form - Teacher: All Four Sections Must Be Completedapi-92769782Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chazan2022 PrinciplesAndPedagogiesInJewisDocumento103 pagineChazan2022 PrinciplesAndPedagogiesInJewisDanna GilNessuna valutazione finora

- Key Competencies in EuropeDocumento19 pagineKey Competencies in EuropeTim EarlyNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 2 The Teacher As A Knower of CurriculumDocumento4 pagineModule 2 The Teacher As A Knower of CurriculumJulie Ann NazNessuna valutazione finora

- Mechanical Engineering Program Self-Study ReportDocumento295 pagineMechanical Engineering Program Self-Study ReportCresencio Genobiagon JrNessuna valutazione finora

- School ProspectusDocumento16 pagineSchool Prospectustrena59Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cultural Barriers Native English Teachers EFL ContextsDocumento10 pagineCultural Barriers Native English Teachers EFL ContextsĐỗ Quỳnh TrangNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 3Documento15 pagineUnit 3kinhai_seeNessuna valutazione finora

- P U Student Feedback FormDocumento1 paginaP U Student Feedback FormSanchit ParnamiNessuna valutazione finora

- DIASS DLL Week 2Documento3 pagineDIASS DLL Week 2aireen rose manguiranNessuna valutazione finora

- Ron Resume NewDocumento4 pagineRon Resume Newapi-315120780Nessuna valutazione finora

- Encyclopedia of The Social and Cultural Foundations of Education PDFDocumento1.332 pagineEncyclopedia of The Social and Cultural Foundations of Education PDFPrecious Faith CarizalNessuna valutazione finora

- Pec 9 - Curriculum During PhiDocumento2 paginePec 9 - Curriculum During PhiPrecious Jewel P. BernalNessuna valutazione finora

- KS3 English Curriculum at Brighouse HighDocumento1 paginaKS3 English Curriculum at Brighouse HighzaribugireNessuna valutazione finora

- B - Ed Curriculum 2018 - RevisedDocumento130 pagineB - Ed Curriculum 2018 - RevisedMd SalauddinNessuna valutazione finora

- Prof Ed Set A Answer Key May 13Documento24 pagineProf Ed Set A Answer Key May 13betsy grace cualbarNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 - Fundamentals of Workflow Process Analysis and Redesign - Unit 9 - Leading and Facilitating ChangeDocumento31 pagine10 - Fundamentals of Workflow Process Analysis and Redesign - Unit 9 - Leading and Facilitating ChangeHealth IT Workforce Curriculum - 2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Inglés 1º Medio - Student S BookDocumento181 pagineInglés 1º Medio - Student S Bookjanismore50% (2)

- IT Curriculum Guide Grade 9Documento39 pagineIT Curriculum Guide Grade 9Paul Jaisingh67% (3)

- School Time TableDocumento17 pagineSchool Time TablerajNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching Math in Intermediate GradeDocumento4 pagineTeaching Math in Intermediate GradeBainaut Abdul SumaelNessuna valutazione finora

- To Sir With Love Discourses Positions and RelationshipsDocumento13 pagineTo Sir With Love Discourses Positions and Relationshipsfalland42Nessuna valutazione finora