Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Opium and The Indonesian Revolution

Caricato da

Ugi CilikTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Opium and The Indonesian Revolution

Caricato da

Ugi CilikCopyright:

Formati disponibili

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/248690366

Opium and the Indonesian Revolution

Article in Modern Asian Studies · October 1988

DOI: 10.1017/S0026749X00015717

CITATIONS READS

4 218

1 author:

Robert Cribb

Australian National University

111 PUBLICATIONS 487 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Wild Man from Borneo View project

Genocide View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Robert Cribb on 27 June 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Modern Asian Studies 22, 4 (I988), pp. 701-722. Printed in Great Britain.

OpiumandtheIndonesian

Revolution

ROBERT CRIBB

GriffithUniversity

The Indonesian revolution was a costly affair. Not only was it

accompanied by the extensive destruction of life and property, but the

actual logistics of fighting a protracted revolution placed enormous

financial demands on the new Indonesian Republic, founded on 17

August 1945, three days after theJapanese surrendered, at a time when

the revolutionary government was decidedly ill-equipped to meet

them. The Republic was unable to take over immediately all the

revenue sources of the colonial government and faced major difficulties

in rapidly building up an alternative taxation structure. Needing a

'soft' form of taxation which was easily collected and which did not fall

too obtrusively on the shoulders of its citizens, it turned to opium. The

sale of opium to addicts had been used by colonial governments in

Southeast Asia as a source of revenue, although its importance had

greatly declined in the twentieth century..The Republic, however, not

only maintained the colonial distribution and sales network but

expanded its use of opium to make the drug an important source of

government revenue and, for a time, a major source of foreign

exchange.

Opium has a long history of use in the Indonesian archipelago. It

was subject to a Dutch East India Company monopoly as early ag 1676

and until I894 it was administered, like gambling, by the system of

farming, better known today as franchising. Under this system, the

right to sell opium in a particular region was put out to tender and the

highest bidder was given a monopoly for his region along with the right

to enforce that monopoly with an establishment of spies and hitmen

(Rush 1983, OpiumPolicy 1923: 3-4; ENI III: 158-9). Towards the end

Although this paper is based largely on archival research, much of the information

has been backed or supplemented by interviews in Indonesia and the Netherlands.

Since a number of those interviewed have requested anonymity I have not cited

interview material in the notes which follow. I should like to thank Twang Peck Yang,

Dan Doeppers, Hayden Lesbirel and Greg Weichard for their helpful comments on

early drafts of this paper. Later versions were presented in research seminars at Griffith

University and the Australian National University and the paper has benefited

considerably from the discussion which followed those presentations.

oo26-749X/88/$5.oo + .oo ? I988 Cambridge University Press

701

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

702 ROBERT CRIBB

of the nineteenth century, knowledge of the harmful effects of opium led

to a broad international campaign for the abolition of the opium trade

which was portrayed as morally equivalent to slavery. Within the

Netherlands, an Anti-Opium Bond (Anti-Opium Association) cam-

paigned vigorously against opium, and this pressure, together with a

general rise in the so-called 'Ethical' concern for the welfare of colonial

subjects and an increase in the government's administrative capacity,

led it to limit the farm system in I894 by establishing an Opium-Regie,or

government opium agency, to handle the distribution and sale of

opium. The Regie gradually took over the opium trade from the farm

and by I904 the last of the farms on Java had been abolished, though

they persisted in parts of eastern Indonesia until at least the 1920S

(Rush 1977: 234-300; Elout van Soeterwoude 1890).

Outside these few small areas, the Opium-Regie possessed a full

monopoly of the opium trade in the Netherlands Indies. The cultiva-

tion of opium in the colony was strictly forbidden and the Regie

purchased raw opium from the major producing countries such as

British India, Iran and Turkey, processing it at a factory in the Batavia

suburb of Salemba. Long-time residents of Jakarta can still recall the

scent of opium which met them as they cycled past the factory site (now

occupied by the University of Indonesia) and it is said that swallows

perching under the eaves of the building sometimes fell to the ground

stupefied by the fumes. Refined opium, or tjandoe,was distributed to

addicts through a network of government shops, of which there were

over eight hundred in the I930s and which operated in conjunction

with privately-owned opium dens where addicts could smoke or

consume their purchases. In the nineteenth century, the vast majority

of addicts were Javanese, but by the 1930S their numbers had fallen off

dramatically in response to Indonesian nationalist and Dutch

campaigns against the drug and in response to the rival charms of

tobacco. By the close of Dutch rule, opium consumption had become a

predominantly Chinese vice (Rush I985: 557-9; League of Nations

I942: 31, 6o; Scott I969: I36-7). The Opium-Regie sought energeti-

cally to portray itself as socially progressive by attempting to limit the

spread of the opium habit to previously unaffected areas and by placing

restrictions on its use (Opium policy I923: 5-14; Fowler 1923: 390;

Vanvugt 1985: 361-75). Although the Netherlands Indies government

showed some of the ambivalence of modern governments attempting to

restrict the use of fiscally remunerative drugs such as tobacco and

alcohol-the taxation of addictive drugs is itself somewhat addictive-

it was able to do so because opium was in fact of relatively little

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

OPIUM AND THE INDONESIAN REVOLUTION 703

significance in the overall revenue of the Netherlands Indies. It

provided only I.44% of total revenue in 1938, compared with 6. I 3% in

1930. These figures were amongst the lowest for any territory in

Southeast Asia. Opium sales accounted for a full 23% of government

revenue in the Straits Settlements in 1930 and the figure in 1938 was

still 6.22% (League of Nations 1942: 63).1 The colonial government's

financial reluctance to abolish opium out of hand was supplemented by

tactical considerations. The government argued that opium sales could

not be summarily ended without causing great distress to existing

addicts and thereby introducing the risk that they would provide a

market for illicit opium or for alternative illegal drugs such as cocaine.

The coca bush grew in a semi-cultivated state in several parts ofJava

and its use was held to be much more difficult to control than that of

imported opium. The Salemba factory, therefore, remained in opera-

tion and held significant stocks of raw opium when it fell, along with the

rest ofJava, into the hands of the Japanese in March 1942.

The Opium-Regie appears to have continued its operations under

the Japanese occupation ofJava, though little detailed information on

its activities has come to light. It would be surprising if so useful a

source of revenue had been neglected by the Japanese, for they used it

in Korea and in Manchuria and other parts of China during the Second

World War as a major source of revenue (McCoy 1972: 374; Scott 1969:

I51-I, 174-9). The Opium-Regie's distribution network on Java

therefore appears to have survived the war largely intact, and there

remained some twenty-two tonnes of raw opium and three tonnes of

refined opium in the factory at Salemba, as well as unspecified

quantities of refined opium in Central Java, when the Japanese

surrendered in August 1945. Since this amount represents a little under

the average annual consumption of opium in the immediate pre-war

period, and since the Regie appears to have kept no more than about

two years' supply of raw opium in stock, it can be inferred that

production and consumption of refined opium declined during the

three and a half years of occupation.2 This is probably due to the

occupation government's policy of regional economic autarchy, which

prohibited trade between occupied regions and presumably deprived

the Regie of its former lucrative markets in Sumatra and on the islands

1 Even these Straits Settlements

figures are a far cry from those of the nineteenth

century, when the opium monopoly provided the British government in Singapore with

never less than sixty percent of its total revenue. See Trocki I979: 214.

2

Department van Financien in Nederlandsch-Indie, Opiumfabriek,Jaarverslag over

1938, p. 5 andJaarverslag over 1939, p. 5; League of Nations 1942: 6o.

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7o04 ROBERT CRIBB

of Bangka and Belitung with their large Chinese populations.

The opium factory in Jakarta was of no immediate strategic or

political importance in the immediate aftermath of the surrender and

was probably taken over from the Japanese in September or October

1945, along with the majority of other government offices.3 The

Republic later claimed that it had originally planned to abolish all use

of opium within its territory immediately. Like the pre-war Opium-

Regie, however, it found the financial rewards of dealing with opium in

a controlled way too attractive to ignore. The Republic argued, as the

Dutch had done previously, that opium use could not be abolished

summarily without causing great distress to existing addicts, and

added that the Republic had inherited from its predecessors business

obligations to the Chinese traders involved in servicing the Opium-

Regie and its customers. Since the Republic's claim to independence

rested partly on the argument that it was the legitimate successor to the

Netherlands Indies, its commercial interest in the opium was rein-

forced by a political motive (Nasution I978: 465).

Accordingly, an official Republican Djawatan Tjandoe dan Garam

(Opium and Salt Agency) was established under the authority of the

Ministry of Finance and headed by R. Mukarto Notowidagdo, a former

employee of the agency under the Dutch and Japanese. The Republi-

cans adopted a policy of systematically limiting the sale and use of

opium, but decided, like the Dutch before them, that the best way to

limit opium use was to keep the price high. Thus refined opium seized

from theJapanese in CentralJava was sold, as before the war, through

the network of government-owned shops. WithinJakarta, the Republic

sold refined opium from the Salemba factory both to predominantly

Chinese addicts and to pharmaceutical firms. These sales were

apparently quite open and price rises were recorded in the local

Indonesian press.4

In its personnel, organization and equipment, the Republic's

Djawatan Tjandoe was a direct continuation of the colonial Opium-

Regie. Its place in Republican finances, however, was rather more

3 Dienst der

Algemene Recherche, 'Verantwoordelijkheid van Republikeinse

regeringspersonen voor het in de smokkelhandel brengen van opium' [hereafter

'Verantwoordelijkheidvan regeringspersonen'], 22 February 1949, ARA, Alg. Sec. II,

file I033 (new series); Code telegramme to The Hague, IoJanuary 1949, Alg. Sec. II,

432; Korps Algemene Politie Batavia, Hoofdcommissariat, Proces-verbaal: Raden

Moekarto Notowidagdo, to, I2 August 1948 [hereafter 'Proces-verbaal Moekarto'],

Alf. Sec. II, 432.

Antara (Yogyakarta), 21 February 1946; Nieuwsgier (Jakarta), 8 April I946; Rajat

(Jakarta), 6 February I947.

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

OPIUM AND THE INDONESIAN REVOLUTION 705

important. In the six months to 31 March I946, despite the loss of its

important markets in Sumatra, Bangka and Belitung, the Djawatan

Tjandoe contributed f.8. I million to the Republic treasury, represent-

ing 6.83% of state revenue, more than four times its proportion of

Netherlands Indies government revenue in I938.5

The primary reason for this importance was the Republic's loss of

other sources of income enjoyed by its Dutch and Japanese pre-

decessors. It had no access to the resources, financial or otherwise,

of a metropolitan power, nor, without international recognition, to

international credit facilities. Its administrative structure and the

bureaucratic records necessary for an effective taxation system had

suffered the vicissitudes of the occupation and had received a major

blow early in the war of independence with the outbreak of social

revolutions in many parts of the country. These social revolutions were

frequently accompanied by the wholesale removal of local officials

familiar with and responsible for a range of local taxation. In some

cases their removal was a direct consequence of their tax-collecting

activities on behalf of the Dutch and Japanese (Lucas 1977: 87-122).

The occupation of major ports and administrative centres onJava and

Sumatra by Allied troops in late 1945 created further difficulties. There

was, moreover, a widespread public aversion to all forms of taxation.

The Republic was widely accepted as the legitimate government, but

5

To my knowledge, the only detailed statement of Republican income and

expenditure during the early revolution is that provided in the Dutch document, 'De

financieele crisis van de T.R.I.', i8 May 1946, ARA, AVMK, Verbaal nr. M30, I8

June I946. This document records Republican expenditure in the period from I

October 1945 to 31 March 1946 as follows:

Civil expenditure f. 104. I million

TRI 246.0

Departments and services 49.6

Support funds 18.0

Pensions and relief 3.0

Total f. 420.7 million

Republican revenue in the same period is reported as follows:

Taxes f. 70.0 million

Opium sales 8. I

Salt sales 8.4

Forest product sales 12.0

Petrol and oil sales 15.0

Other 5.0

Total f.I i8.5 million

Note: All figures are in Japanese occupation currency.

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

706 ROBERT CRIBB

that legitimacy did not confer on it the automatic authority even to

collect fares from passengers on Jakarta's tram system. And it could

not, of course, even contemplate resuming the repressive forms of

taxation which had made the Japanese occupation so unpopular, such

as the forced acquisition of produce or the forced recruitment of labour.

Under these circumstances, a number of characteristics of the opium

trade made it a particularly reliable source of income for the Republi-

can government. First, the opium was already in the possession of the

government; it required no complicated or politically damaging pro-

cess of collection. Second, it was relatively easy for the government to

maintain its monopoly over opium as a commodity. The stocks held by

the government were sufficiently compact to allow relatively close

monitoring, while the difficulties of trade and the general economic

depression within the Republic made it unlikely that there would be

large-scale smuggling of opium into Indonesia. Third, opium was a

particularly lucrative good since the government controlled all stages of

production and distribution and, of course, having inherited the opium

from its colonial predecessors, did not even have initial costs to pay.

And fourth, the sale of opium had no internal political consequences,

since opium houses were still a feature of the social landscape and since,

in popular perception at least, most of the addicts were Chinese.

These same characteristics, however, made the Djawatan Tjandoe a

relatively inflexible source of government revenue. Opium was a finite

resource; the government's stocks, although considerable, could not be

replenished. Nor was it possible to engineer a dramatic increase in

consumption. The process of becoming addicted is a fairly long one,

and the vast majority of people now smoked no opium at all. The

government, consequently, could not increase sales without flooding

the market. While the government could and did increase the price of

opium substantially,6 this measure was primarily a response to infla-

tion and was limited by the risk of reduced consumption, substitution

with other narcotics and possibly theft or smuggling. There were,

moreover, political risks involved in being seen to promote opium. The

maintenance of an official opium monopoly was easily defensible

domestically and internationally on the grounds that the public regula-

tion of vice was preferable to uncontrolled illegal operations. The

Dutch themselves only abolished their Opium-Regie in December

I944, while still exiled from the Netherlands Indies, and were thus

hardly in a position to criticise if the Republic did no more than

6

See Ra)jat, 26 July 1946.

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

OPIUM AND THE INDONESIAN REVOLUTION 707

maintain the Regie. To promote opium sales actively, however, was

another thing, for the dangerous effects of opium consumption were by

now almost universally recognised. If the Republic did so, it risked

seriously damaging the responsible reputation it was painstakingly

attempting to build as a prerequisite for international recognition.

That the Republic took the path of expanding opium sales in the face

of these difficulties and risks is a measure of the acute financial pressure

which it faced as the revolution proceeded. This pressure came

principally from the military needs of the revolution. The Republic's

existence was challenged by the Dutch and questioned by the other

Allies, and from late I945, it had adopted a policy of building an

effective army which would guarantee its security while it negotiated

with the Dutch over a formula for recognition and independence. The

task of creating this army (Tentara RepublikIndonesia, TRI) was in the

hands of the defence minister and deputy prime minister Amir Syari-

fuddin and a group of Dutch-trained general staff officers such as Oerip

Soemohardjo and T. B. Sirnatupang. The challenge they faced was not

one of putting men into the field, for the declaration of independence

and the establishment of the Republic had unleashed a wave of

nationalist fervour throughout the Republic and much of the rest of

Indonesia. Tens of thousands of people had joined irregular armed

units which sprang up all over the country to defend independence

against the Dutch. These irregulars made no financial call upon the

Republic; they were locally based and obtained supplies, equipment

and other needs from within their own regions. The problem, from the

point of view of the general staff and the defence ministry, was that

these irregular units were often untrained and poorly armed and, even

more important, that they were difficult to subordinate to Republican

government strategy. The conduct of negotiations and the appeal for

international support by the Republic required truces and ceasefires

from time to time, and irregular units with a strategic view different

from that of the government, or with no strategic view at all, were an

embarrassment. The government wanted an army which could fight

effectively but which could also be relied upon to refrain from fighting

when that was necessary (Sundhaussen 1982).

The creation of such an army was expensive and demanded new

sources of finance. For, although there were army units and some

irregulars which readily accepted the authority of the general staff,

many would not do so without the added incentive of the logistic

support which military organizations are usually expected to provide to

their lower echelons. Thus during the six months from October I945,

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

708 ROBERT CRIBB

covering approximately the first six months of the army's formal

existence, the Republic spent f246.o million in Japanese occupation

guilders, 58% of its total government expenditure, on the TRI. By

contrast the budget for the Netherlands Indies department of war in

1936 was a mere 13.85% of the total budget.7 The money, it appears,

was not closely controlled by the general staffor the ministry of defence,

but rather was issued to reliable senior officers in the regions who had

the discretion to use it either to establish their own authority as regional

commander or, more often, to strengthen army units already regarded

as disciplined and loyal. The West Java Siliwangi Division of Colonel

A. H. Nasution was one of the main beneficiaries of this kind of grant.

Expenditure on this scale put enormous financial strain on the

Republic. During the six months when the TRI budget was f.246.o

million, total central government revenue was no more than f. I I8.5; the

balance was made up by spending stocks of occupation currency and

pre-war Netherlands Indies currency inherited from the Japanese.

This source was clearly limited, was politically unedifying and had

undesirable economic effects such as encouraging inflation. As already

described, however, the Republic faced major difficulties in generating

regular income through taxation. The Republic was able to collect a

certain amount of money through highly publicized national loans, and

after the issue of Republican currency (ORI) in October I946 it could

print its own finance (Cribb I981: 127, I33). Both these techniques,

however, had severe practical limitations and the Republic needed

increasingly desperately to obtain a new source of revenue.

The financial crisis created by the need to give priority to military

expenditure was felt with particular acuity in the city ofJakarta and it

was here that the Republic first moved into the imaginative use of

opium as a source of finance. Although Jakarta had effectively been

occupied by the Dutch and British from early I946, the Republic

retained not only a number of central government offices in the city but

also a full municipal government as a demonstration of its claim to the

nation's capital. The financing of this establishment was always a

problem for the Republic. The independent income of the municipal

administration was based largely on a few market taxes and on sales

from municipal fishponds (Cribb I984: 107). The other offices had no

source of finance and were dependent on boxes of money dispatched by

the Republican government in Central Java. The Republican general

hospital in Jakarta, on the other hand, which happened to stand next

7 'De financieele crisis van de T.R.I.', loc. cit.; Pocket Edition of the Statistical Abstract of

the NetherlandsIndies i940, 132.

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

OPIUM AND THE INDONESIAN REVOLUTION 709

door to the opium factory in Salemba, was apparently able to support

itself with relatively little financial call on the Republican government.

This was partly because it was able, unlike other Republican govern-

ment bodies, to charge a fee for service, but it also appears to have

obtained cash by selling opium both to addicts and to pharmaceutical

firms in Jakarta. Small amounts of opium also made their way to the

Lasjkar Rakjat Djakarta Raya (People's Militia of Greater Jakarta), the

main non-government resistance group in the countryside east of

Jakarta, but it is not possible to tell whether this was intended for

medical or for financial purposes.

It appears that the opium sold came from the existing refined stock,

and that the opium factory was not in operation during this period, for

it was amongst a number of buildings which the Dutch requested from

the Republic in October I946 on the grounds that they did not appear

to be being used. The transfer in fact was not made, but the request

prompted a group of medical students from the hospital to take steps to

ensure that the opium would not fall into Dutch hands. In late

November or early December I946, they arranged for the machinery,

personnel and stocks of the opium factory to be transported by train

from Jakarta to Central Java. The opium was put under armed guard

and was probably carried aboard the special diplomatic trains which

travelled regularly between Jakarta and Yogyakarta and which were

relatively free from inspection by Dutch and Republican border

guards. The arrival of the machinery in Central Java enabled the

Djawatan Tjandoe to commence refining opium for its own trade.8

Stocks of refined opium remained in Jakarta for sale to addicts, but

these sales appear to have been under the control of the Republican

health department, rather than the Djawatan Tjandoe, for it was the

health department which announced on 30 July I947 that sales would

be wound down and eventually stopped. Sales in fact continued until at

least September I947, well after the Dutch had taken over all Republi-

can establishments inJakarta except for the hospital and its associated

buildings.9

The transfer of opium stocks to Central Java allowed the central

government to use it notjust for local purposes but as part of its export

drive. Since early 1946, the Republic had made a determined effort to

revive the export trade which was the mainstay of the Netherlands

Indies economy and which had been one of the principal attractions for

8

Berita Indonesia (Jakarta), 5 October 1946; Ra'at (Jakarta), 26 July 1946, Sejarah

kesehatannasional Indonesia vol. I 1978: 93, 99.

9 Berita

Indonesia, 8, 30July 1947; Star Weekly (Jakarta), 21 September 1947.

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7IO ROBERT CRIBB

the invadingJapanese. One of its first ventures along those lines was a

proposal in April I946 by the republican prime minister Sutan Syahrir

to supply India with halfa million tons of rice in exchange for a variety

of goods, especially Indian cotton cloth, which was then in very short

supply onJava (Cribb I984: I55-7). This was followed in the course of

I946 by an expansion in the export of plantation products from Java.

Rubber and sugar appear to have been the main crops exported, but

other products such as tobacco, kapok, quinine and vanilla were also

included. Vessels, often owned by Chinese businessmen from

Singapore, typically collected cargoes in Cirebon, Tegal or Pro-

bolinggo and sailed via Palembang in Sumatra to Singapore (Overdij-

kink 1948: 51-3).

This export trade gave the Republic access to goods such as

weapons, bicycles, tyres, medicines and cloth which were invaluable,

both in its conduct of the war and in enabling it to maintain a basic level

of public welfare. The trade also gave the Republic an important means

of reinforcing its authority, though its importance was somewhat

diminished by the fact that the Republic by no means controlled the

machinery of import and export. There were many organisations other

than the Republic engaged in the trade. Of Indonesian goods entering

Singapore, the largest percentage by far came from Sumatra where it

was controlled by regional strongmen such as Dr A. K. Gani of

Palembang who, while they recognised the formal authority of the

Republic, were free to do as they wished within their own fiefs. Of the

goods from Java, many were exported not by the central government

but by local army commanders who, operating in association with

Chinese businessmen, were attempting through trade to make up for

the shortage of funds from official sources.

The suspected presence of weapons in the cargo of ships trading to

the Republic, and the fact that the trade clearly helped to consolidate

the power of the Republic led the Dutch to attempt to stop the trade. In

January 1947, the Netherlands Indies government announced a ban on

the import of military and semi-military goods and on the export of

products from plantations formerly owned by Dutch or other foreign

investors. Although bans were imposed primarily for strategic reasons,

the basis of the ban on export of plantation products was the Dutch

refusal to recognise the expropriation of their plantations by the

Japanese and the Republicans. To enforce the ban, the Dutch

instituted extensive naval patrols in the Straits of Malacca and theJava

Sea (Overdijkink I948: I52). The Republic responded to this restric-

tion by beginning to do business with an American firm, Isbrandtsen &

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

OPIUM AND THE INDONESIAN REVOLUTION 7II

Co. The Republic and the company later signed a contract under which

the company would act as the Republic's agent .. the transport and

sale of Republican goods and the use of the proceeds to buy American

goods. Both parties appear to have expected that the involvement of an

American firm would lead the United States State Department to

intercede with the Dutch in order to have the ban lifted. This proved a

forlorn hope, and when the Dutch seized an Isbrandtsen ship, the

Martin Behrmann, in February I947 on charges of illegally exporting

rubber, the State Department failed to give effective support to the

company (Homan 1979; Homan I983: 126).

Although it was possible for the export trade to continue on a

reduced and clandestine scale, using a multitude of small fishing boats

and the like, the Dutch blockade faced the Republic with a financial

crisis. Without that trade, the Republic could not maintain its govern-

ment and army in the face of the Dutch; nor could the government

easily maintain its effective authority over its own people, especially the

independent-minded regional military commanders. The financial

crisis was all the more severe because the Republic now had desperate

need of foreign exchange. During 1946 Republican leaders, especially

Syahrir, had made sustained efforts to reach a political compromise

with the Dutch, involving a few constitutional changes and a short

postponement of full independence on the part of the Republic in

exchange for Dutch recognition. It was the presence of the British

which had originally brought both sides to the negotiating table, and

the continued presence of British troops in Java until November 1946

helped to keep negotiations going through a number of serious dif-

ferences of opinion, but both Syahrir and the Netherlands Indies

Lieutenant Governor-General H. J. van Mook appear to have

genuinely been aiming for a settlement acceptable to both sides. The

resulting Linggajati Agreement was initialed in November 1946, but

soon became a dead letter in the face of persistent breaches of the spirit,

if not the letter, of the agreement, such as the Dutch blockade and

Republican skirmishes across the ceasefire line.

As relations worsened in the early months of 1947, the Republican

government realised the urgent need to marshal international support

which might restrain the Dutch from attempting a military solution to

their problems. The Republic accordingly established quasi-diplo-

matic offices in London, Washington, New Delhi, Bangkok and

Singapore from which to coordinate the international campaign.

Neither Japanese occupation currency nor the newly issued Republi-

can currency had any value abroad. To maintain its quasi-diplomatic

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7I 2 ROBERT CRIBB

establishments, therefore, the Republic needed hard currency, and to

obtain that it had, like all governments, to sell its goods on the

international market.

Unable, because of the blockade, to sell its previous staples such as

rubber and sugar, the Republic turned to opium and began to sell its

stocks actively and extensively outside the distribution apparatus of the

Djawatan Tjandoe. Two characteristics of opium made it a particu-

larly attractive proposition for the beleaguered Republican govern-

ment. It was light and it was valuable; by weight opium is one of the

most valuable of substances, and it was thus eminently suited to the

clandestine trade which the Republic had to adopt to circumvent the

Dutch blockade. There were other goods in this class-vanilla,

quinine, gold and jewels-and these were all traded by the Republic.

Their quantities, however, were limited, none was subject to an official

government monopoly, and all posed some problem of collection. Small

quantities of opium had been distributed outside the Djawatan

Tjandoe since early in the revolution. Republican leaders used it as a

means of payment for services rendered when for some reason or other

it was thought desirable to keep the payment out of official records.

Until the second quarter of I947, however, the amounts involved in

these transactions seem to have been small and their purposes

peripheral to the Republic's programmes. The primary value of opium

to the Republic continued to be the revenue it generated through the

official sales network.10

The first sign of a major alteration to this policy came with the

allocation of eighty kilos of raw opium to an official of the B.T.C.

(Banking and Trading Corporation), a Republican government-spon-

sored agency, in May 1947.11 The size of the allocation was significant,

as was the fact that it was recorded at all. As long as the quantities of

opium being distributed outside the auspices of the Djawatan Tjandoe

were small, there was no pressing need to record them. This was all the

more the case if grants of opium were being used as a way to avoid

recording a cash transaction. The grant to the B.T.C., on the other

hand, was large and was not delivered for services rendered but rather

as a contribution to the organisation's budget.

The Republic exercised no further control over opium distributed in

10

'Verantwoordelijkheid van regeringspersonen', loc. cit; 'Proces-verbaal Moe-

karto', loc. cit.; Nieuwsgier,13 May 1946. See alsoJ. G. Reyers, 'Rapport omtrent mijn

ervaringen als veroordeelde in het Huis van Bewaring Struiswijkgedurende de periode

3 Februari I948-3 Mei I948', 7 May 1948, ARA, Proc.Gen., file 793.

11 'Verantwoordelijkheid van regeringspersonen', loc. cit.; on the B.T.C., see Sutter

I959: 443-5.

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

OPIUM AND THE INDONESIAN REVOLUTION 713

this fashion, though it is highly likely that most found its way to

Singapore along with other cargoes handled by the B.T.C. The

government would have had no wish to see the profitable monopoly of

the Djawatan Tjandoe within the Republic breached, and may even

have required that the opium be exported. It was, however, not until

the government of Amir Syarifuddin came to power on 3July I947 that

the Republic formally decided to sell opium abroad. The immediate

reason for this decision appears to have been the impending departure

of the recently displaced prime minister Syahrir for the United

States, where he was to plead the Republic's case in the United

Nations. This mission was bound to put further strain on the foreign

exchange position of the Republic. The fact, however, that Syahrir was

flying out under quasi-diplomatic immunity accompanied by the

Australian representative Tom Critchley meant that the party could

afford to take along a quantity of opium and quinine to fund the

mission; Syahrir nonetheless took the precaution of bringing along a

medical doctor, Dr Abdul Halim, later a prime minister of the

Republic, who could claim if necessary that the goods were for medical

purposes only.'2 The opium was apparently to be delivered to the

Republic's representative in Singapore, who would sell it and provide

Syahrir with the necessary funds to continue his journey.

The circumstances which had brought the Republic to use opium for

internal budgetary purposes and to finance its foreign establishments

were exacerbated within a few days ofSyahrir's departure by a massive

Dutch military attack on the Republic, known as the First Police

Action. In this attack the Dutch seized large areas ofJava, including

the most important plantation areas of West and East Java. Not only

did the Republican government now have to operate on a considerably

more slender economic base, but the clandestine trade in products such

as tobacco which Republican territory still produced became more

difficult because the Republic controlled only a relatively short stretch

of the northern coast ofJava. There was widespread speculation, too,

on the possibility of another Dutch attack, and the Republic thus faced

an even more urgent need to consolidate and strengthen its army and to

present as effective as possible an international campaign in its own

favour.

Opium was used in the first place as a direct source of finance. This

was a direct extension of the existing role of the Djawatan Tjandoe,

although other senior officials of the finance ministry were also

12 Code

telegram to The Hague, Io January I949, loc. cit.; Halim I98I: 58-60.

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

714 ROBERT CRIBB

involved. The Djawatan now not only supplied refined opium to

consumers through its shops but also supplied specific quantities of raw

opium from its warehouses in Yogyakarta to opium traders inJepara,

one of the few ports on the northern coast of Java still in Republican

hands. The traders, mostly Chinese, paid for the opium at a rate of one

kilogramme of 20 carat gold for 6? kilos raw opium, and then shipped it

by fishing boat to the Dutch-occupied city of Semarang. If a Dutch

naval patrol approached, the opium, packed in small tins and wrapped

in rubber sheets, was suspended overboard at the end of a piece of rope

until the danger had passed. Other traders transported the opium on

horseback through the mountains down to Semarang, packed in tins of

tobacco in order to mask the smell of the opium. In EastJava coffee was

used for the same purpose. According to a Dutch report based on

Republican documents, some 597.85kg of raw opium and 62,500 tubes

of refined opium (each tube approximately o.8g) were disbursed by the

Djawatan Tjandoe in Yogyakarta in the period from July 1947 to

January I948. The volume was sufficient to cause the sale price in

Semarang, Cirebon andJakarta to drop from f.8,ooo to f.4,ooo (Nether-

lands Indies currency) per kilo.13 Some of this opium was presumably

consumed onJava, but much of it was sent on to Singapore, concealed

in an ingenious variety of hiding places, ranging from coffins to false-

bottomed kerosene drums.

During the second half of 1947, increasingly large amounts of opium,

both raw and refined, were supplied to senior government officials not

on the staff of the Djawatan Tjandoe. They included the minister of

finance, A. A. Maramis, who increasingly took an active role in

supervising the opium trade. It was apparently intended that these

men should use their personal contacts and the special opportunities

they enjoyed by virtue of their positions to sell a larger volume of opium

than could be handled by the Djawatan. Their probity was said to be

guaranteed, if necessary, by the fact that they all owned property in the

Republic which could be confiscated if they absconded.14 Early in 1948,

however, Maramis recruited the services of a dashing young Chinese

Indonesian footballer called Tony Wen. Wen was associated with the

Indonesian Nationalist Party (P.N.I.) and he was a leader of the so-

called International Brigade, a multinational irregular unit founded in

Yogyakarta during the revolution. It was modelled vaguely on the

13

Dienst der Algemene Recherche, 'Opiumsmokkel van Republikeins naar Neder-

lands gecontroleerd gebied', 30 July 1948, Proc.Gen. 375; 'Verantwoordelijkheid van

regeringspersonen', loc. cit.; 'Proces-verbaal Moekarto', loc. cit.

4 'Proces-verbaal

Moekarto', loc. cit.

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

OPIUM AND THE INDONESIAN REVOLUTION 715

International Brigades which fought in the Spanish Civil War and was

composed of Indians, Arabs, Chinese and other foreigners sympathetic

to the Revolution. Wen's principal credentials, however, appear to

have been his contacts with Chinese businessmen in Singapore, for this

opened to the Republic the possibility of trading directly to Singapore,

bypassing the middlemen and glutted markets of Jakarta and

Semarang.15 In early March 1948, accompanied by an official of the

Djawatan, Wen took five hundred kilos of raw opium from Tuban in

East Java by speedboat to Singapore, sold it, and presented the

Republic's representatives with $225,000 in Straits currency. Part of

the money was returned to the Republic through Jakarta and part was

used to finance nationalist operations overseas.16

Maramis had reportedly stipulated that the Republic should receive

$450 per kilo, which left Wen's payment short by some $900,000. The

money, nevertheless, was vastly more than anything the Republic had

previously received from its opium transactions, and it emboldened

Maramis to use Wen on an even more daring venture. Part of the

proceeds were used to purchase the services of a group of Australian

and British adventurers who were commissioned to fly a Catalina

loaded with two and a half tonnes of opium from Lake Campurdarat

near Kediri in East Java to Singapore. Wen met the plane where it

landed on the sea of Singapore and oversaw the deal at the Singapore

end. In May, June and July 1948 three such flights were made and

some eight tonnes of raw opium was transported to Singapore, some of

it being sold through agents other than Wen. The Australians also flew

to Thailand, where they picked up cargo for the Republic, especially

tyres, which they brought with them on flights into Indonesia. They

apparently made flights to Bukit Tinggi in West Sumatra as well, to

transport opium for the government there.17 The purpose of these

shipments to Sumatra was probably not primarily to bolster the

authority of the central government there, for even the five tonnes of

opium sent would count for little against the economic power of the

15

Suryadinata 1978: 188; File: Tonny (sic) Wen, Proc.Gen., 820; 'Verantwoordelijk-

heid van regeringspersonen', loc.cit.;C.M.I. Document no. 5419, MvD/CAD, HKGS-

NOI, Inv.nr. GG56, 1948, bundel 6323D.

16 'Proces-verbaal

Moekarto', loc.cit.; 'Verantwoordelijkheid',loc.cit.;C.M.I. Docu-

ment no. 5746. MvD/CAD, HKGS-NOI, Inv.nr. GG55, I948, bundel 6323B, p. I.

17 'Proces-verbaal Moekarto', loc. cit.; codetelegram aan Den Haag, IoJanuary 1949,

loc. cit.; Consulate-General of the Netherlands, Singapore, to Director, Malayan

Security Service, 3 August 1948, Alg. Sec. II, 107; 'Relaas van de ervaringen,

opgedaan tijdens de vluchten met de Catalina PBY5-RI-oo5 gedurende een periode

van 21 maand', n.d. [December, 1948], C.M.I. Document no. 5685, MvD/CAD,

HKGS-NOI, Inv.nr. GG58, 1948, bundel 6323H.

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7I6 ROBERT CRIBB

strongmen who controlled the rubber trade across the Straits of

Malacca. Rather it was probably a precautionary measure intended to

guarantee that the Republican central government would have a

reliable source of finance if it were suddenly forced by another Dutch

military action to evacuate to Sumatra. It was apparently the

Australians, too, who piloted the aircraft which brought the communist

leaders Musso and Suripno back to Indonesia in August I948.18

Despite Tony Wen's initial brilliant success with the trade to

Singapore, by the end ofJuly 1948, severe problems had begun to arise.

Large quantities of opium had been delivered but very little of the

payment had been received. Tony Wen received another two and a half

tonnes of opium in June which he apparently never paid for; from the

other opium traders with whom the Republic dealt came no more than

$132,000 in payment for opium valued at $1,575,000. Sales in Jakarta

were a good deal more reliable, and those proceeds went a considerable

way towards defraying the heavy costs of maintaining a large Republi-

can establishment in Jakarta for continued negotiations with the

Dutch. Even there, however, there was a major gap between what was

owing and what had been received.19

It was to ensure that this kind of abuse of the system was limited that

the Republic had appointed Mukarto, as head of the Djawatan

Tjandoe, to be its financial coordinator for Australia and Southeast

Asia, excluding Indonesia itself. Since such a designation, however,

would have made Mukarto at least as suspect from the Dutch point of

view as his position in the Djawatan, he was accredited to the

Republican delegation in Jakarta as a journalist. This delegation

enjoyed a quasi-diplomatic status in Jakarta while it undertook nego-

tiations with the Dutch over the implementation of the Renville

Agreement, signed between the Republic and the Dutch in January

1948. This accreditation not only gave Mukarto a clear reason for

frequent travel between Yogyakarta, Jakarta and Singapore but gave

him a degree of quasi-diplomatic immunity from customs and security

inspection.20

18

'Relaas van de ervaringen', loc. cit.; Soerjono I980: 78. According toJohn Coast,

another pilot working for the Republic, and probably also for British intelligence, it was

not the Australians but yet another pilot who carried Musso and Suripno. See Coast

1992: 157.

'Proces-verbaal Moekarto', loc. cit.; Code telegram to The Hague, o January

1949, loc. cit.; Soebeno (official, ministry of finance), to minister of finance, 15

September 1948, C.M.I. Document no. 5350, MvD/CAD, HKGS-NOI, Inv.nr.

GG56, I948, bundel 6323C.

20

'Verantwoordelijkheidvan regeringspersonen', loc.cit.; N.E.I. Government Press

Release, I6 August 1948, Alg. Sec. II, 432.

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

OPIUM AND THE INDONESIAN REVOLUTION 717

For some time, however, the Dutch authorities had been concerned

by the abundance of illicit opium circulating in their territory and they

were engaged in energetic efforts to track down those responsible. On

30 July I948, Dutch police in Jakarta arrested one of the Djawatan

Tjandoe's Chinese agents and discovered in his possession documents

suggesting strongly that Mukarto was involved in the trade. He was

subsequently arrested inJakarta on Io August as he was about to board

an official aircraft for Yogyakarta. With this the network of Republican

opium sales began to unravel as the Dutch arrested more Djawatan

agents. Maramis, himself a member of the Republican delegation, left

somewhat rapidly for the Unitd States on a diplomatic mission. The

Dutch announced new restrictions on the activities and freedom of

movement of the delegation and took the opportunity to announce the

expulsion of a large number of Republican representatives. Few, if any,

of these had any involvement in the opium trade but most were engaged

in some kind of activity which the Dutch considered undesirable or

subversive, and the order expelling them was merely an attempt to

exploit the blow to the Republic's international prestige which the

exposure was expected to produce.21 The evidence which the Dutch

had collected, however, fell a good way short of incontrovertible proof

of the Republic's dealings in opium, and the Republic was able to

weather the storm which followed to a considerable degree simply by

vociferous denial of complicity and demands for proof. It admitted to

having continued the activities of the Opium-Regie, but it claimed to

have done so on a vastly reduced scale and to have announced that all

trade in opium would be forbidden from 31 December I948 (Coast

1952: I77-84; Nasution I978: 465-7). The fact that the Republic's

opium stocks lasted so long despite the Republic's overseas sales

initiative indicates that the Djawatan Tjandoe was selling far less

opium through conventional channels than had the pre-war Opium-

Regie. This is probably due largely, however, to its inability to reach

the Dutch-controlled regions which had been the Regie's most lucra-

tive markets.

Mukarto's arrest and the publicity which followed it effectively

ended the Republic's venture into the international opium trade. Its

chances of even recovering some of the money owed to it by its business

partners in Singapore disappeared when Tony Wen was arrested by

the British in September 1948 on suspicion of involvement in weapons

smuggling in Malaya. He was released before the Dutch could set in

21 N.E.I. Government Press Release, i6 August I948, loc. cit.; code telegram to The

Hague, io January 1949, loc. cit.

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7I8 ROBERT CRIBB

train extradition procedures against him, but decided to depart while

he could and disappeared to China. In nearly every sense, the

Singapore venture was a disaster. Apart from the non-payment of

money due, it cost the Djawatan Tjandoe around one-quarter of its

original stock, assuming that the consignment from Salemba had

formed the bulk of the Republic's opium supply; Mukarto's statement

to Dutch police in August 1948, after his arrest, that only 5.4 tonnes was

left over is likely to be more or less accurate.22 By selling in bulk and by

selling raw rather than refined opium the Republic had foregone the

price advantages enjoyed by the Djawatan Tjandoe sales. Since

Singapore, moreover, was the ultimate destination for much of the

opium smuggled by land and sea into Dutch-occupied regions ofJava,

it contributed indirectly to flooding that more reliable market. And it

was only by good fortune and fast talking that the Republic escaped a

major diplomatic setback when its activities were discovered. Only the

fact that the Republic had needed a large amount of money rapidly in

order to finance its international campaign made the venture worth-

while. Thereafter it was able to make do with the proceeds of the less

spectacular smuggling trade into Dutch territory. It also appears that it

had somewhat greater access to proceeds from the smuggling of rubber

from Sumatra to Singapore.

To an increasing extent as I948 wore on, the Republic made direct

disbursements of opium to the armed forces, which once more faced a

heightened risk of a Dutch attack. The earliest recorded provision of

opium to the armed forces was a consignment of ninety kilos of raw

opium to the airforce in May 1948, which was to be flown to the

Philippines and sold there. Therefore, between June and October,

some I58,900 tubes of refined opium were provided to the ministry of

defence and were distributed to a wide variety of military salesmen who

were instructed to exchange it for money or equipment. The chief

recipient of the opium, however, was the Siliwangi Division, which had

been evacuated to Republican territory from West Java after the

Renville Agreement of January I948 under which the Republic had

recognized Dutch authority in territories conquered during the First

Police Action. The division had been reconstituted as a mobile strike

22

'Proces-verbaal Moekarto', loc.cit.; File: Tonny Wen, loc.cit.;Dagelijks Overzicht

Belangrijkste Inlichtingen no. 786, 17 November 1948, Proc.Gen., 44; R.I. Ministry of

Defence, 'Verantwoording van ontvangen en afgeleverde opium', 23 October 1948,

C.M.I. Document no. 5641, MvD/CAD, HKGS-NOI, Inv.nr. GG57, 1948, bundel

6323F; Mr G. P. Kies (ministerie van overzeese gebiedsdelen), Ontwerp-publicatie

[hereafter 'Ontwerp-Kies'], 15 March 1949, MvD/CAD, Kabinet van de Legercom-

mandant Indonesie, doos 5, bundel 43.

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

OPIUM AND THE INDONESIAN REVOLUTION 7I9

force, and one of its principal tasks was to reinfiltrate Dutch-occupied

West Java as part of a broad campaign to prevent the Dutch from

maintaining security and order. For this the Siliwangi needed re-

supply and re-equipment beyond the financial capacity of the govern-

ment. The Hatta government also had a political motive in directing

support to the Siliwangi Division, since it was one of the government's

strongest supporters within the army against units allied to the deposed

left-wing prime minister Amir Syarifuddin. It was said that sixty tubes

of opium would buy forty yards of Chinese cotton cloth, twenty-five

tubes a rifle and two hundred a bren gun. So important was the supply

of opium to the army that the ministry of defence made available one of

its weapons factories for the manufacture of the tubes in which refined

opium was packed.23

The distribution of opium tubes within the Republic carried no

significant political risk and restored to the Republic the commercial

advantages of dealing in refined opium. The scale of opium distribution

within the Republic, however, and the need for even official operators

to act clandestinely made it almost inevitable that quantities of opium

would go astray. The ministry of finance issued formal licences to those

who had received opium legitimately, but it was a continual source of

frustration for the Republican police that their efforts to track down the

source of apparently illicit opium frequently ended with the discovery

that the suspected dealer held a finance ministry licence or was an

agent of Republican military intelligence. The police also discovered a

good deal of laxity in the way in which opium was distributed and

concluded that corruption was rife in the Djawatan Tjandoe. Most of

the stories which still circulate of army officers in CentralJava engaged

in small-scale opium dealing are probably the result of transactions

between those officers and their local Djawatan Tjandoe opium house,

rather than the larger dealings of the agency. Maramis promised to

tighten the licensing process, but there is little evidence to suggest that

anything practical was done to limit the volume of opium in circula-

tion.24 Although no figures exist to confirm it, it is likely that the extent

23

'Ontwerp-Kies', loc. cit.; 'Verantwoordelijkheid van regeringspersonen', loc. cit.;

Lt.-Col. Suprajogi (Head of Intendance, TNI) to head, Central Weapons Bureau, 13

July 1948, C.M.I. Document no. 5644, MvD/CAD, HKGS-NOI, Inv.nr. GG57, 1948,

bundel 6323F; Suprajogi to Hatta, 15 September 1948, C.M.I. Document no. 5518,

MvD/CAD, HKGS-NOI, Inv.nr. GG57, 1948, bundel 6323E; C.M.I. Document no.

5299, MvD/CAD, HKGS-NOI, Inv.nr. GG56, 1948, 6323C.

4 Maramis to Soekanto (Head of

Republican State Police), 2 March 1948, C.M.I.

Document no. 5746, p. 1; MvD/CAD, HKGS-NOI, Inv.nr. GG55, 1948, bundel

6323B; Soekanto to Maramis, 12 March 1948, ibid., pp. I8-I9; Mohamad

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

720 ROBERT CRIBB

of private trading in opium had a significant effect on Djawatan

Tjandoe sales.

These problems and transactions were recorded in considerable

detail in files and archives in the Republican capital of Yogyakarta and

this information was amongst the mass of material which fell into

Dutch hands in their Second Police Action in December 1948. Cap-

tured Republican documents, translated by the C.M.I. (CentraleMili-

taire Inlichtingendienst,Central Military Intelligence Service), form the

basis for much of our knowledge of the opium trade, particularly from

I947. The documents appeared to be a propaganda windfall for the

Dutch, for they were now in possession of documents of indisputable

authenticity which proved not only the Republic's involvement in

opium trading but indicated that knowledge of the trade went up at

least as far as the prime minister and vice-president, Mohammad

Hatta, whose signature appeared on a number of incriminating docu-

ments. An official of the Dutch ministry of overseas territories immedi-

ately began to digest the documents in order to produce a report for

publication in English and Dutch. The report was ready by March

1949 but was never published or released, not because it was insubstan-

tial but because it was too damning. The Dutch government, under

intense pressure from the United States to reach an agreement with the

Republic, wanted to deal with what it saw as the more moderate

elements in the Republic, yet it was precisely these elements, exempli-

fied by Hatta, who had responsibility for the trade. The report was

quietly shelved and disappeared from sight.25

The Dutch attack and the subsequent guerrilla war ended for a time

the Republic's central control over what remained of its opium supply.

Local stocks were probably used by local military commanders, though

there is no documentary evidence of this. Opium stocks amounting to

perhaps four tonnes were captured by the Dutch in the attack on

Yogyakarta and in subsequent mopping-up operations. According to a

Dutch report, some Indonesian Chinese associates of Mukarto

approached the Republican government in August 1949 with the

suggestion that stocks of opium held in various parts of Java should

once again be shipped to Singapore to bolster the Republic's finances

Soerjopranoto (Police Chief, Yogyakarta) to Maramis, 20 March 1948, ibid., pp. 20-3;

Maramis to Soekanto, 29 May 1948, ibid., p. 26; Dienst van de Staatspolitie, afd.

P.A.M. teJogjakarta, Report, 27 May I948, ibid., pp. 42-3.

25

Maj.-Gen. D. C. Buurman van Vreeden (Chief of Staff, KNIL) to Lieut.-Gen.

S. H. Spoor (Commander, KNIL), 2I March I949, MvD/CAD, HKGS-NOI, Inv.nr.

GG57, 1948, 6323F; Spoor to Buurman van Vreeden, 22 March 1949, ibid.

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

OPIUM AND THE INDONESIAN REVOLUTION 721

abroad.26 There is also a report that a consignment of 1,500 kilos was

sent to Singapore by ship in July I949 under the auspices of the

ministry of finance. In the absence of any corroboration, it is difficult to

rely upon these reports. The first is particularly questionable, since the

Chinese involved included one of the dealers who still owed the

Republic $573,000 from his previous transaction. Nevertheless it is by

no means impossible that the sales took place and they would have

involved no innovation in Republican policy.

The opium transactions of the Indonesian Republic made a signifi-

cant contribution to its struggle against the Dutch in the years 1945 to

I949. The Republic inherited and maintained the opium monopoly of

the colonial government and was able to use it as a reliable source of

substantial revenue early in the revolution when other revenue sources

had become unviable or irregular. Later in the revolution the Republic

sold opium on an extensive scale outside its own borders. Its attempts

to sell opium direct to traders in Singapore was spectacularly unsuc-

cessful in a commercial and political sense but provided the Republic

with urgently needed foreign exchange at a crucial period in its struggle

for independence. It is ironic that opium, so closely associated with the

rise of European power in Asia, should also have contributed to its

defeat.

26

'Republikeinse wapentransacties met het aangrenzende buitenland', C.M.I.

Signalement no. 9573, Alg. Sec. II, 766/I.

References

Coast, John. I952. Recruit to Revolution: Adventure and Politics in Indonesia. London:

Christophers.

Cribb, Robert. I98I. 'Political Dimensions of the Currency Question, 1945-I947.'

Indonesia 31: 113-36.

--. I984. 'Jakarta in the Indonesia Revolution, 1945-I949.' Ph.D. dissertation,

University of London.

Elout van Soeterwoude, W. 1890. De Opium-Vloekop Java. The Hague: Anti-Opium

Bond.

Encyclopaedievan NederlandschIndie Vol. 3. 19I9. The Hague: Martinius Nijhoff.

Fowler, John A. 1923. Netherlands East Indies and British Malaya: a Commercial and

Industrial Handbook. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Halim, Abdul. 98 . Di Antara Hempasan dan Benturan: Kenang-Kenangan.Jakarta: Arsip

Nasional Republik Indonesia.

Homan, Gerlof D. 1979. 'The Martin Behrmann Incident.' Bijdragen en Mededelingen

Betreffendede Geschiedenisder Nederlanden90: 253-70.

--. I983. 'American Business Interests in the Indonesian Republic, 1946-1949.'

Indonesia 35: 125-32.

League of Nations, Advisory Committee on Traffic in Opium and other Dangerous

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

722 ROBERT CRIBB

Drugs. 1942. AnnualReportsof Governments on the Trafficin Opiumand otherDangerous

Drugsfor theyear 1939. Geneva: League of Nations.

Lucas, Anton. 1977. 'Social Revolution in Pemalang, CentralJava, 1945.' Indonesia 24:

87-I 22.

McCoy, Alfred W. I972. ThePoliticsof Heroinin Southeast

Asia. New York: Harper and

Row.

Nasution, A. H. 1978. SekitarPerangKemerdekaan Indonesia,Jilid 7: PeriodeRenville[On

the Indonesian War of Independence, Vol. 7: the Renville Period]. Bandung:

Angkasa.

The OpiumPolicy in the NetherlandsIndies. I923. The Hague: Government's Printing

Office.

Overdijkink, G. W. I948. Het IndonesischProbleem:Nieuwe Feiten. Amsterdam:

Keizerskroon.

PocketEditionof the StatisticalAbstractof the NetherlandsIndies. I940. Batavia: Central

Bureau of Statistics.

Rush, James R. I977. 'Opium Farms in Nineteenth-Century Java: Institutional

Continuity and Change in a Colonial Society, I86o-I9o0.' Ph.D. dissertation, Yale

University.

-- . 1983. 'Social Control and Influence in Nineteenth Century Indonesia: Opium

Farms and the Chinese ofJava.' Indonesia35: 53-64.

-- . 1985. 'Opium in Java: a Sinister Friend'.Journalof AsianStudies44: 549-60.

Scott,J. M. I969. The WhitePoppy:a Historyof Opium.London: Heinemann.

SejarahKesehatanNasionalIndonesiavol. I. I978. Jakarta: Departemen Kesehatan.

Soerjono. I980. 'On Musso's Return.' Indonesia 29: 59-90.

Sundhaussen, Ulf. 1982. The Road to Power: IndonesianMilitary Politics i945-i966. Kuala

Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Sutter, John 0. 1959. Indonesianisasi: Politics in a ChangingEconomy, 940-i955, VolumeIl:

theIndonesian duringtheRevolution

Economy Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Southeast

Asia Program, I959.

Suryadinata, Leo. 1978. EminentIndonesianChinese:BiographicalSketches.Singapore:

Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Trocki, Carl A. I979. Princeof Pirates:the Temenggongs

and theDevelopment

of ohor and

Singapore1784-1885.Singapore: Singapore University Press.

Vanvugt, Ewald. I985. WettigOpium:350 Jaar NederlandseOpiumhandel in de Indische

Archipel.Haarlam: In de Knipscheer.

Alg. Sec. II Algemene Secretarie te Batavia, Tweede Zending (General Secretary

at Batavia, Second Despatch)

ARA Algemeen Rijksarchief (General State Archives)

AVMK Archiefvan het Voormalige Ministerie van Kolonien (Archives of the

Former Ministry of Colonies)

CMI Centrale Militaire Inlichtingendienst

ENI EncyclopaedievanNederlandsch-Indie

HKGS-NOI Hoofd Kwartier Generale, Staf, Nederlands Oost Indie

MvD/CAD Ministerie van Defensie, Centraal Archievendepot

This content downloaded from 130.56.64.29 on Fri, 27 Jun 2014 09:09:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

View publication stats

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The History of Revivals of Religion - William AllenDocumento83 pagineThe History of Revivals of Religion - William Allenkeithdr100% (1)

- CHC Policy Final EBRDocumento5 pagineCHC Policy Final EBRUgi CilikNessuna valutazione finora

- D05611924a PDFDocumento6 pagineD05611924a PDFUgi CilikNessuna valutazione finora

- Opium Dutch East IndiaDocumento8 pagineOpium Dutch East IndiavalentinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Indonesian Islamic Studies BibliographyDocumento20 pagineIndonesian Islamic Studies BibliographyUgi CilikNessuna valutazione finora

- Daftar Perguruan Tinggi Luar NegeriDocumento2 pagineDaftar Perguruan Tinggi Luar NegeriUgi CilikNessuna valutazione finora

- 47 PDFDocumento26 pagine47 PDFUgi CilikNessuna valutazione finora

- 47 PDFDocumento26 pagine47 PDFUgi CilikNessuna valutazione finora

- 47 PDFDocumento26 pagine47 PDFUgi CilikNessuna valutazione finora

- D05611924a PDFDocumento6 pagineD05611924a PDFUgi CilikNessuna valutazione finora

- D05611924a PDFDocumento6 pagineD05611924a PDFUgi CilikNessuna valutazione finora

- Slavery in Dutch ColoniesDocumento4 pagineSlavery in Dutch ColoniesUgi CilikNessuna valutazione finora

- ColombijnDocumento12 pagineColombijnUgi CilikNessuna valutazione finora

- SseathesesDocumento16 pagineSseathesesUgi CilikNessuna valutazione finora

- Lances Greased With Pork FatDocumento19 pagineLances Greased With Pork FatUgi CilikNessuna valutazione finora

- Hansen and Mowen Management Accounting CH 9Documento27 pagineHansen and Mowen Management Accounting CH 9Feby RahmawatiNessuna valutazione finora

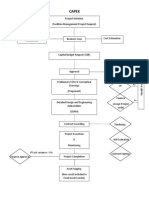

- CAPEXDocumento1 paginaCAPEXAmal KaNessuna valutazione finora

- Kaplan 1988 - One Cost System Isn't EnoughDocumento13 pagineKaplan 1988 - One Cost System Isn't EnoughSanjeev RanjanNessuna valutazione finora

- Third Outline Perspective Plan (Opp3) Chapter 3 - Macro Economic PerspectiveDocumento24 pagineThird Outline Perspective Plan (Opp3) Chapter 3 - Macro Economic PerspectiveChristy BrownNessuna valutazione finora

- Whiz Calculator Company Implements New Budgeting MethodDocumento14 pagineWhiz Calculator Company Implements New Budgeting MethodcimolenNessuna valutazione finora

- Lawsuit Found To Contain False Accusations Against DR Anthony TricoliDocumento3 pagineLawsuit Found To Contain False Accusations Against DR Anthony TricoliTrudyNessuna valutazione finora

- Note The Key Components of The Following Types of BudgetsDocumento2 pagineNote The Key Components of The Following Types of Budgetssajana kunwarNessuna valutazione finora

- CGA Ordinance 2001Documento5 pagineCGA Ordinance 2001Saeed Qadir BalochNessuna valutazione finora

- Simple Budget WorksheetDocumento4 pagineSimple Budget Worksheetapi-478639796Nessuna valutazione finora

- Economic Growth: Cameroon'SDocumento53 pagineEconomic Growth: Cameroon'SFabrice EwoloNessuna valutazione finora

- SALES BUDGET FORECASTING AND CONTROLDocumento30 pagineSALES BUDGET FORECASTING AND CONTROLArpan PalNessuna valutazione finora

- The Effect of The Global Financial Crisis and On Emerging and Developing EconomiesDocumento16 pagineThe Effect of The Global Financial Crisis and On Emerging and Developing EconomiesIPPRNessuna valutazione finora

- ECONOMICS (856Documento8 pagineECONOMICS (856Princess Soniya100% (1)

- Chapter 7. Supplies or Property: 356c of The LGC)Documento11 pagineChapter 7. Supplies or Property: 356c of The LGC)JeykeiPanganibanNessuna valutazione finora

- Effects of Top Managers' Military Experience On Technological Innovation in The Transition Economies of ChinaDocumento9 pagineEffects of Top Managers' Military Experience On Technological Innovation in The Transition Economies of ChinadoanthangNessuna valutazione finora

- Strategy and The Master BugdetDocumento38 pagineStrategy and The Master BugdetPhearl Anjeyllie PilotonNessuna valutazione finora

- MA2 Syllabus and Study Guide 2020-21 FINAL V2Documento14 pagineMA2 Syllabus and Study Guide 2020-21 FINAL V2Mokoena RalesupiNessuna valutazione finora

- Pmo Prince2 Building Blocks 110601 v2 0Documento49 paginePmo Prince2 Building Blocks 110601 v2 0Rehan TufailNessuna valutazione finora

- Arfan Fadillah (Pandangan Terkait Fungsi DPR)Documento4 pagineArfan Fadillah (Pandangan Terkait Fungsi DPR)Arfan FadillahNessuna valutazione finora

- Dungeon Master - Kingdom BuildingDocumento2 pagineDungeon Master - Kingdom BuildingJustin MorrisonNessuna valutazione finora

- Economics AQA As Unit 2 Workbook AnswersDocumento20 pagineEconomics AQA As Unit 2 Workbook AnswersFegsdf Sdasdf0% (1)

- PESS and PCER Report PDFDocumento29 paginePESS and PCER Report PDFEm Calvento MacaraegNessuna valutazione finora

- Pork BarrelDocumento2 paginePork BarrelJunjun16 JayzonNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Goal SettingDocumento9 pagineFinancial Goal SettingBablu ChauhanNessuna valutazione finora

- 08 Handout 1Documento7 pagine08 Handout 1Katelyn SungcangNessuna valutazione finora

- Monetary and Fiscal PolicyDocumento33 pagineMonetary and Fiscal Policyjuhi jainNessuna valutazione finora

- CA For Bank Exams Vol 1Documento167 pagineCA For Bank Exams Vol 1VenkatesanSelvarajanNessuna valutazione finora

- Analyzing Financial Performance of Public CompaniesDocumento4 pagineAnalyzing Financial Performance of Public CompaniesAlya IbrahimNessuna valutazione finora

- The City of Calgary 2020 Annual ReportDocumento104 pagineThe City of Calgary 2020 Annual ReportAdam ToyNessuna valutazione finora

- Creating An Investment Policy StatementDocumento15 pagineCreating An Investment Policy StatementDavid Lim100% (1)