Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Frenk J (2014) From Sovereignty To Solidarity - Concept of Global Health On Interdependence

Caricato da

Μιχάλης ΤερζάκηςTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Frenk J (2014) From Sovereignty To Solidarity - Concept of Global Health On Interdependence

Caricato da

Μιχάλης ΤερζάκηςCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Viewpoint

From sovereignty to solidarity: a renewed concept of global

health for an era of complex interdependence

Julio Frenk, Octavio Gómez-Dantés, Suerie Moon

Lancet 2014; 383: 94–97 The moment is ripe to revisit the idea of global health. indigenous populations of developed countries. Sup-

Harvard School of Public Despite tens of billions of dollars spent over the past porters of this original view regarded international needs

Health, Boston, MA, USA decade under the auspices of global health,1 a consensus as alien and peripheral, and very frequently as threats.

(Prof J Frenk PhD, S Moon PhD);

definition for this term remains elusive.2–5 Yet the way in Consistent with these ideas, international activities were

and National Institute of Public

Health, Cuernavaca, Mexico which we understand global health critically shapes not identified as aid and defence, and delivered through uni-

(O Gómez-Dantés MD) only which and whose problems we tackle, but also the lateral perspectives.

Correspondence to: way in which we raise and allocate funds, communicate The international health agenda was also affected by the

Prof Julio Frenk, Office of the with the public and policy makers, educate students, and idea that most health needs could be fully addressed with

Dean, Kresge 1005, Harvard

design the global institutions that govern our collective technology.10 This notion is still prevalent nowadays among

School of Public Health,

677 Huntington Avenue, Boston, efforts to protect and promote public health worldwide. various global health initiatives.11,12 The temptation to pin

MA 02115, USA The importance of advancing a coherent idea of global all hope on the latest technology is every bit as powerful as

deansoff@hsph.harvard.edu health has become clear in recent debates about the it was in the near past.13 This reductionist perspective

post-2015 development agenda. Health was central to contrasts with the growing realisation that most global

four of the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs; health problems have strong behavioural, cultural, social,

on hunger, child mortality, maternal health, and HIV/ political, and economic determinants that demand com-

AIDS and malaria) and directly linked as an outcome or prehensive—not only technical—approaches.

determinant to the four others (on primary education, International health also placed excessive emphasis on

gender equality and empowerment, environmental sus- vertical programmes devoted to control specific diseases

tainability, and global partnership). However, health and paid little attention to health systems as a whole,

advocates are concerned that health will not feature with well documented consequences.12 This tendency has

centrally in the post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals yet to be fully replaced by a more comprehensive diagonal

(SDGs), having had its moment in the spotlight and perspective that would use explicit intervention priorities

succumbing to competition from other issues demanding to drive improvements into the health system.14

attention, such as climate change or food security. But a International health cooperation has traditionally fallen

broader conceptualisation of global health makes clear under the rubric of foreign aid—support for polio eradi-

that health and sustainable development are inseparable. cation and treatment of HIV/AIDS are prominent

As recognised in the Rio+20 Declaration on the Future examples. But the very concept of aid conveys an

We Want, health “is a precondition for and an outcome asymmetric image in which problems and risks flow

and indicator of” sustainable development.6 from south to north, whereas resources and solutions

How should global health be understood in an era move in the opposite direction. This view fails to capture

marked by the rising burden of non-communicable the reality of health interdependence. It also fails to take

diseases (NCDs), climate change and other environ- into account the major shifts taking place in the global

mental crises, integrated chains of production and con- distribution of resources, influence, capabilities, and

sumption, a power shift towards emerging economies, needs as emerging economies continue their expansion.

intensified migration, and instant information trans- A sort of linguistic modernisation has revitalised the

mission? As we explain in this Viewpoint, global health traditional contents attributed to international health

should be reconceptualised as the health of the global through the use and dissemination of the notion of global

population, with a focus on the dense relationships of health. In the media, in lay and scientific literature, and in

interdependence across nations and sectors that have major initiatives, global health is still identified with

arisen with globalisation.7 Doing so will help to ensure problems supposedly characteristic of developing coun-

that health is duly protected and promoted, not only in tries, and global cooperation in health with a sort of

the post-2015 development agenda but also in the many paternalistic philanthropy that is armed with the tech-

other global governance processes—such as trade, invest- nological developments of developed countries. It is again

ment, environment, and security—that can profoundly the idea of the poor, ignorant, passive, and traditional

affect health.8 societies in need of the charity and technology of the rich

Since it was coined, around the creation of the Inter- that prevails in the use of this term. Paradoxically, this use

national Health Commission in 1913 by the Rockefeller of the notion of global health fails itself to capture the

Foundation,5 the term international health was identified essence of globalisation. In a real sense, we need to

with the control of epidemics across borders and with the globalise the concept of global health.

health needs of poor countries.9 Various textbooks To this end, it is necessary to move beyond reductionist

and training programmes also included the health of definitions and to reconceptualise global health to reflect

94 www.thelancet.com Vol 383 January 4, 2014

Viewpoint

two key notions. First, global health should not be viewed arising directly from globalisation. Irrespective of the type

as foreign health, but rather as the health of the global of resulting disease, global health risks spread through

population. Second, global health should be understood common processes created to support production, com-

not as a manifestation of dependence, but rather as munication, trade, and travel worldwide. These risks do

the product of health interdependence, a process that not necessarily move from developing to developed

has arisen in parallel with economic and geopolitical countries. For example, an often overlooked example of

interdependence.15 the transfer of health risks is the establishment of

The core idea behind the notion of health interdepen- polluting factories in developing nations, transplanted

dence is that no single stakeholder—not even the most from developed countries to take advantage of weaker

powerful government or corporation—is singlehandedly regulatory environments. Indeed, all countries, irrespec-

able to address all the health threats that affect it. Many tive of their location, wealth, history, or culture, are

determinants of health have globalised, such as the exposed to common health threats associated with global-

dissemination of patterns of work, lifestyles, diets, and isation. At the same time, the increased interdependence

other aspects of consumption that are conducive to produced by globalisation can generate new benefits and

diseases once thought to affect only rich societies— opportunities; every country can benefit from ideas,

diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer—now affect- knowledge, goods, regulatory approaches, and skills

ing many of the world’s poorer citizens in equal or originating elsewhere.18 Although the links between

greater measure. globalisation and health are complex,19–21 the transfer of

Although communicable diseases such as pandemic health risks and opportunities can be organised into six

influenza, malaria, or HIV/AIDS have attracted the broad categories: cross-border movement of elements of

greatest amount of funding, political attention, and the natural environment; people; production of goods and

institutional innovation,1 what were once regarded as services (eg, global value chains in manufacturing); con-

problems only of poor countries, such as many common sumption of goods and services (eg, food, tobacco, nar-

infections, malnutrition, and maternal deaths, are no cotics, health care); information, knowledge, and culture;

longer the only problems of such countries, who also carry and rules (table 1).22

the heaviest burden of many NCDs, mental disorders, and These six types of flows underscore the conclusion that

injuries. With the important exception of sub-Saharan no country—whether rich, poor, or middle income—can

Africa, in health terms developed and developing be isolated from the risks that emerge elsewhere. Such

countries have become more alike than different.16 NCDs interconnections are not necessarily new. But the

have attracted increased political attention, as their intensification of cross-border trade, travel, and com-

growing burden adds to and sometimes outweighs that of munication that are the hallmarks of globalisation have

communicable diseases in many poor societies.17 strengthened them and, in many cases, have created

Public health’s traditional binary classification of situations not merely of interconnection, but also of

communicable and non-communicable diseases fails to interdependence. Indeed, perhaps the two most striking

capture an additional layer of determination, which features of global health today are interconnectedness—

generates a novel category of health challenges—those both across countries and across sectors—in the causes

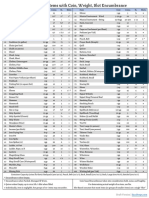

Examples of threats Examples of opportunities

Elements of the natural environment Environmental threats (eg, climate change, air and water Improved access to natural resources (eg, water)

pollution); spread of pathogens (eg, animal-borne

illnesses such as avian influenza)

People Spread of pathogens (eg, human-to-human Spread of knowledge and skills through workforce

transmission) movement

Production of goods and services Transplantation of harmful practices (eg, Economic growth and technology transfer

high-polluting factories to countries with weaker

regulatory systems); changing labour conditions

enabling adoption of sedentary lifestyles that

contribute to metabolic disorders

Consumption of goods and services Spread of harmful products (eg, tobacco); global trade Spread of useful medical technologies; adoption of

in unhealthy foods health-enhancing goods and services

Information, knowledge, and culture Inappropriate use of technologies (eg, leading to Spread of health-related knowledge and practices that

antimicrobial resistance) enhance health and wellbeing, such as family planning;

cross-fertilisation and access to new knowledge, whether

traditional or modern

Rules Transnational investment treaties restricting national Health-focused transnational rules, such as the WHO

regulatory policies; transnational intellectual property Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, expanding

rules increasing drug prices national policy space for health protection

Table 1: Cross-border flows that generate threats and opportunities of globalisation for health

www.thelancet.com Vol 383 January 4, 2014 95

Viewpoint

and effects of health threats, and interdependence in our states to do so. The challenge is that in a world of

capacity to respond to them effectively. sovereign states, there is no hierarchical authority or

It is important to distinguish between interconnection world government to fill in the gaps. Rather, there is only

and interdependence: interconnection describes the a relatively weak system of multilateral institutions built

nature of health threats and effects, whereas inter- on the shaky foundations of the consent of sovereign

dependence refers to the distribution of power, respon- states. Yet, the triple burden of disease can only be

sibility, and capacity to respond. For the very powerful, addressed through international collective action, which

such as governments of large wealthy countries, some must perform four major functions: to provide health-

health threats may be interconnected across borders but related public goods, such as research, standards, and

do not automatically imply interdependence, since they guidelines; to manage cross-national externalities

can largely manage these specific threats alone.23 However, affecting health through epidemiological surveillance,

for many others, particularly smaller, less wealthy coun- information sharing, and coordination; to mobilise

tries, or communities that live in closer proximity to global solidarity for populations facing acute or chronic

neighbouring countries, interdependence is a defining deprivation and disasters, whether natural or man-

feature of the domestic health landscape. Examples of made; and to exercise stewardship of the global health

health challenges linked to interdependence include system by convening stakeholders to reach consensus

regulation of the quality of imported food, medicines, on key issues, setting priorities, negotiating rules,

manufactured goods, and inputs; getting timely access to facilitating mutual accountability, and advocating for

information about the global spread of infectious diseases; health in other policy-making arenas.7

procurement of sufficient vaccine and drug supplies in a Fulfilment of these functions at the transnational

pandemic; and ensuring a sufficient corps of well-trained level will, in most cases, require building more robust

health personnel. global institutions for pooling risks, resources, and

Additionally, these challenges are interconnected across responsibilities among sovereign states—and in many

sectors—ie, their causes and the management of their cases, also non-state actors. Such institutions must

effects do not sit neatly within the traditional boundaries deepen cooperation to make it more predictable and

of the health sector or within the sole control of health reliable for all countries, even if some states might face

officials. Rather, an intricate web of governmental and short-term costs to build more politically sustainable

non-governmental players (eg, private firms, civil society global institutions in the long term. For example, states

organisations [CSOs], the media, and academic institu- could face immediate economic or political costs by

tions) all exercise some measure of influence over these swiftly reporting outbreaks of communicable disease to

health threats and the collective responses to them. WHO, as they are required to do by the International

Situations of complex interdependence frequently result, Health Regulations (IHR). Yet when states do so, provided

with many players working across different scales and that the response of other states is measured and

sectors ultimately shaping health outcomes. reasonable, it strengthens the global regime embodied in

In short, global health challenges are not only the the IHR and can improve health security for all.

diseases of the world’s poorest communities, but rather But generation of the political will within states to share

comprise all components of the triple burden of disease: their sovereignty in this manner will require a far more

first, the unfinished agenda of infections, malnutrition, fundamental transformation in the long term—the

and reproductive health problems; second, the emerging gradual construction of a global society. The idea of a

challenges represented by NCDs, mental disorders, and global society is based on the principles of human rights

injuries; and third, the health risks directly associated and the logic of health interdependence. It implies that

with globalisation. Global health challenges encompass individuals and the various organisations that they form

all issues that extend beyond the capacity of any one (whether governmental agencies, CSOs, firms, foun-

country to address, and often require concerted responses dations, or other stakeholders) accept to share the risks,

from governments and non-state stakeholders. rights, and duties related to protection and promotion of

Traditionally, the nation state has been responsible for the health of every member of this society. Although the

the protection of the health of its population. But notion of a global society might seem somewhat idealistic,

increased interdependence has eroded the capacity of it is partly based on the observation of a growing density

of social interactions and the spread of ideas and norms

Development aid International cooperation Global solidarity across borders, which raise new possibilities for develop-

Relationship Dependence Independence Interdependence ing a sense of solidarity between individuals and societies.

Actors Donors and recipients Independent member states Members of global society By setting global targets to improve maternal and child

Motivation Charity; self-interest Mutual benefit Shared responsibility health and combat hunger, HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other

Main instrument Discretionary allocations Pooled resources Shared resources based on major diseases, the MDGs arguably embodied the aspira-

universal rights and duties tions of a nascent global society for a common minimum

standard of health to which all people should be entitled

Table 2: Alternative framings of international transfers for health

as an essential human right.

96 www.thelancet.com Vol 383 January 4, 2014

Viewpoint

In the absence of a global government—not only now Acknowledgments

but for the foreseeable future—the construction of a global This Viewpoint has benefited from previous discussions with

Sue J Goldie and Jaime Sepúlveda, and comments on an earlier version

society emerges as a feasible alternative to harness of the manuscript from Tobias Rees.

interdependence in a world polity where sovereign nation

References

states coexist with expansive social networks transcending 1 Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Financing global health

national boundaries. In a world marked not only by deep 2012: the end of the golden age? Seattle: Institute for Health Metrics

inequities but also by the acceptance of a set of universal and Evaluation, 2012.

2 Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, et al, for the Consortium of

human rights, global solidarity becomes the unifying force Universities for Global Health Executive Board. Towards a common

to build a global society that could redress those inequities definition of global health. Lancet 2009; 373: 1993–95.

and assure the realisation of those rights. We use the term 3 Fried LP, Bentley ME, Buekens P, et al. Global health is public

health. Lancet 2010; 375: 535–37.

solidarity based on classic sociological theory, rather than

4 McInnes C, Lee K. Global health and international relations.

any particular political ideology, to refer to situations of Cambridge: Polity, 2012.

interdependence created by the complex division of roles 5 Brown TM, Cueto M, Fee E. The World Health Organization and

characteristic of modern societies.24 (In fact, the term has the transition from “international” to “global” public health.

Am J Public Health 2006; 96: 62–72.

been used by groups all along the political spectrum.) 6 Rio+20 UN Conference on Sustainable Development. The future we

The three different framings of global transfers for want, 2012. http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/futurewewant.

health—development aid, international cooperation, html (accessed July 15, 2013).

7 Frenk J, Moon S. Governance challenges in global health.

and global solidarity—each imply a different set of N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 936–42.

relationships, types of stakeholders, motivations, and 8 Ottersen OP, Frenk J, Horton R. The Lancet–University of Oslo

instruments (table 2). Although there is not necessarily a Commission on Global Governance for Health, in collaboration

linear progression from aid to cooperation to solidarity with the Harvard Global Health Institute. Lancet 2011; 378: 1612–13.

9 Godue C. International health and schools of public health in the

(in fact, nowadays all three framings operate simul- United States. In: Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), ed.

taneously), we argue that the term solidarity not only International health: a North-South debate. Washington, DC:

offers a more symmetrical expression of mutual respect Pan American Health Organization, 1992: 113–26.

10 Gómez-Dantés O. Health. In: Simmons PJ, De Jonge-Oudraat C,

between members of a society, but also best corresponds eds. Managing global issues. Lessons learned. Washington, DC:

to the underlying conditions of interdependence in an Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2001: 392–423.

unequal world. 11 Birn A. Gates’s grandest challenge: transcending technology as

public health ideology. Lancet 2005; 366: 514–19.

The idea of a global society should not be construed as a

12 World Health Organization Maximizing Positive Synergies

utopian world free of conflict. Rather, as in most national Collaborative Group. An assessment of interactions between global

societies, one would expect a global society to be charac- health initiatives and country health systems. Lancet 2009;

373: 2137–69.

terised by ongoing political conflict and competing views.

13 Rodin J. Navigating the global American South: global health and

What the notion of a global society does imply is that regional solutions. Plenary address presented at the University of

underpinning such conflicts would be a widely shared North Carolina Center for Global Initiatives; April 19, 2007.

understanding of health interdependence and an accept- 14 Sepúlveda J. Foreword. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham A,

et al, eds. Disease control priorities in developing countries,

ance of some responsibility for the health of others as 2nd edn. Washington, DC: Oxford University Press, 2006: xiii–xv.

members of the same society—in other words, a shared 15 Chen L, Bell D, Bates L. World health and institutional change.

commitment to realisation of health as a human right In: Pocantico Retreat. Enhancing the performance of international

health institutions. Cambridge, MA: The Rockefeller Foundation,

based on a recognition of our common humanity. Social Science Research Council, Harvard School of Public Health,

A clearer understanding of the fundamentally inter- 1996: 9–21.

connected nature of the health challenges faced by the 16 Bloom BR. Public health in transition. Sci Am 2005; 293: 92–99.

global community requires moving beyond the narrow 17 Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years

(DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010:

view of global health as the problems of the world’s poorest a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010.

societies, to global health as the health of an interdependent Lancet 2012; 380: 2197–223.

global population. Protection and promotion of the health 18 Keohane RO, Nye JS. Interdependence in world politics. In:

Crane GT, Amawi A, eds. The theoretical evolution of international

of a global society is one of the most central, yet daunting political economy: a reader. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

challenges of our time. Rethinking the term global health 19 Huynen M, Martens P, Hilderink H. The health impacts of

is a necessary first step towards its achievement. globalisation: a conceptual framework. Global Health 2005; 1: 14.

20 Labonte R, Schrecker T. Globalization and social determinants of

Contributors health: introduction and methodological background (part 1 of 3).

JF gave the original idea for the paper and contributed to its overall Global Health 2007; 3: 5.

structure and concepts. He contributed to the writing and editing of 21 Lee K, Sridhar D, Patel M. Bridging the divide: global governance of

subsequent drafts, and the conclusions. OG-D contributed to the overall trade and health. Lancet 2009; 373: 416–22.

structure of the paper and the development of its concepts. He also 22 Frenk J, Sepúlveda J, Gómez-Dantés O, McGuiness MJ, Knaul F.

participated in the writing and editing of the various drafts and The future of world health: the new world order and international

conclusions. SM revised the content and structure of the manuscript. She health. BMJ 1997; 314: 1404–07.

also contributed to the addition or refinement of concepts, arguments, 23 Fidler D. Rise and fall of health as a foreign policy issue.

and conclusions. All authors have approved the final version of the paper. Global Health Gov 2011; 4: 1–12.

Conflicts of interest 24 Durkheim E. The divison of labor in society. Glencoe: Free Press,

1964.

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

www.thelancet.com Vol 383 January 4, 2014 97

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1091)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Crypts of Kelemvor 5eDocumento15 pagineCrypts of Kelemvor 5eΜιχάλης ΤερζάκηςNessuna valutazione finora

- Reference BookletDocumento35 pagineReference BookletΜιχάλης Τερζάκης57% (7)

- Exc Cat #17 320 CuDocumento2 pagineExc Cat #17 320 CuWashington Santamaria100% (4)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Shop Manual PC78MR-6-SEBM030601 PDFDocumento592 pagineShop Manual PC78MR-6-SEBM030601 PDFBudi Waskito95% (20)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Old-School Essentials Adventure Anthology 1 v0-4Documento44 pagineOld-School Essentials Adventure Anthology 1 v0-4Μιχάλης Τερζάκης20% (5)

- Case 4 Sakhalin 1 ProjectDocumento29 pagineCase 4 Sakhalin 1 ProjectashmitNessuna valutazione finora

- ITIL Cobit MappingDocumento16 pagineITIL Cobit Mappingapi-383689667% (3)

- Frangible Roof To Shell JointDocumento1 paginaFrangible Roof To Shell JointSAGARNessuna valutazione finora

- Stonehell Dungeon, Lost Level (LL)Documento8 pagineStonehell Dungeon, Lost Level (LL)Μιχάλης ΤερζάκηςNessuna valutazione finora

- The Isle of Forgotten Gods (Basic, BX)Documento38 pagineThe Isle of Forgotten Gods (Basic, BX)Μιχάλης Τερζάκης100% (1)

- Recruitment (Robotic) Process Automation (RPA)Documento6 pagineRecruitment (Robotic) Process Automation (RPA)Anuja BhakuniNessuna valutazione finora

- Dolmenwood Hex Crawl ProcedureDocumento2 pagineDolmenwood Hex Crawl ProcedureΜιχάλης Τερζάκης100% (2)

- Old-School Essentials Adventure Anthology 2 v0-3Documento38 pagineOld-School Essentials Adventure Anthology 2 v0-3Μιχάλης Τερζάκης0% (2)

- OSE The Pelietic ChurchDocumento3 pagineOSE The Pelietic ChurchΜιχάλης ΤερζάκηςNessuna valutazione finora

- Tangled (Pages) (OSE)Documento24 pagineTangled (Pages) (OSE)Μιχάλης Τερζάκης50% (8)

- Dolmenwood House Rules (NGP) (Basic, BX)Documento1 paginaDolmenwood House Rules (NGP) (Basic, BX)Μιχάλης Τερζάκης0% (1)

- Key Performance IndicatorsDocumento72 pagineKey Performance Indicatorstamhieu75% (4)

- ENIRAM - Guide To Dynamic Trim Optimization 280611 PDFDocumento14 pagineENIRAM - Guide To Dynamic Trim Optimization 280611 PDFPhineas MagellanNessuna valutazione finora

- OSE Random Gear - FUNNEL GEARDocumento1 paginaOSE Random Gear - FUNNEL GEARΜιχάλης ΤερζάκηςNessuna valutazione finora

- Illmire Pre-Gen CharDocumento7 pagineIllmire Pre-Gen CharΜιχάλης ΤερζάκηςNessuna valutazione finora

- GE Lighting Systems Indoor Lighting Designers Guide 1970Documento56 pagineGE Lighting Systems Indoor Lighting Designers Guide 1970Alan Masters100% (1)

- The Dolmenwood CalendarDocumento22 pagineThe Dolmenwood CalendarΜιχάλης Τερζάκης100% (1)

- T Series TorqueDocumento8 pagineT Series TorqueBrian OctavianusNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Epidimiology - HistoryDocumento7 pagineSocial Epidimiology - HistoryΜιχάλης ΤερζάκηςNessuna valutazione finora

- Item Cost Coins Lb. Slots Item Cost Coins Lb. Slots: Draft VersionDocumento1 paginaItem Cost Coins Lb. Slots Item Cost Coins Lb. Slots: Draft VersionΜιχάλης ΤερζάκηςNessuna valutazione finora

- Gauld Et Al WHR 2008 PHC Policy How Wide Is The Gap Between Agenta and Implementation 12 High IncomeDocumento21 pagineGauld Et Al WHR 2008 PHC Policy How Wide Is The Gap Between Agenta and Implementation 12 High IncomeΜιχάλης ΤερζάκηςNessuna valutazione finora

- Origins of PHC and SPHCDocumento11 pagineOrigins of PHC and SPHCΜιχάλης ΤερζάκηςNessuna valutazione finora

- Difference SPHC Vs CPHCDocumento9 pagineDifference SPHC Vs CPHCΜιχάλης ΤερζάκηςNessuna valutazione finora

- Hikvision Fever Screening Thermal CameraDocumento1 paginaHikvision Fever Screening Thermal CameraΜιχάλης ΤερζάκηςNessuna valutazione finora

- DRA12 - The Barber of Silverymoon PDFDocumento13 pagineDRA12 - The Barber of Silverymoon PDFlordejulioNessuna valutazione finora

- REC-551-POC-Quiz - 2Documento1 paginaREC-551-POC-Quiz - 2Jinendra JainNessuna valutazione finora

- The Masterbuilder - July 2013 - Concrete SpecialDocumento286 pagineThe Masterbuilder - July 2013 - Concrete SpecialChaitanya Raj GoyalNessuna valutazione finora

- Woolridge - Reasnoning About Rational AgentsDocumento232 pagineWoolridge - Reasnoning About Rational AgentsAlejandro Vázquez del MercadoNessuna valutazione finora

- CNC Macine Dimesions-ModelDocumento1 paginaCNC Macine Dimesions-ModelNaveen PrabhuNessuna valutazione finora

- DUROFLEX2020 LimpiadorDocumento8 pagineDUROFLEX2020 LimpiadorSolid works ArgentinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Content - EJ 2014 Galvanised GratesDocumento32 pagineContent - EJ 2014 Galvanised GratesFilip StojkovskiNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Web TechnologiesDocumento8 pagineIntroduction To Web TechnologiesManeela SiriNessuna valutazione finora

- Passenger Terminal Building ProposalDocumento6 paginePassenger Terminal Building ProposalHimawan Aryo DewantoroNessuna valutazione finora

- Lab 2 WorksheetDocumento3 pagineLab 2 WorksheetPohuyistNessuna valutazione finora

- Accreditation Grading Metrics - Skills Ecosystem Guidelines10 - 04Documento8 pagineAccreditation Grading Metrics - Skills Ecosystem Guidelines10 - 04Jagdish RajanNessuna valutazione finora

- Brosur All New Innova MUVs 16393Documento7 pagineBrosur All New Innova MUVs 16393Roni SetyawanNessuna valutazione finora

- Skiold Trough Augers: SkioldgroupDocumento2 pagineSkiold Trough Augers: SkioldgroupLuis NunesNessuna valutazione finora

- 4.1 Introduction To Studying Two Factors: ESGC 6112: Lecture 4 Two-Factor Cross-Classification DesignsDocumento14 pagine4.1 Introduction To Studying Two Factors: ESGC 6112: Lecture 4 Two-Factor Cross-Classification DesignsragunatharaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Pengumuman Matakuliah Pilihan 2110 - KMGDocumento85 paginePengumuman Matakuliah Pilihan 2110 - KMGMartha Wulan TumangkengNessuna valutazione finora

- SR5 TOOL Equipment, Drones (Buyable), Compiled ListDocumento3 pagineSR5 TOOL Equipment, Drones (Buyable), Compiled ListBeki LokaNessuna valutazione finora

- Oil and DrillingDocumento3 pagineOil and DrillingAmri YogiNessuna valutazione finora

- Bomb Oil AisinDocumento38 pagineBomb Oil AisinMAURICIONessuna valutazione finora

- 12jun27 FC Perfect Stores Add Zing To HUL's Sales Growth - tcm114 289918 PDFDocumento1 pagina12jun27 FC Perfect Stores Add Zing To HUL's Sales Growth - tcm114 289918 PDFSantosh SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Guide To Creating and Editing Metadata in Arcgis For Publishing To The Msdis GeoportalDocumento24 pagineGuide To Creating and Editing Metadata in Arcgis For Publishing To The Msdis Geoportalvela.letaNessuna valutazione finora

- TCH Assignment Success Rate (%)Documento7 pagineTCH Assignment Success Rate (%)AbebeNessuna valutazione finora